Innovation in SMEs and Financing Mix

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. SMEs and Innovations

RQ1: Are there any contingencies between the types of innovations undertaken by SMEs in the cross-country dimension?

2.2. SMEs and Financing Gap

RQ2: Is there any association between the type of innovations in SMEs and the relevance of a given type of financing?

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results and Discussion

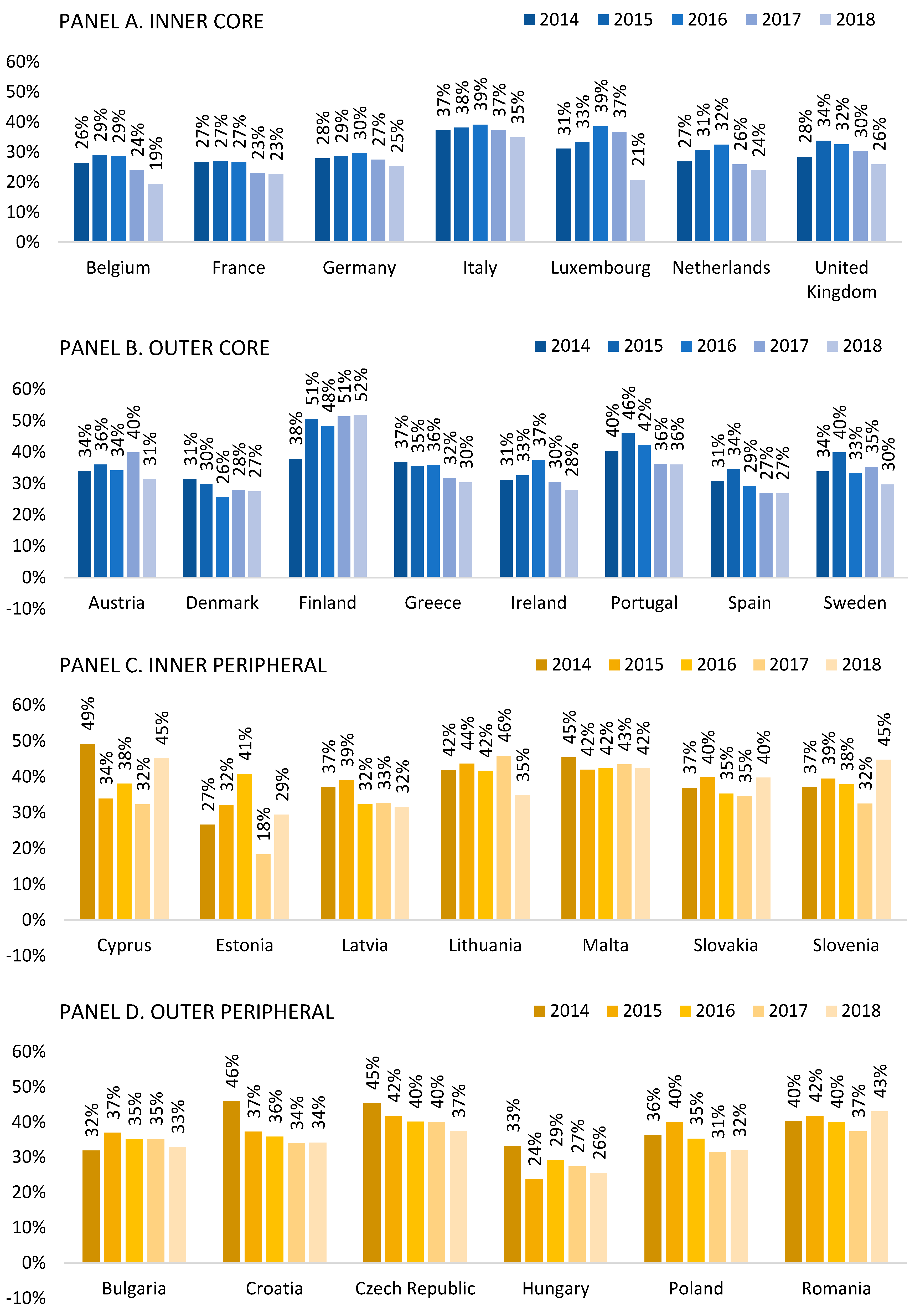

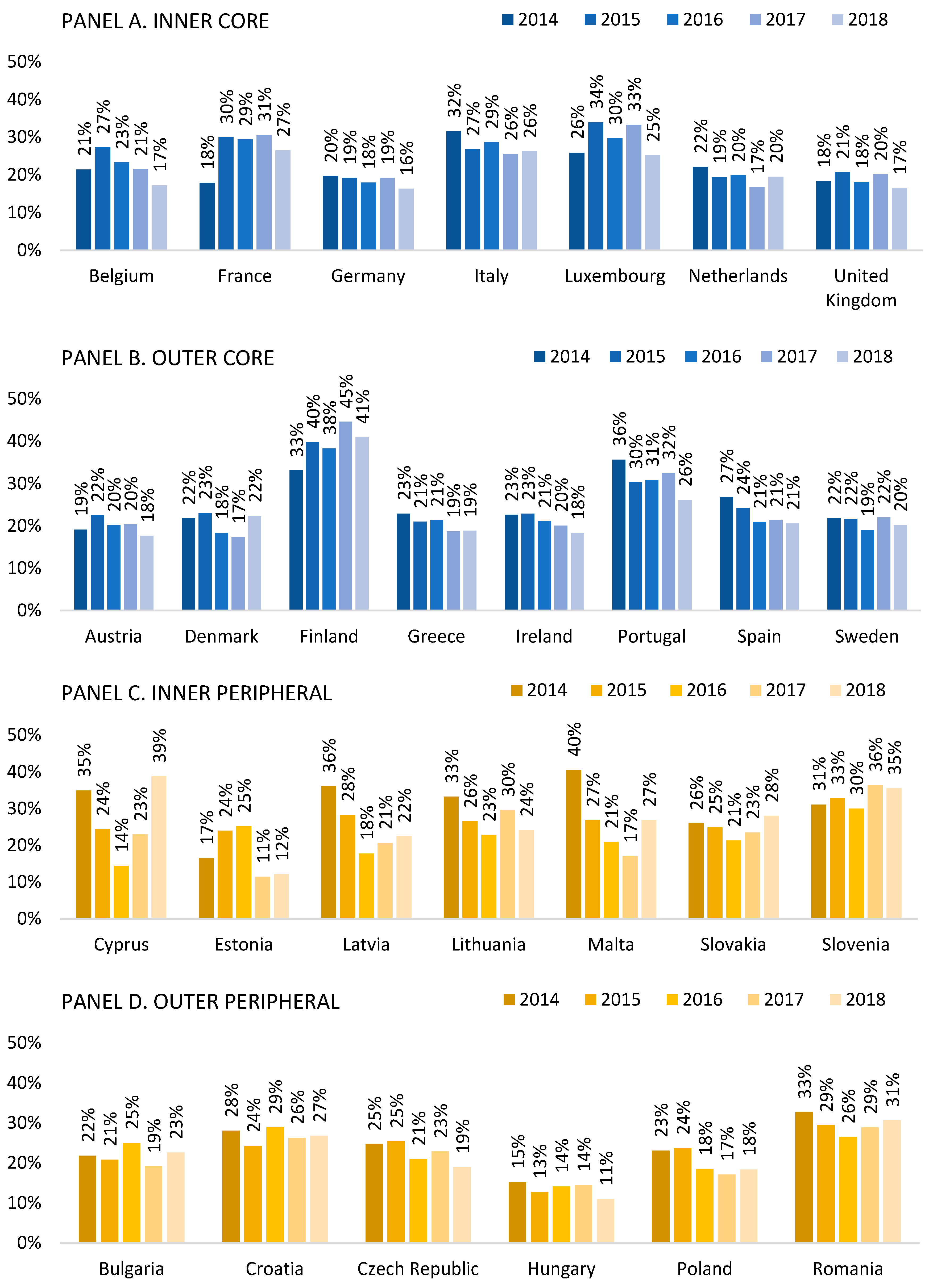

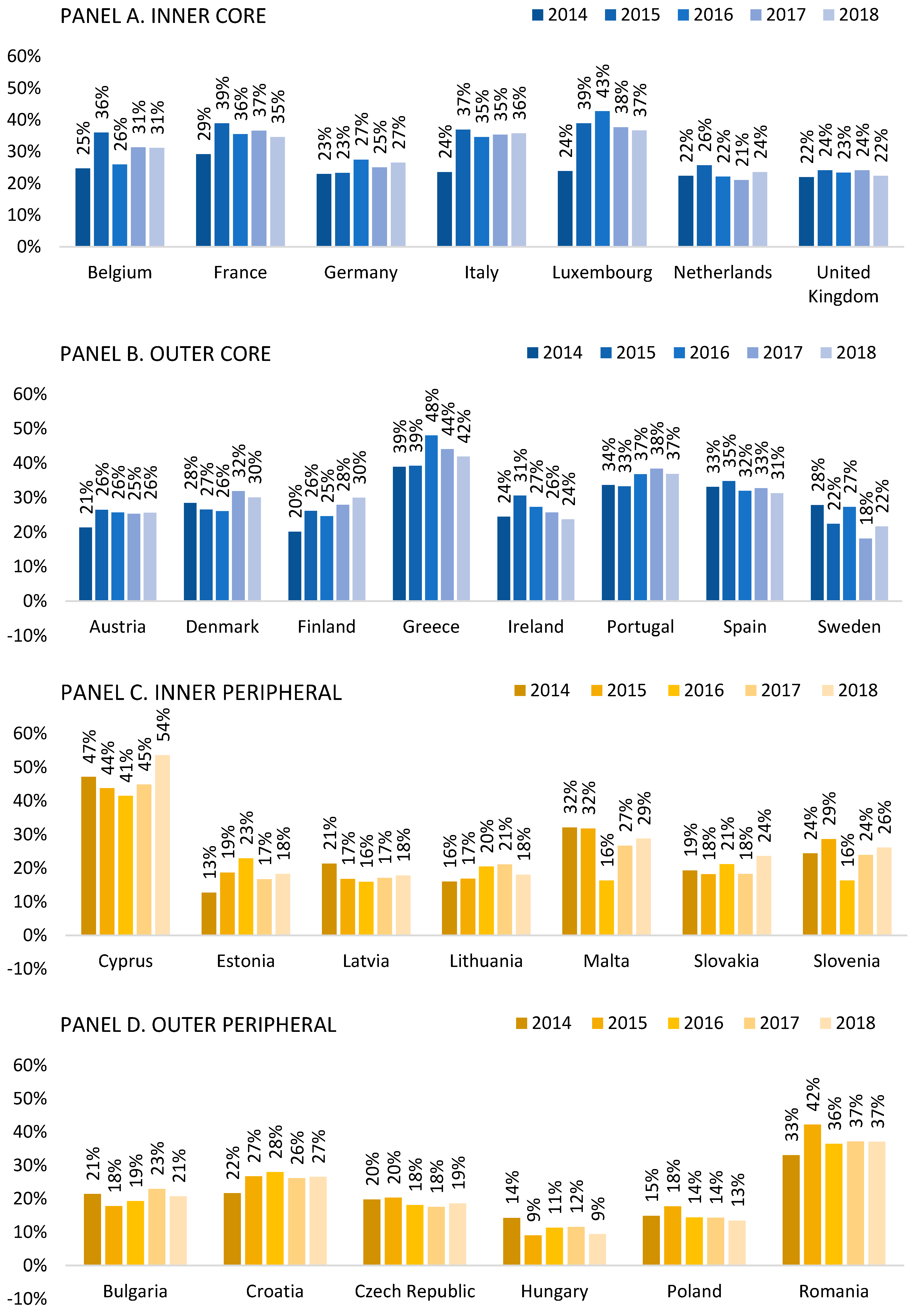

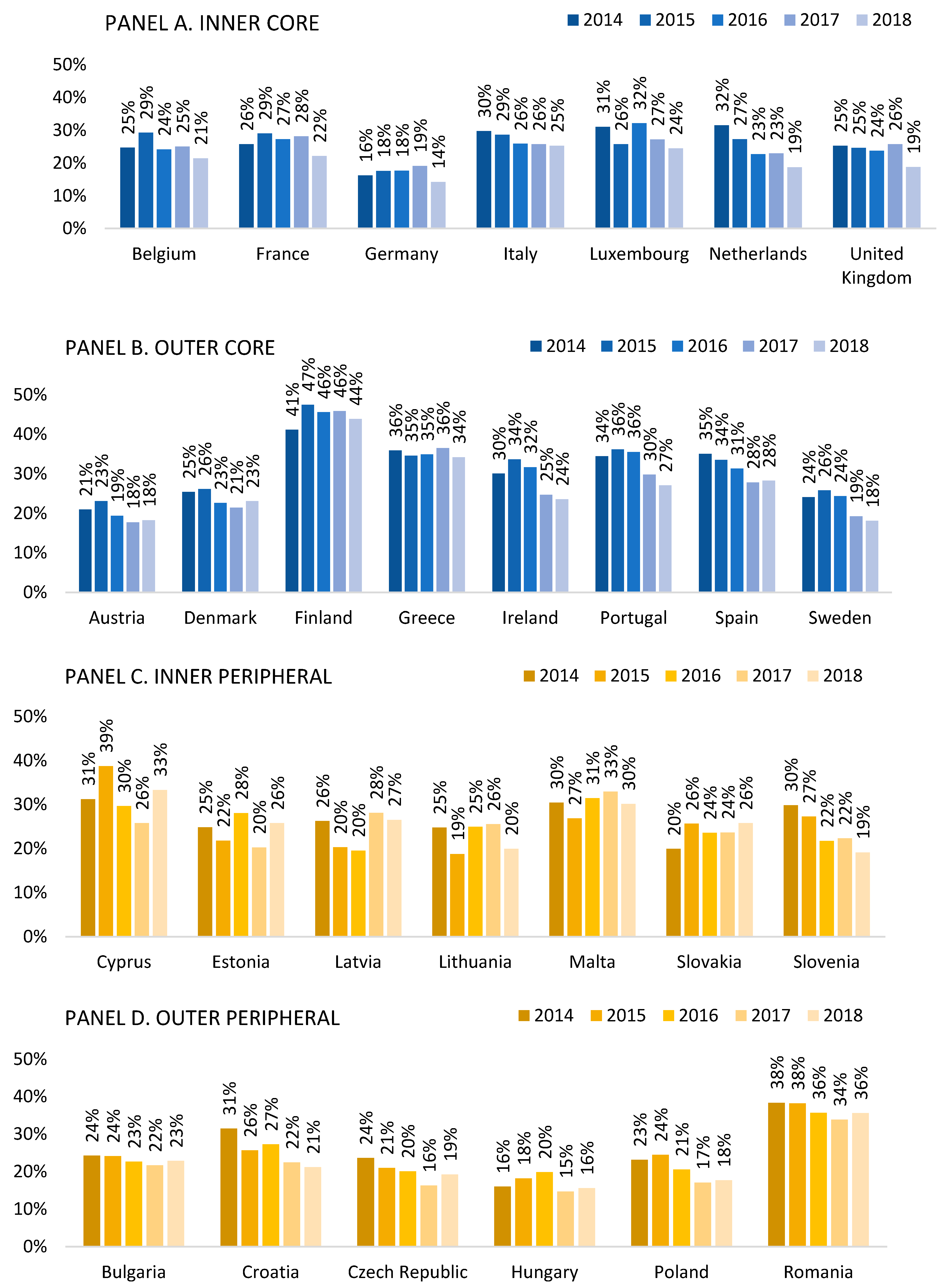

4.1. SMEs Innovations across the EU

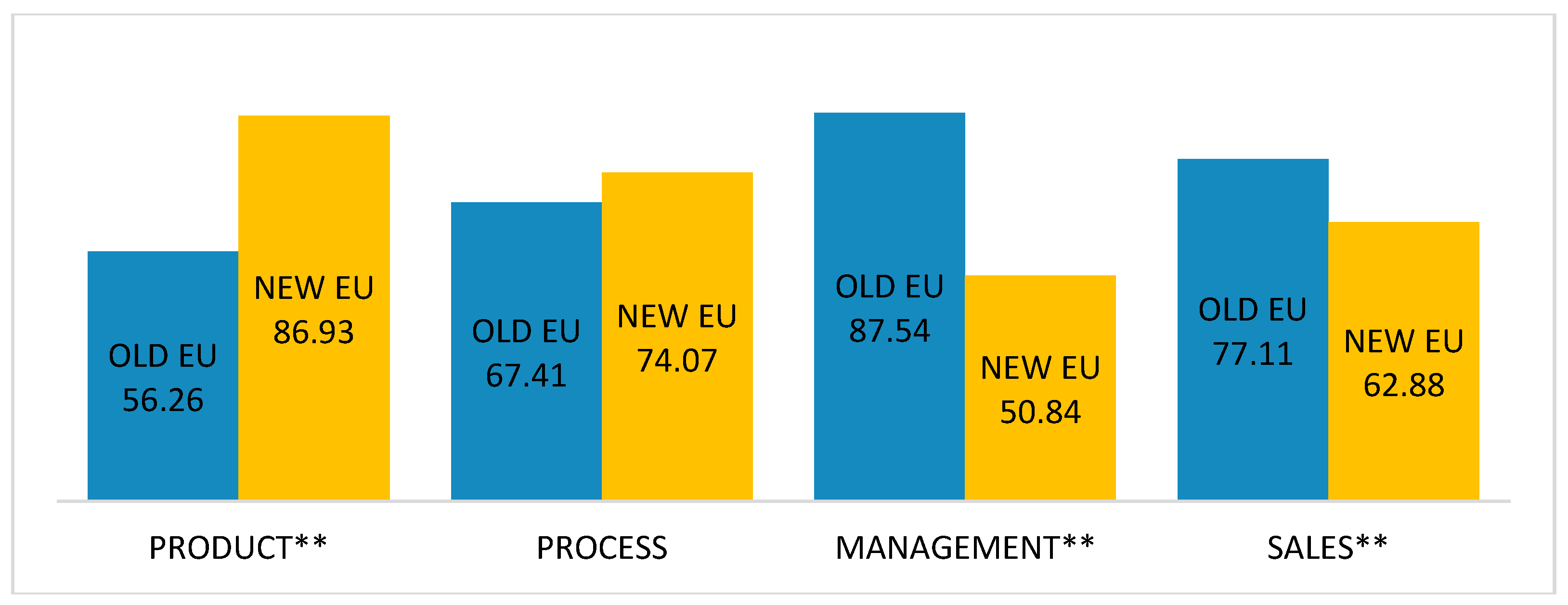

4.2. Types of SMEs Innovations and Sources of Funds

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Angilella, Silvia, and Sebastiano Mazzù. 2015. The financing of innovative SMEs: A multicriteria credit rating model. European Journal of Operational Research 244: 540–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, Muhammad. 2018. Business model innovation and SMEs performance: Does competitive advantage mediate? International Journal of Innovation Management 22: 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assink, Marnix. 2006. Inhibitors of disruptive innovation capability: A conceptual model. European Journal of Innovation Management 9: 215–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avermaete, Tessa, Jacques Viaene, Eleanor J. Morgan, and Nick Crawford. 2003. Determinants of innovation in small food firms. European Journal of Innovation Management 6: 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldock, Robert, and Colin Mason. 2015. Establishing a new UK finance escalator for innovative SMEs: The roles of the Enterprise Capital Funds and Angel Co-Investment Fund. Venture Capital 17: 59–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baregheh, Anahita, Jennifer Rowley, Sally Sambrook, and Dafydd Davies. 2012. Food sector SMEs and innovation types. British Food Journal 114: 1640–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, William, and Ivana Prica. 2017. Interdependence between Core and Peripheries of the European Economy: Secular Stagnation and Growth in the Western Balkans. European Journal of Comparative Economics 14: 123–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, Mita, and Harry Bloch. 2004. Determinants of innovation. Small Business Economics 22: 155–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, Thorsten, Asli Demirguc-Kunt, and Ross Levine. 2005. SMEs, growth, and poverty: Cross-country evidence. Journal of Economic Growth 10: 199–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boer, Harry, and Willem E. During. 2001. Innovation, what innovation? A comparison between product, process and organizational innovation. International Journal of Technology Management 22: 83–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruha, Jan, and Evžen Kocenda. 2018. Financial stability in Europe. Banking and sovereign risk. Journal of Financial Stability 36: 305–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, Massimo G., and Luca Grilli. 2007. Funding gaps? Access to bank loans by high-tech start-ups. Small Business Economics 29: 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Rin, Marco, and MarÃ-a Fabiana Penas. 2007. The effect of venture capital on innovation strategies (No. w13636). National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deffains-Crapsky, Catherine, and Agata Sudolska. 2014. Radical innovation and early stage financing gaps: Equity-based crowdfunding challenges. Journal of Positive Management 5: 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Moor, Lieven, M. Wieczorek-Kosmala, and Joanna Błach. 2016. SME Debt Financing Gap: The Case of Poland. Transformations in Business Economics 15: 274–91. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, Gordon. 1961. Corporate Debt Capacity: A Study of Corporate Debt Policy and Determination of Corporate Debt Capacity. Working Paper. Boston: Harvard Graduate School of Management. [Google Scholar]

- Durvy, Mr Jean-Noel. 2007. Equity Financing for SMEs: The Nature of the Market Failure. In The SME Financing Gap, Proceedings of the Brasilia Conference, Brasilia, 27–30 March 2006. Paris: OECD Publishing, vol. II. [Google Scholar]

- Goujard, Antoine, and Pierre Guérin. 2018. Financing Innovative Business Investment in Poland. OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1480. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, Bronwyn H. 2010. The financing of innovative firms. Review of Economics and Institutions 1: 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, Bronwyn H., Francesca Lotti, and Jacque Mairesse. 2009. Innovation and productivity in SMEs: Empirical evidence for Italy. Small Business Economics 33: 13–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hottenrott, Hanna, and Bettina Peters. 2012. Innovative capability and financing constraints for innovation: More money, more innovation? Review of Economics and Statistics 94: 1126–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hueske, Anne-Karen, and Edeltraud Guenther. 2015. What hampers innovation? External stakeholders, the organization, groups and individuals: A systematic review of empirical barrier research. Management Review Quarterly 65: 113–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freel, Mark S. 2007. Are small innovators credit rationed? Small Business Economics 28: 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecerf, Marjorie, and Nessrine Omrani. 2019. SME Internationalization: The Impact of Information Technology and Innovation. Journal of Knowledge Economy, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Neil, Hiba Sameen, and Marc Cowling. 2015. Access to finance for innovative SMEs since the financial crisis. Research Policy 44: 370–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, William R., and Ramanda Nanda. 2015. Financing innovation. Annual Review of Financial Economics 7: 445–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kersten, Renate, Job Harms, Kellie Liket, and Karen Maas. 2017. Small Firms, large Impact? A systematic review of the SME Finance Literature. World Development 97: 330–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kędzior, Marcin. 2012. Capital structure in EU selected countries—Micro and macro determinants. Argumenta Oeconomica 28: 69–117. [Google Scholar]

- Kijkasiwat, Ploypailin, and Pongsutti Phuensane. 2020. Innovation and Firm Performance: The Moderating and Mediating Roles of Firm Size and Small and Medium Enterprise Finance. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 13: 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacevic, Tamara. 2019. EU Budget: Who Pays most in and Who Gets most back? BBC News. May 28. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-politics-48256318 (accessed on 11 November 2019).

- Kumar, Satish, and Purnima Rao. 2015. A conceptual framework for identifying financing preferences of SMEs. Small Enterprise Research 22: 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeira, Maria José, João Carvalho, Jacinta Raquel Miguel Moreira, Filipe AP Duarte, and Flávio de São Pedro Filho. 2017. Barriers to innovation and the innovative performance of Portuguese firms. Journal of Business 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Modigliani, Franco, and Merton H. Miller. 1958. The cost of capital, corporation finance and the theory of investment. The American Economic Review 48: 261–97. [Google Scholar]

- Moritz, Alexandra, Block Joern H., and Heinz Andreas. 2016. Financing patterns of European SMEs—An empirical taxonomy. An International Journal of Entrepreneurial Finance 16: 115–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, Stewart C., and Nicholas S. Majluf. 1984. Corporate financing and investment decisions when firms have information that investors do not have. Journal of Financial Economics 13: 187–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neely, Lynn, and Howard Van Auken. 2012. An examination of small firm bootstrap financing and use of debt. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship 17: 1250002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. 2013. Supporting Investment in Knowledge Capital, Growth and Innovation. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Oke, Adegoke, Gerard Burke, and Andrew Myers. 2007. Innovation types and performance in growing UK SMEs. International Journal of Operations Production Management 27: 735–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Argilés, Raquel, Macro Vivarelli, and Peter Voigt. 2009. R&D in SMEs: A paradox? Small Business Economics 33: 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oslo, Manual. 2018. Oslo Manual 2018: Guidelines for Collecting, Reporting and Using Data on Innovation. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Ou, Charles, and Geogre W. Haynes. 2006. Acquisition of Additional Equity Capital by Small Firms—Findings from the National Survey of Small Business Finances. Small Business Economics 27: 157–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadimitriou, Stratos, and Panos Mourdoukoutas. 2002. Bridging the start-up equity financing gap: Three policy models. European Business Review 14: 104–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pełka, Marcin. 2018. Analysis of innovations in the European Union via ensemble symbolic density clustering. Econometrics 22: 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SAFE. 2018. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/access-to-finance/data-surveys (accessed on 30 September 2019).

- Santarelli, Enrico, and Alessandro Sterlacchini. 1990. Innovation, formal vs. informal R&D, and firm size: Some evidence from Italian manufacturing firms. Small Business Economics 2: 223–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sau, Lino. 2007. New Pecking Order Financing for Innovative Firms: An Overview. Working Paper Series. Torino: Universita di Torino. Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/3659/ (accessed on 25 March 2020).

- Savlovschi, Ludovica Ioana, and Nicoleta Raluca Robu. 2011. The role of SMEs in modern economy. Economia, Seria Management 14: 277–81. [Google Scholar]

- Schenk, Andreas. 2015. Crowdfunding in the context of traditional financing for innovative SMEs. In European Conference on Innovation and Entrepreneurship. Reading: Academic Conferences International Limited, pp. 636–43. [Google Scholar]

- Schumpeter, Joseph A. 1942. Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy. New York: Harper. [Google Scholar]

- Schumpeter, Joseph A. 1934. The Theory of Economic Development. Cambridge: Harvard Economic Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Skuras, Dimitris, Kyriaki Tsegenidi, and Kostas Tsekouras. 2008. Product innovation and the decision to invest in fixed capital assets: Evidence from an SME survey in six European Union member states. Research Policy 37: 1778–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavassoli, Sam, and Charlie Karlsson. 2015. Persistence of various types of innovation analyzed and explained. Research Policy 44: 1887–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurik, Roy, and Sander Wennekers. 2004. Entrepreneurship, small business and economic growth. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 11: 140–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dijk, Bob, René Den Hertog, Bert Menkveld, and Roy Thurik. 1997. Some new evidence on the determinants of large-and small-firm innovation. Small Business Economics 9: 335–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaona, Andrea, and Mario Pianta. 2008. Firm size and innovation in European manufacturing. Small Business Economics 30: 283–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varis, Miika, and Hannu Littunen. 2010. Types of innovation, sources of information and performance in entrepreneurial SMEs. European Journal of Innovation Management 13: 128–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilescu, Laura. 2014. Accessing Finance for Innovative EU SMEs Key Drivers and Challenges. Economic Review Journal of Economics and Business 12: 35–47. [Google Scholar]

- Wadhwa, Anu, Corey Phelps, and Suresh Kotha. 2016. Corporate venture capital portfolios and firm innovation. Journal of Business Venturing 31: 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Chuanrong, Xiaoming Yang, Veronika Lee, and Mark E. McMurtrey. 2019. Influence of Venture Capital and Knowledge Transfer on Innovation Performance in the Big Data Environment. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 12: 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittam, Geoff Paul Stuart, and Janette Wyper. 2007. The pecking order hypothesis: Does it apply to start-up firms? Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 14: 8–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, James A., and Timothy L. Pett. 2006. Small-firm performance: Modeling the role of product and process improvements. Journal of Small Business Management 44: 268–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Clusters 1st Demarcation | Sub-Clusters 2nd Demarcation | Countries | Reasoning |

|---|---|---|---|

| OLD_EU | INNER_C (inner core) | Belgium France Germany Italy Luxembourg The Netherlands UK | Founders of the EU and UK as the largest net contributor |

| OUTER_C (outer core) | Austria Denmark Finland Greece Ireland Portugal Spain Sweden | The remainder ‘old’ EU member states | |

| NEW_EU | INNER_P (inner peripheral) | Cyprus Estonia Latvia Lithuania Malta Slovakia Slovenia | ‘New’ EU member states (since 2004 or later), in the Eurozone |

| OUTER_P (outer peripheral) | Bulgaria Croatia Czech Republic Hungary Poland Romania | ‘New’ EU member states (since 2004 or later), outside the Eurozone |

| Variable | Definition |

|---|---|

| Types of SMEs innovation | |

| Product | The percentage of companies which declared that they introduced significant improvements in products or services within the past year. |

| Process | The percentage of companies which declared that they introduced significant improvements of production process or methods within the past year. |

| Management | The percentage of companies which declared that they introduced a new organization of management within the past year. |

| Sales | The percentage of companies which declared that they introduced a new way of selling goods or services. |

| Relevance of SMEs financing | |

| INTERNAL FINANCING | The percentage of surveyed companies which declared the relevance of internal sources of financing (retained earnings and sales of assets were used over the past 6 months or are considered to be used in the future). |

| EXTERNAL EQUITY | The percentage of surveyed companies which declared the relevance of external sources of equity (equity capital was used over the past 6 months or is considered to be used in the future). |

| DEBT | The percentage of surveyed companies which declared the relevance of debt (debt was used over the past 6 months or is considered to be used in the future). |

| Data | Type of Innovations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product | Process | Manag. | Sales | ||

| Clusters—1st demarcation (old/new EU) | |||||

| p-value U Mann–Whitney test | 0.000 ** | 0.332 | 0.000 ** | 0.038 ** | |

| Sub-clusters—2nd demarcation (IC/OC/IP/OP) | |||||

| p-value H Kruskal–Wallis test | 0.000 ** | 0.186 | 0.000 ** | 0.002 ** | |

| Post-hoc tests pairwise comparisons | IC/IP | 0.000 ** | 0.012 ** | 1.000 | |

| IC/OP | 0.000 ** | 0.001 ** | 1.000 | ||

| IC/OC | 0.004 ** | 1.000 | 0.610 | ||

| OC/IP | 0.182 | 0.001 ** | 0.475 | ||

| OC/OP | 1.000 | 0.000 ** | 0.001 ** | ||

| OP/IP | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.318 | ||

| Declared Types of Innovations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product | Process | Management | Sales | |

| Old EU | ||||

| Product | 1 | |||

| Process | 0.676 ** | 1 | ||

| Management | 0.077 | 0.282 * | 1 | |

| Sales | 0.653 ** | 0.714 ** | 0.356 ** | 1 |

| New EU | ||||

| Product | 1 | |||

| Process | 0.675 ** | 1 | ||

| Management | 0.460 ** | 0.529 ** | 1 | |

| Sales | 0.464 ** | 0.455 ** | 0.744 ** | 1 |

| Inner Core | ||||

| Product | 1 | |||

| Process | 0.432 ** | 1 | ||

| Management | 0.206 | 0.744 ** | 1 | |

| Sales | 0.395 * | 0.648 ** | 0.425 * | 1 |

| Outer Core | ||||

| Product | 1 | |||

| Process | 0.839 ** | 1 | ||

| Management | −0.033 | −0.011 | 1 | |

| Sales | 0.667 ** | 0.773 ** | 0.351 * | 1 |

| Inner Peripheral | ||||

| Product | 1 | |||

| Process | 0.616 ** | 1 | ||

| Management | 0.363 * | 0.323 | 1 | |

| Sales | 0.310 | 0.100 | 0.628 ** | 1 |

| Outer Peripheral | ||||

| Product | 1 | |||

| Process | 0.761 ** | 1 | ||

| Management | 0.579 ** | 0.849 ** | 1 | |

| Sales | 0.609 ** | 0.821 ** | 0.887 ** | 1 |

| Product | Process | Management | Sales | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Old EU | ||||

| Internal | 0.252 * | 0.112 | −0.277 * | 0.019 |

| External Equity | 0.042 | −0.072 | −0.220 | −0.055 |

| Debt | 0.200 | 0.451 ** | 0.328 ** | 0.464 ** |

| New EU | ||||

| Internal | 0.194 | 0.255 * | 0.216 | 0.184 |

| External Equity | 0.218 | 0.482 ** | 0.261 * | 0.241 |

| Debt | 0.396 ** | 0.431 ** | 0.458 ** | 0.363 ** |

| Inner Core | ||||

| Internal | 0.321 | 0.220 | 0.185 | 0.139 |

| External Equity | −0.148 | −0.016 | −0.080 | 0.081 |

| Debt | −0.145 | 0.364 * | 0.373 * | 0.290 |

| Outer Core | ||||

| Internal | 0.205 | 0.046 | −0.591 ** | 0.205 |

| External Equity | −0.023 | −0.120 | −0.314 * | −0.023 |

| Debt | 0.462 ** | 0.511 ** | 0.304 | 0.462 ** |

| Inner Peripheral | ||||

| Internal | 0.257 | 0.156 | 0.097 | 0.238 |

| External Equity | 0.150 | 0.366 * | 0.078 | 0.027 |

| Debt | 0.331 | 0.326 | 0.551 ** | 0.526 ** |

| Outer Peripheral | ||||

| Internal | 0.057 | 0.338 | 0.339 | 0.100 |

| External Equity | 0.219 | 0.573 ** | 0.534 ** | 0.417 * |

| Debt | 0.465 ** | 0.518 ** | 0.212 | 0.152 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Błach, J.; Wieczorek-Kosmala, M.; Trzęsiok, J. Innovation in SMEs and Financing Mix. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2020, 13, 206. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm13090206

Błach J, Wieczorek-Kosmala M, Trzęsiok J. Innovation in SMEs and Financing Mix. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2020; 13(9):206. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm13090206

Chicago/Turabian StyleBłach, Joanna, Monika Wieczorek-Kosmala, and Joanna Trzęsiok. 2020. "Innovation in SMEs and Financing Mix" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 13, no. 9: 206. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm13090206

APA StyleBłach, J., Wieczorek-Kosmala, M., & Trzęsiok, J. (2020). Innovation in SMEs and Financing Mix. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 13(9), 206. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm13090206