1. Introduction

During the previous three decades, there was a revolutionary shift in the understanding of the purpose of business and its role in contemporary societies. Compared to the traditional narrow focus on “making profit”, emphasised since the early 1970s when Milton Friedman declared it the core of entrepreneurial activity, a more comprehensive notion emerged, integrating economic activity with the promotion of social values and sustainability. As a result, societal and environmental concerns have been integrated both into the business operations of many companies as well as their risk management (

Hanggraeni et al. 2019;

Belás et al. 2015). At the same time, a variety of tools emerged to assist and promote the companies in their efforts.

The official launch of the United Nations Global Compact (UNGC) in 2000, a multi-stakeholder corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiative under the umbrella of the United Nations, and the auspices of the then Secretary-General Kofi Annan, entirely fits into this revolutionary context (cf.

Williams 2018). Its Ten Principles of human and labour rights, environmental protection and anti-corruption were designed to guide businesses in developing local action for coping with the global challenges of our time, introducing precautionary approaches to a broad range of societal and environmental issues, and preventing severe failures, such as child labour or corruption.

In the following two decades, the UNGC has grown from an initial group of 44 large multinationals (

Brown et al. 2018) into the world’s largest CSR initiative, often being considered the most prominent one (

Abdelzaher et al. 2019). Currently, it reports on over 12,000 participants (of which approximately 9500 are companies) from more than 160 countries (

UNGC 2018).

However, despite the prominent position of the UNGC within the contemporary global governance architecture, there are serious doubts about its actual impacts in the contemporary scholarly literature (cf.

Ali and Frynas 2018;

Schembera 2018;

Lim 2017;

Coulmont et al. 2017;

Zilic et al. 2019). The criticism points especially to the lack of intergovernmental legitimacy, the absence of oversight by the UN General Assembly and the blue-wash phenomenon, i.e., participation to acquire public legitimacy without any real intention to adhere to the Ten Principles of the UN Global Compact. Additionally, the gap is addressed between the “say” and “do” steps in internal policies of subscribing companies, weak accountability mechanisms, the ongoing exclusion of several groups of stakeholders as well as slow progress on the integration of Ten Principles to business operations overall (

Fortín and Jolly 2015;

Pingeot 2015). Last but not least, the problem of inconsistent participation has been discussed, but there is little empirical evidence.

This paper examines the impacts of the UNGC’s attempts to promote Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) through their integration into the regular Communications on Progress (COPs). Its purpose is to reveal the contribution of COPs to the implementation of SDGs, and to overcome divergences between societal needs and business preferences. The study is focused on the V4 region, i.e., the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia, as an example of post-transformation areas facing many challenges in terms of responsible and sustainable business conduct. The countries have been considered laggards in CSR and business ethics, due to the delay in spread of the related concepts caused by the Cold War (

Steurer and Konrad 2009), and also discrepancies in the commitment of international companies operating on their territories as well as purely domestic firms (

Fekete 2005;

Bohatá 2005;

Lenssen et al. 2006). This creates favourable conditions for research to capture the effects of various international CSR and sustainability projects as well as the constraints on their proper implementation. Moreover, it promises to provide many incentives for further studies, as there are many similarities between the V4 and other countries of Central and Eastern Europe (

Steurer and Konrad 2009).

To fulfil its aim, the paper employs qualitative content analysis of 40 Communications of Progress (COPs) and the related self-assessments in the UNGC Participation Database, submitted by 25 companies from the V4 in 2017–2019. The remainder is organised as follows:

Section 2 provides a more detailed literature review and specifies the rationale of the study.

Section 3 starts with a brief overview of the V4’s involvement in the UNGC and then provides the background for the analysis and explains our methodological approach.

Section 4 explores the coverage of SDGs by the COPs submitted to the UNGC from the “active” and “advanced” companies (i.e., business entities with over 250 full-time employees) domiciled in the V4.

Section 5 and

Section 6 summarise key findings, in particular the reluctant approach in the region to the UNGC project and its SDGs dimension, and discuss the constraints of research concentrated on a small group of companies.

2. Literature Review and the Rationale of the Study

Nevertheless, regarding the UNGC, the research so far has identified many problems, in particular, substantial cross-country differences in adoption and disclosure levels (

Ali and Frynas 2018;

Schembera 2018;

Lim 2017); insufficient quality of annual Communications on Progress (COPs), the primary tool for monitoring participants’ commitment to the UNGC Ten Principles (

Coulmont et al. 2017;

Zilic et al. 2019); as well as numerous cases of companies adhering to the Principles for the instrumental reasons of seeking protection from criticism and improving their reputation rather than having real intentions of applying them in their everyday operations (

Amer 2018;

Wettstein et al. 2019). Moreover, studies on the practical impacts of the UNGC on the business operations and risk management of companies are almost non-existent (cf.

Fortín and Jolly 2015;

Shoji 2015).

As there has been a clear connection between the UNGC Ten Principles and SDGs since their adoption (cf.

UNGC 2014), boosting the engagement of business and driving its action towards SDGs seemed a logical step. Thus, SDGs have been incorporated as an integral part of the UNGC multi-year strategy, with the aim to raising awareness, attracting companies to join and embedding SDGs into their operations. Since 2016, guidance by the UNGC has been completed with monitoring the relation of the activities described in the COPs of its “active” and “advanced” participants to particular SDGs in a SDGs questionnaire (

UNGC 2016).

The activity of the UNGC headquarters to support the implementation of SDGs has been enormous, ranging from the dissemination of information through publishing methodical materials and guidelines to the creation of an Action Platform. However, still, the previous problems with the UNGC’s (unbalanced) impacts, intensively addressed in the related scholarly debate, make the prospect of the SDGs’ support questionable. Can a shift in the priorities of companies be expected? Will the UNGC’s efforts result in their mobilisation and change their business models towards the SDGs’ implementation? Or does it merely create a new space for instrumental adoption to improve image and reputation? These are the core research questions in the following study of the V4 countries.

3. Materials and Methods

Despite their on-going integration into the Western world and the European Union, the post-transitional V4 countries, still bearing many burdens of their past in terms of business ethics (cf., e.g.,

Kliestik et al. 2018, pp. 792–93), belong to regions with a very low participation rate in the UNGC. With the exception of Poland, the countries can also be considered latecomers, as the first private entities from Hungary only joined in 2005, and from the Czech Republic and Slovakia in 2008, respectively. Until the middle of this decade, the numbers of participants from the V4 had been growing (for details on the dynamics, see

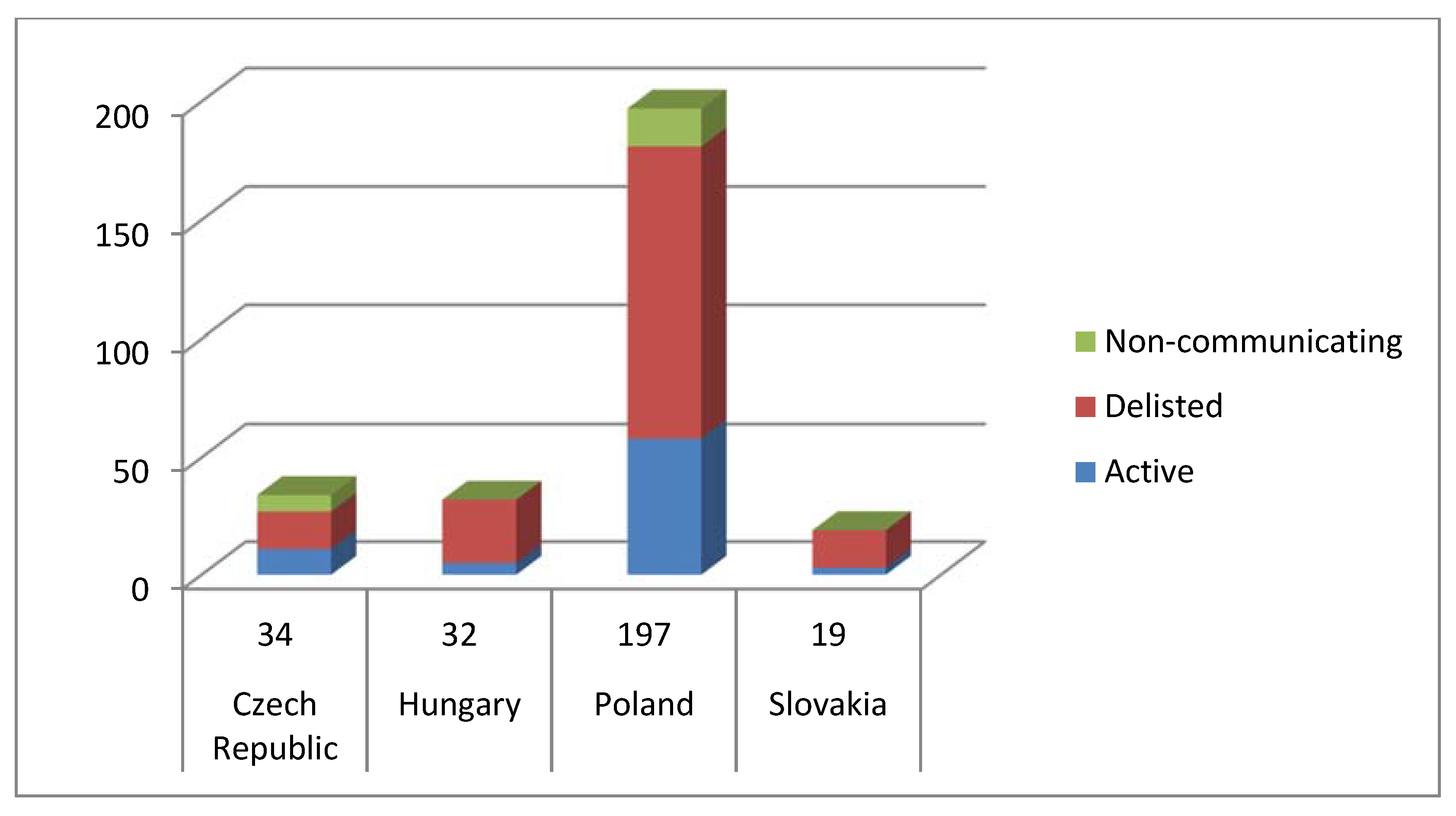

Zemanová and Druláková 2016). However, with the exception of Poland, there has been a substantial decline in engagement since 2016. As a result, the total number of entities involved has almost stagnated, and, as can be clearly seen in

Figure 1, inactive ones (i.e., in the language of the UNGC, delisted and non-communicating) have prevailed over those that regularly submit their COPs, and, thus, remain in the UNGC Participants Database.

By the end of 2019, the total number of active participants from the V4 amounted to 75. However, as the UNGC also enables membership of subjects other than businesses (e.g., academic institutions and non-governmental organisations), only 58 were companies or small and medium enterprises. As of 31 December 2019, the distribution across countries was as follows: The Czech Republic 6 (1 company/5 small and medium enterprises), Hungary 5 (3/2), Poland 45 (22/23), Slovakia 2 (1/1) (

UNGC 2019). This made the region’s participation in the UNGC unique within the global CSR context, as the research so far reports larger firms to be more active in CSR disclosure than smaller ones (

Beck et al. 2018).

As for the SDGs’ performance, all V4 countries scored well in the 2019 SDG index. The Czech Republic qualified in the Top 10 and the other states ranked between the 25th and 29th place (

BSSDSN 2019). However, a closer look reveals that, with a few exceptions (i.e., SDG 1–No Poverty–in the Czech Republic and Slovakia, and SDG 15–Life on Land–in Hungary and Poland), they face persistent challenges in most of the priority areas. Whereas the major ones in all countries relate to SDG 13–Climate Action–and significant ones to SDG 11–Responsible Consumption, in some of them major challenges also remain in SDG 2–Zero Hunger, SDG 4–Quality of Education, SDG 9–Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure, SDG 14–Life below Water and SDG 17–Partnership for the Goals.

To answer the research questions, we first explored V4 countries’ strengths and weaknesses on SDGs with the use of 2019 SDG Dashboards (ibid). We then compared them with the frequency of references to each SDG in the UNGC questionnaire on the relation of activities described in COPs to individual SDGs. The SDG questionnaire requires the identification of individual SDGs covered by COPs from each Active and Advanced Participant, which is the multitude of company participants. To get a more precise picture about the priorities and the role of the business, we then analysed the COPs of V4 companies (i.e., according to UNGC rules, enterprises with at least 250 full-time employees that were as of 1 September 2019 listed as active in the UNGC participants database). This dataset comprised of initially 25 companies and 42 reports. However, it was necessary to exclude 10 Polish companies, as they joined only recently and their first COPs were not due before 31 December 2019, as well as another Polish company whose COPs were not accessible from the database. In total we collected 42 COPs submitted in 2017, 2018 and 2019. This is summarised in

Table 1.

For each COP we recorded which SDGs were declared to be addressed. With the exception of six reports (either in national languages or inaccessible from the UNGC participants database) (

Table 1), we further searched for references to SDGs in their content, using the key word “SDG” and, if no results were shown, we also searched “sustainable development goal”/“sustainable development goals” and then examined the related text.

4. Results

Although the performance of the V4 countries in SDGs is above average, as any other state in the world they are still far from achieving most of them.

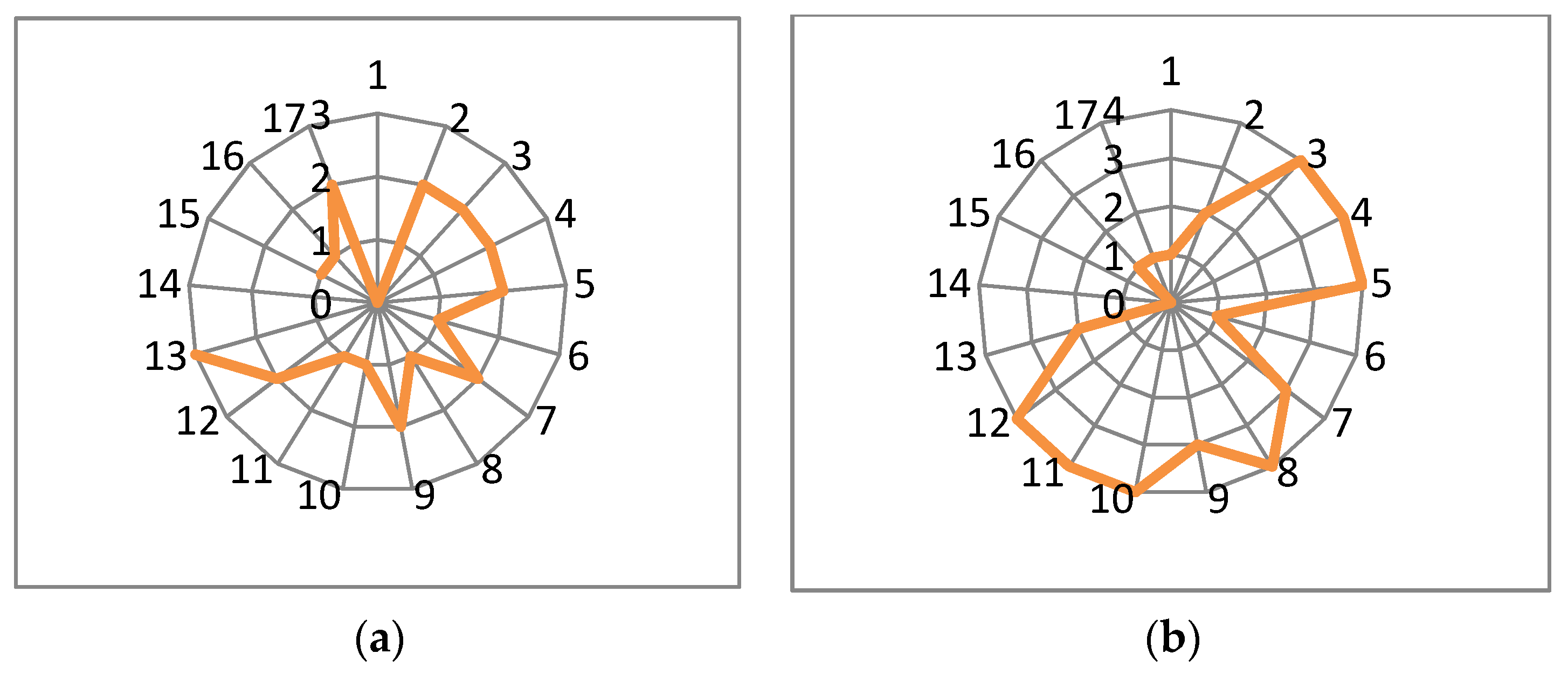

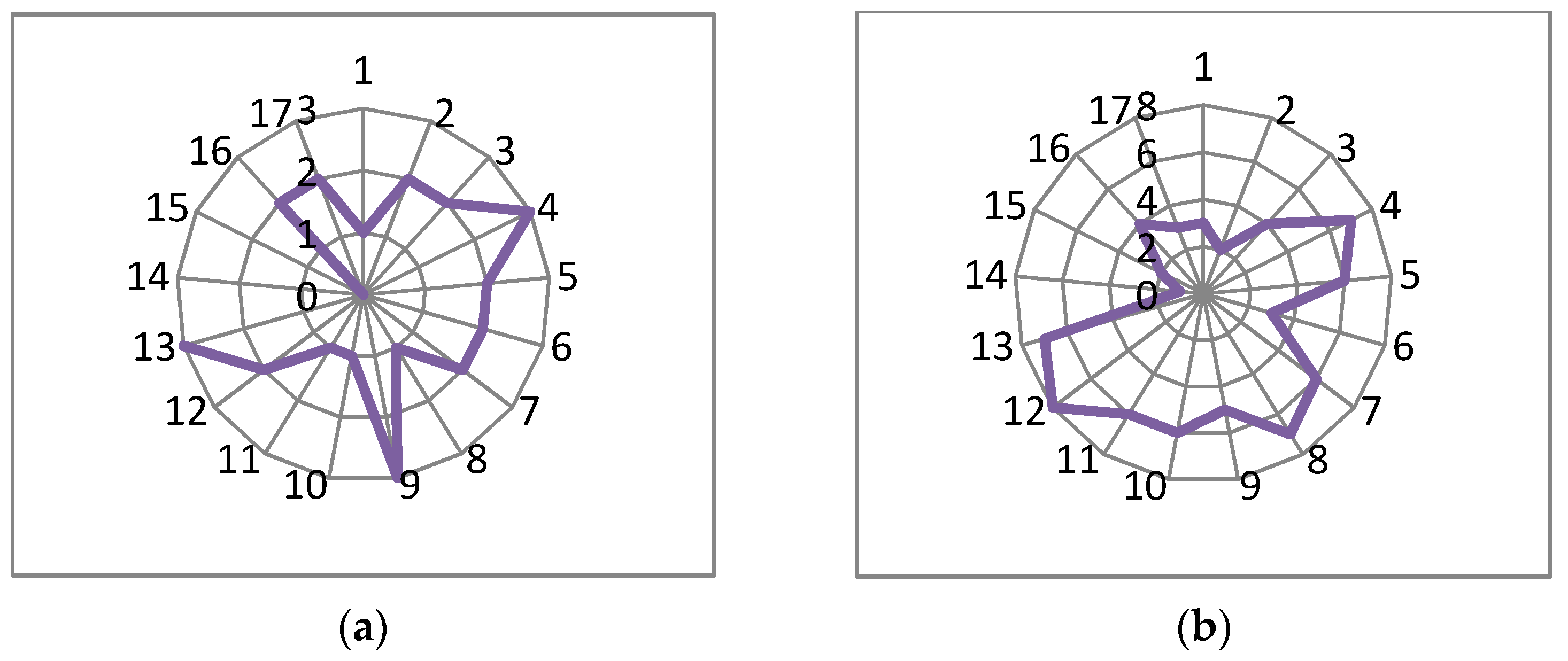

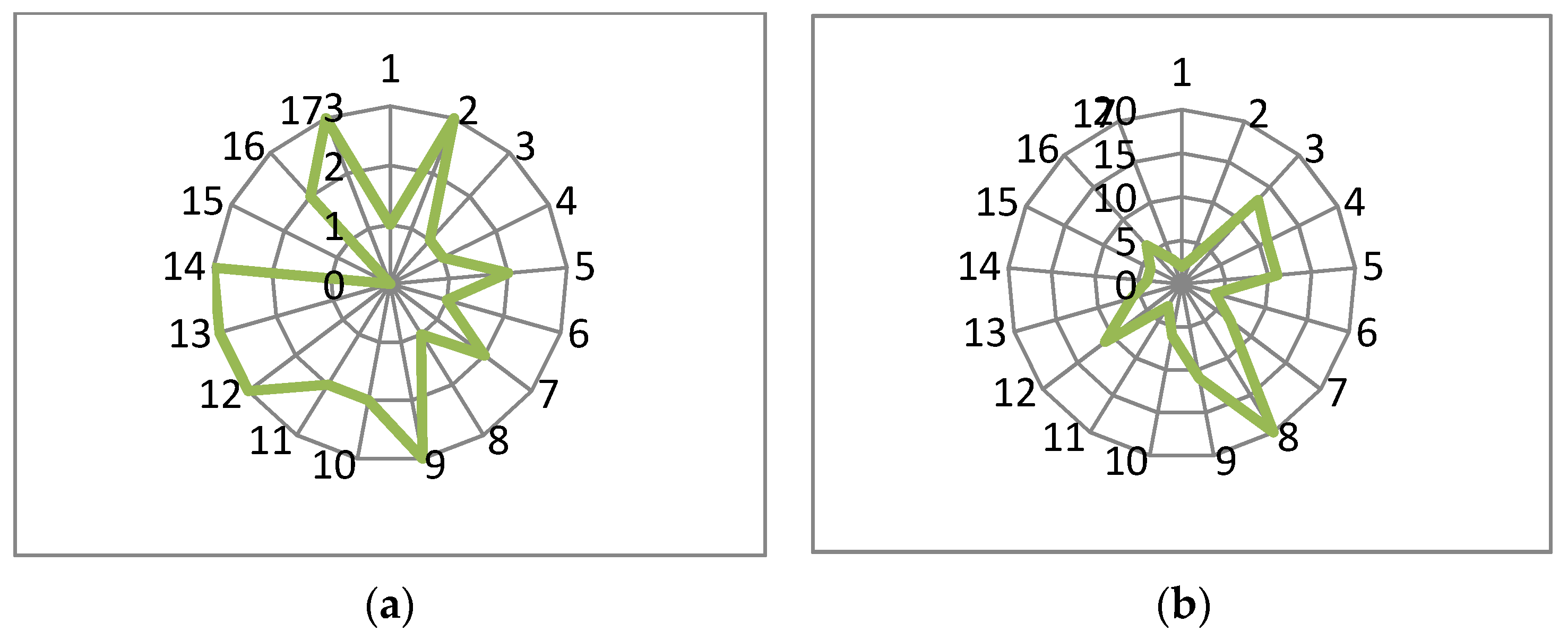

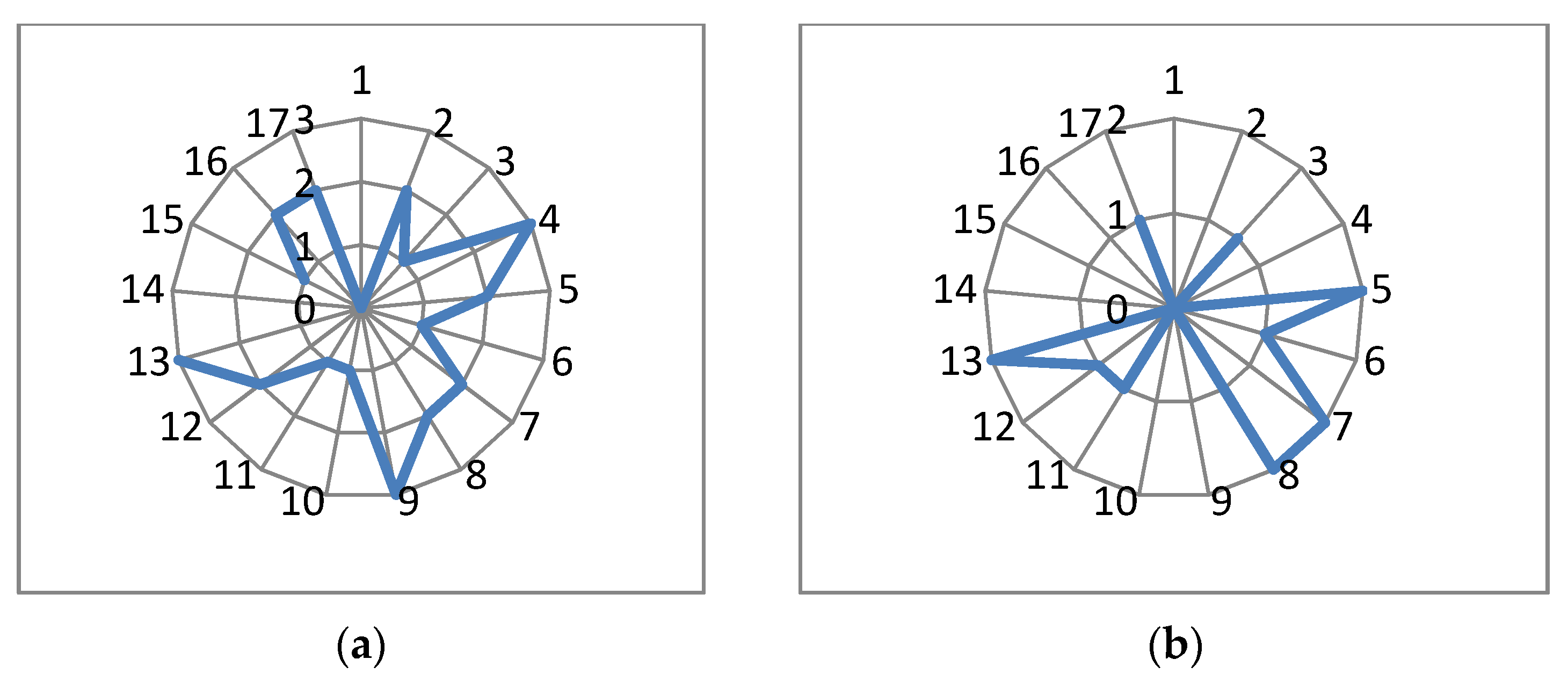

Figure 2a,

Figure 3a,

Figure 4a and

Figure 5a summarise the current situation according to the latest edition of the 2019 Sustainable Development Report (ibid) for each country and SDG separately. Corresponding with Sustainable Development Report methodology, performance is measured by the two worst indicators in each area and divided into four categories: 0—SDG achievement; 1—challenges remain; 2—significant challenges remain; 3—major challenges remain. This means that the best performance is marked by the least and the worst one with the most distance from the centre of the graph.

In the Czech Republic (

Figure 2b), COPs submitted by companies in 2017–2019, according to the responses to the UNGC SDGs questionnaire, tended to address more challenging SDGs for the country, with the exception of SDG 13–Climate action. In addition, despite countries’ better performance in this area, their COPs also covered activities related to SDG 8–Decent work and economic growth, SDG 10–Reduced inequalities, SDG 11–Sustainable cities and communities, and SDG 12–Responsible consumption and Production, which might have correlated with their specific CSR concerns. Similarly, this was also true for Hungarian businesses (

Figure 3b), with more emphasis on SDG 13–Climate action, in comparison to the Czech Republic.

In contrast, data for Poland revealed more divergences (

Figure 4). The country obviously faces major challenges in regard to SDGs 2, 9, 12, 13, 14 and 17. However, only SDG 12 is among those most frequently declared to be covered by activities reported in COPs. Surprisingly, (apart from SDG 12) the highest number of COPs covered SDGs 8, 3, 5 and 4, where the country’s performance was substantially better than in the previous cases.

Unlike the other V4 countries, there is currently only one company participant in the UNGC in Slovakia, with 2 COPs recorded in the Participants database. The data retrieved for this participant (

Figure 5) showed that the range of the SDGs covered changes (which is also the case for many other companies in the dataset) and only four SDGs were addressed in both years, including only one from the most urgent triad for Slovakia. SDG 9–Industry, innovation and infrastructure, where Slovakia faces major challenges, was neglected.

What is more alarming is that only 13 COPs (i.e., approximately 1/3) in our dataset, submitted by seven companies (approximately 40%), contained explicit references to SDGs. However, in most cases these references included a very general description of the SDGs and the 2030 Agenda themselves and a list of taken or planned action. The following parts from the Polish Grupa Lotos and IBA Group’s 2018 COPs are perfect examples:

“We have declared our support for Goal No. 9, regarding building stable infrastructure, promoting sustainable industrialisation and supporting innovation. We want to implement this goal through innovative development projects, for the benefit of our social environment and business.

In addition to the declared Goal No. 9, we actively support the goals of reducing social inequalities, sustainable industry, sustainable management of marine resources, halting losses in biodiversity, productive employment and ensuring sustainable production patterns. Our activities for innovation, including the development of electromobility, and those related to the improvement of efficiency, combine with Goal No. 7 and Goal No. 13.”

“IBA Group employees’ ages range from 20 to 70+ years, which is not typical of young IT companies. Ten of the company’s employees are older than 70. These are top-class mainframe specialists. All employees have access to a benefit package that includes medical care, sports classes, cultural activities, and financial assistance. Former IBA Group employees who retired have access to the benefit package too.”

This makes the commitment and contribution to SDGs within the company segment as well as practical impacts of the UNGC SDGs questionnaire highly questionable. On the other hand, most of the reports with explicit references are of 2018 (5) or the first 8 months of 2019 (6). This might indicate that the obligation to complete the questionnaire results in more interest in SDGs, at least when preparing the subsequent reports, and there might be some space, thus, the project of integration of the UNGC with SDGs might create some space for social learning.

5. Discussion

It is obvious that, as in the case of the UNGC project itself, the impacts on the implementation of SDGs by companies involved in the UNGC in the V4 countries are negligible. The companies from the V4 that qualify as active and advanced participants obviously fulfil their obligation to declare which activities described in their COPs relate to SDGs. Nevertheless, the COPs do not go into the necessary details. This might indicate little interest in SDGs, at least during the completion of COPs, and the ex-post establishment of the linkage to the companies’ business. Combined with the low participation rates from the V4 as well as divergences between the intensity of country challenges and the priorities of the companies related to individual SDGs, the mobilising potential of the UNGC for the implementation of SDGs by the companies from the region is almost zero.

Although some companies respond to the emergence of the SDGs questionnaire in the materials accompanying COPs with the incorporation of general references, they rather link the SDGs with their “business-as-usual” than with future plans and far-reaching changes. Thus, incorporating SDGs for reputational reasons cannot be rejected. This fully corresponds with the previous criticism of the implementation gap (

Fortín and Jolly 2015;

Pingeot 2015), and, in particular, the insufficiencies of COPs themselves (

Coulmont et al. 2017;

Zilic et al. 2019). Nevertheless, findings presented in this study go further, indicating that the expectations related to the importance of the UNGC for the implementation of the SDGs by 2030 might be strongly exaggerated.

As this was only a preliminary study, we are aware of its limitations. Firstly, due to very little interest in the UNGC project in the V4, our dataset was comprehensive but insufficient. We could only map the attitudes of the companies involved, with no possibility of greater generalisation for the implementation of SDGs throughout CSR programmes in the region. Secondly, many of the companies develop their activities both inside and outside V4 countries. Therefore, their commitment to individual SDGs declared in the COP questionnaires does not necessarily have to relate to their country of domicile. However, preventing this possible bias of the records in our dataset would have required that our analysis of the COPs went into substantially more detail, which was beyond the scope of this paper. Last but not least, we did not have any possibility of comparison with other regions, as the research on this topic is in its very initial stage.

6. Conclusions

Without a substantial change soon, the COPs, as a tool for the implementation of the SDGs in the V4, remain of little significance. In order to change this pessimistic outlook, it is necessary to search for ways to activate the relevant stakeholders (the UN, the governments, companies themselves and non-state entities) as fast as possible. The V4 lags significantly behind more advanced European countries and will have to scale-up its efforts.

The prospects of the region remain somewhat uncertain unless new incentives come from the relevant institutional and social background, and crucial stakeholders start performing proactively. In absolute terms, it is currently only Poland that reveals more commitment to the UNGC and its Ten Principles in comparison to other V4 countries. However, the picture is far less optimistic when related to the size of its economy and the total number of companies.

Thus, the existing doubts about the limited contribution of the COPs to the implementation of the SDGs, both globally and locally, seem highly relevant for the V4 region. Moreover, they are further supported by the revealed discrepancies between the broad and comprehensive needs of the countries and the narrow focus and preferences of their companies, concentrating primarily on goals closest to the entrepreneurial activity.

Undoubtedly, the problems with SDGs’ implementation through the UNGC COPs, revealed by the analysis in this paper, should be addressed by further research. There is much room for comparisons on how various UNGC participants link their activities to individual SDGs and address the most urgent challenges of their home states. Furthermore, broader attention should be paid to geographical specifics and patterns to identify both the catalyst of and obstacles to a deeper engagement of business in the ambitious SDGs agenda.

Author Contributions

Methodology, Š.Z.; validation, Š.Z. and R.D.; formal analysis, Š.Z. and R.D.; investigation, Š.Z. and R.D.; data curation, Š.Z. and R.D.; writing—original draft preparation, Š.Z. and R.D.; writing—review and editing, R.D.; visualisation, R.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Faculty of International Relations, University of Economics, Prague.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abdelzaher, Dina, Whitney Fernandez, and William D. Schneper. 2019. Legal rights, national culture and social networks: Exploring the uneven adoption of United Nations Global Compact. International Business Review 28: 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Waris, and Jedrzej G. Frynas. 2018. The role of normative CSR-promoting institutions in stimulating CSR disclosures in developing countries. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 25: 373–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amer, Estefania. 2018. The penalization of non-communicating UN Global Compact’s companies by investors and its implications for this initiative’s effectiveness. Business & Society 57: 255–91. [Google Scholar]

- Ayuso, Silvia, Mercé Roca, Jorge A. Arevalo, and Deepa Aravind. 2016. What Determines Principle-Based Standards Implementation? Reporting on Global Compact Adoption in Spanish Firms. Journal of Business Ethics 133: 553–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, Cornelia, Geoffrey Frost, and Steward Jones. 2018. CSR disclosure and financial performance revisited: A cross-country analysis. Australian Journal of Management 43: 517–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belás, Jaroslav, Přemysl Bartoš, Aleksandr Ključnikov, and Jiří Doležal. 2015. Risk perception differences between micro–, small and medium enterprises. Journal of International Studies 8: 20–30. [Google Scholar]

- Bohatá, Marie. 2005. Czech Republic. In Corporate Social Responsibility across Europe. Edited by André Habisch, Jan Jonker, Martina Wegner and René Schmidpeter. Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 151–66. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Halina Szejnwald, Martin De Jong, and Teodorina Lessidrenska. 2009. The rise of the Global Reporting Initiative: a case of institutional entrepreneurship. Environmental Politics 18: 182–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Jill A., Cynthia Clark, and Anthony F. Buono. 2018. The United Nations global compact: Engaging implicit and explicit CSR for global governance. Journal of Business Ethics 147: 721–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertelsman Stiftung and Sustainable Development Solutions Network. 2019. Sustainable Development Report. Available online: https://s3.amazonaws.com/sustainabledevelopment.report/2019/2019_sustainable_development_report.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2020).

- Coulmont, Michel, Sylvie Berthelot, and Marc–Antoine Paul. 2017. The global compact and its concrete effects. Journal of Global Responsibility 8: 300–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowther, David, and Nicholas Capaldi, eds. 2008. The Ashgate Research Companion to Corporate Social Responsibility. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- De Bakker, Frank GA, Peter Groenewegen, and Frank Den Hond. 2005. A bibliometric analysis of 30 years of research and theory on corporate social responsibility and corporate social performance. Business & society 44: 283–317. [Google Scholar]

- Fekete, Láczló. 2005. Hungary: Social Welfare Lagging Behind Economic Growth. In Corporate Social Responsibility Across Europe. Edited by André Habisch, Jan Jonker, Martina Wegner and René Schmidpeter. Berlin: Springer, pp. 141–50. [Google Scholar]

- Fortín, Carlos, and Richard Jolly. 2015. The United Nations and Business: Towards New Modes of Global Governance? IDS Bulletin 46: 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanggraeni, Dewi, Beata Ślusarczyk, Liyu Adhi Kasari Sulunk, and Athor Subroto. 2019. The Impact of Internal, External and Enterprise Risk Management on the Performance of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises. Sustainability 11: 2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, Dima, and Ramez Mirshak. 2007. Corporate social responsibility (CSR): Theory and practice in a developing country context. Journal of Business Ethics 72: 243–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jastram, Sarah M., and Jenny Klingenberg. 2018. Assessing the outcome effectiveness of multi-stakeholder initiatives in the field of corporate social responsibility—The example of the United Nations Global Compact. Journal of Cleaner Production 189: 775–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kliestik, Tomas, Maria Misankova, Katarina Valaskova, and Lucia Svabova. 2018. Bankruptcy prevention: new effort to reflect on legal and social changes. Science and Engineering Ethics 24: 791–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenssen, Gilbert, Wojciech Gasparski, Boleslaw Rok, Peter Lacy, and Anna Lewicka-Strzalecka. 2006. Opportunities and limitations of CSR in the postcommunist countries: Polish case. Corporate Governance 6: 440–48. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, Alwyn. 2017. Global corporate responsibility in domestic context: Lateral decoupling and organizational responses to globalization. Economy and Society 46: 229–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marimon, Frederic, María del Mar Alonso-Almeida, Martha del Pilar Rodríguez, and Klender Aimer Cortez Alejandro. 2012. The worldwide diffusion of the global reporting initiative: What is the point? Journal of Cleaner Production 33: 132–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orzes, Guido, Antonella M. Moretto, Maling Ebrahimpour, Marco Sartor, Mattia Moro, and Matteo Rossi. 2018. United Nations Global Compact: Literature review and theory–based research agenda. Journal of Cleaner Production 177: 633–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pingeot, Lou. 2015. In Whose Interest? The UN’s Strategic Rapprochement with Business in the Sustainable Development Agenda. Globalizations 13: 188–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, Stefan, and Marcus Wagner. 2006. Integrative management of sustainability performance, measurement and reporting. International Journal of Accounting, Auditing and Performance Evaluation 3: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schembera, Stefan. 2018. Implementing corporate social responsibility: Empirical insights on the impact of the UN Global Compact on its business participants. Business & Society 57: 783–825. [Google Scholar]

- Shoji, Mariko. 2015. Global Accountability of Transnational Corporations. Journal of East Asia and International Law 8: 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Steurer, Reinhard, and Astrid Konrad. 2009. Business–society relations in Central–Eastern and Western Europe: How those who lead in sustainability reporting bridge the gap in corporate (social) responsibility. Scandinavian Journal of Management 25: 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teck, Tan Seng, Selvamalar Ayadurai, and William Chua. 2019. A Contextual Review on the Evolution of Corporate Social Responsibility. Journal of Management and Sustainability 9: 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nation Global Compact. 2014. White Paper. The Role of Business and Finance in Supporting the Post-2015 Agenda. Available online: https://www.unglobalcompact.org/docs/news_events/9.6/Post2015_WhitePaper_2July14.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2020).

- United Nation Global Compact. 2016. White Paper. The UN Global Compact Ten Principles and the Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://www.business-humanrights.org/sites/default/files/documents/UNGCPrinciples_SDGs_White_Paper.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2020).

- United Nations Global Compact. 2018. Progress Report. Available online: https://www.unglobalcompact.org/library/5637 (accessed on 10 January 2020).

- United Nations Global Compact. 2019. Participants Database. Available online: https://www.unglobalcompact.org/what-is-gc/participants (accessed on 10 January 2020).

- Wettstein, Florian, Elisa Giuliani, Grazia D. Santangelo, and Günter K. Stahl. 2019. International business and human rights: A research agenda. Journal of World Business 54: 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Oliver F., ed. 2014. Sustainable Development: The UN Millennium Development Goals, the UN Global Compact, and the Common Good. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Oliver F. 2018. Restorying the Purpose of Business: An Interpretation of the Agenda of the UN Global Compact. African Journal of Business Ethics 12: 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemanová, Štěpánka, and Radka Druláková. 2016. Globalization and Its Socio-Economic Consequences. Paper presented at the 16th International Scientific Conference, ZU—University of Žilina, Rajecke Teplice, Slovak Republic, 5–6 October 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zilic, Ivana, Helen LaVan, and Lori S. Cook. 2019. Assessing UNGC pharmaceutical signatories stakeholders using big data. Business and Society Review 124: 201–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).