The Extent and Efficiency of Credit Reallocation During Economic Downturns

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Size of Reallocation During Economic Downturns

2.2. Existence and Extent of Efficiency-Enhancing Resource Reallocation

3. Data

3.1. Data Sources

3.2. Construction of Credit Reallocation Measures

4. Empirical Approach

4.1. Extent of Credit Reallocation in Recessions

4.2. Existence and Extent of Efficiency-Enhancing Credit Reallocation

5. Results for the Extent of Credit Reallocation

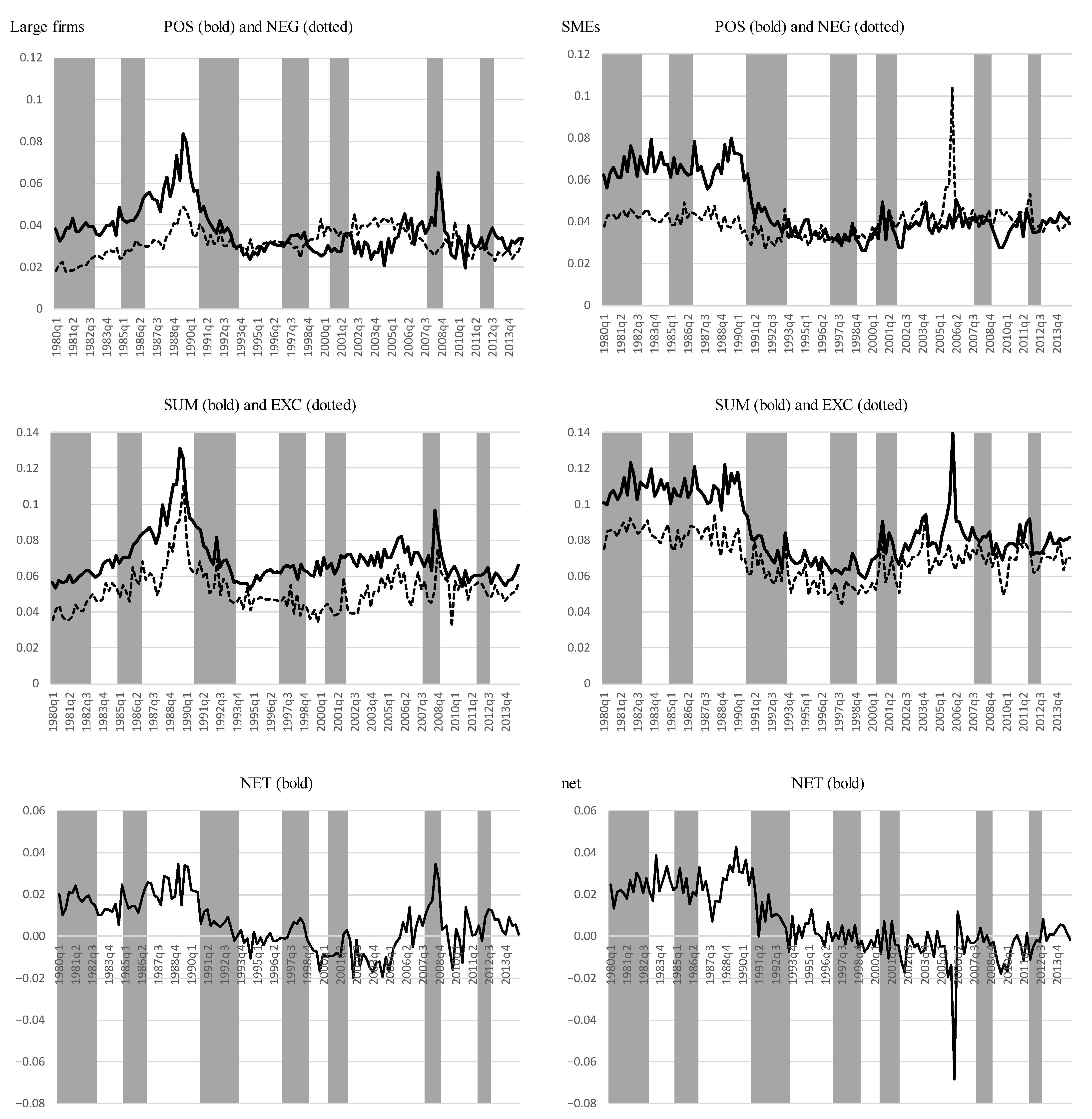

5.1. Extent of Credit Reallocation During Economic Downturns

5.2. Correlation Between Reallocation Measures and Economic Conditions

5.3. Vector Autoregression

6. Results for the Efficiency of Credit Reallocation

6.1. Summary Statistics

6.2. Baseline Estimation

6.3. Estimations Including Exiting Firms

6.4. Examination of the Reasons for Efficiency-Reducing Reallocation in the Lost Decade

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Firm-Level Data from the Quarterly Financial Statements Statistics of Corporations by Industry

Appendix B. Construction of the Data Set That Incorporates Firms’ Entries and Exits

Appendix C. Calculation of TFP

| Industry Code | Name of Industry |

| 1 | Agriculture, forestry, and fishery |

| 10 | Mining and quarrying of sand and gravel |

| 15 | Construction |

| 18 | Food processing |

| 20 | Textiles and clothing |

| 22 | Wood and wood products |

| 24 | Pulp and paper |

| 25 | Printing and allied industries |

| 26 | Chemicals |

| 27 | Petroleum and coal products |

| 30 | Ceramic products |

| 31 | Iron and steel |

| 32 | Non-ferrous metals |

| 33 | Metal products |

| 34 | General and precision machinery |

| 35 | Electrical and IT machinery |

| 36 | Automobiles and parts |

| 38 | Other transportation machinery |

| 39 | Other manufacturing |

| 40 | Wholesale |

| 49 | Retail |

| 59 | Real estate |

| 60 | Information and telecommunication |

| 61 | Land, water, and other transportation |

| 70 | Electricity, gas, heat supply, water |

| 75 | Other services |

Appendix D. Impact of Including Entering and Exiting Firms on the Extent of Credit Reallocation

| (a) Results for the observation period from FY2000 to FY2014. | |||||||||||

| Large firms | SMEs | ||||||||||

| POS | NEG | NET | SUM | EXC | POS | NEG | NET | SUM | EXC | ||

| 2000sQ1–2014Q4 (excl. entry & exit) | 0.033 | 0.034 | −0.000 | 0.067 | 0.051 | 2000sQ1–2014Q4 (excl. entry & exit) | 0.038 | 0.043 | −0.005 | 0.081 | 0.069 |

| 2000sQ1–2014Q4 (incl. entry & exit) | 0.033 | 0.035 | −0.001 | 0.068 | 0.053 | 2000sQ1–2014Q4 (incl. entry & exit) | 0.041 | 0.053 | −0.011 | 0.094 | 0.073 |

| H0: Excl. = Incl. | *** | ** | *** | *** | H0: Excl. = Incl. | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | |

| (b) Results when distinguishing between expansions and recessions. | |||||||||||

| Large firms | SMEs | ||||||||||

| 2001sQ1–2014Q4 (excl. entry & exit) | POS | NEG | NET | SUM | EXC | 2001sQ1–2014Q4 (excl. entry & exit) | POS | NEG | NET | SUM | EXC |

| Expansions | 0.032 | 0.034 | −0.002 | 0.066 | 0.052 | Expansions | 0.038 | 0.044 | −0.005 | 0.082 | 0.069 |

| Recessions | 0.037 | 0.031 | 0.006 | 0.068 | 0.050 | Recessions | 0.038 | 0.041 | −0.003 | 0.079 | 0.068 |

| Difference | −0.005 | 0.003 | −0.009 | −0.002 | 0.002 | Difference | −0.000 | 0.003 | −0.003 | 0.002 | 0.001 |

| H0: Expansions = Recessions | ** | * | *** | H0: Expansions = Recessions | |||||||

| 2001sQ1–2014Q4 (incl. entry & exit) | POS | NEG | NET | SUM | EXC | 2001sQ1–2014Q4 (incl. entry & exit) | POS | NEG | NET | SUM | EXC |

| Expansions | 0.032 | 0.035 | −0.003 | 0.067 | 0.054 | Expansions | 0.041 | 0.054 | −0.012 | 0.095 | 0.073 |

| Recessions | 0.037 | 0.033 | 0.004 | 0.070 | 0.051 | Recessions | 0.041 | 0.048 | −0.008 | 0.089 | 0.073 |

| Difference | −0.005 | 0.002 | −0.007 | −0.002 | 0.002 | Difference | 0.001 | 0.005 | −0.004 | 0.006 | 0.000 |

| H0: Expansions = Recessions | ** | ** | H0: Expansions = Recessions | ||||||||

Appendix E. Identification of Firms That Received Financial Assistance

| 1 | Note that there is also a strand of studies that examine credit reallocation among banks rather than among firms (Dell’Ariccia and Garibaldi 2005; Contessi and Francis 2013). |

| 2 | In addition to these studies, Li et al. (2023) and Saini and Ahmad (2024) empirically examine the characteristics and cyclicality of credit reallocation for China and India, respectively. More recently, Cuciniello (2024) investigated the credit allocation to businesses in Italy during the COVID-19 crisis. |

| 3 | All of these theoretical studies on resource reallocation focus on economic downturns. The focus on and interest in economic downturns among researchers date back to Schumpeter (1934), who argued that the main function of recessions lies in the liquidation and reallocation of resources. |

| 4 | For evidence regarding the duration of firm–bank relationships in Japan, among other countries, see Table 4.1 in the work of Degryse et al. (2009). |

| 5 | In a similar vein, this logic applies to firms with high leverage. In later analyses, we focus not only on small firms but also firms with low capital ratios to examine Hypothesis 3′. |

| 6 | Meanwhile, Bruche and Llobet (2014) argue that lenders’ limited liability may lead to possible distortions in the credit market that result in lenders providing financial assistance to nonviable borrowers in recessionary times. |

| 7 | Other studies have empirically examined the existence of zombie lending in countries other than Japan as well. In Europe, Bonfim et al. (2022) for Portugal, and Schivardi et al. (2022) for Italy show that unhealthy banks evergreened loans to zombie firms during the global financial crisis and subsequent sovereign debt crisis in Europe. In Asia, Chopra et al. (2021) show that undercapitalized banks increased lending to zombie firms after an asset quality review (AQR) in India, and Li and Ponticelli (2022) show that zombie lending occurred in areas with less specialized courts in China. Acharya et al. (2022) provide a more detailed survey of the recent research in this area. |

| 8 | The JIP database has been produced by RIETI in collaboration with the Institute of Economic Research at Hitotsubashi University. For details, see https://www.rieti.go.jp/en/database/jip.html. |

| 9 | This is because the QFSSC has covered this industry only for a limited period (since the first quarter of the fiscal year 2008). |

| 10 | Note that we have when the firm has zero debt outstanding at both time t − 1 and t. |

| 11 | Among the previous studies that examine the cyclicality of credit reallocation, Herrera et al. (2011), Dell’Ariccia and Garibaldi (2005), and Hyun and Minetti (2019) measure correlation coefficients, while Dell’Ariccia and Garibaldi (2005) adopt the VAR. Note, however, that both of these methods examine the extent of reallocation when the economy is in a short-term recession and not when it is experiencing long-term stagnation. |

| 12 | The DI is based on firms’ responses in the Bank of Japan’s Tankan survey regarding how they assess their current business conditions. The DI is obtained by subtracting the percentage of firms that say current conditions are unfavorable from the percentage of those saying that they are favorable, so that a higher DI indicates better business conditions. |

| 13 | Specifically, we follow Dell’Ariccia and Garibaldi (2005) in the way we extract the cyclical components. The cyclical component of each series is defined as the deviation of the logged original values of the credit reallocation measures and those of real GDP from their Hodrick–Prescott (HP) filtered logged values, with a smoothing parameter of 1600 that business cycle studies usually use for quarterly data. The cyclical component therefore is expressed in percentage terms. To ensure that the reallocation measures are expressed in percentage terms, we adjust the original values of the credit reallocation measures by multiplying them by . Note that we do not derive cyclical components for the net credit change, since it may take negative values and cannot be logged. |

| 14 | We limit the observation period to the end of the fiscal year of 2013 rather than the first quarter of 2014, which is the last period of our credit reallocation data, because some of the data we need for the calculation of our variables from the JIP database are unavailable. |

| 15 | In the VAR analysis, we perform Augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) tests to check for the stationarity in each time series, and the null of unit root is rejected in all cases. To select the lag length for each VAR, we adopt the lag-order selection statistics of Akaike’s information criterion (AIC). We performed lagrange multiplier (LM) tests for serial correlation on VAR residuals, and the null of no serial correlation was not rejected in all cases. |

| 16 | Throughout the two subsections focusing on correlation coefficients and VAR, we follow the convention and extract cyclical components by applying the HP filter to credit reallocation and real GDP. |

| 17 | Although the results are not shown, we checked the correlation matrix for all pairs of covariates used in the estimation in Section 6 to find no substantially correlated pairs of variables that possibly cause multicollinearity. |

| 18 | Caballero, Hoshi, and Kashyap use this procedure for the purpose of detecting zombie firms. There are several other studies that provide different definitions of zombie firms including Fukuda and Nakamura (2011), Imai (2016) and Goto and Wilbur (2019). However, we solely employ the procedure by Caballero, Hoshi, and Kashyap because their definition is simply based on the difference between a firm’s individual interest rate and the market prime rate, which is orthogonal to a change in a firm’s borrowing amount. |

| 19 | The TDB website states that the company holds information on about 4.2 million firms (see https://www.tdb.co.jp/info/topics/k170501.html, in Japanese, accessed 21 March 2021). Government statistics indicate that currently, there are 1.5 million corporations and 2.3 million proprietorships, totaling 3.8 million firms, which indicate that the TDB database covers almost the entire universe of Japanese firms. |

| 20 | The growth rate of debt () for an entering firm f is ( − 0)/0.5(+ 0) = 2 if > 0, and that for an exiting firm f is (0 − )/0.5(0 + ) = −2 if > 0. |

References

- Acharya, Viral V., Matteo Crosignani, Tim Eisert, and Sascha Steffen. 2022. Zombie Lending: Theoretical, International, and Historical Perspectives. Annual Review of Financial Economics 14: 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackerberg, Daniel A., Kevin Caves, and Garth Frazer. 2015. Identification Properties of Recent Production Function Estimators. Econometrica 83: 2411–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aw, Bee Yan, Xiaomin Chen, and Mark J. Roberts. 2001. Firm-Level Evidence on Productivity Differentials and Turnover in Taiwanese Manufacturing. Journal of Development Economics 66: 51–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, Ryan, and Boris Hofmann. 2018. The Rise of Zombie Firms: Causes and Consequences. BIS Quarterly Review 2018: 67–78. [Google Scholar]

- Barlevy, Gadi. 2003. Credit Market Frictions and the Allocation of Resources over the Business Cycle. Journal of Monetary Economics 50: 1795–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, Thorsten, Hans Degryse, Ralph De Haas, and Neeltje Van Horen. 2018. When Arm’s Length is too Far: Relationship Banking over the Credit Cycle. Journal of Financial Economics 127: 174–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becsi, Zsolt, Victor E. Li, and Ping Wang. 2005. Heterogeneous Borrowers, Liquidity, and the Search for Credit. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 29: 1331–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglöf, Erik, and Gérard Roland. 1997. Soft Budget Constraints and Credit Crunches in Financial Transition. European Economic Review 41: 807–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfim, Diana, Geraldo Cerqueiro, Hans Degryse, and Steven Ongena. 2022. On-Site Inspecting Zombie Lending. Management Science 69: 2547–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruche, Max, and Gerard Llobet. 2014. Preventing Zombie Lending. Review of Financial Studies 27: 923–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero, Ricardo J., and Mohamad Hammour. 1994. The Cleansing Effect of Recessions. American Economic Review 84: 1350–68. [Google Scholar]

- Caballero, Ricardo J., and Mohamad L. Hammour. 2005. The Cost of Recessions Revisited: A Reverse-Liquidationist View. Review of Economic Studies 72: 313–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero, Ricardo J., Takeo Hoshi, and Anil K. Kashyap. 2008. Zombie Lending and Depressed Restructuring in Japan. American Economic Review 98: 1943–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamley, Christophe, and Céline Rochon. 2011. From Search to Match: When Loan Contracts Are Too Long. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 43: 385–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, Yakshup, Krishnamurthy Subramanian, and Prasanna L. Tantri. 2021. Bank Cleanups, Capitalization, and Lending: Evidence from India. Review of Financial Studies 34: 4132–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contessi, Silvio, and Johanna L. Francis. 2013. U.S. Commercial Bank Lending through 2008:Q4: New Evidence from Gross Credit Flows. Economic Inquiry 51: 428–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuciniello, Vincenzo. 2024. Credit Allocation to Businesses in Italy amid the Covid-19 Crisis. Economics Letters 238: 111724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, Steven J., and John Haltiwanger. 1992. Gross Job Creation, Gross Job Destruction, and Employment Reallocation. Quarterly Journal of Economics 107: 819–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, Steven J., John Haltiwanger, and S. Schuh. 1996. Job Creation and Destruction. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Degryse, Hans, Moshe Kim, and Steven Ongena. 2009. Microeconometrics of Banking: Methods, Applications, and Results. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dell’Ariccia, Giovanni, and P. Garibaldi. 2005. Gross Credit Flows. The Review of Economic Studies 72: 665–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Den Haan, Wouter J., Garey Ramey, and Joel Watson. 2003. Liquidity Flows and Fragility of Business Enterprises. Journal of Monetary Economics 50: 1215–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewatripont, Mathias, and Eric Maskin. 1995. Credit and Efficiency in Centralized and Decentralized Economies. Review of Economic Studies 62: 541–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisfeldt, Andrea L., and Adriano A. Rampini. 2006. Capital Reallocation and Liquidity. Journal of Monetary Economics 53: 369–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ghoul, Sadok, Omrane Guedhami, Chuck Kwok, and Xiaolan Zheng. 2018. Zero-Leverage Puzzle: An International Comparison. Review of Finance 22: 1063–120. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, Lucia, Cheryl Grim, and John Haltiwanger. 2016. Reallocation in the Great Recession: Cleansing or Not? Journal of Labor Economics 34: S293–S331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukao, Kyoji, and Hyeog Ug Kwon. 2006. Why Did Japan’s TFP Growth Slow Down in the Lost Decade? An Empirical Analysis Based on Firm-Level Data of Manufacturing Firms. Japanese Economic Review 57: 195–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, Shin-ichi, and Jun-ichi Nakamura. 2011. Why Did ‘Zombie’ Firms Recover in Japan? The World Economy 34: 1124–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, Shin-ichi, Munehisa Kasuya, and Jun-ichi Nakajima. 2007. Hijojo Kigyo Ni ‘Oigashi’ Wa Sonzai Shita ka? [Did Forbearance Lending Exist among Non-listed Firms?]. Kin’yu Kenkyu [Monetary and Economic Studies] 26: 73–104. (In Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- Giannetti, Mariassunta, and Andrei Simonov. 2013. On the Real Effects of Bank Bailouts: Micro Evidence from Japan. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 5: 135–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good, David H., M. Ishaq Nadiri, and Robin C. Sickles. 1997. Index Number and Factor Demand Approaches to the Estimation of Productivity. In Handbook of Applied Econometrics: Vol. 2. Microeconometrics. Edited by M. Hashem Pesaran and Peter Schmidt. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Goto, Yasuo, and Scott Wilbur. 2019. Unfinished Business: Zombie Firms among SME in Japan’s Lost Decades. Japan and the World Economy 49: 105–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, Fumio, and Edward C. Prescott. 2002. The 1990s in Japan: A Lost Decade. Review of Economic Dynamics 5: 206–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, Ana Maria, Marek Kolar, and Raoul Minetti. 2011. Credit Reallocation. Journal of Monetary Economics 58: 551–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, Ana Maria, Marek Kolar, and Raoul Minetti. 2014. Credit Reallocation and the Macroeconomy. Mimeo: Michigan State University. [Google Scholar]

- Hoshi, Takeo, and Anil K. Kashyap. 2004. Japan’s Financial Crisis and Economic Stagnation. Journal of Economic Perspectives 18: 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, Junghwan, and Raoul Minetti. 2019. Credit Reallocation, Deleveraging, and Financial Crises. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 51: 1889–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, Kentaro. 2016. A Panel Study of Zombie SMEs in Japan: Identification, Borrowing and Investment Behavior. Journal of the Japanese and International Economies 39: 91–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, Rajkamal, José-Luis Peydró, Samuel da-Rocha-Lopes, and Antoinette Schoar. 2014. Interbank Liquidity Crunch and the Firm Credit Crunch: Evidence from the 2007–2009 Crisis. Review of Financial Studies 27: 347–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinsohn, James, and Amil Petrin. 2003. Estimating Production Functions Using Inputs to Control for Unobservables. Review of Economic Studies 70: 317–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Bo, and Jacopo Ponticelli. 2022. Going Bankrupt in China. Review of Finance 26: 449–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Xing, Xiangyu Ge, and Zhi Chen. 2023. The Characteristics Analysis of Credit Reallocation in China’s Corporate Sector: From the Volatility, Spatiality, Cyclicality and Efficiency Approach. Finance Research Letters 55: 103930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olley, Steven, and Ariel Pakes. 1996. The Dynamics of Productivity in the Telecommunications Equipment Industry. Econometrica 64: 1263–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passalacqua, Andrea, Paolo Angelini, Francesca Lotti, and Giovanni Soggia. 2021. The Real Effects of Bank Supervision: Evidence from On-Site Bank Inspections. In Bank of Italy Temi di Discussione (Working Paper) No. 1349. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3705558 (accessed on 19 October 2024).

- Peek, Joe, and Eric S. Rosengren. 2005. Unnatural Selection: Perverse Incentives and the Misallocation of Credit in Japan. American Economic Review 95: 1144–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramey, Valerie, and Matthew Shapiro. 1998. Capital Churning. Working Paper. San Diego: University of California. [Google Scholar]

- Saini, Seema, and Wasim Ahmad. 2024. Credit Creation, Credit Destruction and Credit Reallocation: Firm-level Evidence from India. Journal of Asian Economics 92: 101743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, Koji, Iichiro Uesugi, and Tsutomu Watanabe. 2010. Firm Age and the Evolution of Borrowing Costs: Evidence from Japanese Small Firms. Journal of Banking & Finance 34: 1970–81. [Google Scholar]

- Schivardi, Fabiano, Enrico Sette, and Guido Tabellini. 2022. Credit Misallocation during the European Financial Crisis. Economic Journal 132: 391–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumpeter, Joseph. A. 1934. Depressions. In Economics of the Recovery Program. Edited by Douglass V. Brown. New York: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Sette, Enrico, and Giorgio Gobbi. 2015. Relationship Lending during a Financial Crisis. Journal of the European Economic Association 13: 453–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| (a) Interest-bearing debt | Large firms | SMEs | ||||||||

| POS | NEG | NET | SUM | EXC | POS | NEG | NET | SUM | EXC | |

| Entire period | 0.038 | 0.032 | 0.006 | 0.069 | 0.052 | 0.047 | 0.040 | 0.007 | 0.086 | 0.070 |

| Expansions | 0.037 | 0.033 | 0.004 | 0.071 | 0.054 | 0.046 | 0.041 | 0.005 | 0.086 | 0.070 |

| Recessions | 0.038 | 0.029 | 0.010 | 0.067 | 0.049 | 0.048 | 0.038 | 0.010 | 0.087 | 0.070 |

| H0: Expansions = Recessions | *** | *** | ** | * | * | |||||

| Not Lost Decade | 0.040 | 0.031 | 0.009 | 0.071 | 0.054 | 0.051 | 0.043 | 0.008 | 0.094 | 0.075 |

| Lost Decade | 0.032 | 0.033 | 0.000 | 0.065 | 0.048 | 0.037 | 0.034 | 0.003 | 0.071 | 0.059 |

| H0: Lost Decade = Not-Lost Decade | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | ** | *** | *** | |

| (b) Bank loans | Large firms | SMEs | ||||||||

| POS | NEG | NET | SUM | EXC | POS | NEG | NET | SUM | EXC | |

| Entire period | 0.040 | 0.035 | 0.005 | 0.075 | 0.060 | 0.049 | 0.042 | 0.006 | 0.091 | 0.074 |

| Expansions | 0.039 | 0.037 | 0.002 | 0.076 | 0.062 | 0.048 | 0.043 | 0.005 | 0.091 | 0.073 |

| Recessions | 0.041 | 0.031 | 0.009 | 0.072 | 0.056 | 0.050 | 0.041 | 0.009 | 0.091 | 0.074 |

| H0: Expansions = Recessions | *** | *** | ** | *** | ** | * | ||||

| Not Lost Decade | 0.043 | 0.035 | 0.008 | 0.078 | 0.061 | 0.054 | 0.045 | 0.009 | 0.099 | 0.079 |

| Lost Decade | 0.033 | 0.034 | -0.001 | 0.067 | 0.056 | 0.038 | 0.037 | 0.001 | 0.075 | 0.062 |

| H0: Lost Decade = Not-Lost Decade | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | |

| Large firms | |||||||||

| GDP(t − 4) | GDP(t − 3) | GDP(t − 2) | GDP(t − 1) | GDP(t) | GDP(t + 1) | GDP(t + 2) | GDP(t + 3) | GDP(t + 4) | |

| POS | 0.510 | 0.442 | 0.349 | 0.183 | −0.010 | −0.067 | 0.019 | −0.049 | −0.000 |

| *** | *** | *** | ** | ||||||

| NEG | −0.198 | −0.155 | −0.190 | −0.130 | 0.006 | 0.071 | 0.179 | 0.264 | 0.295 |

| ** | * | ** | ** | *** | *** | ||||

| SUM | 0.305 | 0.279 | 0.200 | 0.086 | 0.009 | −0.065 | 0.121 | 0.081 | 0.155 |

| *** | *** | ** | * | ||||||

| EXC | 0.253 | 0.136 | 0.052 | −0.014 | −0.067 | 0.027 | 0.070 | 0.166 | 0.187 |

| *** | * | ** | |||||||

| DI(t − 4) | DI(t − 3) | DI(t − 2) | DI(t − 1) | DI(t) | DI(t + 1) | DI(t + 2) | DI(t + 3) | DI(t + 4) | |

| POS | 0.408 | 0.362 | 0.280 | 0.164 | 0.083 | 0.017 | 0.011 | 0.014 | 0.011 |

| *** | *** | *** | * | ||||||

| NEG | 0.048 | 0.083 | 0.134 | 0.178 | 0.211 | 0.231 | 0.235 | 0.228 | 0.204 |

| ** | ** | *** | *** | *** | ** | ||||

| SUM | 0.370 | 0.343 | 0.301 | 0.236 | 0.193 | 0.137 | 0.136 | 0.142 | 0.130 |

| *** | *** | *** | *** | ** | * | ||||

| EXC | 0.257 | 0.256 | 0.219 | 0.179 | 0.134 | 0.126 | 0.121 | 0.133 | 0.118 |

| *** | *** | *** | ** | ||||||

| SMEs | |||||||||

| GDP(t − 4) | GDP(t − 3) | GDP(t − 2) | GDP(t − 1) | GDP(t) | GDP(t + 1) | GDP(t + 2) | GDP(t + 3) | GDP(t + 4) | |

| POS | 0.166 | 0.221 | 0.237 | 0.264 | 0.228 | 0.208 | 0.195 | 0.175 | 0.210 |

| * | *** | *** | *** | *** | ** | ** | ** | ** | |

| NEG | −0.049 | −0.039 | −0.043 | 0.031 | 0.064 | 0.117 | 0.150 | 0.166 | 0.205 |

| * | * | ** | |||||||

| SUM | 0.058 | 0.095 | 0.104 | 0.174 | 0.178 | 0.190 | 0.212 | 0.222 | 0.255 |

| ** | ** | ** | ** | *** | *** | ||||

| EXC | 0.108 | 0.133 | 0.084 | 0.121 | 0.114 | 0.141 | 0.114 | 0.081 | 0.145 |

| * | * | ||||||||

| DI(t − 4) | DI(t − 3) | DI(t − 2) | DI(t − 1) | DI(t) | DI(t + 1) | DI(t + 2) | DI(t + 3) | DI(t + 4) | |

| POS | 0.319 | 0.370 | 0.371 | 0.334 | 0.254 | 0.205 | 0.153 | 0.120 | 0.091 |

| *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | ** | * | |||

| NEG | 0.110 | 0.110 | 0.129 | 0.145 | 0.131 | 0.119 | 0.118 | 0.112 | 0.103 |

| * | |||||||||

| SUM | 0.253 | 0.283 | 0.297 | 0.280 | 0.231 | 0.197 | 0.168 | 0.143 | 0.119 |

| *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | ** | ** | * | ||

| EXC | 0.180 | 0.207 | 0.211 | 0.212 | 0.154 | 0.119 | 0.091 | 0.074 | 0.069 |

| ** | ** | ** | ** | * | |||||

| Entire Period | Before Lost Decade | Lost Decade | After Lost Decade | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean | sd | min | max | mean | sd | min | max | mean | sd | min | max | mean | sd | min | max | |

| Debt_growth | −0.007 | 0.363 | −2.000 | 2.000 | 0.011 | 0.359 | −2.000 | 2.000 | −0.006 | 0.344 | −2.000 | 2.000 | −0.019 | 0.381 | −2.000 | 2.000 |

| BankLoan_growth | −0.010 | 0.376 | −2.000 | 2.000 | 0.007 | 0.393 | −2.000 | 2.000 | −0.008 | 0.377 | −2.000 | 2.000 | −0.023 | 0.364 | −2.000 | 2.000 |

| lnTFPt−1 | −0.146 | 0.412 | −3.740 | 1.816 | −0.116 | 0.288 | −2.995 | 1.548 | −0.178 | 0.413 | −3.740 | 1.201 | −0.137 | 0.474 | −3.081 | 1.816 |

| GDP_hp | 0.000 | 0.015 | −0.060 | 0.036 | 0.001 | 0.012 | −0.031 | 0.029 | −0.000 | 0.013 | −0.023 | 0.026 | −0.000 | 0.018 | −0.060 | 0.036 |

| DI | −10.222 | 20.094 | −49.000 | 41.000 | 3.931 | 21.800 | −29.000 | 41.000 | −20.565 | 18.033 | −49.000 | 31.000 | −10.030 | 13.954 | −46.000 | 8.000 |

| lnAssetst−1 | 8.578 | 2.036 | 2.398 | 13.823 | 8.395 | 2.025 | 2.398 | 13.822 | 8.754 | 2.003 | 2.398 | 13.823 | 8.535 | 2.061 | 2.398 | 13.823 |

| Sales_growtht−1 | 0.109 | 0.611 | −0.933 | 8.725 | 0.113 | 0.581 | −0.933 | 8.720 | 0.110 | 0.627 | −0.933 | 8.725 | 0.106 | 0.615 | −0.933 | 8.716 |

| ROAt−1 | 0.009 | 0.035 | −0.316 | 0.246 | 0.013 | 0.034 | −0.315 | 0.246 | 0.007 | 0.035 | −0.316 | 0.246 | 0.008 | 0.036 | −0.316 | 0.246 |

| Capital_ratiot−1 | 0.307 | 0.292 | −1.427 | 1.000 | 0.234 | 0.248 | −1.426 | 1.000 | 0.282 | 0.288 | −1.427 | 1.000 | 0.378 | 0.307 | −1.426 | 1.000 |

| Observations | 1,349,175 | 347,179 | 484,597 | 517,399 | ||||||||||||

| Dependent variable: Debt_growth | ||||||||||

| Estimation method: OLS | ||||||||||

| Entire period | Before Lost Decade | Lost Decade | After Lost Decade | |||||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | |

| lnTFPt−1 | 0.00199 ** | 0.00150 | 0.00202 ** | 0.00471 *** | 0.0155 *** | 0.0160 *** | −0.00323 ** | −0.00340 ** | 0.00521 *** | 0.00519 *** |

| (0.000929) | (0.000930) | (0.000930) | (0.00110) | (0.00266) | (0.00265) | (0.00155) | (0.00155) | (0.00142) | (0.00142) | |

| GDP_hp | 0.116 *** | 0.121 *** | 0.208 *** | 0.251 *** | −0.0119 | |||||

| (0.0215) | (0.0244) | (0.0502) | (0.0386) | (0.0299) | ||||||

| DI | 0.000279 *** | 0.000313 *** | 6.33e−05 ** | 0.000297 *** | 4.55e−06 | |||||

| (1.56e−05) | (1.80e−05) | (2.83e−05) | (2.81e−05) | (3.87e−05) | ||||||

| lnTFPt−1*GDP_hp | 0.0327 | |||||||||

| (0.0475) | ||||||||||

| lnTFPt−1*DI | 0.000239 *** | |||||||||

| (3.93e−05) | ||||||||||

| lnAssetst−1 | −0.00108 *** | −0.00101 *** | −0.00108 *** | −0.00104 *** | −0.000424 | −0.000523 | −0.00113 *** | −0.00113 *** | −0.000761 *** | −0.000760 *** |

| (0.000157) | (0.000157) | (0.000157) | (0.000157) | (0.000319) | (0.000319) | (0.000258) | (0.000258) | (0.000257) | (0.000257) | |

| Sales_growtht−1 | 0.00339 *** | 0.00345 *** | 0.00339 *** | 0.00343 *** | 0.00167 | 0.00163 | 0.00550 *** | 0.00552 *** | 0.00297 *** | 0.00296 *** |

| (0.000629) | (0.000629) | (0.000629) | (0.000629) | (0.00124) | (0.00124) | (0.000944) | (0.000944) | (0.00111) | (0.00111) | |

| ROAt−1 | −0.398 *** | −0.407 *** | −0.398 *** | −0.409 *** | −0.365 *** | −0.365 *** | −0.402 *** | −0.408 *** | −0.514 *** | −0.514 *** |

| (0.0125) | (0.0125) | (0.0125) | (0.0126) | (0.0257) | (0.0257) | (0.0210) | (0.0211) | (0.0202) | (0.0202) | |

| Capital_ratiot−1 | 0.00578 *** | 0.00642 *** | 0.00578 *** | 0.00653 *** | 0.0331 *** | 0.0330 *** | 0.00425 ** | 0.00472 ** | 0.0151 *** | 0.0151 *** |

| (0.00119) | (0.00119) | (0.00119) | (0.00119) | (0.00317) | (0.00318) | (0.00201) | (0.00201) | (0.00178) | (0.00178) | |

| Constant | −0.00320 | −0.00141 | −0.00317 | −0.000717 | 0.00630 | 0.00694 | −0.00713 * | −0.00130 | −0.0166 *** | −0.0166 *** |

| (0.00268) | (0.00268) | (0.00268) | (0.00269) | (0.00515) | (0.00515) | (0.00408) | (0.00411) | (0.00479) | (0.00480) | |

| Industry FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 1,349,175 | 1,349,175 | 1,349,175 | 1,349,175 | 347,179 | 347,179 | 484,597 | 484,597 | 517,399 | 517,399 |

| R-squared | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 |

| Dependent variable: BankLoan_growth | ||||||||||

| Estimation method: OLS | ||||||||||

| Entire period | Before Lost Decade | Lost Decade | After Lost Decade | |||||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | |

| lnTFPt−1 | 0.00363 *** | 0.00324 *** | 0.00365 *** | 0.00511 *** | 0.0159 *** | 0.0164 *** | −0.00144 | −0.00159 | 0.00629 *** | 0.00631 *** |

| (0.000916) | (0.000917) | (0.000917) | (0.00109) | (0.00275) | (0.00275) | (0.00158) | (0.00158) | (0.00133) | (0.00133) | |

| GDP_hp | 0.0941 *** | 0.0976 *** | 0.255 *** | 0.208 *** | −0.0450 | |||||

| (0.0216) | (0.0240) | (0.0558) | (0.0423) | (0.0282) | ||||||

| DI | 0.000223 *** | 0.000242 *** | 3.21e−05 | 0.000253 *** | −4.92e−05 | |||||

| (1.69e−05) | (1.92e−05) | (3.12e−05) | (3.10e−05) | (3.71e−05) | ||||||

| lnTFPt−1*GDP_hp | 0.0255 | |||||||||

| (0.0469) | ||||||||||

| lnTFPt−1*DI | 0.000139 *** | |||||||||

| (4.12e−05) | ||||||||||

| lnAssetst−1 | −0.00151 *** | −0.00146 *** | −0.00151 *** | −0.00147 *** | −0.00154 *** | −0.00162 *** | −0.000685 ** | −0.000686 ** | −0.00173 *** | −0.00174 *** |

| (0.000167) | (0.000168) | (0.000167) | (0.000168) | (0.000364) | (0.000362) | (0.000284) | (0.000284) | (0.000254) | (0.000254) | |

| Sales_growtht−1 | 0.00383 *** | 0.00388 *** | 0.00383 *** | 0.00387 *** | 0.00314 ** | 0.00312 ** | 0.00504 *** | 0.00506 *** | 0.00362 *** | 0.00361 *** |

| (0.000633) | (0.000633) | (0.000633) | (0.000633) | (0.00129) | (0.00129) | (0.000974) | (0.000973) | (0.00107) | (0.00107) | |

| ROAt−1 | −0.260 *** | −0.267 *** | −0.260 *** | −0.268 *** | −0.303 *** | −0.302 *** | −0.298 *** | −0.303 *** | −0.291 *** | −0.291 *** |

| (0.0120) | (0.0120) | (0.0120) | (0.0120) | (0.0263) | (0.0263) | (0.0205) | (0.0206) | (0.0180) | (0.0180) | |

| Capital_ratiot−1 | 0.0120 *** | 0.0125 *** | 0.0120 *** | 0.0126 *** | 0.0324 *** | 0.0324 *** | 0.0126 *** | 0.0130 *** | 0.0236 *** | 0.0236 *** |

| (0.00122) | (0.00122) | (0.00122) | (0.00122) | (0.00345) | (0.00346) | (0.00215) | (0.00215) | (0.00172) | (0.00172) | |

| Constant | −0.00942 *** | −0.00800 *** | −0.00940 *** | −0.00759 *** | 0.00354 | 0.00430 | −0.0209 *** | −0.0160 *** | −0.0167 *** | −0.0172 *** |

| (0.00289) | (0.00289) | (0.00289) | (0.00290) | (0.00582) | (0.00582) | (0.00473) | (0.00475) | (0.00475) | (0.00476) | |

| Industry FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 1,349,179 | 1,349,179 | 1,349,179 | 1,349,179 | 347,181 | 347,181 | 484,598 | 484,598 | 517,400 | 517,400 |

| R-squared | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Dependent variable: Debt_growth | Comparison of means between surviving and exiting firms | |||||||||||

| Estimation method: OLS | ||||||||||||

| Post-lost decade | ||||||||||||

| Including exiting firms | Excluding exiting firms | Surviving firms | Exiting firms | Difference | ||||||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | ||

| lnTFPt−1 | 0.00454 ** | 0.00440 ** | 0.00448 ** | 0.00409 * | 0.00369 * | 0.00364 * | 0.00365 * | 0.00429 * | −0.0744614 | −0.0856043 | 0.011 | |

| (0.00208) | (0.00208) | (0.00208) | (0.00245) | (0.00196) | (0.00196) | (0.00196) | (0.00232) | |||||

| GDP_hp | 0.0282 | 0.0251 | 0.0244 | 0.0227 | −0.00003 | −0.0003633 | 0.000 | |||||

| (0.0384) | (0.0403) | (0.0371) | (0.0391) | |||||||||

| DI | 9.83e−05 ** | 9.61e−05 * | 4.26e−05 | 4.73e−05 | −10.10044 | −11.9027 | 1.802 | *** | ||||

| (4.92e−05) | (5.23e−05) | (4.72e−05) | (5.06e−05) | |||||||||

| lnTFPt−1*GDP_hp | −0.0454 | −0.0250 | ||||||||||

| (0.0843) | (0.0797) | |||||||||||

| lnTFPt−1*DI | −2.64e−05 | 5.61e−05 | ||||||||||

| (0.000109) | (0.000101) | |||||||||||

| lnAssetst−1 | 0.00221 *** | 0.00223 *** | 0.00222 *** | 0.00223 *** | 0.000588 | 0.000595 | 0.000590 | 0.000591 | 9.235 | 8.294 | 0.941 | *** |

| (0.000414) | (0.000414) | (0.000414) | (0.000414) | (0.000398) | (0.000398) | (0.000398) | (0.000398) | |||||

| Sales_growtht−1 | 0.00761 *** | 0.00762 *** | 0.00762 *** | 0.00762 *** | 0.00749 *** | 0.00749 *** | 0.00749 *** | 0.00750 *** | 0.087 | 0.068 | 0.019 | |

| (0.00164) | (0.00164) | (0.00164) | (0.00164) | (0.00161) | (0.00161) | (0.00161) | (0.00161) | |||||

| ROAt−1 | −0.603 *** | −0.605 *** | −0.603 *** | −0.605 *** | −0.649 *** | −0.650 *** | −0.649 *** | −0.650 *** | 0.009 | 0.001 | 0.008 | *** |

| (0.0330) | (0.0330) | (0.0330) | (0.0331) | (0.0317) | (0.0317) | (0.0317) | (0.0317) | |||||

| Capital_ratiot−1 | 0.0419 *** | 0.0419 *** | 0.0419 *** | 0.0419 *** | 0.0222 *** | 0.0222 *** | 0.0222 *** | 0.0222 *** | 0.382 | 0.200 | 0.182 | *** |

| (0.00273) | (0.00273) | (0.00273) | (0.00273) | (0.00254) | (0.00254) | (0.00254) | (0.00254) | |||||

| Constant | −0.0489 *** | −0.0481 *** | −0.0489 *** | −0.0481 *** | −0.0257 *** | −0.0253 *** | −0.0257 *** | −0.0252 *** | ||||

| (0.00912) | (0.00913) | (0.00913) | (0.00914) | (0.00866) | (0.00867) | (0.00866) | (0.00868) | |||||

| Industry FE | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | ||||

| Observations | 360,121 | 360,121 | 360,121 | 360,121 | 358,641 | 358,641 | 358,641 | 358,641 | 358,641 | 1480 | ||

| R-squared | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sakai, K.; Uesugi, I. The Extent and Efficiency of Credit Reallocation During Economic Downturns. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2024, 17, 574. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm17120574

Sakai K, Uesugi I. The Extent and Efficiency of Credit Reallocation During Economic Downturns. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2024; 17(12):574. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm17120574

Chicago/Turabian StyleSakai, Koji, and Iichiro Uesugi. 2024. "The Extent and Efficiency of Credit Reallocation During Economic Downturns" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 17, no. 12: 574. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm17120574

APA StyleSakai, K., & Uesugi, I. (2024). The Extent and Efficiency of Credit Reallocation During Economic Downturns. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17(12), 574. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm17120574