1. Introduction

The issue of economic freedom has historically been a significant subject in international economic discussions. It is widely believed that economic freedom promotes the development of a robust banking system, which in turn supports long-term economic growth. Empirical studies often confirm this view, showing that economic freedom is positively associated with financial development and economic outcomes (

Carlsson & Lundström, 2002;

Dawson, 2003;

Karabegovic et al., 2003;

Piątek et al., 2013).

Baier et al. (

2012) argue that increasing economic freedom diminishes the probability of banking crises. Similarly,

Shehzad and De Haan (

2009) find that financial liberalization, often used as a proxy for greater economic freedom in financial markets, can contribute to lower systemic risk.

Despite these findings, the relationship between economic freedom and bank performance remains contested. Critics warn that liberalization and deregulation may, under certain conditions, undermine stability by encouraging excessive risk-taking and weakening supervisory oversight (

J. E. Stiglitz, 2009). Past financial crises have been linked to rapid liberalization (

Demirgüç-Kunt & Detragiache, 1998;

Kaminsky & Reinhart, 1999;

Soedarmono, 2011). Economic freedom can also intensify competition, exerting downward pressure on bank profitability (

Demirgüç-Kunt et al., 2003). Conversely, other studies report that liberalization enhances efficiency and performance (

Al-Gasaymeh, 2018;

Chortareas et al., 2013;

Ghosh, 2016;

Gropper et al., 2015;

Mavrakana & Psillaki, 2019;

Sufian & Habibullah, 2010a,

2010b). These conflicting results highlight that the effects of economic freedom are not uniform but depend on institutional and market contexts.

One of the most important contextual factors is bank capitalization. Capital buffers serve as shock absorbers, allowing banks to sustain operations and maintain confidence in times of market stress. Capital also improves long-term profitability and stability (

Athanasoglou et al., 2008;

Berger & Bouwman, 2013;

Chortareas et al., 2013;

De Jonghe, 2010;

Laeven & Levine, 2009). At the same time, robust regulatory frameworks are essential for guiding bank behavior.

Klomp and de Haan (

2014) stress that supervisory quality and capital regulation play a vital role in mitigating risks, particularly in emerging economies. Thus, sufficient capitalization is expected to perform two critical functions: safeguarding stability and enhancing performance (

Barth et al., 2004;

Santoso et al., 2021;

Yudaruddin, 2017).

Empirical evidence shows that developed economies, where institutions are strong and regulatory enforcement is consistent, tend to benefit more from economic freedom (

de Almeida et al., 2024;

Hung et al., 2024). Emerging markets, however, face weaker institutional capacity, uneven enforcement, and higher exposure to global shocks, which may limit the benefits of liberalization (

Bjørnskov, 2016;

Claessens & Yurtoglu, 2013). This divergence suggests that capitalization may play a moderating role in determining whether economic freedom strengthens or undermines banking outcomes.

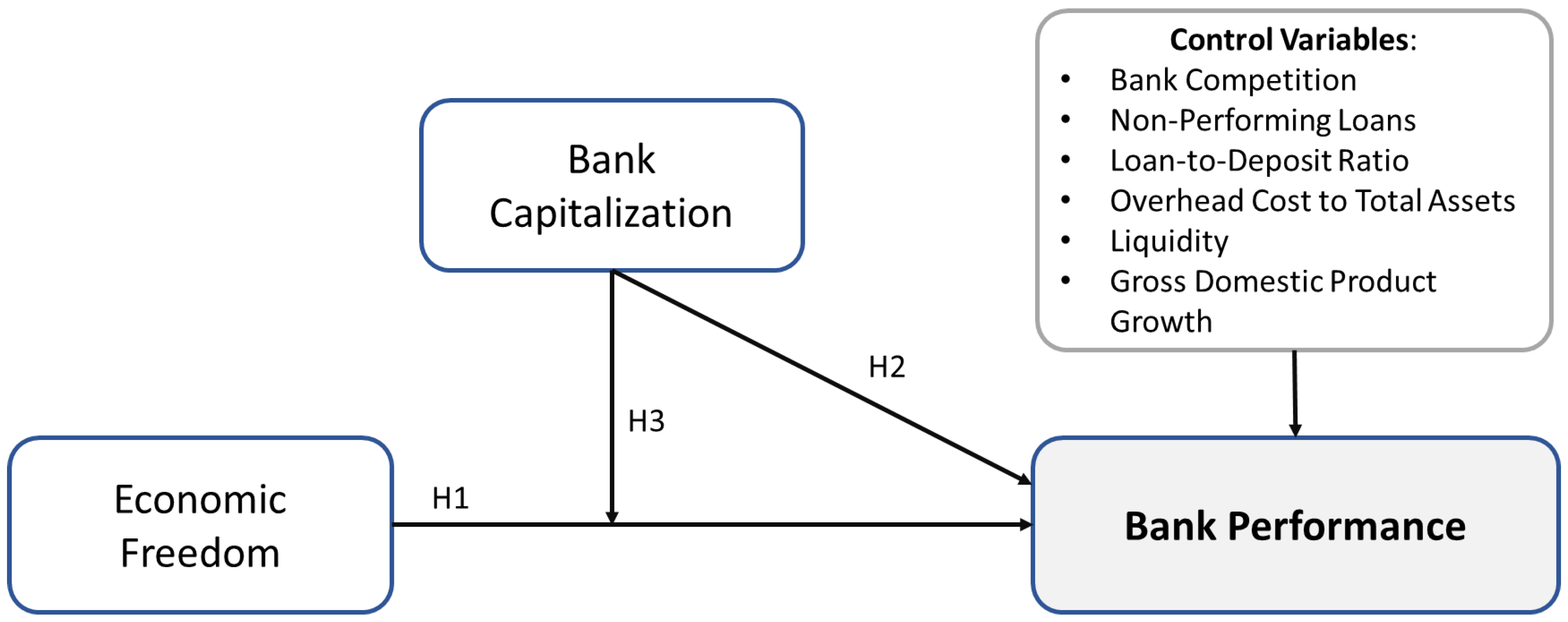

This study builds on these debates by examining the interaction between economic freedom, bank capitalization, and bank performance across both advanced and emerging economies. Using a panel dataset of 213 countries from 1993 to 2018, we provide one of the most comprehensive analyses to date. Our work extends

Demirgüç-Kunt et al. (

2003), who found that economic freedom tends to reduce banks’ net interest margins, by incorporating capitalization as a moderating factor and comparing different country contexts. In doing so, we address a gap in the literature, as prior studies have largely overlooked the combined role of economic freedom and capitalization on banking outcomes.

This paper makes three contributions. First, it provides large-scale evidence that distinguishes between advanced and emerging markets, showing how institutional differences shape the freedom–performance nexus. Second, it incorporates bank capitalization as a moderating factor, clarifying how capital buffers mitigate or amplify the effects of liberalization. Third, and most importantly, the novelty of this study lies in combining these perspectives: we not only use a comprehensive global dataset but also compare two different forms of capitalization (internal equity-to-assets ratio and regulatory capital adequacy ratio) to evaluate which type of capital is more effective in supporting resilience under liberalized conditions.

In line with these aims, this study seeks to answer three core questions: does economic freedom have a significant impact on bank performance, what is the role of bank capitalization in directly influencing performance, and how does capitalization moderate the relationship between economic freedom and bank performance across different institutional contexts? By addressing these questions, the study contributes both theoretically, by clarifying the conditions under which liberalization improves or undermines bank outcomes, and practically, by informing regulators and policymakers on the importance of strengthening capitalization in tandem with financial liberalization.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews the relevant theoretical and empirical literature.

Section 3 describes the data and methodology.

Section 4 presents the empirical results, followed by a separate discussion in

Section 5.

Section 6 concludes the study.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation

Descriptive statistics for every variable in both advanced and emerging market economies are shown in

Table 2. The average return on assets (ROA) is 1.37%, while the return on equity (ROE) averages 14.30%. When market classification is taken into account, advanced economies show lower average ROA (

M = 0.92%) and ROE (

M = 10.28%) than emerging markets (

M = 1.62% and

M = 16.53%, respectively). This suggests that banks operating in less developed financial systems are more profitable.

There is also a noticeable difference in the Economic Freedom (EF) index, with advanced markets having a much higher average score (M = 69.97) than emerging markets (M = 54.90). Interestingly, emerging markets have generally higher levels of bank capitalization as measured by the capital-to-assets ratio (CAPTA) and the regulatory capital adequacy ratio (CAR), suggesting that these areas have stronger capital buffers.

The Boone indicator (COMP), which measures market competition, shows that advanced economies are under more competitive pressure (M = −1.26) than emerging ones (M = −0.14). Key control variables like credit risk (non-performing loans, or NPL), liquidity (LIQ), and the overhead cost ratio (OVER) also show notable variations. The statistical significance of these differences across all variables is confirmed by independent samples t-tests.

Pearson correlation coefficients between the primary variables are shown in

Table 3. Given their shared function as profitability indicators, ROA and ROE have a strong correlation (

r = 0.6785,

p < 0.001). Both ROA and ROE have a negative correlation with EF, indicating that there may be a negative relationship between bank performance and economic liberalization. Furthermore, there is a strong positive correlation between CAPTA and CAR (

r = 0.7038,

p < 0.001), suggesting that the two capitalization measures are aligned. The inclusion of these variables in the regression models is validated by the fact that all correlation coefficients are below the traditional multicollinearity threshold (

r < 0.80).

4.2. Baseline Regression Results

The baseline regression results are shown in

Table 4. Columns (1) through (6) report dynamic panel estimates using ROA and ROE as dependent variables for the full sample, as well as for advanced and emerging markets separately. The findings show that Economic Freedom (EF) has a statistically significant and adverse impact on bank performance on both profitability metrics. In emerging markets, where the coefficients are larger in magnitude and more statistically significant, this effect is more noticeable.

The negative correlation suggests that greater economic freedom, which is typified by less regulation and more market openness, can reduce profit margins, especially in banking systems with weak structural foundations. These results are in line with earlier research that suggested liberalization reduces market power, tightens interest margins, and increases competition.

Furthermore, the idea that stronger capitalization improves performance in more developed banking systems is supported by the positive correlation between CAPTA and ROA in advanced markets (p < 0.01). In contrast, the Boone indicator (COMP) shows a strong and positive correlation with performance, especially in emerging markets where profitability seems to be supported by less fierce competition (i.e., higher COMP values).

4.3. Moderating Role of Bank Capitalization (CAPTA)

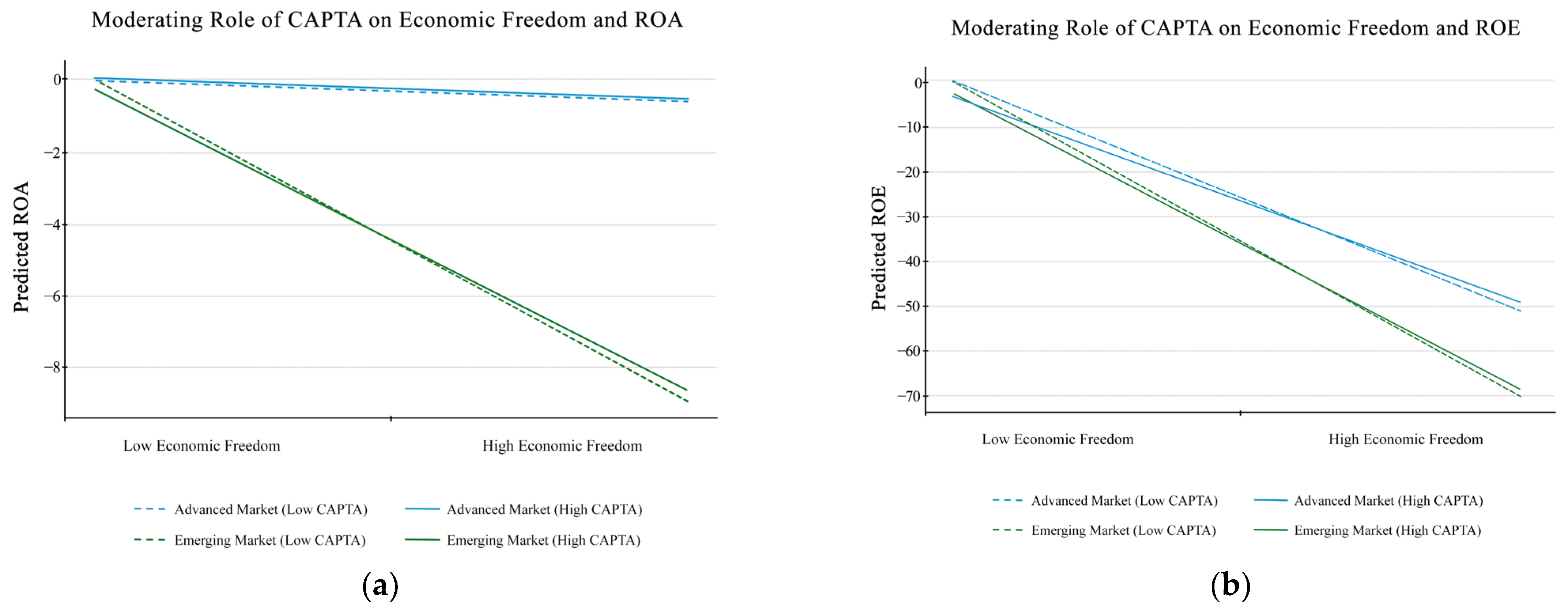

Figure 2 shows the expected values of return on equity (ROE) and return on assets (ROA) across increasing levels of economic freedom, demonstrating the moderating effect of bank capitalization (CAPTA) on the relationship between EF and bank performance. To provide a better understanding of the interaction effects seen in the regression analysis, each line represents various combinations of market type (emerging or advanced) and capitalization level (low or high).

The slope for advanced markets appears almost flat under both low and high capitalization, as seen in

Figure 2a, which shows ROA. This suggests that in more developed financial systems, economic freedom has a negligible impact on bank profitability. Conversely, when capitalization is low, emerging markets exhibit a more pronounced decline in ROA; at high capitalization, the slope becomes more moderate. This pattern suggests that banks in emerging economies are better able to handle the structural changes and competitive pressures brought about by greater economic freedom when they have stronger capital positions.

Figure 2b shows the relationship for ROE and demonstrates a stronger moderating effect. In advanced markets, ROE decreases significantly under low capitalization, but the negative trend is weakened—and nearly neutralized—when capitalization is high. A similar trend can be seen in emerging markets, where the negative effect of economic freedom on ROE is much lessened as capitalization rises. These patterns support the idea that banks with a lot of capital are more stable and can turn economic liberalization into better performance.

The visual trends shown in

Figure 2 come from the interaction models that were estimated in this study.

Appendix A,

Table A1 shows the full regression outputs, including coefficients and significance levels. This table gives the full statistical basis for these results.

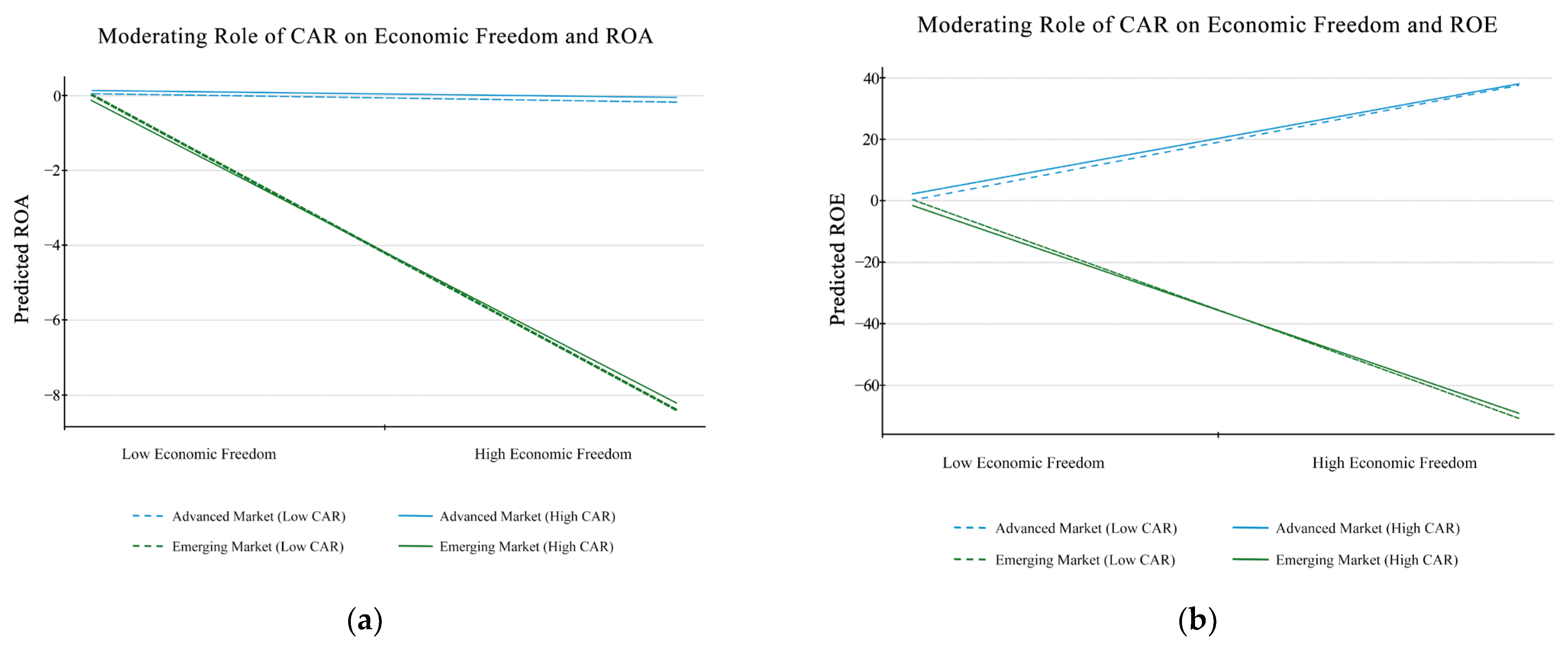

The analysis is further extended by investigating the moderating influence of regulatory capital, measured by the capital adequacy ratio (CAR), on the relationship between economic freedom and bank performance.

Figure 3 shows how this interaction looks. It shows the predicted values of ROA and ROE at different levels of economic freedom, broken down by market classification (advanced vs. emerging) and regulatory capital levels (low vs. high).

As shown in

Figure 3a, which displays ROA, advanced markets show a flat response to economic freedom regardless of CAR levels, indicating limited sensitivity to liberalization in more stable financial systems. In contrast, emerging markets exhibit a notably steeper decline in ROA under low CAR conditions, while this effect becomes considerably more moderate when CAR is high. This suggests that regulatory capital plays a buffering role in less mature financial markets, mitigating the adverse impact of economic freedom on profitability.

Figure 3b reinforces this conclusion through the lens of ROE. The negative slope in emerging markets with low CAR reflects a strong decline in bank performance as economic freedom increases. However, when CAR is high, this downward trend is substantially reduced, demonstrating the stabilizing effect of adequate capital reserves. In advanced markets, meanwhile, both low- and high-CAR scenarios produce relatively stable ROE values, consistent with expectations that mature regulatory frameworks already provide structural protections.

Overall, these findings highlight the role of regulatory capital in supporting bank resilience under liberal economic conditions, particularly in emerging markets. Although the moderating effect of CAR is less pronounced in advanced economies, it remains directionally consistent and underscores the importance of capital adequacy standards in mitigating systemic risk. Full regression results underlying these visualizations are presented in

Appendix A,

Table A2.

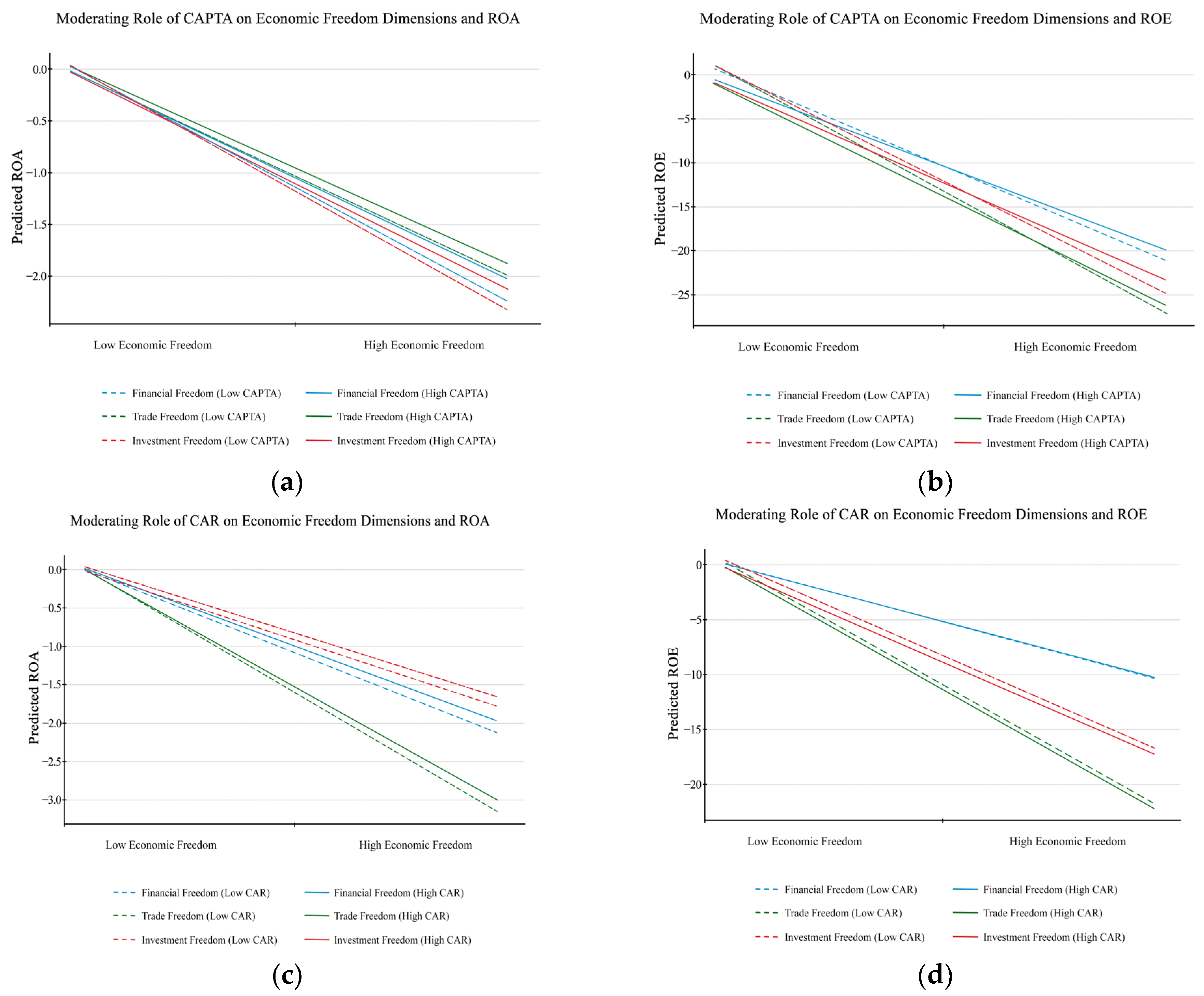

Figure 4 extends this analysis by concentrating on the interaction between bank capital (CAPTA and CAR) and specific dimensions of economic freedom—specifically, financial freedom (FIN), trade freedom (TRADE), and investment freedom (INVT)—in relation to bank performance (ROA and ROE). Each subplot shows how predicted performance changes when capitalization or regulatory capital is low or high.

Figure 4a shows that both FIN and INVT have significant interaction effects with CAPTA (

t = 2.03 and

t = 1.99, respectively;

p < 0.05). This means that higher bank capitalization lessens the negative effects of financial and investment liberalization on ROA. Under high-CAPTA conditions, the slopes are flatter, which means they are more resistant. On the other hand, TRADE does not show a significant interaction effect (

t = 0.43), and the lines stay almost parallel.

Figure 4b reveals that CAPTA significantly moderates the relationship between all three economic freedom dimensions and ROE. The interaction terms for FIN, TRADE, and INVT are statistically significant (

t > 2.00), and INVT has the strongest effect on the other two. These findings suggest that banks with greater capitalization are more resilient to competitive pressures and can capitalize on liberalized markets, particularly regarding equity performance.

Figure 4c,d, on the other hand, shows that regulatory capital (CAR) does not have a big effect on the link between economic freedom and either ROA or ROE. The interaction terms across FIN, TRADE, and INVT are not statistically significant (

t < 1.30), and the predicted trend lines for low and high CAR remain nearly parallel. This implies that CAR, at least in the observed context, plays a limited role in conditioning the impact of economic freedom on bank performance.

Together, these findings suggest that bank capitalization (CAPTA) serves as a more robust and consistent moderating factor than regulatory capital (CAR), especially in mitigating the negative effects of financial and investment liberalization. The complete statistical outputs supporting these results are available in

Appendix A,

Table A3.

4.4. Robustness Tests Using Lagged Variables

To ensure robustness of the baseline and interaction models, lagged specifications of EF, CAPTA, and CAR are employed.

Table 5 shows that the main findings persist when lagged variables are introduced, with EF remaining negatively significant and EF × CAPTA/EF × CAR maintaining their positive and significant effects on both ROA and ROE.

This temporal robustness supports the causal interpretation of the observed relationships. It implies that past levels of economic freedom and bank capitalization have a measurable influence on current bank performance, reinforcing the role of strategic capital planning in dynamic regulatory environments.

4.5. Alternative Performance Measure: Net Interest Margin

Table 6 introduces net interest margin (NIM) as a complementary indicator of banking performance, reflecting the efficiency of interest income generation rather than overall profitability. The results remain consistent with the baseline findings: economic freedom exerts a statistically significant and negative influence on NIM, while the interaction between economic freedom and capitalization (EF × CAPTA) is positively associated with NIM at conventional levels of significance. This suggests that greater economic liberalization tends to compress margins in lending and deposit markets, but stronger capitalization helps to offset this effect, supporting more stable intermediation efficiency under competitive pressures.

5. Discussion

The results indicate that economic freedom exerts a negative impact on bank performance, as measured by ROA and ROE, meaning Hypothesis 1 is not supported. This pattern emerges consistently across specifications and country groups. Our empirical evidence therefore suggests that, rather than enhancing efficiency, greater liberalization can undermine profitability. These findings align with

Socol and Iuga (

2025), who show that increases in financial freedom reduce banking performance due to stronger competition and market liberalization pressures, including competition from non-bank financial institutions such as hedge funds and private equity firms. We now cross-reference these observed patterns with interpretations in prior literature.

Earlier studies often reported positive effects of economic freedom on growth and efficiency (

Bergh & Karlsson, 2010;

Heckelman & Powell, 2010). However, much of that literature focused on advanced economies with robust supervisory institutions, where liberalization can promote discipline and innovation. By contrast, our evidence covering emerging and developing countries indicates that weaker supervisory capacity, higher vulnerability to capital inflows, and fragile institutional environments amplify risks (

Abdullah et al., 2018;

Masrizal et al., 2024;

Santiago et al., 2020). The destabilizing dynamics observed here are consistent with

D. J. Stiglitz (

2009), who argued that deregulation fosters excessive risk-taking and may encourage unethical practices such as misrepresentation of credit quality, predatory lending, or accounting manipulation (

Korinek & Kreamer, 2014). These mechanisms provide institutional and behavioral explanations for the negative outcomes observed in our results.

At the same time, our findings support a non-monotonic interpretation of liberalization outcomes. In advanced markets, stronger legal and regulatory frameworks, coupled with instruments like Basel III capital requirements, allow banks to absorb risks and benefit from openness (

Adam et al., 2023;

Claessens & Yurtoglu, 2013;

Gropper et al., 2015). In fragile systems, however, liberalization without adequate safeguards undermines stability, validating recent insights on the importance of macroprudential policies in conditioning the effects of capital flows and competition (

Hodula & Ngo, 2022;

Kuzman et al., 2022).

Cross-country differences in banking structures further explain the heterogeneity of outcomes. Advanced economies typically feature deeper capital markets, more diversified funding structures, stronger regulatory enforcement, and robust deposit insurance systems. Emerging markets, by contrast, remain more reliant on bank intermediation, often depend on foreign funding, and operate under weaker supervisory institutions (

Li, 2019;

Makler & Ness, 2002). Basel III implementation has also magnified these divides: large banks in advanced markets generally adapt well, whereas smaller banks in emerging economies often face efficiency losses from compliance burdens (

Gržeta et al., 2023). These structural contrasts mean that similar increases in economic freedom have very different consequences across market groups, amplifying the negative effects in fragile systems while fostering efficiency in mature ones.

Turning to capitalization, the equity-to-assets ratio (CAPTA) has a consistently positive impact on ROA, thereby supporting Hypothesis 2. This highlights the stabilizing role of internal capital buffers in absorbing shocks, consistent with

Athanasoglou et al. (

2008) and

Berger and Bouwman (

2013). The effect on ROE is weaker, reflecting diminishing returns to equity and the costs of overcapitalization (

Dao & Nguyen, 2020;

T. D. Q. Le & Ngo, 2020). By contrast, the capital adequacy ratio (CAR) shows weaker or negative links to profitability. Importantly, CAR functions as a nominant variable: very low levels heighten fragility, while excessively high levels constrain lending and reduce returns (

Athanasoglou et al., 2008;

Malovaná & Ehrenbergerová, 2022). This duality reflects broader macroprudential debates: while higher capital and liquidity standards can mitigate systemic risks (

Luu et al., 2024;

Walther, 2016), excessive conservatism may depress lending and slow growth. This trade-off reinforces CAR’s role in balancing profitability and stability.

The interaction effects strongly support Hypothesis 3. CAPTA consistently moderates the adverse impact of economic freedom, enabling banks to withstand volatility, reduce reliance on unstable funding, and maintain performance under liberalized conditions (

Al-Zoubi & Sha’ban, 2023;

Mehzabin et al., 2022;

Santoso et al., 2021). This moderating role is especially important in emerging markets, where weak institutions heighten vulnerability (

Saleh & Abu Afifa, 2020;

Trung, 2021). In advanced economies, reliance on capital buffers is less pronounced because external safeguards, such as deposit insurance, risk-based supervision, and predictable macroeconomic environments, already provide stability. This echoes resilience-focused research suggesting that robust internal capitalization complements formal regulatory frameworks in ensuring post-crisis recovery and long-run stability (

Greenwood et al., 2017;

Haile et al., 2025).

Disaggregating economic freedom into financial, trade, and investment dimensions further clarifies these dynamics. CAPTA significantly mitigates the negative effects of financial and investment freedom on profitability, particularly ROE, while its interaction with trade freedom is weaker. This indicates that liberalization of credit and capital flows is more destabilizing than trade openness unless supported by strong equity buffers (

Alraheb et al., 2019;

Giannetti, 2003). Macroprudential measures such as loan-to-value caps or dynamic provisioning are particularly relevant in this regard, as they offset the risks of financial and investment liberalization when equity buffers alone are insufficient (

Hodula & Ngo, 2022;

Kogler, 2020). By contrast, CAR shows weaker and inconsistent moderating effects: while higher CAR supports resilience in some emerging markets, its externally imposed nature appears less adaptive to market pressures compared with internal capitalization. This suggests that regulatory capital standards alone may lack the flexibility or strategic responsiveness needed in dynamic policy environments. These findings echo concerns raised by

Dao and Nguyen (

2020) and

T. D. Q. Le and Ngo (

2020), highlighting the potential disconnect between formal regulation and practical risk absorption capacity.

The control variables provide further insights into banking performance. Non-performing loans (NPLs) reduce profitability by lowering interest income and raising provisioning costs, which directly erodes capital and efficiency (

Athanasoglou et al., 2008;

Lafuente et al., 2019). Overhead costs also depress ROA and ROE, as higher operating expenses relative to income signal inefficiency in resource allocation (

Dietrich & Wanzenried, 2011;

Tan, 2016).

GDP growth, somewhat counterintuitively, is negatively associated with profitability. Expansionary phases often intensify competition, compress lending margins, and encourage riskier credit expansion, thereby lowering returns (

Shehzad & De Haan, 2009;

Tan & Floros, 2012). Similarly, high loan-to-deposit ratios (LDR) reduce efficiency by exposing banks to liquidity shortages and funding risks, especially in systems with underdeveloped capital markets (

Ghosh, 2016).

Liquidity (LIQ), by contrast, strengthens profitability by enhancing shock absorption and depositor confidence, which stabilizes earnings even during downturns (

Alkhazali et al., 2024;

Athanasoglou et al., 2008). Competition (COMP), measured by the Boone index, shows mixed results: while intense competition erodes margins, it may also drive efficiency and innovation, explaining the dual outcomes observed (

Ariss, 2010;

Boone, 2008).

Finally, the profitability gap between advanced and emerging markets is consistent with structural features of their banking systems. Advanced economies report lower ROA and ROE due to narrower spreads, stronger competition, and the presence of non-bank financial alternatives, while emerging economies sustain higher profitability through weaker competition, underdeveloped capital markets, and higher risk premiums (

Erdas & Ezanoglu, 2022). These findings confirm that institutional and structural differences are decisive in shaping how liberalization and capitalization jointly affect performance.

Taken together, the findings reinforce that the negative effects of economic freedom in this study are not a contradiction of prior literature but rather a reflection of institutional variation. By embedding the results within the broader debates on Basel III, macroprudential regulation, and banking resilience, the analysis highlights that bank capitalization, particularly internal buffers, emerges as the key safeguard conditioning whether liberalization erodes or enhances profitability and stability.

6. Conclusions

This study investigates the relationship between economic freedom, bank capitalization, and banking performance across a global sample of countries. By examining the moderating role of capital in the economic freedom–performance nexus, the analysis provides new insights into how liberalization and internal buffers interact in diverse institutional environments. Based on the empirical findings, the key conclusions can be summarized as follows:

Economic freedom exerts a negative effect on bank profitability, particularly in countries with weaker regulatory capacity and financial supervision.

Internal capitalization (CAPTA) plays a stabilizing role by consistently moderating this adverse effect, while regulatory capital (CAR) has a weaker and less consistent impact.

The outcomes of liberalization are heterogeneous, depending on institutional quality, macroeconomic conditions, and capital strength, highlighting the need for contextualized approaches to reform.

These results carry both theoretical and practical implications. Theoretically, they challenge the conventional assumption that economic freedom uniformly enhances financial performance, suggesting instead a conditional relationship shaped by institutional safeguards and capital structures. Practically, the findings call for nuanced policy design in which financial openness is complemented by adequate capitalization and macroprudential regulation. To make these implications more explicit, they can be outlined as follows:

Theoretically, the study enriches the literature by showing that liberalization can have either stabilizing or destabilizing effects depending on capitalization and institutional conditions.

Practically, the results highlight that CAPTA serves as a reliable safeguard, whereas CAR requires careful calibration to balance profitability with systemic stability.

Policy frameworks should align liberalization with macroprudential tools, such as countercyclical buffers and liquidity requirements, to mitigate systemic risk and enhance resilience.

For banks’ capital management, the results recommend prioritizing strong internal equity buffers, maintaining prudent leverage ratios, and adopting dynamic provisioning practices to ensure both profitability and stability in liberalized markets.

This study is subject to some limitations, which also suggest promising avenues for future research:

The sample period ends in 2018, excluding more recent global shocks such as COVID-19; extending the sample to 2024 would allow a more comprehensive assessment of resilience under extreme conditions.

The reliance on World Bank sector-level data restricts granularity; future studies should use micro-level bank data to capture heterogeneity in capitalization strategies, competition, and risk-taking behavior.

Nonlinear and dynamic effects remain unexplored; further research should consider threshold models or regime-switching frameworks to capture potential turning points in the liberalization–performance relationship.

The study does not include the cost-to-income (C/I) ratio, which is widely used as an efficiency metric in the banking literature. Consistent coverage across 213 countries and the long time span made its inclusion infeasible. Future research with more harmonized datasets could incorporate C/I to enrich the set of performance indicators.

Institutional quality was only indirectly discussed; future work should explicitly integrate governance and supervisory indicators to better explain cross-country variation.

Overall, this study underscores that economic freedom cannot be evaluated in isolation but must be contextualized within institutional frameworks and financial architectures. Strong internal capital buffers emerge as a decisive factor in safeguarding performance and ensuring resilience, particularly in emerging markets where supervisory institutions remain underdeveloped.