Target2: The Silent Bailout System That Keeps the Euro Afloat

Abstract

Table of Contents

| 1. Introduction........................................................................................................................ | 2 | |

| 2. What is an Optimal Currency Area?............................................................................ | 3 | |

| 3. Some historical examples of unsuccessful and successful OCAs................................. | 4 | |

| 4. Examining the Eurozone as a possible OCA................................................................. | 5 | |

| 5. How has the Eurozone fared since its introduction in 1999?......................................... | 12 | |

| 6. Is the Eurozone an OCA?................................................................................................ | 24 | |

| 7. What is Target2 and how does it work?......................................................................... | 25 | |

| 7.1. What is Target 2?.................................................................................................... | 25 | |

| 7.2. How does Target2 work?........................................................................................ | 25 | |

| 7.3. How has Target2 operated...................................................................................... | 27 | |

| 7.3.1. First phase: 1999–2007.................................................................................. | 27 | |

| 7.3.2. Second phase: 2007–2014.............................................................................. | 27 | |

| 7.3.3. Third phase: 2015–2019............................................................................... | 29 | |

| 7.3.4. Fourth phase: 2020–..................................................................................... | 31 | |

| 8. How Target2 bails out the euro...................................................................................... | 31 | |

| 9. The costs of bailing out the euro.................................................................................... | 35 | |

| 9.1. Private debts are nationalised and monetised...................................................... | 35 | |

| 9.2. Target2 debts are being mutualised across the Eurozone.................................. | 36 | |

| 9.3. Target2 facilitates capital flight and this distorts interest rates in the Eurozone | ||

| ..................................................................................................................................... | 37 | |

| 9.4. Target2 treats sovereign debt as risk-free—the implications for central counterparties | 38 | |

| 9.5. The euro is a structurally incomplete sub-sovereign currency which operates | ||

| with vast amounts of unmanaged financial risk.................................................... | 39 | |

| 9.6. Target2 liabilities are not counted as part of a member state’s national debt and | ||

| the risks associated with them are unmanaged....................................................... | 42 | |

| 9.7. Spillover effects between Eurozone banks and sovereigns—the ‘doom loop’ | 43 | |

| 9.7.1. Two examples of a doom loop................................................................. | 43 | |

| 9.7.2. Breaking the doom loop........................................................................... | 46 | |

| 9.8. Cross-border spillover effects............................................................................ | 48 | |

| 9.9. Spillover effects between Eurozone banks and shadow banks....................... | 52 | |

| 9.10. Cross-border transmission of EZ monetary policy....................................... | 54 | |

| 9.11. Target2 is helping to bail out uncompetitive economies and delay the necessary | ||

| equilibrating adjustments to the real economies of underperforming EZ members | 55 | |

| 10. The Eurozone’s quantitative easing programme and Target2............................... | 57 | |

| 10.1. The ECB’s own capital keys prevented the full implementation of the first | ||

| phase of QE............................................................................................................. | 58 | |

| 10.2. The second phase of QE in response to the COVID-19 pandemic is perpetuating | ||

| a real estate bubble................................................................................................. | 60 | |

| 10.3. The third phase of QE—winding down, except in the case of Italy | 62 | |

| 10.4. The fourth phase of QE—quantitative tightening........................................ | 71 | |

| 10.5. Is the QE programme legal under EU law?.................................................. | 78 | |

| 11. Can a country leave the Eurozone?........................................................................ | 79 | |

| 12. Is there a political solution to the Eurozone problem?......................................... | 81 | |

| 13. Why is the problem with Target2 so Scarcely Known?........................................ | 86 | |

| 14. Implications for the UK.......................................................................................... | 88 | |

| 15. Conclusions............................................................................................................. | 90 | |

| Appendix A. The role of banknotes in Target2............................................................ | 93 | |

| Appendix B. Capital subscription to the European Central Bank, 1 January 2023 | 96 | |

| Appendix C. List of acronyms................................................................................... | 97 | |

| References..................................................................................................................... | 119 |

1. Introduction

- Is the Eurozone an Optimal Currency Area?

- How long can the euro survive if it is not?

- What role does Target2 play in prolonging the euro’s survival?

- Can a political solution save the euro?

2. What Is an Optimal Currency Area?

3. Some Historical Examples of Unsuccessful and Successful OCAs

4. Examining the Eurozone as a Possible OCA

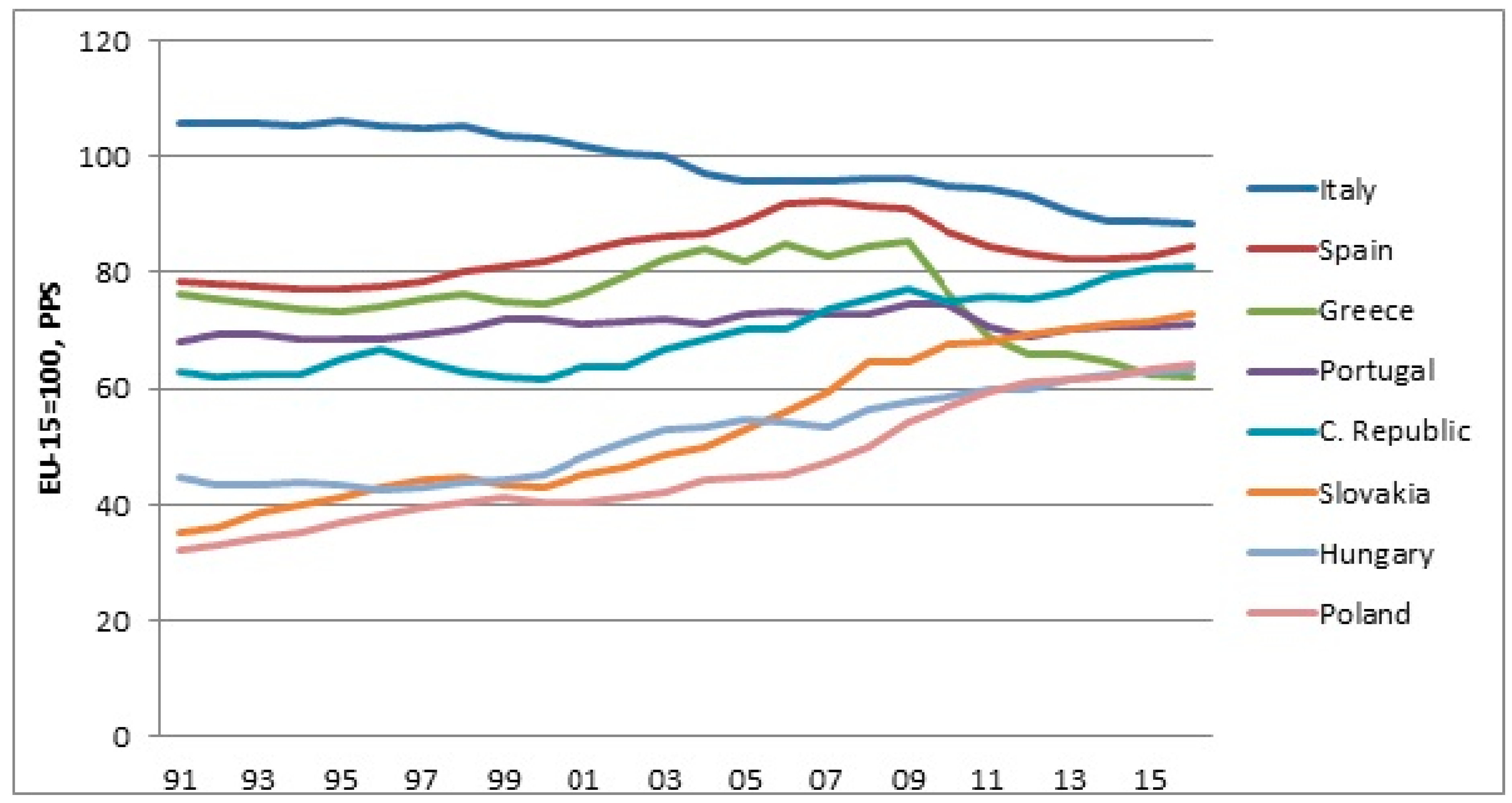

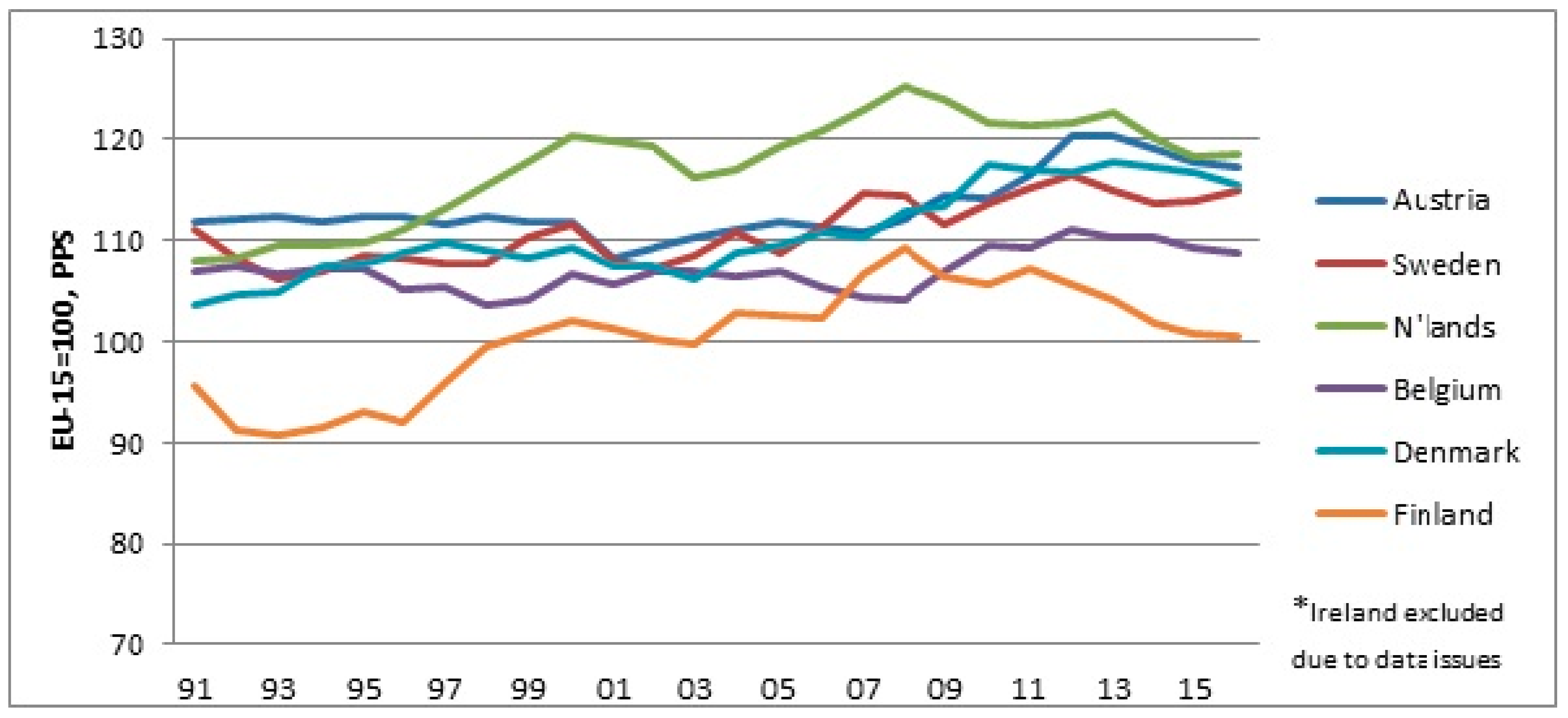

Joining a single European currency dominated by and centred around a strong economic core (focused on Germany) may be beneficial to peripheral member regions in good economic times (such as the boom years of 2000–2007 when capital flowed from the core to the more peripheral parts of Euroland23), but it may prove highly disadvantageous once a major shock like the [Global] Financial Crisis of 2007–200824 occurs, since the scope for independent monetary intervention no longer exists. At the same time, the Eurozone lacks a centralised fiscal stabilisation mechanism by which to provide counter-cyclical intervention.25

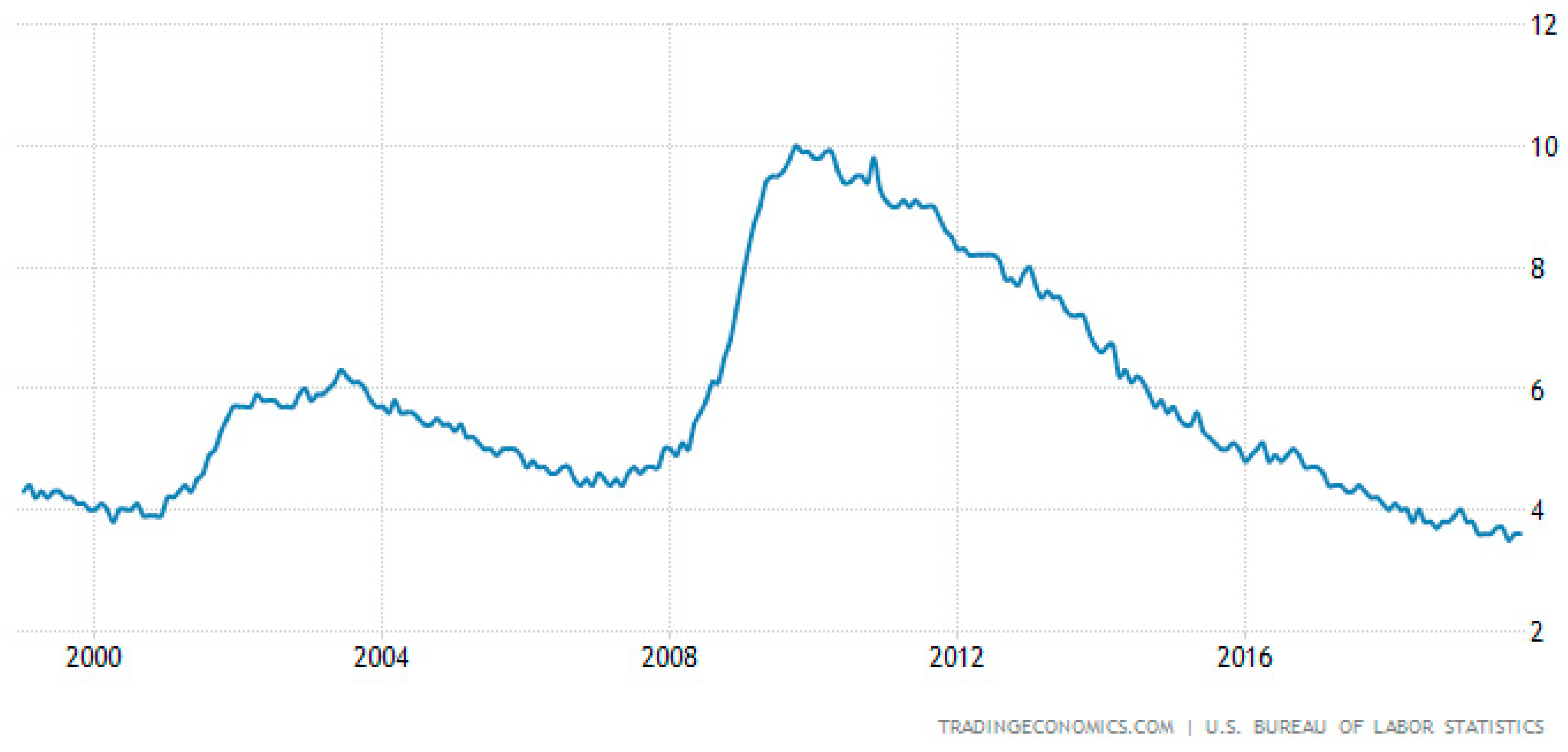

Some of [the OCA] conditions were satisfied at the inception of the EMU, others were missing at the beginning, but improved over time as expected by the endogenous approach to the OCA theory. The common fiscal capacity was the main missing element of the initial construction of the Eurozone, and still is. The common budget is so exiguous that its effectiveness as a shock absorption mechanism is negligible….Some of the concerns raised on the eve of the euro did actually materialise, even if not immediately. First, in its first decade, the Eurozone did not experience major turbulences, because growing financial integration was compensating the need for fiscal transfers, channelling the excess of saving from the ‘core’ to the ‘periphery’. Second, the mechanism generated record-high private indebtedness in the ‘periphery’ and exposure of the banks in the ‘core’, making the whole system more fragile as it relied upon financial market stability. Third, once the long-feared shock [i.e., the GFC] hit, the mechanism proved weak and non-resilient. The inherent weaknesses of the EMU became evident. Fourth, as it had been foreseen, the cost of the adjustment after the shock fell mainly on labour, with much higher and longer unemployment in the Eurozone than both non-Eurozone EU and the US. Fifth, as the [OCA] theory suggested, the lack of common mechanisms of adjustment dramatically increased the socio-economic divergences within the EMU.26

- The European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), which ‘promotes balanced development in the different regions of the EU’.

- The European Social Fund (ESF), which ‘supports employment-related projects throughout Europe and invests in Europe’s human capital—its workers, its young people and all those seeking a job’.

- The Cohesion Fund (CF), which ‘funds transport and environment projects in countries where the gross national income (GNI) per inhabitant is less than 90% of the EU average. In 2014–2020, these [were] Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Greece, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia’.

- The European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD), which ‘focuses on resolving the particular challenges facing EU’s rural areas’.

- The European Maritime and Fisheries Fund (EMFF), which ‘helps fishermen to adopt sustainable fishing practices and coastal communities to diversify their economies, improving quality of life along European coasts’.

- The European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB), which was established to oversee the EU financial system and mitigate systemic risk.

- The three European Supervisory Authorities (ESAs), which were established to provide incentives to avoid excessive risk taking in the financial services industry and to promote a level playing field in support of beneficial financial integration within the EU, namely:

- ○

- The European Banking Authority (EBA);

- ○

- The European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA);

- ○

- The European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA).

- The European Stability Mechanism (ESM),37 which was organised by member states of the EZ to preserve financial stability in Europe by providing financial assistance to EZ states experiencing financial difficulty. The ESM can borrow via bond issuance up to EUR 500 bn, and EUR 190 bn of this was used to bail out the Irish and Portuguese banks in 2010–2011. In September 2012, the ECB introduced a programme of Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT), under which it makes purchases (‘outright transactions’) in the secondary market for bonds issued by EZ members, with the aim of ‘safeguarding an appropriate monetary policy transmission and the singleness of the monetary policy’.38 The total cost of rescuing EU banks between October 2008 and December 2012 amounted to EUR 592 bn in state aid.39

- The Securities Markets Programme (SMP), which was established to ensure depth and liquidity in the malfunctioning segments of bond markets (where transactions were having a significant effect on bond price volatility) and to restore the appropriate functioning of the monetary policy transmission mechanism. To avoid the SMP altering the EZ’s declared monetary policy, the bond purchases conducted through the SMP are sterilised and do not change central bank liquidity.40

- The EBA plans to implement the Basel III banking regulation in a consistent manner across the EU despite Basel III being a voluntary code and estimates made by the OECD that its implementation will reduce global economic growth by between 0.05 and 0.15% p.a.43

- The implementation of the Total Loss Absorbing Capacity (TLAC) rules. The European Commission has plans to increase EU oversight of foreign banks. Foreign banks with significant activities in the EU would be required to operate via ‘intermediate holding companies’. These would have to meet: additional capital requirements; the internationally agreed TLAC rules; and other minimum internationally agreed standards in order to ensure that they could be wound down safely if they fail. The banks would have to issue equity and junior debt (such as contingent convertible (CoCo) bonds), that would be written off in the event of a crisis. Philip Hammond, the UK finance minister at the time, described the proposals as anti-competitive and claimed that they could also ‘constrain prudential authorities in a way that could have an impact on financial stability’.44

- The Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (MiFID) II which deals with the trade and provision of services by investment intermediaries relating to financial instruments (e.g., shares, bonds, units in collective investment schemes, and derivatives). Jeff Sprecher, CEO of Intercontinental Exchange, has described MiFID II—which came into effect in January 2018—as ‘a terrible piece of legislation that imposes tremendous costs on the industry’. MiFID II grew out of the G20 financial regulation principles established in November 200945 to reduce systemic risk following the GFC, but it has been criticised as being excessively complex and its implementation was delayed by a year. One particular issue is the unbundling of investment research and transaction costs.46 MiFID II, in order to achieve full cost transparency for customers, ended the standard industry practice of brokerage firms providing investment research free of charge in return for trade execution business. McKinsey estimated that the profits of European asset managers that pay for research in full could be reduced by 15–20%. Larry Fink, CEO of BlackRock, the world’s biggest fund manager, expressed concern that MiFID II could lead to a dearth of research coverage focused on smaller listed companies.47 Another unintended consequence is the inadequate assessment of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) risks in ESG specialist funds—since ESG assessment requires inputs, like databases and proxy advisors,48 which cannot be valued by MiFID II research valuation approaches—leading to the potential overstatement of ESG integration.49 Brokers and asset managers predicted correctly that MiFID II would lead to fewer trades, reduced price discovery, and less efficient markets.50 Another issue is the reporting of trades to regulators within a specified time, the cost of which has encouraged some hedge funds, such as Brevan Howard and Tudor, to register under the Alternative Investment Fund Managers Directive (AIFMD) rather than under MiFID II.51 The total cost to the finance industry of implementing MiFID II was estimated at more than EUR 2.5 bn.52 Within months of its introduction, trading in a number of futures and options contracts was being shifted from London to the US, and European investment banks were losing business to their US rivals.53 The EU ultimately accepted that the directive was flawed and introduced the MiFID II ‘Quick Fix’ Directive54 in February 2021 with the aim of removing unnecessary administrative burdens on firms before February 2022; these related to product governance, payment for research (enabling the joint payment of execution services and research on small and midcap issuers), client information requirements (such as reporting when a portfolio had decreased by 10% in value), and best execution requirements.

- The Capital Requirements Directive IV (CRD IV). This is damaging for EU financial markets in terms of restrictions on cross-border lending and a bankers’ bonus cap, for example.

- Solvency II. The UK House of Commons Treasury Select Committee launched an inquiry into the ‘manifest shortcomings’ of the Solvency II Directive dealing with the regulation of insurance companies.55 The inquiry’s report was published in October 2017. While the evidence submitted to the committee highlighted problems with the legislation as drafted (e.g., with respect to the risk of procyclicality and market distortion, the calibration of the risk margin, the approval of internal models and subsequent model change, and the volume and complexity of data required from firms), the report was concerned with the way Solvency II has been implemented in the UK by the Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA): ‘An excessively strict interpretation of the requirements of Solvency II, and of its own obligations, has limited the PRA’s thinking in a way which could be detrimental to UK plc’.56 The UK government replaced Solvency II with Solvency UK in November 2022.57 This lowered the ‘risk margin’58 for long-term life insurance business by 65% and for general insurance business by 30%. It also modified the ‘matching adjustment’59 to allow for the inclusion of assets with highly predictable (and not just fixed) cash flows. These changes will enable UK insurers to invest in a broader range of assets, notably those that are more illiquid and have a lower credit rating, but are longer-term and geared towards infrastructure projects.

First, banks should not wait for the perfectly conducive environment for M&A, but rather should work actively with all involved regulators to achieve better synergies in cross-border M&A. They should challenge domestic ring-fencing practices in the Eurozone—in particular, by pushing for cross-border liquidity waivers, which national regulators can grant. Along those lines, banks should push domestic resolution authorities not to add MREL (minimum requirement for own funds and eligible liabilities) requirements to local subsidiaries of banking groups on top of the MREL requirements made by the Single Resolution Board.

Longer-term, European banks need to challenge their core business models. Yes, we have seen various rounds of restructuring and digitisation at all European banks since the Global Financial Crisis. But at their heart, they are set up across traditional client-oriented silos (such as retail or wholesale banks or wealth management divisions), with the majority of their revenue streams reliant on risk intermediation. While rising rates now help these businesses, this is not enough to change the fortune of European banks.

These incremental revenues can create additional ammunition to finance a transition into the future—that is, to venture more deeply into technology, particularly data. Value technology services—such as payment, banking/insurance-as-a-service models or digital assets—are getting earnings multiples of 20 to 30, while connected data services (such as wallet services, connected ecosystem services for mobility, employment, education, commerce, or climate risk data) enjoy multiples of 30 to 40. Traditional risk intermediation businesses, by contrast, have multiples of just 10 to 20.

Transitioning to the future will require more than an innovation lab—companies must undergo sweeping organisational change, turning these platforms into primary or at least equal reporting lines, with future leaders being groomed in these leadership positions.

In the end, it will be up to European banks themselves to reverse the widening gap with US firms. Those that show they can change are likely to find eager support among investors, regulators and prudential authorities across Europe.

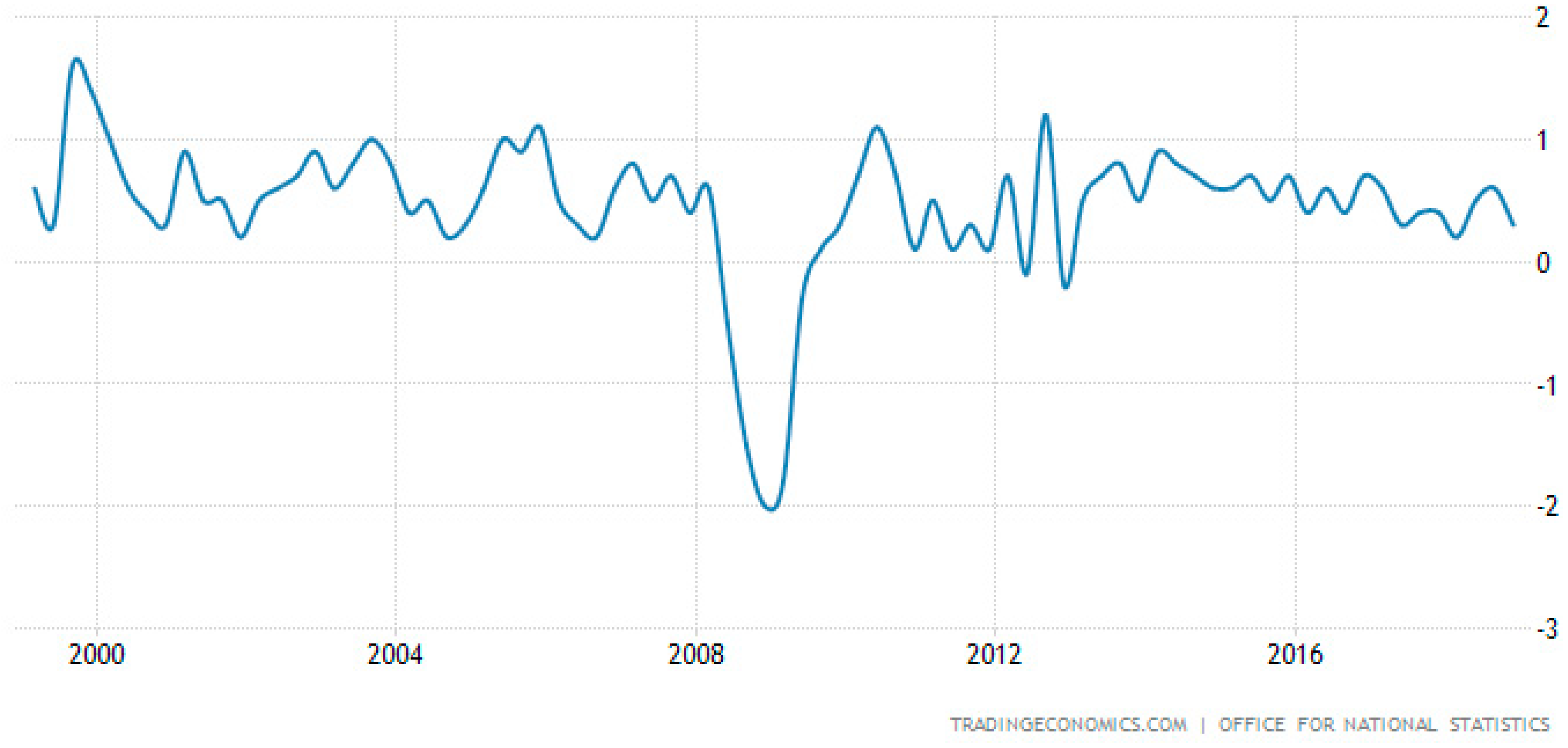

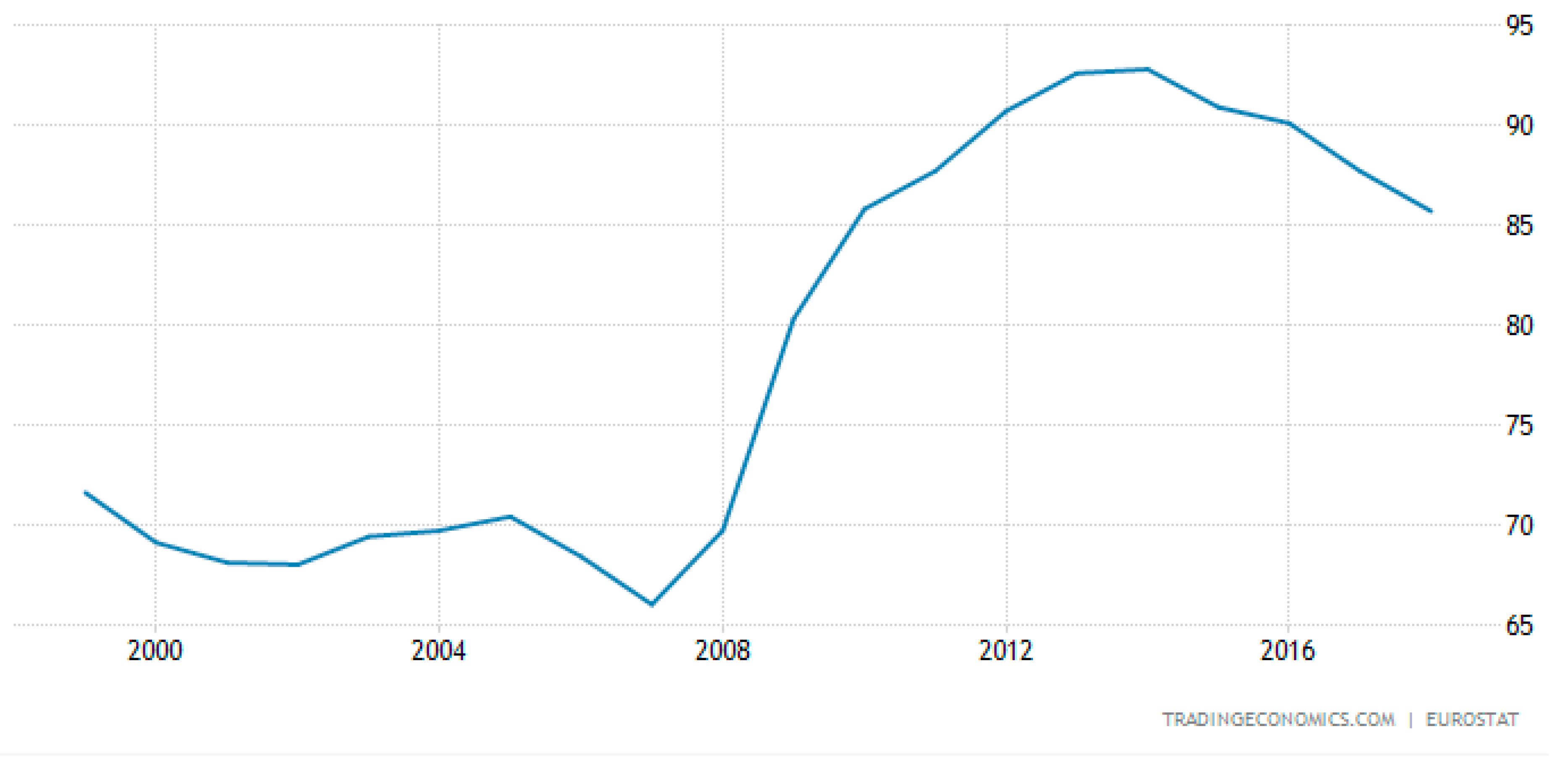

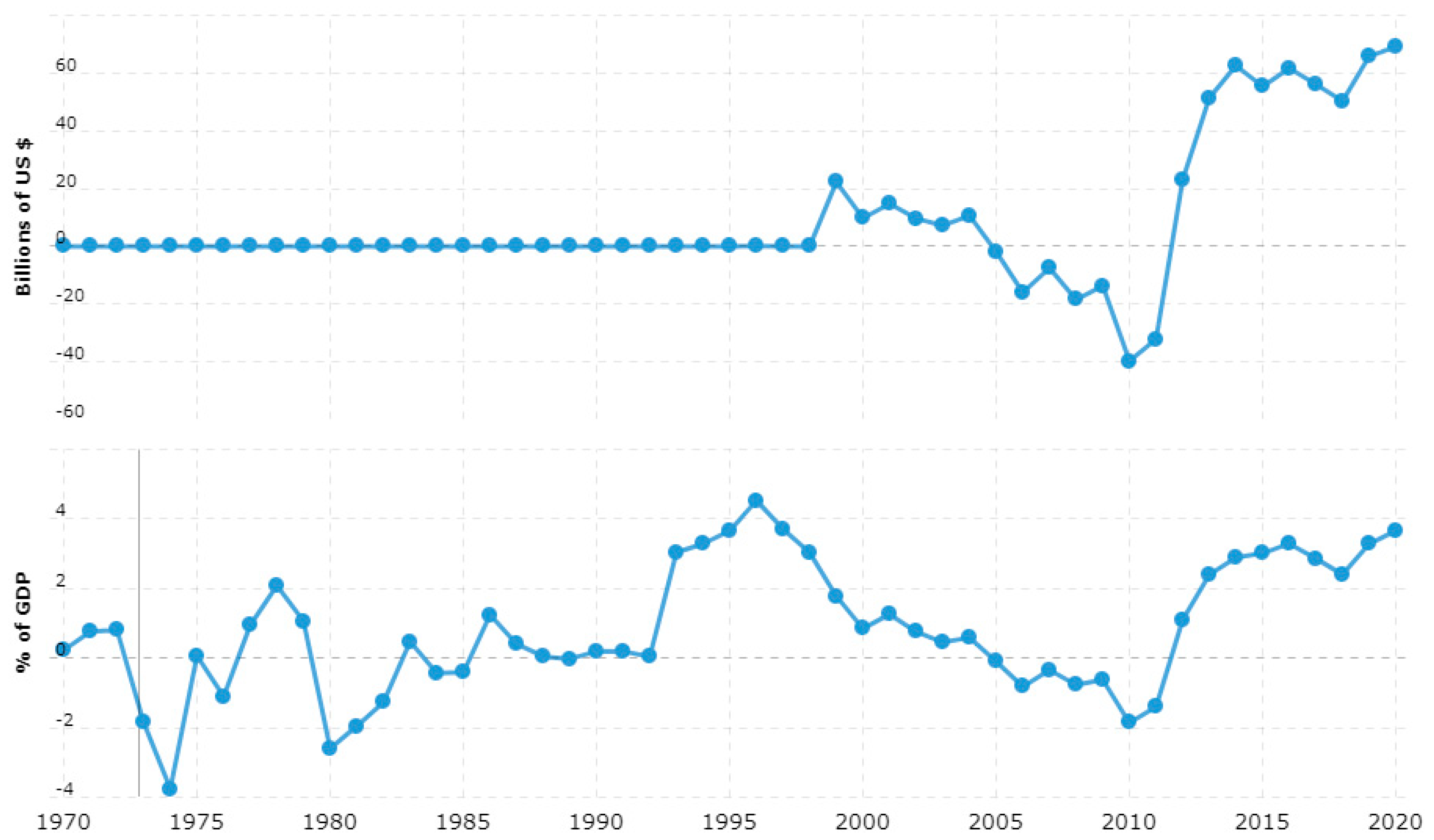

5. How Has the Eurozone Fared since Its Introduction in 1999?

6. Is the Eurozone an OCA?

7. What Is Target2 and How Does It Work?

7.1. What Is Target2?

7.2. How Does Target2 Work?

Italian government bonds held by other Eurozone national central banks and the ECB

+ Target2 liability of Banca d’Italia (owed to the ECB).

Net redemptions of Italian government bonds held by other Eurozone national central banks and the ECB

+ Interest on Italian government bonds held by other Eurozone national central banks and the ECB

+ Net private financial outflows,

Interest on national debt to other Eurozone governments

− Net private financial inflows.

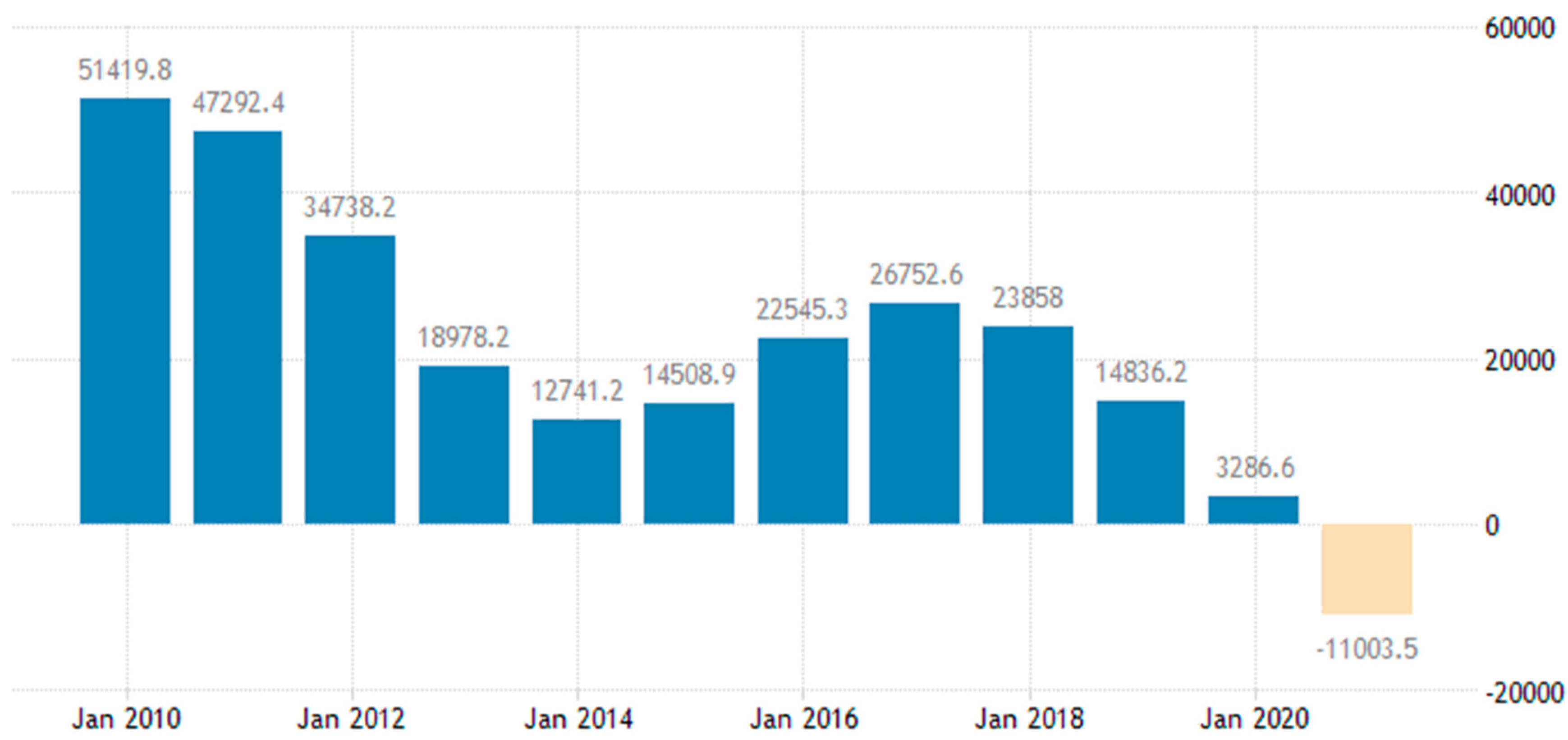

- Before the crisis, both the BoP current account and the trade balance of the countries currently under stress were in deficit, with the exception of Italy where they were approximately balanced;134 these deficits were funded mostly by foreign investments in domestic securities and in the interbank market. The capital flowing in and out of the countries were almost completely netted out, leaving small average net balances in the individual items of the BoP financial account.

- During the crisis, the absolute size of individual items in the BoP increased and its composition changed significantly. The main changes were in the financial account. The reversal of foreign investments in domestic securities and of liabilities issued by domestic MFIs [monetary financial institutions] was not matched by a similar increase in disinvestments of domestic capital previously invested abroad. Net outflows in the financial accounts of the BoP [due to capital flight] were compensated by a considerable increase in the respective NCB’s Target2 liabilities with the ECB.

7.3. How Has Target2 Operated?

7.3.1. First Phase, 1999–2007

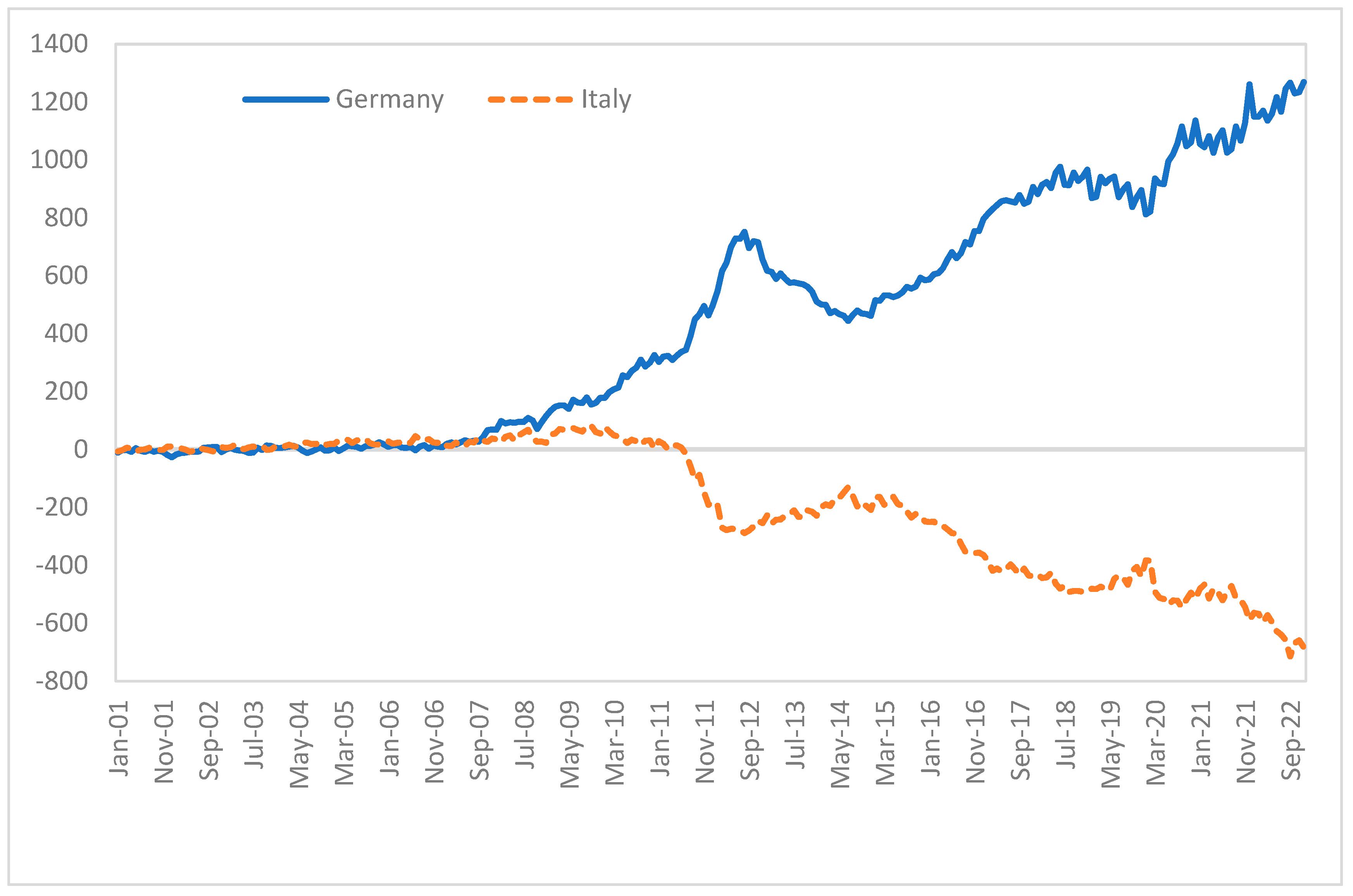

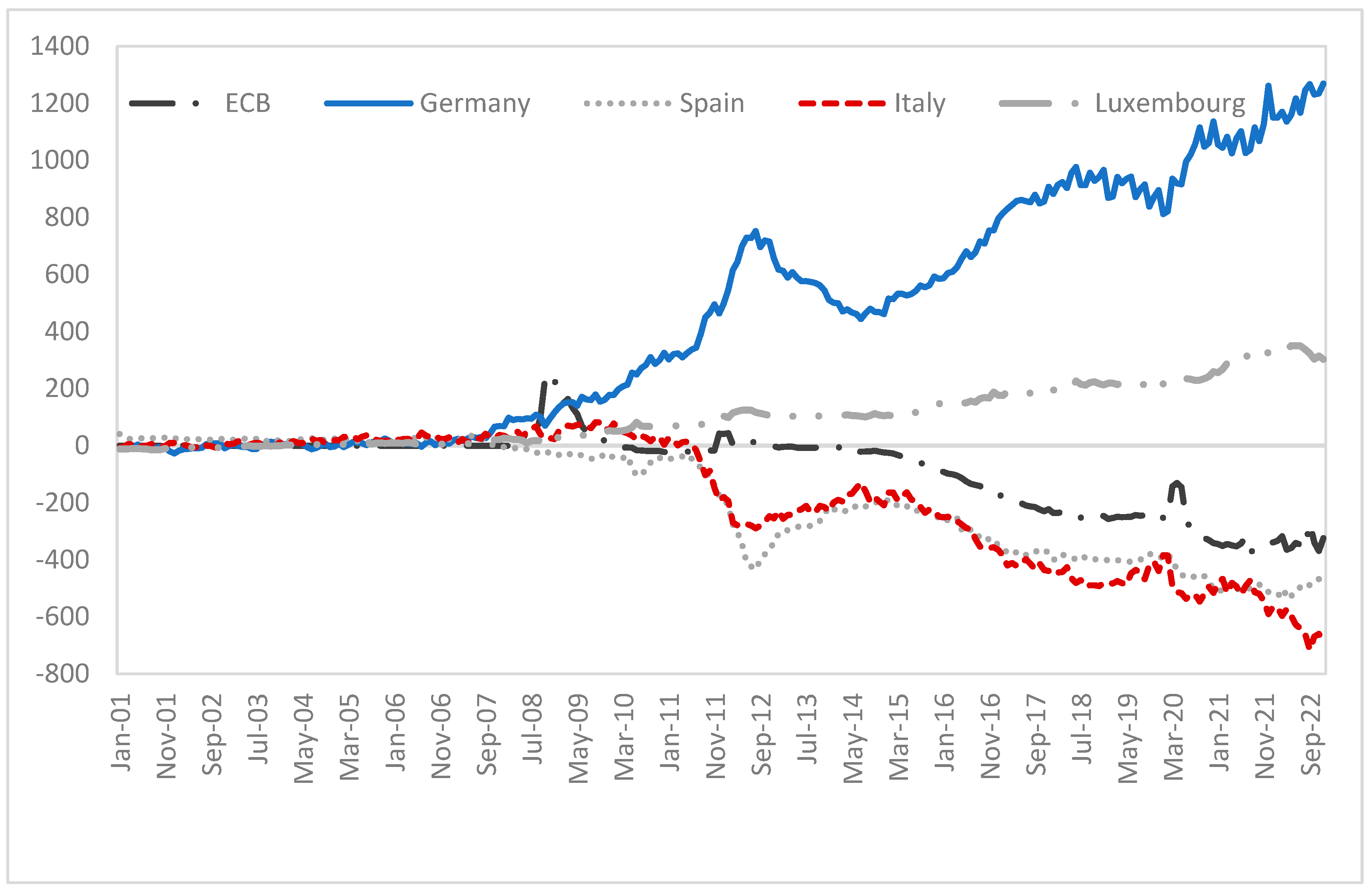

7.3.2. Second Phase, 2007–2014

- The Bank for International Settlements (BIS), the global central bank to the world’s national central banks: ‘Target2 balances grew strongly due to intra-euro area capital flight. At the time, sovereign market strains spiked and redenomination risk142 came to the fore in parts of the euro area. Private capital fled from Ireland, Italy, Greece, Portugal and Spain into markets perceived to be safer, such as Germany, Luxembourg and the Netherlands’ (Auer and Bogdanova 2017, Box A).

- Another BIS study found that ‘Italy is identified as a case of “capital flight” in late 2011’ and that in 2012 ‘Target2 balances reflected something more akin to a currency attack than current account financing or credit reversal’ (Cecchetti et al. 2012, p. 1).

- Banca d’Italia: ‘For all countries, the large increase in Target2 liabilities appears to be mostly related to capital flight, concerning both portfolio investments and cross-border interbank activity’ (Cecioni and Ferrero 2012, p. 22).

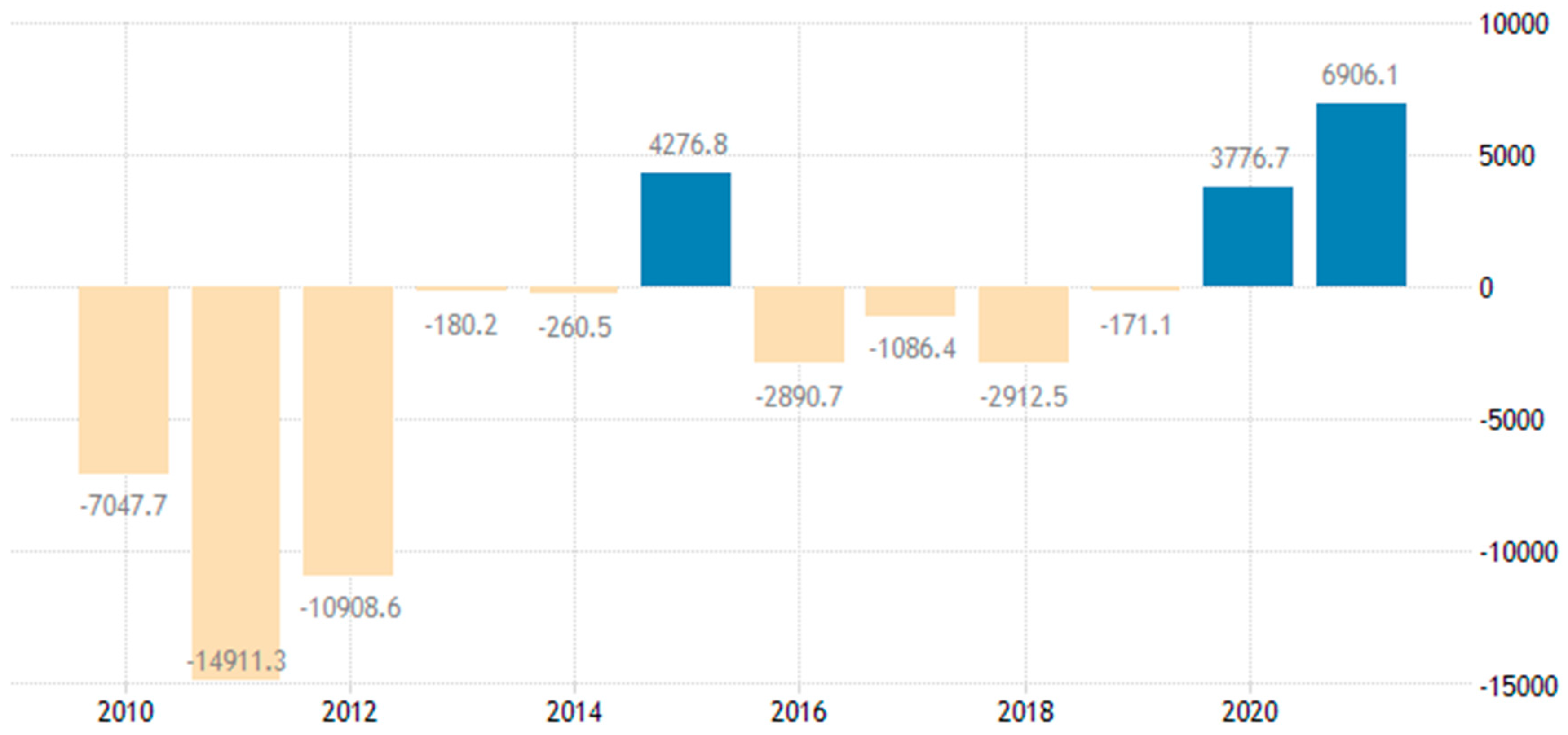

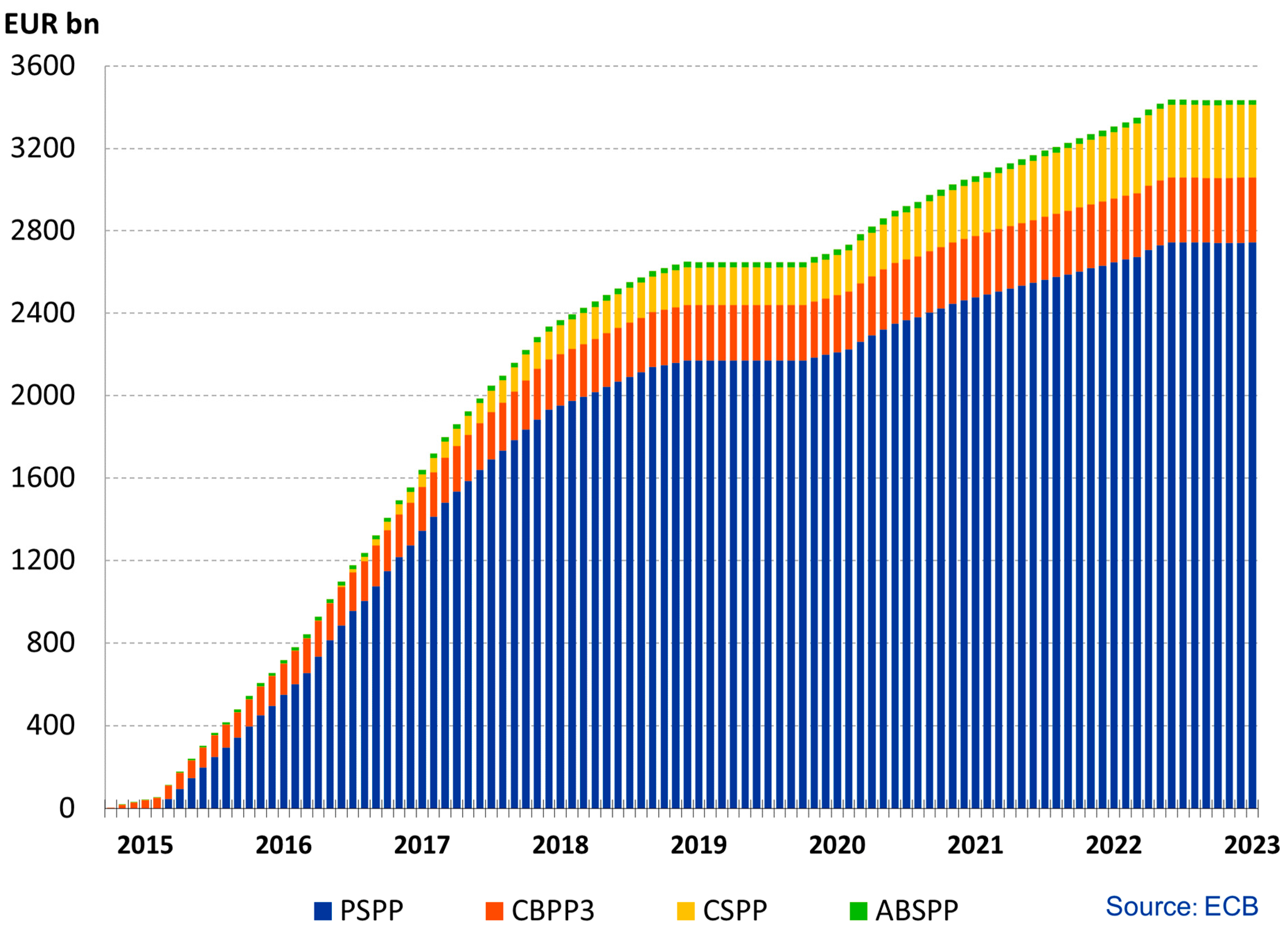

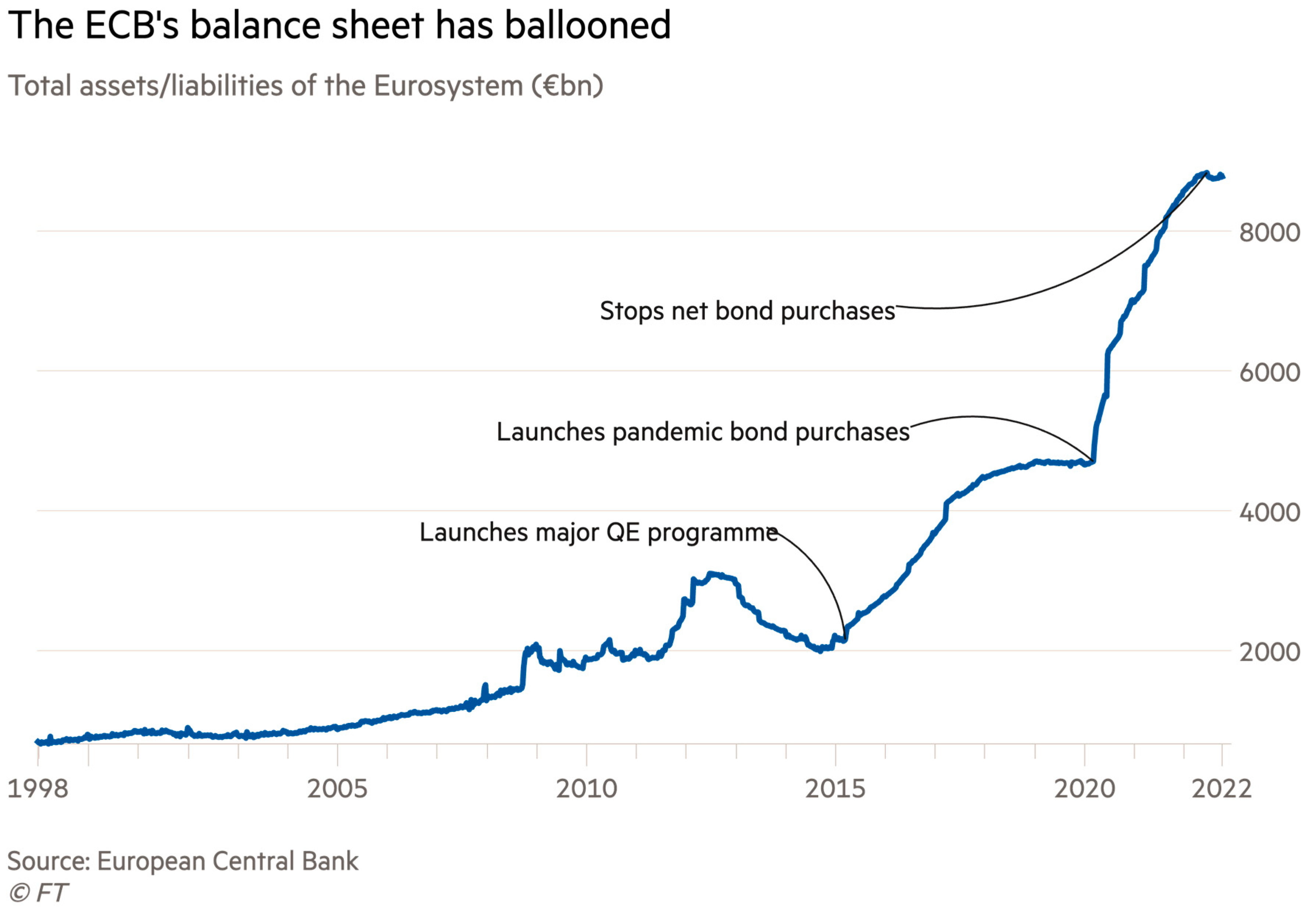

7.3.3. Third Phase, 2015–2019

- The first BIS study cited earlier argues that: ‘record Target2 balances [in 2017] should be viewed as a benign by-product of the decentralised implementation of the asset purchase programme rather than as a sign of renewed capital flight’ (Auer and Bogdanova (2017, Box A)).

- The European Central Bank (2016) argues that ‘mechanical’ effects in the accounting of asset purchases by EZ central banks fully explain the rise in Target2 balances.149 Accordingly, divergence could not be attributable to a ‘capital flight’ from peripheral countries towards northern Europe.

- The ECB’s Financial Stability Review of May 2017 (p. 60) ‘analyses the factors underlying the renewed increases in Target2 balances and concludes that they do not reflect capital flight from certain euro area countries in a context of generalised mistrust of the respective banking sectors’.150

- A Banco de España study asserts that ‘the recent developments do not reflect financial stress or general funding problems in euro area economies, as during the sovereign debt crisis, but are instead mainly linked to the execution of the Eurosystem’s asset purchase programme’ (Alves et al. 2018).

- A study by Banca d’Italia argues that a share of the Target2 movements for Italy occurred because of portfolio rebalancing: ‘Households are turning to insurance companies and professional advisors to invest their savings in mostly foreign assets. This shift does not appear attributable to a preference for financial assets deemed safer (residents actually made net sales of German public sector securities in the period considered), but instead to the pursuit of more balanced portfolios and higher yields than those normally offered on public sector securities. This reflects the difficulty investors face in achieving greater diversification in a domestic financial market characterised by relatively few alternatives to bank bonds and public sector securities’ (Banca d’Italia (c2017) Target2 balances and capital flows).

7.3.4. Fourth Phase, 2020–

8. How Target2 Bails out the Euro

- In a monetary union which is characterised by a single monetary authority, the central bank has to provide deficit countries with the required liquidity to fund the massive capital outflows towards surplus countries. In a system of decentralised central banks, this provision of funds transforms debts between private banks into debts between private banks and their respective central banks, and between central banks of different countries and the ECB. The latter imbalances take place through the Target2 system.

- Central banks in the periphery lend to banks within their jurisdiction against eligible collateral (usually sovereign public debt) to comply with the reserve requirement, and next this central bank money flows to the core, leading to an excess reserve there, which has been used to cancel bank debt within their central banks, and to purchase [the] sovereign public debt of their national treasuries.

- The Eurosystem had no choice but to lend to private banks in the periphery. Otherwise:

- The payment system would have collapsed, because deposits in the periphery could not have been used as means of payments to cancel debts.

- Private banks in the core EZ would have suffered amazing losses given their expos[ure] to banks in the periphery.

- The transmission of monetary policy would have ceased to work: the lack of access to funding would have led banks in the periphery to pay skyrocketing rates for reserves in money and capital markets. All of the whole peripheral economies would have collapsed, dragged by the fall of their banking system. This would have meant the end of the euro.…Sinn and Wollmershäuer have mistakenly pressed several alarm buttons, because they have confused a pegged exchange rate system with a monetary union. In essence, they claim that T2 imbalances are loans granted by the Eurosystem (in the last instance, funded with German savings) which allow peripheral countries to avoid adopting hard measures to restore external equilibrium, and to continue ‘living beyond their means’. Moreover, in the last instance, these loans are a risky asset for Germany. Therefore, their economic policy recommendation is to set a cap on T2 imbalances, and to cancel them by handing over marketable assets. This should force peripheral countries to restore their external balance through a competitive devaluation (falling nominal wages) and fiscal austerity. Accordingly, some countries would find it easier to return to equilibrium leaving the euro.[There are two mistakes with this view, according to Febrero and Uxó]:

- Actually, T2 imbalances are not new loans, but the defensive outcome of a central bank aiming at steering a payment system smoothly, and at granting access to all banks within the monetary union under equal conditions.177 Without refinancing loans, provided by NCBs, private banks in the EZ periphery could not comply with the reserve requirement and the monetary transmission mechanism would not work at all.

- Fiscal austerity and wage deflation would do more harm than good even to Germany, an export-led growth country, because these deflationary measures would shrink its external markets even further. Moreover, austerity-cum-deflation will increase the fraction of non-performing loans in the periphery and, therefore, the likelihood of NCBs capital losses.T2 claims are part of German financial wealth, so the German authors are right when they claim that there is a risk for Germany if there is a disorderly euro breakup. However, their economic policy recommendations are more of a self-fulfilling prophecy than a solution to this risk.

- Without denying that T2 are part of Germany’s financial wealth, Whelan (2012),178 states that in the event of a disorderly euro dissolution, the true problem for Germany, which has followed an export led growth pattern for a long time, would be that its new Deutschemark would appreciate with respect to the already existing euro and, much more, the new currencies (e.g., the Italian lira, the Spanish peseta and so on). … The loss for Germany would be that it could not purchase goods and services in the rest of the EZ without borrowing.

9. The Costs of Bailing out the Euro

9.1. Private Debts Are Nationalised and Monetised

9.2. Target2 Debts Are Being Mutualised across the Eurozone

9.3. Target2 Facilitates Capital Flight, and This Distorts Interest Rates in the Eurozone

9.4. Target2 Treats Sovereign Debt as Risk-Free and the Implications for Central Counterparties

Were that not the case, private sector institutions, such as central counterparties, as well as the central banks holding government debt, would have to take account of the riskiness of different EZ member states’ government debt by way of haircuts and, additionally, in the case of the private sector institutions, by allocating more regulatory capital against it.202 This would make the holding of much of that debt prohibitively expensive, which would, in turn, bring an end to the merry-go-round process of government bonds being issued and ‘sold’ to member state banks with no impact on bank capital.does not grant a general zero risk weight for sovereign debt. However, owing to the analogous adoption of exemptions stated within the Basel II framework, EU regulation de facto grants zero risk weights for the majority of debt issued by EU sovereigns. According to Article 114(4) of the CRR, exposures to member states’ central governments and central banks denominated and funded in the domestic currency of that central government and central bank shall be assigned a risk weight of 0% in the standardised approach. Because of the currency union, the exemption is automatically applicable to all banks within the euro area that finance euro-denominated government debt, leading to preferential treatment of the respective bonds in spite of actual differences in credit risk.201

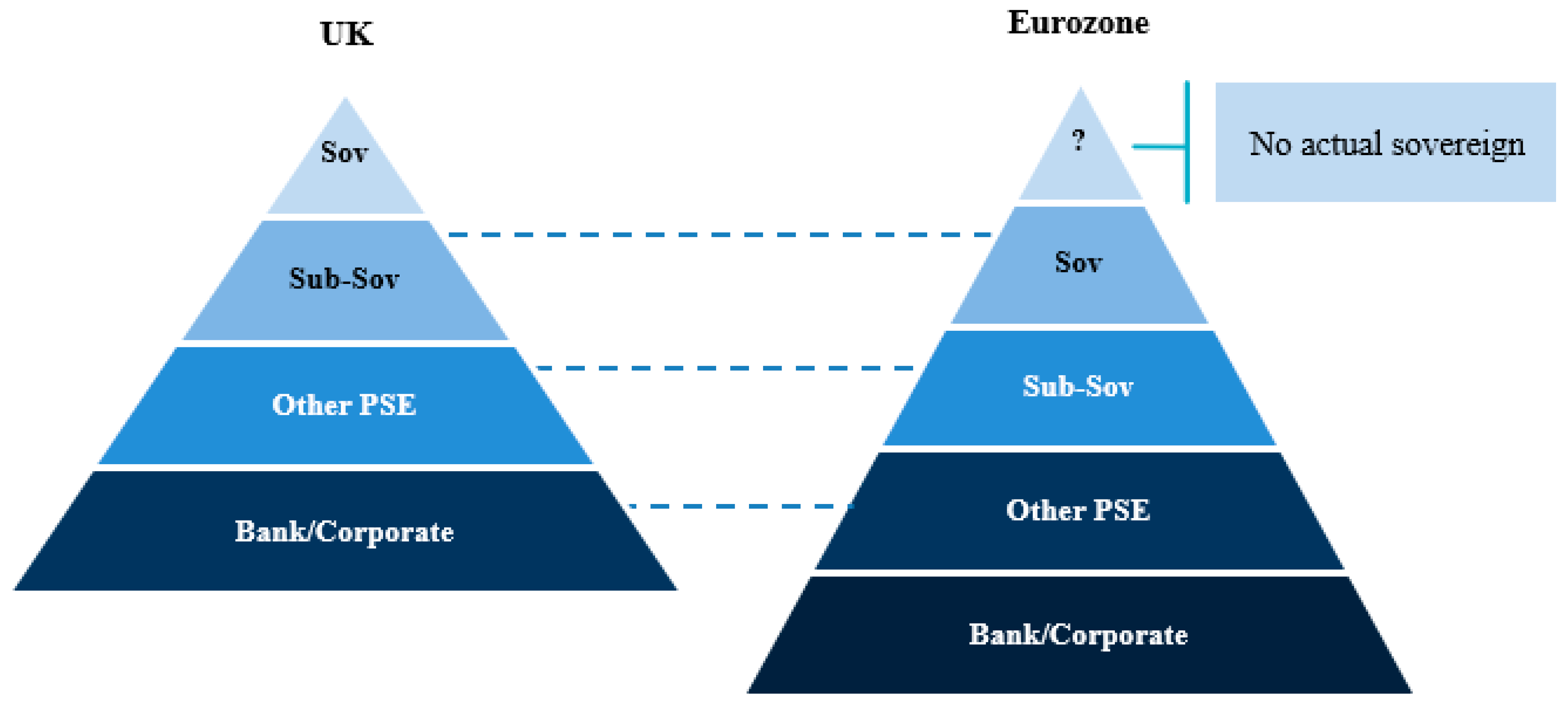

9.5. The Euro Is a Structurally Incomplete Sub-Sovereign Currency That Operates with Vast Amounts of Unmanaged Financial Risk

- No member state individually controls the ECB, so EZ members are ‘sub-sovereign’, implying that the member states do not (and cannot) stand behind their government debts or currency in the way genuine sovereigns do—by printing more money to repay their debts when their tax base proves to be insufficient.207

- There is no joint-and-several liability between member states or lender-of-last-resort facility.208 The EU’s legal structures do not oblige EZ member states to stand together behind each other’s debts in a way that would protect the balance sheets of EZ financial institutions through member states’ collective guarantee and collective control over the ECB. This implies that the following statement made by an Executive Board member of the ECB, while true for a conventional central bank, is not true for the ECB: ‘The only risk-free assets in the euro area are the ECB’s own liabilities’.209 There are no risk-free assets in the EZ.

- There is no EZ-wide bank deposit insurance scheme.

- The EZ’s banks are generally weak and there have been no major cross-border mergers to increase the strength of the banking system.

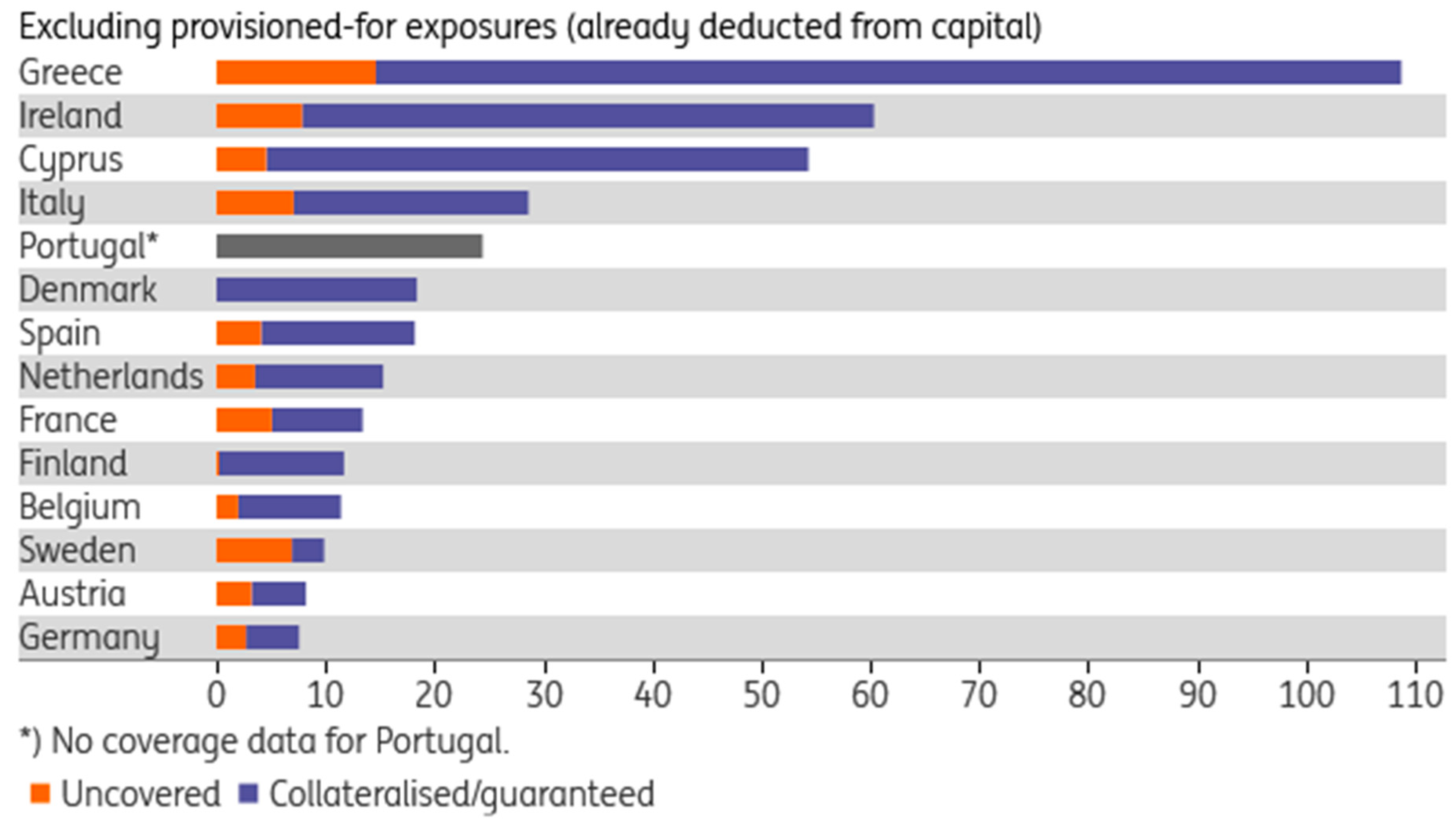

- There is a significant problem with non-performing loans.210

Low aggregate bank profitability in the euro area, which weakens the resilience of the euro area banking sector, is partly explained by the persistent underperformance of a sub-set of banks. These banks all stand out in terms of elevated cost-to-income ratios. But there also appear to be three distinct groups: (i) banks struggling with legacy asset problems; (ii) banks with weak income-generation capacity; and (iii) banks suffering from a combination of cost and revenue-side problems. The common cost inefficiency problem seems most pronounced for the largest and smallest banks. Three strategies, all of which should reduce overcapacity, could address the root causes, while avoiding increasing market power or the systemic footprint of institutions which are already systemically important. For some banks, the focus should be on targeting continued high stocks of non-performing loans (NPLs). But in systems with many weak-performing small banks, consolidation within their domestic system could improve performance. Finally, a combination of bank-level restructuring and cross-border M&A activity could help reduce the costs and diversify the revenues of large banks that are performing poorly.211

- Non-standard NPL treatment. Contrary to normal accounting practice around the world, the rump of NPLs—such as business loans, mortgage lending to consumers, and consumer credit—is discounted and then treated as performing. Treating this rump as performing debt is premised on the borrower achieving partial repayment, despite evidence that the non-rump portion of the debt will not be recovered and despite no adjustment being agreed to the amount owed by the borrower.

- Accounting practices that leverage the sovereign assumption. The EU has permitted banks to securitise NPLs and repackage them, with guarantees given by the relevant EZ member state in which the borrowers are located. It then permits EU banks to hold the resulting securitised NPLs at a level reflecting a sovereign treatment of the EU member state guarantee—see Figure 25 which shows that Greek banks, for example, have government guarantees in respect of NPLs of around 100% of their shareholders’ equity. This has alarming similarities with the repackaging of US sub-prime mortgages into supposedly ‘prime’ segments that sparked the Global Financial Crisis.219 These guarantees should be considered part of each member state’s national debt, but they are not.220

- Opaque accounts. Eurosystem accounts are opaque. They do not list all public debts in the manner adopted by other developed countries, such as the UK or US. The system runs four different sets of accounts, but, when consolidated, it assumes the amounts owing between NCBs and the ECB can be netted, thereby disregarding the intra-system gross exposures. It is unclear whether this assumption is legitimate, even under EU law.

- The fundamental design flaw in the legal architecture underpinning the EZ, which treats both the EZ and its member states as sovereign when these two assumptions are mutually incompatible.

- The extent of existing EZ member state debt that is not jointly-and-severally guaranteed in law—and which is not readily apparent from publicly available accounts.

- The fact that the true situation might be worse than is apparent, given Eurozone accounting practices—and may be worse still given the opacity of such accounting practices.

- The fact that EU and EZ regulators are not in a position to manage significant financial risk effectively, since they are structurally unable to reconcile the need to maintain the viability of the Eurozone with the need to regulate for financial safety and soundness.

9.6. Target2 Liabilities Are Not Counted as Part of a Member State’s National Debt, and the Risks Associated with Them Are Unmanaged

it is not simply a matter of adding the Target2 debt, since, depending upon which account that indebtedness is on, it may need to be collateralised by the borrowing NCB, and it is perfectly possible that the collateral is already counted in the ‘General government gross debt’ of the country of the borrowing NCB. On any such portion, the Target2 debt taken against collateral does not increase the ‘General government gross debt’.

On the other hand, the debt may not be collateralised at all, or else the collateral pledged falls outside the ‘General government gross debt’: in either of those cases, the Target2 debt does increase the overall debt.223

Then there is the question of the excess Target2 debt which is netted away at the end of each business day, and which is not collateralised with bonds that are already included in ‘General government gross debt’. We do not know who exactly are the debtors and creditors for this extra amount, which I believe to be €1.2 trn.224

9.7. Spillover Effects between Eurozone Banks and Sovereigns—The ‘Doom Loop’

9.7.1. Two Examples of a Doom Loop

9.7.2. Breaking the Doom Loop

The first set of ideas relates to: (i) the removal of the internal ratings-based (IRB) approach framework for sovereign exposures; (ii) revised standardised risk weights for sovereign exposures held in both the banking and trading book, including the removal of the national discretion to apply a preferential risk weight for certain sovereign exposures; and (iii) adjustments to the existing credit risk mitigation framework, including the removal of the national discretion to set a zero haircut for certain sovereign repo-style transactions.

The second set of ideas relate to mitigating the potential risks of excessive holdings of sovereign exposures, which, for instance, could take the form of marginal risk weight add-ons that would vary based on the degree of a bank’s concentration to a sovereign (defined as the proportion of sovereign exposures relative to Tier 1 capital).

The third set of ideas is related to the Pillar 2 (supervisory review process) and Pillar 3 (disclosure) treatment of sovereign exposures [in the Basel framework]. Regarding the former, these include ideas related to guidance on: (i) monitoring sovereign risk; (ii) stress testing for sovereign risk; and (iii) supervisory responses to mitigating sovereign risk. Regarding the Pillar 3 framework, this paper includes ideas related to disclosure requirements related to banks’ exposures and risk-weighted assets of different sovereign entities by jurisdictional breakdown, currency breakdown and accounting classification.

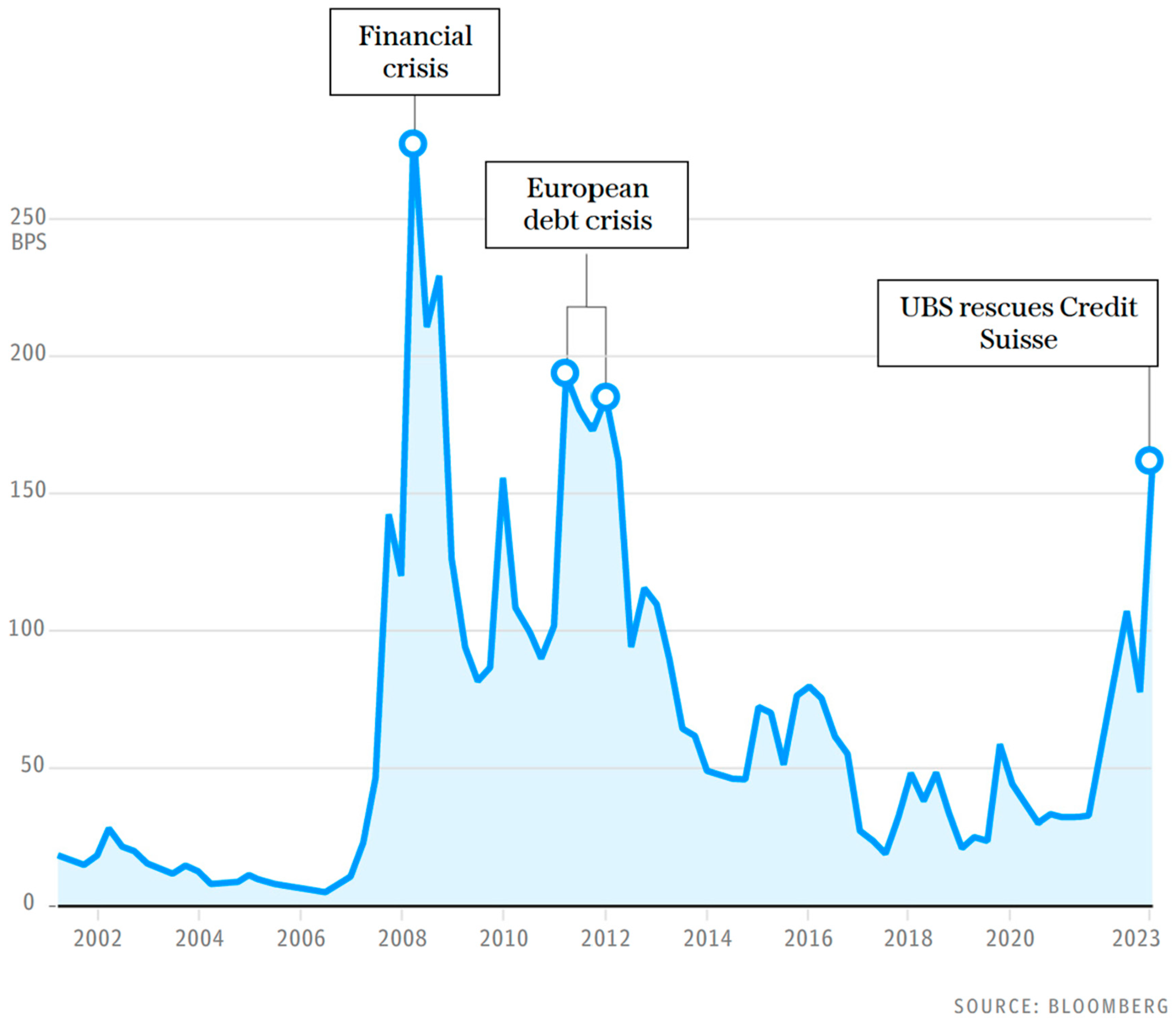

9.8. Cross-Border Spillover Effects

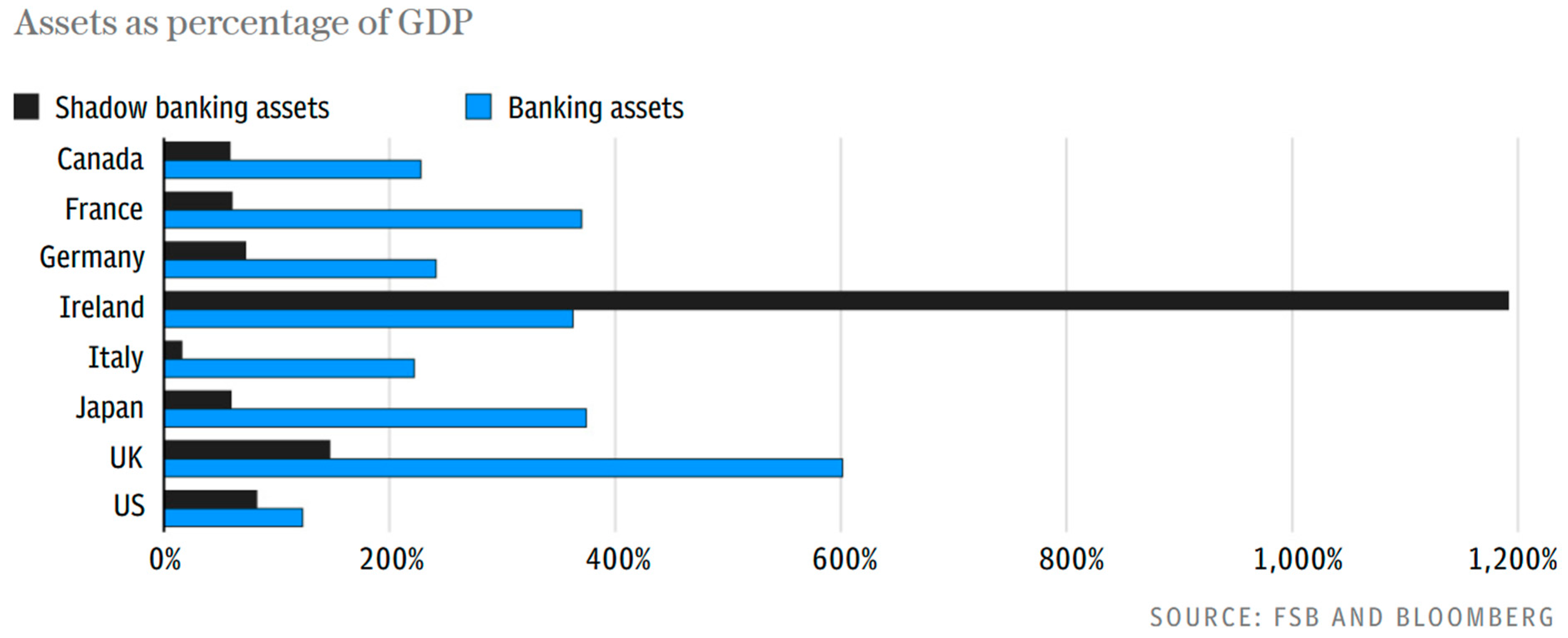

9.9. Spillover Effects between Eurozone Banks and Shadow Banks

9.10. Cross-Border Transmission of Eurozone Monetary Policy

9.11. Target2 Is Helping to Bail out Uncompetitive Economies and Delay the Necessary Equilibrating Adjustments to the Real Economies of Underperforming Eurozone Members

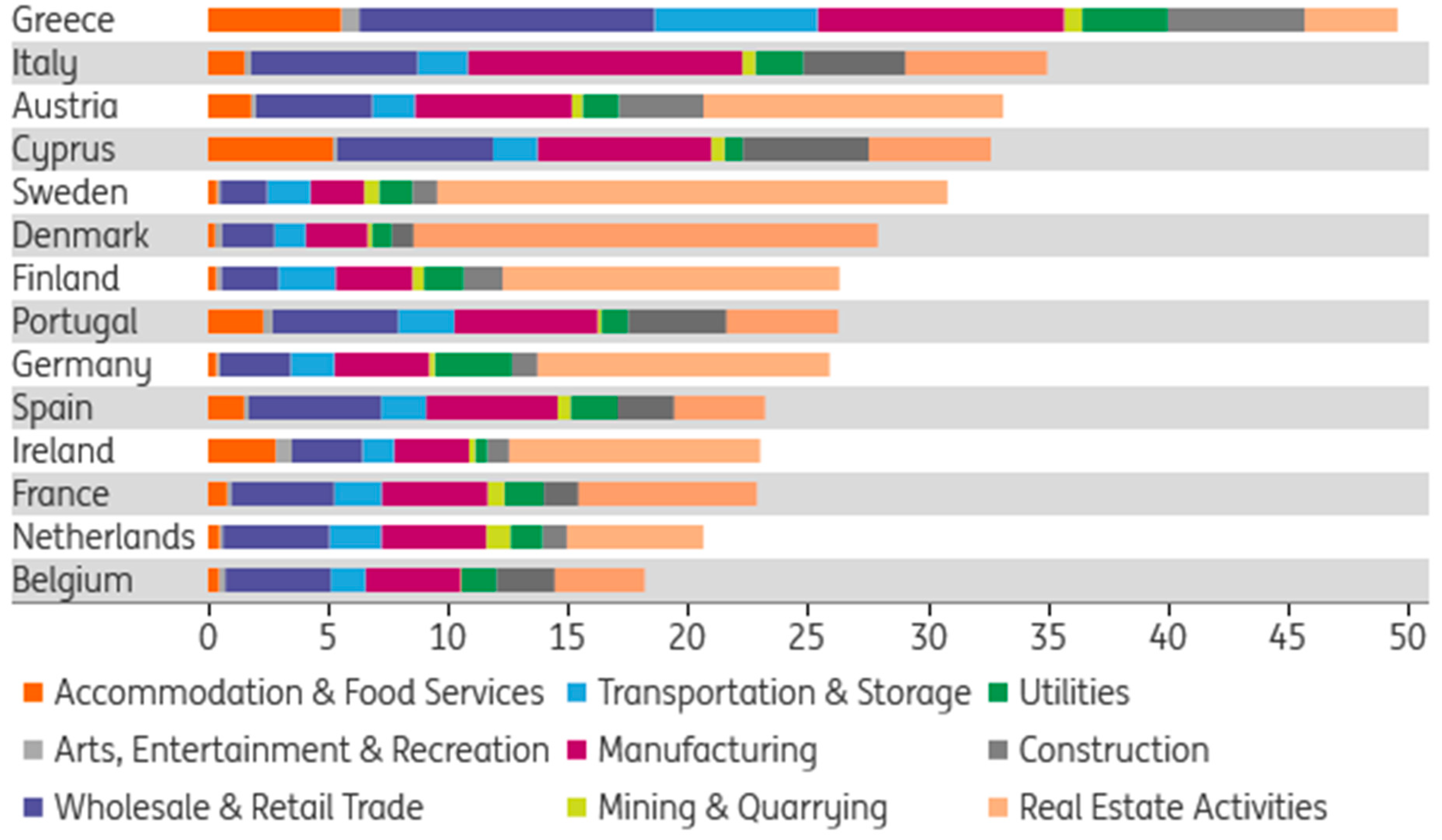

Far from encouraging economic convergence, the monetary integration process has increased the productive, trade, and financial imbalances among the Eurozone’s member countries. The division of labour inside the European Monetary Union was further polarised between core economies, specialising in high value-added goods, and the peripheral ones, specialising in middle-low value-added goods. Furthermore, the adoption of a single currency led to the worsening of external account balances. In this sense, the progressive trade deficits experienced by the peripheral countries were financed by the massive financial funds of the core countries. These imbalances are the key element in the sovereign debt crisis that the peripheral countries are facing today [i.e., in 2017]. The austerity policies applied have placed responsibility on these countries. However, these policies have only worsened the problem. Any attempt to solve this situation should, first, try to correct productive imbalances, keeping in mind that the weight of the adjustment should be shared by both debtor and creditor countries274—which is in line with the Keynes Plan.

One day, the house of cards will collapse. The euro has been betrayed by politics, the experiment went wrong from the beginning and has since degenerated into a fiscal free-for-all that once again masks the festering pathologies. Realistically, it will be a case of muddling through, struggling from one crisis to the next. It is difficult to forecast how long this will continue for, but it cannot go on endlessly…The Stability and Growth Pact has more or less failed. The moral hazard is overwhelming. Market discipline is done away with by ECB interventions. There is no fiscal control mechanism from markets or politics. This has all the elements to bring disaster for monetary union. The no-bailout clause is violated every day and the European Court’s approval for bailout measures is simple-minded and ideological. … The ECB has crossed the Rubicon and is now in an untenable position, trying to reconcile conflicting roles as banking regulator, Troika enforcer in rescue missions and agent of monetary policy. Its own financial integrity is increasingly in jeopardy.

The venture began to go off the rails immediately, though the structural damage was disguised by the financial boom. There was no speed-up of convergence after 1999—rather, the opposite. From day one, quite a number of countries started working in the wrong direction. A string of states let rip with wage rises, brushing aside warnings that this would prove fatal in an irrevocable currency union. During the first eight years, unit labour costs in Portugal rose by 30% versus Germany. In the past, the escudo would have devalued by 30%, and things more or less would be back to where they were. Quite a few countries—including Ireland, Italy and Greece—behaved as though they could still devalue their currencies. The elemental problem is that once a high-debt state has lost 30% in competitiveness within a fixed exchange system, it is almost impossible to claw back the ground in the sort of deflationary world we face today. It has become a trap. The whole Eurozone structure has acquired a contractionary bias. The deflation is now self-fulling. The first Greek rescue in 2010 was little more than a bailout for German and French banks. It would have been far better to eject Greece from the euro as a salutary lesson for all. The Greeks should have been offered generous support, but only after [they] had restored exchange rate viability by returning to the drachma. [The fear was a chain-reaction reaching Spain and Italy, detonating an uncontrollable financial collapse. This nearly happened on two occasions, and remained a risk until Berlin switched tack and agreed to let the ECB shore up the Spanish and Italian debt markets in 2012.]

Cloaking it all is obfuscation, political mendacity and endemic denial. Leaders of the heavily indebted states have misled their voters with soothing bromides, falsely suggesting that some form of fiscal union or debt mutualisation is just around the corner. Yet there is no chance of political union or the creation of an EU treasury in the forseeable future, which would in any case require a sweeping change to the German constitution—an impossible proposition in the current political climate. The European project must therefore function as a union of sovereign states, or fail.276

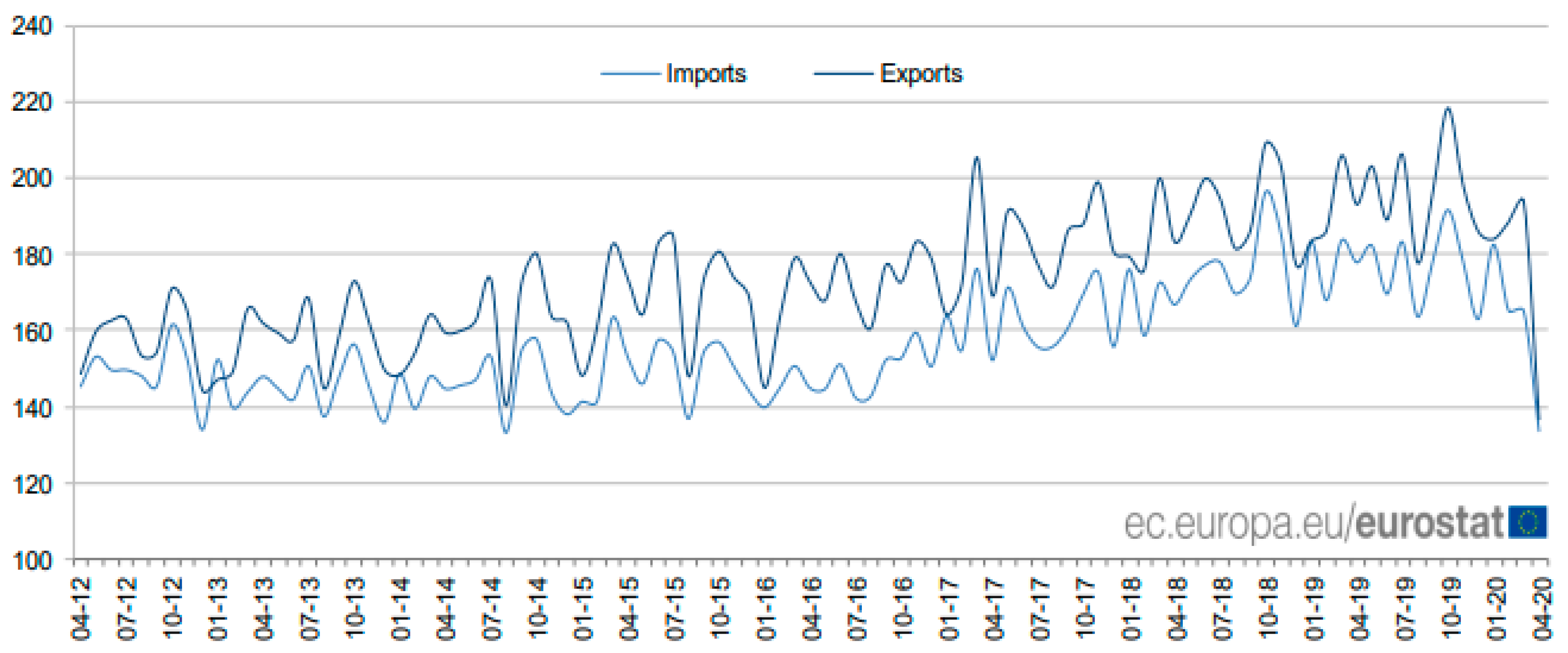

10. The Eurozone’s Quantitative Easing Programme and Its Reversal

10.1. The ECB’s Own Capital Keys Prevented the Full Implementation of the First Phase of QE

because of a shortage of German Bunds. Remember how European quantitative easing works: to buy any amount of Italian bonds, Draghi has to buy twice as many Bunds.281 That is the only way the ECB could pull off QE ‘euro-style’. In other words, the only way of convincing German Chancellor Angela Merkel and Bundesbank chairman Jens Weidmann to allow the ECB to do QE was that it purchased government debt in proportion to GDP or to ECB shareholding by member states.282 Same thing. Now, the problem is that Bunds are running out because German finance minister Dr Wolfgang Schäuble is not issuing them—he is running a surplus. German financial institutions have an obligation to retain the Bunds they have. So you have excess demand for Bunds. This is creating problems for the smaller banks in Germany and the pension funds. And that is pushing Draghi into tapering already, and why the ECB’s programme of QE is going to be withdrawn very soon.283

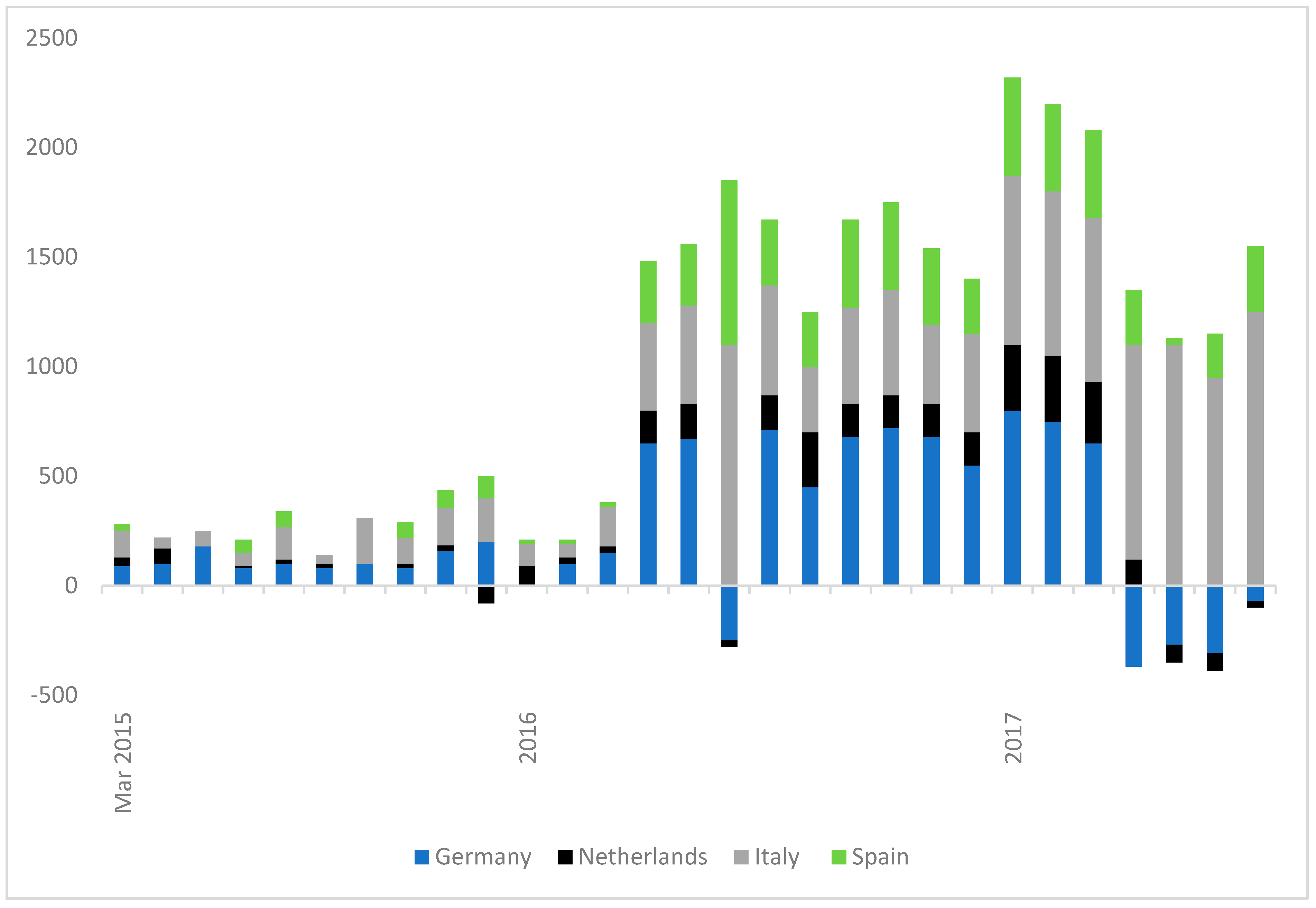

Figures for July [see Figure 33] show that, for the fourth month in a row, German bonds bought under the European Central Bank’s public sector purchase [i.e., QE] programme (PSPP) fell short of the amount allowed by the ‘capital key’ allocation. Other countries have also seen significant deviations from the capital key, under which bonds are bought in proportion to the share of the ECB capital provided by each country. This figure is determined by the size of GDP and population, and is adjusted slightly to reflect the ineligibility of Greek bonds given their low credit rating.284

Since April, the ECB has bought an additional €4.2 bn of Italian bonds and €809 m of Spanish bonds, against an under-purchase of €1.09 bn for Germany and (since May) €172 m for the Netherlands. The divergence suggests growing difficulties with the ECB’s quantitative easing programme and has reignited speculation about a tapering of bond purchases.

These figures mark a significant break from the pattern that existed for the two years from the start of the PSPP in March 2015 until March 2017. During that period the ECB over-purchased German and Dutch bonds by a total of €8.3 bn and €2.3 bn respectively. Italian and Spanish bonds were also over-purchased to compensate for the scarcity of bonds in smaller euro area countries, including Cyprus, Estonia and Portugal. However, the scale of Italian and Spanish bond over-purchasing has increased rapidly this year. Since January the ECB has overshot Italy’s adjusted capital key by an average of €920 m per month and Spanish bonds by €311 m per month. This compares with €264 m and €181 m respectively each month from the start of the PSPP to the end of 2016. In July, the over-purchase of Italian bonds reached more than €1.2 bn, the highest monthly figure to date.

Mario Draghi, president of the ECB, reiterated in late June that the bank remains committed to QE through bond purchases. But the longer QE goes on, the greater the demand will be for bonds in core countries. In the coming months, the amount of eligible bonds could begin to face significant strains. To avoid a sudden fall in the amount of German bonds available, or a politically toxic redistribution of the capital key to allow higher allocations to bonds from southern countries, Germany is scaling back the rate at which its own bonds are purchased.

…As the ECB remains committed to doing ‘whatever it takes’ to return the euro area to stability and growth, new tools could be needed as the potential limits of QE edge ever closer.285

10.2. The Second Phase of QE in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic Is Perpetuating a Real Estate Bubble

…in its [November 2021] Financial Stability Review,293 the European Central Bank issued an angst-ridden warning: Europe is facing a self-perpetuating debt-fueled real estate bubble. What makes the report noteworthy is that the ECB knows who is causing the bubble: the ECB itself, through its policy of quantitative easing—a polite term for creating money on behalf of financiers. It is akin to your doctors alerting you that the medicine they have prescribed may be killing you.

The scariest part is that it is not the ECB’s fault. The official excuse for QE is that once interest rates had fallen below zero, there was no other way to counter the deflation menacing Europe. But the hidden purpose of QE was to roll over the unsustainable debt of large loss-making corporations and, even more so, of key Eurozone member states (like Italy).

Once Europe’s political leaders chose, at the beginning of the euro crisis a decade ago, to remain in denial about massive unsustainable debts, they were bound to throw this hot potato into the central bank’s lap. Ever since, the ECB has pursued a strategy best described as perpetual bankruptcy concealment.

Weeks after the pandemic hit, French president Emmanuel Macron and eight other Eurozone heads of government called for debt restructuring via a proper Eurobond. In essence, they proposed that, given the pandemic’s appetite for new debt, a sizeable chunk of the mounting burden that our states cannot bear (unassisted by the ECB) be shifted onto the broader, debt-free, shoulders of the EU. Not only would this be a first step toward political union and increased pan-European investment, but it would also liberate the ECB from having to roll over a mountain of debt that EU member states can never repay.

Alas, it was not to be. German Chancellor Angela Merkel summarily killed the idea, offering instead a Recovery and Resilience Facility,294 which is a terrible substitute. Not only is it macroeconomically insignificant; it also makes the prospect of a federal Europe even less appealing to poorer Dutch and German voters (by indebting them so that the oligarchs of Italy and Greece can receive large grants). And, despite an element of common borrowing, the recovery fund is designed to do nothing to restructure the unpayable debts that the ECB has been rolling over and over—and which the pandemic has multiplied.

So, the ECB’s exercise in perpetual bankruptcy concealment continues, despite its functionaries’ twin fears: being held to account for the dangerous debt-fueled bubble they are inflating, and losing their official rationale for QE as inflation stabilises above their formal target.

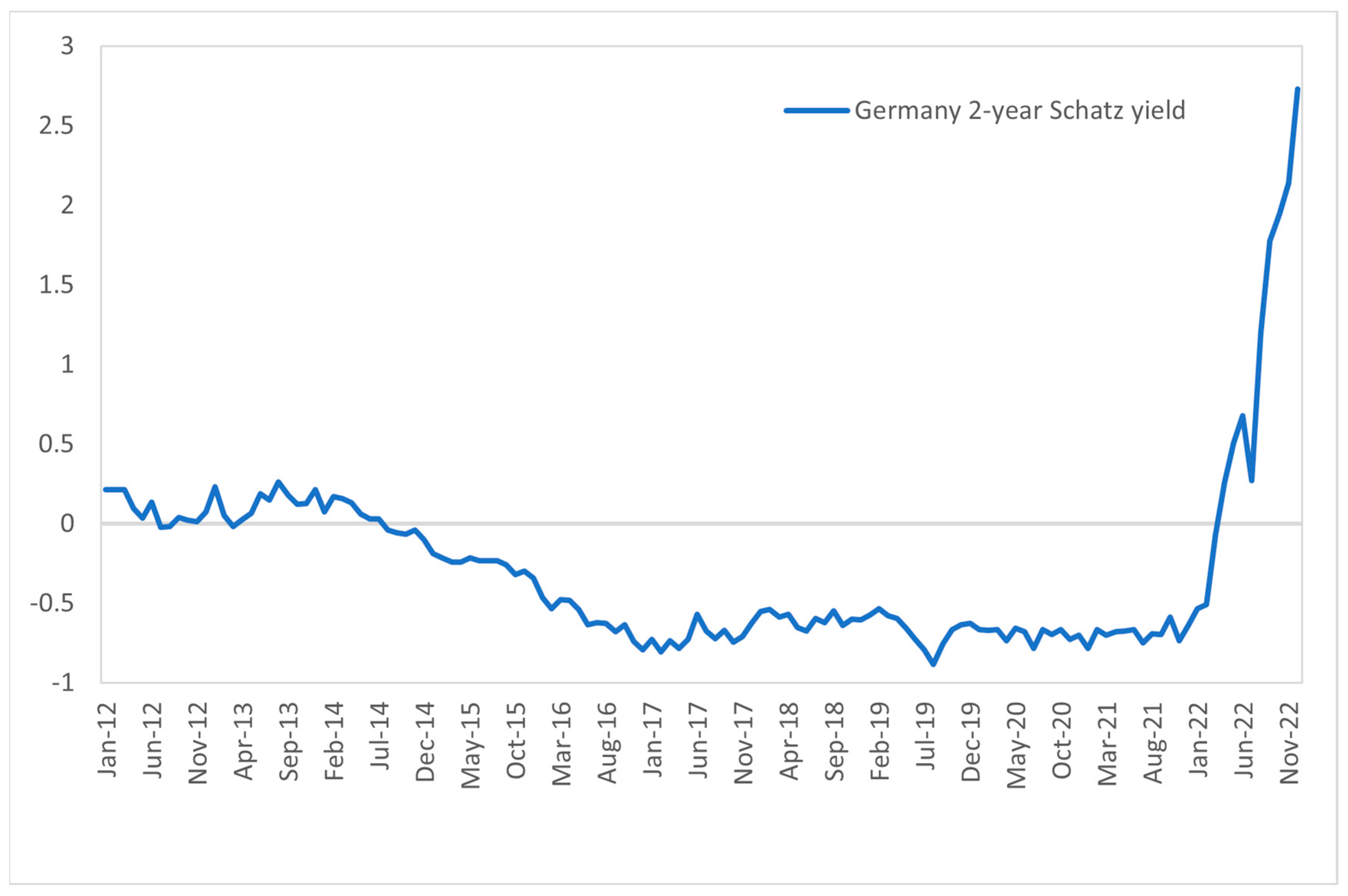

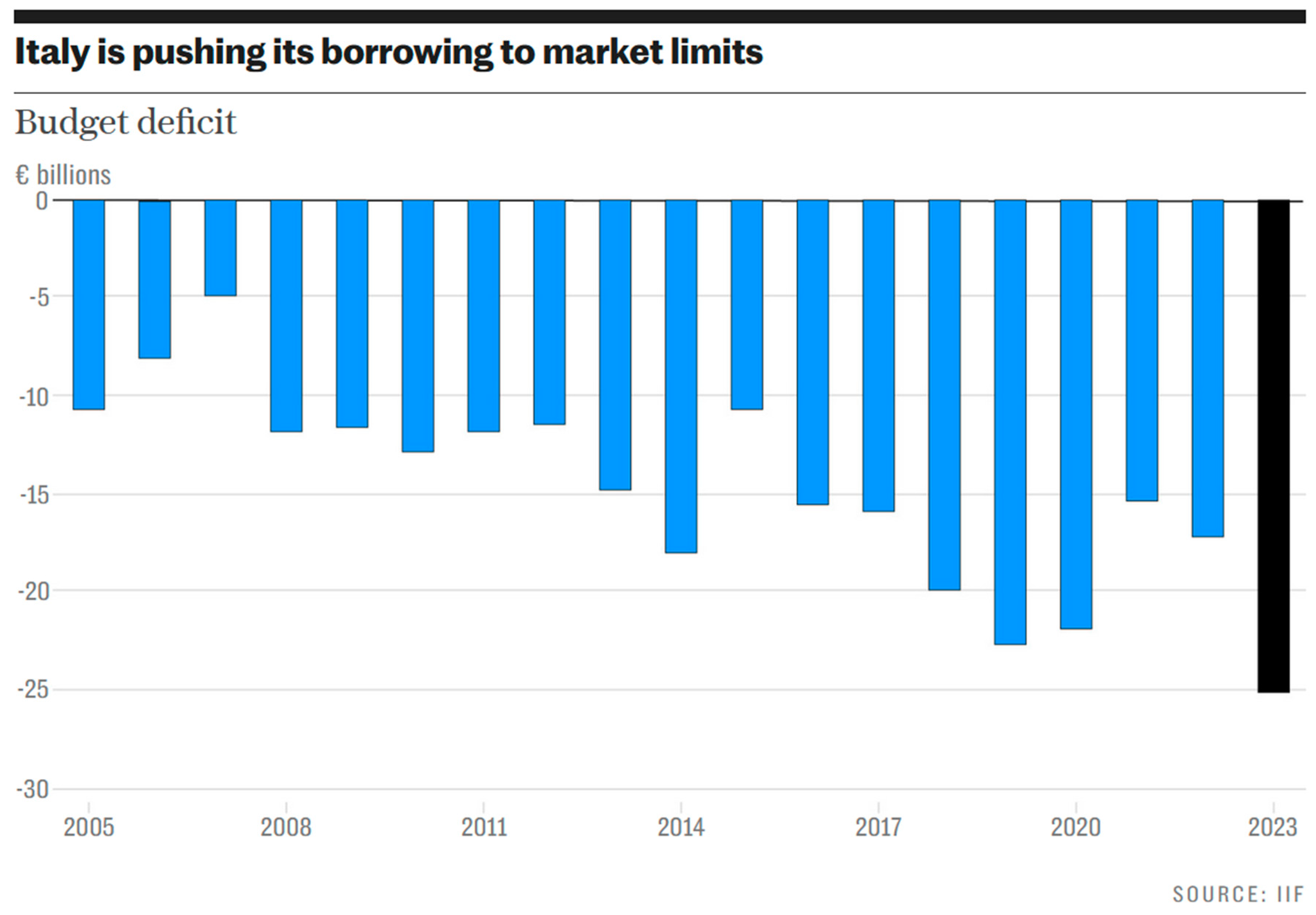

10.3. The Third Phase of QE—Winding Down, except in the Case of Italy

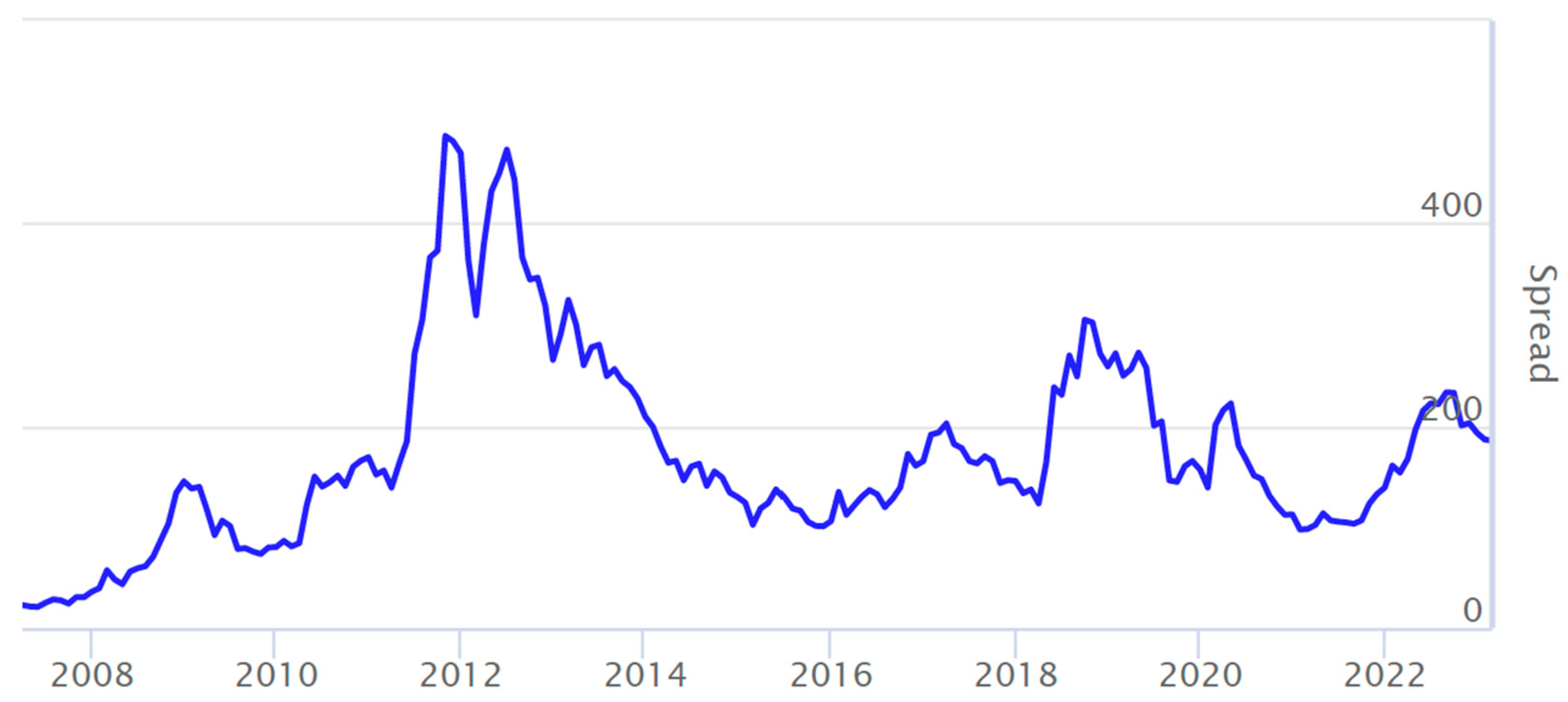

can be activated to counter unwarranted, disorderly market dynamics [namely a severe widening of the spread between the yields on member state government bonds] that pose a serious threat to the transmission of monetary policy across the euro area. By safeguarding the transmission mechanism, the TPI will allow the [ECB] to more effectively deliver on its price stability mandate.

Subject to fulfilling established criteria, the Eurosystem will be able to make secondary market purchases of securities issued in jurisdictions experiencing a deterioration in financing conditions not warranted by country-specific fundamentals, to counter risks to the transmission mechanism to the extent necessary. The scale of TPI purchases would depend on the severity of the risks facing monetary policy transmission. Purchases are not restricted ex ante.

TPI purchases would be focused on public sector securities (marketable debt securities issued by central and regional governments as well as agencies, as defined by the ECB) with a remaining maturity of between one and ten years. Purchases of private sector securities could be considered, if appropriate.

…[The established] criteria include: (1) compliance with the EU fiscal framework:328 not being subject to an excessive deficit procedure (EDP), or not being assessed as having failed to take effective action in response to an EU Council recommendation under Article 126(7) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU); (2) absence of severe macroeconomic imbalances: not being subject to an excessive imbalance procedure (EIP) or not being assessed as having failed to take the recommended corrective action related to an EU Council recommendation under Article 121(4) TFEU; (3) fiscal sustainability: in ascertaining that the trajectory of public debt is sustainable, the [ECB] will take into account, where available, the debt sustainability analyses by the European Commission, the European Stability Mechanism, the International Monetary Fund and other institutions, together with the ECB’s internal analysis;329 (4) sound and sustainable macroeconomic policies: complying with the commitments submitted in the recovery and resilience plans for the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF)330 and with the European Commission’s country-specific recommendations in the fiscal sphere under the European Semester.

…Purchases would be terminated either upon a durable improvement in transmission, or based on an assessment that persistent tensions are due to country fundamentals.

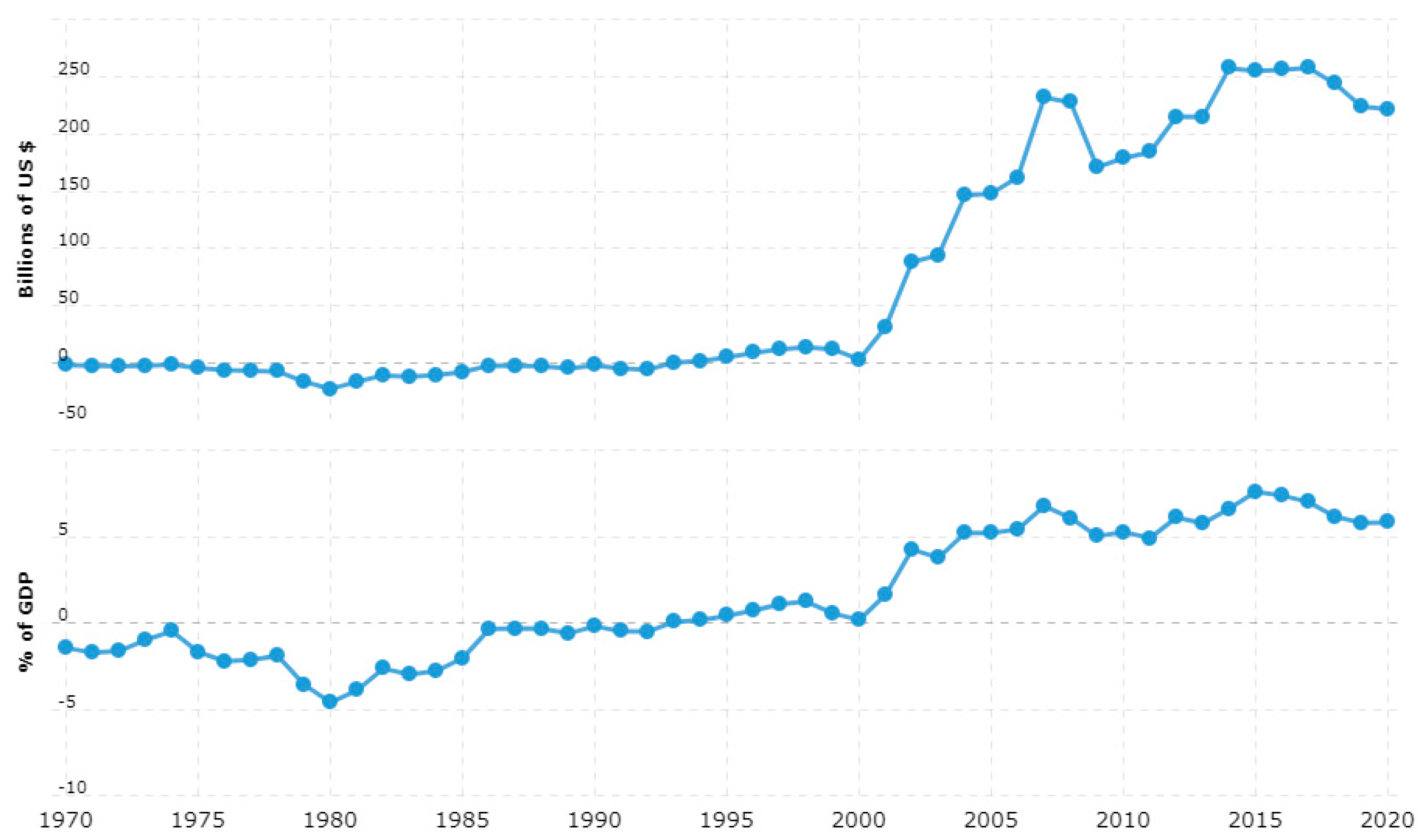

It is politically impossible to keep mopping up Italy’s debt issuance under the guise of monetary policy. The euro’s crash to dollar parity has been the last straw. The Bundesbank has lost patience. The ECB is in the worst internal disarray since the depths of the Eurozone debt crisis. Hawks and doves are contradicting each other daily on fundamental strategy. Markets have no idea how the new ‘anti-spread’ tool (TPI) to protect Italy is supposed to work, or whether it is legal outside an emergency. ‘It is a complete shambles. Christine Lagarde has lost control and is not showing any leadership’, said one source close to the Bundesbank.

… Isabel Schnabel, Germany’s [former] member of the [ECB Governing] Council, …said ‘Our currencies are stable because people trust that we will preserve their purchasing power. Failing to honour this trust may carry large political costs. …History is full of examples of high and persistent inflation causing social unrest. Sudden and large losses in purchasing power can test even stable democracies. …Determined action is needed to break these perceptions. … [The ECB] must engineer a recession now to avoid something worse later’. This is the voice of the old Bundesbank.

It was an explicit warning that the ECB would no longer set policy to cap the bond yields of vulnerable states. Hedge funds could hardly receive a clearer invitation to revive the ‘short Italy’ trade.

‘We’ve been short since the beginning of the year. It seemed like Italy’s problems had gone away, but that was only because the ECB was buying more than 100 pc of net debt supply. They can’t keep doing that now’, said Mark Dowding from BlueBay Asset Management.

The International Monetary Fund said in its latest ‘Article IV’ report that foreigners have pulled a net €70 bn out of Italy over the last six months. It warned of a ‘vicious cycle between the sovereign and banks’ as yields rise on Italian debt.

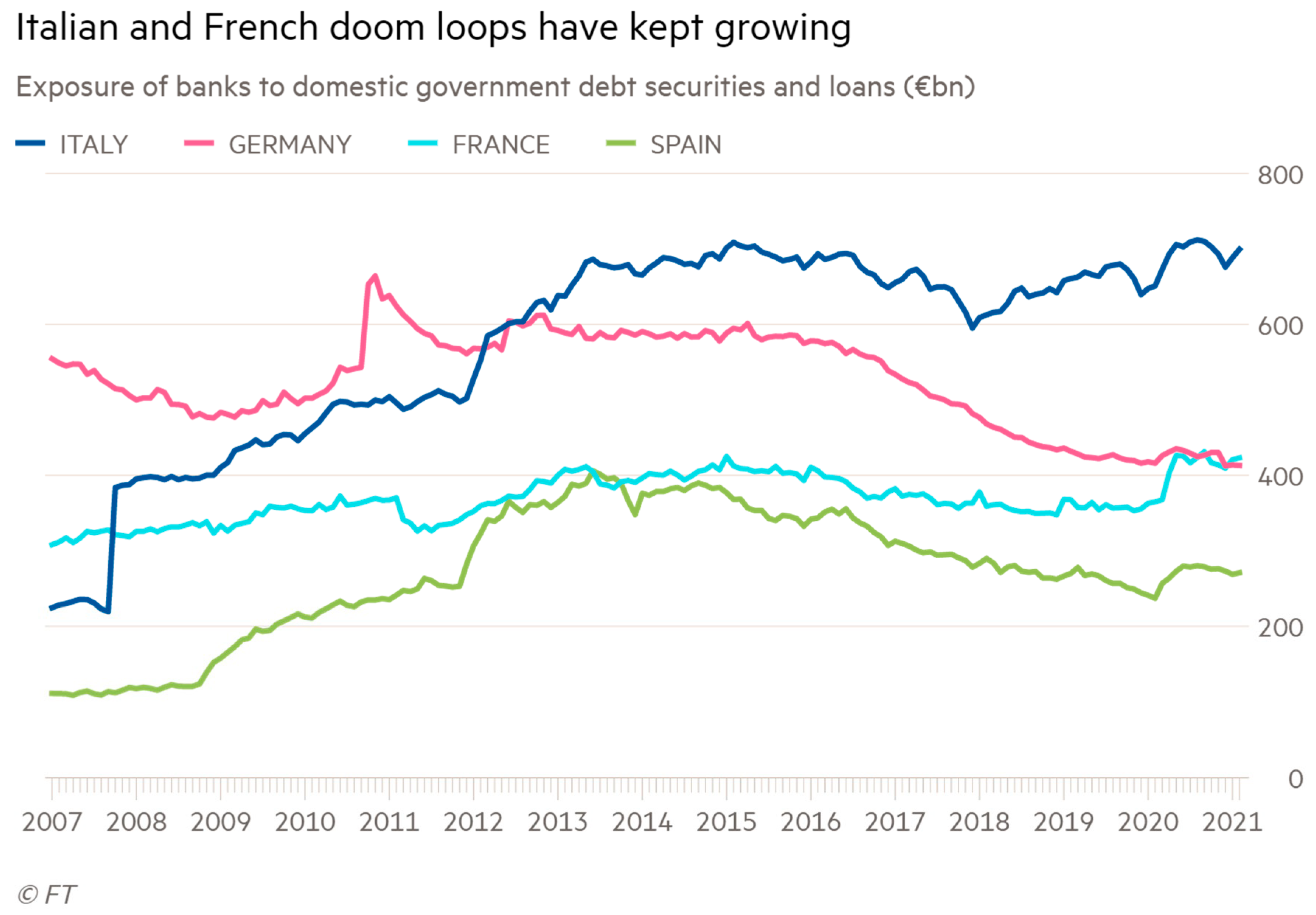

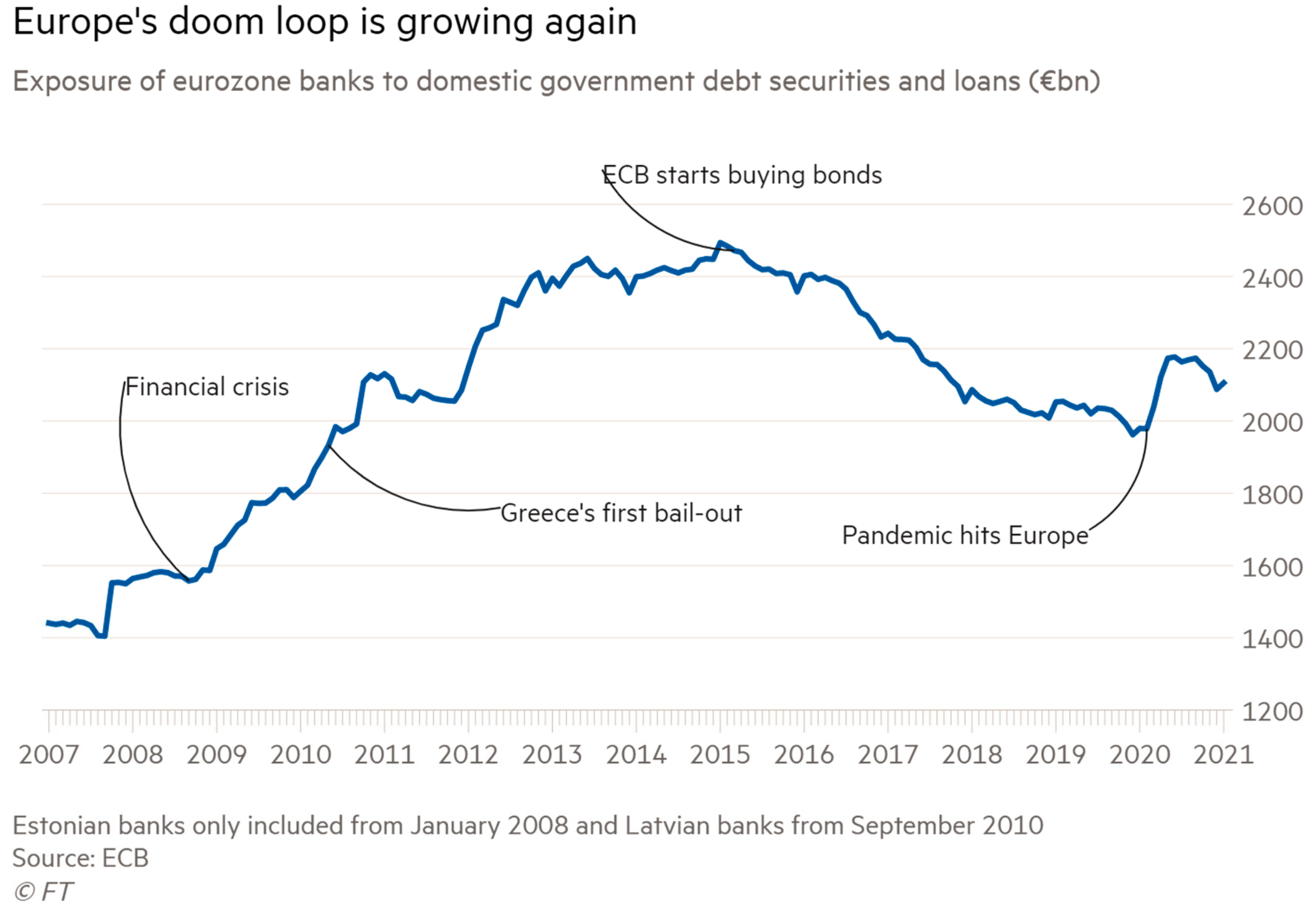

The risk is more concentrated than a decade ago, since QE actively encouraged Italian banks to play the carry trade and acquire even more Italian sovereign debt. The infamous doom-loop of 2011–2012 is alive and well. The Eurozone Banking Union that was supposed to eliminate this uniquely European disorder never happened.

…The IMF described a possible chain-reaction where rising yields cause losses for banks, which then tighten loans, causing a credit crunch, which in turn leads to a deeper downturn in a pernicious spiral.

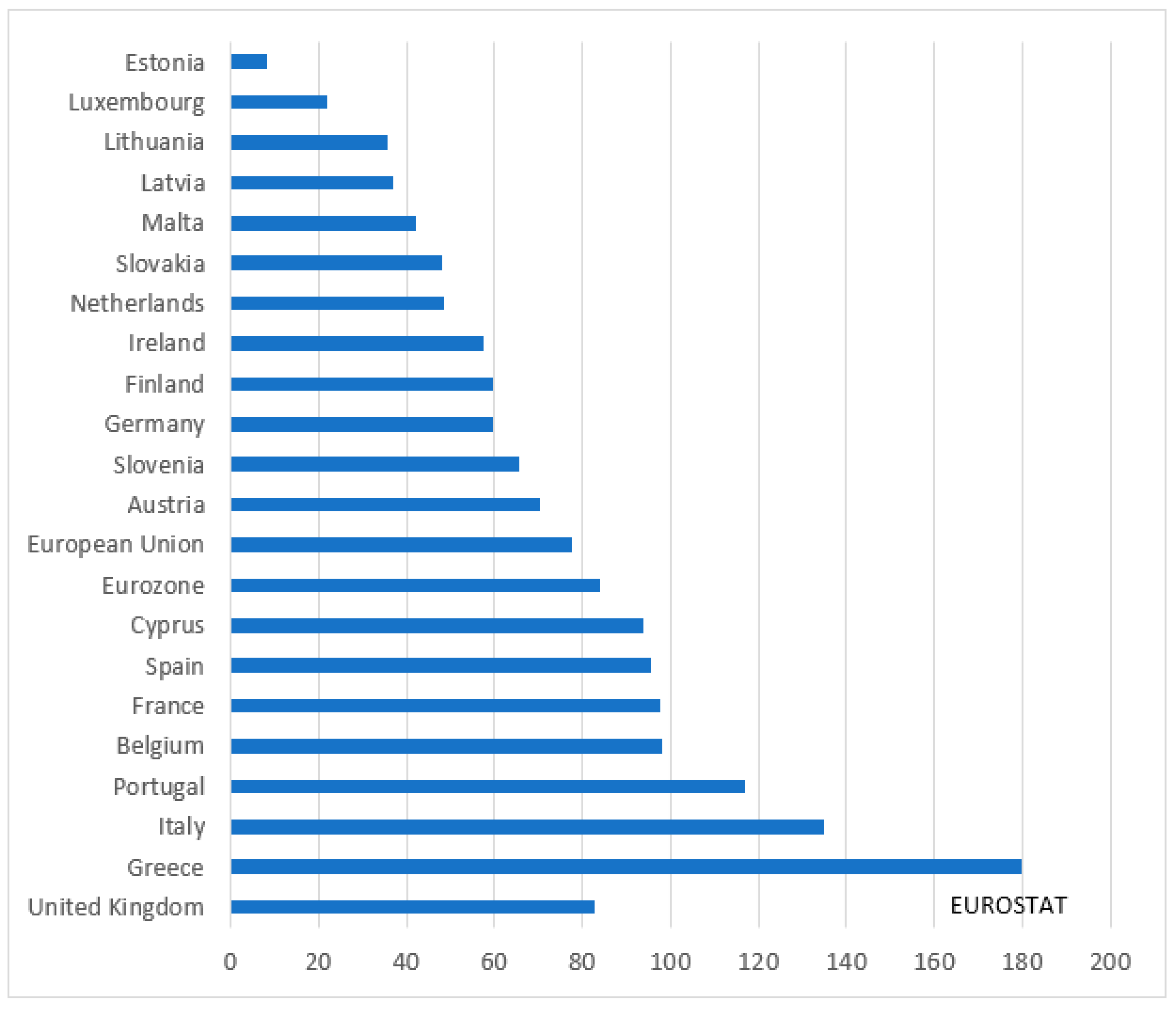

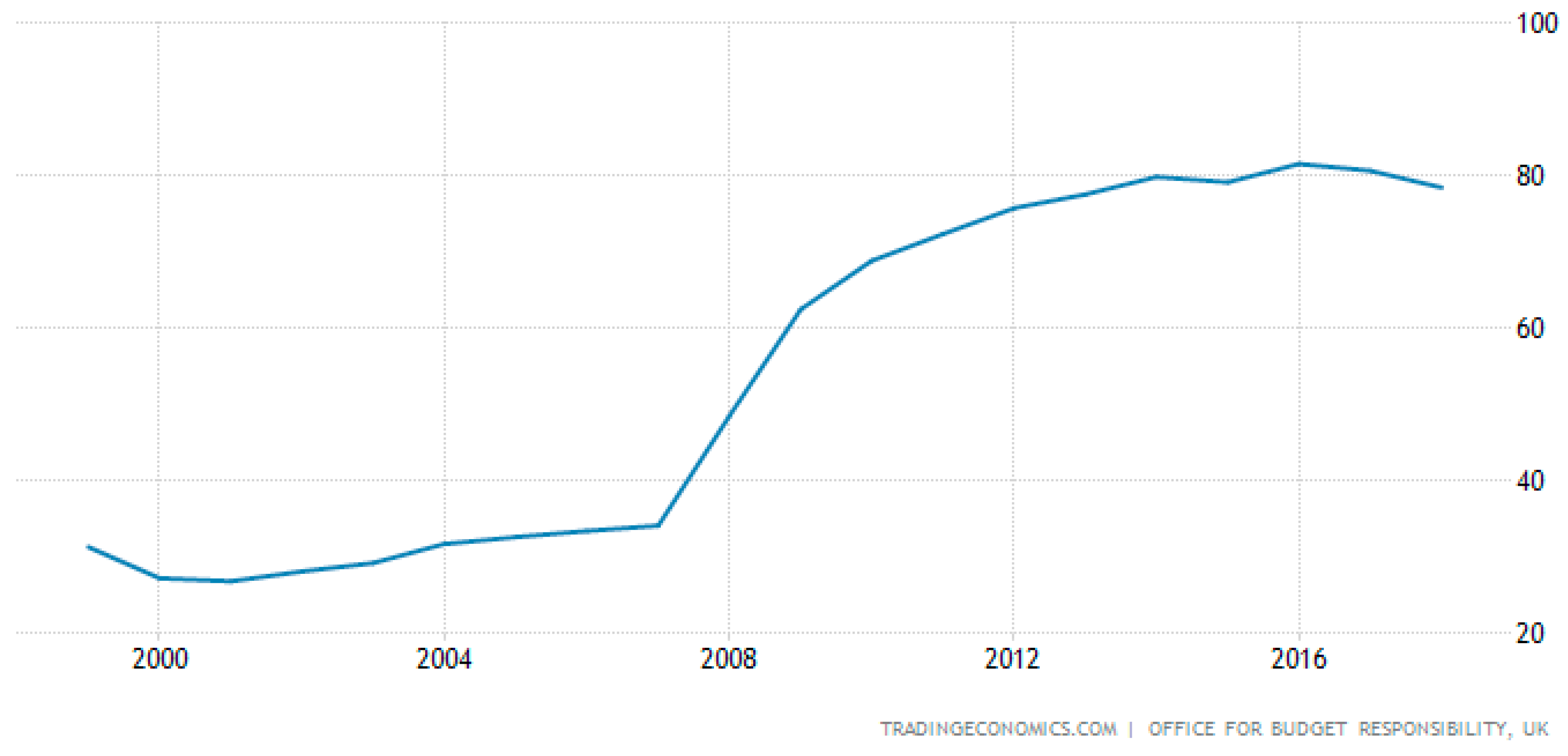

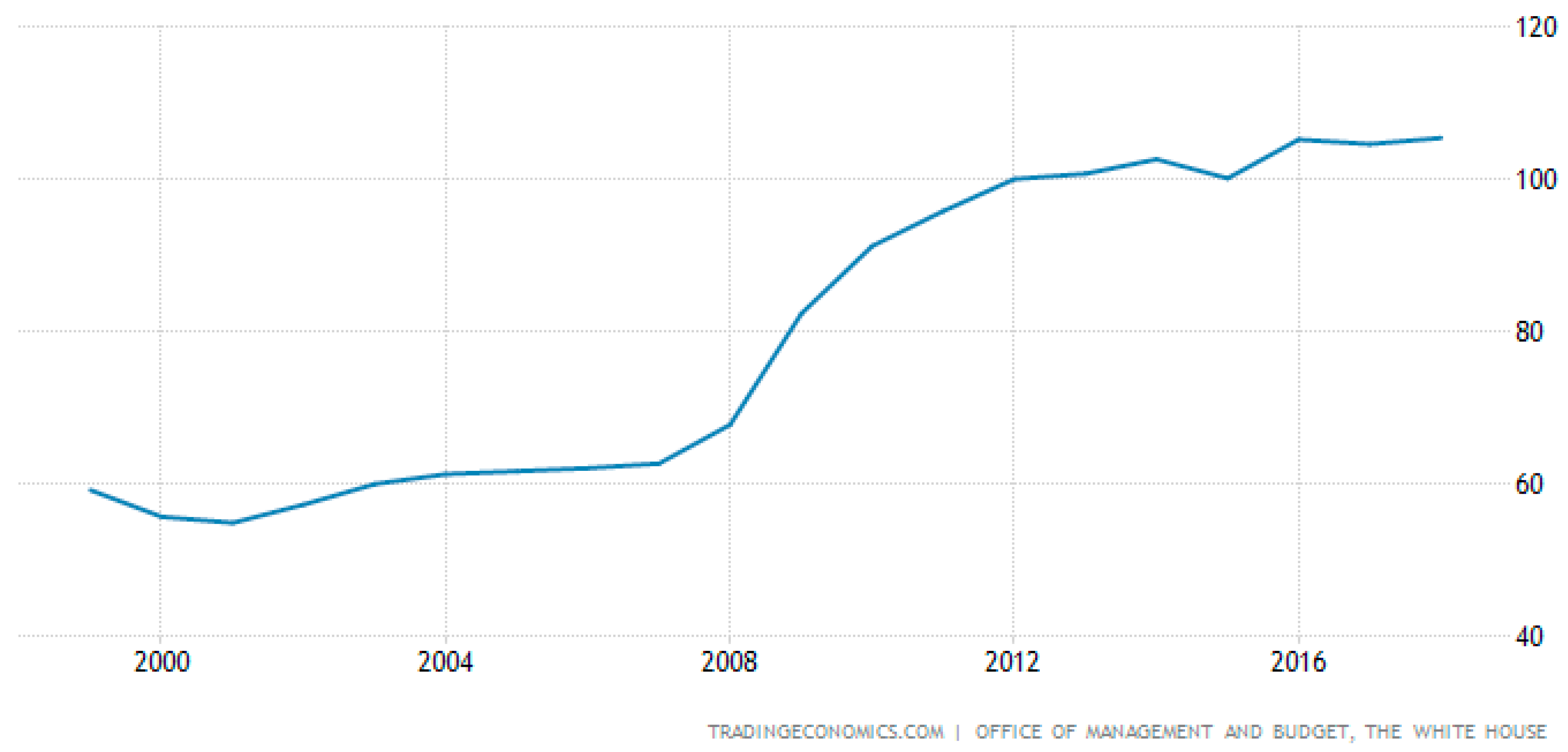

…Italy has emerged from the pandemic with a debt burden of 150% of GDP, 15 points higher than pre-Covid and nearing the point of no return for a sub-sovereign borrower unable to control its own currency. It has further liabilities to the ECB’s Target2 payments nexus near 30% GDP.

…Italy’s core problem is the toxic mix of high public debt intersecting with a trend growth rate near zero. One shocking detail in the IMF’s report is that total factor productivity has fallen by 13.5% since 2000.

Mr Draghi has not had time to drive through the radical reforms needed to rescue Italy from this bad equilibrium. His planned shake up of the pension and tax systems has stalled.

…’The ECB can’t give Rome a blank cheque, and it can’t keep pushing the envelope on monetary financing of debt’, said BlueBay’s Mr Dowding.

For now, the ECB is skewing redemptions of its bond portfolio away from Bunds and into Italian bonds, and on an eye-watering scale. This has technical limits and is a clear violation of the Maastricht Treaty’s no bail-out clause the longer it goes on.

The TPI was unveiled in early July but the details have yet to be ironed out. Nothing has yet appeared in the Journal Officiel and the instrument is not legally valid until it does so.

David Marsh, head of the Official Monetary and Financial Institutions Forum, said there are unresolved questions over who bears the financial risk of TPI interventions. It is unclear whether the tool constitutes a fiscal risk and therefore breaches the budgetary sovereignty of the German Bundestag, and whether it is compatible with past rulings by the German Constitutional Court.

‘The TPI can be activated only if there is contagion and a whole lot of countries are under pressure’, said Peter Schaffrik from RBC Capital. ‘If push comes to shove, the ECB will be there to buy Italian debt. But could the spreads go to 300 first? Yes they could’.

…The real danger for Italy is that it might be asphyxiated slowly by untenable borrowing costs that stay high and that expose the underlying pathologies of the economy over time, until something snaps.

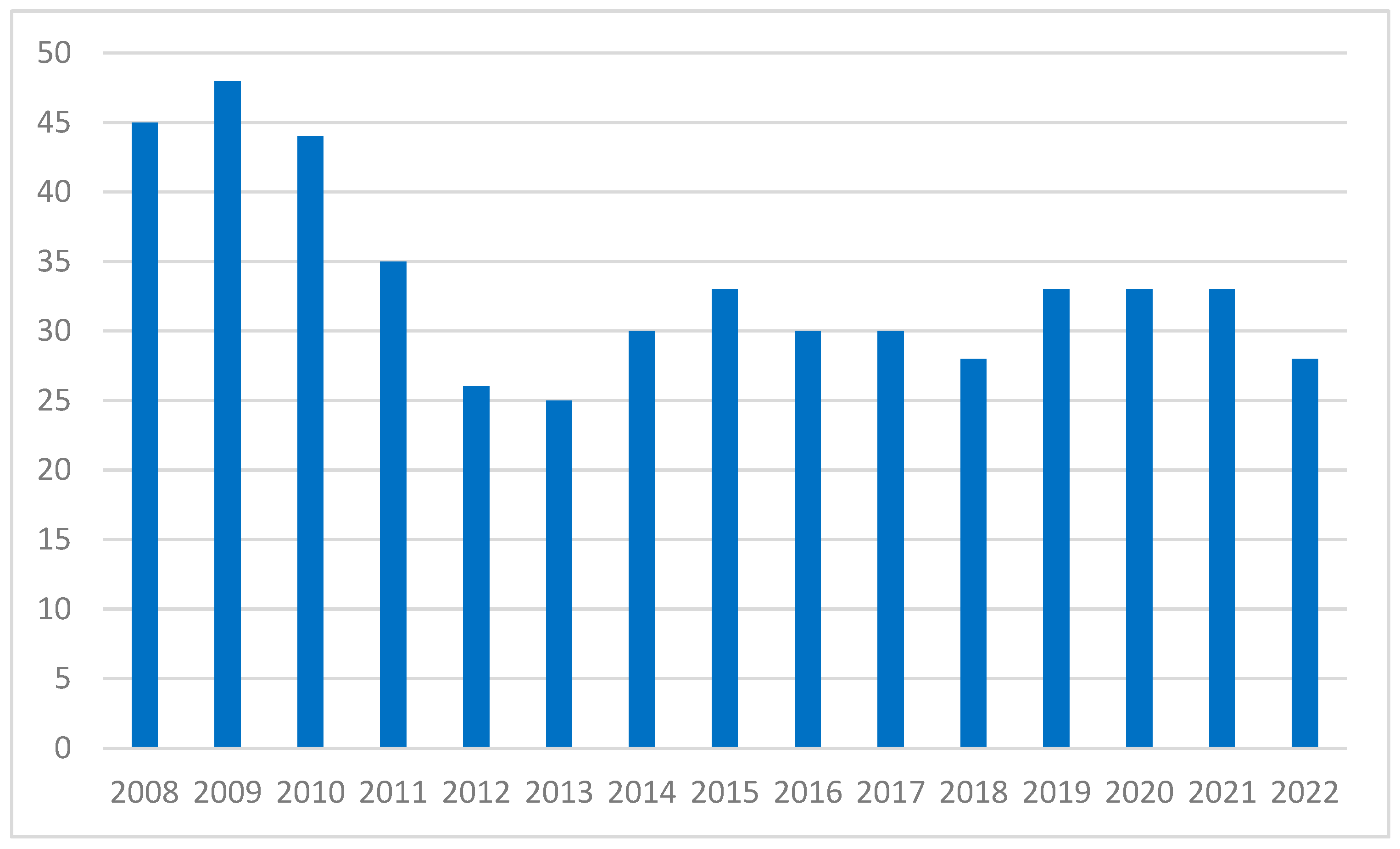

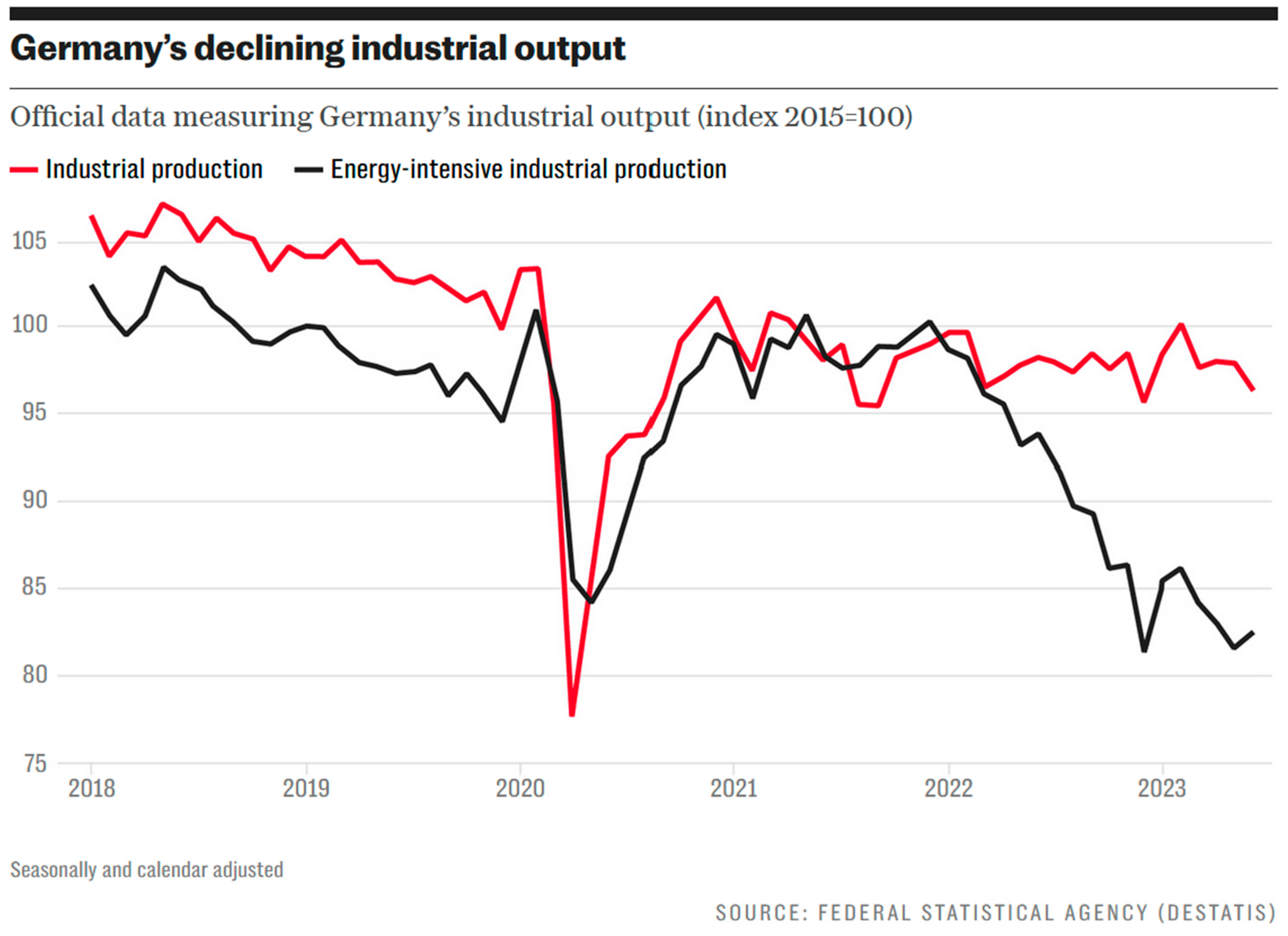

After coasting on an undervalued currency, cheap energy, and a booming China, Germany is stuck in a spiral of decline. …Germany got extraordinarily lucky in the first two decades of this century. The replacement of the mighty Deutschemark with the far weaker euro meant that its currency was dramatically undervalued, allowing it to build up huge trade surpluses and dominate a vast range of industries where it may otherwise have been unable to compete. The industrialisation of China, meanwhile, was built on German machine tools creating a huge new market for the country’s formidable engineering firms. And it had access to what seemed like an endless supply of cheap Russian gas, allowing it to continue with heavy, power-hungry industries—the huge BASF plant in Ludwigshafen uses about as much gas as the whole of Switzerland—long after they would have been obsolete elsewhere. Add it all up, and this happy combination of circumstances created an illusion of permanent prosperity that allowed Germany during the Merkel era to complacently lecture the rest of the world on the brilliance of its consensual model, while racking up trade surpluses as if they would last forever. That luck has now run out. The war in Ukraine meant that the Russian gas had to be turned off, and given the ridiculously self-indulgent decision to close its nuclear plants, Germany only managed to avoid blackouts by paying eyewatering prices for energy on the global market. Factories are already closing because they can’t afford power. China seems to have bought all the German technology it needs, and is now turning the tables mercilessly on its former tutor. Led by the likes of BYD, the Chinese auto companies could well be about to destroy the German auto giants, and the EU’s planned tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles seem like they will be too late to save them. …Meanwhile, Germany has failed to digitise, with the fax machine still an everyday piece of kit. The country that capitalised so well on the first and second industrial revolutions is nowhere in the third. …But the real problem is deeper. Germany’s consensual, coalition-based political system…is incapable of pushing through the radical change and modernisation the country needs. …It is possible that Germany will reform itself one day. It is still a rich country, with a highly skilled workforce, a huge depth of technical talent and a huge presence in global markets. But it will take a radical overhaul of its political system, and a shattering of the complacent centrism that dominates its internal debate before that happens. And there is little sign of any such move on the horizon.

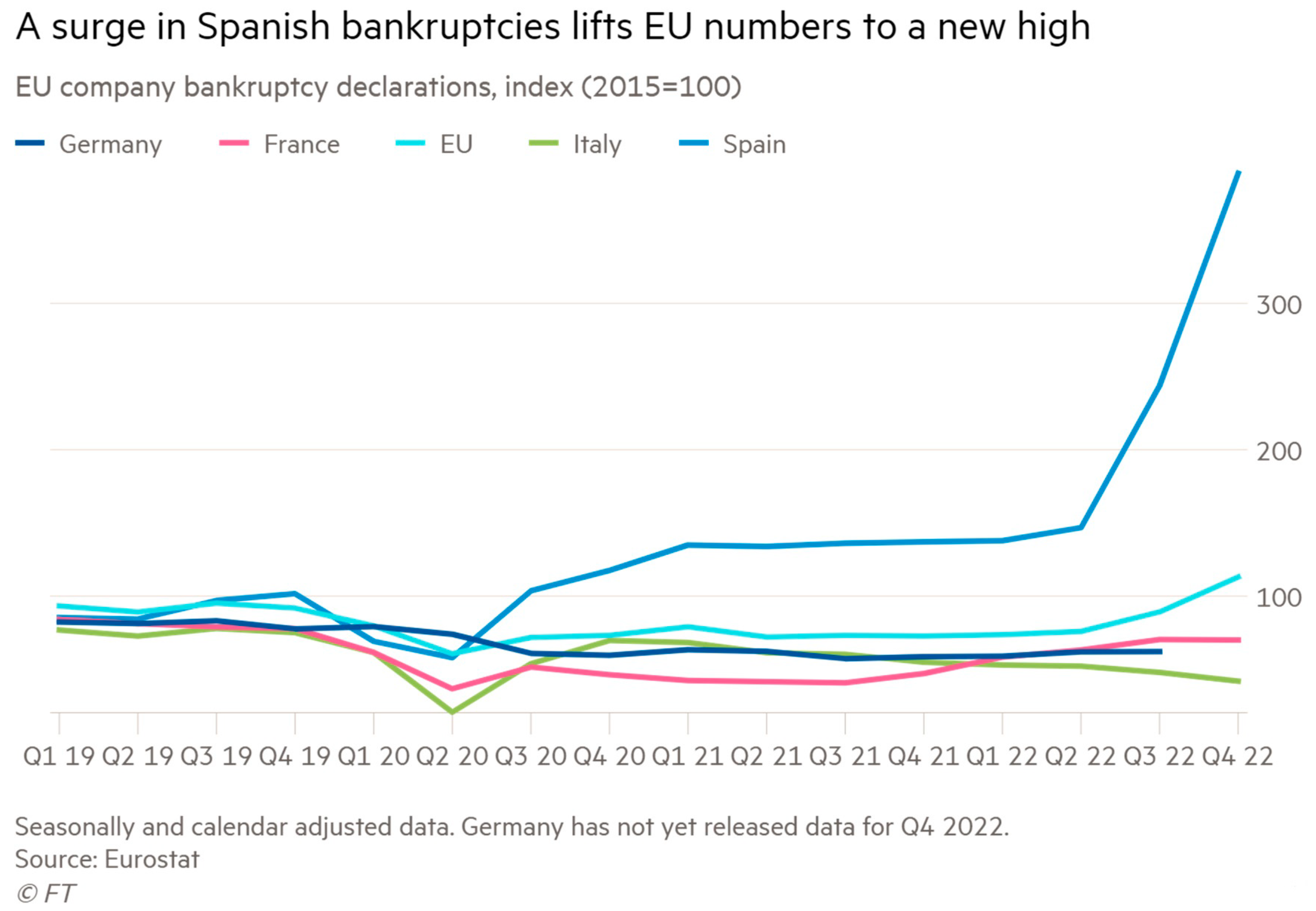

10.4. The Fourth Phase of QE—Quantitative Tightening

Lending is deteriorating most rapidly in Italy and Spain. ‘The tightening in financing conditions corroborates our view that the euro area is headed towards a sharp recession’, said Ludovio Sapio from Barclays. Trouble is baked into the pie already, whatever happens to Vladimir Putin’s war and global gas prices. Banks are doing what they always do at the rumble of thunder: they are imposing tougher terms on households and small firms; they are rejecting loan applications. This is a self-fulfilling process that can spin out of control at turning points in the business cycle. Ignazio Visco, governor of the Bank of Italy, warned … of a ‘serious credit crunch’ if the ECB tightens too hard into the downturn. Businesses are battening down the hatches, limiting borrowing to what is strictly necessary to stay afloat. Homeowners are baulking at soaring mortgage costs.

… [B]anks will lose a key prop just as they face the hit from the global bond market crash. They were induced to accumulate government debt under Quantitative Easing. Those banks most invested in this sovereign bank doom-loop now carry large paper losses that must be ‘marked to market’. This erodes their capital ratios, forcing them to curtail lending.

… The ECB faces an excruciating dilemma. … The founding contract of the euro was that the ECB should be as rigorous as the Bundesbank, and the euro should be as hard as the D-Mark. That contract looks like a quaint relic today. But it would be tempting fate to assume that Germany will tolerate double-digit inflation for long, or that it will allow the ECB to keep tilting policy towards the needs of Club Med debtors in the cause of euro solidarity.

The German economic establishment thinks the country is on the cusp of a wage-price spiral…. There is an even deeper problem of social cohesion. Inflation is toxic in Germany because of deep-rooted cultural traditions. Half of Germans rent rather than own property. They typically keep their savings in bank accounts, and have no financial assets. They have entirely missed out on the compensating wealth gains of the last decade. Gefühlte Inflation—the inflation that shoppers feel—is running at twice the official CPI rate.

… Volker Wieland, a former member of the German Council of Economic Experts, said inflation had reached the point where nothing short of sharply positive real rates will be enough to break the fever. ‘Inflation is going to become entrenched unless the central bank acts’, he said.

Positive real rates are precisely what Italy cannot endure. It is why premier Giorgia Meloni lashed out at the ECB on her first day in office, denouncing rate rises on the cusp of recession as precipitous.

… Mrs Meloni is now in implicit alliance with France’s Emmanuel Macron, who has also castigated unnamed monetary hawks at the ECB. His demarche is logical: France has an even bigger debt burden than Italy. Data from the Bank for International Settlements shows that total public and private debt (non-financial) is 351% of GDP in France, up 70 percentage points over the last decade. The comparable figure is 276% in Italy, and 271% in the UK, and 199% in Germany.

It is not that Germany is right, or that Italy and France are right. They are all right. This conflict is what happens if you impose a single coin and a single interest rate on a disparate region that fails every key test of Robert Mundell’s Optimal Currency Area.

… Thomas Mayer…said the ECB has already gone beyond the point of no return. It has become a fiscal captive, much as the Bank of Italy was captive of the Italian treasury under the lira. ‘We have see the “liraisation” of the euro’, he said. He predicts that the EMU experiment will end in much the same way as the Latin Monetary Union in the 19th century. Switzerland eventually pulled out because it lost patience with chronic debasement. The eurozone is a sturdier beast but the pressures are the same. ‘It can’t survive’, he said.

10.5. Is the QE Programme Legal under EU Law?

[It] is not bound by the [ECJ’s] decision competences conferred upon the ECB, which are limited to monetary policy. Rather, it [the ECJ’s 11 December 2018 ruling] allows the ECB to gradually expand its competences on its own authority. The PSPP improves the refinancing conditions of the member states as it allows them to obtain financing on the capital markets at considerably better conditions than would otherwise be the case; it thus has a significant impact on the fiscal policy terms under which the member states operate. In particular, the PSPP could have the same effects as financial assistance instruments pursuant to Art. 12 et seq. ESM [European Stability Mechanism] Treaty.

The PSPP also affects the commercial banking sector by transferring large quantities of high-risk government bonds to the balance sheets of the Eurosystem, which significantly improves the economic situation of the relevant banks and increases their credit rating. The economic policy effects of the PSPP furthermore include its economic and social impact on virtually all citizens, who are at least indirectly affected, inter alia as shareholders, tenants, real estate owners, savers or insurance policy holders. For instance, there are considerable losses for private savings. Moreover, as the PSPP lowers general interest rates, it allows economically unviable companies to stay on the market. Finally, the longer the programme continues and the more its total volume increases, the greater the risk that the Eurosystem becomes dependent on member state politics as it can no longer simply terminate and undo the programme without jeopardising the stability of the monetary union.

….Following a transitional period of no more than three months allowing for the necessary coordination with the Eurosystem, the Bundesbank may thus no longer participate in the implementation and execution of the ECB decisions at issue, unless the ECB Governing Council adopts a new decision that demonstrates in a comprehensible and substantiated manner that the monetary policy objectives pursued by the PSPP are not disproportionate to the economic and fiscal policy effects resulting from the programme. On the same condition, the Bundesbank must ensure that the bonds already purchased and held in its portfolio are sold based on a—possibly long-term—strategy coordinated with the Eurosystem.

11. Can a Country Leave the Eurozone?

…the euro is not irreversible. Indeed, … exit risk is an unavoidable feature of monetary union. Thus, if a country’s Eurosystem debt presents a risk when it leaves the euro, and if there is a non-zero probability that it will leave, then its Eurosystem debt is risky. A contingent risk is a risk.

… The departure of any country from monetary union would involve large political and financial costs and uncertainty, particularly for that country but also for other Eurozone members, given the absence of agreed exit procedures. This makes monetary union more durable than a fixed rate regime between separate currencies.

Yet, there must be a limit to the tolerance of creditor countries. There must be some threshold level of exposure to Greece or any other debtor country, or expected future exposure, beyond which Germany and the other creditors would refuse further credit either via the Eurosystem or official loans, accept their losses, and expel.

Despite the ECB’s assertion that monetary union is irreversible, exit risk will always be present, just as it is in any ordinary fixed exchange rate regime. The difference with monetary union is that it raised the stakes by cementing all financial claims into a ‘foreign’ currency.

The Greek government knows this. Indeed, the fear of being deprived of Emergency Liquidity Assistance and forced out of the euro391 was the main reason why it accepted the conditions attached to the [2015] bailout.392 Likewise, it was the threat to cut ELA that persuaded the Irish government to accept an official loan programme in November 2010 and the Cypriot government to accept a programme in March 2013.

Even if the Greek government runs large budget surpluses which it uses to repay its official loans, this will merely cause an equal rise in its Eurosystem (Target2) debt, unless the budget surpluses induce private financial inflows.396

While ‘austerity’ may be given the credit for turning round the Irish economy, the loan programmes for Greece have been notably unsuccessful and there has been mixed success elsewhere. The argument has been made [e.g., by Varoufakis] that austerity in Greece may have improved economic efficiency and budget balances, but that the dominant effect has been to depress economic activity and create political instability, making the repayment of loans less likely.

Greece cannot afford the primary surplus the Eurogroup399 has called for…

Debts which cannot be repaid will not be repaid. That’s why we have bankruptcy in the first place. Or, when it comes to sovereign nations, we have debt rescheduling and IMF programmes instead of bankruptcy.

When the Greek crisis first blew up, what should have happened was the standard IMF programme: a haircut on the debt, devalue the currency and a bit of a loan to tide things over until growth returned. This is similar to the approach taken by Iceland—which has already recovered while Greece languishes—and is what the IMF has been doing for decades in other places.

The one thing standing between Greece and this approach was the euro. In order to protect the integrity of the single currency, debts to the private sector banks were refinanced by public money from varying combinations of the EU itself, the ECB, the Eurogroup, the IMF and so on.

This is the crucial point. There are no private sector capitalists left. If there were, we could simply say ‘you lost your money, better luck next time’. Instead there are only official creditors, run by politicians, who have their voters wondering what has happened or will happen to their money.

For it is still true that Greece cannot repay those debts, and therefore Greece will not repay them. All that can change is who will lose money and when. Unsurprisingly, politicians are keen to delay the inevitable until they have retired and are collecting their pensions. That the Greeks have to see theirs cut in the interim is just bad luck.

…The Greek debt crisis is a contest between politics and reality.400

12. Is There a Political Solution to the Eurozone Problem?

- ‘There can be little doubt that the absence of a political union is a serious design flaw in the European monetary union that will have to be remedied to guarantee the long-run survival of the Eurozone’.403

- ‘European integration is a political process. The importance of the political origins, motivations and consequences of European integration cannot be overemphasised’.404

- ‘The EMU seems locked into a vicious circle, which had been foreseen long ago: “monetary unity imposed under unfavourable conditions will prove a barrier to the achievement of political unity”, Milton Friedman foresaw. But now political unity is precisely the necessary condition to save monetary unity’.405

- ‘EMU is impractical to the point of impossibility if…it is introduced before—rather in conjunction with—political union. In this context, political union must include a thorough-going centralisation of fiscal and debt management powers. There is no escape from the interdependence of political and monetary union. German politicians and Bundesbank officials have correctly emphasised that the two ideas are inseparable. Indeed, for many of Europe’s leaders, the great merit of EMU is that it is a building-block—perhaps the most important building-block—in the construction of political union. In view of the proliferation of official statements associating political and monetary union, Mr. Kenneth Clarke’s406 view that “I do not believe EMU is any threat to the continued existence of the nation state” is puzzling. At any rate, the EU will fail to create a single currency unless it simultaneously establishes a political union’.407

- ‘If the Eurozone follows the precedent of the 1930s, it will not survive. …A fully-federal Europe with a banking union and a fiscal union is the best solution to this problem but is politically infeasible’.408

…explore the dichotomy between French and German political-economic philosophies. The first values flexibility and solidarity and state intervention; the second stresses rules and consequences and free markets.

They note that France and Germany have in effect swapped sides in this debate. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the French had a strong tradition of economic liberalism, and the newly unified Germany believed in state-centered, state-directed economic policies. These biases were reversed by the disasters of Nazism and the Second World War. France’s wartime failure discredited its elites and their laissez-faire inclinations, and led to a heavy new emphasis on state planning, whereas Germany became obsessed with the idea of a rules-based liberalism. The product, known as ordoliberalism, involves a mixture of free-market economics with an attitude toward rules that approaches mystic reverence.415

…It is a matter of deep conviction [in Germany] that the euro must never be a ‘transfer union’. The Eurozone must never be about the rich paying for the poor, the North for the South. There are good historical reasons for this passionate adherence to fiscal rectitude, rooted in the causal link between deficits, runaway inflation, and the rise of the Nazis…. This theme in German thought runs very deep. A German government can’t follow the necessary policies without facing electoral disaster…. Where others see a crisis caused by weak demand, Germany sees a crisis caused by excessive use of cheap credit, which can be cured only by severe cuts in spending. …Chancellor Angela Merkel…talks fondly about the ‘Swabian housewife’, a figure of legendary common sense and frugality who, when times are hard, balances the books by cutting her spending.416

- ‘I’m ready to be insulted as being insufficiently democratic’.

- ‘If it’s a Yes, we will say “on we go”, and if it’s a No, we will say “we continue”’ (on the 2005 French referendum which failed to endorse the Commission proposal to introduce an EU constitution—only for the constitution to reappear in the Lisbon Treaty in 2009 which was approved without a referendum431).

- ‘We decide on something, leave it lying around and wait and see what happens. If no one kicks up a fuss, because most people don’t understand what has been decided, we continue step by step until there is no turning back’.

- ‘Of course there will be transfers of sovereignty. But would I be intelligent to draw the attention of public opinion to this fact?’ (on British calls for a referendum over the Lisbon Treaty).

- ‘There can be no democratic choice against the European Treaties’ (in ‘Greece: The dangerous game’, Le Figaro, 1 February 2015).432

13. Why Is the Problem with Target2 So Little Known?

How much longer will Germany’s hard-working, inflation-averse population tolerate paying for other countries’ excesses? There is considerable anger across the Eurozone’s largest economy, even though most voters don’t know the half of it. Obscure data shows that under so-called Target2 operations, the ECB’s intra-Eurozone payments system, the Bundesbank is owed a mighty €620 bn by other member states. This stealth bail-out dwarfs German’s covert contributions to previous Eurozone rescues, which themselves provoked bitter public criticism.

Vast liabilities are being switched quietly from private banks and investment funds onto the shoulders of taxpayers across southern Europe. It is a variant of the tragic episode in Greece, but this time on a far larger scale, and with systemic global implications.

There has been no democratic decision by any parliament to take on these fiscal debts, rapidly approaching €1 trillion. They are the unintended side-effect of quantitative easing by the European Central Bank, which has degenerated into a conduit for capital flight from the Club Med bloc to Germany, Luxembourg, and The Netherlands.

This ‘socialisation of risk’ is happening by stealth, a mechanical effect of the ECB’s Target2 payments system. If a political upset in France or Italy triggers an existential euro crisis over coming months, citizens from both the Eurozone’s debtor and creditor countries will discover to their horror what has been done to them.

…‘Alarm bells are starting to ring again. Our flow data is picking up serious capital flight into German safe-haven assets. It feels like the build-up to the Eurozone crisis in 2011’, said Simon Derrick from BNY Mellon.

The Target2 system is designed to adjust accounts automatically between the branches of the ECB’s family of central banks, self-correcting with each ebbs and flow. In reality it has become a cloak for chronic one-way capital outflows.

Private investors sell their holdings of Italian or Portuguese sovereign debt to the ECB at a profit, and rotate the proceeds into mutual funds in Germany or Luxembourg. ‘What it basically shows is that monetary union is slowly disintegrating despite the best efforts of Mario Draghi’, said a former ECB governor.

Professor Marcello Minenna from Milan’s Bocconi University said the implicit shift in private risk to the public sector—largely unreported in the Italian media—exposes the Italian central bank to insolvency if the euro breaks up or if Italy is forced out of monetary union. ‘Frankly, these sums are becoming unpayable’, he said.

The ECB argued for years that these Target2 imbalances were an accounting fiction that did not matter in a monetary union. Not any longer. Mario Draghi wrote a letter to Italian Euro-MPs in January warning them that the debts would have to be ‘settled in full’ if Italy left the euro and restored the lira.

This is a potent statement. Mr Draghi has written in black and white confirming that Target2 liabilities are deadly serious—as critics said all along—and revealed in a sense that Italy’s public debt is significantly higher than officially declared. The Banca d’Italia has offsetting assets but these would be heavily devalued.

Spain’s Target2 liabilities are €328 bn, almost 30pc of GDP. Portugal and Greece are both at €72 bn. All are either insolvent or dangerously close if these debts are crystallised.

Willem Buiter from Citigroup says central banks within the unfinished structure of the Eurozone are not really central banks at all. They are more like currency boards. They can go bust, and several are likely to do so. In short, they are ‘not a credible counterparty’ for the rest of the Eurosystem.

It is astonishing that the rating agencies still refuse to treat the contingent liabilities of Target2 as real debts even after the Draghi letter, and given the self-evident political risk. Perhaps they cannot do so since they are regulated by the EU authorities and are from time to time subjected to judicial harassment in countries that do not like their verdicts. Whatever the cause of such forbearance, it may come back to haunt them.

On the other side of the ledger, the German Bundesbank has built up Target2 credits of €796 bn. Luxembourg has credits of €187 bn, reflecting its role as a financial hub. This is roughly 350pc of the tiny Duchy’s GDP, and fourteen times the annual budget.

So what happens if the euro fractures? We can assume that there would be a tidal wave of capital flows long before that moment arrived, pushing the Target2 imbalances towards €1.5 trillion. Mr Buiter says the ECB would have to cut off funding lines to ‘irreparably insolvent’ central banks in order to protect itself.

The chain-reaction would begin with a southern default to the ECB, which in turn would struggle to meet its Target2 obligations to the northern bloc, if it was still a functioning institution at that point. The ECB has no sovereign entity standing behind it. It is an orphan.