The Road from Money to Happiness

Abstract

:1. Introduction

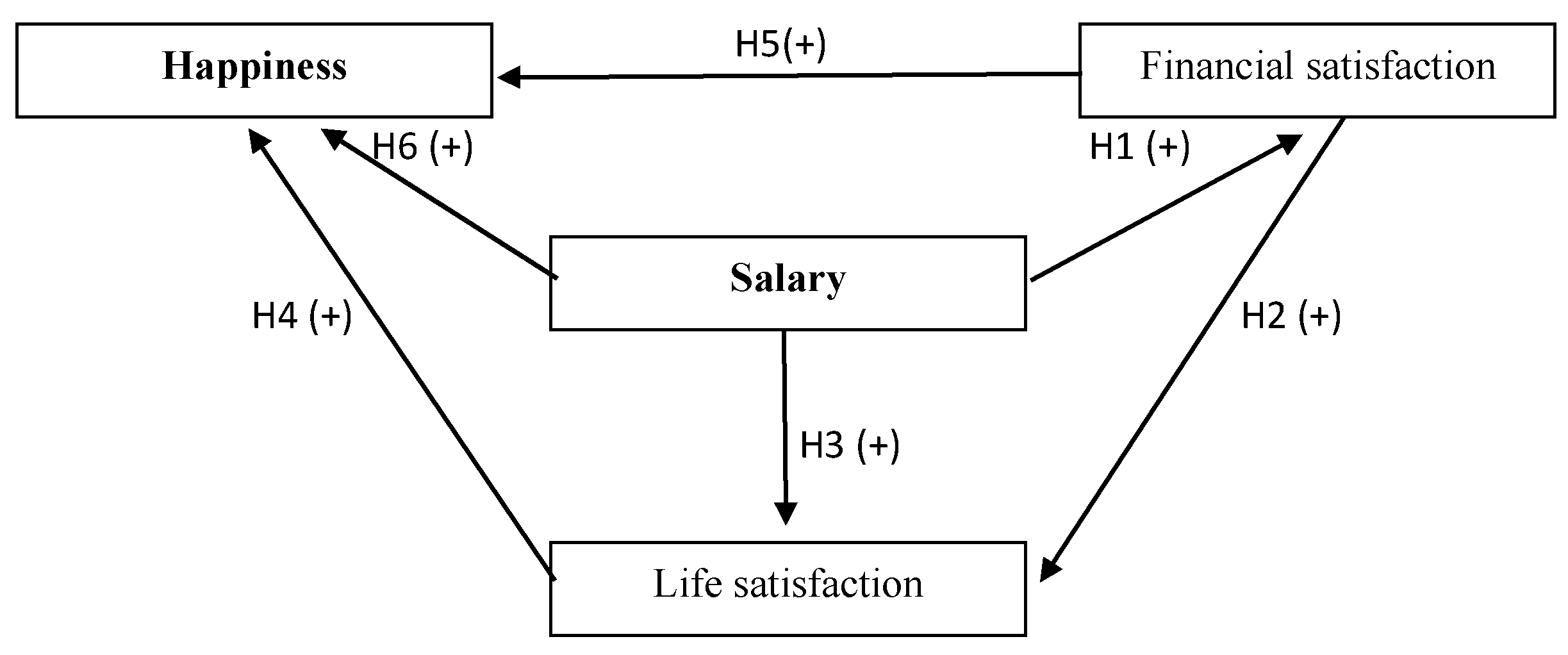

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

3. Research Methodology, Tool and Data

3.1. The Financial Satisfaction Scale (FSS)

3.1.1. The Satisfaction with Life Scale (SLS)

3.1.2. The Subjective Happiness Scale (SHS)

4. Results

5. Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical and Managerial Implication

5.2. Limitation and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Construct | Scale | Label | Item * | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Life Satisfaction | The Subjective Happiness Scale | L1 | In most ways my life is close to my ideal. | Lyubomirsky and Lepper (1999) |

| L2 | The conditions of my life are excellent. | |||

| L3 | I am satisfied with my life. | |||

| L4 | So far I have gotten the important things I want in life. | |||

| L5 | If I could live my life over, I would change almost nothing. | |||

| Happiness | The Satisfaction with Life Scale | H1 | In general, I consider myself: | Diener et al. (1985) |

| H2 | Compared with most of my peers, I consider myself: | |||

| H3 | Some people are generally very happy. They enjoy life regardless of what is going on, getting the most out of everything. To what extent does this characterization describe you? | |||

| H4 | Some people are generally not very happy. Although they are not depressed, they never seem as happy as they might be. To what extent does this characterization describe you. | |||

| Financial Satisfaction | The Financial Satisfaction with Salary | F1 | I am satisfied with my salary. | Morgan (1992); Diener et al. (1985). |

| F2 | Compared with most of my peers, I consider my salary: |

References

- Achim, Monica Violeta, Sorin Nicolae Borlea, Lucian Vasile Găban, and Ionut Constantin Cuceu. 2016. Rethinking the shadow economy in terms of happiness. Evidence for the European Union Member States. Technological and Economic Development of Economy 24: 199–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ali, Azwadi, Mohd Shaari Abd Rahman, and Alif Bakar. 2015. Financial Satisfaction and the Influence of Financial Literacy in Malaysia. Social Indicators Research 120: 137–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, Frank, and Stephen Withey. 1976. Social Indicators of Wellbeing: America’s Perception of Life Quality. New York: Plenum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Argyle, Michael. 1999. Causes and Correlates of Happiness, apud: Daniel Kahneman. In Well-Being: The Foundations of Hedonic Psychology. Edited by Ed Diener and Norbert Schwarz. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, pp. 353–73. [Google Scholar]

- Arifin, Agus Zainul. 2018a. Influence factors toward financial satisfaction with financial behavior as intervening variable on Jakarta area workforce. European Research Studies Journal 21: 90–103. [Google Scholar]

- Arifin, Agus Zainul. 2018b. Influence of financial attitude, financial behavior, financial capability on financial satisfaction. Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research (ASSEHR) 186: 100–3. [Google Scholar]

- Arthaud-Day, Marne, and Janet Near. 2005. The wealth of nations and the happiness of nations: Why ‘‘accounting’’ matters. Social Indicators Research 74: 511–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowling, Ann, and Joy Windsor. 2001. Towards the good life: A population survey of dimensions of quality of life. Journal of Happiness Studies 2: 55–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Sarah, Karl Taylor, and Stephen Wheatley Price. 2005. Debt and Distress: Evaluating the Psychological Cost of Credit. Journal of Economic Psychology 26: 642–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzozowski, Jan, and Nicola Coniglio. 2021. International Migration and the (Un) happiness Push: Evidence from Polish Longitudinal Data. International Migration Review. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Jiaoli, Li Zhang, Yulin Zhao, and Peter Coyte. 2018. Psychological mechanisms linking county-level income inequality to happiness in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15: 2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Campbell, Angus, Philip Converse, and Willard Rodgers. 1976. The Quality of American Life: Perceptions, Evaluations, and Satisfaction. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Conde-Sala, Josep, Cristina Portellano-Ortiz, Laia Calvó-Perxas, and Josep Garre-Olmo. 2017. Quality of life in people aged 65+ in Europe: Associated factors and models of social welfare—Analysis of data from the SHARE project (Wave 5). Quality of Life Research 26: 1059–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cummins, Robert. 2000a. Personal income and subjective well-being: A review. Journal of Happiness Studies 1: 133–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, Robert. 2000b. Objective and Subjective Quality of Life: An Interactive Model. Social Indicators Research 52: 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuong, Nguyen Viet. 2021. Does money bring happiness? Evidence from an income shock for older people. Finance Research Letters 39: 101605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danish, Muhammad Hassan, and Hafeez Ur Rehman Khan. 2021. Mediating role of financial satisfaction between income and subjective wellbeing: An evidence from Pakistan. International Journal of Happiness and Development 6: 220–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, Elizabeth, and Walter Schumm. 1987. Family financial satisfaction: The impact of reference point. Home Economics Research Journal 14: 123–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delhey, Jan. 2004. Life Satisfaction in an Enlarged Europe. European Foundation for the improvement of Living and Working Conditions. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. [Google Scholar]

- DePianto, David. 2011. Financial satisfaction and perceived income through a demographic lens: Do different race/gender pairs reap different returns to income? Social Science Research 40: 773–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, Ed Emmons, Randy Robert Larsen, and Sharon Griffin. 1985. The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment 49: 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, Ed, and Martin Seligman. 2004. Beyond money: Toward an economy of well-being. Psychological Science in the Public Interest 5: 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, Ed, and Robert Biswas-Diener. 2002. Will money increase subjective well-being? Social Indicators Research 57: 119–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, Ed, and Shigehiro Oishi. 2000. Money and happiness: Income and subjective well-being across nations. Culture and Subjective Well-Being, 185–218. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, Ed, Shigehiro Oishi, and Louis Tay. 2018. Advances in subjective well-being research. Nature Human Behaviour 2: 253–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, Ed. 1984. Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin 95: 542–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, Theo K., and Jörg Henseler. 2015. Consistent and asymptotically normal PLS estimators for linear structural equations. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis 81: 10–23. [Google Scholar]

- DiTella, Rafael, and Robert MacCulloch. 2010. Happiness adaptation to income beyond “basic needs”. In International Differences in Well-Being. Edited by Diener Ed, Kahneman Daniel and Helliwell John. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 217–46. [Google Scholar]

- Doh, Young Yim, and Ji-Bum Chung. 2020. What Types of Happiness Do Korean Adults Pursue?—Comparison of Seven Happiness Types. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17: 1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Draughn, Peggy, Ronda LeBoeuf, Patricia Wozniak, Frances Lawrence, and Lisa Welch. 1994. Divorcee’s economic well-being and financial adequacy as related to interfamily grants. Journal of Divorce and Remarriage 22: 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterlin, Richard. 1974. Does economic growth improve the human lot? Some empirical evidence. In Nations and Households in Economic Growth: Essays in Honour of Moses Abramovitz. Edited by David Paul and Melvin Reder. New York: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Easterlin, Richard. 1975. An economic framework for fertility analysis. Studies in Family Planning 6: 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Easterlin, Richard. 1995. Will raising the incomes of all increase the happiness of all? Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 27: 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterlin, Richard. 2006. Life cycle happiness and its sources: Intersections of psychology, economics and demography. Journal of Economic Psychology 27: 463–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fanning, Andrewand, and Daniel O’Neill. 2019. The Wellbeing–Consumption paradox: Happiness, health, income, and carbon emissions in growing versus non-growing economies. Journal of Cleaner Production 212: 810–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer-i-Carbonell, Ada. 2005. Income and well-being: An empirical analysis of the comparison income effect. Journal of Public Economics 89: 997–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederick, Shaneand, and George Loewenstein. 1999. 16 hedonic adaptation. Well-Being. In The Foundations of Hedonic Psychology. Edited by Kahneman Daniel, Diener E. Ed and Norbert Schwarz. New York: Russell Sage, pp. 302–29. [Google Scholar]

- Freedman, Vicki. 2017. The Panel Study of Income Dynamics’ Wellbeing and Daily Life Supplement (PSID-WB) User Guide: Final Release 1. Michigan: Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- Frey, Bruno, and Alois Stutzer. 2002. What can economists learn from happiness research? Journal of Economic Literature 40: 402–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frijters, Paul, John Haisken-De New, and Kerstin Shields. 2004. Money does matter! Evidence from increasing real income and life satisfaction in East Germany following reunification. American Economic Review 94: 730–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fugl-Meyer, Axel R., Inga-Britt Bränholm, and Kerstin S. Fugl-Meyer. 1991. Happiness and domain-specific life satisfaction in adult northern Swedes. Clinical Rehabilitation 5: 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gino, Francesca, and Cassie Mogilner. 2014. Time, money, and morality. Psychological Science 25: 414–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godwin, Deborah. 1994. Antecedents and consequences of newlyweds’ cash flow management. Financial Counseling and Planning 5: 161–90. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, Caroland, and Stefano Pettinato. 2004. Happiness and Hardship: Opportunity and Insecurity in New Market Economies. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press. [Google Scholar]

- Greenley, James, Jan Steven Greenberg, and Roger Brown. 1997. Measuring quality of life: A new and practical survey instrument. Social Work 42: 244–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagerty, Michael, and Ruut Veenhoven. 2003. Wealth and happiness revisited–growing national income does go with greater happiness. Social Indicators Research 64: 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joe F., Christian M. Ringle, and Marko Sarstedt. 2011. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice 19: 139–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halim, Yopie Kurnia Erista, and Dewi Astuti. 2015. Financial stressors, Financial Behaviour, risk tolerance, financial solvency, financial knowledge and financial satisfaction. Journal of Management 3: 19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, Thomas. 2012. Parenthood and happiness: A review of folk theories versus empirical evidence. Social Indicators Research 108: 29–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hartung, Johanna, Sandy Spormann, Morten Moshagen, and Oliver Wilhelm. 2021. Structural Differences in Life Satisfaction in a US Adult Sample across Age. Journal of Personality. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Headey, Bruce, Ruud Muffels, and Mark Wooden. 2008. Money does not buy happiness: Or does it? A reassessment based on the combined effects of wealth, income and consumption. Social Indicators Research 87: 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, Jörg, Christian Ringle, and Marko Sarstedt. 2015. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 43: 115–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Henseler, Jörg, Christian Ringle, and Rudolf Sinkovics. 2009. The use of partial least squares path modeling in international mar-keting. In New Challenges to International Marketing. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited, pp. 277–319. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, Jörg, Geoffrey Hubona, and Pauline Ray. 2016. Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: Updated guidelines. Industrial Management & Data Systems 116: 2–20. [Google Scholar]

- Hilgert, Marianne, Jeanne Hogarth, and Sondra Beverly. 2003. Household financial management: The connection between knowledge and behavior. Federal Reserve Bulletin 89: 309–22. [Google Scholar]

- Hira, Tahiraand, and Olive Mugenda. 1999a. Do men and women differ in their financial beliefs and behaviors? Proceedings of Eastern Family Economics Resource Management Association 1999: 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Hira, Tahiraand, and Olive Mugenda. 1999b. The relationships between self-worth and financial beliefs, behavior, and satisfaction. Journal of Family and Consumer Sciences 91: 76–82. [Google Scholar]

- Hitka, Milos, Peter Štarchoň, Zdenek Caha, Silvia Lorincová, and Mariana Sedliačiková. 2021. The global health pandemic and its impact on the mo-tivation of employees in micro and small enterprises: A case study in the Slovak Republic. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja 2021: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitka, Milos, Zoltan Rózsa, Marek Potkany Potkány, and Lenka Ližbetinová. 2019. Factors forming employee motivation influenced by regional and age-related differences. Journal of Business Economics and Management 20: 674–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hitka, Milso, Silvia Potkány Lorincová, Zaneta Marek Balážová, and Zdenek Caha. 2020. Differentiated approach to employee motivation in terms of finance. Journal of Business Economics and Management 22: 118–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, Geert. 1984. Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values. Southend Oaks: Sage, vol. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, Chang-Ming. 2004. Income and financial satisfaction among older adults in the United States. Social Indicators Research 66: 249–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, Mansi, Gagan Deep Sharma, and Mandeep Mahendru. 2019. Can i sustain my happiness? A review, critique and research agenda for economics of happiness. Sustainability 11: 6375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jebb, Andrew, Louis Tay, Ed Diener, and Shigehiro Oishi. 2018. Happiness, income satiation and turning points around the world. Nature Human Behaviour 2: 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, Sarahand, and Rick Delbridge. 2014. In pursuit of happiness: A sociological examination of employee identifications amongst a ‘happy’call-centre workforce. Organization 21: 867–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeries, Nahell, and Chriss Allen. 1986. Satisfaction/dissatisfaction with financial management among married students. Paper presented at American Council on Consumer Interests Annual Conference, St. Louis, MO, USA, May 18–21; pp. 63–69. [Google Scholar]

- Joo, So-hyun, and John Grable. 2004. An exploratory framework of the determinants of financial satisfaction. Journal of Family and Economic Issues 25: 25–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, Sohyun. 2008. Personal financial wellness. In Handbook of Consumer Finance Research. New York: Springer, pp. 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, Timothy, Ronald Piccolo, Nathan Podsakoff, John Shaw, and Bruce Rich. 2010. The relationship between pay and job satisfaction: A meta-analysis of the literature. Journal of Vocational Behavior 77: 157–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, Daniel, and Angus Deaton. 2010. High income improves evaluation of life but not emotional well-being. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107: 16489–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kaiser, Till, Marie Hennecke, and Maike Luhmann. 2020. The interplay of domain- and life satisfaction in predicting life events. PLoS ONE 15: e0238992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalleberg, Arneand, and Peter Marsden. 2012. Labor force insecurity and U.S. work attitudes, 1970s–2006. In Social trends in American Life. Edited by Marsden Peter. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 315–37. [Google Scholar]

- Killingsworth, Matthew. 2021. Experienced well-being rises with income, even above $75,000 per year. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118: e2016976118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knight, John, Song Lina, and Ramani Gunatilaka. 2009. Subjective well-being and its determinants in rural China. China Economic Review 20: 635–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kühner, Stefan, Maggie Lau, Jin Jiang, and Zhuoyi Wen. 2019. Personal income, local communities and happiness in a rich global city: Evidence from Hong Kong. Journal of Asian Public Policy, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshmanasamy, Thangamuthu, and Kumar Maya. 2020. Is it income adaptation or social comparison? The effect of relative income on happiness and the Easterlin paradox in India. The Indian Economic Journal 68: 477–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, Robert. 2000. The Loss of Happiness in Market Economies. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Layard, Richard. 2011. Happiness: Lessons from a New Science. London: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Jianbo. 2018. Unemployment and Happiness Adaptation: The Role of the Living Standard. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3382599 (accessed on 3 October 2018).

- Lyubomirsky, Sonja, and Heidi Lepper. 1999. A measure of subjective happiness: Preliminary reliability and construct validation. Social Indicators Research 46: 137–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddux, Esther. 2002. A behavioral model to optimize financial quality of life. Social Indicators Research 60: 155–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayraz, Guy, Gert Wagner, and Jürgen Schupp. 2009. Life Satisfaction and Relative Income: Perceptions and Evidence. SOEP paper No. 214, CEP Discussion Paper No. 938. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1476385 (accessed on 3 October 2018). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Michalos, Alex. 2008. Education, Happiness and Wellbeing, Social Indicator Research: An International and Interdi-clipinary. Journal for Quality of Life Measurement 87: 347–66. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, James. 1992. Health, work, economic status, and happiness. Aging, money, and life satisfaction. Aspects of Financial Gerontology 1992: 101–33. [Google Scholar]

- Okulicz-Kozaryn, Adam, and Lonnie Golden. 2018. Happiness is flextime. Applied Research in Quality of Life 13: 355–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okulicz-Kozaryn, Adam, Oscar Holmes, and Derek Avery. 2014. The subjective Well-Being political paradox: Happy welfare states and unhappy liberals. Journal of Applied Psychology 99: 1300–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pavot, William, and Ed Diener. 1993. Review of the satisfaction with life scale. Psychological Assessment 5: 164–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, Nancy, and Thomas Garman. 1993. Testing a conceptual model of financial wellbeing. Financial Counseling and Planning 4: 135–64. [Google Scholar]

- Rohrer, Julia, and Stefan Schmukle. 2018. Individual importance weighting of domain satisfaction ratings does not increase validity. Collabra Psychology 4: 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schyns, Peggy. 2001. Income and satisfaction in Russia. Journal of Happiness Studies 2: 173–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, Feng, Bing Li, Law Yu, Wa Yik, and Paul Yip. 2019. Beyond the Resource Drain Theory: Salary satisfaction as a mediator between commuting time and subjective well-being. Journal of Transport & Health 15: 100631. [Google Scholar]

- Sighieri, Chiara, Gustavo Desantis, and Maria Letizia Tanturri. 2006. The richer, the happier? An empirical investigation in selected European countries. Social Indicators Research 79: 455–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirgy, Joseph, Stephan Grzeskowiak, and Don Rahtz. 2007. Quality of college life (QCL) of students: Developing and validating a measure of well-being. Social Indicators Research 80: 343–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staubli, Silvia, Martin Killias, and Bruno Frey. 2014. Happiness and victimization: An empirical study for Switzerland. European Journal of Criminology 11: 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steel, Piers, Vasyl Taras, Uggerslev Uggerslev, and Frank Bosco. 2018. The happy culture: A theoretical, meta-analytic, and empirical review of the relationship between culture and wealth and subjective well-being. Personality and Social Psychology Review 22: 128–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stevenson, Betse, and Justin Wolfers. 2008. Economic Growth and Subjective Well-Being: Reassessing the Easterlin Paradox (No. w14282). Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson, Betsey, and Justin Wolfers. 2013. Subjective well-being and income: Is there any evidence of satiation? American Economic Review 103: 598–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tatarkiewicz, Wladyslaw. 1976. Analysis of Happiness. Melbourne International Philosophy Series. Hague: Martinus Nijhoff. [Google Scholar]

- Tomini, Florian, Sonila Tomini, and Wim Groot. 2016. Understanding the value of social networks in life satisfaction of elderly people: A comparative study of 16 European countries using SHARE data. BMC Geriatrics 16: 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Praag, Bernard, Paul Frijters, and Ada Carbonell. 2003. The anatomy of well-being. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 51: 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Praag, Bernard. 1968. Individual Welfare Functions and Consumer Behavior: A Theory of Rational Irrationality. Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Van Praag, Bernard. 1971. The Welfare Function of Income in Belgium: An Empirical Investigation. European Economic Review 2: 337–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Praag, Bernard. 2004. The Connexion Between Old and New Approaches to Financial Satisfaction, Cesifo Working Paper No. 1212. Available online: https://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/86635 (accessed on 3 October 2018).

- Veenhoven, Ruut. 1991. Is happiness relative? Social Indicators Research 24: 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera-Toscano, Esperanza, Victoria Ateca-Amestoy, and Rafael Serrano-Del-Rosal. 2006. Building financial satisfaction. Social Indicators Research 77: 211–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Voorhees, Clay, Michael Brady, Roger Calantone, and Edward Ramirez. 2016. Discriminant validity testing in marketing: An analysis, causes for concern, and proposed remedies. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 44: 119–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, Richard, and Kate Pickett. 2009. The Spirit Level: Why More Equal Societies Almost Always Do Better. London: Allen Lane. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, Richard, and Kate Pickett. 2018. The Inner Level: How More Equal Societies Reduce Stress, Restore Sanity and Improve Everyone’s Well-Being. London: Allen Lane. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Jing Jian, Chuanyi Tang, and Soyeon Shim. 2009. Acting for happiness: Financial behavior and life satisfaction of college students. Social Indicators Research 92: 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Jing Jian. 2008. Applying behavior theories to financial behavior. In Handbook of Consumer Finance Research. Edited by Xiao Jing Jian. New York: Springer, pp. 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Dijkstra-Henseler’s Rho (ρA) | Jöreskog’s Rho (ρc) | Cronbach’s Alpha (α) | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Life Satisfaction | 0.8850 | 0.8833 | 0.8826 | 0.6027 |

| Happiness | 0.8810 | 0.7639 | 0.7689 | 0.5068 |

| Financial Satisfaction | 0.8320 | 0.8300 | 0.7905 | 0.7095 |

| Interpretation | More than 0.7, in line with (Hair et al. 2011; Porter and Garman 1993) | Not lower than 0.6, in line with (Morgan 1992) | More than 0.7, in line with (Greenley et al. 1997) | Minimum of 0.5, in line with (Morgan 1992) |

| Indicator | Life Satisfaction | Happiness | Financial Satisfaction |

|---|---|---|---|

| L1 | 0.7032 | ||

| L2 | 0.7965 | ||

| L3 | 0.8125 | ||

| L4 | 0.7962 | ||

| L5 | 0.7687 | ||

| H1 | 0.8690 | ||

| H2 | 0.7751 | ||

| H3 | 0.6924 | ||

| H4 | 0.7903 | ||

| F1 | 0.8423 | ||

| F2 | 0.8423 |

| Construct | Life Satisfaction | Happiness | Net Salary | Financial Satisfaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Life Satisfaction | ||||

| Happiness | 0.7087 | |||

| Net Salary | 0.1502 | 0.1199 | ||

| Financial Satisfaction | 0.6671 | 0.7132 | 0.2614 |

| Effect | Original Coefficient | Standard Bootstrap Results | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Value | Standard Error | t-Value | p-Value (2-Sided) | p-Value (1-Sided) | Evidence | ||

| Life Satisfaction -> Happiness | 0.7951 | 0.8180 | 0.2227 | 3.5700 | 0.0004 | 0.0002 | H4 supported |

| Net Salary -> Life Satisfaction | 0.1800 | 0.1760 | 0.0844 | 2.1335 | 0.0331 | 0.0166 | H3 supported |

| Net Salary -> Happiness | 0.1055 | 0.1043 | 0.0517 | 2.0395 | 0.0417 | 0.0208 | H6 supported |

| Net Salary -> Financial Satisfaction | 0.6009 | 0.1962 | 0.0935 | 2.1479 | 0.0320 | 0.0160 | H1 supported |

| Financial Satisfaction -> Life Satisfaction | 0.8964 | 0.8958 | 0.0218 | 41.1452 | 0.0008 | 0.0004 | H2 supported |

| Financial Satisfaction -> Happiness | 0.5254 | 0.5318 | 0.0687 | 7.6463 | 0.0070 | 0.0036 | H5 supported |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mureșan, G.M.; Fülöp, M.T.; Ciumaș, C. The Road from Money to Happiness. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2021, 14, 459. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14100459

Mureșan GM, Fülöp MT, Ciumaș C. The Road from Money to Happiness. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2021; 14(10):459. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14100459

Chicago/Turabian StyleMureșan, Gabriela Mihaela, Melinda Timea Fülöp, and Cristina Ciumaș. 2021. "The Road from Money to Happiness" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 14, no. 10: 459. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14100459

APA StyleMureșan, G. M., Fülöp, M. T., & Ciumaș, C. (2021). The Road from Money to Happiness. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 14(10), 459. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14100459