Abstract

The qualitative information of companies’ financial statements provides useful information that can increase the accuracy of bankruptcy prediction models. In this research, a dataset of 924,903 financial statements from 355,704 German companies classified into solvent, financially distressed, and bankrupt companies using the Amadeus database from Bureau van Dijk was examined. The results provide empirical evidence that a corpus linguistic approach implementing evidential strategy analysis towards financial statements helps to distinguish between companies’ financial situations. They show that companies use different approaches and confidence assessments when evaluating their financial statements based on solvency and vary their use of evidential strategies accordingly. This leads to the proposition of a procedure to quantify and generate features based on the analysis of evidential strategies that can be used to improve corporate bankruptcy prediction. The results presented here stem from an interdisciplinary adaptation of linguistic findings and provide future research with another means of analysis in the area of text mining.

1. Introduction

Recently, the use of AI in the context of financial statement analysis to predict corporate bankruptcy has received increasing attention in research (Roumani et al. 2020; Tanaka et al. 2019). Considering the data that a financial statement provides, a distinction must be made between AI approaches that classically use quantitative balance sheet data for the development of AI (Smith and Alvarez 2021) and those that, in contrast, evaluate the text in financial statements to analyze corporate financial situations (Myšková and Hájek 2020). A crucial issue in forecasting corporate insolvency with the help of AI is therefore the combination of information from both components of a financial statement. The data basis of the quantitative financial parameters about the bankruptcy prediction of companies has already been researched extensively (Altman 1968; Altman et al. 1977). A simple keyword search revealed around 9591 articles published on Elsevier Scopus (Elsevier 2022) before 2020 connected to the issue of corporate bankruptcy prediction. The analysis of qualitative text data offers a new optimization approach for existing models that appears quite promising (Chou et al. 2018; Loughran and McDonald 2016; Luo and Zhou 2020). The fact that German companies are required by §289 of the German Commercial Code (HGB 2021) to present their current and prospective situation about opportunities, risks, research, and development further confirms the interest in research in this area. While various established text mining approaches, e.g., sentiment analysis and dictionary-based approaches, in English-language financial statements have already been investigated (Caserio et al. 2020; Loughran and McDonald 2011; Myšková and Hájek 2020), an analysis of corpus linguistic factors concerning argument structures is missing. For the use of text data, it is essential to develop appropriate transparent and reproducible text mining approaches as well (Loughran and McDonald 2016). Nevertheless, in the context of the analysis of German-language annual financial statement data, there are initial text-subdividing approaches that show how extracted information from the risk report of a financial statement can be combined with financial ratios to predict corporate bankruptcies (Lohmann and Ohliger 2020).

In this paper, building on the idea of studying word collocations (Kloptchenko et al. 2004a), the concept of evidential strategies in financial statements is considered. In linguistic research, evidential strategies have received more attention relatively recently. Results showed that specific evidential expressions are linked to specific discourse domains (Marín Arrese 2017) and different instance strategies were observable within scientific discourse and proven to be quantifiable (Hidalgo-Downing 2017). The motivated use of these strategies is linked to a speaker’s commitment to an evaluation (Besnard 2017). An argument should be made that these features could make the use of evidential strategies an important measurement in the examination of corporate financial performance. Thus, the goal here is to investigate the suitability of evidential strategies as such a measurement, as well as to develop an approach to quantify them concerning their use in the development of AI for bankruptcy prediction. Concluding from this, the following research question is formulated:

RQ: How can evidential strategies in financial statements be used for corporate bankruptcy prediction?

In developing an approach based on the examination of evidential strategies, one necessarily needs to draw from the past literature on the use of textual data in financial statements for corporate bankruptcy prediction as well as from the literature on the linguistic category of evidentiality to form an understanding of the corpus-analytical approach that originates in linguistics. Following that, the dataset of German financial statements on which the paper is based shall be presented. The language of the dataset was chosen in the wake of promising results in the analysis of evidentiality in the German language. Proceeding to the qualitative analysis and results, three classes of companies are considered: those that are solvent, those that are financially distressed, and those that are in insolvency proceedings. The paper concludes with providing an outlook for and discussion of implications of the results for theory and practice. Furthermore, limitations of the study as well as future research opportunities are addressed.

2. Theoretical Foundations

In the following, the literature stream on the use of textual information in corporate insolvency prediction using computational methods is summarized. This specific consideration was chosen to properly place the approach within related research, since reviews already exist that deal with bankruptcy prediction of companies in general (Kirkos 2015; Veganzones and Severin 2021). Furthermore, a basis for understanding the linguistic construct of evidential strategies is provided.

2.1. Reviewing the Use of Textual Data in Corporate Bankruptcy Prediction

To situate the approach presented in this study within existing research, already existing research approaches on the use of textual data in corporate bankruptcy prediction shall be reviewed. The review is limited to the literature concerning the usefulness of qualitative information from corporate financial statements and excludes a look at external sources of information. First of all, the goal of using textual data can be defined as the improvement of AI-based model capabilities to predict corporate bankruptcies, the prediction probability of which should be increased as a result (Hájek et al. 2014). Since it is often assumed in the literature that better information can be abstracted rather from the analysis of the text of a financial statement than from the analysis of the statements themselves (Kirkos 2015; Luo and Zhou 2020; Nießner et al. 2021), studies exist that deal with text mining approaches (Shirata et al. 2011) or study combinations of quantitative and qualitative information from financial statements in order to predict companies’ future financial situations (Balasubramanian et al. 2019; Chou et al. 2018). These studies examine the extent to which text features are suitable for predicting bankruptcies, but also the financial situation of a company in general (Kloptchenko et al. 2004b). Therefore, approaches can be identified that examine, e.g., readability (Bushee et al. 2018; Luo and Zhou 2020), the use of hedging terms (Humpherys 2009), and also the sentiment of financial statement textual data (Caserio et al. 2020; Mayew et al. 2015). Moreover, there are text mining approaches that are created exclusively for qualitative data within financial statements as well as studies that analyze companies’ environment variables, e.g., size of a company and industry affiliation, for predicting corporate bankruptcy (Jones 2017; Pamuk et al. 2021; Pasternak-Malicka et al. 2021). Within the scope of a study of German-language annual financial statements, it was shown that the analysis of the risk report in terms of linguistic complexity, length, and emotional presentation provides suitable information for optimizing the bankruptcy prognosis of companies (Lohmann and Ohliger 2020). This is also shown by earlier results that used collocational networks on English-language financial statements to consider partial analyses of texts in the context of forecasting future corporate financial situations (Magnusson et al. 2005). Thus, it is of scientific interest to investigate text mining approaches in the field of corporate insolvency prediction based on annual financial statements in a language-independent manner using data from other countries. Consequently, this motivates the development of a procedure for quantifying the results of the discourse-analytical approach within this research paper to be able to use them accordingly in a bankruptcy prediction model. Incidentally, another finding in looking at research in this area is that there is a trend towards studies that do not make a binary classification into solvent and insolvent companies, but instead propose ratios that allow predicting companies’ financial states more specifically in a larger variety of classes (Balasubramanian et al. 2019; Lohmann and Ohliger 2020; Smith and Alvarez 2021). Reflectively classified in a taxonomy of text mining features (Fromm et al. 2019), it appears that recent approaches differ in terms of their granularity from initial results generated at the document level in the use of textual data for bankruptcy prediction. Consequently, the approach presented in this study takes an exploratory approach through sentence-level analysis.

2.2. Reviewing Evidential Strategies

Evidential strategies are a part of evidentiality, which itself is a cross-linguistic category that was first discussed by Boas (1938), holistically systematized by Aikhenvald (2004), and is described as a general information source marking that also categorizes the manner through which information is acquired. In doing so, it has been shown to display a progressive hierarchy in languages, where so-called evidentials, i.e., grammaticalized semantic categories, are mandatory. In this hierarchy, self-performed actions by a speaker are ranked the highest, followed by visual perception, auditory perception, inferentials, and ending with reported information at the lowest rank of the information source spectrum (Oswalt 1986). Languages that have this coding of information source as an obligatory grammaticalized semantic category are called E1-languages. German, however, does not have evidentiality as a distinct grammatical category. Instead, it belongs to the category of so-called E₂-languages, where evidentiality is encoded through an open set of linguistic devices that develop evidential extensions with explicit or implicit reference to the source of information as a side effect (Fetzer 2014). These so-called evidential strategies serve two functions in E2-languages: providing information about, on the one hand, the existence of a source and, on the other, the mode of how the information was acquired, without, however, being “a function of truth or falsity” (Hardman 1986), and a primary designation encoding the speaker’s confidence towards that evidence.

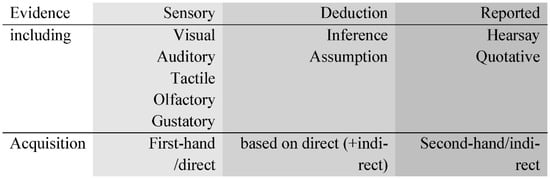

In this paper, the evidential strategies in the data are classified using a modified version of the model introduced by Chafe (1986) that is quasi-analogous to the systematization of evidentials in E1-languages in the respect that it proposes a progressive hierarchy based on knowledge reliability. Whilst Chafe differentiates four modes of knowing, viz. belief, induction, hearsay, and deduction, the proposed model in this paper for German as an E2-language excludes the category of belief, arguing that belief is so deeply rooted within epistemic modality and detached from fact that it cannot possibly constitute an evidential category. Additionally, it was deemed necessary to opt for a supercategory that entails both hearsay and quotation viz. “reported”, since grammatical distinctions between quotative and hearsay evidence are often not present in the aforementioned E2-languages and distinctions between ambiguous hearsay and direct as well as indirect quotations are bound to the same evidential strategies here. The same applies also to inference and assumption: On the one hand, there is a clear distinction between both categories in the sense that inference relies on first-hand acquired evidence that directly motivates a deduction, whereas assumptions do not have a direct connection between what is being witnessed and what it being implied, thus relying on second-hand evidence. On the other hand, both are often used with the same evidential strategy and are thus often only differentiable through qualitative analysis. However, since contextual constraints may hinder these determinations in many cases, it was decided to follow Chafe’s suggestion to subsume both inference and assumption in the supercategory “deduction” for German as an E2-language. In accordance with that the supercategory, “sensory” will be used to describe any form of evidence directly acquired by a speaker, since E2-languages do not draw a binary distinction between a visual and a sensory category. This creates the following model denoting the trinomial segmentation of evidentiality in E2-languages to which German belongs (Figure 1):

Figure 1.

Comprehensive evidence acquisition model.

3. Research Methodology and Dataset

To tackle the research question, this study will employ a discourse-pragmatic frame of reference using an integrated framework that combines quantitative and qualitative methodologies of linguistic corpus analysis within critical discourse analysis (Wodak 2013), as has been a firmly established practice in many linguistic studies of recent years (Nartey and Mwinlaaru 2019). In this case, this means that the corpora will be scanned for German that-clause constructions (dass-Konstruktionen), i.e., subordinate clauses led in by ”that” (dass), which serve as the starting point of our explorative approach. Using quantitative measures, the most frequent verbs carrying evidential extension that introduce these constructions will be determined using the part-of-speech tagset by Schmid and Laws (2008) and collocational analysis, scanning for verb collocates before the node that (dass). Using a discourse-pragmatic frame of reference grounded in linguistics, these verb collocates are then qualitatively analyzed for evidential extension, using the linguistic model that was introduced in Section 2.2. Following that process, these verb + that-clause constructions that carry evidential meaning will then be sorted by frequency to determine the most genre-defining evidential strategies used in financial statements. Using these most frequent evidential constructions as a quantifiable foundation, the collocations behind the verb + that-clause construction node are scanned for adjectives carrying positive/negative semantic meaning in accordance with the systematization by Partington (2015) through quantitative measures and the emerging patterned co-occurrences are analyzed qualitatively for evaluative meanings that may emerge in the textual environment, drawing from Partington (2004) and Sinclair (2004) in accordance with our explorative approach, as this methodology enables us to filter out quantifiable cues in the use and distribution of evidential strategies for the prediction of corporate bankruptcy that could then be systematized in a bankruptcy prediction model.

The underlying dataset of this study consists of 924,903 financial statements randomly selected from the German publication portal Bundesanzeiger that were published between the years 2017 and 2021. The period under consideration was chosen to allow an analysis of data as recent and complete as possible considering the time periods of the publication obligation. The data were initially available in the form of XML files, which made it possible to extract the text itself as well as basic company information, e.g., company name and address data. In total, the dataset is comprised of 355,704 different German companies, whereby no sector-specific restriction of the companies considered was made. The dataset of financial statements was supplemented by a classification of the companies based on the Amadeus database of Bureau van Dijk (Bureau van Dijk 2021). For this purpose, a merge of the data was performed based on the comparison of company names given in the financial statement and the address data of the company using a dedicated Python script. Within the Amadeus database, company-specific information is available, which in the following allows the subdivision of the financial statements into the classification scheme of solvent, financially distressed, and bankrupt companies. The classification shows the latest financial status for the considered and analyzed companies that are published in Amadeus. The distribution of the classes of financial statements identified by the merge resulted in the consideration of 912,640 financial statements of solvent companies, compared to 8953 of financially distressed companies, and 2410 of bankrupt companies. Therefore, the dataset consists of individual financial statements with a minimum text length of 600 characters, a maximum of 1,218,497 characters, and an average of 11,277 characters per entry. Therefore, textual attachments in terms of their wording are considered as well. As a result, three distinctly classified datasets of financial statements are analyzed below according to the financial situation of the publishing companies.

4. Data Analysis and Results

Using the methodology laid out above, the datasets were analyzed using the text analysis software SketchEngine, with which they were initially scanned for verbs carrying evidential extension that introduce German that-clause constructions (dass-Konstruktionen). Across all datasets, the verbs carrying evidential extension that occurred most frequently in those positions were ausgehen von (to assume) and erwarten (to expect), both primarily expressing epistemic predictions with a second meaning of either assumptive evidentiality, in the case of ausgehen von, or, in the case of erwarten, assumptive and/or inferential evidentiality, depending on the acquisition of information. This led to both verbs being positioned in the middle spectrum of the progressive hierarchy of the model introduced in Section 2.2, though erwarten leans towards a higher hierarchy, whilst ausgehen von leans towards a lower one. Scanning for adjectives carrying positive evaluative meaning following the ausgehen von/erwarten + dass (assume/expect + that) node showed that the most frequent evaluative adjectives are the desirable gut (good) and positiv (positive), and the undesirable negativ (negative). While this holds true for all three datasets of this study, their frequencies and contextual use varies distinctively. While the linguistic analysis took place in German, the following examples were also translated into English for illustrative purposes in a way that reproduces the syntactic constructions found in the German samples faithfully. However, there may still be differences in the semantic meaning of words between the two languages that were not picked up by the translation.

4.1. Corpus of Solvent Companies

Looking at the data collected from solvent companies, ausgehen von occurs with a normalized frequency of 75.86 and erwarten with 34.22 per million tokens, respectively. If not marked differently, all following distributional statistics will refer to the specified normalized frequency. Scanning for adjectives carrying evaluative meaning that occur behind the node specified above, the solvent companies’ corpus has positiv co-occurring with a slightly higher frequency with erwarten (1.70) than with ausgehen von (1.26), whereas gut appears distinctly more frequently with ausgehen von (0.94) than with erwarten (0.25). However, it needs to be noted that this discrepancy in frequency can largely be attributed to the fixed phrase illustrated in (1) that appears abundantly in this dataset. The same holds true for another positively evaluated adjective, zufriedenstellend (satisfactorily), which occurs exclusively in this dataset with a normalized frequency of 0.22. In all but eight instances, it is part of the fixed expression seen in (2), which, together with it being limited to the solvent dataset, led to its exclusion from further analysis.

- Hierbei wird davon ausgegangen, dass die Marktteilnehmer in ihrem besten wirtschaftlichen Interesse handeln. (Herein, it will be assumed that all market participants act in their best economic self-interest.)

- Insgesamt erwarten wir, dass sich unsere Geschäfte zufriedenstellend entwickeln werden. (Overall, we expect that our business dealings will develop satisfactorily.)

Much less frequent is the occurrence of negativ that co-occurs with ausgehen von with the rather low normalized frequency of 0.25 and with an even lower 0.15 with erwarten. When co-occurring, negativ mostly does so with negation particles such as kein (no) in (3), ohne (without) in (4) or nicht (not), of which the latter is used by the speaker to either raise a negated deduction (von ausgehen, dass nicht) as in (5) or negate the deduction itself (nicht erwartet, dass) as in (6). Especially noteworthy is the frequent use of intensifiers such as nennenswert (noteworthy), signifikant (significant), and wesentlich (crucial) that, due to being negated, serve a diminutive function here and weaken the use of the negative further. Even if no negation particle is used to express a double negative, whatever negative aspect is brought up in the that-clause construction is still considerably weakened: in (7) the speaker assumes that negative and positive effects will single each other out, stating the company’s globale Aufstellung (global positioning) in the causal adverbial phrase introduced by durch (due to) as a basis for this deduction, whereas the speaker in (8) expects to offset negative effects by means of innovativen Produkte (innovative products) that are made explicit via an instrumental adverbial clause introduced by mit (with). The speaker in (9) assumes a reduction in negative EBIT and bases their deduction on information uttered in the previous utterance through the anaphoric reference daher (hence). This high number of explicit evidence mostly introduced through various adverbial phases makes the evidential deductions transparent for the audience and raises the credibility of the speaker’s deductions by providing explicit evidence.

- 3.

- Wir gehen daher davon aus, dass das Schadensereignis keine negativen Auswirkungen auf die weitere Geschäftstätigkeit von Obermeyer Planen + Beraten haben wird. (We thus assume that the damaging event will have no negative impact on the further contractual capability of Obermeyer Planen + Beraten.)

- 4.

- Das Unternehmen geht jedoch davon aus, dass die Rechtsstreitigkeiten ohne nennenswerte negative Auswirkungen auf die Finanz- oder Ertragslage des Unternehmens beigelegt werden können. (The company assumes, however, that the legal disputes will be able to be put aside without any noteworthy negative impact on the financial or profit performance of the company.)

- 5.

- Wir gehen dabei davon aus, dass sich nicht erneut signifikante negative Sondereinflüsse, auch nicht aus den bestehenden Pensionsverpflichtungen, ergeben werden. (Herein, we assume that new significant negative special influences will not ensue, not even from the existing pension obligations.)

- 6.

- Am 31. Dezember 2015 wird nicht erwartet, dass diese Angelegenheit wesentliche negative Auswirkungen auf die Betriebsergebnisse, Liquidität oder finanzielle Situation haben wird. (As of 31 December 2015, it is not expected that this matter will have a crucial negative effect on results of operations, liquidity or financial condition.)

- 7.

- Durch unsere globale Aufstellung gehen wir davon aus, dass sich positive und negative Effekte weitestgehend ausgleichen und damit beherrschbar sind. (Due to our global positioning we assume that the positive and negative effects will largely offset each other and thus remain manageable.)

- 8.

- Wir erwarten, dass wir diese negativen Einflüsse mit neuen innovativen Produkten bzw. Zustellungssystemen ausgleichen können. (We expect that we can offset these negative influences with new innovative products or delivery systems.)

- 9.

- Insbesondere werden die Investitionen die Basis für die Einrichtung der C-SMC-Produktion durch MCHC legen. Daher gehen wir davon aus, dass wir 2017 das negative EBIT deutlich reduzieren können. (In particular, the investment will lay the foundation for the establishment of C-SMC production by MCHC. Therefore we assume that we can reduce the negative EBIT drastically in 2017.)

As the contextual analysis of the occurrences of negativ in the dataset shows, negatively evaluated assumptions are hardly to be found. On the contrary: evidential statements by the speakers are predominantly positively evaluated. Looking at the occurrences of positiv and gut, this is reinforced by the large number of verbs semantically encoding continuity and progression, especially fortsetzen (continue) in (10), (11), and (16), but also ausbauen (expand) in (13) and übertreffen (surpass) in (15). All these verbs occur in a verb phrase with modal auxiliaries belonging to two semantic domains: the modal auxiliary kann (can/be able to) highlights the (expected) dynamic ability of progress in (10), (11), (13), and (15), whereas werden (will) expresses a strong epistemic prediction and highlights either the speakers’ belief in the evidential assessment of the expected progress of the company as in (12), (14), (16), or in the ability of progress as in (11), (13) and (15).

- 10.

- Es ist zu erwarten, dass das Unternehmen die positive Entwicklung der vergangenen Jahre durch die hoch qualifizierten Mitarbeiter, die sehr gute Ausstattung des Maschinen- und Anlagenparks sowie dem breiten Know-how des Unternehmens weiter fortsetzen kann. (It is to be expected that the company is able to continue the positive progress of the past years due to the highly-qualified employees, the very good equipment of the machine and facility park, as well as the broad know-how of the company.)

- 11.

- Wir erwarten, dass die insgesamt positive Entwicklung der vergangenen Jahre auch in den kommenden Jahren fortgesetzt werden kann. (We expect that the overall positive development of the past years will be able to be continued in the coming years.)

- 12.

- Wir erwarten, dass sich diese Maßnahme 2016 positiv auf das Kapitalanlageergebnis auswirken wird. (We expect that this measure will have a positive effect on the capital investment outcome in 2016.)

- 13.

- Insbesondere ist zu erwarten, dass die gute Marktposition des Unternehmens in Lateinamerika und Afrika weiter ausgebaut werden kann. (Especially, it is to be expected, that the good market position of the company in Latin America and Africa can be expanded further.)

- 14.

- Wir erwarten, dass sich der gute Ausbildungsstand und die hohe Leistungsbereitschaft unserer Mitarbeiter auch künftig positiv auf das Verhältnis unserer Mitglieder und Kunden zu ihrer Bank auswirken werden. (We expect that the high level of training and commitment of our employees will also have a positive impact on the relationship between our members and customers and their bank in the future.)

- 15.

- Zusammenfassend ist daher davon auszugehen, dass die gute Auftragsentwicklung des Berichtsjahres im Jahr 2016 noch einmal übertroffen werden kann. (Summarizing this, it is thus assumed that the good ETO of the 2016 report will be able to be surpassed once again.)

- 16.

- Es ist davon auszugehen, dass sich dieser positive Trend auch in 2016 fortsetzen wird. (It is assumed that this positive trend will also continue in 2016.)

4.2. Corpus of Bankrupt Companies

Scanning for verbs with encoded evidential meaning introducing that-clause constructions of bankrupt companies produces the highest frequency with the same two verbs previously introduced. Although ausgehen von occurs with a slightly raised normalized frequency of 77.93 here, erwarten occurs almost twice as often as in the solvent dataset, displaying a normalized frequency of 76.27 that is on par with ausgehen von. Looking at adjectives carrying evaluative meaning co-occurring with the erwarten/ausgehen von + dass constructions produces very different results as well: ausgehen von has the adjectival collocates positiv and negativ with normalized frequencies of 0.63 and 1.25, but displays a very low frequency of 0.21 for gut, whereas erwarten has gut co-occurring with a comparatively high frequency of 1.04. However, looking at the actual data, it is revealed that these co-occurrences all stem from the exact same sentence, illustrated in (22), that occurs in various financial statements of the same company throughout the years, tainting the significance of the heightened frequency here. The exact same issue can be observed for the co-occurrence of positiv with erwarten + dass in this dataset, where the repeating sentence is (23). The frequency of negativ following the erwarten + dass constructions displays no such issues and is 0.83 per million words. Whereas the vast majority of negativ’s patterned co-occurrences turned out to be double negatives in the solvent dataset, the bankrupt dataset is different: though a small number is still comprised of negative deductions weakened by negated intensifiers (17) or negating the deductions itself (18) and thus rendering the deduced outcome desirable, (20) and (21) are explicitly negatively evaluated and others carry temporality markers such as derzeit (currently), implying the speaker’s prediction may change if contradictory evidence occurs in the future. Other markers that weaken the deduction can be found in (19) and (20): in (19) the premodification of ausgeglichen (offset) with the approximator annähernd (approximately) implies uncertainty of the speaker’s prediction as does the modal adverbial clause in (20): although the speaker expresses a high degree of certainty (hohe Wahrscheinlichkeit) that their deduction is true, it is still a comparatively weaker claim than the deduction illustrated in (21) that is devoid of it. What stands out in all these patterned co-occurrences is the absence of explicit evidence realized by adverbial phrases that was prominently featured co-occurring with the use of evidential strategies in the dataset of solvent companies.

- 17.

- Die Geschäftsführung schätzt die Risiken als überschaubar ein und geht derzeit davon aus, dass sie keinen nennenswerten negativen Einfluss auf die Entwicklung der Gesellschaft haben werden. (The management evaluates the risk as manageable and currently assumes that they will have no noteworthy negative impact on the development of the company.)

- 18.

- Es ist nicht zu erwarten, dass dieser negative Sondereffekt sich in den Folgejahren wiederholen wird. (It is not to be expected that this negative special effect will repeat in the years to follow.)

- 19.

- Die Gesellschaft geht davon aus, dass diese negativen Einflüsse auf Umsatz und Ergebnis im 2. Halbjahr annähernd ausgeglichen werden können. (The company assumes that the negative influences on sales and earnings can be approximately offset again.)

- 20.

- Mit hoher Wahrscheinlichkeit ist zu erwarten, dass die negativen Folgen für die Bank umso stärker sind, je länger die Pandemie anhält. (It is to be expected with a high degree of certainty that the negative implications for the bank will be the greater the longer the pandemic lasts.)

- 21.

- Es ist zu erwarten, dass die negativen Folgen für die Wirtschaftsleistung unserer Bank umso stärker sind, je länger die Pandemie anhält. (It is to be expected that the negative implications for the economic performance of our bank will be the greater the longer the pandemic lasts.)

Furthermore, whereas the solvent dataset showed an abundance of verbs denoting progress occurring within the that-clause constructions with positiv and gut, in this dataset positive growth or progress of the companies, if occurring at all, is dependent on external factors that are made explicit via causal adverbial phrases often led in by aufgrund (due to) and serve as evidential justifications for the speakers’ deductions. The Umsatzwachstum (turnover growth) in (22), for example, can only occur due to a good industry position (Branchenlage) and further expansion (zusätzliche Expansion), and the continuation of the company in (24) is inferred to be predominantly likely (überwiegend wahrscheinlich) only due to the positive continuation prognosis (positive Fortführungsprognose). While there are also some patterned co-occurrences, in which deductions with a positive outlook are devoid of external factors, and reference to evidence for that matter as in (22), most refer to some form of external factors on which a positive, or in the case of (25), a negative, development of the company depends, rendering this an inherent feature of the dataset.

- 22.

- Die Geschäftsleitung erwartet, dass sie aufgrund der guten Branchenlage im E-Commerce Umfeld sowie durch zusätzliche Expansion in andere Produktsegmente, im Jahr 2019 ein Umsatzwachstum von 8-10% im Vergleich zum Vorjahr erreichen kann. (The management expects that in 2019 it can achieve a turnover growth of 8–10% in comparison to the previous year due to the good industry position in the e-commerce environment and further expansion in other product segments.)

- 23.

- Wir erwarten, dass sich diese positive Tendenz auch in den folgenden Jahren als stabilisierender Faktor und signifikanter Wettbewerbsvorteil für das Unternehmen erweist. (We expect that this positive tendency will prove to be a stabilizing factor and significant competitive advantage for the company in the years to come.)

- 24.

- Bilanzierung und Bewertung erfolgten trotz bilanzieller Überschuldung der Gesellschaft zu Fortführungswerten, weil die Geschäftsführung davon ausgeht, dass aufgrund der vorliegenden positiven Fortführungsprognose und der damit von der finanzierenden Bank genehmigten neuen Finanzierungsstruktur die Fortführung der Unternehmenstätigkeit überwiegend wahrscheinlich ist. (Despite the company’s sheet over-indebtedness, balancing and appraisal were done at going concern values because the management assumes that the continuation of the company’s operation is predominantly likely due to the positive going concern forecast and the concomitant approval of the new financing structure by the financing bank.)

- 25.

- Nach allen Informationen die uns vorliegen, müssen wir auch für das Jahr 2017 davon ausgehen, dass unsere Branche von den positiven Rahmenbedingungen speziell in Deutschland nicht profitieren konnte und erhebliche Einbrüche im Umsatz mit Gardinen und Dekostoffen (speziell im Mittelpreissegment) zu verzeichnen waren. (Based on all the information available to us, we must also assume for 2017 that our industry could not benefit from the positive underlying conditions, especially in Germany, and that there were significant downturns in sales of curtains and decorative fabrics (especially in the mid-price segment).)

4.3. Corpus of Financially Distressed Companies

The financially distressed dataset bridges the gap between bankrupt companies and solvent ones. As has been shown to be a universal in the other two datasets, the verbs with an evidential extension introducing a that-clause construction are once again ausgehen von, with a normalized frequency of 47.31 and erwarten, with 48.52. On the one hand, this continues the trend of both verbs occurring with a roughly equal frequency, but on the other hand it is almost exclusively lower than the frequency that was displayed in the other datasets. What is unique to this dataset, however, is that although the total dataset size is twice as large as the bankrupt one, all adjectives carrying evaluative meaning that occur as collocates to ausgehen von + dass constructions occur with the same, albeit low, frequency of 0.19. Erwarten, however, displays evaluative adjectives following a that-clause construction with distinctly higher frequencies, with positiv displaying a normalized frequency of 0.65, negativ displaying 0.74, and gut being entirely absent. Looking at the data in context reveals a similar marking of certainty that was also observable in the bankrupt dataset. In (26), this goes as far as having parts of the deductions of an undesirable development seen in (20) and (21) reoccurring verbatim. What stands out as well is the more complex, hypotactic syntax that emerges when negativ follows an evidential that-clause construction: here, the speakers either state multiple forms of evidence on which their deductions are based, as in (28), or justify the omission of evidence, even making explicit that they are doing so out of self-interest, as in (27), where the speaker appeals to their audience that it would be only logical (vernünftigerweise) to not inform the general public due to the negative repercussions (negative Folgen) this may have on the company.

- 26.

- Mit hoher Wahrscheinlichkeit lässt sich jedoch bereits jetzt erwarten, dass die negative Folgen für die Bank umso stärker sind, je länger die Pandemie anhält. (However, it is already to be expected with a high degree of certainty that the negative impact will be the greater the longer the pandemic lasts.)

- 27.

- Wir beschreiben diese Sachverhalte in unserem Bestätigungsvermerk, es sei denn, Gesetze oder andere Rechtsvorschriften schließen die öffentliche Angabe des Sachverhalts aus oder wir bestimmen in äußerst seltenen Fällen, dass ein Sachverhalt nicht in unserem Bestätigungsvermerk mitgeteilt werden sollte, weil vernünftigerweise erwartet wird, dass die negativen Folgen einer solchen Mitteilung deren Vorteile für das öffentliche Interesse übersteigen würden. (We describe these matters in our auditor’s report unless law or regulation precludes public disclosure of the matter or, in extremely rare circumstances, we determine that a matter should not be communicated in our auditor’s report because the negative repercussions of such communication would logically be expected to outweigh its public interest benefits.)

- 28.

- Die Geschäftsleitung der flatex Bank AG beobachtet die politischen Entwicklungen kritisch, erwartet jedoch, dass eventuell negative Auswirkungen durch den weiteren Ausbau der Aktivitäten mit den bestehenden Partnern sowie neuen Geschäftspartnern im Mandantengeschäft als auch durch neue Handelsprodukte abgemildert werden können. (The management of flatex Bank AG is keeping a critical eye on political developments, but expects that any negative effects can be mitigated by further expanding activities with existing partners and new business partners in the client business, as well as through new trading products.)

This increased need for justification occurring within negatively evaluated evidential strategies is in contrast to the contexts, in which the collocate positiv occurs in this dataset: on the one hand, the assessments of the speakers are overwhelmingly positive, as in (29), where a product (Produkt) is praised by the speaker to have exceeded expectations and on the basis of this, the deduction that the product will continue to do so, is made. On the other hand, the deductions with a desirable outcome that are missing an information source are comparable to the ones observed in the solvent dataset, as in (30).

- 29.

- Das Produkt Logistics übertrifft in den ersten acht Monaten die budgetierten Erwartungen und wir erwarten, dass dieser positive Trend bis Ende 2017 anhält. (The Logistics product exceeded budgeted expectations in the first eight months and we expect that this positive trend continues until the end of 2017.)

- 30.

- Es wird erwartet, dass sich die positive gesamtwirtschaftliche Entwicklung insgesamt fortsetzt. (It is expected that the positive macroeconomic development will continue overall.)

5. Discussion and Implications

This study examines the usefulness of evidential strategies to predict corporate financial distress and bankruptcy based on qualitative data from German companies’ financial statements. It shows that evidential strategies can be used to distinguish between the classes of companies based on the analysis of their textual financial statement data. In terms of frequency, it was determined that ausgehen von and erwarten were the most dominant verbs used in evidential that-clause constructions in German financial statements and thus served as the tertium comparationis.

The strikingly similar distribution of the two verbs under investigation in the financially distressed and bankruptcy datasets suggests that evidential strategies are infrequently used by financially distressed companies and possibly deliberately so. One possible reason for this could be that their financial statements are aimed at diverting from problematic financial situations and especially their causes. That may also be why the linguistic analysis of the few evidential strategies found within this class shows that deductions with positively evaluated adjectives are entirely devoid of evidence, whereas the ones with negatively evaluated adjectives not only display little evidence as well, but are also comprised of complex hypotactic sentence structures and, accordingly, have the longest word count of the identified sentences in these negatively evaluated that-clause constructions. This differs drastically from the other two classes, where the evidence for the various deductions is frequently made explicit through various forms of adverbial phrases and the only difference is the displayed level of certainty of the speakers’ assessments, which is higher with the solvent class due to a number of strong modals displaying the semantic notions of ability and prediction, and lower with the bankrupt class due to a number of uncertainty markers and formulated preconditions introduced through causal adverbials.

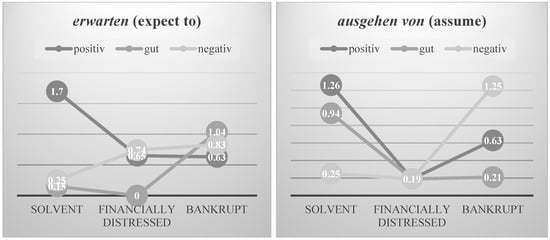

Finally, looking at the mere change in frequency of the positively (gut, positiv) and negatively (negativ) evaluated adjectives illustrated in Figure 2 shows two things: first, apart from negativ following after erwarten, all evaluative adjectives show a pronounced infrequency of use in the financially distressed class that was also visible with evidential strategies, corroborating the suggestion made above. Second, the use of positiv sees a considerable drop in frequency in the bankruptcy class in comparison to the solvent one that seems to be reciprocal to the behavior of negativ, which occurs frequently in the bankrupt class, but displays a much lower frequency in the solvent one. Considering the fact that a closer look showed that, in the case of solvent companies, negatively evaluated adjectives usually occurred negated, rendering the reports of solvent companies by and large desirable even if negatively evaluated adjectives such as negativ occur, this distributional shift may serve as the most important cue for a bankruptcy prediction model based on financial statements. In Section 5.2, a possible preprocessing according to the results shall be presented leading to the ability of feature-generation for a future improvement of AI-based corporate bankruptcy prediction.

Figure 2.

Distribution of evaluative adjectives following evidential strategies in financial statements.

5.1. Contributions to Literature

The analysis of the presented data using a linguistic approach undertaken for this study complements the field of corporate bankruptcy prediction with another option for evaluating textual data from financial statements. The explorative study was able to show that the concept of evidentiality in financial statements contributes to the distinction between solvent, financially distressed, and bankrupt companies. In terms of current approaches, it thus provides a method that can be used to improve future AI-based predictive models for corporate bankruptcy. Based on the idea of the use of collocational networks (Magnusson et al. 2005) and the partial consideration of single components of a text in financial statements (Lohmann and Ohliger 2020; Wei et al. 2019), a new approach for text mining is developed. The data features that can be derived from that allow, on the one hand, the identification of argumentation structures within a financial statement and, on the other hand, the evaluation of the confidence with which they were made. By successfully adapting the concept of evidential strategies for financial statement analysis and presenting a procedure to quantify these findings, an approach for future researchers to explore how the results from this corpus linguistic analysis can be used within various other studies has been introduced.

5.2. Feature Engineering Process and Practical Implications

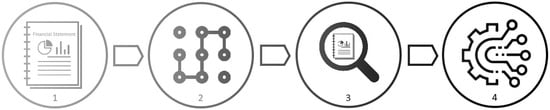

In addition to the theoretical contribution, this study also provides practical implications: the presented approach resulting from this research allows a quantification of the usage of evidential strategies and preprocessed text from financial statements for use in corporate bankruptcy prediction. The approach can be divided into four phases, which are illustrated in Figure 3 below.

Figure 3.

Discourse-analytical text mining process for feature engineering.

In the first phase, the pure textual components of a financial statement must be extracted and separated from the other components, depending on the file format. In the second phase, a pattern is defined, which makes the lemmas of verbs used as evidential strategies that follow a that-clause construction, such as ”to assume” and ”to expect”, recognizable. In the third phase, based on these predefined patterns, the corresponding argumentation structures within the text are identified. Finally, these identified structures are evaluated in the fourth phase as follows: on the one hand, the relative frequency of the use of such constructions is calculated, and on the other hand, adjectives that follow a that-clause construction will be evaluated using a sentiment analysis approach. In this regard, programming with Python enables one way for the recognition and differentiation of adjectives in sentences through the use of part-of-speech tagging (spaCy v3.2 2021) as well as sentiment-based evaluation, e.g., with SentiWS v2.0 (Remus et al. 2010). However, it should be noted that, so far, no sentiment dictionary based on German financial statements tailored to this use case exists. Consequently, this procedure allows the extraction of features for the model development of corporate bankruptcy predictions, which in return enables the extraction and use of not only the frequency but also the structure of statements made within these financial statements.

Furthermore, the possibility of improving predictive models for corporate bankruptcies also enables risk minimization regarding debt accumulation and enables stakeholders to classify the financial situations of companies better. Ultimately, as has been illustrated, the approach demonstrated in this research paper also allows for a non-binary classification of companies’ financial situations.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research Opportunities

As with any research, this study has some limitations that need to be considered when interpreting the results and providing future research opportunities. First, a dataset that is comparatively large was used to analyze the argumentation structures, but still the results cannot be transferred arbitrarily to financial statements in other languages, and, even for the German language, are due to be further investigated. Because this is an early stage of implementing corpus linguistic approaches for bankruptcy prediction models, assessing the influence of evidential strategies on bankruptcy prediction based on future financial statements is not a straightforward task, especially since only financial statements that were published within the limited period of 2017 to 2021 were examined. Thus, further validation of the results should be considered for future research, e.g., in AI-based bankruptcy prediction models. Second, the dataset and, particularly, its status assessment into solvent, financially distressed, and bankrupt companies, is, as other studies in the field have shown (Roumani et al. 2020), subject to class imbalance. Considering the use of factors based on evidential strategies in the development of models to predict corporate bankruptcy, this imbalance issue and the question of how to balance the classes represents another opportunity for future research. Finally, the status labeling of the financial statements is subject to the assumption that the classification using the Amadeus database from Bureau van Dijk, which obtains its information from Creditreform, is appropriate. For future research on financial statements of different countries and different languages, it would therefore be conceivable to apply the results to financial-factors-based classification of the companies to investigate the suitability of evidential strategies in other environments.

6. Conclusions

This study was motivated by the surge of interest in the analysis of qualitative textual data from financial statements for the prediction of corporate bankruptcy. Although initial approaches were conducted in the area of text analysis to optimize bankruptcy prediction, a research gap in the study of presented decisions in financial statements was identified and explored with a linguistic methodology regarding the use of evidential strategies. In this study, insights were taken from linguistic theory and a study on the use of textual data within corporate bankruptcy prediction based on financial statements to answer the predefined research question. Considering the use of statistical models to present a solution to this question that would improve corporate bankruptcy predictions, a new procedure to generate features based on these findings that can enhance the prediction accuracy was developed. It was thus shown that feature engineering based on the concept of evidential strategies is suitable to distinguish between the classes of solvent, financially distressed, and bankrupt companies. Finally, it has to be noted that this study presents results based on German financial statements, but also suggests an adaption to incorporate textual data into the development of statistical models for the analysis of financial statements from other countries. The next step would be to further explore to what extent quantitative financial statement analysis can be complemented with insights from qualitative analysis through the use of AI to predict corporate bankruptcies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.N. and D.H.G.; methodology, T.N. and D.H.G.; formal analysis, D.H.G. and T.N.; data curation, T.N. and M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, T.N. and D.H.G.; writing—review and editing, T.N., D.H.G., and M.S.; visualization, T.N. and D.H.G.; validation, T.N. and D.H.G.; project administration, M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

We acknowledge support by the Open Access Publication Funds of the Göttingen University.

Data Availability Statement

Partial publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. These data can be found here: https://www.bvdinfo.com/en-us/our-products/data/international/amadeus (accessed on 25 July 2022). The financial statement data are not publicly available due to data protection reasons of an external partner.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the reviewers for their thoughtful comments and efforts towards improving our manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Aikhenvald, Alexandra Y. 2004. Evidentiality. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Altman, Edward I. 1968. Financial ratios, discriminant analysis and the prediction of corporate bankruptcy. The Journal of Finance 4: 589–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, Edward I., Robert G. Haldemann, and Paul Narayanan. 1977. ZETA™ analysis: A new model to identify bankruptcy risk of corporations. Journal of Banking and Finance 1: 29–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, Senthil A., G. S. Radhakrishna, Periaiya Sridevi, and Thamaraiselvan Natarajan. 2019. Modeling corporate financial distress using financial and non-financial variables. International Journal of Law and Management 3: 457–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besnard, Anne-Laure. 2017. BE likely to and BE expected to, epistemic modality or evidentiality? In Evidentiality Revisited. Edited by Juana I. Marín Arrese, Gerda Haßler and Marta Carretero. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 249–69. [Google Scholar]

- Boas, Franz. 1938. Language in General Anthropology. Edited by F. Boas. Boston: D.C. Heath and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Bureau van Dijk. 2021. Amadeus Database. Available online: https://www.bvdinfo.com/de-de/unsere-losungen/daten/international/amadeus (accessed on 3 November 2021).

- Bushee, Brian J., Ian A. Gow, and Daniel J. Taylor. 2018. Linguistic Complexity in Firm Disclosures: Obfuscation or Information? Journal of Accounting Research 1: 85–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caserio, Carlo, Delio Panaro, and Sara Trucco. 2020. Management discussion and analysis: A tone analysis on US financial listed companies. Management Decision 3: 510–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chafe, Wallace L. 1986. Evidentiality: The Linguistic Coding of Epistemology. Norwood: Ablex Publishing Corp. [Google Scholar]

- Chou, Chi-Chun, Janie C. Chang, Chen-Lung Chin, and Wei-Ta Chiang. 2018. Measuring the Consistency of Quantitative and Qualitative Information in Financial Reports: A Design Science Approach. Journal of Emerging Technologies in Accounting 2: 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsevier. 2022. Scopus. Available online: https://www.scopus.com (accessed on 28 September 2022).

- Fetzer, Anita. 2014. Foregrounding evidentiality in (English) academic discourse: Patterned co-occurrences of the sensory perception verbs seem and appear. Intercultural Pragmatics 3: 333–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fromm, Hansjörg, Thiemo Wambsganss, and Matthias Söllner. 2019. Towards a Taxonomy of Text Mining Features. Paper presented at the ECIS Proceedings 2019, Stockholm, Sweden, June 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Hájek, Petr, Vladimir Olej, and Renáta Myšková. 2014. Forecasting corporate financial performance using sentiment in annual reports for stakeholder’s decision-making. Technological and Economic Development of Economy 4: 721–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardman, Martha J. 1986. Data-source Marking in the Jaqi Languages. In Evidentiality: The Linguistic Coding of Epistemology. New York: Ablex, p. 136. [Google Scholar]

- HGB. 2021. Handelsgesetzbuch §289—Inhalt des Lageberichts. Available online: https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/hgb/__289.html (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Hidalgo-Downing, Laura. 2017. Evidential and Epistemic Stance Strategies in Scientific Communication in Evidentiality Revisited. Edited by Juana I. Marín Arrese, Gerda Haßler and Marta Carretero. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 225–48. [Google Scholar]

- Humpherys, Sean L. 2009. Discriminating Fradulent Financial Statements by Identifying Linguistic Hedging. Paper presented at the AMCIS Proceedings 2009, San Francisco, CA, USA, August 6–9. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Stewart. 2017. Corporate bankruptcy prediction: A high dimensional analysis. Review of Accounting Studies 3: 1366–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkos, Efstathios. 2015. Assessing methodologies for intelligent bankruptcy prediction. Artificial Intelligence Review 1: 83–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloptchenko, Antonia, Camilla Magnusson, Barbro Back, Ari Visa, and Hannu Vanharanta. 2004a. Mining Textual Contents of Financial Reports. The International Journal of Digital Accounting Research 7: 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloptchenko, Antonina, Tomas Eklund, Jonas Karlsson, Barbro Back, Hannu Vanharanta, and Ari Visa. 2004b. Combining data and text mining techniques for analysing financial reports. Intelligent Systems in Accounting, Finance & Management 1: 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohmann, Christian, and Thorsten Ohliger. 2020. Bankruptcy prediction and the discriminatory power of annual reports: Empirical evidence from financially distressed German companies. Journal of Business Economics 1: 137–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughran, Tim, and Bill McDonald. 2011. When Is a Liability Not a Liability? Textual Analysis, Dictionaries, and 10-Ks. The Journal of Finance 1: 35–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughran, Tim, and Bill McDonald. 2016. Textual Analysis in Accounting and Finance: A Survey. Journal of Accounting Research 4: 1187–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Yan, and Linying Zhou. 2020. Textual tone in corporate financial disclosures: A survey of the literature. International Journal of Disclosure and Governance 17: 101–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnusson, Camilla, Antti Arppe, Tomas Eklund, Barbro Back, Hannu Vanharanta, and Ari Visa. 2005. The language of quarterly reports as an indicator of change in the company’s financial status. Information & Management 4: 561–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín Arrese, Juana I. 2017. Multifunctionality of Evidential Expressions in Discourse Domains and Genres in Evidentiality Revisited. Edited by Juana I. Marín Arrese, Gerda Haßler and Marta Carretero. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 195–223. [Google Scholar]

- Mayew, William J., Mani Sethuraman, and Mohan Venkatachalam. 2015. MD&A disclosure and the firm’s ability to continue as a going concern. The Accounting Review 90: 1622–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myšková, Renáta, and Petr Hájek. 2020. Mining risk-related sentiment in corporate annual reports and its effect on financial performance. Technological and Economic Development of Economy 6: 1422–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nartey, Mark, and Isaac N. Mwinlaaru. 2019. Towards a decade of synergising corpus linguistics and critical discourse analysis: A meta-analysis. Corpora 2: 203–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nießner, Tobias, Robert C. Nickerson, and Matthias Schumann. 2021. Towards a taxonomy of AI-based methods in Financial Statement Analysis. Paper presented at the AMCIS Proceedings 2021, Montreal, QC, Canada, August 9–13. [Google Scholar]

- Oswalt, Robert. L. 1986. The Evidential System of Kashaya. In Evidentiality: The Linguistic Coding of Epistemology. Edited by Wallace L. Chafe and Johanna Nichols. Norwood: Ablex Publishing Corp, pp. 20–29. [Google Scholar]

- Pamuk, Mustafa, René O. Grendel, and Matthias Schumann. 2021. Towards ML-based Platforms in Finance Industry—An ML Approach to Generate Corporate Bankruptcy Probabilities based on Annual Financial Statements. Paper presented at the ACIS Proceedings 2021, Sydney, Australia, December 6–10. [Google Scholar]

- Partington, Alan. 2004. Utterly content in each other’s company. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 1: 131–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partington, Alan. 2015. Evaluative prosody. In Corpus Pragmatics. Edited by Karin Aijmer and Christoph Rühlemann. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 279–303. [Google Scholar]

- Pasternak-Malicka, Monika, Anna Ostrowska-Dankiewicz, and Robert Dankiewicz. 2021. Bankruptcy—An assessment of the phenomenon in the small and medium-sized enterprise sector-case of poland. Polish Journal of Management Studies 1: 250–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remus, Robert, Uwe Quasthoff, and Gerhard Heyer. 2010. SentiWS—A Publicly Available German-language Resource for Sentiment Analysis. Paper presented at the LREC Proceedings 2010, Valletta, Malta, May 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Roumani, Yazan F., Joseph K. Nwankpa, and Mohan Tanniru. 2020. Predicting firm failure in the software industry. Artificial Intelligence Review 6: 4161–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, Helmut, and Florian Laws. 2008. Estimation of conditional probabilities with decision trees and an application to fine-grained POS tagging. Paper presented at the Coling 2008 Proceedings, Manchester, UK, August 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Shirata, Cindy Y., Hironori Takeuchi, Shiho Ogino, and Hideo Watanabe. 2011. Extracting Key Phrases as Predictors of Corporate Bankruptcy: Empirical Analysis of Annual Reports by Text Mining. Journal of Emerging Technologies in Accounting 8: 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, John, ed. 2004. Trust the Text: Language, Corpus and Discourse. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Matthew, and Francisco Alvarez. 2021. Predicting Firm-Level Bankruptcy in the Spanish Economy Using Extreme Gradient Boosting. Computational Economics 59: 263–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- spaCy v3.2. 2021. spaCy: Industrial-Strength NLP. Available online: https://github.com/explosion/spaCy (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Tanaka, Katsuyuki, Takuo Higashide, Takuji Kinkyo, and Shigeyuki Hamori. 2019. Analyzing industry-level vulnerability by predicting financial bankruptcy. Economic Inquiry 4: 2017–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veganzones, David, and Eric Severin. 2021. Corporate failure prediction models in the twenty-first century: A review. European Business Review 2: 204–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Lu, Guowen Li, Xiaoqian Zhu, and Jianping Li. 2019. Discovering bank risk factors from financial statements based on a new semi-supervised text mining algorithm. Accounting & Finance 3: 1519–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wodak, Ruth. 2013. Critical Discourse Analysis. Los Angeles: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).