Abstract

Immigration is a controversial topic that draws much debate. From a human sustainability perspective, immigration is disadvantageous for home countries causing brain drains. Ample evidence suggests the developed host countries benefit from immigration in terms of diversification, culture, learning, and brain gains, yet less is understood for emerging countries. The purpose of this paper is to examine the presence of brain gains due to immigration for emerging countries, and explore any gaps as compared to developed countries. Using global data from 88 host and 109 home countries over the period from 1995 to 2015, we find significant brain gains due to immigration for emerging countries. However, our results show that there is still a significant brain gain gap between emerging and developed countries. A brain gain to the developed host countries is about 5.5 times greater than that of the emerging countries. The results hold after addressing endogeneity, self-selection, and large sample biases. Furthermore, brain gain is heterogenous by immigrant types. Skilled or creative immigrants tend to benefit the host countries about three times greater than the other immigrants. In addition, the Top 10 destination countries seem to attract the most creative people, thus harvest the most out of the talented immigrants. In contrast, we find countries of origin other than the Top 10 seem to send these creative people to the rest of the world.

1. Introduction

Innovation and technological advancement are building blocks for the long-term sustainable growth and productivity of an economy (Aghion and Howitt 1992; Jones 1995; Romer 1990). Behind all innovations, there are creative human minds. Therefore, the world is competing to attract the brightest minds and the labor market for them has become increasingly mobile. The global immigrant stock was 145.1 million in 1990, yet by the year 2019, it reached 261.8 million, which is 3.4% of the total global population, and 1.8 times more than three decades ago1. Immigration policies in the U.S. through its H1B program, in UK and Canada through their point systems target to attract the selective skilled groups who can meaningfully contribute to the development. Indeed, immigrants make noticeable contributions to science and innovation. For example, the majority of the Nobel laureates in physics and chemistry (Moser et al. 2014), more than 25% to innovations and entrepreneurship (Kerr and Kerr 2020), about 40% of Ph.D. degrees in STEM, and more than 50% in engineering and computer science (Kerr 2019) are attributable to foreign-born immigrants in the U.S.

Despite its benefits, immigration still is a controversial topic that draws much debate. Some would argue that only few origin countries win from the global migration while the majority are losing exacerbating the imbalance (Beine et al. 2008). More recent studies argue that migration is not a zero-sum game, with proper institutions it can be a win-win situation for both home and host countries (Mi et al. 2020; Naghavi and Strozzi 2015; Vissak and Zhang 2014). However, the extant literature largely focused on developed countries in the context of the US (Bernstein et al. 2019; Kerr and Lincoln 2010; Moser et al. 2014), Canada (Beach et al. 2007; Blit et al. 2020), Australia (Clarke et al. 2019), UK (Nathan 2015), and OECD countries (Liu et al. 2010; Ortega and Peri 2009). The literature on developing countries is generally theoretical, with very few empirical analyses focused on a single country only.

The purpose of this paper is twofold. First, empirically examine the presence of brain gains for emerging host countries. According to the World Intellectual Property Organization’s reports, contribution of emerging countries to the world innovation remains low and lagging behind (World Intellectual Property Organization 2019). Therefore, second, we compare the degree of brain gains between emerging and developed countries. With matched data of non-resident patents by 35 emerging and 64 developed countries of origin to 36 emerging and 52 developed host countries over the period from 1995–2015, we study the association between immigration and the non-resident patent rates.

After controlling for host country variables, and year fixed effects, we find evidence of significant brain gains due to immigration. From an increase of immigrants by 1000 per 1 million population, a host country benefits from an increase of non-resident patents by 100 per 1 million population. However, we find significant brain gain gap between emerging and developed countries. Brain gain benefits to the developed countries are approximately 5.5 times greater than that of emerging countries. From an increase of 1000 immigrants per 1 million population, while a developed country benefits by an increase of 110 non-resident patents per 1 million population, an emerging country benefits by an increase of 20 non-resident patents only. An association between the total immigration and the total innovation aggregated at the host country level shows even stronger results economically, statistically, and with much stronger explanatory power.

By further looking into immigrants by their country of origin, we find heterogeneity in brain gains. Immigrants coming from either highly educated or R&D intensive countries tend to benefit the host countries most. Brain gains from immigrants coming from highly educated countries tend to be 2.4 times higher than the immigrants coming from less educated countries. In addition, if the immigrants coming from R&D intense countries, the benefits are three times bigger than less intense countries. Furthermore, developed host countries tend to harvest the benefits of these educated, and inventive immigrants by promoting resources and opportunities. The findings are consistent with the literature on skilled immigrants’ outputs in developed host countries (Akcigit et al. 2017; Burchardi et al. 2020; Hunt and Gauthier-Loiselle 2010). Interestingly, though we do not find significant differences between educated vs. less educated; research-minded vs. non-research-minded immigrants coming to emerging host countries. The results imply that the treatments or policies in the emerging countries are not strong enough to attract skilled immigrants. Our findings for emerging countries support previous arguments that the innovations in emerging countries are driven by needs, rather than opportunities thus less contributive to the innovations (Anokhin and Wincent 2012; Bratti and Conti 2018).

We test the sensitivity of our analyses to Top 10 destination and Top 10 origin countries versus the rest of the world. Although the results consistently hold in these various subsample specifications, we find the brain gains to the Top 10 destination countries are 5.6 times higher than the rest of the world, and almost 4 times higher than the baseline results. For the Top 10 origin countries, we find the opposite result. It is the rest of the world that derives much of the result, and we see much smaller brain gain contribution coming from the Top 10 home countries. We conclude that it might be while Top 10 destination countries are the most popular, thus creative and talented citizens would prefer to live there, deriving much of the results. On the other hand, the Top 10 country of origin might not be the competitive environment for their citizens, that is why they might be losing more of their citizens to the rest of the world. It seems the background and upbringings of the immigrants do play significant roles, and people coming from these regions of the world are contributing less to the innovation than the rest of the world.

We realize that immigration is not a pure exogenous event. Rather, people who immigrate to other countries do so consciously by evaluating their destination countries among others, potential benefits, and threats. At the same time, some host countries implement progressive immigration policies to attract the most talented global pool. We conduct 2SLS regression analyses with push-factor instruments from home countries to address the endogeneity issue. Furthermore, to address self-selection bias, we use propensity score matching to create a more balanced sample and rerun the analyses. In our 2SLS and propensity score analyses, our results continue to hold, and we find significant brain gains for emerging countries, yet there is still brain gain gap as compared to the developed countries.

Our study contributes to the literature with a focus on developing countries There is little evidence about immigrants to the emerging countries, and how they might contribute to the host country’s innovation. We conduct cross country analyses, rather than a single country. Therefore, the results are more generalizable. In addition, it fills the gap in the literature by conducting comparative analyses between developed versus emerging countries. The study has implications on the emerging host country’s immigration, policies for growth, and development with indirect implications on human capital sustainability.

The rest of the paper is organized as below. In Section 2, we provide the literature review, and develop our hypotheses; in Section 3, we explain the methodology; in Section 4, we explain our results and robustness tests; and in Section 5, we provide conclusions, explain the limitations of the research, and suggestions for future research.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

Opponents of immigration make arguments from both the home and host country’s perspectives. From the home country’s perspective, sending their brightest and creative people to the rest of the world can endanger the nation’s human capital sustainability (Beine et al. 2008; Docquier and Rapoport 2012; Grubel 1966). Sustainable Development Goals 2030 formulated by the United Nations emphasize the importance of reducing inequality and improving education quality for a sustainable future for all. From the host country’s perspective, a large flow of immigrants might deplete national resources, crowd out local employees, creating tension between local and immigrant employees, and exacerbate wage inequality (Das et al. 2020). Furthermore, communication barriers could reduce mutual trust, and the exclusions of minority groups could lead to social unrest and conflicts (Alesina and La Ferrara 2005). In absence of synergy with the host institution, productivity and inventive capability could be at risk (Mi et al. 2020).

Despite the above arguments, the positive evidence of immigration on innovation is outnumbered. Hunt and Gauthier-Loiselle (2010) document that in the US, the innovation rate by immigrants outweighs natives. They find that a one percentage point increase in population share leads to a 9–18 percent increase in patents per capita. Similarly, immigrants with Chinese and Indian origins contribute significantly to innovation (Kerr and Lincoln 2010). Immigration not only directly impacts innovation, but also has positive spillover effects on their American peers’ productivity (Bernstein et al. 2019), patent collaborations (Kerr 2008), and innovation diffusions to local neighbors (Burchardi et al. 2020). Brain gains expand beyond the US to include European countries (Bosetti et al. 2012; Ozgen et al. 2012) and growth in OECD countries (Ortega and Peri 2009).

Furthermore, recent studies prove that brain gains due to immigration do not have to be a zero-sum game so that immigrants can bring benefits to their home countries contributing to the development. Immigrants maintain their ties, invest in their home countries, give back by knowledge-sharing, collaborations, and technology diffusions (Kerr 2008; Naghavi and Strozzi 2015). Leveraging on their local knowledge and relationships, they meaningfully contribute to their host firm internationalization with expansion into their home countries with mutual benefits on both sides (Vissak and Zhang 2014). Some entrepreneurs work mobile and return to their country of origin with knowledge spillovers and the best practices (Liu et al. 2010).

Most of the above studies are conducted for developed countries, without much application to the emerging countries. The handful of studies that examine emerging countries are descriptive and limited to policy recommendations (Aldieri et al. 2020). Low-quality amenities and underdeveloped infrastructure in emerging host economies are not comparable to the developed counterparties. Instead, these emerging countries might draw unskilled immigrants mostly for cheap wages in labor-intensive sectors. No significant benefits from immigration on innovations found in Italy may be due to the fact that a large portion of immigrants are unskilled (Bratti and Conti 2018). Innovations in Russia are clustered at few local centers without much diffusion to the other regions of the country (Crescenzi and Jaax 2017). Aldieri et al. (2020) examined migration inflows both outside of the country and domestically within the regions in Russia. While there is no significant impact of domestic migration on innovation, they find a significant positive impact of international immigrants. Kuzior et al. (2020) documented that Ukrainian immigrants in Europe do not utilize their fullest potential due to the cultural shocks and hurdles they face in the host country. Uncertainty and differences in perception results in an imbalance and demotivation.

Host institutions and policy reforms are important to retain brain gains from immigration (Davenport and Bibby 1999; Goldberg et al. 2011; Mayda 2010). Open policies for global talents, and opportunities for growth for MNEs’ shown to be a significant factor for China’s development (Kerr 2008; Liu et al. 2010; Vissak and Zhang 2014). Therefore, building on the above arguments that immigration enriches idea generation, collaborations, and knowledge diffusion, we assume the brain gains are still applicable to the emerging countries, and hypothesize below:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Emerging countries benefit from brain gains from immigration so that the non-resident patent rate increases with the immigrant rate.

Elo (2016) argued that immigrants coming to emerging host countries are significantly different from the ones who are coming to the developed host countries in terms of their entrepreneurial motivations. Immigrant entrepreneurs in the developed countries seek the best opportunities for themselves, thus offer the most valuable ideas and creations to the host country. In contrast, immigrant entrepreneurs in emerging countries start businesses out of survival, so such need-based innovations are not strong enough for rapid growth. In a business-to-business setting, Anokhin and Wincent (2012) derive similar conclusions why start-ups in developed economies make differences due to their opportunity-driven incentives, while at the same time, start-ups in emerging countries are need-driven and cannot contribute to the innovation as much.

Besides their motivations, immigrants can be heterogeneous by their skills. Because major industries that contribute to the economy in emerging countries tend to be labor-intensive, they may attract more unskilled immigrants (Bratti and Conti 2018). On the other hand, developed countries rely on advanced technologies, as such they tend to attract more skilled immigrants. Furthermore, Desmet et al. (2018) highlight potential mobility frictions due to the costs associated with migration, particularly for low-income countries. Indeed, our data show more frequent migration within emerging country groups, with a lower portion of immigrants transferring to developed countries widening the inequality gap.

Alesina and La Ferrara (2005) highlight a significant difference in institutional advancement between emerging and developed countries. Because of the strong institution, developed countries are more inclusive of diversity. The production process is sufficiently complex so that diversity in ethnicity and skills becomes complementary to improve output and performance. On the other hand, skills can be easily substituted for less advanced technologies in emerging economies. If a preference is given to a certain group or a minor ethnicity is excluded in a fragmented society, conflicts could be exacerbated and property rights could be weakened.

Emerging economies lack proper policies, resources, and R&D facilities which hinder them to harvest the most benefits from the talented immigrant pool. Naghavi and Strozzi (2015) emphasized the role of intellectual property right policy for promoting the development and growth in emerging economies. There are still significant gaps in FDI inflows and friction-free policies for MNEs entering into the host economies. Because of heterogeneity in immigrant incentives, skills, background, and host country’s institutional development and innovation-friendly environment between emerging and developed countries, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

There is a brain gain gap between developed and emerging countries.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data

We obtain non-resident patent data from the World Intellectual Property Organization’s database. It reports the number of non-resident patents for a host country narrowed down by each home country origin for each year. Next, we obtain global immigration data from the United Nations’ website. The database covers global immigrant stocks by destination and home countries from 1990 to 2019 for every five years. We merge the two databases based on host, home countries, and the years and come up with a sample of 34,554 observations. We drop 13,000 observations for missing immigration, and 14,933 observations for missing patents and left with a sample of 6621 observations. Further, we obtain country control variables from the World Bank and Heritage Foundation databases and merge them with our sample using host country indicators and years. After dropping missing values for control variables, our final sample consists of 5042 host-home country-year observations.

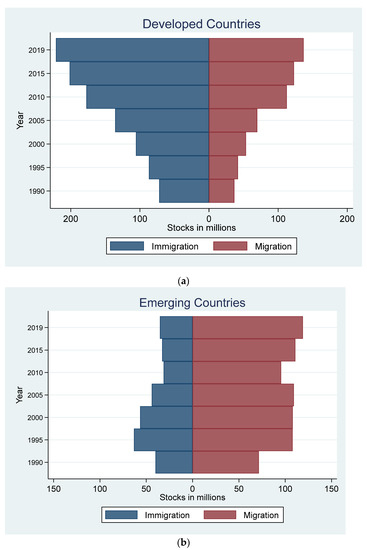

We present immigration data for both developed and emerging countries in Figure 1a,b. Figure 1a shows both immigrant and migrant stocks for developed countries. Over the last three decades, immigrant stocks in developed countries continue to rise from 72.05 million in 1990 to 221.37 million in 2019, while migrant stocks rise from 36.73 million in 1990 to 136.93 million in 2019. As a result, we see net immigrant inflow to the developed countries. In Figure 1b, we show the same immigrant and migrant stocks for emerging countries. While immigrant stocks in the emerging countries are relatively stable over the years, 39.98 million in 1990 and slightly dropped to 35.26 million in 2019, migrant stocks increased from 71.49 million in 1990 to 119.12 million in 2019. As a result, we realize net migrant outflow from emerging countries. Putting it together, we realize more in and outflow volume for developed countries as compared to the emerging country group. However over time, while more people are coming to the developed countries for immigration purposes, we see more people are fleeing out of the emerging countries.

Figure 1.

The immigration and migration of Developed and Emerging countries. (a,b) show both immigrant and migrant stocks for developed countries and emerging countries respectively.

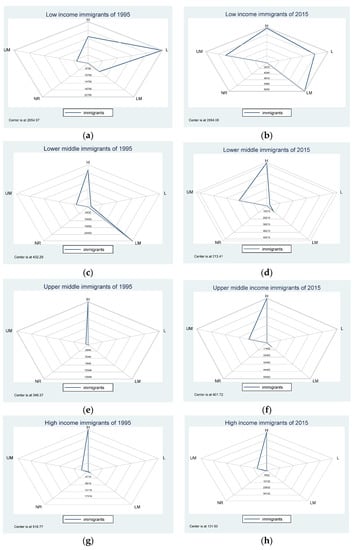

In Figure 2, we visually present immigration among various income groups for the years 1995 and 2015. The majority of the citizens from the low and lower-middle-income countries of origin (shown in Figure 2a,c) tend to immigrate within the same income groups in 1995. However, there is an upward mobility shift to the upper-middle and high-income countries of destinations (shown in Figure 2b,d) by the year 2015. When we examine where the developed countries’ migrants go in Figure 2e–h, they immigrated within the same upper-middle and high-income country groups which stayed the same over time.

Figure 2.

Immigration destination (in thousands). (a,b) show the immigration destination for low-income countries in 1995 and 2015. (c,d) show the immigration destination for lower-middle-income countries in 1995 and 2015. (e,f) show the immigration destination for upper-middle-income countries in 1995 and 2015. (g,h) show the immigration destination for high-income countries in 1995 and 2015.

We identify 88 unique host countries welcoming immigrants from 109 unique home countries over the years 1995, 2000, 2005, 2010, and 2015. Global total immigrant stocks reached 261.7 million by 2019, and in Table 1, we report the Top 10 destination and origin countries. Immigrants to the United States alone is 48.1 million and represents about 18.4 percent of the global immigrant stocks. While Top 10 destinations welcome 50.9 percent of the total immigrants over the years, Top 10 origins lost 34.5 percent of their people to other countries. Based on the World Bank’s classification with 41 host countries, about 46.6 percent of our sample countries are considered as emerging, the remaining 47 host countries, 53.4 percent of the sample are considered as developed2. We present group mean difference t-test results between emerging and developed host countries in Table 2.

Table 1.

This table shows the Top 10 destination and Top 10 origin countries for immigrants. The number of immigrants represents the cumulated immigrant stock of the country for 2019, and the share of each country is computed as a percentage in aggregate global immigration over the same period.

Table 2.

This table reports the summary statistics and the group mean difference t-test results for emerging and developed country groups.

Although the emerging and developed host country groups are not statistically significantly different in terms of the number of immigrants per 1 thousand population, they are significantly different by the number of non-resident patents per 1 million population. The developed countries are better off by 3.6 more patents that are 3.5 times bigger than that of emerging host countries. Emerging countries are lagging in terms of education rate, R&D expense, net export, attracting foreign direct investment inflows, as well as GDP per capita. Additionally, emerging countries are more densely populated with an average population of 146.7 million than the developed countries whose average population is 54.5 million. Furthermore, emerging countries benefit more from the remittances which contribute 3 percent more to the GDP as compared to the developed world. The two groups are not statistically significantly different in terms of their openness index.

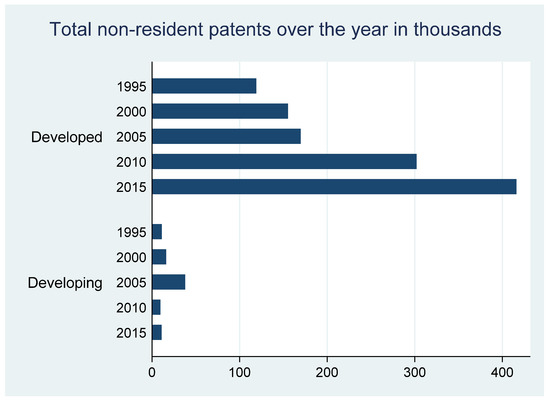

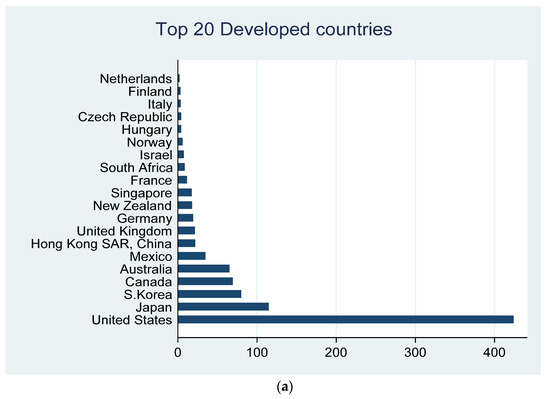

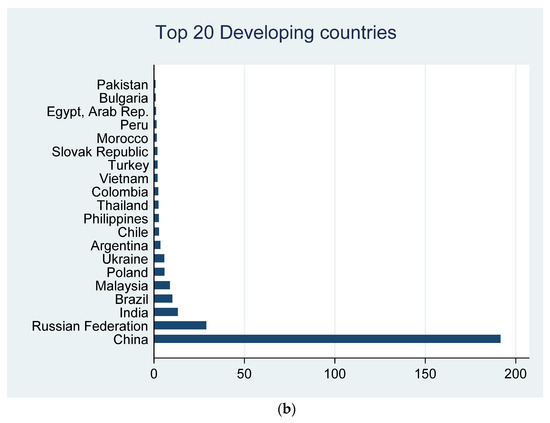

Furthermore, we compare total non-resident patents over the years for developed and emerging country groups in Figure 3. There is an apparent gap in contribution to global innovation between developed and emerging countries. While the innovation over the years is rapidly increasing for the developed countries, it is stagnant for the emerging countries which is very concerning. We report the Top 20 inventive countries for both developed and emerging country groups in Figure 4a,b, respectively. There is a wide range of heterogeneity across countries within each group. The Top 5 contributors to global innovation are U.S., Japan, South Korea, Canada, and Australia in the developed country group and China, Russia, India, Brazil, and Malaysia in the emerging country group.

Figure 3.

Non-resident patents over the year by Developed and Emerging Countries.

Figure 4.

Top 20 non-resident patents producers by Developed and Emerging countries (in thousands). (a) shows the non-resident patents by top 20 developed counties. (b) shows the non-resident patents by top 20 emerging counties.

When people immigrate to another country, it is most likely that they consciously choose which countries they might live in for the rest of their lives. Particularly, creative people who have big dreams in life might pick a country where the likelihood of actualization of their ideas is high (Akcigit et al. 2017). Without proper handling of such unobservable self-selection, the issue could bias our results and could pick up spurious correlations. To mitigate the issue, we balance our sample using the propensity matching technique by Rosenbaum and Rubin (1983) and report our results in the robustness tests.

Furthermore, in our baseline analyses, although the dependent and independent variables vary by host-home country and year match, the host country control and year fixed effects are repeated for the same host and the time causing potential correlations in error terms. In addition, one may argue that when both immigration and innovation rates are separated by each country of origin, the results can be driven by the large sample size. To address the issue, we aggregate both the number of immigration and the number of non-resident patents at the host country level. As a result, our sample size drops significantly from 5042 host-home-year observations to 407 host-year observations only for the full sample. We report the results in robustness tests’ section.

3.2. Model Development

In order to test the effect of immigration on innovation, we develop a model that links immigration to patent rate similar to Ozgen et al. (2012)’s basic model framework as below:

where i is a host (destination), and j is a home (origin) country indicators, and t is a time subscript. Burchardi et al. (2020) documented heterogeneity at the local level and highlighted the importance of segregated data rather than aggregate data at the host country level. Therefore, our dependent variable is the number of non-resident patents at i country registered by the inventors from j country’s origin at time t scaled by the host country’s population per million people. A key interested variable is the immigration rate. We compute the immigration rate as the number of immigrant stock to i country coming from j country at time t scaled by the host country’s population per thousand people. The above measures are consistent with the literature on innovation and immigration (Beine et al. 2008; Docquier and Rapoport 2012; Naghavi and Strozzi 2015). Therefore, the coefficient of interest is β1, and we expect a significant positive value for an emerging country subsample to support Hypothesis 1. In addition, the coefficient estimates for β1 must be statistically significantly different for emerging and developed country subsamples to support Hypothesis 2.

Our choice of control variables is consistent with the literature to include various host country’s resources to facilitate and promote innovation. We include education, net export, GDP per capita, remittances, and population. R&D investment is shown to be an important factor for innovation (Das et al. 2020). Similarly, Peri (2009) documents that R&D spending tends to attract high-skilled immigrants to the host country. Therefore, we add R&D expense as a control variable. In addition, having an open policy to attract MNEs shown to contribute to the host country’s innovation (Goldberg et al. 2011; Liu et al. 2010). We include FDI, and the country’s openness index as well. We explain how we measure and construct each variable in Appendix A.

4. Results

4.1. Baseline Results

Table 3 presents our results from the baseline multiple regression analyses. Column 1 presents the results from the full sample. We find that on average when the number of immigrants from a certain home country to a certain host country increases by 1000 per 1 million population of the host, the number of non-resident patents from the same home country origin increases by about 100 per 1 million population.

Table 3.

Baseline results. This table reports the results from the OLS regression analyses. Column 1 shows the regression results for the entire sample. Columns 2 and 3 report the results for the emerging and developed market groups, respectively. The dependent variable is the non-resident patent rate and the main independent variable is the immigration rate. The standard errors are robust, and p-values are in the brackets below. Statistical significances are represented by *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1, respectively.

The coefficient estimate is positive 0.10 and statistically significant at 5 percent. Most of the control variables remain significant with few exceptions. Particularly, we find that an increase in education rate, R&D expense, GDP per capita, and the degree of host country’s openness promotes innovation by non-residents. On the contrary, the population and the remittances adversely impact the innovation rate.

In Table 3, Columns 2 and 3, we present results from emerging, and developed country groups, respectively. While 14.3 percent of our sample belongs to the emerging country groups, 85.7 percent of the sample belongs to the developed country groups. As shown, we see a significant positive impact of the immigration rate on innovation for both country groups. More specifically, we find that an increase in the immigration rate by 1000 people per 1 million population will result in an increase of 20 non-resident patents per 1 million population for emerging countries supporting our Hypothesis 1. The result is consistent with Aldieri et al. (2020) which focuses on Russia. Our results imply that the positive effect can be applicable to the other emerging economies too. However, the same number of an increase in immigration per 1 million population will lead to about 110 more patents by the non-residents per 1 million population in a developed country, implying there is an unequal gain from immigration to the degree of innovation for an emerging versus a developed country. The coefficient estimates are statistically significantly different at 7 percent. A brain gain for a developed host country is approximately 5.5 times bigger than that of an emerging host country in support of our Hypothesis 2.

4.2. Sensitivity to Immigrant’s Types

Evidence suggests that skilled immigrants bring values to the human capital of the host countries, and contribute most to innovation and productivity (Bosetti et al. 2012; Hunt and Gauthier-Loiselle 2010; Kerr and Lincoln 2010). In an emerging country context, Aldieri et al. (2020) found a significant positive impact of skilled immigrants’ contribution to the innovation and R&D expenditures. We proxy immigrants’ skills and creativities, based on their country of origin’s relative education level and the R&D expenditures. It is very common to use the degree of education to proxy relative skills (Blit et al. 2020; Das et al. 2020; Peri et al. 2015). Therefore, we identify immigrants as skilled if their home country education rates are above our sample median, or unskilled otherwise, and create a dummy variable for it. Next, we interact the immigration rate with the skilled dummy and introduce it to our baseline equation. Table 4 presents our results to the sensitivity of skilled immigrants.

Table 4.

This table shows the heterogeneity of our results to the immigrants’ skills. We proxy immigrants’ skills by their country of origin’s relative education level. We create a skilled dummy which takes a value of one if the home country’s education rate is above sample median value, and zero otherwise. Column 1 shows the regression results for the entire sample. Columns 2 and 3 report the results for the emerging and developed market groups, respectively. The dependent variable is the non-resident patent rate and the main interested variable is an interaction term between immigration rate and the skilled dummy. The standard errors are robust, and p-values are in the brackets below. Statistical significances are represented by *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1, respectively.

Table 4, Column 1 presents our results from the full sample. The skilled dummy alone adversely impacts on non-resident patents of the host country. It might be because a high skill/education in a home country discourages immigration, so does the application of patents in another country. While the coefficient estimate for the immigration rate remains positively significant, the coefficient estimate for the interacted term is also positively significant and economically twice as much as the immigration rate. In other words, the brain gain is much greater for skilled immigrants as compared to unskilled ones. An increase of skilled immigrants by 1000 per 1 million population would result in 240 more non-immigrant patents per 1 million population as compared to unskilled immigrants. The coefficient estimate for the interaction term is statistically significant at 5 percent, while the control variables remain consistent with the same signs as in the baseline.

In Table 4, Column 2 and 3, we compare our results from emerging and developed country groups. After introducing the interaction term, neither the immigration rate nor the interaction term is significant for the emerging countries. The results imply that there is no significant difference in terms of their contribution to innovation among skilled versus unskilled immigrants coming to emerging countries.

It might be due to a lack of resources, intellectual property rights protection, proper institutions, facilities, and policies in place to promote skilled immigrants. Furthermore, there has been some argument that says while immigrant entrepreneurs in emerging countries are needs-driven, immigrant entrepreneurs in the developed countries are opportunity-driven (Elo 2016). Our findings are consistent with it. For the developed country sample in Column 3 on the contrary, we find much stronger and statistically significant coefficients. Developed host countries are equipped with significantly more resources, open policies for equal opportunities, and facilities for the advantage of skilled immigrants who are in search of the best opportunities. Therefore, the brain gains for developed countries seem to be much stronger and significant. The results imply that the states of the host country play significant roles in brain gains.

We find very similar and consistent results for creative immigrants. We use R&D expenditure in the home country to proxy the creativity. We argue that immigrants who are coming from an environment that recognizes innovation and invests in R&D heavily, tend to be more innovation-oriented. Therefore, they could contribute to the host country’s innovation more. We create an inventive dummy that takes a value of one for immigrants whose home country’s R&D expenditure is above the sample median and zero otherwise. Like previous analyses, we introduce an interaction term between the immigration rate and the inventive dummy. We report our results in Table 5. Column 1 presents results from full, Column 2 presents results from emerging, and Column 3 presents results from developed country samples respectively.

Table 5.

This table shows the heterogeneity of our results to the immigrants’ creativity. We proxy immigrants’ creativity by their country of origin’s relative R&D expenditures. We create an inventive dummy which takes a value of one if the home country’s R&D expenditure rate is above sample median value, and zero otherwise. Column 1 shows the regression results for the entire sample. Columns 2 and 3 report the results for the emerging and developed market groups, respectively. The dependent variable is the non-resident patent rate and the main interested variable is an interaction term between immigration rate and the inventive dummy. The standard errors are robust, and p-values are in the brackets below. Statistical significances are represented by *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1, respectively.

The home country’s R&D expense rate is both negative and not-significant on the host country’s innovation. Interestingly, after introducing the interaction term to the equation, the immigration rate is no longer significant, but the interaction term in all sample specifications as shown in Column 1. The inventive immigrants bring more value to the host. An increase of 1000 innovation-oriented immigrants per 1 million population, translates into 300 more non-resident patents per 1 million population of the host country as compared to other immigrants. The coefficient estimate for the interaction term is three times greater than the coefficient estimate for the immigration rate in baseline results and statistically significant at 1 percent.

When we split the sample by emerging and developed country groups, we find significantly different results. After introducing the above variables, the coefficient estimates for the emerging countries’ loss significances as shown in Column 2. We find no differences for inventive versus other immigrants. There seems to be no competitive advantage for these innovation-oriented citizens in an emerging country as compared to their less innovation-oriented counterparties. However, when they switch their destination from an emerging to a developed country, they could benefit more from its open policies for innovation, and contribute to the number of non-resident patents. The results are consistent with Enkhtaivan and Davaadorj (2020)’s argument that emerging countries need to be responsive to global dynamism to change their openness policies. The coefficient estimate for the interaction term is 0.46 and significant at 1 percent. An increase of 1000 innovation-oriented immigrants (per 1 million population of the host country) contributes to 460 more patents as compared to their less innovation-oriented counterparties when they land in a developed host country. Immigrants coming from high R&D invested home countries might be more self-motivated, and in search of know-how to begin with. When they change their environment to live in a developed country, they tend to contribute to the host country’s innovation more.

Results from Table 4 and Table 5 suggest multiple implications for practice. First, the states of the country of origin for immigrants are heterogeneous, thus have different implications on the host country’s innovation rate. Second, the state of the host country’s economy seems to determine whether there would be an actualization of brain gain or not. Third, the current data show strong positive brain gains from immigrants coming from high education and high R&D invested home countries. However, when the sample is split for emerging and developed groups, the results are driven by the developed countries only and not significant for emerging countries. Naghavi and Strozzi (2015) highlighted the role of intellectual property rights in brain gains from migration for an emerging country. We agree with their conclusion. To reduce the gap in brain gains from immigration, and become more competitive, emerging countries need to implement policies to attract more skilled, innovation-oriented people to their countries, at the same time, supply necessary resources and equal opportunities for them.

4.3. Sensitivity to Different Sub-Samples

From Table 1, we see that immigration is neither randomly nor uniformly distributed for home and host countries. While certain destinations attracting more immigrants may be due to their living amenities, equal opportunities, and more open policies, certain countries of origin tend to lose more of their human capital to other countries (Desmet et al. 2018). Burchardi et al. (2020) documented that high-skilled people tend to be mobile, selectively choose where to go, pick the hottest destination and urban areas for prosperity for their families within the U.S. For such non-random choices, results might be driven by certain samples and could be biased. Next, we test the sensitivity of our results to the Top 10 destination and Top 10 origin countries.

In Table 6, Columns 1 and 2, we compare the Top 10 destinations to the other host country groups. While 25 percent of the sample immigrants choose to go to Top 10 destination countries, the remaining 75 percent immigrated to other countries. When we split the sample, the immigration rate remains positive and statistically significant on the innovation rate for both samples. However, in terms of economic significance, Top 10 host countries listed in Table 1, seem to benefit almost 5.6 times as much as other countries. While an increase by 1000 immigrants to these Top 10 countries per 1 million population results in 390 more non-resident patents per 1 million population, the rest of the host countries results in only 70 more non-resident patents. The difference in the above coefficient estimates is statistically significant at less than 1 percent. The results suggest that it could be since Top 10 destinations for immigration might attract the most talented global workforce because of their popularity, as such, the benefits from brain gains are much higher than the others.

Table 6.

This table shows the sensitivity of our results to various subsamples. Columns 1 and 2 report the results for the Top 10 versus non-Top 10 destination countries. Columns 3 and 4 report the results for the Top 10 versus non-Top 10 origin countries. The dependent variable is the non-resident patent rate and the main independent variable is the immigration rate. The standard errors are robust, and p-values are in the brackets below. Statistical significances are represented by *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1, respectively.

In Table 6, Columns 3 and 4, we compare the Top 10 country of origin versus other country groups. While 18.9 percent of the immigrants are coming from the Top 10 country of origin, the remaining 81.1 percent of the immigrants are coming from the rest of the world. Desmet et al. (2018) argued that due to the high cost associated with immigration, it is not a choice for everyone. In Columns 3 and 4, the coefficient estimate for immigrant rate remains positive and statistically significant at 1 percent for both sub-samples. However, the economic significance is very different for the two subsamples. While an increase of immigrants by 1000 per 1 million host country’s population translates into an increase in non-resident patents by 60 per 1 million population only if the immigrants are coming from Top 10 country of origin, the rest of the world contributes an increase of 530 more non-resident patents per 1 million population. The coefficient estimates are statistically different at 2 percent of significance. The results imply that countries that are losing more of their citizens to other countries are most likely be in worse living conditions, lack of resources, and income. Therefore, people migrating from such environments might not necessarily be equipped with skills or ideas that can contribute to the host country’s innovations as compared to other immigrants coming from the rest of the world.

4.4. Robustness Tests

4.4.1. Addressing Endogeneity Issue

Thus far, in our analyses, we treat immigration as an exogenous shock. Countries in an attempt to attract the most talented human capital in today’s increasingly global world might promise various benefits and equal opportunities for everyone. If that is the case, it might be the progressive immigration policies and the current number of innovations that determine the immigration rate, but not the immigration impacting the innovation causing an issue of reverse causality. Furthermore, missing some significant variables that impact the innovation from the analyses could bias the results. Furthermore, ample evidence in a single country (Hunt and Gauthier-Loiselle 2010; Moser et al. 2014) or in multiple countries (Beine et al. 2008; Ozgen et al. 2012; Peri 2009) settings suggests immigration is indeed endogenous. Therefore, to address potential endogeneity issues, we introduce some instrument variables and conduct two-stage regression analyses.

The literature on immigration uses the home country’s economic, demographic, and social variables as push-factor instruments (Burchardi et al. 2020; Ortega and Peri 2009). We introduce the home country’s income per capita, education rate, and population as instruments on immigration rate to estimate its exogenous value in the first stage regression. Next, using the predicted value, we run the second stage regression on innovation rate. We report the results from 2SLS in Table 7. Columns 1 and 2 report results from the first and the second stage regressions for the full sample. As shown, the home country’s income per capita and population indeed impact the immigration rate to a host country. From the second stage results in Column 2, the significance of the immigration rate becomes stronger not only economically, but also statistically. The endogeneity test statistics show that the immigration rate is endogenous, and it is appropriate to use the above instruments for the analyses. F-test for the joint significance of the instruments is rejected at less than 1 percent showing they are strong instruments.

Table 7.

This table reports the results from the 2SLS regression analyses. We use push-factor home country variables such as income per capita, education rate, and population as instruments. Columns 1 and 2 report results from the full sample, Columns 3 and 4 report results from the emerging, and Columns 5 and 6 report results from the developed country groups respectively. The dependent variable is the non-resident patent rate and the main independent variable is the predicted immigration rate estimated from the first stage regressions. The standard errors are robust, and p-values are in the brackets below. Statistical significances are represented by *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1, respectively. We test the strength, identification, and validity of the instruments and report the results at the bottom of the table.

In addition, overidentification tests cannot be rejected, implying the instruments are sufficiently uncorrelated with the error term. In fact, for all other subsample specifications, both emerging and developed country groups, the above instruments are shown to be appropriate, strong, and valid. Therefore, we conclude that even after addressing the endogeneity issue, our results still support the presence of brain gains for emerging countries as assumed in Hypothesis 1.

Although the statistical significance drops from 1 percent to 10 percent in the emerging country subsample, the economic significance is stronger. After addressing the endogeneity issue, an increase of immigration by 1000 per 1 million population at a host country can promote innovation, so that the number of non-resident patents per 1 million population can increase by 3780 for an emerging country. The same level of immigration rate can lead to an even higher innovation rate, 6260 non-resident patents per 1 million population at a developed host country. Results for the developed country subsample in Columns 5 and 6 show that the coefficient estimate for the immigration rate remains both economically and statistically stronger, and almost twice as much as impactful than the emerging country sample. Therefore, we conclude that after addressing the endogeneity problem, the results show a brain gain gap between emerging and developed countries further supporting our Hypothesis 2.

4.4.2. Addressing Self-Selection Issue

We create a treated group for immigrants coming from highly educated countries (our proxy for skilled immigrants) and choose to live in Top 10 destinations (our proxy for host countries that offer the most open policies and equal opportunities). We identify 1616 observations as the treated group, and consider the rest of the sample as a control group. We compute propensity scores for both treated and control groups using the logit model, the likelihood of being a treated group based on host country’s R&D expense, GDP per capita, and openness index. We then match each observation in the treated group with an observation in the control group based on their propensity scores to create a balanced sample of 1021 observations.

We report our results from the analyses in Table 8. After addressing the self-selection issue by using propensity score matching, the coefficient estimates for the immigration rate is significantly positive at 1 percent and economically stronger. In Column 1, we see that as the number of immigrants per 1 million population increases by 1000, the number of non-resident patents increases by about 550 per 1 million population. Furthermore, the coefficient estimates for the immigration rate from emerging and developed countries subsamples in Columns 2 and 3, still show a significant difference. The brain gain is driven mostly by the developed host countries. The benefits to the developed country are more than 32 times higher than that of the emerging countries. While an increase of immigrants per 1 million population by 1000 contributes to 970 new non-resident patents in the developing countries, the same level of immigration rate can only result in 30 new non-resident patents in the emerging countries. Our empirical results consistently show a significant gap in brain gains between developed versus emerging countries in support of Hypothesis 2.

Table 8.

This table reports the results after addressing the potential self-selection issue. We create a balanced sample using the propensity score matching technique. The treated group consists of skilled immigrants who live in Top 10 destination countries, and the control group is the rest of the sample. We match the two groups based on their propensity scores without replacement within a caliper of 0.05. Column 1 shows the regression results for the entire sample. Columns 2 and 3 report the results for the emerging and developed market groups, respectively. The dependent variable is the non-resident patent rate and the main independent variable is the immigration rate. The standard errors are robust, and p-values are in the brackets below. Statistical significances are represented by *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1, respectively.

4.4.3. Addressing Large Sample Bias

Table 9 reports our robustness test results after addressing the potential large sample bias. We see significant improvements in our results across all sample specifications. In Column 1, the coefficient estimate for the total immigration rate increases from 0.10 to 4.79 as compared to the baseline. The statistical significance improves from 5 percent to 1 percent. Most importantly, the overall explanatory power of the model indicated by the R-square also improves significantly to 73 percent. Therefore, after addressing potential large sample bias, our results support Hypothesis 1. The emerging and developed country groups still show significant brain gain gap. The benefits to the developed world are about 3.6 times higher than that of the emerging countries which are statistically significantly different at less than 1 percent. The results further support our Hypothesis 2.

Table 9.

This table reports the regression results after addressing potential large sample bias. We aggregate the number of non-resident patents and the immigration at the host country level before finding the respective rates. As a result of this conversion, our data change from host-home-year to host-year observations with a single observation per host country for each year. Column 1 shows the regression results for the entire sample. Columns 2 and 3 report the results for the emerging and developed market groups, respectively. The dependent variable is the non-resident patent rate and the main independent variable is the immigration rate. The standard errors are robust, and p-values are in the brackets below. Statistical significances are represented by *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1, respectively.

5. Conclusions

Brain gains for developed countries due to immigration have been explored extensively, yet there has not been much explored for emerging countries. Who are the immigrants to emerging countries, and how much gains they bring to the host country in comparison to the developed countries are not well understood. In a cross-country context, over the last two decades, we find the presence of brain gains for emerging countries. However, there is still a significant gap in brain gains when compared to developed countries. The estimated gap is about 5.5 times higher for developed countries exacerbating the inequality between the two groups. Our data show that the migration rate fleeing out of emerging countries is much higher than their immigration rate and increasing over time. Moreover, one of the reasons for a gap in brain gains is emerging countries seem not to fully utilize their skilled and inventive immigrants. We find no significant difference between the above-talented immigrant pool versus unskilled immigrants coming to the emerging countries. Innovations by non-residents in emerging countries seem to be driven by needs for survival mostly, thus not competitive enough to fill the brain gain gap. There are no special treatments to adequately protect intellectual properties, promote inventive thinking, and attract global talents to the emerging countries.

Our findings have policy implications for emerging countries’ development and human capital sustainability. Evidence from China suggests that immigration does not have a zero-sum game (Kerr 2008; Liu et al. 2010). With progressive policies on MNEs’ entry, and open policies for the migrant returns, their ties to home, collaborations on innovations can accelerate the growth and bring values for the home countries too. For immigrant inflows, selective screening of skilled people, and competitive offers seem to pay off. Generous benefits and amenities for lives tend to attract international mobile talents. However, to harvest the full benefits, it is also important to provide resources and facilitate a healthy environment to nurture innovations.

Our study is not free from flaws. The representation of emerging countries in our sample is limited to the countries that report their non-resident patents to the WIPO for the observed years. Due to our data restriction, we could not directly identify individual immigrant’s background information, rather we use proxy estimates. Our study does not differentiate brain gains due to international collaborations which have become increasingly common. It is fruitful to explore brain-sharing among countries. A future study with an emphasis on emerging countries would be helpful.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.E. and Z.D.; methodology, B.E. and Z.D.; formal analysis, B.E. and Z.D.; investigation, Z.D.; data curation, B.E. and Z.D.; writing—original draft preparation, B.E; writing—review and editing, J.B. and Z.D.; supervision—J.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

This table shows the data sources for variables we use in this study.

| Variables | Definition | Source |

| Non-resident patent rate | The number of non-resident patents per 1 million population | World International Property Organization |

| Immigration rate | The number of immigrants per 1 thousand population | United Nations |

| Education | The number of secondary school enrollment per population | World Bank |

| R&D expenditure | Percent of research and development expenditure in GDP | World Bank |

| Net Export | Next export to GDP ratio | World Bank |

| Net FDI | Net FDI inflow to GDP ratio | World Bank |

| GDP per cap | GDP per capita in current thousand USD | World Bank |

| Remittances | Remittances to GDP ratio | World Bank |

| Population | Natural logarithm of total population | World Bank |

| Openness Index | Country’s openness index | Heritage Foundation |

References

- Aghion, Philippe, and Peter Howitt. 1992. A Model of Growth Through Creative Destruction. Econometrica 60: 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akcigit, Ufuk, John Grigsby, and Tom Nicholas. 2017. The Rise of American Ingenuity: Innovation and Inventors of the Golden Age. National Bureau of Economic Research. Available online: https://www.nber.org/papers/w23047 (accessed on 16 November 2020).

- Aldieri, Luigi, Maxim Kotsemir, and Concetto Paolo Vinci. 2020. The Role of Labour Migration Inflows on R&D and Innovation Activity: Evidence from Russian Regions. Foresight 22: 437–68. [Google Scholar]

- Alesina, Alberto, and Eliana La Ferrara. 2005. Ethnic Diversity and Economic Performance. Journal of Economic Literature 43: 762–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anokhin, Sergey, and Joakim Wincent. 2012. Start-up Rates and Innovation: A Cross-Country Examination. Journal of International Business Studies 43: 41–60. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1057/jibs.2011.47 (accessed on 19 November 2020).

- Beach, Charles M., Alan G. Green, and Christopher Worswick. 2007. Impacts of the Point System and Immigration Policy Levers on Skill Characteristics of Canadian Immigrants. Research in Labor Economics 27: 349–401. [Google Scholar]

- Beine, Michel, Fréderic Docquier, and Hillel Rapoport. 2008. Brain Drain and Human Capital Formation in Developing Countries: Winners and Losers. The Economic Journal 118: 631–52. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/ej/article/118/528/631-652/5089483 (accessed on 23 November 2020). [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, Shai, Rebecca Diamond, Timothy Mcquade, and Beatriz Pousada. 2019. The Contribution of High-Skilled Immigrants to Innovation in the United States. Working Papers. Available online: https://econ.tau.ac.il/sites/economy.tau.ac.il/files/media_server/Economics/PDF/seminars%202019-20/BDMP_2019.pdf (accessed on 16 November 2020).

- Blit, Joel, Mikal Skuterud, and Jue Zhang. 2020. Can Skilled Immigration Raise Innovation? Evidence from Canadian Cities. Journal of Economic Geography 20: 879–901. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/joeg/article/20/4/879/5637831 (accessed on 16 November 2020). [CrossRef]

- Bosetti, Valentina, Cristina Cattaneo, and Elena Verdolini. 2012. Migration, Cultural Diversity and Innovation: A European Perspective. Working Papers. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/p/igi/igierp/469.html (accessed on 16 November 2020).

- Bratti, Massimiliano, and Chiara Conti. 2018. The Effect of Immigration on Innovation in Italy. Regional Studies 52: 934–47. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00343404.2017.1360483 (accessed on 18 November 2020).

- Burchardi, Konrad, Thomas Chaney, Tarek Alexander Hassan, Lisa Tarquinio, and Stephen J. Terry. 2020. Immigration, Innovation, and Growth. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research. Available online: http://www.nber.org/papers/w27075.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2020).

- Clarke, Andrew, Ana Ferrer, and Mikal Skuterud. 2019. A Comparative Analysis of the Labor Market Performance of University-Educated Immigrants in Australia, Canada, and the United States: Does Policy Matter? Journal of Labor Economics 37: S443–S490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crescenzi, Riccardo, and Alexander Jaax. 2017. Innovation in Russia: The Territorial Dimension. Economic Geography 93: 66–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, Gouranga Gopal, Sugata Marjit, and Mausumi Kar. 2020. The Impact of Immigration on Skills, Innovation and Wages: Education Matters More than Where People Come From. Journal of Policy Modeling 42: 557–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, Sally, and David Bibby. 1999. Rethinking a National Innovation System: The Small Country as ‘SME. ’ Technology Analysis and Strategic Management 11: 431–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmet, Klaus, Dávid Krisztián Nagy, and Esteban Rossi-Hansberg. 2018. The Geography of Development. Journal of Political Economy 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Docquier, Frédéric, and Hillel Rapoport. 2012. Globalization, Brain Drain, and Development. Journal of Economic Literature 50: 681–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elo, Maria. 2016. Typology of Diaspora Entrepreneurship: Case Studies in Uzbekistan. Journal of International Entrepreneurship 14: 121–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enkhtaivan, Bolortuya, and Zagdbazar Davaadorj. 2020. An Integrated-Dynamic Mode of Entry Model: Global MNEs Entering into Emerging Markets. Review of International Business and Strategy 30: 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, Itzhak, John Gabriel Goddard, Smita Kuriakose, and Jean-Louis Racine. 2011. Igniting Innovation. Washington: The World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Grubel, Herbert B. 1966. The International Flow of Human Capital. The American Economic Review 56: 268–74. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, Jennifer, and Marjolaine Gauthier-Loiselle. 2010. How Much Does Immigration Boost Innovation. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 2: 31–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Charles I. 1995. R & D-Based Models of Economic Growth. Journal of Political Economy 103: 759–84. [Google Scholar]

- Kerr, Sari Pekkala, and William Kerr. 2020. Immigrant Entrepreneurship in America: Evidence from the Survey of Business Owners 2007 & 2012. Research Policy 49: 103918. [Google Scholar]

- Kerr, William R. 2008. Ethnic Scientific Communities and International Technology Diffusion. Review of Economics and Statistics 90: 518–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, William R. 2019. The Gift of Global Talent: How Migration Shapes Business, Economy & Society—William R. Kerr—Google Books. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kerr, William R., and William F. Lincoln. 2010. The Supply Side of Innovation: H-1B Visa Reforms and U.S. Ethnic Invention. Journal of Labor Economics 28: 473–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzior, Aleksandra, Anna Liakisheva, Iryna Denysiuk, Halyna Oliinyk, and Liudmyla Honchar. 2020. Social Risks of International Labour Migration in the Context of Global Challenges. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 13: 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Xiaohui, Jiangyong Lu, Igor Filatotchev, Trevor Buck, and Mike Wright. 2010. Returnee Entrepreneurs, Knowledge Spillovers and Innovation in High-Tech Firms in Emerging Economies. Journal of International Business Studies 41: 1183–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayda, Anna Maria. 2010. International Migration: A Panel Data Analysis of the Determinants of Bilateral Flows. Journal of Population Economics 23: 1249–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, Lili, Xiao-Guang Yue, Xue-Feng Shao, Yuanfei Kang, and Yulong Liu. 2020. Strategic Asset Seeking and Innovation Performance: The Role of Innovation Capabilities and Host Country Institutions. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 13: 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, Petra, Alessandra Voena, and Fabian Waldinger. 2014. German Jewish Émigrés and US Invention. American Economic Review 104: 3222–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naghavi, Alireza, and Chiara Strozzi. 2015. Intellectual Property Rights, Diasporas, and Domestic Innovation. Journal of International Economics 96: 150–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathan, Max. 2015. Same Difference? Minority Ethnic Inventors, Diversity and Innovation in the UK. Journal of Economic Geography 15: 129–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, Francesc, and Giovanni Peri. 2009. The Causes and Effects of International Labor Mobility: Evidence from OECD Countries 1980–2005. Human Development Research Paper (HDRP) Series. Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/19183/1/MPRA_paper_19183.pdf (accessed on 16 November 2020).

- Ozgen, Ceren, Peter Nijkamp, and Jacques Poot. 2012. Immigration and Innovation in European Regions. In Migration Impact Assessment: New Horizons. Edited by Peter Nijkamp, Jacques Poot and Mediha Sahin. ICheltenham: Edward Elgar, pp. 261–300. [Google Scholar]

- Peri, Giovanni. 2009. The Determinants and Effects of Highly-Skilled Labor Movements: Evidence from OECD Countries 1980–2005. Working Paper. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Giovanni_Peri/publication/265539843_The_determinants_and_effects_of_highly-_skilled_labor_movements_Evidence_from_OECD_countries_1980-2005/links/563a2ab108ae405111a57e14.pdf (accessed on 16 November 2020).

- Peri, Giovanni, Kevin Shih, and Chad Sparber. 2015. STEM Workers, H-1B Visas, and Productivity in US Cities. Journal of Labor Economics 33: S225–S255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romer, Paul M. 1990. Endogenous Technological Change. Journal of Political Economy 98: 71–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, Paul, and Donald Rubin. 1983. The Central Role of the Propensity Score in Observational Studies for Causal Effects. Biometrika 70: 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vissak, Tiia, and Xiaotian Zhang. 2014. Chinese Immigrant Entrepreneurs’ Involvement in Internationalization and Innovation: Three Canadian Cases. Journal of International Entrepreneurship 12: 183–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Intellectual Property Organization. 2019. World Intellectual Property Report. Geneva: World Intellectual Property Organization. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Authors’ own estimate based on Global Migration data from the United Nations. |

| 2 | A complete list of host and home countries is available upon request. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).