Abstract

Purpose—This paper investigates the role of forensic accounting skills in enhancing auditor self-efficacy towards fraud detection in Indonesia. It also examines the moderating effect of the implementation of Generalized Audit Software (GAS) and the whistleblowing system on the relationship between accounting and auditing skills and auditor self-efficacy, as well as their combined role in enhancing fraud detection. Methodology—A cross-sectional survey was conducted with 537 external auditors in Indonesia. Data were analyzed using multiple linear regression with moderation models, employing WarpPLS 8.0 software. Findings—The results indicate that practical communication skills, psychosocial skills, and accounting and auditing skills significantly enhance auditor self-efficacy. However, technical and analytical skills do not show a significant effect on auditor self-efficacy. Furthermore, auditor self-efficacy is found to have a direct and significant impact on fraud detection. This study also reveals that implementing GAS moderates the relationship between auditor self-efficacy and fraud detection, whereas the whistleblowing system does not demonstrate a significant moderating effect. Novelty—This study contributes to the literature by highlighting the role of forensic accounting skills and the implementation of GAS in enhancing auditor self-efficacy and fraud detection in the Indonesian auditing context.

1. Introduction

Fraud is a global issue that remains a significant challenge for businesses and governments worldwide. For example, the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE 2022) highlights that fraud costs organizations billions annually, making it a critical subject for research and discussion. The implications in the business world are that this fraudulent act is very detrimental to the companies (Rustiarini et al. 2021). Activities related to fraud that are generally unknown in a company determine a series of deviations and prohibited actions characterized by deliberate fraud carried out by a fraudster (Sánchez-Aguayo et al. 2021). Fraudulent activities can result in significant financial losses, weaken investor confidence, and hinder economic development growth (Al Natour et al. 2023). Therefore, fraud must be detected as early as possible not to have an even more significant impact.

ACFE (2022) has released the results of a survey on fraud. The results showed that the Asia Pacific region was ranked third with 183 fraud cases. In the survey, the most common form of fraud was corruption, with an average loss due to fraud reaching USD 200,000. According to Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) 2023, Indonesia is ranked 105th globally, indicating relatively high perceptions of corruption compared to other Southeast Asian nations. The Indonesian CPI, which is part of the global CPI compiled by Transparency International, ranks countries based on the perceived levels of public sector corruption. The index uses a scale from 0 (highly corrupt) to 100 (very clean). In the latest report, Indonesia is ranked 105th globally, reflecting ongoing concerns about corruption despite efforts to combat it. In the last five years, the value of the Indonesian Corruption Perception Index has tended to decline. In 2019, Indonesia’s Corruption Perception Index was 40/100. This value decreased in 2022 to 34/100. In early 2024, Transparency International released Indonesia’s latest Corruption Perception Index with a score of 34/100. This indicates that the government’s efforts to handle corruption cases have failed. Fraud is a rapidly increasing phenomenon worldwide, and organizations need to be firm in their fraud detection and prevention tools (Saluja 2024). Fraud can be detected through the audit process. Determining fraudulent acts and providing appropriate recommendations for prevention can be done through comprehensive audit activities (Saragih and Dewayanto 2023). This approach has proven to be very useful in identifying fraudulent financial reporting, which can significantly disrupt the reliability and efficiency of financial markets (Daraojimba et al. 2023).

Forensic accounting skills play a vital role in fraud detection, especially in countries with high rates of financial violations, including Indonesia. Forensic accounting involves the application of specialized knowledge and investigative skills to identify and analyze financial discrepancies and fraud (ACFE 2022), making it a crucial tool in addressing financial misconduct in such contexts. However, the effectiveness of forensic accounting in fraud detection can be influenced by various factors, including the use of Generalized Audit Software (GAS) and the implementation of a whistleblowing system (WBS). Research indicates that forensic accounting alone may not significantly impact fraud detection unless complemented by other mechanisms. A study found that forensic accounting did not directly affect fraud detection, suggesting that forensic accountants are not fully integrated into fraud detection efforts (Hassan et al. 2023). On the other hand, investigative audit capabilities and auditor experience significantly impact fraud detection, highlighting the importance of comprehensive audit skills and knowledge in identifying fraudulent activities. In fraud detection, an auditor needs to master forensic accounting (Al Natour et al. 2023). Forensic accounting services utilize the specialized skills of public accountants, auditing, tax economics, fraud detection, and other skills to conduct various types of investigations and communicate findings in a courtroom or administrative environment (Elisha et al. 2020). These specialized skills in forensic accounting include technical and analytical skills, practical communication skills, psychosocial skills, and accounting and auditing skills (Al Natour et al. 2023). Many organizations that conduct audits are computerized, creating new possibilities and risks for the auditor’s work (Pathmasiri and Piyananda 2021). Audit software is developed to automate processes and improve data analysis and audit work (Alotaibi and Alnesafi 2023).

In recent years (2015–2020), audits have used computer-assisted audit techniques (CAATs) (Siew et al. 2020). CAATs are the use of computers in audit activities to obtain audit evidence, making it easier for auditors to collect and analyze electronic-based information (Handoko et al. 2020). GAS is the most popular form of audit technology in the CAATs category (Pathmasiri and Piyananda 2021). This approach allows auditors to access and retrieve various data files into a computer and perform tests as needed (Handoko et al. 2022). After fraud is identified and detected, fraudulent actions can be disclosed through the whistleblowing system. WBSs allow employees and stakeholders to report fraud or unethical behavior anonymously, which serves as a valuable source of information for forensic accountants. By enabling early detection of potential problems, WBSs support targeted investigations, increasing the efficiency of forensic accounting in uncovering fraudulent activities. This integration enhances fraud detection by providing actionable insights to auditors, thereby facilitating a more effective investigation process. The synergy between WBS and forensic accounting is particularly relevant in Indonesia, where evolving regulations aim to strengthen corporate governance and address financial crime. This whistleblowing system has an important role that can be a medium for revealing illegal acts, unethical behavior, or other actions that occur in the companies and are detrimental to the organization (Gaaya et al. 2017). The whistleblowing system allows individuals to report fraudulent practices without fear or intimidation. Thus, the companies can immediately stop fraudulent practices and maintain financial integrity (Oktaviany and Reskino 2023).

Self-efficacy refers to an individual’s belief in their ability to successfully perform a task or achieve a specific goal (Bandura 1977). Auditor self-efficacy is defined as the auditor’s level of confidence in their ability to detect, analyze, and uncover fraud in the audit process. This concept includes several aspects, such as: Confidence in Technical Ability: The auditor is confident that they can use technical knowledge and skills to detect fraud. Confidence in the Decision-Making Process: The auditor feels capable of making the right decision based on the evidence found. Next, Psychological Resilience: The auditor is confident in overcoming challenges or pressures that may arise during the investigation. According to Bandura (1977), self-efficacy reduces an individual’s ability to carry out tasks efficiently. Research on auditor self-efficacy in detecting fraud has previously been conducted. The results of the study Rustiarini et al. (2021); Atmadja et al. (2019); Milanie et al. (2019); Al Natour et al. (2023) stated that Auditor Self-Efficacy has a significant influence on fraud detection. Meanwhile, according to the results of a study by Azzahroh et al. (2020), auditor self-efficacy has no significant relationship with fraud detection. The difference in research results made researchers conduct further research on the relationship between auditor self-efficacy and fraud detection. Based on the existing phenomena and research results, this study aims to analyze and test the direct and indirect impacts between auditor self-efficacy and fraud detection. This study aims to investigate the role of forensic accounting and risk management in detecting fraud in Indonesia, with a focus on the moderating role of GAS and WBS in this context. The respondents surveyed in this study were external auditors who were experienced in forensic audit practices in Indonesia. The selection of external auditors as respondents is very relevant, because they have an objective perspective and can provide insight into the influence of GAS and WBS on fraud detection in the public and private sectors in Indonesia. Therefore, this study focuses on testing the direct effect of auditor self-efficacy on fraud detection. At the same time, the impact of the indirect relationship is integrated from General Audit Software and whistleblowing systems (WBSs) as a moderating variable to measure the effect of auditor self-efficacy on fraud detection.

2. Literature Review

The fraud triangle theory, introduced by Donald Cressey (1953), is an important foundation in understanding the main causes of fraud in organizations, namely through three elements: pressure, opportunity, and rationalization. In the context of research on Forensic Accounting and Risk Management: The Moderating Role of GAS and WBS on fraud detection in Indonesia, this theory provides a conceptual framework to explain how forensic accounting, risk management, GAS (Generalized Audit Software), and WBS (whistleblowing system) can play a role in detecting and mitigating fraud risks. Pressure elements often arise due to urgent financial needs, high performance targets, or difficult personal situations, which encourage individuals to commit fraud. In this case, forensic accounting helps detect financial patterns that reflect such pressure through comprehensive financial data analysis, while risk management identifies early risks and offers mitigation to prevent excessive pressure that can trigger fraud. Furthermore, opportunities to commit fraud usually occur due to weaknesses in the internal control system or lack of supervision. GAS plays an important role in narrowing this opportunity by providing technological tools that can efficiently analyze transaction data and detect suspicious anomalies. In addition, WBS allows early reporting of suspicious behavior by employees or related parties, so that opportunities for fraud can be minimized. Finally, rationalization refers to the justification made by individuals to legitimize their fraudulent actions. Forensic accounting can reveal this rationalization pattern through in-depth analysis of financial records and interviews with the parties involved. WBS also plays a role in providing additional perspectives from reporters who may know the perpetrator’s motives and behavior, so that this rationalization can be identified earlier.

In the Indonesian context, where the level of fraud is relatively high, the fraud triangle theory is an important framework for understanding how the elements that cause fraud can be identified and intervened. Forensic accounting supported by GAS and WBS provides a holistic approach to detecting and preventing fraud more effectively. This combination not only strengthens the corporate governance system but also ensures transparency and accountability within the organization, in line with government and regulator efforts to strengthen financial practices in Indonesia.

3. Hypothesis Development

Technical and Analytical Skills (TASs), which involve the ability to analyze complex financial data, interpret financial transactions, and use specialized training tools to identify and analyze financial transactions, including anomalies that may indicate fraudulent activity, maintain a critical mindset in pursuing forensic excellence. According to Al Natour et al. (2023), TAS is a crucial component of the auditor’s forensic investigation team, which requires extensive research to detect fraud. The study conducted by McMullen and Sanchez (2010) and Chukwu et al. (2019) highlights the importance of TAS in identifying the suspect in a financial transaction. It indicates that decreasing TAS can result in ineffective and short-lived forensic investigations.

Furthermore, having a more effective auditor’s signature, a term used to describe an auditor’s unique approach and style, is linked to having a stronger TAS. A study reveals that auditors with strong analytical skills, such as TAS, consistently have higher self-efficacy, positively impacting their ability to create informative reports during audits. According to the study conducted by Albawwat et al. (2021), for example, auditors with high levels of personal effectiveness perform better when creating accurate audit reports. Research by S. Cilliers (2023) indicates that emotional intelligence as a moderator that strengthens this bond positively impacts audit quality. Furthermore, Plumlee et al. stress the importance of metacognitive training, including analytics’ tendency to diverge and converge, to increase auditor productivity at the required level in the analysis procedure.

Additionally, Chukwu et al. (2019) point out that emotional intelligence and task complexity, when combined with emotional intelligence, negatively impact auditor evaluations and highlight the need for emotional intelligence analysts to handle complex tasks and enhance audit quality. The study conducted by Masruroh and Carolina (2022) indicates that professional expertise, including analysis, significantly positively affects an auditor’s ability to detect and validate fraud. Furthermore, research by Brody et al. (2020) reveals that emotional intelligence, whether in the form of emotional intelligence or self-efficacy, positively affects auditor work performance. It also indicates that the effectiveness of analysis can be increased if it is linked to emotional intelligence. Susanti (2023) said that self-efficacy also affects job satisfaction and turnover intentions. Auditors seek better job opportunities and challenges, which may be driven by their confidence in their analytical abilities and desire for professional growth. This study highlights the importance of analytic skills, a term used to describe the combination of analytical skills and expertise, in developing the auditor’s effectiveness, improving work efficiency, the quality of putting in work, and the ability to adjust to changing circumstances in the auditing profession.

H1:

Technical and analytical skills have a positive effect on auditor’s self-efficacy.

Practical communication skills (PCSs) are a critical competency every forensic accountant should possess McMullen and Sanchez (2010). Clearly and concisely communicating ideas to various stakeholders—such as lawyers, law enforcement agencies, and other professionals—is crucial. Forensic experts must record incident reports, prepare presentations, and provide evidence in court. However, the actual value of PCSs lies in its ability to ensure that research results are understood and empathetically considered from the client’s perspective. Chukwu et al. (2019) conducted research highlighting the importance of communication skills for forensic experts to clearly and concisely report their findings. According to Smith (2005), effective communication skills are crucial for auditors to understand client perspectives, provide accurate and comprehensive information, and establish strong relationships with clients.

Practical communication skills also strongly relate to the auditor’s effectiveness, which is their self-belief in carrying out the audit task. The Auditor Self-Efficacy Scale (ASE) is a sub-scale measuring technical proficiency, technological adaptation, and interpersonal communication. It emphasizes the importance of personal efficiency in auditing competence. Research indicates that communication skills training can improve auditors’ efficiency and ability to collaborate and form bonds with coworkers and superiors (Rydzak et al. 2023). Effectiveness positively impacts audit quality, and emotional intelligence serves as a moderator to enhance this effect (Pinatik 2021). High communication needs have been identified since the 1980s, with research indicating that these needs are frequently not met by the general public, indicating the need for intervention to increase communication efficiency (Rydzak et al. 2023).

Efficiency in self-reporting also affects audit results and employee quality; additionally, self-reporting efficiency, in conjunction with goal orientation, has a positive impact on the audit process (Salehi and Dastanpoor 2021). During the COVID-19 pandemic, virtual audits and emotional assessments evaluated the auditor’s effectiveness, leading to lower auditor effectiveness in unfavorable conditions (Pramana et al. 2019). Workplace performance, motivation, and daily life also impact auditor work, with self-efficacy as a mediating factor. Utilizing computer-assisted audit techniques (CAATs) and computer self-efficacy (CSE) also positively impacts auditor work processes by highlighting the relevance of technological advancements in contemporary auditing. More extensive literature on communication in auditing highlights the importance of effective communication in internal audit processes and how it affects organizational results (Handayani et al. 2020). Thus, research studies like this one indicate that improving auditor efficiency through targeted training in communication and other relevant areas can significantly enhance audit quality and overall work performance.

H2:

Communication skills have a positive effect on auditor’s self-efficacy.

Another crucial skill that every forensic expert should possess is psychosocial skills (PSS). This training significantly increases the ability to understand human nature, human behavior, and motives. It also helps to read body language and detect deception. Forensic experts must establish strong relationships with clients and interested parties to obtain accurate information. They also need to be able to work together with other professionals who are qualified for the research, as demonstrated by Boyle et al. (2017). A strong PSS is not just a skill but a crucial tool for auditors to improve their ability to detect and minimize fraud. This skill allows auditors to communicate effectively, establish connections with clients and other stakeholders, and identify warning signs that could indicate fraudulent activity. Investing in strong PSS and other essential skills like TAS (Technical and Analytical Skills) can increase auditors’ ability to detect fraud successfully and, eventually, their internal efficiency, thereby instilling confidence and security in the auditing profession. PSS maintains a rigorous approach to improving auditor efficiency, significantly impacting audit quality and workflow.

The effectiveness of the individual, or their ability to accomplish tasks with success, is a crucial factor in the auditing profession. The Auditor Self-Efficacy (ASE) scale, designed to measure auditor confidence in core competencies such as technical proficiency, technological adaptation, and interpersonal communication, emphasizes the importance of psychosocial competence in auditing (Bowering et al. 2020). Research indicates that emotional intelligence positively affects audit quality, which enhances the auditor’s ability to communicate with clients and manage their emotions effectively. Psychological factors such as self-worth, trustworthiness, and spirituality can affect auditor efficiency, emphasizing the importance of social cognition in audit work (Lari Dashtbayaz et al. 2022). During the COVID-19 pandemic, auditor efficacy was strengthened through face-to-face interviews, verbal and social interactions, vicariate interviews, and virtual audits. This demonstrates auditors’ ability to adjust to crisis psychosocial stressors. Practical communication skills are essential for auditors because they facilitate a more leisurely audit process and help clients develop pleasant relationships, which can result in more honest and straightforward interactions. In addition, emotional intelligence and emotional intelligence skills are critical in detecting fraud since they increase the auditor’s trustworthiness and ability to handle complex and stressful situations (Sari and Nugroho 2021). Understanding and experience in auditing, mediated by personal efficacy, are also crucial in enhancing audit performance, particularly in relatively complex tasks (Martini et al. 2012). Weakened by self-efficacy, professional skepticism is essential for auditors to perform critical analysis and gather appropriate skepticism during an audit (Amlayasa and Riasning 2022). Finally, emotional intelligence and social identity, combined with professional judgment and sensitivity, positively impact auditor work and highlight the importance of psychosocial skills in auditing (Dixon et al. 2005). The relationship between psychosocial skills and self-efficacy is essential to auditor effectiveness and efficiency since it enables them to handle complex professional tasks confidently and competently.

H3:

Psychosocial skills have a positive effect on auditor’s self-efficacy.

Auditing and Accounting Skills (AASs) are essential competencies that auditors and accountants must possess to effectively identify risks, ensure compliance, and contribute to the accuracy of financial reporting. AASs encompass both technical knowledge and the ability to apply critical thinking in complex financial environments. Studies have shown that professionals with advanced AASs are more capable of detecting fraudulent activities and ensuring the integrity of financial data. AASs are crucial for auditor effectiveness since they significantly impact their work environment, report writing quality, and ability to identify fraud. Developing the Auditor Self-Efficacy (ASE) scale, a sub-scale for Technical Proficiency, Technological Adaptation, and Interpersonal Communication, emphasizes the importance of these competencies in enhancing auditor efficacy and self-confidence (Al Natour et al. 2023). The research conducted in Mesir indicates that effective communication, psychosocial, and silent auditing improve the auditor’s efficiency and ability to detect fraud. Computer-assisted audit techniques (CAATTs) strengthen this bond and increase the auditor’s ability to detect fraud (Purnamasari et al. 2022).

According to research conducted in Indonesia, practical communication skills are crucial in helping auditors create accurate audit reports, possibly even more so than professional skepticism and perseverance (Chukwu et al. 2019). The individual’s effectiveness, combined with the auditor’s experience and affected by emotional distress, positively impacts the audit quality and indicates that psychological factors are important in the audit process. This also suggests that virtual audits and emotional disorders significantly impair auditor efficacy (Hammersley 2011).

In the education system, high-achieving students’ audits and accountants with a high degree of personal effectiveness indicate higher levels of stress and anxiety in the classroom, indicating that personal effectiveness is crucial for professional development. Orientation goals also affect self-efficacy, performance appraisal and self-efficacy have a positive impact, and avoidance goals have a negative effect (Salehi and Dastanpoor 2021). In the public sector, professional and personal efficacy are indicators of internal audit quality, while professional efficacy moderates the relationship between audit quality and personal efficacy (Fouziah et al. 2022). In the end, in small-scale audit firms, efficiency is achieved by balancing the objectives and auditors’ attention to detail to detect fraud. This highlights the importance of this approach in complex tasks and the necessity of professional and organizational alignment to reduce audit inspection errors. These studies demonstrate that auditing and accrediting practices are crucial for developing auditor efficacy, improving the auditor’s productivity, ability to communicate their views, and detection skills in various situations and challenges.

H4:

Accounting and auditing skills have a positive effect on auditor’s self-efficacy.

According to the ACFE (2022), fraud is defined as a kind of discreet negotiation using day-to-day tactics to obtain unfavorable benefits or to cause losses for other parties. Fraud can cause significant financial losses and harm an organization’s reputation (Button et al. 2024). The fingerprint detection process (FD) uses data analysis, risk assessment, and investigation methods to identify the fingerprint’s potential (Alkaabi et al. 2019). A strong sense of self-worth and motivation to complete audit tasks are related to high self-efficacy, potentially increasing fraud effectiveness (Dalnial et al. 2014). Research indicates that higher levels of self-efficacy positively correlate with higher fraud employee satisfaction (Amlayasa and Riasning 2022). Consequently, improving efficiency can be a valuable strategy for raising audit quality overall and reducing financial difficulties.

In the context of the Industry 4.0 revolution, the fourth industrial revolution integrates advanced technologies such as AI, robotics, big data, and IoT to automate processes, enhance decision-making, and create interconnected systems. AI optimizes production, IoT enables real-time data analysis, and predictive maintenance reduces downtime. The General Audit System (GAS) aims to improve data anomaly detection performance in the audit process by increasing the frequency of anomalous data compared to manual or physical data collection (Bradford et al. 2020). GAS, also known as Generalized Audit Software (GAS), and Computer-Assisted Audit Tools and Techniques (CAATs) are designed to assist auditors in effectively examining and analyzing data to identify potential fraud, such as anomalous data (Bradford et al. 2020). In a significant way, using GAS improves internal auditor effectiveness by strengthening their ability to identify suspicious material, irregular control, and fraud, hence comprehensively raising the quality of information (Sudirman et al. 2021). According to the Bradford et al. (2020) information system success model, material data are the primary indicators of the quality of information for financial auditors. In contrast, material data are the primary indicators of control and payment irregularities for technical auditors. Integrating analytical data into the methodology for data detection in audits enables auditors to fully understand audit findings and exceptions by utilizing rigorous data collection procedures, which have now become industry standards. Specialized tools like SPSS and CaseWare IDEA and general tools like Microsoft Excel are used for data verification and fingerprint analysis; IDEA is exceptionally user-friendly and does not require a unique label for fingerprint data. CAATs have proven to be a reliable method for detecting fraud, with auditor sentiment significantly indicating its impact on employee productivity and transparency in financial reporting (Hassan et al. 2023). However, issues such as implementation costs, required resources, and database system performance are related to the creation and use of CAATs.

Additionally, developing a flexible approach based on regulations to identify fraud in e-commerce transactions highlights the necessity of meeting various customer needs. Utilizing observational data on a financial and operational basis, as demonstrated by research conducted on public companies in Brazil, increasingly highlights the importance of GAS in identifying problem or issue areas and highlighting areas that require attention. Although GAS offers several benefits for data analysis and fingerprint detection, it is essential to recognize the limitations and ensure that training materials and system quality are sufficient to maximize their usefulness. The evolution of audit methodology and software will be significant in assessing the integrity and observance of the increasingly digital financial transactions in the world.

H5:

Auditor’s self-efficacy has a positive effect on fraud detection.

The use of computer-assisted audit tools and techniques (CAATTs), such as Generalized Audit Software (GAS), has been shown to strengthen the relationship between human efficiency (ASE) and fraud detection

Improving computer literacy—the ability of individuals to use technology to their full potential—contributes to improving literacy, which raises FD’s efficiency. Increased efficiency and accuracy in data analysis by CAATTs help auditors identify fraud more accurately. Increased forensic expertise associated with CAATTs improves auditor efficiency and yields better evidence detection results (Widnyana and Widyawati 2022). However, other elements that affect FD efficacy include workload, professional skepticism, emotional intelligence, and whistleblowing reporting procedures. Self-efficacy substantially affects audit quality and fraud detection when combined with emotional intelligence; however, CAATTs, which offer advanced data analysis tools, attenuate this link. While GAS has numerous advantages, it is crucial to understand its limitations and keep up with professional growth to stay updated with fraud schemes and technical advancements.

Global adoption of GAS still needs to improve. In developed countries like Australia, only 17.4% of internal audit functions traditionally use GAS. In contrast, in developing countries like Nigeria and Tunisia, the adoption of GAS is hindered by issues with day-to-day management, training, and technological compatibility (Esily et al. 2023). Performance expectations and efforts hampered GAS adoption in Malaysia, and it soon needed more social influence (Yusuf et al. 2013). Moreover, GAS is helpful in specific audit contexts, such as Indonesian Syariah audits, and contributes to auditor quality, particularly in large enterprises like the Big Four. According to the DeLone and McLean models, the critical indicator of information quality for financial auditors is detecting suspicious activity, while the focus of technology integrity auditors is on monitoring irregularities in control and expenditure. Good training in GAS usage is essential to increase auditor productivity and usage. However, audit effectiveness is related to GAS, auditor fatigue, and organizational health. Within the educational environment, ease of use and the application of the software hurt students’ performance, even though it does not negatively affect their grades silently (Sheldon and Jenkins 2020).

The relationship between human efficiency and fraud detection is complex and affected by various factors, the most notable of which is the existence of the whistleblower system. When individuals realize their shortcomings and ignorance, their self-efficacy, based on their ability to do tasks and meet goals, is positively correlated with detecting deception. However, a robust reporting system can significantly increase the effectiveness of facial recognition.

H6:

Self efficacy has a positive effect on fraud detection.

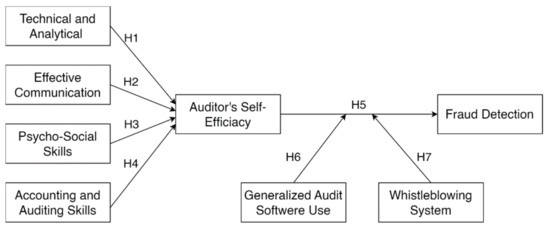

According to research findings, the whistleblowing system provides a safe, structured environment for reporting suspicious activity. It gives individuals the confidence to make decisions based on their judgment without fear of repercussions. This system not only assists employees in reporting non-etis cases but also improves the subject’s sensitivity to fraud detection by providing the necessary shields and barriers (Al Natour et al. 2023). The study also shows that the whistleblower system’s presence significantly affects the fraud detection process, with forensic and investigative audits acting as mediating variables and reducing the subject’s level of efficacy in this process (Halbouni et al. 2016). However, while human efficiency is essential, it sometimes moderates the relationship between whistleblowing and fingerprint detection systems. A few studies indicate that the effectiveness of whistleblowing regulations, subjectivity norms, and the control of public opinion do not significantly influence whistleblowing. In addition, the effectiveness of the whistleblowing system in detecting theft is also affected by organizational barriers, employee privacy, and ethical workplace practices, all of which are crucial for enhancing employee efficiency (Nurcahyono et al. 2021). In the relevant industry, such as the food industry, training programs that increase work productivity and self-efficacy have been shown to improve whistleblowing (Prasetiyo et al. 2024). However, a few studies show that a weak and unreliable whistleblowing system, along with subpar ethics, can hinder the process of whistleblowing, indicating the need for a well-designed and reliable whistleblowing mechanism to maximize the benefits of human efficiency in whistleblowing detection (Nurcahyono et al. 2021). Overall, even if human efficiency plays a crucial role in leak detection, its effectiveness is greatly enhanced by a well-designed and user-friendly whistleblowing system. This system provides the necessary work experience to help applicants understand themselves and be honest, improving their communication ability to increase the fraud detection rate effectively. Information about the theoretical framework is presented in Figure 1 as follows.

H7:

The whistleblowing system strengthens the association between self-efficacy and fraud detection.

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework.

4. Methodology

4.1. Survey and Data Collection

This study uses a cross-sectional design to describe the conditions studied. Cross-sectional design is a research method that collects data from participants at one point in time to assess and analyze certain variables or phenomena. This approach is widely used in social sciences and organizational studies to explore relationships between variables without manipulating them (Setia 2016). In this study, a cross-sectional design is applied to describe the conditions under study, such as the relationship between forensic accounting skills, self-efficacy, and fraud detection. This design allows researchers to capture a “picture” of the current conditions of these variables and their interactions in the context of fraud detection practices among external auditors. By focusing on one particular moment, this study aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the existing dynamics without the influence of temporal changes. This study adhered to internationally recognized research ethics standards, ensuring fairness, transparency, and respect for respondents’ rights. Ethical approval was obtained from the university’s research ethics committee prior to data collection. Respondents were provided with clear information about the study’s purpose, benefits, and procedures, and participation was entirely voluntary, with consent obtained electronically. Personal data were not collected, and confidentiality was strictly maintained, with data used solely for academic purposes and stored securely. Respondents had the right to withdraw or skip questions without consequences. Researchers also provided contact information for any queries, ensuring transparency and integrity throughout the study.

Data were collected over a predetermined period to obtain a comprehensive picture of the role of forensic accounting skills in detecting fraud and the moderating effect of using GAS (Generalized Audit Software) and WBS. This study surveyed external auditors to examine their perspectives on fraud detection and the role of forensic accounting. External auditors, who are responsible for evaluating the accuracy and integrity of financial statements, play a critical role in identifying financial irregularities. By focusing on their insights, this study provides a clear understanding of how auditing and forensic accounting practices intersect in fraud detection. External auditors’ responses are invaluable in this context, as they bring unique and professional perspectives on the challenges and methodologies involved in fraud prevention and detection. The questionnaires were completed by external auditors from Indonesian public accounting firms within four months of data collection. The survey instrument was developed based on a review of relevant literature related to forensic accounting skills, self-efficacy, and fraud detection. Prior to distribution, the survey was pilot tested on 30 external auditors to ensure the clarity of the questions and to improve the instrument based on feedback. Content validation was carried out through expert judgment from academics and practitioners in the field of investigative auditing. The reliability of the instrument was measured using Cronbach’s Alpha, with an average value above 0.80, indicating good internal consistency. The survey was conducted online using a survey platform, namely Google Forms, during the period from March to June 2024. The survey link was distributed through the professional network and associations of external auditors in Indonesia, such as IAPI (Indonesian Institute of Public Accountants). This study has obtained the consent of the respondents; if the respondents do not agree, the questionnaire can be ignored. Furthermore, complete information was provided regarding the purpose of the study, and their participation was voluntary with a guarantee of confidentiality of personal data. Of the total 600 external auditors who participated in the survey, we received 537 valid responses, with a response rate of 89.5%. Respondents came from Big Four and non-Big Four KAPs in Indonesia.

4.2. Measurement

The main instrument in this study was a questionnaire designed using the 5-Likert method to measure each variable described in Table 1 as follows:

Table 1.

Measurement of variables.

The following variables and their corresponding proxy measures were selected to provide a comprehensive understanding of the key elements involved in fraud detection and forensic accounting. Forensic Accounting Skills: This variable is measured by evaluating the auditor’s ability to analyze financial data, communicate effectively, deal with pressure, and apply accounting and auditing knowledge to detect and investigate fraud. This proxy is widely used because it captures the key competencies required for forensic accountants to identify fraudulent activity (Chukwu et al. 2019). The multifaceted nature of forensic accounting skills ensures that all important aspects of fraud detection are taken into account.

Auditor Self-Efficacy: This variable is assessed by measuring three aspects: problem-solving ability, understanding of capabilities, confidence, and persistence. This variable was selected based on Bandura’s (1988) self-efficacy theory, which states that individuals with high self-efficacy are more likely to engage in challenging tasks, such as fraud detection, and perform them effectively. The relationship between self-efficacy and audit performance is well documented, making it an appropriate measure for this study.

Use of Common Audit Software (GAS): The use of GAS is measured by considering several factors, including technological, organizational, professional, client, and personal factors. GAS is a key tool in modern audit practice, and its implementation plays a significant role in improving auditors’ efficiency and accuracy in detecting fraud (Widuri et al. 2016). Given the advancement of technology in auditing, GAS serves as an important measure to assess auditors’ capacity to detect fraud. Whistleblowing System (WBS): This variable includes elements such as policies, procedures, safeguards, follow-up, confidentiality, education, and evaluation to ensure the effectiveness of the whistleblowing mechanism. WBS is important because it provides a structured process for reporting suspected fraud, which enhances fraud detection efforts (KNKG 2008). By fostering a safe reporting environment, WBS helps uncover fraud early, making it an important measure for this study. Fraud Detection: This variable measures the ability to identify potential fraud through methods such as data analysis, risk assessment, and investigation. High self-efficacy in auditors is associated with increased confidence and motivation to perform audit tasks, including fraud detection (Alfordy 2022). The chosen proxies reflect the comprehensive nature of fraud detection, which combines technical expertise with motivation and confidence in the auditor.

4.3. Assessment of Partial Least Square Structural Equation Modeling

This study uses a multiple linear regression analysis method with multiple linear moderation models using WarpPLS 8.0 software. Multiple linear moderation models are intended to test and analyze how moderating variables affect the relationship between independent and dependent variables. The model in this study is precisely to determine whether using GAS (Generalized Audit Software) and WBS as moderating variables will help external auditors in Indonesia disclose fraud with their forensic accounting skills. The demographic profile of the respondents, including gender, age, educational background, and professional qualifications, is described in detail in Table 2.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of the respondents.

5. Results

The 573 samples that could be analyzed in this study are described in Descriptive Statistics in Table 3. Next, based on Table 4, which presents the model fit analysis results, the developed model has performed very well in explaining the relationship between research variables.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics.

Table 4.

Results of model fit test.

This model can be relied on to make inferences and predictions with a significant APC value (p < 0.001) and a moderate ARS (0.418), indicating a strong and relevant relationship between the variables in the model. Adjusted R-Squared Mean approaching ARS indicates that the model remains good even though it takes into account the number of variables. Furthermore, the AVIF and AFVIF values below the ideal threshold indicate no severe problems related to multicollinearity between independent variables. Then, the GoF value, which is far above the minimum threshold, and the SPR value, which does not show Simpson’s paradox, confirm the overall model fit. RSCR approaching 1 indicates a solid contribution of independent variables in explaining the variance of the dependent variable. In addition, the SSR and NLBCDR values equal to 1 indicate the absence of a suppressor effect and the direction of causality by the hypothesis.

The analysis results show that respondents generally exhibit a commendable level of competence in various aspects of the auditor profession. The Forensic Accounting Skill variable tested with Technical and Analytical Skills, Effective Communication, Psychosocial Skills, Accounting, and Auditing has a relatively high average value (around 21–22) with a low standard deviation (around 2.5–2.8). This indicates that most respondents feel competent in these areas, although moderate individual variation exists. The auditor self-efficacy variable has the highest average (27.11) with a relatively low standard deviation (1.99), indicating a high confidence level among auditors in their ability to carry out audit tasks. In addition, the Generalized Audit Software Used variable shows a high average value (37.11) and a low standard deviation (2.33), indicating that respondents generally have a high level of familiarity with the use of audit software. In the Whistleblowing System variable, although the average is quite high (29.27), the relatively high standard deviation (2.75) indicates a significant variation in perception regarding the violation reporting system among respondents. In the fraud detection variable, the average value (30.02) indicates that auditors feel pretty competent in detecting fraud. Still, the relatively high standard deviation (2.90) indicates a more significant difference in perception than other variables.

Measurement Model Assessment

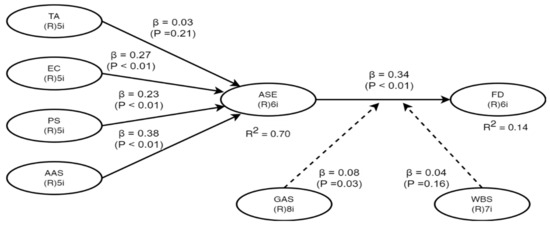

The results SEM modeling research results in Figure 2. of the path analysis in this study examine the relationship between various auditor skills and fraud detection, considering the influence of various factors on the effectiveness of the audit system and fraud detection. The first hypothesis examines the relationship between TA and ASE. The results show a path coefficient of −0.033 with a p value of 0.211, which is greater than 0.05, so this hypothesis is rejected, indicating that technical and analytical skills do not significantly affect auditor self-efficacy. The second hypothesis examines the effect of EC on ASE, with a positive path coefficient of 0.272 and a p value < 0.001, which is smaller than 0.05, so this hypothesis is accepted. This shows that communication skills play an important role in increasing auditor self-efficacy. Furthermore, the third hypothesis, which examines the effect of PS on ASE, produces a positive path coefficient of 0.228 and a p value < 0.001, so this hypothesis is accepted. This shows that psychosocial skills also play a role in increasing auditor confidence in performing audit tasks. The fourth hypothesis tests the effect of AAS on ASE, with a positive path coefficient of 0.382 and a p value < 0.001, indicating a significant and accepted effect, emphasizing that accounting and auditing skills are very important in supporting auditor effectiveness.

Figure 2.

SEM modeling research results.

Regarding the relationship between ASE and FD the fifth hypothesis shows a negative path coefficient of −0.344 with a p value < 0.001, meaning that auditor self-efficacy has a significant effect on fraud detection ability, and this hypothesis is accepted. The next hypothesis tests the effect of GAS (Generalized Audit Software) on FD, producing a negative path coefficient of −0.081 and a p value of 0.025, which is smaller than 0.05, so this hypothesis is accepted. This shows that the use of standardized audit software is related to better fraud detection ability, although the effect is relatively small. Finally, the hypothesis regarding the effect of WBS on FD shows a positive path coefficient of 0.042 and a p value of 0.159, which is greater than 0.05, so this hypothesis is rejected, indicating that the whistleblowing system does not have a significant effect on fraud detection in this context. Overall, the results of this study indicate that communication, psychosocial, and accounting and auditing skills, as well as the use of audit software play an important role in increasing auditor effectiveness and fraud detection, while the whistleblowing reporting system does not show a significant effect on fraud detection.

6. Discussion

In the era of Industry 4.0, skills are very much needed, such as creativity in critical thinking, the ability to adapt, and the ability to face challenging situations. All of these abilities and skills can shape a person’s self-efficacy. Increasing self-efficacy can be accomplished along with growing experience and developing skills in managing thoughts and emotions. All of these abilities and skills can shape a person’s self-efficacy. In auditing, auditor self-efficacy emphasizes the auditor’s belief in their ability to face and solve problems in certain conditions to achieve their desired goals. Auditors who have high self-efficacy do not guarantee that they also have high technical skills. This is because the development of technical skills is obtained through sufficient practical experience rather than confidence in their abilities. Technical skills are mandatory for an auditor, which includes the technical abilities and knowledge needed to conduct an effective and efficient audit. Auditors who have adequate technical skills can help detect fraud. An act of fraud can be motivated by pressure, opportunity, rationalization, and ability, as explained in the fraud diamond theory. The higher the technical skills of an auditor, the faster the fraud can be detected, and the losses caused by the fraud can be minimized. Research has been conducted on the relationship between technical skills and auditor self-efficacy in fraud detection. This study’s results align with research conducted by Al Natour et al. (2023), which stated that technical skills do not significantly affect self-efficacy in fraud detection.

Practical communication skills can be vital to interacting with various stakeholders. An auditor with high communication skills tends to have high self-efficacy due to the ease of communicating and receiving support from various related parties. In addition, an auditor will also have higher confidence in technical skills, technology adaptation, and better interpersonal communication. Communication during the audit process can make it easier for auditors to obtain information on the client’s business processes for audit process planning. In the audit process, an auditor must be able to identify errors that occur in an organization, especially those that lead to fraud. The auditor will use relevant audit procedures during the audit process. Practical communication skills can support the occurrence of fraud because, without this ability, a fraudulent act may not occur. In the fraud diamond theory, capability can be indirectly linked to practical communication skills. Fraud perpetrators must have the ability and skills to effectively ignore internal controls and develop strategies to hide and carry out fraudulent acts. Auditors with high self-efficacy will find it easier to identify fraud in an organization, as this is based on the information they receive from related parties. Fraud is a very detrimental action. Therefore, awareness and vigilance in the organization must be increased to prevent fraud. Research has been conducted on the relationship between practical communication skills and self-efficacy in detecting fraud. This study’s results align with research conducted by Al Natour et al. (2023); Atmadja et al. (2019); and Rustiarini and Sunarsih (2017), stating that practical communication skills are significantly related to auditor self-efficacy in detecting fraud.

Psychosocial skills (PSSs) are vital for forensic accountants and auditors, significantly impacting their ability to detect and prevent fraud. PSSs encompasses a range of abilities, including understanding human behavior, motives, and intentions, reading body language, and detecting deception. These skills are crucial for forensic accountants, who must establish rapport with clients and interviewees to obtain accurate information. Furthermore, PSSs enable them to collaborate effectively with other investigation professionals, as Khadim et al. (2021) highlighted. Thus, PSSs are not just auxiliary skills but essential tools for enhancing an auditor’s fraud detection (FD) ability.

Possessing strong PSSs enables auditors to communicate effectively, build relationships with clients and stakeholders, and identify subtle cues that may indicate fraudulent behavior. These capabilities are crucial for developing trust and obtaining information to uncover fraudulent activities. Research suggests that emotional intelligence (a key component of PSS) positively affects audit quality by enhancing an auditor’s ability to communicate with clients and manage emotions effectively. This is particularly relevant in stressful or high-stakes situations where auditors must maintain professionalism and accuracy.

The relationship between PSSs and auditor self-efficacy (ASE) is critical in auditing. ASE refers to the auditor’s confidence in their core competencies, such as technical proficiency, technological adaptation, and interpersonal communication. The ASE scale emphasizes the importance of psychosocial competence in auditing, highlighting that skills like emotional intelligence, trustworthiness, and effective communication can significantly impact audit quality and workflow. Strong PSSs can also strengthen auditors’ self-efficacy, enabling them to handle complex professional tasks with confidence and competence. For instance, during the COVID-19 pandemic, auditors demonstrated adaptability by conducting face-to-face interviews, virtual audits, and social interactions to manage crisis-related psychosocial stressors.

Moreover, emotional intelligence, social identity, professional judgment, and sensitivity significantly impact auditor effectiveness. Auditors with strong PSSs can perform critical analysis and maintain professional skepticism during audits. This is crucial in identifying and mitigating risks associated with fraud and ensuring a rigorous audit process.

AASs encompass a thorough understanding of accounting principles, auditing procedures, and the ability to apply these standards effectively in forensic investigations. Forensic accountants must identify financial irregularities, analyze financial statements, and use accounting and auditing standards during investigations. The study by Kaur et al. (2023) highlights that AASs are fundamental for detecting fraudulent activities and financial crimes, emphasizing the importance of these skills in forensic accounting.

AAS is essential for detecting fraud and positively impacting the overall quality and effectiveness of financial reporting. According to Al Natour et al. (2023); Handoko et al. (2022); Hassan et al. (2023); Lois et al. (2020); and Rezaee (2005), potent AASs is associated with more accurate and complete financial reporting, which in turn enhances fraud detection (FD) efforts. This relationship is particularly significant given the increasing complexity of financial reporting standards and regulations, which demand high expertise and knowledge from auditors. Navigating these complexities and applying standards accurately is vital for auditors to maintain their professional integrity and effectiveness.

Potent AASs also enhances auditor self-efficacy (ASE), which refers to an auditor’s confidence in their ability to perform their duties effectively. A solid foundation in AAS allows auditors to gain a deeper understanding of a company’s financial operations, thereby increasing their ability to identify potential areas of fraud or misstatement. This confidence translates into better performance and more effective audits. Research indicates that ASE can be enhanced through competencies in technical proficiency, technological adaptation, and interpersonal communication, which are crucial components of AAS (ASE scale). Effective communication, psychosocial skills, and advanced tools like computer-assisted audit techniques (CAATTs) further improve auditor efficiency and fraud detection capabilities (research in Indonesia).

Both technical skills and psychological factors influence the development of ASE. For example, research conducted in Indonesia found that practical communication skills can be more critical for creating accurate audit reports than professional skepticism and perseverance. The individual’s effectiveness, combined with experience, impacts audit quality and highlights the role of psychological factors such as emotional intelligence in the audit process. During the COVID-19 pandemic, auditors with high emotional intelligence were better able to produce higher-quality work, especially when skilled in high-risk auditing techniques. However, virtual audits and emotional disorders posed significant challenges to auditor efficacy, underscoring the importance of technical and psychological preparedness in times of crisis.

In educational settings, high-achieving students in auditing and accounting programs have shown that personal effectiveness is essential for professional development. However, high levels of stress and anxiety indicate that personal efficacy plays a crucial role in managing complex and demanding environments. Similarly, in the public sector, professional and personal efficacy are critical indicators of internal audit quality. Professional efficacy moderates the relationship between audit quality and personal efficacy, suggesting that a balance between technical skills and psychological resilience is necessary for effective auditing practices.

Moreover, in small-scale audit firms, efficiency is often achieved by balancing objectives and paying attention to detail to detect fraud. This approach highlights the importance of aligning professional and organizational goals to reduce errors in audit inspections. The alignment ensures auditors can handle complex tasks and challenges effectively, reinforcing the need for a holistic approach that integrates AAS with psychosocial competencies and professional skepticism.

An auditor’s self-efficacy is the foundation for detecting fraud in the industrial era 4.0. This industry faces various fraud schemes, such as fraud in information technology, artificial intelligence, and big data. Technology was created initially to simplify work; on the other hand, industry players also take advantage of the development of this technology to commit fraud with its sophistication so that it is difficult to detect (Rawat et al. 2023). Amid a massive ocean of data, auditors are required to be able to identify anomalies that indicate fraud. Auditors with high self-efficacy tend to be more proactive, persistent, accurate, and innovative in detecting fraud schemes that are developing very rapidly. High self-efficacy makes auditors more selective in identifying and managing the risks of fraud that occur in today’s industry. A positive reinforcement cycle occurs when auditors with high self-efficacy successfully detect fraud and are motivated to continue improving their performance quality (Khairi et al. 2020; Muterera 2024; Prasasti and Sari 2024; Amlayasa and Riasning 2022). To improve auditor self-efficacy, organizations play a role in allocating adequate resources with training and professional development. In addition, it is essential to create a conducive work environment by providing trust for auditors in carrying out their duties. Close collaboration between auditors and information technology experts is also necessary in overcoming the challenges of fraud in the digital era (Feliciano and Quick 2022). By leveraging each other’s expertise, organizations can improve fraud detection capabilities, strengthen oversight capabilities, and impact the reputation of the organization and the auditors themselves.

Generalized Audit Software (GAS) catalyzes improving auditor self-efficacy. GAS helps auditors concentrate on strategic elements in a systematic audit process to identify fraud risks and evaluate (Tragouda et al. 2024). The output of GAS is used as a basis for assessing fraud risks and formulating effective audit procedures. Auditors with high levels of self-efficacy utilize the advanced features provided by GAS to detect complex fraud by conducting in-depth analysis. Using standardized GAS features makes it easier for auditors to prioritize critical analysis of audit results.

GAS’s statistical analysis and data mining capabilities play an essential role in identifying anomalous patterns and fraud events at a high level of accuracy (Bhat et al. 2022; Mniai et al. 2023; Singh et al. 2024). Consistent use of GAS will encourage the development of technical capabilities and features that support the auditor’s work effectively. Using GAS to carry out auditor duties increases time efficiency and focuses on comprehensive analysis. GAS implements consistent and standardized audit procedures, expanding auditors’ confidence in their duties.

The whistleblowing system is designed as a channel for employees or external parties to report suspected violations or unethical actions within the organization (Achyarsyah 2022). Although this system has great potential to encourage transparency and accountability, it does not directly moderate the relationship between auditor self-efficacy and fraud detection. The whistleblowing system focuses more on reporting mechanisms and whistleblower protection (Meitasir et al. 2022) rather than improving an individual’s ability to detect fraud. Meanwhile, auditor self-efficacy is more related to an individual’s confidence in carrying out their duties, including detecting fraud.

The whistleblowing system is unable to moderate the relationship between self-efficacy and fraud detection because this system acts as a mechanism to confirm suspected fraud that has occurred. The whistleblowing system is reactive and only functions after a party reports it. The success of this system is highly dependent on the awareness and courage of individuals to report. If employees fear retaliation or do not trust the system, they refuse to report. The time it takes to investigate reports of violations is quite long, allowing perpetrators of fraud to cover their tracks or repeat their actions. The hypothesis summary is presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Hypothesis summary.

7. Conclusions

This paper highlights the role of enhancing auditor self-efficacy in detecting fraud. In addition, this study further enhances the understanding of the potential benefits of using technological advancements in the audit process. The whistleblowing system cannot moderate the relationship between accounting and audit skills and auditor self-efficacy or its role in enhancing fraud detection. This paper provides insights for accounting professionals and regulatory bodies in Indonesia, highlighting the importance of leveraging forensic accounting skills and using Generalized Audit Software (GAS) to enhance fraud detection efforts. Forensic accounting skills play a nuanced role in fraud detection, particularly in the Indonesian context. While forensic accounting itself does not significantly impact fraud detection, as evidenced by the limited involvement of forensic accountants in such efforts, the integration of investigative audit capabilities and auditor experience significantly enhances fraud detection outcomes. Additionally, the competence and independence of auditors, bolstered by professional skepticism, are critical factors that enhance the auditor’s ability to detect fraud. However, the moderating effect of professional skepticism does not extend to the whistleblowing system’s impact on fraud detection. Good governance and a robust whistleblowing system raise fraud awareness, although this awareness alone does not directly translate into fraud prevention. Generalized Audit Software (GAS) could further enhance these efforts by providing auditors with advanced tools to analyze large datasets and identify anomalies indicative of fraud. While the specific impact of GAS is not directly addressed in the provided contexts, its potential to improve audit quality and efficiency is well-documented in the broader literature. Moreover, the complexity of related party transactions (RPTs) and their impact on taxable income highlights the need for comprehensive supervision and control, which advanced audit tools and robust whistleblowing mechanisms could facilitate. Overall, integrating forensic accounting skills, investigative audits, and a solid whistleblowing system, potentially augmented by Generalized Audit Software, forms a multifaceted approach to enhancing fraud detection and prevention in Indonesia.

This study shows that forensic accounting skills, auditor self-efficacy, and the application of technology such as Generalized Audit Software (GAS) and whistleblowing systems play a crucial role in fraud detection in the Indonesian financial sector. These findings provide important implications for the accounting and auditing professions, as well as related stakeholders in risk management and fraud prevention. For the accounting profession, the development of forensic accounting skills in the curriculum and ongoing training is essential to improve auditors’ ability to face the challenges of fraud detection. Professional organizations such as IAI and IAPI need to design training that focuses more on fraud detection and the use of modern audit technology. For regulators and public sector stakeholders, the results of this study emphasize the importance of an effective whistleblowing system for fraud prevention. Policies that support fraud detection need to be adjusted to the cultural context and behavior of the organization. Overall, this study provides insights into designing more effective policies in fraud detection and developing professional practices in accounting and auditing, as well as opening up opportunities for further research on the role of technology and auditor psychological skills in improving the integrity of financial statements.

Future research is recommended to use a mixed-methods approach, combining in-depth interviews with external auditors and forensic accounting professionals. In future research, adopting a mixed-methods approach that includes in-depth interviews alongside survey data collection is highly recommended. In-depth interviews offer a unique opportunity to gather richer, more nuanced insights that cannot be captured through quantitative methods alone. Specifically, interviews allow for the exploration of contextual factors such as organizational culture, external pressures, and team dynamics, which may influence an auditor’s ability to detect fraud. Furthermore, interviews can uncover respondents’ motivations, perceptions, and attitudes towards key elements like forensic accounting skills, self-efficacy, and the use of tools such as Generalized Audit Software (GAS) or whistleblowing systems. This will allow for a deeper understanding of the factors that influence fraud detection and the role of forensic accounting in Indonesia. In addition, exploring the perspectives of other stakeholders, such as regulatory bodies or companies’ management, can provide a broader view of the fraud detection landscape. The findings of this study can form the basis for further exploration of the development of effective training programs and policies by professional bodies, such as the Indonesian Institute of Certified Public Accountants (IAPI), which aims to improve fraud detection capabilities among external auditors in the public and private sectors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.A.; methodology, M.A.P.; software, M.A.P.; validation, T.A., M.A.P. and C.-Y.H.; formal analysis, T.A.; investigation, M.A.P.; resources, C.-Y.H.; data curation, M.A.P.; writing—original draft preparation, T.A.; writing—review and editing, I.D.P.; visualization, I.D.P.; supervision, C.-Y.H.; project administration, I.D.P.; funding acquisition, T.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by program World Class Research Universitas Diponegoro 2024. Kementerian Pendidikan, Kebudayaan, Riset dan Teknologi Universitas Diponegoro, Grant number: 357-03/UN7.D2/IV/2024.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Kementerian Pendidikan, Kebudayaan, Riset dan Teknologi, Lembaga Penelitian dan Pengabdian Kepada Masyarakat Universitas Diponegoro, who have supported and assisted the Research Team in the program World Class Research Universitas Diponegoro 2024.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- ACFE. 2022. Occupational Fraud 2022: A Report to the Nations. Austin: Association of Certified Fraud Examiners, pp. 1–96. [Google Scholar]

- Achyarsyah, Padri. 2022. Can Investigative Audit and Whistleblowing Systems Prevent Fraud? Atestasi: Jurnal Ilmiah Akuntansi 5: 124–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albawwat, Ibrahim E., Mohammad E. Al-Hajaia, and Yaser Al Frijat. 2021. The Relationship Between Internal Auditors’ Personality Traits, Internal Audit Effectiveness, and Financial Reporting Quality: Empirical Evidence from Jordan. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business 8: 797–808. [Google Scholar]

- Alfordy, Faisal D. 2022. Effective Detection And Prevention Of Fraud: Perceptions Among Public And Private Sectors Accountants And Auditors In Saudi Arabia. E+M Ekonomie a Management 25: 106–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkaabi, Ahmed Khamis Ali Saeed, Asif Mahbub Karim, Mohammad I. Hossain, and M. Nasiruzzaman. 2019. Assets Digitalization: Exploration of Prospects with Better Control Implementation. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences 9: 960–70. [Google Scholar]

- Al Natour, Abdul R., Hamzah Al-Mawali, Hala Zaidan, and Yasmeen Hany Zaky Said. 2023. The role of forensic accounting skills in fraud detection and the moderating effect of CAATTs application: Evidence from Egypt. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, Eid Mohammed, and Awwad Alnesafi. 2023. Assessing the Impact of Audit Software on Audit Quality: Auditors’ Perceptions. International Journal of Applied Economics, Finance and Accounting 17: 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amlayasa, Anak Agung Bagus, and Ni Putu Riasning. 2022. The Role of Emotional Intelligence in Moderating the Relationship of Self-Efficacy and Professional Skepticism towards the Auditor’s Responsibility in Detecting Fraud. International Journal of Scientific and Management Research 5: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atmadja, Anantawikrama Tungga, Komang Adi Kurniawan Saputra, and Daniel T. H. Manurung. 2019. Proactive Fraud Audit, Whistleblowing and Cultural Implementation of Tri Hita Karana for Fraud Prevention. European Research Studies Journal 22: 201–14. [Google Scholar]

- Azzahroh, Fatimah, Suhendro Suhendro, and Rosa Nikmatul Fajri. 2020. The Effect of Self Efficacy and Fraud Diamond on Fraudulent Behavior Academic Accounting Students. Journal of Business Management and Accounting 2: 322981. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, Albert. 1977. Self-Efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change. Psychological Review 84: 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, Albert. 1988. Self-Efficacy Conception of Anxiety. Anxiety Research 1: 77–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, Mohammad Qazim, Sini Anna Alex, Simran Nanda, and Sevanthi Goutham. 2022. Qualitative Analysis of Anomaly Detection in Time Series. Paper presented at 2022 4th International Conference on Circuits, Control, Communication and Computing (I4C), Bangalore, India, December 21–23; pp. 250–53. [Google Scholar]

- Bowering, Elizabeth, Christine Frigault, and Anthony R. Yue. 2020. Preparing Undergraduate Students for Tomorrow’s Workplace: Core Competency Development Through Experiential Learning Opportunities. Canadian Journal of Career Development 19: 56–68. [Google Scholar]

- Boyle, Douglas M., James F. Boyle, and Brian W. Carpenter. 2017. Accounting Student Academic Dishonesty: What Accounting Faculty and Administrators Believe. Accounting Educators’ Journal 26: 39–61. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, Marianne, Dave Henderson, Ryan J. Baxter, and Patricia Navarro. 2020. Using Generalized Audit Software to Detect Material Misstatements, Control Deficiencies and Fraud: How Financial and IT Auditors Perceive Net Audit Benefits. Managerial Auditing Journal 35: 521–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brody, Richard G., Gaurav Gupta, and Stephen B. Salter. 2020. The influence of emotional intelligence on auditor performance. Accounting and Management Information Systems 19: 543–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Button, Mark, Branislav Hock, David Shepherd, and Paul M. Gilmour. 2024. What Really Works in Preventing Fraud against Organisations and Do Decision-Makers Really Need to Know? Security Journal 37: 965–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukwu, Nkeiruka, T. O. Asaolu, Olubukunola Ranti Uwuigbe, Uwalomwa Uwuigbe, O. E. Umukoro, L. Nassar, and O. Alabi. 2019. The Impact of Basic Forensic Accounting Skills on Financial Reporting Credibility among Listed Firms in Nigeria. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 331: 012041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cilliers, S. 2023. Emotional intelligence as a key driver of the formation of professional scepticism in auditors. South African Journal of Business Management 54: 3654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cressey, Donald R. 1953. Other People’s Money; A Study of the Social Psychology of Embezzlement. Los Angeles: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dalnial, Hawariah, Amrizah Kamaluddin, Zuraidah Mohd Sanusi, and Khairun Syafiza Khairuddin. 2014. Detecting Fraudulent Financial Reporting through Financial Statement Analysis. Journal of Advanced Management Science 2: 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Daraojimba, Chibuike, Kehinde Mobolaji Abioye, Adebowale Daniel Bakare, Noluthando Zamanjomane Mhlongo, Okeoma Onunka, and Donald Obinna Daraojimba. 2023. Technology and Innovation to Growth of Entrepreneurship and Financial Boost: A Decade in Review (2013–2023). International Journal of Management & Entrepreneurship Research 5: 769–92. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, Robert, Gehan A. Mousa, and Anne Woodhead. 2005. The Role of Environmental Initiatives in Encouraging Companies to Engage in Environmental Reporting. European Management Journal 23: 702–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elisha, Ojukwu Sunday, Johnson Johnson Ubi, Kolawole O. Olugbemi, Modupe D. Olugbemi, and Charles C. Emefiele. 2020. Forensic Accounting and Fraud Detection in Nigerian Universities (a Study of Cross River University of Technology). Journal of Accounting and Financial Management 6: 61–72. [Google Scholar]

- Esily, Rehab R., Yuanying Chi, Dalia M. Ibrahiem, Nourhane Houssam, and Yahui Chen. 2023. Modelling Natural Gas, Renewables-Sourced Electricity, and ICT Trade on Economic Growth and Environment: Evidence from Top Natural Gas Producers in Africa. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 30: 57086–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feliciano, Cristiano, and Reiner Quick. 2022. Innovative Information Technology in Auditing: Auditors’ Perceptions of Future Importance and Current Auditor Expertise. Accounting in Europe 19: 311–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouziah, Selvi Novita, Suratno, and Syahril Djaddang. 2022. Fraudulent Financial Statement Detection Based on Hexagen Fraud Theory (Study on Banking Registered in IDX Period 2015–2019). Budapest International Research and Critics Institute-Journal (BIRCI-Journal) 5: 28251–64. [Google Scholar]

- Gaaya, Safa, Nadia Lakhal, and Faten Lakhal. 2017. Does Family Ownership Reduce Corporate Tax Avoidance? The Moderating Effect of Audit Quality. Managerial Auditing Journal 32: 731–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbouni, Sawsan Saadi, Nada Obeid, and Abeer Garbou. 2016. Corporate Governance and Information Technology in Fraud Prevention and Detection: Evidence from the UAE. Managerial Auditing Journal 31: 589–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammersley, Jacqueline S. 2011. A Review and Model of Auditor Judgments in Fraud-Related Planning Tasks. Auditing 30: 101–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handayani, Bestari Dwi, Abdul Rohman, Anis Chariri, and Imang Dapit Pamungkas. 2020. Corporate Financial Performance on Corporate Governance Mechanism and Corporate Value: Evidence from Indonesia. Montenegrin Journal of Economics 16: 161–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handoko, Bambang Leo, Ang Swat Lin Lindawati, and Mazlina Mustapha. 2020. Application of Computer Assisted Audit Techniques in Public Accounting Firm. International Journal of Management 11: 222–29. [Google Scholar]

- Handoko, Bambang Leo, Regine Nathasa Anya Putri, and Sylvia Wijaya. 2022. Analysis of Fraudulent Financial Reporting Based on Fraud Heptagon Model in Transportation and Logistic Industry Listed on IDX during Covid-19 Pandemic. Paper presented at the 2022 6th International Conference on Software and e-Business, Shenzhen, China, December 9–11; pp. 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, Syed Waleed Ul, Samra Kiran, Samina Gul, Ibrahim N. Khatatbeh, and Bibi Zainab. 2023. The Perception of Accountants/Auditors on the Role of Corporate Governance and Information Technology in Fraud Detection and Prevention. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting, ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, Baljinder, Kiran Sood, and Simon Grima. 2023. A Systematic Review on Forensic Accounting and Its Contribution towards Fraud Detection and Prevention. Journal of Financial Regulation and Compliance 31: 60–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadim, Zunaira, Irem Batool, Ahsan Akbar, Petra Poulova, and Minahs Akbar. 2021. Mapping the Moderating Role of Logistics Performance of Logistics Infrastructure on Economic Growth in Developing Countries. Economies 9: 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khairi, Khairil Faizal, Mohamad Subini Abdul Samat, Nur Hidayah Laili, Hisham Sabri, Mohd Yazis Ali Basah, Asmaddy Haris, and Azrul Azlan Iskandar Mirza. 2020. Takaful Protection for Mental Health Illness from the Perspective of Maqasid Shariah. International Journal of Financial Research 11: 168–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komite Nasional Kebijakan Governance. 2008. Pedoman Sistem Pelaporan pelanggaran-spp (Whistleblowing System-WBS). Available online: https://knkg.or.id/ (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Lari Dashtbayaz, Mahmoud, Mahdi Salehi, and Mahdi Hedayatzadeh. 2022. Comparative Analysis of the Relationship between Internal Control Weakness and Different Types of Auditor Opinions in Fraudulent and Non-Fraudulent Firms. Journal of Financial Crime 29: 325–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]