1. Introduction

Cultural heritage (CH) is a complex concept that encompasses significant experiences of various types of human existence. In recent decades, the academic discourse on cultural heritage has increasingly questioned the very notion of what cultural heritage is, trying to put in balance its intrinsic and instrumental values for society (

Winter 2013;

Winter and Waterton 2013;

Social Platform for Holistic Heritage Impact Assessment (SoPHIA) Consortium 2020a). The policy-oriented literature perceives heritage both as a common asset and a shared responsibility, as well as a cornerstone of sustainable development and a way to improve people’s lives and living environments (

Council of the European Union 2014;

Council of Europe 2017;

CHCfE Consortium 2015). Recognized as a strategic resource for a sustainable Europe, cultural heritage is currently being mainstreamed beyond cultural policy into other national and European policies, thus aiming at creating added value to our society. Therefore, the practice of governing, managing, and evaluating cultural heritage have been put in the spotlight of researchers and practitioners, and issues related to CH and its relationship with society, economy, and territory have been analysed, as well as current evaluation processes needed for ensuring effective sustainable and inclusive heritage policies that include facets of heritage sustainability incorporating social, cultural, economic, and environmental aspects, thus calling for the holistic approach in evaluation of heritage projects (

Daldanise 2020;

Cerreta and Giovene di Girasole 2020;

Jelinčić and Tišma 2020;

Marchiori et al. 2021).

Preserving and using cultural heritage in a sustainable manner entails significant costs and demands financial investments. However, financial studies and feasibility analyses prepared by the public sector, which mainly disposes with such heritage, are rare and a return on financial investment is seldom expected. It is important to emphasize that financial studies and the analysis of economic evaluation alone are not enough in assessing the benefits cultural heritage sites provide to society and the local community. Thus, a broader understanding of heritage placing communities in focus and involving them in making decisions about heritage valorization have been advocated for, as well as ensuring evaluation methods that can balance the economic, social, and environmental impact of heritage (

Council of Europe 2005;

Cerreta and Giovene di Girasole 2020;

Marchiori et al. 2021).

Therefore, social management of cultural heritage is significant for the overall economic management and sustainable growth of society. This significance implies progress toward partnerships, new administrative plans, and creative business models which handle cultural heritage in a holistic manner. The tendencies recognized via the literature target social duty and socially accountable heritage administration, heritage literacy, and the general well-being of society (

Carrà 2016).

In order to ensure supportive impacts of interventions in cultural heritage on all dimensions of society,

Lingayah et al. (

1996) suggested that the purpose of cultural activities should be the starting point for measuring their outcomes, against which their effectiveness or impact can be estimated (

Lingayah et al. 1996). Identification of the most effective instruments and tools to measure the impacts of such interventions should help cultural operators, practitioners, academics, and policy-makers to establish shared quality standards that address both the creation of policies and to direct interventions.

The Europa Nostra “Cultural Heritage Counts for Europe” report (

CHCfE Consortium 2015) emphasized the relevance of a holistic approach according to the four aspects of use—social, economic, cultural, and environmental—and has introduced positive and negative impacts into the analyses of interventions, explaining the link between (policies, projects, initiatives) objectives and impact. As the impact of an intervention can be positive or negative, intended or unintended, direct or indirect, and as an observed intervention may not be the only factor contributing to the change, it is necessary to identify the cause of the observed changes as well as the project’s contribution towards the changes in question. As the practice points to the fact that the experts’ perspective mostly overrides the expertise of those who are more likely to be affected by the intervention (i.e., local stakeholders) (

Mälkki and Schmidt-Thomé 2010;

de la Torre 2002), this reinforces the Faro’s convention (

Council of Europe 2005) focusing on “the public interest associated with elements of the cultural heritage in accordance with their importance to society” (article 5). It provides a policy framework for conceptualizing cultural heritage as a common good and points to the importance of citizens’ involvement in the process of heritage valorisation and evaluation processes in the already existing impact assessment (IA) methods that measure the relationship between strategic decisions about heritage resources and change for people and their environment.

IA could be defined as a process of identifying a measurable outcome in which some heritage intervention affects certain changes in the life of a community. Therefore, impact should assume a specific form of intervention which brings up some kind of change, while the effects of such intervention can be evaluated in regard to the purpose of the intervention as well as in regard to the potential needs of benefiting the stakeholders. It represents a distinction between what would occur anyway, and what would manifest as a consequence of a certain action or intervention (

ForHeritage Project 2021;

Social Platform for Holistic Heritage Impact Assessment (SoPHIA) Consortium 2021).

By means of an evaluation process using the impact assessment tool, cultural heritage institutions can collect actionable evidence that should serve heritage institutions in reviewing their current situation, using both qualitative and quantitative methods. The literature review concerning the presently used economy-focused IA methods (

Social Platform for Holistic Heritage Impact Assessment (SoPHIA) Consortium 2020a) points to quantitative methods measuring impact that can include a cost−benefit analysis, cost− effectiveness analyses or, for example, the contingent valuation method, as well as often used qualitative methods such as the focus group method, the structured interview, expert analysis (e.g., Delphi method), policy analysis, impact value chain analysis, social impact analysis, etc.

Complementing this mainstream approach to evaluations that place the main focus on economic impact, social impact evaluation includes monitoring adjustments to people’s lifestyle, their local area, surroundings, political frameworks, individual property rights, well-being and prosperity, their concerns and goals, and other factors (

IAIA, International Association for Impact Assessment 2015). These changes can be potentially revealed both at individual and at collective levels (in a family/household, circle of friends, government agency, community/society in general) and they can be experienced in a perceptual, cognitive, or even corporeal (bodily, physical) manner (

Corvo et al. 2021).

According to

Rogers (

2014), the theory of change explains ‘impact’ as the social changes that are achieved and kept through a long time period by interacting with a given program or project (i.e., heritage intervention) as well as the changes created with other factors and conditions.

In the framework of analysing social effects of investment in cultural heritage, social impact assessment (SIA) is the most comprehensive method. In line with Frank Vanclay, SIA can be contemplated as “an umbrella or overarching framework that embodies the evaluation of all impacts on humans and on all the ways in which people and communities interact with their sociocultural, economic, and biophysical surroundings” (

Vanclay 2003, p. 7). SIA covers all aspects associated with managing social issues (

Vanclay 2019). The process assumes a wide range of different impacts relevant to cultural heritage projects such as: benefit sharing; community development, engagement and resilience; empowerment; immigration and the inclusion of the more vulnerable groups; ensuring the means of living in a modern time; acquiring local goods; project organized relocation; impacts on social life and well-being; work license; contributor commitment; determining key social effects and alleviating issues.

The definition of the suggested project (scoping);

Data collection and the establishment of a baseline approach;

The estimation and calculation of summative social outcomes;

The establishment of substitute tasks;

The creation of a mitigation policy.

Over the 50 years since its creation, SIA has continued to develop and its practice has improved over time (

Vanclay 2019). The effective implementation of SIA requires a genuine engagement of the community—that is, a meaningful interaction and dialogue in good faith, and all interested parties must be guaranteed the possibility to influence decision-making. Despite the rhetoric of independence, SIA is usually commissioned by the project proposer and thus there is certain risk concerning co-opting the impact assessment consultants; bias in the selection of identifiers to be followed; low involvement of local stakeholders; bias in selecting members of focus groups; and most importantly, bias in interpreting and analysing results, etc.

The existing methods that could qualify as holistic, cross-domain models for evaluating cultural heritage that have been proven successful are not numerous. One such model is Impacts 08, developed initially for assessment of the Liverpool European Capital of Culture, which progressively turned into the model for assessing ECoCs in general (

Phythian-Adams et al. 2008;

Garcia et al. 2010).

The Impacts 08 approach has opted for an in-depth analysis of the urban context in order to ensure adequate regeneration measures, not just for the events linked to the ECoC, but for the city as a whole in general. To do so, Impacts 08 created a holistic approach that went beyond quantitative indicators, thus making the history of the local community in the city hosting the event a crucial point of the research. The Impacts 08 evaluation procedure started almost at the beginning of the project and continued even after the ECoC’s year. A practice of planning, monitoring, and (short-term and medium-term) evaluating the expected impacts was developed within the ECoC’s program. Partnerships on local, national, and international levels were encouraged in order to build networks that will continue to live on even after the ECoC.

The literature recognizes the environmental impact assessment (EIA) for providing structure and content to a combined model known as the environmental and social impact assessment (ESIA) model, seeking to integrate EIA and SIA into a single process, which equally values social and environmental impacts. ESIA is widely applied by multilateral donors, international agencies, private and global credit institutions, and international agencies to guide decisions on financing development projects (

Dendena and Corsi 2015). Although widely used, ESIA is much less analysed in the literature than EIA. The difference between ESIA and EIA varies and depends on the definition of “environment”.

Additionally, as cultural heritage demands considerable investments for their renewal and maintenance that often surpass the budgets of owners, local communities and other interested users, the literature suggests a cost−benefit analysis (CBA) as the evaluation method quantifying the impacts of proposed cultural heritage projects on different groups within society (

Tišma et al. 2021). During the CBA implementation, qualitative methods are used as well that identify and monetarily express sociological factors.

The goal of this paper is to demonstrate how existing social impact assessment methods that we have mapped within the course of the recently completed SoPHIA project (

Social Platform for Holistic Heritage Impact Assessment (SoPHIA) Consortium 2020a,

2020b) contribute to the economic breakdown of contributions to cultural heritage while simultaneously encouraging a holistic view of the overall evaluation of heritage and the contribution of heritage to the local community. Using the snowballing approach, in which both academic sources and policy documents have been consulted, the research conducted focused on current trends, gaps, and opportunities of the current level of impact assessment identified in the field, as well as strategic and policy-relevant issues identified in the impact assessment-related literature.

Research questions were:

How are social assessment methods applicable in the analysis of the investments in cultural heritage?

What is the role of social assessment methods in the holistic view of the overall evaluation of cultural heritage in the local community?

Therefore, an increasingly important element is certainly social justification of such investments in cultural heritage. Their importance to the local community, well-being for the local population, interpretation of heritage, historical value, and the like are just some of the factors that are often overlooked. This is caused by insufficiently clear methods of evaluating social impacts, the scope of these methods, and data sources for analysis. Therefore, this paper provides an overview of methods of social impacts’ evaluation, their achievements, and possibilities of application in everyday practice for evaluating investments in the conservation and sustainable use of cultural heritage. Besides the literature overview of available methods for social assessment, it also points to a set of interdisciplinary indicators by which such impacts can be evaluated. Specifically, the paper explores social impact assessment as a methodological tool contribution in economic analysis of investments in cultural heritage. Next, we present two case studies in the Republic of Croatia: the social evaluation management plan for the old town of Buzet and Ivana’s House of Fairy Tales will be used as a test bed for the proposed social impact methods, thus providing analytical examples for the provided outcome analysis, closing comments, and suggestions for future research.

2. Materials and Methods

A qualitative methodology combined with an abductive approach was used to study social assessment methods in an economic analysis of investment in cultural heritage. Logical reasoning in this research is non-deductive, with an abductive mode of argument, because the research was guided by both the extant literature and collected data. A review of the literature on social assessment methods was conducted, including published scientific papers, conference and workshop reports, current legal documents and strategic policies, authorized statistical data, and online materials. On one hand, research results were carried out by moving from a special case to general principles. The bottom-up research approach with an inductive method was used through gathering evidence, seeking patterns, and forming conclusions. The research was conducted with observations that are specific and limited in scope. The scope of analysed methods was related to social impacts assessment, their achievements, and possibilities of application in everyday practice for evaluation of financial contributions to maintainable use of cultural heritage and its conservation (

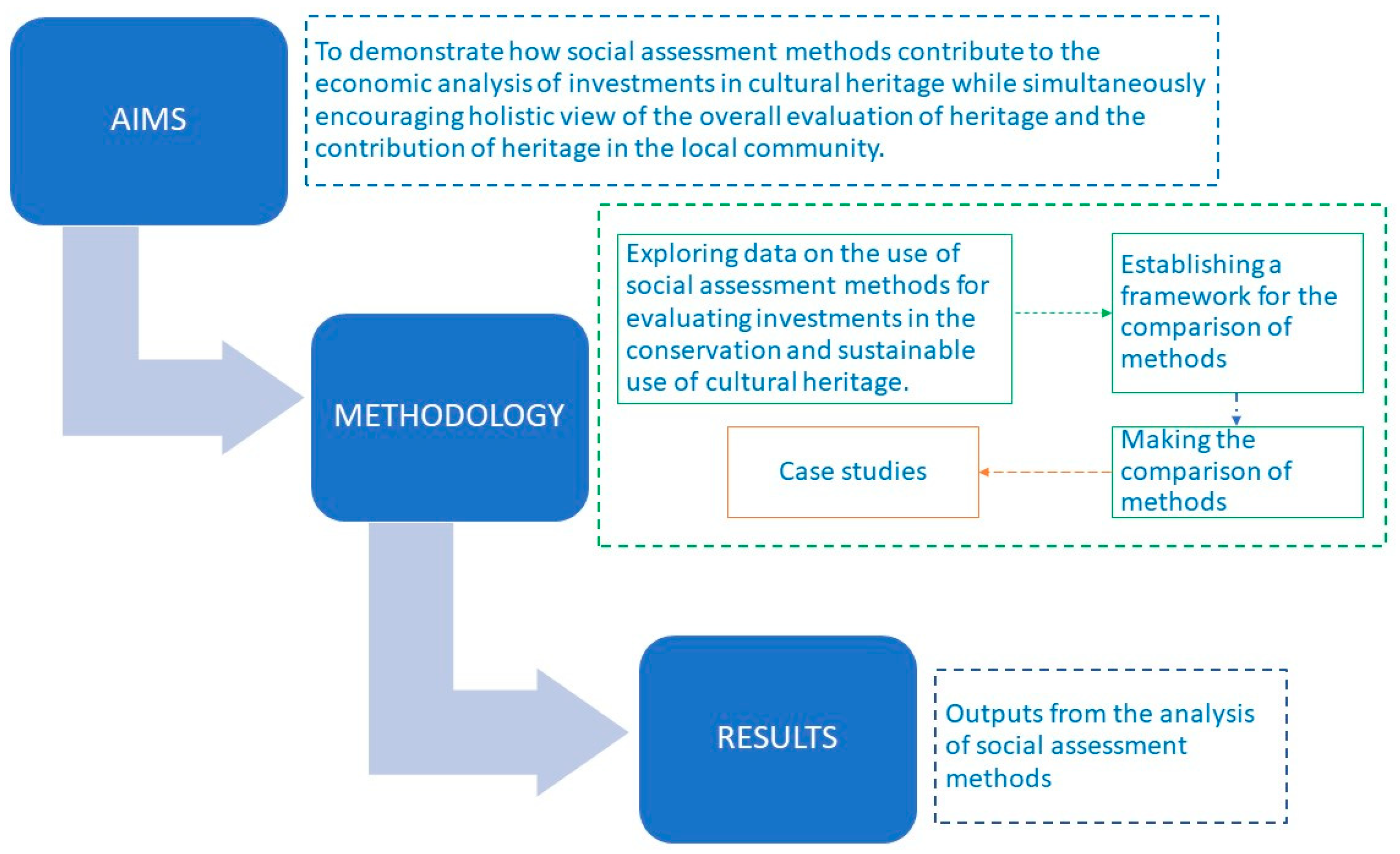

Figure 1 and

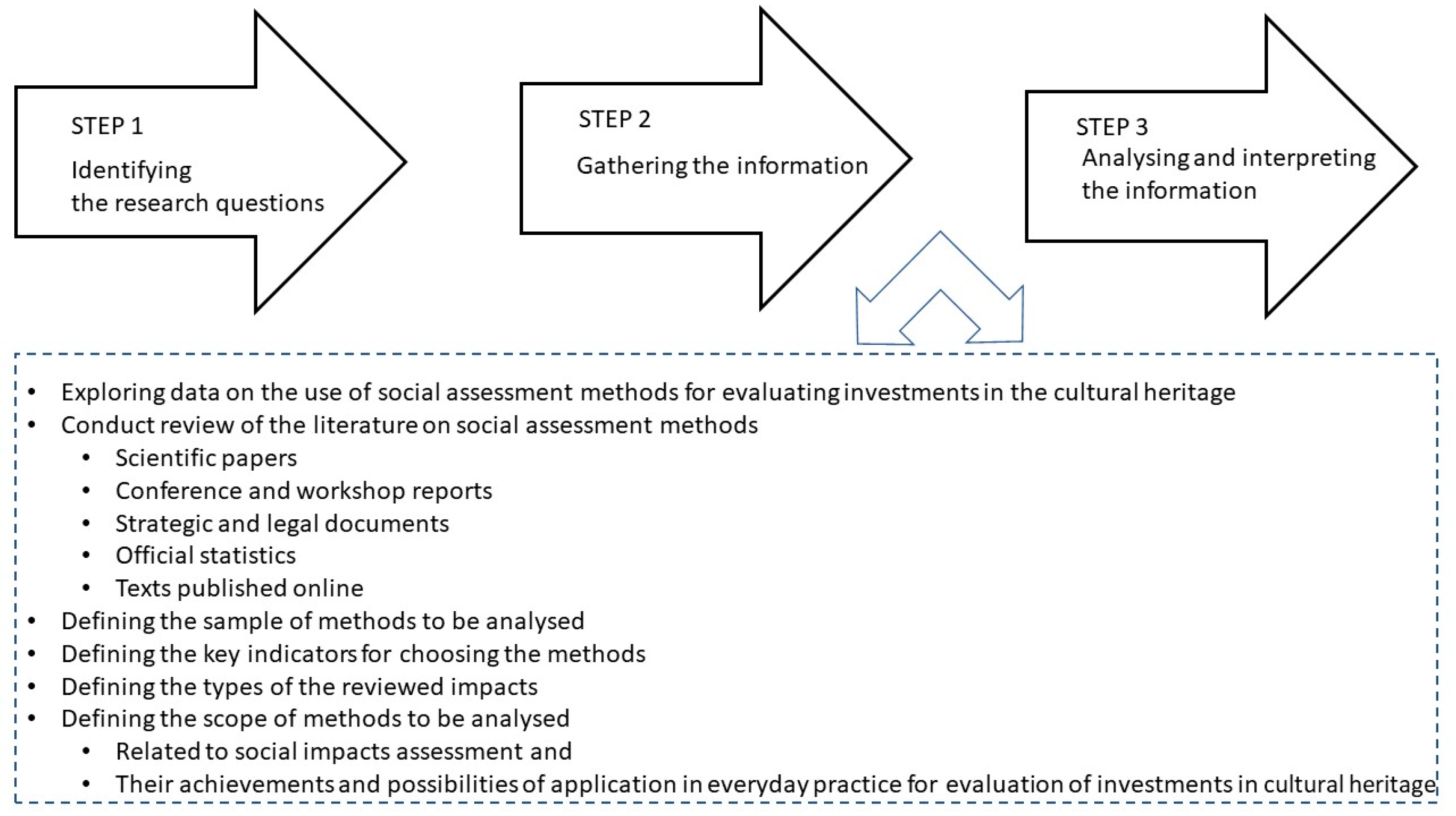

Figure 2). On the other hand, the abductive approach was used in the case studies of Ivana’s House of Fairy Tales and the Town of Buzet, while probable conclusions were made from the analysis of only the data that could be accessed because a minor part of evidence was not known.

Figure 1 shows the research process flow, which began with setting the research objectives, defining the research methodology, and planning the analysis of obtained results. The focus was on the role of social methods in the evaluation of investments in cultural heritage as part of a holistic approach to the overall evaluation of financial support to cultural heritage. For this purpose, research related to the use of social methods was conducted, and then a framework for their comparison was established, according to which the methods were compared. The results of the comparison of the methods enabled carrying out their practical application in the assessment of cultural heritage, which was shown through the case studies, rounding off the overall image of the research results and carrying out their analysis.

Figure 2 shows detailed steps in the research process, from identifying the research problem the research was conducted for, to gathering data, and their analysis and interpretation.

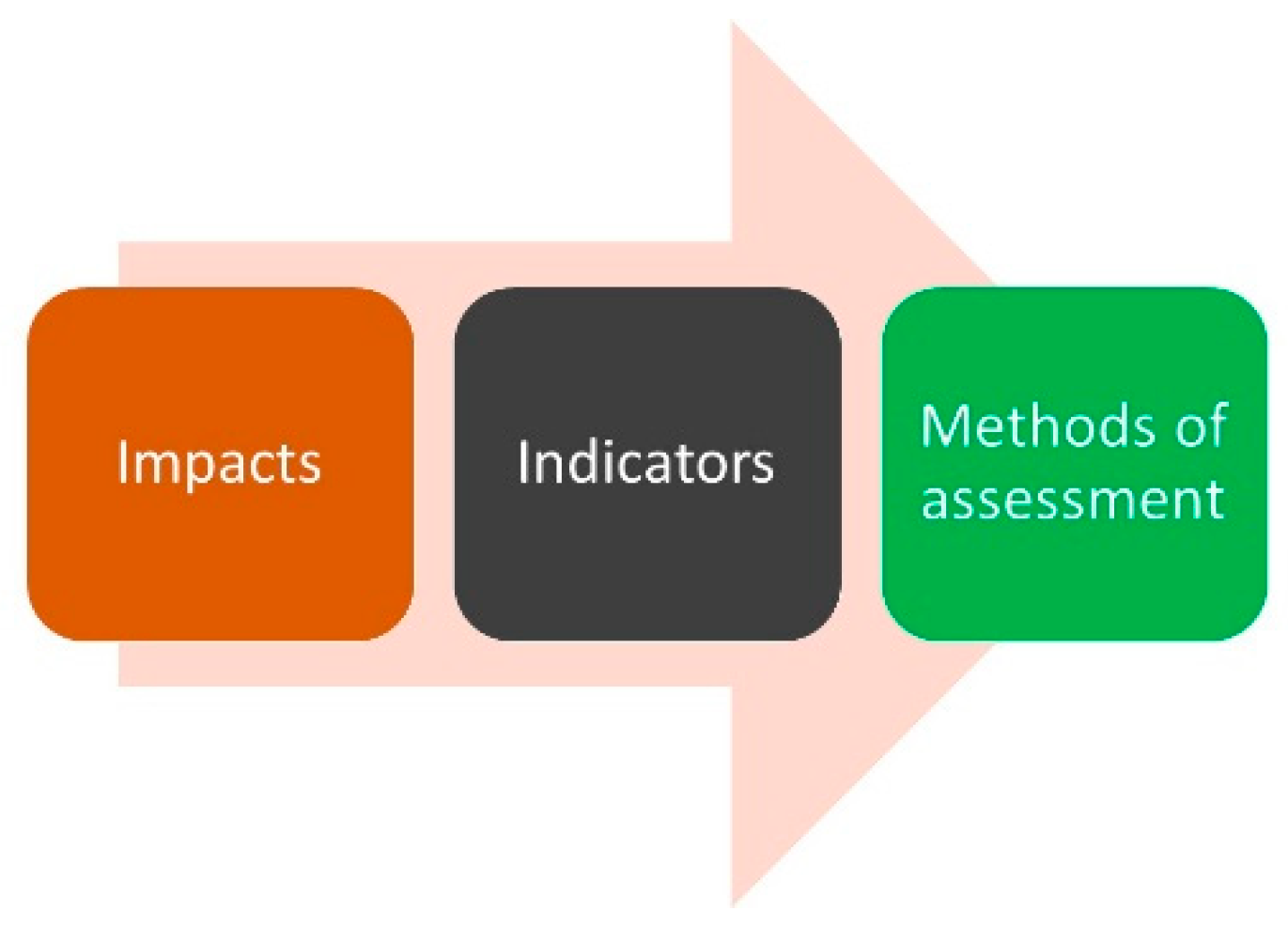

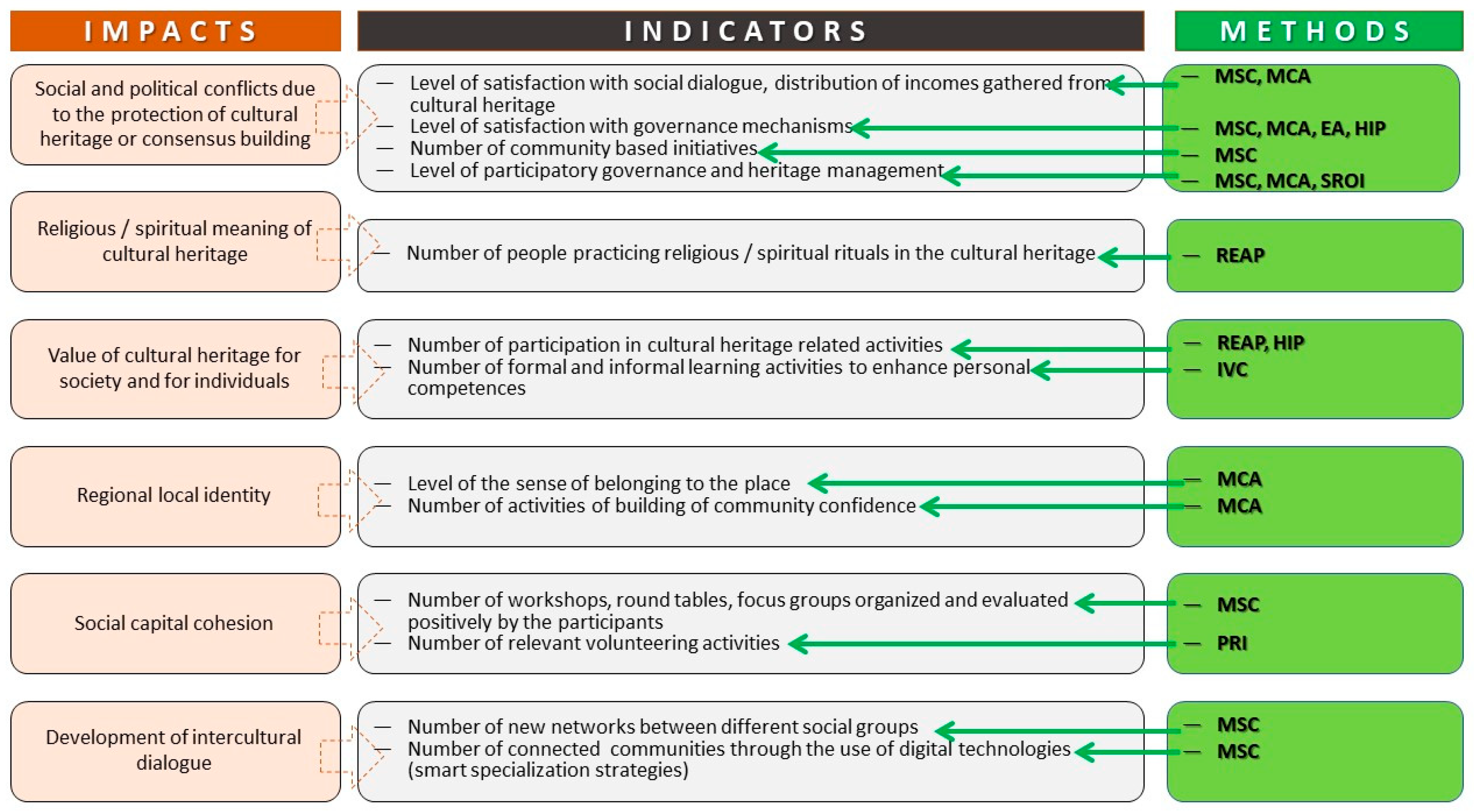

Research and analysis were conducted on a sample of twenty methods selected by a team of experts according to their impact on projects or cultural heritage interventions (

Figure 3). Impact assessment methods have been previously studied by a wider team of 34 international team members, which the authors of this article have been participating in, within the EU-funded SoPHIA project dealing with heritage impact assessment. The types of the reviewed impacts were: social and political conflicts due to the protection of cultural heritage or consensus building; religious and spiritual meaning of cultural heritage; benefit of cultural heritage to the community and individuals; regional and local identity; and social capital cohesion. Furthermore, selected methods were compared according to type (purely quantitative, purely qualitative, or mixed), due to assessment tools such as narratives, stories, cases, indicators, physical data comparisons, standards and benchmarks; due to outputs (reports, indexes, rankings, maps); due to actors and governance (participatory, technical); due to way they work; due to relevant examples of application, due to benefits and shortcomings. In order to find methods convenient for the assessment of impacts on cultural heritage, the authors included: social and economic impact assessment (SEIA); environmental and social impact assessment (ESIA); heritage impact assessment (HIA); and Impacts 08. SWOT analysis was used to identify gaps and opportunities. These methods were selected as they correspond to the nature of heritage values and are in line with the case studies selected.

Possibilities to use broader social impact assessment in the evaluation of cultural heritage are presented through two case studies in the Republic of Croatia: the implementation of the social evaluation management plan for the old town of Buzet and the evaluation of social effects of investing in Ivana’s House of Fairy Tales. The contributions of the methodological tools used and social impact assessments in the evaluation of cultural heritage interventions were investigated. Suggestions were prepared for various decision-makers on the usefulness of such broader methods.

The following documentation has been collected and analysed: the preliminary assessment of the Integrated Built Heritage Revitalization Plan (IBHRP), documents related to the strategic development of the City of Buzet, as well as media materials and articles. All documents were provided by the city administration but are also available online (e.g.,

https://www.interreg-central.eu/Content.Node/T2.4.4-IBHRP-Buzet.pdf, accessed on 3 July 2022).

Available strategic documents were analysed for Ivana’s House of Fairy Tales, i.e., (i) strategic development documents and plans on the local level, and the (ii) strategic development document for Ivana’s House of Fairy Tales with the accompanying action plan for the 2014–2020 period.

The available statistical data from the Croatian Bureau of Statistics as well as the data collected and monitored on a regular basis by the cities of Buzet and Ogulin and their tourist boards were collected for both case studies. These are mainly data related to demographic trends, economic growth, entrepreneurial activities, investments into cultural heritage, tourist visits, and the like. The key challenge of this exercise was the fact that the data were mainly monitored at the level of local government units of the cities of Buzet and Ogulin and that they can only partially be related to the case studies themselves.

Thus, most of available indicators were qualitative indicators representing a strong stakeholders’ perspective and collected by the survey method. Qualitative indicators of the collected surveys relate to social impacts, availability analysis of such indicators, and the scientific basis of collected answers. Qualitative indicators were collected through the interviews, but also through the book of impressions of the visitors and through the visitors’ impressions shared with a wider public on online platforms during the years while the project was being implemented.

3. Results

3.1. Comparative Overview of Social Assessment Methods for Evaluating Investments in Cultural Heritage and Their Role in Holistic View of the Overall Evaluation of Cultural Heritage in Local Community

The group of most used social assessment methods includes: contingent valuation method (CVM), cost–benefit analysis (CBA), cultural impact assessment (CIA), environmental impact assessment (EIA), environmental and social impact assessment (ESIA), expert analysis (EA), G4 guidelines, heritage impact assessment (HIA), Impacts 08, impact value chain (IVC), life cycle assessment (LCA), most significant change (MSC), multi-criteria analysis (MCA), policy analysis, principles for responsible investment (PRI), rapid ethnographic assessment procedure (REAP), social impact assessment (SIA), social return on investments (SROI) and (SEIA) (

Table 1).

Holistically looking, the importance of these methods lies in their ability to support a deeper understanding of the social environment. The assessment methods highlight potential environmental impacts and contribute to minimizing harmful effects while maximizing possible benefits. Furthermore, the results produced by these methods can be combined with the economic analysis of investments in cultural heritage. This will assist cultural operators, practitioners, academics, and policy-makers in decision-making and policy establishment (

Social Platform for Holistic Heritage Impact Assessment (SoPHIA) Consortium 2021). The common characteristic of these methods is a proactive approach with a focus on conducting a structured assessment while remaining as objective as possible. The development of alternatives is always considered, and an effort is made to efficiently produce a clear, concise, and unbiased impact assessment, while simultaneously involving the public whenever possible. These methods are critical in planning and decision-making processes.

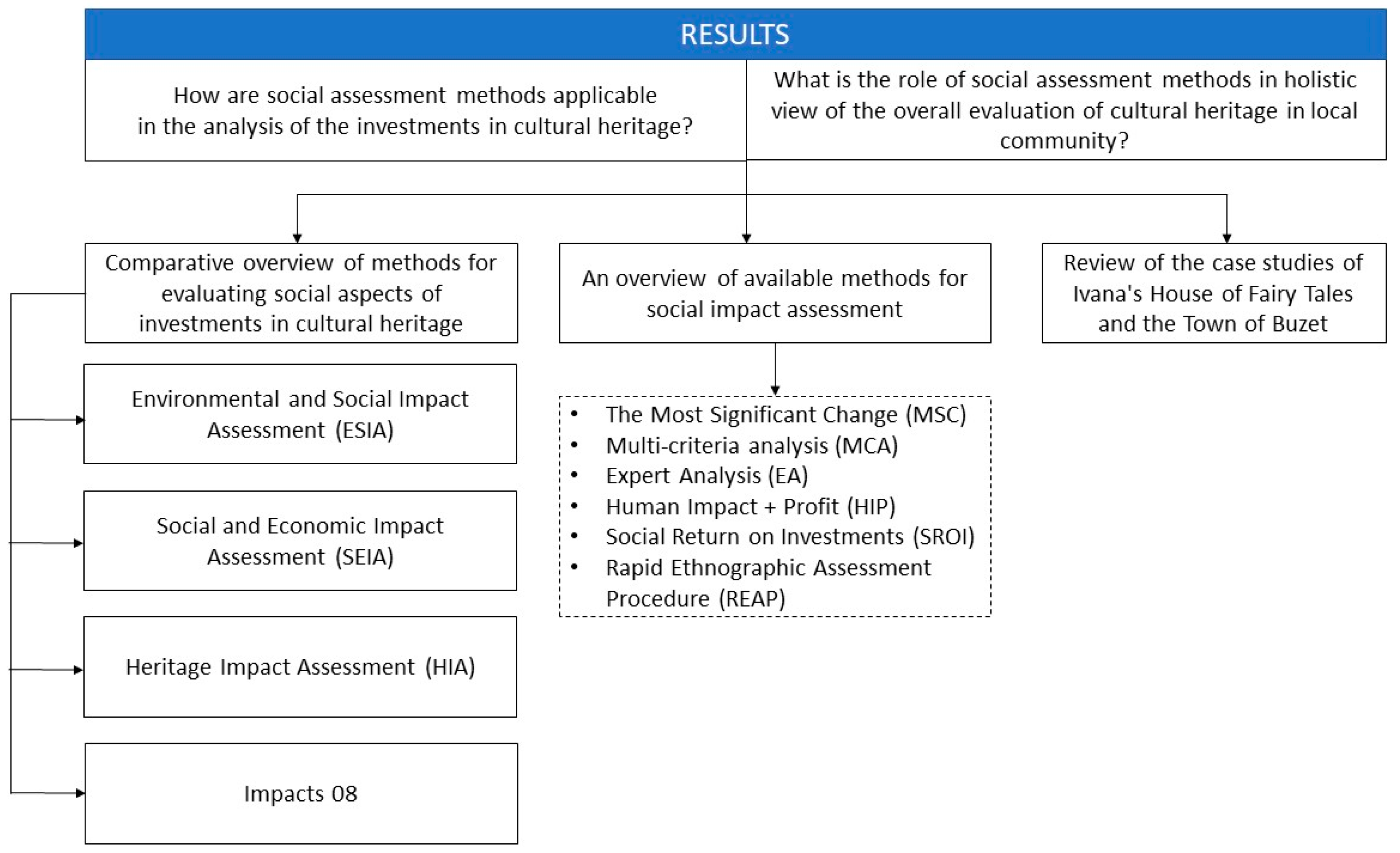

The path demonstrating research results is shown in

Figure 4.

3.1.1. Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA)

The main objectives of ESIA is to establish a strong understanding of the existing environment and social environment, identify potential impacts on the environment, as well as on local communities, ensuring the model, application, process, and the following withdrawal of development are applied with minimal harmful impacts on the area and society while maximizing potential benefits (

WBCSD 2015). The approach is in line with the principle of sustainable development, as set out at the UN Conference on Environment and Development (

UNCED 1992) and the International Finance Corporation (IFC) execution norms on environmental and communal sustainability: the evaluation and management of natural and social risks and effects; working conditions; asset effectiveness and contamination prevention; well-being and security; land procurement and compulsory relocation; biodiversity protection and sustainable management of living natural assets; native residents and social legacy (

International Finance Corporation 2012).

ESIA appears to be a potentially powerful tool founded on a combined multiple impact evaluation of projects, programs, and standard practice development. The entire ESIA process includes seven key elements of the process: review and evaluation scoping; examination of potential substitutes; finding interested parties and gathering of benchmark statistics; effect identification and evaluation; creation of activities and measures; the importance of effects and assessment of remaining impacts, and finally documenting the whole process (

Therivel and Wood 2017).

The method is characterized by early involvement of all stakeholders, leading to increased stakeholder commitment, and increased transparency and accountability. Furthermore, it is represented by responding to the need to capture complex and strong mutual relations connecting the land and society. It is also known for providing opportunities to measure and manage local conflicts. Early involvement of all stakeholders leads to higher levels of ownership and engagement in the process (

Mitchell et al. 1997). There are, however, potential risks for later objections during planning applications.

3.1.2. Social and Economic Impact Assessment (SEIA)

A similar combined assessment model identified during the literature review research is the social and economic impact assessment (SEIA) model. SEIA is “a useful tool to help understand the potential range of impacts of a proposed change, and the likely responses of those impacted if the change occurs” (

Australian Government Department of the Environment and Heritage 2005, p. 5). It assesses impacts of a variety of change categories, and therefore it applies to some extent to the environmental domain (

Australian Government Department of the Environment and Heritage 2005). SEIA uses appropriate indicators to assess the impacts and proposes appropriate methods for data collection. It can help in designing strategies to avoid negative effects, so as to minimize adverse effects, and maximise benefits of any alteration (

Australian Government Department of the Environment and Heritage 2005). SEIA provides many opportunities for stakeholder engagement. Although it can be performed as a purely technical assessment that does not involve the community, the inclusion of stakeholders’ views holds great benefits throughout the whole SEIA.

Albeit the specific tools used in each SEIA can differ, they for the most part include some or the entirety of the following stages (

Taylor et al. 1990): scoping the environment and limits of the effect evaluation; profiling present effects of the action being inspected, incorporating the historical context or present setting; developing substitutes, in which different ‘impact’ situations are created; predicting and assessing the impact of various resulting scenarios; observing real impacts; avoiding and responding to unwanted effects; review of the impact evaluation process.

The socioeconomic impact assessment evaluates the socioeconomic cost in relation to the socioeconomic benefit. An integrated methodology can give an extensive and practical outcome, providing data on possible financial impacts, as well as on significant social qualities connected to the operation that provides information on likely views and answers to the proposed change. The challenge, however, is to address potential data collection difficulties in order to comprehensively cover relevant issues.

3.1.3. Heritage Impact Assessment (HIA)

Heritage impact assessment (HIA) is a widely accepted methodology at international level in urban and infrastructure areas. It is used to evaluate the effect of territorial or infrastructural advancement of projects on world cultural heritage sites. UNESCO and ICOMOS use HIA as a means for preventing harmful impacts on cultural heritage of outstanding universal value (OUV) (

UNESCO 2011;

ICOMOS 2011).

Actually, HIA is a statement or document depicting the historical or archaeological significance of a building or landscape within a wider environment. It is used to protect legacy sites from harmful effects caused by suggested projects, and to propose effective mitigation plans to ensure balance and stability in combining conservation and development. The process follows the application of a 9-point scoring severity rating of the impacts caused by development on the site.

HIA’s strength is in a strong focus on procedure. In addition, it increases objectivity in relation to individual assessments and provides long-term improvements (

Patiwael et al. 2019).

However, there are some objections that HIA is neither directly related to OUV attributes nor objective. Moreover, heritage impact assessments’ increased budgetary and time requirements can be an obstacle to their implementation.

3.1.4. Impacts 08

The Impacts 08 approach engaged in the issues left out in many assessments concerning the ‘soft indicators,’ such as online networking platforms and individual stories, using a multi-method, longitudinal analysis of news portals, personal interviews, targeted surveys, and focus groups representing the community (

Phythian-Adams et al. 2008;

Garcia et al. 2010). Furthermore, the opinions of residents took the central place in the analysis, thus also taking into account both desirable and non-desirable effects. The method focused mainly on five areas: cultural access and engagement; finances and travel; cultural resonance and preservation; impressions and understanding; administration and delivery methods.

These objectives also agree with the European Commission recommendations on the ECoC outputs. However, there were also some shortcomings. Impacts 08 analysis cannot foresee the way the situation would develop in the case that the ECoC’s benefits were only temporary. Sustainable development should also receive more attention. The role of visitors and tourism is crucial in the evaluation process. However, it is important to avoid focusing entirely on them in order to provide a real holistic approach. Accordingly, there was no direct mention of environmental repercussions in the report, and it dwelled mostly on well-being, and environmentally related key issues. A report on realistic impact assessment of the method demands wise choice and a set of objectives. Choosing so-called “easy wins” or unachievable goals could be compromising for the evaluation procedure.

A holistic approach created by Impacts 08 exceeded quantitative indicators and made the actual lived residents’ experiences in the event host city a key point of its research. The impact of culture-led regeneration programs was also measured, aiming to ensure the city’s positive repositioning on national and international levels; to recognize the impact humanities and culture have on improving the living standard and appeal of cities; to create long-term development and durability for the city cultural sector; to encourage more visitors, and, finally, to encourage and increase participation in cultural activities (

Phythian-Adams et al. 2008;

Garcia et al. 2010).

3.2. Research Analysis of Available Methods for Social Impact Assessment

Results on the most used methods for social impact assessment were structured according to their impact on project or cultural heritage intervention (

Figure 2). As previously mentioned, the types of reviewed impacts were: social and political conflicts due to the protection of cultural heritage or consensus building; religious and spiritual meaning of cultural heritage; worth of cultural heritage for the community; regional and local identity; and social capital cohesion.

The observed methods were analysed according to the areas of impact (spot, local, regional, sectoral); type (quantitative, qualitative, mixed); main assessment tools (narratives, stories, cases, indicators, physical data, economic data, comparisons, standards, benchmarks); information sources (internal, external, third parties, independent); outputs (reports, indexes, rankings, maps); actors and governance (participatory, technical); benefits and shortcomings.

The research results showed that the best methods of assessment for the impact categorized as social and political conflicts associated with the preservation of cultural heritage or consensus building were:

The most significant change (MSC) and the multi-criteria analysis (MCA) according to the indicator identified as the level of satisfaction with social dialogue and distribution of incomes gathered from cultural heritage;

The most significant change (MSC), the multi-criteria analysis (MCA), the expert analysis (EA) and human impact and profit (HIP) scorecard according to the indicator identified as level of satisfaction with governance mechanisms;

The most significant change (MSC) according to the indicator identified as the number of community-based initiatives;

The most significant change (MSC), the multi-criteria analysis (MCA), and social return on investments (SROI) according to the indicator identified as level of participatory governance and heritage management.

The most appropriate method of assessment for the impact of religious and spiritual meaning of cultural heritage was the rapid ethnographic assessment procedure (REAP) using the indicator number of people practicing religious and spiritual rituals in the cultural heritage.

In addition, the methods rapid ethnographic assessment procedure (REAP), human impact and profit (HIP) scorecard, and impact value chain (IVC) were recognized as best in evaluating cultural heritage for society and individuals by using the following indicators: number of participations in cultural heritage related activities and number of formal and informal learning activities to enhance personal competences.

Furthermore, the indicators’ level of the sense of belonging to the place and number of activities of building of community confidence established the method multi-criteria analysis (MCA) as the most appropriate for the impact of regional local identity.

The impact of social capital cohesion was best valued with the methods most significant change (MSC) and the principles for responsible investment (PRI) by means of the following indicators: the number of workshops, round tables, and focus groups organized and evaluated positively by the participants and the number of relevant volunteering activities.

The most suitable method according to the indicators the number of new networks between different social groups and the number of connected communities through the use of digital technologies (smart specialization strategies) for the impact named development of intercultural dialogue was the most significant change (MSC) (

Figure 5).

The MSC method was more suitable to some application contexts than other methods. In an easy application with easily defined effects, quantitative monitoring might also be sufficient and would in reality be much less time-intensive than MSC.

In the case of using the MCA method, each indicator must be supported through one or more measures, matching the proof base for scoring that indicator. Ideally, these are quantifiable measurements. By the nature of the MCA method, a few will involve qualitative evaluation of how directly preferences influence elements of the indicators and objectives (

Australian Government, Infrastructure Australia 2021).

The HIP was recognized as the “best hope” in terms of a strategy that can methodically reveal the interrelationship between affect and profitability, which financial specialists recognized as a high concern.

The SROI is a combined (qualitative and quantitative) method that gives data specifically focused on the social value and provides roundabout experiences on financial and environmental impacts. As it is based on the theory of change, the relationship between inputs or resources is well clarified and this situation leads to a better deployment of activities and their final results (

Nicholls et al. 2009).

The REAP method is mainly a qualitative lookup approach focusing on the collection and evaluation of regionally applicable data. This method evokes wealthy, descriptive data that contributes to discovering why an issue or a circumstance may be happening and how to respond in the best way (

Sangaramoorthy and Kroeger 2020).

Results of the SWOT analysis showed the trends in evaluating cultural heritage: involvement of a wide group of stakeholders in valorisation, preservation, management; long-term heritage policy (evidence-based and society-based); new management schemes and innovative business models; shift from a preservation-focused (object-oriented) approach to a value-focused (subject-oriented) approach; to design cultural development strategies to boost local and regional competitions and comparative advantage; local and regional authorities should actively take part in the management of potential that cultural heritage has; defining quality in relation to interventions on cultural heritage (cultural diversity, inclusion, intangible heritage, sense-of-belonging); community-based values; capacity of cultural heritage to connect social groups.

Identified gaps and opportunities are: hard to evaluate social impact; promoting volunteering activities; use of digital technology—impact on smart specialization strategies; cultural heritage potentializing strategic resource for Europe; cross-sectoral impact and heritage—primarily social resource.

3.3. Review of the Case Studies of Ivana’s House of Fairy Tales and the Town of Buzet

The possibility to evaluate the social impact of cultural heritage is presented in the paper through two case studies conducted in the Republic of Croatia of heritage that is locally and regionally important, and can significantly boost local development: the implementation of social evaluation management plan for the old town of Buzet—Integrated Built Heritage Revitalization Plan of the Buzet Historic Town Centre (IBHRP) and the evaluation of social effects of investing in Ivana’s House of Fairy Tales (IKB/IHF) in the city of Ogulin. The analysed cases differ by their type and nature. While Ivana’s House of Fairy Tales is a cultural institution, the other case refers to the urban complex of the Buzet old town core, a location for residents to live and work.

IBHRP is the development plan of the old town core of the city of Buzet, an old hilltop settlement, one of the largest and historically most important towns in the region of Central Istria, Croatia. Its implementation is envisaged for the 2017–2025 period. Thus, the analysis provides a mid-term assessment. The old town of Buzet is of crucial importance to the recognizability and visibility of the city of Buzet. The EU partially finances its restoration activities.

Ivana’s House of Fairy Tales (IHF) is an investment project supported by the European Regional Development Fund, the Central Finance and Contracting Agency for EU Programs and Projects Zagreb, the Ministry of Culture of Croatia, the City of Ogulin, and the Tourist Board of the city of Ogulin. Its goal was to create a brand of the city of Ogulin, based on the intangible heritage focusing on fairy tales. This was envisaged through developing of the visitor centre; i.e., a museum based on stories and fairy tales of the famous Croatian author Ivana Brlić-Mažuranić. IHF was opened in 2013. The centre’s development strategy for 2013–2020 was prepared. The strategy’s implementation was tested in an evaluation after the implementation of the strategic plan of IHF.

The key topics of impact assessment in each case included: social capital, sense of place, well-being/quality of life, knowledge, strong EU and global partnerships, prosperity, attractiveness, protection, and innovation.

The IHF case study is an important example of the way local history can be a generator for a city’s infrastructural and tourism development, as it shows that the visitor centre completed the vision of Ogulin as a fairy tale town, forming a feeling of fellowship and distinctiveness among its residents. The attractiveness of the town was increased, both as a dwelling place and as an important destination of cultural tourism.

By developing IHF, it was expected that the brand ‘Ogulin—Homeland of Fairy Tales’ would bring a significant added value to the promotion of Ogulin’s intangible cultural heritage and would position Ogulin as a desirable experience destination; increasing tourism sector profits through a favourable environment for entrepreneurial activities and tourism products development as well as creating new jobs. The branding strategy also intended to increase brand presentation innovation as well as business excellence application. The establishment of Ivana’s House of Fairy Tales has proved to be a great contribution to the touristic and cultural value of the town of Ogulin, making it an attractive and distinct cultural tourism destination. It also showed the way of designing a project in order to integrate it into a wider context of the town of Ogulin’s development.

The Ivana’s House of Fairy Tales’ evaluation highlights the importance of cultural intervention and strategic planning in raising a town’s prosperity, while simultaneously raising a sense of pride and ownership of heritage among the residents of the town.

The topic of social capital is also significant in the case of Ivana’s House of Fairy Tales. The IHF evaluation showed the close relationship of the two evaluated areas—access and inclusion. Their deeper analysis should provide the answer to the question concerning the access-enabling tools for different social groups of visitors. The analysis showed that the visitor centre caters fully to persons with disabilities—having a built-in elevator for those with moving difficulties, interactive audio exhibits for blind and visually impaired persons, while persons with hearing disabilities can experience the exhibition through video exhibits and a rich visual content. All these facilities increase the social inclusion of persons with disabilities. Another benefit for persons with disabilities and difficulties is their entrance fee exemption. Thus, openness to all kinds of visitors significantly contributes to the project’s social and geographic accessibility.

The second example analysed is an intervention into urban cultural heritage that affects urban communities, and living and working spaces and cohabitation—the historic town of Buzet and the Integrated Revitalization Plan of the Buzet Historic Town Centre (IBHRP). In 2015, the city of Buzet prepared the “Development Strategy of the City of Buzet for the 2016–2020 period”, recognizing the quality of residents’ life, the importance of protecting natural and cultural heritage and increasing competitiveness of the economy as its main principles and values. Those values were the foundation of the City of Buzet’s vision as a modern city of satisfied people, with a competitive economy, attractive natural and cultural heritage, and its sustainable development stemming from traditional values. While drafting the development strategy, the local administration recognized the town’s development potential and in 2017 the Integrated Revitalization Plan of the Buzet Historic Town Centre (IBHRP) was drafted for the 2017–2025 period. The development of the IBHRP plan included both the employees of the town administration and the residents of Buzet—those residing both in the old town or in the surrounding settlements. This case study emphasized an overlapping of the issues across the evaluation themes; i.e., access, social cohesion, engagement, participation, (local/participatory) governance (and networking).

Buzet’s case shows interrelation between cultural heritage and viable growth and the importance of the process of involving different stakeholders and balancing their diverse opinions and objectives, while working towards a common vision—which in Buzet’s case was to improve the town residents’ lives, and simultaneously to turn Buzet into an attractive location for entrepreneurs and tourists. The agreed vision was based on two pillars; (a) environmental, social and economic sustainability, and (b) tourist attractiveness (

Ariza-Montes et al. 2021). Eighteen interconnected programs were planned for its implementation. The case study of Buzet revealed the complexities of achieving a balance between the needs of the tourism industry while at the same time bearing in mind Buzet’s historical centre’s function as a living site intended for the life and work of its residents.

Buzet’s old town core, situated on the top of a hill surrounded with vegetation, is inaccessible by public transport. This makes it difficult to access for persons with disabilities, being possibly an exclusionary obstacle to them. The lack of public transport and parking lots are infrastructure issue and are a challenge to the site’s quality of services, which relates both to well-being and quality of life issues, but also to the issues of Buzet’s accessibility and its tourist attractiveness. Quality of life improvement efforts through planned infrastructure developments (including cultural heritage properties’ renewal through renovations, tourists’ accommodation facilities that generate income) provide a positive contribution to prosperity and the livelihood of Buzet’s residents. Nevertheless, the issues concerning access to the site remain an important problem to be solved, as this issue in the urban context concerns issues of social inclusion, well-being and standard of living, and relate to the value of service issues. The lack of public transport and parking lots issue is recognized by the IBHRP, but so far this problem has not been solved.

Through the analysis of the proposed topics of social impact assessment, social capital, sense of place, well-being/quality of life, knowledge, strong EU and global partnerships, prosperity, attractiveness, protection and innovation, project leaders recognized the full potential for the projects analysed and possible avenues of their future development, also recognizing the problems that will be discussed further in the article.

4. Discussion

Some issues that emerged referring to the social domain impact evaluation were: the difference between expert values or knowledge, and the peoples’ everyday perspective on local and regional environments; the perception and valuation by various stakeholders, not least the public, of urban and regional environments as cultural heritage from their own perspectives should be considered; ensure that the diversity of tools matches the diversity of values identified; choosing experts and professionals able to understand and accept the methodologies and viewpoints of others; incomplete governance frameworks; inflexible rules for protection; insufficient capacity building; deficits in data and lack of concrete measures.

The testing of the assessment process on the examples of the IBHRP for the Buzet Old Town and of the establishment of the visitor centre for Ivana’s House of Fairy Tales was a challenging task. The challenges concerned a lack of quantitative data (expressed as a low score in

Table 2), and, in cases where data sources were available, the challenge lay in the impossibility of separating the impacts of the implemented activities of the analysed cases from the wider context. For example, there were no data sources that would allow us to separate impact of the activities in the old town from the development indicators of the entire city of Buzet. The Old Town of Buzet, a historical urban inhabited neighbourhood, can be visited free of charge, which makes it impossible to monitor the exact number of visits. The statistical data were available on the level of entire town, and not for the old town neighbourhood in particular, thus making impossible precise assessment of individual variables in the model by means of secondary data—e.g., the number of visitors, employment data, investments in culture, tourism, etc. (

Table 2). The challenging issues in cultural heritage evaluation are marked as having a low, medium, or high score according to expert judgement. A low score for the challenging issues in

Table 1 means that there is a crucial limitation in the social domain impact evaluation, such as lack of quantitative data. A medium score indicates that the observed data issues significantly affect social impact analysis. Issues with a high score reflect the importance of their role in the assessment of social capital.

Including the interested parties in the social impact analysis for cultural heritage investments was very important, considering that stakeholders were the source of data one cannot find in statistical databases, the budget of the City of Buzet analysis and other available data. However, it is quite clear that it is not enough to rely predominantly on stakeholders’ insights, without any supporting data. Such an approach could be exposed to subjective interpretations—either over- or under-emphasizing certain elements in the project (

Table 2).

The evaluation of the visitor centre for Ivana’s House of Fairy Tales met fewer challenges and difficulties than was the case of the IBHRP. The stakeholders considered the model appropriate for the IHF evaluation. Indicators were also considered suitable and relevant for the IHF, particularly the indicators concerning the themes of: social capital, sense of place, well-being/quality of life, knowledge, prosperity and attractiveness. However, data for some indicators were publicly available and relatively easy to find, while finding data for other indicators was more challenging. Besides quantitative data, in the evaluation of the IHF visitor centre, qualitative data were obtained through interviews with the stakeholders, confirming the findings of the quantitative data analysis. This analysis was performed seven years after the beginning of the project, thus the interviewed stakeholders referred to the successful impact the project had on the local community in that period. The success was linked to the growing number of local visitors and tourists visiting Ogulin, thus contributing to its prosperity, including raising the sentiment of pride and belonging in the local community. Therefore, the stakeholders considered the project as having long-term positive effects on the economy and community development in Ogulin (

Table 2).

The applicability of the social assessment methods in the assessment of social capital is considered to be high. The theme of social capital encouraged the stakeholders to consider the development of new models of planning and management through participative planning and good governance. Thus, in this particular case, the model was quite educational for the project stakeholders who examined it (

Table 2).

5. Conclusions

There are not many scientific articles and literature reviews exploring availability of methods for cultural heritage investment assessment from the aspect of the impacts of those investments on local community. Additionally, there is a lack of research regarding the applicability and usability of analytic methods for social evaluation of cultural heritage. Therefore, this paper points to the insufficient exploration of the issue, at the same time pointing to the potential of different sociological methods that can be used to analyse events and changes occurring due to investments in cultural heritage in communities. Besides the overview of the available methods, examples were provided of two pilot projects—Ivana’s House of Fairy Tales in Ogulin and the Integrated Built Heritage Revitalization Plan in the City of Buzet.

These examples pointed to the role and importance of cultural heritage assessment for the local communities. It has been proved that social assessment methods strongly contribute to the economic analysis of investments in cultural heritage, simultaneously encouraging a holistic view of the overall evaluation of heritage and its contribution to the local community.

The best proposed methods of assessment for the impact categorized as social and political conflicts arising from cultural heritage preservation and consensus-building were: the most significant change (MSC) and the multi-criteria analysis (MCA) according to the indicators identified as level of satisfaction with social dialogue, and distribution of incomes gathered from cultural heritage; the most significant change (MSC), the multi-criteria analysis (MCA), the expert analysis (EA), and human impact and profit (HIP) scorecard according to the indicator identified as level of satisfaction with governance mechanisms; the most significant change (MSC) according to the indicator identified as the number of community-based initiatives; and the most significant change (MSC), the multi-criteria analysis (MCA), and social return on investments (SROI) according to the indicator identified as level of participatory governance and heritage management.

The most appropriate method of assessment for the impact religious and spiritual meaning of cultural heritage was the rapid ethnographic assessment procedure (REAP) using the indicator the number of people practicing religious and spiritual rituals in cultural heritage.

The methods rapid ethnographic assessment procedure (REAP), human impact and profit (HIP) scorecard, and impact value chain (IVC) were shown to be the best in assessing the value of the impact of cultural heritage for society and individuals. The principles for responsible investment (PRI) was best suited to assessing the impact of social capital cohesion.

When observing the aspect of social assessment methods in both case studies (Ivana’s House of Fairy Tales and the Town of Buzet), it could be concluded that in developing future projects and programs of this type, it would be important to clearly accentuate key indicators and the obligation of regular data collecting. In this way, the sustainability of investment in cultural heritage over time could be clearly shown, whether it is the matter of ex ante, ex post, or the longitudinal dimension.

The main identified trends in evaluating cultural heritage were:

Involvement of a wide group of stakeholders in valorisation, preservation, management;

Long-term heritage policy (evidence-based and society-based);

New management schemes and innovative business models;

Shift from a preservation-focused to a value-focused approach;

Designing cultural development strategies to boost local and regional competitions and comparative advantage;

Local and regional authorities should actively participate in the management potential of cultural heritage;

Defining quality in relation to interventions on cultural heritage (cultural diversity, inclusion, intangible sense-of-belonging heritage);

Creation of community-based values;

Capacity of cultural heritage to connect social groups.

Identified gaps and opportunities were:

Hard to evaluate social impact;

Promoting volunteering activities;

Use of digital technology—impact on smart specialization strategies;

Cultural heritage’s potential as a strategic resource for Europe;

Cross-sectoral impact;

Heritage—a primarily social resource.

Evaluation of the social impact of investment in cultural heritage is a very complex process and a challenging field to be addressed in further research, especially when considering cultural heritage as a great potential strategic resource for Europe. Accordingly, it would be useful to explore methods for promoting volunteering activities. Cross-sectoral impact could also be further explored as well as digital technologies’ application. Lack of shared standards for the holistic impact assessment of cultural heritage interventions hampers deep holistic understanding of their positive or negative outcomes and the effectiveness of the investments. The recent overarching holistic model for impact assessment of interventions in cultural heritage, such as the one recently proposed by the SoPHIA project (addressed earlier in the text), encompassing four interconnected domains—social, cultural, economic, and environmental—takes on board both cross-cutting issues and the counter effects of any intervention and takes into consideration the time dimension and the people perspective. This provides a new, wider optic for both heritage practitioners and policy-makers in evaluating the value of heritage projects, thus opening a new research venue. Additionally, it calls for even further testing of heritage values to ensure its finetuning and to help recognize a standardized set of indicators, which are able to meet a minimum requirement or quality target, such as sustainability or resilience of the evaluated projects.

Promising innovative methods for assessing investments in cultural heritage, as well as innovative combinations of existing methods, are challenges for further research and understanding of how and why such assessment is crucial for the establishment of cultural heritage interventions.