Co-Movement, Portfolio Diversification, Investors’ Behavior and Psychology: Evidence from Developed and Emerging Countries’ Stock Markets

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Methodology

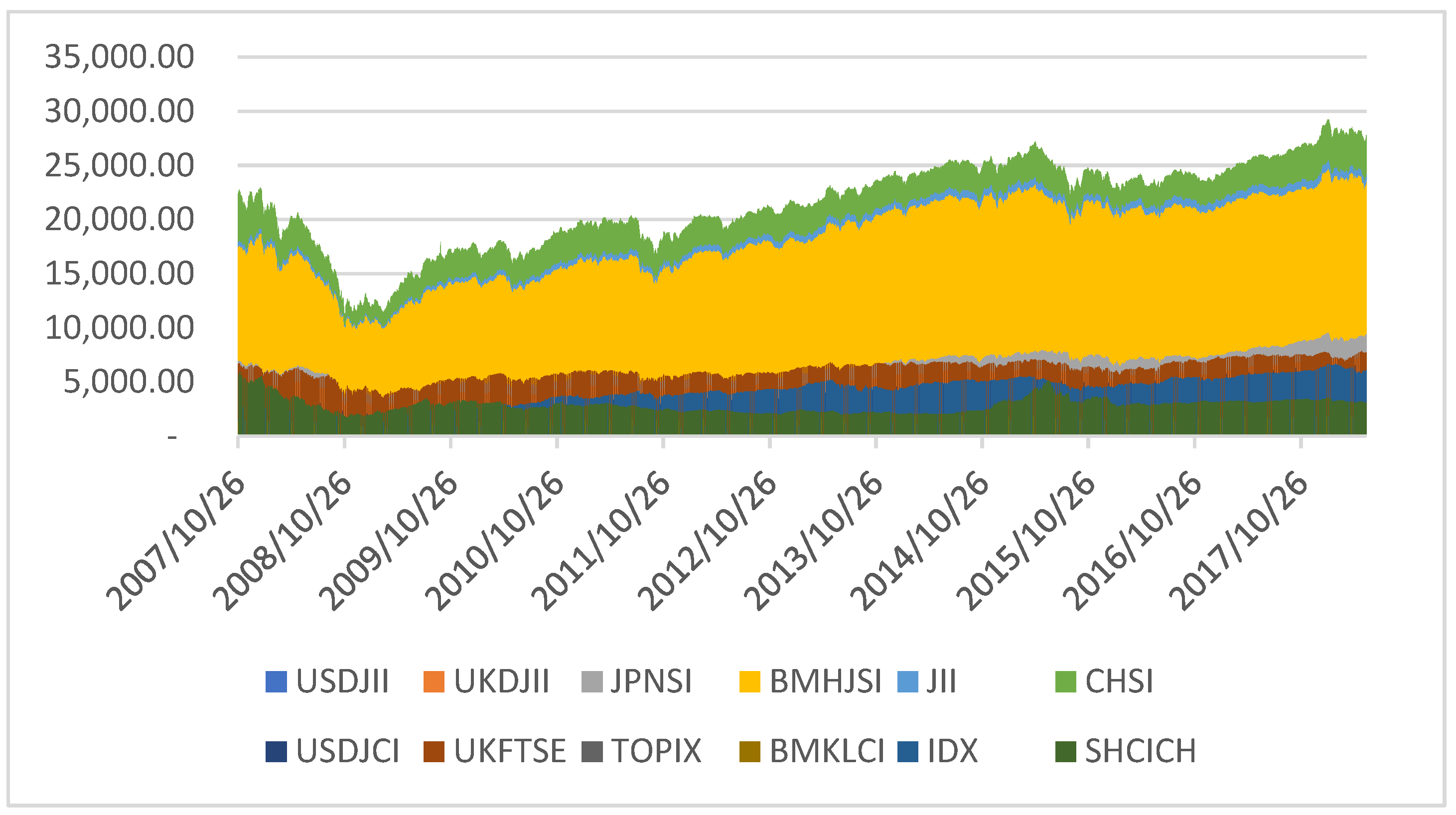

3.1. Data

3.2. Model Specification

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Primary Results

4.2. Summary of Descriptive Statistics

4.3. Wavelet Coherence Transformation (WCT)

4.4. Robustness Check

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aamir, Muhammad, and Syed Zulfiqar Ali Shah. 2018. Determinants of stock market co-movements between Pakistan and Asian emerging economies. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 11: 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abbes, Mouna Boujelbene, and Yousra Trichilli. 2015. Islamic stock markets and potential diversification benefits. Borsa Istanbul Review 15: 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aguiar-Conraria, Luís, and Maria Joana Soares. 2011. The Continuous Wavelet Transform: A Primer (No. 16/2011). Braga: NIPE-Universidade do Minho. [Google Scholar]

- Aguiar-Conraria, Luís, Nuno Azevedo, and Maria Joana Soares. 2008. Using wavelets to decompose the time—Frequency effects of monetary policy. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and Its Applications 387: 2863–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ahmed, Walid M. 2018. How do Islamic versus conventional equity markets react to political risk? Dynamic panel evidence. International Economics 156: 284–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Abdullahi D., and Rui Huo. 2019. Impacts of China’s crash on Asia-Pacific financial integration: Volatility interdependence, information transmission and market co-movement. Economic Modelling 79: 28–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, Md Samsul, Syed Jawad Hussain Shahzad, and Román Ferrer. 2019. Causal flows between oil and forex markets using high-frequency data: Asymmetries from good and bad volatility. Energy Economics 84: 104513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloui, Chaker, Shawkat Hammoudeh, and Hela Ben Hamida. 2015. Co-movement between sharia stocks and sukuk in the GCC markets: A time-frequency analysis. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money 34: 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anas, Muhammad, Ghulam Mujtaba, Sadaf Nayyar, and Saira Ashfaq. 2020. Time-frequency based dynamics of decoupling or integration between Islamic and conventional equity markets. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 13: 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antar, Monia, and Fatma Alahouel. 2019. Co-movements and diversification opportunities among Dow Jones Islamic indexes. International Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management 13: 94–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonakakis, Nikolaos, Tsangyao Chang, Juncal Cunado, and Rangan Gupta. 2018. The relationship between commodity markets and commodity mutual funds: A wavelet-based analysis. Finance Research Letters 24: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baker, Malcolm, Jeffrey Wurgler, and Yu Yuan. 2012. Global, local, and contagious investor sentiment. Journal of Financial Economics 104: 272–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Balli, Faruk, Hatice O. Balli, Rosmy Jean Louis, and Tuan Kiet Vo. 2015. The transmission of market shocks and bilateral linkages: Evidence from emerging economies. International Review of Financial Analysis 42: 349–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuiyan, Rubaiyat Ahsan, Maya Puspa Rahman, Buerhan Saiti, and Gairuzazmi Bin Mat Ghani. 2018. Financial integration between sukuk and bond indices of emerging markets: Insights from wavelet coherence and multivariate-GARCH analysis. Borsa Istanbul Review 18: 218–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuiyan, Rubaiyat Ahsan, Maya Puspa Rahman, Buerhan Saiti, and Gairuzazmi Bin Mat Ghani. 2019. Does the Malaysian sovereign sukuk market offer portfolio diversification opportunities for global fixed-income investors? Evidence from wavelet coherence and multivariate-GARCH analyses. The North American Journal of Economics and Finance 47: 675–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boako, Gideon, and Paul Alagidede. 2017. Co-movement of Africa’s equity markets: Regional and global analysis in the frequency–time domains. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and Its Applications 468: 359–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodart, Vincent, and Bertrand Candelon. 2009. Evidence of interdependence and contagion using a frequency domain framework. Emerging Markets Review 10: 140–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouri, Elie, Rangan Gupta, Seyedmehdi Hosseini, and Chi Keung Marco Lau. 2018. Does global fear predict fear in BRICS stock markets? Evidence from a Bayesian Graphical Structural VAR model. Emerging Markets Review 34: 124–42. [Google Scholar]

- Bouri, Elie, Riza Demirer, Rangan Gupta, and Xiaojin Sun. 2020. The predictability of stock market volatility in emerging economies: Relative roles of local, regional, and global business cycles. Journal of Forecasting 39: 957–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buriev, Abdul Aziz, Ginanjar Dewandaru, Mohd-Pisal Zainal, and Mansur Masih. 2018. Portfolio diversification benefits at different investment horizons during the Arab uprisings: Turkish perspectives based on MGARCH–DCC and wavelet approaches. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade 54: 3272–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, Thomas C., Bang Nam Jeon, and Huimin Li. 2007. Dynamic correlation analysis of financial contagion: Evidence from Asian markets. Journal of International Money and Finance 26: 1206–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chittedi, Krishna Reddy. 2010. Global stock markets development and integration: With special reference to BRIC countries. International Review of Applied Financial Issues and Economics 2: 18–36. [Google Scholar]

- Chuluun, Tuugi. 2017. Global portfolio investment network and stock market co-movement. Global Finance Journal 33: 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahir, Ahmed Mohamed, Fauziah Mahat, Nazrul Hisyam Ab Razak, and A. N. Bany-Ariffin. 2018. Revisiting the dynamic relationship between exchange rates and stock prices in BRICS countries: A wavelet analysis. Borsa Istanbul Review 18: 101–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewandaru, Ginanjar, Syed Aun R. Rizvi, Rumi Masih, Mansur Masih, and Syed Othman Alhabshi. 2014. Stock market co-movements: Islamic versus conventional equity indices with multi-timescales analysis. Economic Systems 38: 553–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Amri, Henda, and Taher Hamza. 2017. Are there causal relationships between Islamic versus conventional equity indices? International Evidence. Studies in Business and Economics 12: 40–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, Román, Vicente J. Bolós, and Rafael Benítez. 2016. Interest rate changes and stock returns: A European multi-country study with wavelets. International Review of Economics & Finance 44: 112. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, Itay. 2012. Empirical literature on financial crises: Fundamentals vs. panic. The Evidence and Impact of Financial Globalization, 523–34. [Google Scholar]

- Gourène, Grakolet Arnold Zamereith, and Pierre Mendy. 2018. Oil prices and African stock markets co-movement: A time and frequency analysis. Journal of African Trade 5: 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubel, Herbert G. 1968. Internationally diversified portfolios: Welfare gains and capital flows. The American Economic Review 58: 1299–314. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, Abul, and Masudul Alam Choudhury. 2019. Islamic Economics: Theory and Practice. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Joyo, Ahmed Shafique, and Lin Lefen. 2019. Stock market integration of Pakistan with its trading partners: A multivariate DCC-GARCH model approach. Sustainability 11: 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kabir, Sarkar Humayun, A. Mansur M. Masih, and Obiyathulla Ismath Bacha. 2017. Risk–profiles of Islamic equities and commodity portfolios in different market conditions. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade 53: 1477–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalfaoui, Rabeh, Mohamed Boutahar, and Heni Boubaker. 2015. Analyzing volatility pillovers and hedging between oil and stock markets: Evidence from wavelet analysis. Energy Economics 49: 540–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Taimur A. 2011. Co-integration of international stock markets: An investigation of diversification opportunities. Economic Review 8: 7. [Google Scholar]

- Lehkonen, Heikki. 2014. Stock market integration and the global financial crisis. Review of Finance 19: 2039–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, Xiyang, Xiaoyue Chen, Bin Li, Tarlok Singh, and Kan Shi. 2021. Predictability of stock market returns: New evidence from developed and developing countries. Global Finance Journal, 100624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, Lixia. 2013. Co-movement of Asia-Pacific with European and US stock market returns: A cross-time-frequency analysis. Research in International Business and Finance 29: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madaleno, Mara, and Carlos Pinho. 2010. Relationship of the multi-scale variability on world indices. Revista De Economia Financiera 20: 69–92. [Google Scholar]

- Majdoub, Jihed, and Walid Mansour. 2014. Islamic equity market integration and volatility spillover between emerging and US stock markets. The North American Journal of Economics and Finance 29: 452–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majdoub, Jihed, Walid Mansour, and Arrak Islem. 2018. Volatility Spillover among Equity Indices and Crude Oil Prices: Evidence from Islamic Markets. Journal of King Abdulaziz University: Islamic Economics 31: 27–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majid, M. Shabri Abd, and M. Shabri. 2018. Who Co-moves the Islamic Stock Market of Indonesia-the US, UK or Japan? Journal of Islamic Economics 10: 267–84. [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz, Harry. 1958. Portfolio Selection. Efficient Diversification of Investments. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mensi, Walid, Shawkat Hammoudeh, and Sang Hoon Kang. 2017a. Risk spillovers and portfolio management between developed and BRICS stock markets. The North American Journal of Economics and Finance 41: 133–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensi, Walid, Syed Jawad Hussain Shahzad, Shawkat Hammoudeh, Rami Zeitun, and Mobeen Ur Rehman. 2017b. Diversification potential of Asian frontier, BRIC emerging and major developed stock markets: A wavelet-based value at risk approach. Emerging Markets Review 32: 130–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensi, Walid, Besma Hkiri, Khamis H. Al-Yahyaee, and Sang Hoon Kang. 2018. Analyzing time–frequency comovements across gold and oil prices with BRICS stock markets: A VaR based on wavelet approach. International Review of Economics& Finance 54: 74–102. [Google Scholar]

- Nagayev, Ruslan, Mustafa Disli, Koen Inghelbrecht, and Adam Ng. 2016. On the dynamic links between commodities and Islamic equity. Energy Economics 58: 125–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najeeb, Syed Faiq, Obiyathulla Bacha, and Mansur Masih. 2015. Does heterogeneity in investment horizo affect portfolio diversification? some insights using M-GARCH-DCC and wavelet correlation analysis. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade 51: 188–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, Sew Lai, Wen Cheong Chin, and Lee Lee Chong. 2017. Multivariate market risk evaluation between Malaysian Islamic stock index and sectoral indices. Borsa Istanbul Review 17: 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Obstfeld, Maurice. 2021. Trilemmas and tradeoffs: Living with financial globalization. In The Asian Monetary Policy Forum: Insights for Central Banking. Singapore: World Scientific, pp. 16–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. 2018. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/iaos2018/programme/IAOS-OECD2018_Elkjaer-Damgaard.pdf (accessed on 19 September 2018).

- Panda, Ajaya Kumar, and Swagatika Nanda. 2017. Short-term and long-term Interconnectedness of stock returns in Western Europe and the global market. Financial Innovation 3: 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rahim, Adam Mohamed, and Mansur Masih. 2016. Portfolio diversification benefits of Islamic investors with their major trading partners: Evidence from Malaysia based on MGARCH-DCC and wavelet approaches. Economic Modelling 54: 425–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reboredo, Juan C., Miguel A. Rivera-Castro, and Andrea Ugolini. 2017. Wavelet-based test of co-movement and causality between oil and renewable energy stock prices. Energy Economics 61: 241252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rua, António, and Luís C. Nunes. 2009. International co-movement of stock market returns: A wavelet analysis. Journal of Empirical Finance 16: 632–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sahabuddin, Mohammad, Junaina Muhammad, Mohamed Hisham Yahya, and Sabarina Mohammed Shah. 2020. Co-movements between Islamic and Conventional Stock Markets: An Empirical Evidence. Jurnal Ekonomi Malaysia 54: 27–40. [Google Scholar]

- Saiti, Buerhan, and Nazrul Hazizi Noordin. 2018. Does Islamic equity investment provide diversification benefits to conventional investors? evidence from the multivariate GARCH analysis. International Journal of Emerging Markets 13: 267–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saiti, Buerhan. 2015. Cointegration of Islamic stock indices: Evidence from five ASEAN countries. International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research 6: 1392–405. [Google Scholar]

- Saiti, Buerhan, Obiyathulla I. Bacha, and Mansur Masih. 2014. The diversification benefits from Islamic investment during the financial turmoil: The case for the US-based equity investors. Borsa Istanbul Review 14: 196–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saiti, Buerhan, Obiyathulla Ismath Bacha, and Mansur Masih. 2016. Testing the conventional and Islamic financial market contagion: Evidence from wavelet analysis. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade 52: 1832–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sakti, Muhammad Rizky Prima, Mansur Masih, Buerhan Saiti, and Mohammad Ali Tareq. 2018. Unveiling the diversification benefits of Islamic equities and commodities: Evidence from multivariate-GARCH and continuous wavelet analysis. Managerial Finance 44: 830–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, Arshian, Chaker Aloui, and Larisa Yarovaya. 2020. COVID-19 pandemic, oil prices, stock market, geopolitical risk and policy uncertainty nexus in the US economy: Fresh evidence from the wavelet-based approach. International Review of Financial Analysis 70: 101496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Anil, and Neha Seth. 2012. Literature review of stock market integration: A global perspective. Qualitative Research in Financial Markets 4: 84–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sifat, Imtiaz, Alireza Zarei, Seyedmehdi Hosseini, and Elie Bouri. 2022. Interbank liquidity risk transmission to large emerging markets in crisis periods. International Review of Financial Analysis 82: 102200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Ge, Zhiqing Xia, Muhammad Farhan Basheer, and Syed Mehmood Ali Shah. 2021. Co-movement dynamics of US and Chinese stock market: Evidence from COVID-19 crisis. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tien, Ho Thuy, and Ngo Thai Hung. 2022. Volatility spillover effects between oil and GCC stock markets: A wavelet-based asymmetric dynamic conditional correlation approach. International Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukovic, Darko B., Kseniya A. Lapshina, and Moinak Maiti. 2021. Wavelet coherence analysis of returns, volatility and interdependence of the US and the EU money markets: Pre & post crisis. The North American Journal of Economics and Finance 58: 101457. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Ling, and Gurjeet Dhesi. 2010. Volatility Spillover and Time-Varying Conditional Correlation between the European and US stock markets. Global Economy and Finance Journal 3: 148–64. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Lu, Xiao Jing Cai, and Shigeyuki Hamori. 2017. Does the crude oil price influence the exchange rates of oil-importing and oil-exporting countries differently? A wavelet coherence analysis. International Review of Economics & Finance 49: 536–47. [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz, Mustafa K., Ahmet Sensoy, Kevser Ozturk, and Erk Hacihasanoglu. 2015. Cross-sectoral interactions in Islamic equity markets. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal 32: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, Qianwei, Tahir Yousaf, Qurat Ul Ain, and Yasmeen Akhtar. 2020. Investor psychology, mood variations, and sustainable cross-sectional returns: A Chinese case study on investing in illiquid stocks on a specific day of the week. Frontiers in Psychology 11: 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Bing, and Xiao-Ming Li. 2014. Has there been any change in the co-movement between the Chinese and US stock markets? International Review of Economics & Finance 29: 525536. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Xi, Yunjia Zhang, Senzhang Wang, Yuntao Yao, Binxing Fang, and S. Yu Philip. 2018. Improving stock market prediction via heterogeneous information fusion. Knowledge-Based Systems 143: 236–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Origin of the Country | Shariah-Compliant Stock Indices | Ticker | Non-Shariah-Compliant Stock Indices | Ticker |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Developed countries | ||||

| USA | Dow Jones Islamic Index | USDJII | Dow Jones Composite Index | USDJCI |

| UK | Dow Jones Islamic Index | UKDJII | FTSE100 Composite Index | UKFTSE |

| Japan | Japan FTSE Shariah index | JPNSI | Tokyo Price Index (TOPIX), Japan | TOPIX |

| Emerging countries | ||||

| Malaysia | FTSE Bursa Malaysia Hijarah Shariah index | BMHJSI | FTSE Bursa Malaysia KLCI Composite Index | BMKLCI |

| Indonesia | Jakarta Islamic Index | JII | Indonesia Composite Index | IDX |

| China | FTSE Shariah Index, China | CHSI | Shanghai Composite Index, China | SHCICHN |

| Islamic Stock Markets | Conventional Stock Markets | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Skew | Kurt | JB | Mean | SD | Skew | Kurt | JB | |

| Developed countries | ||||||||||

| USA | 0.026 | 1.207 | −0.194 | 14.374 | 14,947.93 | 0.022 | 1.179 | −0.238 | 12.021 | 9418.736 |

| UK | −0.005 | 1.495 | −0.167 | 11.297 | 7957.461 | 0.008 | 1.158 | −0.181 | 10.912 | 7240.846 |

| JAPAN | 0.005 | 1.471 | −0.338 | 11.062 | 7554.786 | 0.005 | 1.434 | −0.391 | 10.975 | 7410.729 |

| Emerging countries | ||||||||||

| Malaysia | 0.011 | 0.751 | −1.325 | 25.206 | 57,723.82 | 0.009 | 0.696 | −1.264 | 21.640 | 40,840.45 |

| Indonesia | 0.015 | 1.513 | −0.561 | 10.552 | 6727.99 | 0.030 | 1.281 | −0.668 | 12.401 | 10,407.400 |

| China | −0.008 | 2.192 | −0.302 | 79.935 | 683,196.7 | 0.012 | 1.557 | −0.526 | 11.611 | 8686.063 |

| Scale | UKDJII | JPNSI | BMHJSI | JII | CHSI | USDJCI | UKFTSE | TOPIX | BMKLCI | IDX | SHCICH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| d1 | 0.381 | −0.153 | −0.036 | −0.048 | −0.007 | 0.984 | 0.427 | −0.149 | −0.051 | −0.061 | 0.003 |

| d2 | 0.683 | 0.294 | 0.191 | 0.228 | 0.328 | 0.984 | 0.709 | 0.283 | 0.219 | 0.246 | 0.165 |

| d3 | 0.794 | 0.596 | 0.327 | 0.438 | 0.612 | 0.982 | 0.819 | 0.578 | 0.359 | 0.452 | 0.220 |

| d4 | 0.850 | 0.661 | 0.390 | 0.434 | 0.629 | 0.982 | 0.861 | 0.632 | 0.422 | 0.442 | 0.255 |

| d5 | 0.864 | 0.669 | 0.432 | 0.532 | 0.625 | 0.985 | 0.852 | 0.655 | 0.436 | 0.576 | 0.237 |

| d6 | 0.877 | 0.836 | 0.657 | 0.687 | 0.733 | 0.985 | 0.889 | 0.800 | 0.698 | 0.697 | 0.348 |

| d7 | 0.803 | 0.652 | 0.563 | 0.449 | 0.581 | 0.983 | 0.848 | 0.602 | 0.554 | 0.433 | 0.405 |

| d8 | 0.701 | 0.576 | 0.842 | 0.086 | 0.602 | 0.993 | 0.845 | 0.553 | 0.819 | 0.157 | 0.477 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sahabuddin, M.; Islam, M.A.; Tabash, M.I.; Anagreh, S.; Akter, R.; Rahman, M.M. Co-Movement, Portfolio Diversification, Investors’ Behavior and Psychology: Evidence from Developed and Emerging Countries’ Stock Markets. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2022, 15, 319. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm15080319

Sahabuddin M, Islam MA, Tabash MI, Anagreh S, Akter R, Rahman MM. Co-Movement, Portfolio Diversification, Investors’ Behavior and Psychology: Evidence from Developed and Emerging Countries’ Stock Markets. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2022; 15(8):319. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm15080319

Chicago/Turabian StyleSahabuddin, Mohammad, Md. Aminul Islam, Mosab I. Tabash, Suhaib Anagreh, Rozina Akter, and Md. Mizanur Rahman. 2022. "Co-Movement, Portfolio Diversification, Investors’ Behavior and Psychology: Evidence from Developed and Emerging Countries’ Stock Markets" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 15, no. 8: 319. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm15080319

APA StyleSahabuddin, M., Islam, M. A., Tabash, M. I., Anagreh, S., Akter, R., & Rahman, M. M. (2022). Co-Movement, Portfolio Diversification, Investors’ Behavior and Psychology: Evidence from Developed and Emerging Countries’ Stock Markets. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 15(8), 319. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm15080319