The Impact of Brand Relationships on Corporate Brand Identity and Reputation—An Integrative Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

- -

- helps fill a gap in the literature by supplying a concept of brand relationships

- -

- introduces the concept of brand relationships in the management of brand identity and reputation in higher education;

- -

- relates the concept of corporate brand reputation with the management of corporate brand identity;

- -

- leads brand managers into new perspectives for building a new dynamic construct under a brand relationship approach.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Brand Relationships

2.2. Corporate Brand Identity

2.3. Brand Reputation

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Stages

- Exploratory research used a case study methodology developed in two engineering faculties to find items to characterize the dimensions proposed in the model; and

- Confirmatory research was pursued by developing a questionnaire for higher education engineering students. A total of 216 complete surveys were obtained.

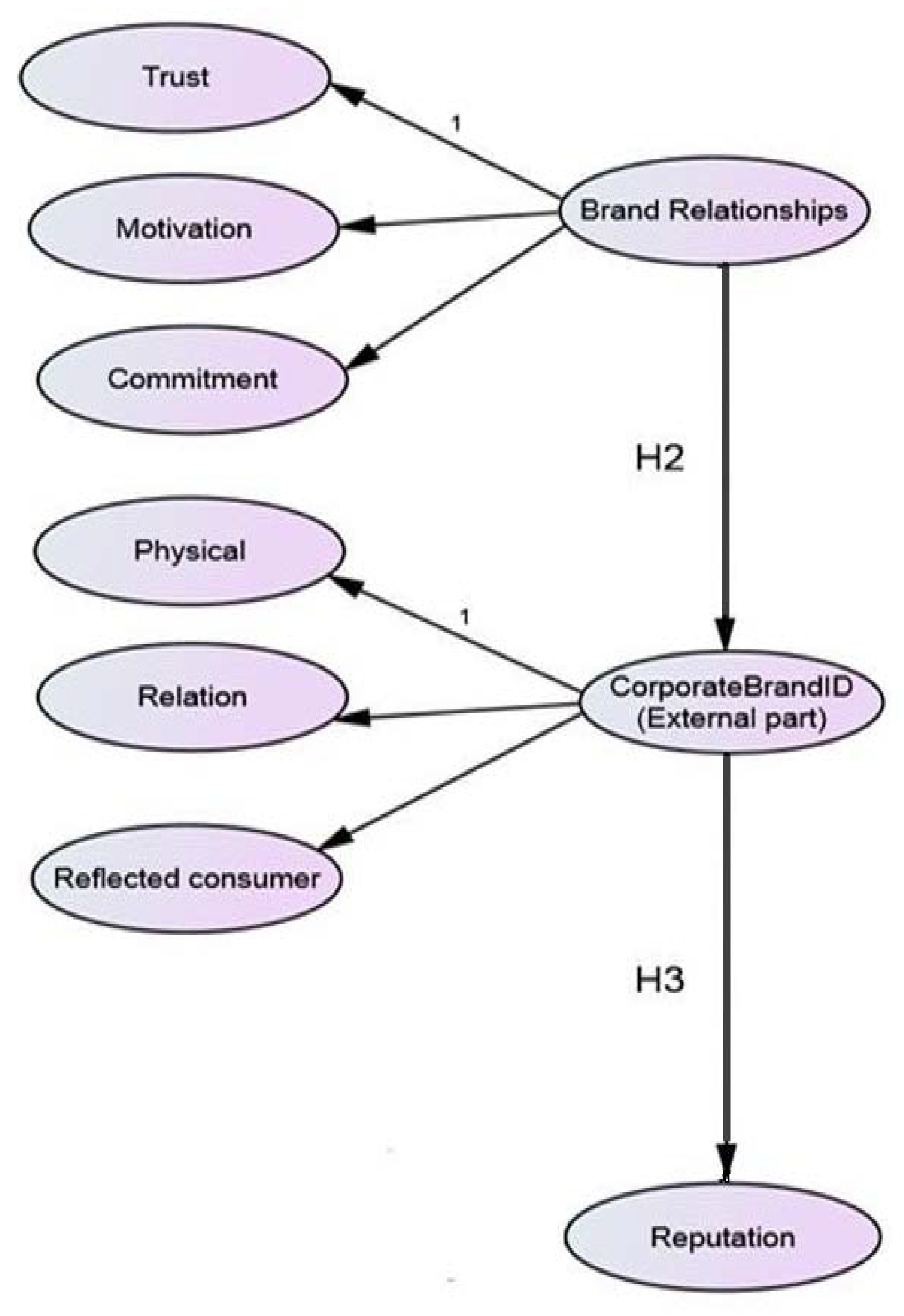

3.2. Proposed Model and Testing

3.3. Research Hypotheses

- (a)

- A list of eighteen items was obtained from qualitative research to measure the constructs that define the brand relationships concept: trust (7 items), motivation (7 items), and commitment (four items);

- (b)

- Eight items were considered before testing the validity of the measurement model. The guidelines followed by the literature regarding SEM suggested a drop of T4. In line with this, the trust dimension was characterized by seven items;

- (c)

- A list of thirteen items was derived from previous research by Barros et al. (2016), regarding corporate brand identity (external part) and its measures: physical (four items); relation (five items); reflected consumer (four items);

- (d)

- A list of four items was adapted from the brand reputation scale developed by Vidaver-Cohen (2007). Previously, ten items had been selected from the framework, but we found that this concept was bidimensional, so, we selected one dimension that we considered to be more connected with this research. After analyzing the measurement model, we decided to maintain three of the four items.

4. Results

4.1. Unidimensionality and Reliability of Scales for Measuring Brand Relationships, Reputation and Corporate Identity

4.1.1. Trust

4.1.2. Commitment

4.1.3. Motivation

4.2. Guidelines and Criteria to Assess Model for Brand Relationships

- -

- CMIN/DF < 2.00 (Byrne 1989, 2010);

- -

- -

- RMSEA < 0.08 (Bentler 1990; Browne and Cudeck 1993; Hair et al. 2006; Hu and Bentler 1999; Marsh et al. 1996).where CMIN/DF = Chi-square value/degrees of freedom, CFI = comparative fit index, RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation.

4.3. Model Evaluation

4.4. Final Structural Model Estimation and Testing

5. Discussion and Conclusions

6. Limitations of the Research, Future Directions and Contributions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aaker, David Allen. 2004. Leveraging the Corporate Brand. California Management Review 46: 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, Pankaj. 2004. The Effects of Brand Relationship Norms on Consumer Attitudes and Behavior. Journal of Consumer Research 31: 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhawaldeh, Abdelbaset, Abdallah Alsaad, Abdallah Taamneh, and Hussein Alhawamdeh. 2020. Examining Antecedents and Consequences of University Brand Image. Management Science Letters 10: 953–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argenti, Paul, and Bob Druckenmiller. 2004. Reputation and the Corporate Brand. Corporate Reputation Review 7: 368–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, Richard, Youjae Yi, and Lynn Philips. 1991. Assessing Construct Validity in Organizational Research. Administrative Science Quarterly 36: 421–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balmer, John M. T. 2001. From the Pentagon: A new identity framework. Corporate Reputation Review 4: 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balmer, John, and Edmund Gray. 2003. Corporate Brands: What Are They? What of Them? European Journal of Marketing 37: 972–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balmer, John, and Mei-Na Liao. 2007. Student Corporate Brand Identification: An Exploratory Case Study. Corporate Communications: An International Journal 12: 356–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balmer, John, Mei-Na Liao, and Wei-Yue Wang. 2010. Corporate Brand Identification and Corporate Brand Management: How Top Business Schools Do It. Journal of General Management 35: 77–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, Teresa, Francisco Vitorino Martins, and Hortênsia Gouveia Barandas. 2011. Corporate Brand Identity Management—Proposal of a New Framework. In 7th International Conference of: The AM’s Brand and Corporate Reputation SIG. Oxford: Academy of Marketing. [Google Scholar]

- Barros, Teresa, Francisco Vitorino Martins, and Hortênsia Gouveia Barandas. 2016. Corporate Brand Identity Measurement—An Application to the Services Sector. International Journal of Innovation and Learning 20: 214–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, Rajeev, and Richard Bagozzi. 2012. Brand Love. Journal of Marketing 76: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beatty, Sharon, Pamela Homer, and Lynn Kahle. 1988. The Involvement—Commitment Model: Theory and Implications. Journal of Business Research 16: 149–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, Peter. 1990. Comparative Fit Indexes in Structural Models. Psychological Bulletin 107: 238–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, Leonard. 1995. Relationship Marketing of Service: Growing Interest, Emerging Perspectives. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 23: 236–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bland, J. Martin, and Douglas Altman. 1997. Statistics Notes: Cronbach’s Alpha. British Management Journal 314: 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, Michael, and Robert Cudeck. 1993. Alternative Ways of Assessing Model Fit. Sage Focus Editions 154: 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burmann, Christoph, Marc Jost-Benz, and Nicola Riley. 2009. Towards an Identity-based Brand Equity Model. Journal of Business Research 62: 390–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, Barbara. 1989. A Primer of LISREL: Basic Applications and Programming for Confirmatory Factor Analytic Models. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, Barbara. 2010. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri, Arjun, and Morris Holbrook. 2001. The Chain of Effects from Brand Trust and Brand Affect to Brand Performance: The Role of Brand Loyalty. Journal of Marketing 65: 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, Gilbert. 1979. A Paradigm for Developing Better Measures of Marketing Constructs. Journal of Marketing Research 16: 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silveira, Catherine, Carmen Lages, and Cláudia Simões. 2013. Reconceptualizing Brand Identity in a Dynamic Environment. Journal of Business Research 66: 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Chernatony, Leslie. 1999. Brand Management through Narrowing the Gap between Brand Identity and Brand Reputation. Journal of Marketing Management 15: 157–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Chernatony, Leslie, and Fiona Harris. 2000. Developing Corporate Brands through Considering Internal and External Stakeholders. Corporate Reputation Review 3: 268–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekovic, Maja, Jan M. Janssens, and Jan R. Gerris. 1991. Factor Structure and Construct Validity of the Block Child Rearing Practices Report (CRPR). Psychological Assessment: A Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 3: 182–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, Rohit, Farley John, and Webster Frederick, Jr. 1993. Corporate Culture, Customer Orientation, and Innovativeness in Japanese Firms: A Quadrad Analysis. Journal of Marketing 57: 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVellis, Robert. 2003. Scale Development: Theory and Applications. Chapel Hill: Sage, University of North Carolina. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer, Robert, Paul Schurr, and Sejo Oh. 1987. Developing Buyer-Seller Relationships. Journal of Marketing 51: 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, Jeffrey, and Richard Bagozzi. 2000. On the Nature and Direction of the Relationship between Constructs and Measures. Psychological Methods 5: 155–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fombrum, Charles. 1996. Reputation: Realizing Value from the Corporate Image. Boston: Harvard Business School Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fombrum, Charles. 2006. The Rep Track System. Paper presented at the 10th Anniversary Conference on Reputation, Image, Identity and Competitiveness, New York, NY, USA, May 25–28. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, David, Lars-Erik Gadde, Hakan Hakansson, and Ivan Snehota. 2003. Managing Business Relationships. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Fournier, Susan. 1998. Consumers and Their Brands: Developing Relationship Theory in Consumer Research. Journal of Consumer Research 24: 343–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbarino, Ellen, and Mark S. Johnson. 1999. The Different Roles of Satisfaction, Trust, and Commitment in Customer Relationships. Journal of Marketing 63: 70–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurviez, Patricia, and Michael Korchia. 2002. Proposition d’Une Échelle de Mesure Multidimensionnelle de la Confiance dans la Marque. Recherche et Applications en Marketing 17: 41–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joseph, William Black, Barry Babin, Rolph Anderson, and Ronald Tatham. 2006. Multivariate Data Analysis. Upper Saddle River: Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Hakansson, Hakan, and David Ford. 2002. How should Companies Interact in Business Networks? Journal of Business Research 55: 133–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakansson, Hakan, and Ivan Snehota. 1989. No Business is an Island: The Network Concept of Business Strategy. Scandinavian Journal of Management 5: 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakansson, Hakan, and Ivan Snehota, eds. 1995. Developing Relationships in Business Networks. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Min, Jiacong Wu, Yu Wang, and Mingying Hong. 2018. A Model and Empirical Study on the User’s Continuance Intention in Online China Brand Communities Based on Customer-Perceived Benefits. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 4: 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardwick, Bob, and David Ford. 1986. Industrial Buyer Resources and Responsibilities and the Buyer–Seller Relationships. Industrial Marketing and Purchasing 1: 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Hatch, Mary Jo, and Majken Schultz. 2010. Brand Management Vol. 17, 8, 590–604. 1350-23IX. New York: Macmillan Publishers Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Helm, Sabrina. 2007. The Role of Corporate Reputation in Determining Investor Satisfaction and Loyalty. Corporate Reputation Review 10: 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, Ronald, Cynthia Fekken, and Dorothy Cotton. 1991. Assessing Psychopathology Using Structured Test-Item Response Latencies. Psychological Assessment 3: 111–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Li-Tze, and Peter M. Bentler. 1999. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling 6: 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, Lawrence R., Stanley A. Mulaik, and Jeanne M. Brett. 1982. Causal Analysis: Assumptions, Models and Data. Beverly Hills: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Jöreskog, Karl, and Dag Sörbom. 2001. LISREL 8: User’s Reference Guide, 2nd ed. Chicago: Scientific Software International. [Google Scholar]

- Kapferer, Jean-Noel. 1986. Beyond Positioning, Retailer’s Identity. Brussels: Esomar Seminar Proceedings, pp. 167–76. [Google Scholar]

- Kapferer, Jean-Noel. 2008. The New Strategic Brand Management—Creating and Sustaining Brand Equity Long Term, 4th ed. London: Kogan Page Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, Kevin Lane. 2003. Brand Synthesis: The Multidimensionality of Brand Knowledge. Journal of Consumer Research 29: 595–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, Kevin Lane, and Donald R. Lehmann. 2006. Brands and Branding: Research Findings and Future Priorities. Marketing Science 25: 740–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, Mary Susan, Linda Ferrel, and Debbie Thorne LeClair. 2000. Consumers’ Trust of Salesperson and Manufacturer: An Empirical Study. Journal of Business Research 51: 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, Stephen. 1991. Brand building in the 1990s. Journal of Marketing Management 7: 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, Yvonna S, and Egon G. Guba. 1985. Naturalistic Inquiry. Newbury Park: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Madden, Thomasrank J., Frank Fehle, and Susan Fournier. 2006. Brands Matter: An Empirical Demonstration of the Creation of Shareholder Value through Branding. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 34: 224–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, Naresh K. 1981. A Scale to Measure Self-concepts, Person Concepts, and Product Concepts. Journal of Marketing Research 18: 456–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, Naresh K. 2004. Marketing Research, 4th ed. Upper Saddle River: Pearson-Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Marôco, João. 2010. Análise de Equações Estruturais, Fundamentos Teóricos, Software & Aplicações. Pêro Pinheiro: ReportNumber, Lda. ISBN 9789899676336. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, Herbert, John Balla, and Kit-Tai Hau. 1996. An Evaluation of Incremental Fit Indices: A Clarification of Mathematical and Empirical Properties. In Advanced Structural Equation Modeling: Issues and Techniques. Edited by George A. Marcoulides and Randall E. Schumacker. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, pp. 315–53. [Google Scholar]

- Moorman, Christine, Gerald Zaltman, and Rohit Deshpande. 1992. Relationships between Providers and Users of Market Research: The Dynamics of Trust. Journal of Marketing Research 29: 314–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, Robert M., and Shelby D. Hunt. 1994. The Commitment–Trust Theory of Relationship Marketing. Journal of Marketing 58: 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muniz, Albert Muñiz, Jr., and Thomas C. O’Guinn. 2001. Brand Community. Journal of Consumer Research 27: 412–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachtigall, Christof, Rolf Steyer, and Wuthich-Martone. 2001. Causal Effects in Empirical Research. In Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Causality: Bern Studies in the History and Philosophy of Science. Edited by Michael May and Uwe Ostermeier. Norderstedt: Libri Books, pp. S1–S100. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, Jum. 1978. Psychometric Theory, 2nd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, Jum, and Ira Bernstein. 1994. Psychometric Theory. New York: McGraw-Hill Higher. [Google Scholar]

- Payne, Adrian, Kaj Storbacka, Pennie Frow, and Simon Knox. 2009. Co-creating Brands: Diagnosing and Designing the Relationship Experience. Journal of Business Research 62: 379–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ping, Robert A. 2004. On Assuring Valid Measures for Theoretical Models Using Survey Data. Journal of Business Research 57: 125–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, Coimbatore Krishnarao, and Venkat Ramaswamy. 2004. Co-creation Experiences: The Next Practice in Value Creation. Journal of Interactive Marketing 18: 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priporas, Constantinos Vasilios, and Irene Kamenidou. 2011. Perceptions of Potential Postgraduate Greek Business Students towards UK Universities Brand and Brand Reputation. Journal of Brand Management 18: 264–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Akshay R., Lu Qu, and Robert W. Rueker. 1999. Signaling Unobservable Product Quality through a Brand Ally. Journal of Marketing Research 36: 258–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauyruen, Papassapa, and Keneth E. Miller. 2007. Relationship Quality as a Predictor of B2B Customer Loyalty. Journal of Business Research 60: 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonin, Bernard, and Julie Ruth. 1998. Is a Company Known by the Company It Keeps? Assessing the Spillover Effects of Brand Alliances on Consumer Brand Attitudes. Journal of Marketing Research 35: 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirieix, Lucien, and Pierre-Louis Dubois. 1999. Vers un Modèle Qualité-satisfaction Intégrant la Confiance? Recherche et Applications en Marketing 14: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Søderberg, Anne-Marie, Sundar Krishna, and Pernille Bjørn. 2013. Global Software Development: Commitment, Trust and Cultural Sensitivity in Strategic Partnerships. Journal of International Management 19: 347–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suomi, Kati. 2014. Exploring the Dimensions of Brand Reputation in Higher Education—A Case Study of a Finnish Master’s Degree Programme. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management 36: 646–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Lans, Ralf, Bram van den Bergh, and Evelien Dieleman. 2014. Partner Selection in Brand Alliances: An Empirical Investigation of the Drivers of Brand Fit. Marketing Science 33: 551–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidaver-Cohen, Deborah. 2007. Reputation beyond the Rankings: A Conceptual Framework for Business School Research. Corporate Reputation Review 10: 278–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, David T. 1995. An Integrated Model of Buyer–Seller Relationships. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 23: 335–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Procedure to Develop Multi-Item Scales | Techniques and Indicators |

|---|---|

| 1—Develop a theory | Literature review and discussion with experts |

| 2—Generate an initial pool of items for each dimension/scale | Theory, secondary data, and thirteen interviews with lecturers and university managers, four focus groups of students (bachelor, master, and doctoral) |

| 3—Select a reduced set of items based on qualitative judgment | Panel of ten experts (national and international, academics, and practitioners) |

| 4—Collect data from a large pretest sample | Pretest on a sample of eighty higher education Students |

| 5—Perform statistical analysis | Reliability; factor analysis |

| 6—Purify the measures | Analysis of the results of the pretest sample and discussion with experts |

| 7—Collect data | Survey of higher education students (216 complete surveys) |

| 8—Assess reliability and unidimensionality | Cronbach’s alpha and factor analysis |

| 9—Assess validity | Construct (AVE and CR), discriminant (comparison between the squared root of AVE and the simple correlations), and nomological validity (significant simple correlations examination) |

| 10—Perform statistical analysis | Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) Structural equation modelling (SEM) |

| Construct | Initial Full Measured Items * | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Trust | The connections between my university/institution and the recognized brands (INESC, INEGI, ISISE, CCT, CALG, ALGORITMI; MIT, Harvard, Oxford…) with whom it relates T1—make me feel safe T2—are trustable T3—are a guarantee T4—are transparent (honest)—deleted while testing the measurement model of brand relationships for the sake of discriminant validity between trust and commitment T5—are sincere T6—are interesting T7—influence the curricula offer of my university/institution T8—contribute to improving the answers to students’ needs | Adapted from Morgan and Hunt (1994) and Gurviez and Korchia (2002) |

| Commitment | Attending this university/institution allows me C1—to achieve (have access to) important relationship networks C2—to be able to play a major professional and social role C3—to be influential C4—to reach technical and scientific excellence | Concept based on Hardwick and Ford (1986) and Wilson (1995), but the scales are new in the literature; Sources of influence: informants + focus groups + experts + desk research |

| Motivation | The connections between my university/institution and the recognized brands (INESC, INEGI, ISISE, CCT, CALG, ALGORITMI; MIT, Harvard, Oxford…) with whom it relates M1—give credibility to the lecturing process M2—facilitate access to research M3—facilitate access to the labor market M4—facilitate access to a top career M5—give credibility to the university/institution in the eyes of the labor market M6—facilitate access to an international career M7—foster entrepreneurship | New scale in literature; sources of influence: informants + focus groups + experts + desk research |

| Reflected consumer | I believe that society in general considers graduates of my university/institution RC1—better prepared for the labor market RC2—more capable of creating/innovating RC3—successful professionals RC4—professionals with high credibility | Developed in previous research |

| Relation | I feel that the relationship between my university/institution and me is R1—friendly R2—respectful R3—trustable R4—motherly R5—close | Developed in previous research |

| Physical | F1—the facilities of my university/institution are modern F2—the facilities of my university/institution are sophisticated F3—the facilities of my university/institution are functional F4—the facilities of my university/institution are adequate | Developed in previous research |

| Reputation | Please classify the items below from 1—poor to 5—high: Rep2.1—intellectual performance (retain/recruit prestigious lecturers/investigators; high levels of scientific publications…) Rep2.2—network performance (attracts first-class students; high employment rate; strong links between students and the industry…) Rep2.3—products (prestigious degrees; competent graduates…) Rep2.4—innovation (innovative methodologies; rapid adaptation to changes; innovating curricula…) deleted after analyzing the measurement model (standardized residual values) Rep2.5—provided services (strong relations with the exterior; specialized tasks; high level of instruction by lecturers and staff…) Rep2.6—leadership (strong and charismatic leaders; organized and competent management; vision for future…) Rep2.7—corporate governance (open and transparent management; ethical behavior; fair in transactions with stakeholders…) Rep2.8—work environment (equal opportunities; reward systems; care for the welfare of the staff and students…) Rep2.9—citizenship (promotes services to society; supports good causes; acts positively in society; open to the industry and to society…) Rep2.10—financial performance (fees and value-added programs.) From Rep2.5 to Rep2.10 all deleted after analyzing the dimensionality of the construct, because SEM demands unidimentionality of the scales as previously mentioned—see Table 3 | Adapted from Vidaver-Cohen (2007) |

| Reputation | Factor Loadings | |

|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | |

| Rep2.1—intellectual performance (retain/recruit prestigious lecturers/investigators; high levels of scientific publications…) | 0.800 | |

| Rep2.2—network performance (attracts first-class students; high employment rate; strong links between the students and industry…) | 0.813 | |

| Rep2.3—products (prestigious degrees; competent graduates…) | 0.736 | |

| Rep2.4—innovation (innovative methodologies; rapid adaptation to changes; innovative curricula…) | 0.685 | |

| Rep2.5—provided services (strong relations with the exterior; specialized tasks; high level of instruction by lecturers and staff…) | 0.591 | 0.449 |

| Rep2.6—leadership (strong and charismatic leaders; organized and competent management; vision for future…) | 0.616 | |

| Rep2.7—corporate governance (open and transparent management; ethical behavior; fair in transactions with stakeholders…) | 0.822 | |

| Rep2.8—work environment (equal opportunities; reward systems; care for welfare of staff and students…) | 0.821 | |

| Rep2.9—citizenship (promotes services to society; supports good causes; acts positively in society; open to the industry and to society…) | 0.709 | |

| Extraction Method: Principal Component Analysis | ||

| Measured Items | Factor Loadings λ | ∑a | Delta b | AVE | CR | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trust (T) | 0.53 | 0.89 | 0.885 | |||

| T1 | 0.713 | 0.492 | ||||

| T2 | 0.816 | 0.334 | ||||

| T3 | 0.713 | 0.492 | ||||

| T5 | 0.657 | 0.568 | ||||

| T6 | 0.733 | 0.463 | ||||

| T7 | 0.759 | 0.424 | ||||

| T8 | 0.683 | 5.074 | 0.534 | |||

| Commitment (C) | 0.77 | 0.82 | 0.819 | |||

| C1 | 0.705 | 0.308 | ||||

| C2 | 0.716 | 0.487 | ||||

| C3 | 0.653 | 0.574 | ||||

| C4 | 0.717 | 2.791 | 0.316 | |||

| Motivation (M) | 0.52 | 0.89 | 0.886 | |||

| M1 | 0.647 | 0.581 | ||||

| M2 | 0.723 | 0.477 | ||||

| M3 | 0.696 | 0.516 | ||||

| M4 | 0.761 | 0.421 | ||||

| M5 | 0.735 | 0.460 | ||||

| M6 | 0.771 | 0.406 | ||||

| M7 | 0.731 | 5.064 | 0.466 |

| Construct validity (before drop T4) | |||

| Motivation | Trust | Commitment | |

| AVE | 0.52 | 0.51 | 0.77 |

| CR | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.82 |

| Discriminant validity (before drop T4) | |||

| Motivation | 0.72 | ||

| Trust | 0.67 | 0.72 | |

| Commitment | 0.65 | 0.73 | 0.88 |

| Construct validity (after drop T4) | |||

| Motivation | Trust | Commitment | |

| AVE | 0.52 | 0.53 | 0.77 |

| CR | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.82 |

| Discriminant validity (after drop T4) | |||

| Motivation | 0.72 | ||

| Trust | 0.67 | 0.73 | |

| Commitment | 0.65 | 0.72 | 0.88 |

| Model | χ2 | DF | p | CMIN/DF | CFI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brand relationships (three factors) | 219.023 | 129 | 0.000 | 1.698 | 0.955 | 0.057 [0.044; 0.070] |

| Model | χ2 | DF | p | CMIN/DF | CFI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement model (Brand relationships; corporate brand identity (external) and reputation) | 726.149 | 503 | 0.000 | 1.444 | 0.944 | 0.045 [0.038; 0.053] |

| Model | χ2 | DF | p | CMIN/DF | CFI | RMSEA | PCFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structural model (Brand relationships; corporate brand identity (external) and reputation) | 727.239 | 504 | 0.000 | 1.443 | 0.944 | 0.045 [0.038; 0.053] | 0.847 |

| Relationships between the Constructs | Regression Estimates | Statistics | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unstandardized | S.E. | Standardized | C.R. | p-Value | Decision | |||

| External Corporate Brand ID | <--- | Brand relationships | 0.652 | 0.135 | 0.876 | 4.830 | <0.001 | H2 supported |

| Physical | <--- | External Corporate Brand ID | 1.000 | 0.421 | ||||

| Relation | <--- | External Corporate Brand ID | 1.419 | 0.302 | 0.762 | 4.695 | <0.001 | |

| Reflected consumer | <--- | External Corporate Brand ID | 1.185 | 0.242 | 0.797 | 4.890 | <0.001 | |

| Trust | <--- | Brand relationships | 1.000 | 0.801 | ||||

| Motivation | <--- | Brand relationships | 0.625 | 0.093 | 0.771 | 6.698 | <0.001 | |

| Commitment | <--- | Brand relationships | 1.031 | 0.144 | 0.937 | 7.156 | <0.001 | |

| Reputation | <--- | External Corporate Brand ID | 1.302 | 0.260 | 0.824 | 5.012 | <0.001 | H3 supported |

| Endogenous Construct | R2 |

|---|---|

| External Corporate Brand ID | 0.768 |

| Physical | 0.177 |

| Relation | 0.581 |

| Reflected consumer | 0.636 |

| Trust | 0.641 |

| Motivation | 0.595 |

| Commitment | 0.878 |

| Reputation | 0.680 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barros, T.; Rodrigues, P.; Duarte, N.; Shao, X.-F.; Martins, F.V.; Barandas-Karl, H.; Yue, X.-G. The Impact of Brand Relationships on Corporate Brand Identity and Reputation—An Integrative Model. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2020, 13, 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm13060133

Barros T, Rodrigues P, Duarte N, Shao X-F, Martins FV, Barandas-Karl H, Yue X-G. The Impact of Brand Relationships on Corporate Brand Identity and Reputation—An Integrative Model. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2020; 13(6):133. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm13060133

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarros, Teresa, Paula Rodrigues, Nelson Duarte, Xue-Feng Shao, F. V. Martins, H. Barandas-Karl, and Xiao-Guang Yue. 2020. "The Impact of Brand Relationships on Corporate Brand Identity and Reputation—An Integrative Model" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 13, no. 6: 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm13060133

APA StyleBarros, T., Rodrigues, P., Duarte, N., Shao, X.-F., Martins, F. V., Barandas-Karl, H., & Yue, X.-G. (2020). The Impact of Brand Relationships on Corporate Brand Identity and Reputation—An Integrative Model. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 13(6), 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm13060133