The Effects of Environmental Regulation on the Singapore Stock Market

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Methodology

3.1. Measurement of Abnormal Returns

3.2. Robustness Checks

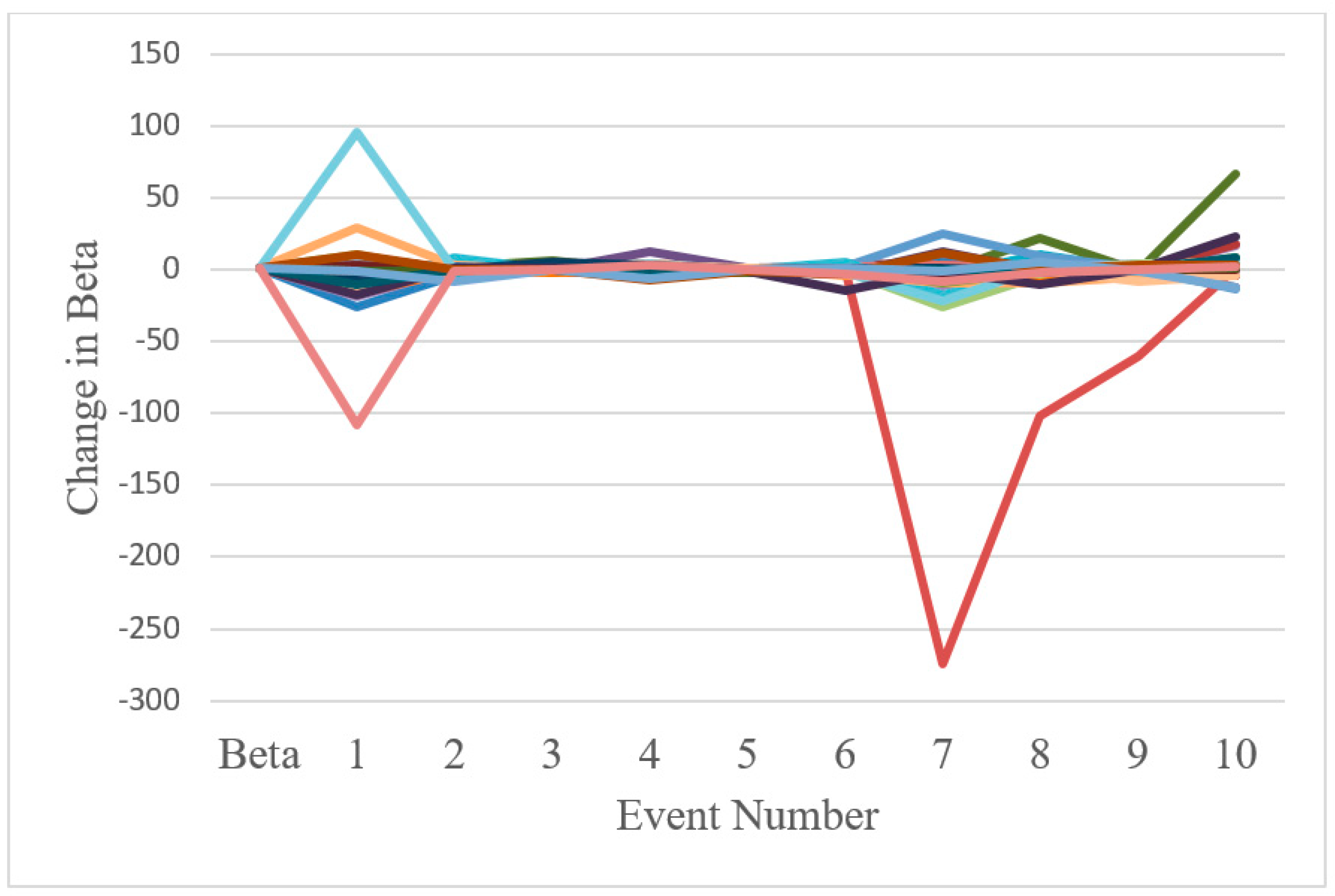

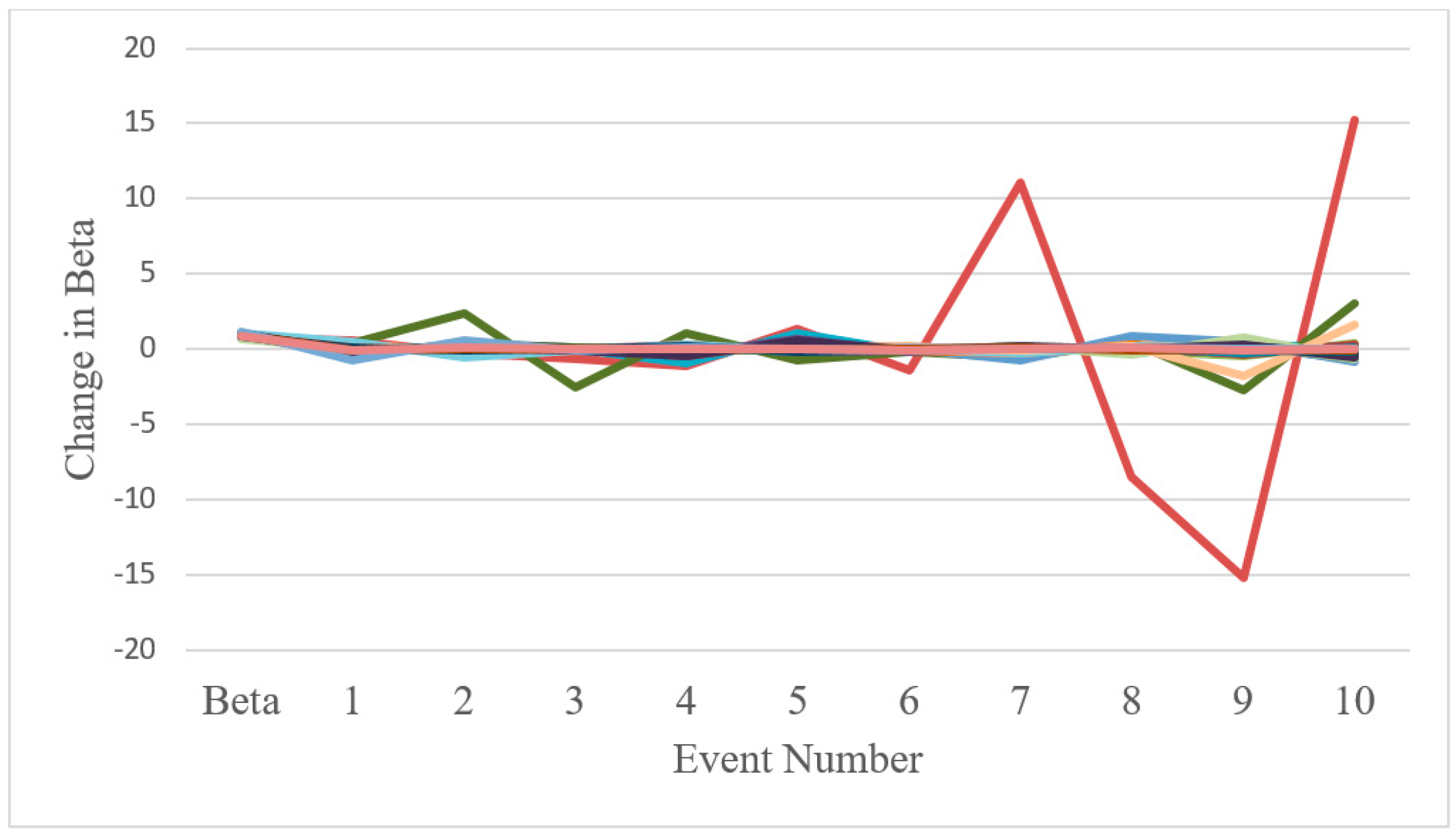

3.3. Estimating Changes in Systematic Risk

4. Data and Results

4.1. Data and an Overview

4.2. Sectors Reacting Negatively

4.3. Sectors Reacting Positively

4.4. Mixed and No Reactions

4.5. The Pattern of CARs

4.6. The Diamond Risk Structure

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abolhosseini, Shahrouz, and Almas Heshmati. 2014. The main support mechanisms to finance renewable energy development. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 40: 876–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, Sankarshan. 1993. Value of latent information: Alternative event study methods. Journal of Finance 48: 363–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, Frank E. 1992. Reducing Toxic Waste Produces Quick Results. The Wall Street Journal 11: B1. [Google Scholar]

- Ameer, Rashid, and Radiah Othman. 2012. Sustainability practices and corporate financial performance: A study based on the top global corporations. Journal of Business Ethics 108: 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ataullah, Ali, Xiaojing Song, and Mark Tippett. 2011. A modified Corrado test for assessing abnormal security returns. The European Journal of Finance 17: 589–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barraclough, Kathryn, David T. Robinson, Tom Smith, and Robert E. Whaley. 2013. Using option prices to infer overpayments and synergies in MandA transactions. Review of Financial Studies 26: 695–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagat, Sanjai, Ming Dong, David Hirshleifer, and Robert Noah. 2005. Do tender offers create value? New methods and evidence. Journal of Financial Economics 76: 3–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borochin, Paul. 2014. When does a merger create value? Using option prices to elicit market beliefs. Financial Management 43: 445–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borochin, Paul, and Joseph Golec. 2016. Using options to measure the full value-effect of an event: application to Obamacare. Journal of Financial Economics 120: 169–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragdon, Joseph H., and John A. T. Marlin. 1972. Is pollution profitable? Risk Management 19: 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, Michael J. 1990. Latent assets. Journal of Finance 45: 709–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Stephen J., and Jerold B. Warner. 1985. Using daily stock returns: the case of event studies. Journal of Financial Economics 14: 3–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Jie, Moon H. Song, and Ralph A. Walkling. 2011. Anticipation, acquisitions, and bidder returns: industry shocks and the transfer of information across rivals. Review of Financial Studies 24: 2242–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaplinsky, Susan, and Robert S. Hansen. 1993. Partial anticipation, the flow of information and the economic impact of corporate debt sales. Review of Financial Studies 6: 709–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesney, Marc, Ganna Reshetar, and Mustafa Karaman. 2011. The impact of terrorism on financial markets: An empirical study. Journal of Banking and Finance 35: 253–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criscuolo, Chiara, and Carlo Menon. 2015. Environmental policies and risk finance in the green sector: Cross-country evidence. Energy Policy 83: 38–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christainsen, Gregory B., and Robert H. Haveman. 1981. The contribution of environmental regulations to the slowdown in productivity growth. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 8: 381–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrado, Charles J. 1989. A non-parametric test for abnormal security price performance in event studies. Journal of Financial Economics 23: 385–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowell, Glen, Stuart Hart, and Bernard Yeung. 2000. Do corporate global environmental standards create or destroy market value. Management Science 46: 1059–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, Eugene, and Kenneth French. 1993. Common risk factors in the returns on stocks and bonds. Journal of Financial Economics 33: 3–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, Eugene, and Kenneth French. 2015. A five-factor asset pricing model. Journal of Financial Economics 116: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, Stanley J., Peter A. Soyka, and Paul G. Ameer. 1997. Does improving a firm’s environmental management system and environmental performance result in a higher stock price? The Journal of Investing Winter 6: 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnaut, Ross. 2018. The Garnaut Climate Change Review. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, Wayne, and Ron Shadbegian. 1993. Environmental Regulation and Manufacturing Productivity at the Plant Level. NBER Working Papers, No 4321. Cambridge, MA, USA: NBER. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, Kartick. 2018. Environmental sustainability and implied cost of equity: International evidence. Journal of Business Ethics 147: 343–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halkos, George, and Anastasios Sepetis. 2007. Can capital markets respond to environmental policy of firms? Evidence from Greece. Ecological Economics 63: 578–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, James T. 1995. Pollution as news: media and stock market reactions to the toxics release inventory data. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 28: 98–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klassen, Robert D., and Curtis P. McLaughlin. 1996. The impact of environmental management on firm performance. Management Science 42: 1199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanoie, Paul, Michel Patry, and Richard Lajeunesse. 2008. Environmental regulation and productivity: Testing the porter hypothesis. Journal of Productivity Analysis 30: 121–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnenluecke, Martina K., Jacqueline Birt, and Andrew Griffiths. 2015a. The role of accounting in supporting adaptation to climate change. Accounting and Finance 55: 607–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnenluecke, Martina K., Cristyn Meath, Saphira Rekker, Baljit K. Sidhu, and Tom Smith. 2015b. Divestment from fossil fuel companies: Confluence between policy and strategic viewpoints. Australian Journal of Management 40: 478–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnenluecke, Martina K., Xiaoyan Chen, Xin Ling, Tom Smith, and Yushu Zhu. 2016. Emerging trends in Asia-Pacific finance research: A review of recent influential publications and a research agenda. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal 36: 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malatesta, Paul H., and Rex Thompson. 1985. Partially anticipated events: a model of stock price reactions with an application to corporate acquisitions. Journal of Financial Economics 14: 237–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, Jean B., Alison Sundgren, and Thomas Schneeweis. 1988. Corporate social responsibility and firm financial performance. Academy of Management Journal 31: 854–72. [Google Scholar]

- Nandy, Monomita, and Suman Lodh. 2012. Do banks value the eco-friendliness of firms in their corporate lending decision? Some empirical evidence. International Review of Financial Analysis 25: 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto, Jaime, Óscar Carpintero, and Luis J. Miguel. 2018. Less than 2 °C? An Economic-Environmental Evaluation of the Paris Agreement. Ecological Economics 146: 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathania, Rohit, and Arnab Bose. 2014. An Analysis of the Role of Finance in Energy Transitions. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment 4: 266–71. [Google Scholar]

- Pham, Huy N. A., Vikash Ramiah, and Imad Moosa. 2019a. The effects of environmental regulation on the stock market: The French experience. Accounting and Finance. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, Huy, Van Nguyen, Vikash Ramiah, Kashif Saleem, and Nisreen Moosa. 2019b. The effects of the Paris climate agreement on stock markets: evidence from the German stock market. Applied Economics 51: 6068–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhala, Nagpurnanand R. 1997. Conditional methods in event studies and an equilibrium justification for standard event-study procedures. Review of Financial Studies 10: 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramiah, Vikash, Belinda Martin, and Imad Moosa. 2013. How does the stock market react to the announcement of green policies? Journal of Banking and Finance 37: 1747–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramiah, Vikash, Jacopo Pichelli, and Imad Moosa. 2015a. The effects of environmental regulation on corporate performance: a Chinese perspective. Review of Pacific Basin Financial Markets and Policies 18: 1550026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramiah, Vikash, Jacopo Pichelli, and Imad Moosa. 2015b. Environmental regulation, the Obama effect and the stock market: some empirical results. Applied Economics 47: 725–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidheiny, Stephan. 1992. Changing Course: A Global Business Perspective on Development and the Environment. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sharfman, Mark P., and Chitru S. Fernando. 2008. Environmental risk management and the cost of capital. Strategic Management Journal 29: 569–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Moon H., and Ralph A. Walkling. 2000. Abnormal returns to rivals of acquisition targets: A test of the “acquisition probability hypothesis”. Journal of Financial Economics 55: 143–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, Stephen, Timothy J. Foxon, and Ronan Bolton. 2017. Investing in low-carbon transitions: energy finance as an adaptive market. Climate Policy 17: 280–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, Richard B. 1993. Environmental Regulation and International Competitiveness. The Yale Law Journal 102: 2039–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, Ajay. 2004. Option pricing on stocks in mergers and acquisitions. Journal of Finance 59: 795–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veith, Stefan, Jörg R. Werner, and Jochen Zimmermann. 2009. Capital market response to emission rights returns: evidence from the European power sector. Energy Economics 31: 605–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, Kent, Na Ni, and Weidong Huo. 2014. Is the red dragon green? An examination of the antecedents and consequences of environmentally proactivity in China. Journal of Business Ethics 125: 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walley, Noah, and Bradley Whitehead. 1994. It’s Not Easy Being Green. Harvard Business Review 72: 46–52. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Guojian, Wenju Cai, Bolan Gan, Lixin Wu, Agus Santoso, Xiaopei Lin, Zhaohui Chen, and Michael J. McPhaden. 2017. Continued increase of extreme El Niño frequency long after 1.5 °C warming stabilization. Nature Climate Change 7: 568–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, Mark A. 1996. Corporate Environmental Responsibility and Shareholder Value. Virginia: McIntire School of Commerce, University of Virginia, Unpublished Paper. [Google Scholar]

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 12 April 2006 | 1 | Singapore ratified the Kyoto Protocol |

| 11 July 2006 | 2 | Date of entry into force of Singapore into the Kyoto Protocol |

| 12 July 2012 | 3 | The National Climate Change Secretariat released the National Climate Change Strategy (NCCS-2012), outlining Singapore’s plans to address climate change through a whole-of-nation approach |

| 24 September 2014 | 4 | Singapore ratified the Doha Amendment to the Kyoto Protocol, an international climate change agreement that formalises the nation’s commitments from 2013 to 2020 |

| 8 November 2014 | 5 | Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong unveiled the Sustainable Singapore Blueprint (SSB) 2015 |

| 22 April 2016 | 6 | Singapore signed the Paris Agreement |

| 21 September 2016 | 7 | Singapore ratified the Paris Agreement |

| 20 February 2017 | 8 | Singapore government announced a new carbon tax which will come into force by 2019 |

| 19 February 2018 | 9 | All facilities producing 25,000 tonnes or more of greenhouse gas emissions in a year will have to pay a carbon tax from 2020, Finance Minister Heng Swee Keat announced |

| 20 March 2018 | 10 | The carbon pricing bill, which sets out a framework for implementing the carbon tax, including the measurement, reporting and verification requirements, was passed in Parliament |

| Robustness Tests | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAPM | Corrado | Chesney | Market Integration | Fama–French 5 Factor | ||||||

| Sector | Date | AR (%) | t-Stat | tCorrado | CP | t-Stat | AR (%) | t-Stat | AR (%) | t-Stat |

| Positive Reactions | ||||||||||

| Aerospace and Defense | 12 April 2006 | 3.27 | 2.46 | 2.33 | 0.13 | 1.26 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.21 | −0.16 |

| 11 July 2006 | 3.72 | 2.78 | −0.48 | 0.47 | 0.09 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.02 | −0.01 | |

| Food Producers | 19 February 2018 | 1.75 | 2.54 | 2.82 | 0.10 | 1.48 | −0.43 | −0.74 | −0.05 | −0.08 |

| Food and Drug Retailers | 19 February 2018 | 1.17 | 2.07 | 1.92 | 0.04 | 2.15 | 0.11 | 0.21 | 0.15 | 0.26 |

| Gas, Water and Multiutilities | 19 February 2018 | 2.45 | 2.81 | 2.77 | 0.30 | 0.55 | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.66 | 0.79 |

| Mining | 19 February 2018 | 3.92 | 2.25 | 2.06 | 0.32 | 0.49 | 0.28 | 0.17 | 0.77 | 0.44 |

| Mobile Telecommunication | 19 February 2018 | 1.74 | 2.60 | 2.19 | 0.37 | 0.34 | −0.74 | −1.18 | −1.04 | −1.66 |

| Pharmaceuticals and Biotechnology | 12 July 2012 | 19.16 | 6.38 | 0.31 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.13 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.02 |

| Real Estate Investment and Services | 19 February 2018 | 1.31 | 1.97 | 2.57 | 0.11 | 1.43 | 0.69 | 1.22 | 0.80 | 1.32 |

| Real Estate Investment Trust | 19 February 2018 | 0.82 | 2.49 | 1.77 | 0.06 | 1.92 | −0.38 | −1.57 | −0.29 | −1.17 |

| Technology Hardware and Equipment Services | 24 September 2014 | 2.05 | 2.14 | 0.73 | 0.02 | 2.69 | −1.29 | −1.27 | −1.31 | −1.32 |

| Negative Reactions | ||||||||||

| Beverages | 12 July 2012 | −2.12 | −1.98 | −2.40 | 0.47 | 0.09 | −0.45 | −0.42 | −0.57 | −0.53 |

| Chemicals | 12 April 2006 | −5.20 | −2.32 | −1.48 | 0.04 | 2.28 | 0.04 | 0.02 | −0.22 | −0.11 |

| Electrical Equipment and Services | 10 November 2014 | −2.49 | −2.34 | −0.82 | 0.08 | 1.67 | 1.33 | 1.43 | 1.14 | 1.18 |

| 22 April 2016 | −2.74 | −2.11 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 3.22 | 1.02 | 0.82 | 0.91 | 0.75 | |

| Forestry and Papers | 20 February 2017 | −4.92 | −2.02 | −1.84 | 0.14 | 1.23 | −2.76 | −1.28 | −2.73 | −1.25 |

| Industrial Engineering | 11 July 2006 | −2.34 | −2.20 | −1.20 | 0.14 | 1.19 | −0.41 | −0.40 | −0.13 | −0.14 |

| 10 November 2014 | −1.36 | −2.15 | −1.30 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.78 | 1.25 | 0.56 | 0.89 | |

| Industrial Metals and Mining | 12 July 2012 | −4.14 | −2.64 | −0.50 | 0.33 | 0.48 | −0.65 | −0.43 | −0.75 | −0.50 |

| Leisure Goods | 24 September 2014 | −4.44 | −2.11 | −1.74 | 0.50 | 0.01 | −2.91 | −1.35 | −3.32 | −1.52 |

| Media | 12 July 2012 | −12.98 | −4.83 | −1.36 | 0.50 | 0.00 | −1.08 | −0.45 | −1.26 | −0.51 |

| Travel and Leisure | 24 September 2014 | −1.53 | −2.12 | −0.44 | 0.15 | 1.16 | 1.49 | 2.24 | 1.34 | 1.98 |

| Mixed Reactions | ||||||||||

| General Retailers | 21 September 2016 | 2.60 | 2.20 | 0.96 | 0.08 | 1.61 | −0.73 | −0.65 | −0.75 | −0.69 |

| 20 March 2018 | −2.62 | −2.59 | −1.19 | 0.45 | 0.13 | −0.33 | −0.33 | 0.33 | 0.31 | |

| Healthcare Equipment and Services | 22 April 2016 | −3.82 | −2.35 | 0.62 | 0.43 | 0.18 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.32 | −0.20 |

| 21 September 2016 | 3.74 | 2.90 | 0.81 | 0.08 | 1.69 | 2.10 | 1.40 | 1.99 | 1.33 | |

| Household Goods and Home Construction | 20 February 2017 | 3.70 | 2.27 | 1.22 | 0.01 | 3.18 | 1.61 | 1.04 | 1.68 | 1.07 |

| 19 February 2018 | −2.39 | −2.01 | 0.24 | 0.10 | 1.50 | 0.53 | 0.40 | 0.30 | 0.22 | |

| Robustness Tests | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAPM | Chesney | Market Integration | Fama−French 5 Factor | ||||||

| Sector | Date | CAR(−5) | t-Stat | CP | t-Stat | CAR(−5) (%) | t-Stat | CAR(−5) (%) | t-Stat |

| Positive Reactions | |||||||||

| Alternative Energy | 20 March 2018 | 126.09 | 2.77 | 0.47 | 0.08 | −0.09 | −0.08 | −0.04 | −0.04 |

| Automobiles and Parts | 20 February 2017 | 6.44 | 2.42 | 0.50 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 1.33 | 0.09 | 1.33 |

| 19 February 2018 | 4.31 | 2.02 | 0.03 | 2.36 | 0.03 | 0.53 | 0.03 | 0.45 | |

| Banks | 19 February 2018 | 3.88 | 2.02 | 0.02 | 2.75 | 0.09 | 2.78 | 0.07 | 2.01 |

| Beverages | 22 April 2016 | 20.46 | 2.93 | 0.03 | 2.39 | 0.21 | 1.48 | 0.19 | 1.36 |

| Electrical Equipment and Services | 20 February 2017 | 5.96 | 2.30 | 0.36 | 0.37 | 0.07 | 0.93 | 0.06 | 0.76 |

| Forestry and Papers | 22 April 2016 | 7.34 | 2.18 | 0.02 | 2.85 | 0.05 | 0.66 | 0.05 | 0.67 |

| 20 February 2017 | 17.28 | 3.62 | 0.08 | 1.65 | 0.07 | 0.68 | 0.07 | 0.70 | |

| General Industrials | 11 July 2006 | 6.63 | 2.07 | 0.15 | 1.18 | 0.02 | 0.25 | 0.03 | 0.39 |

| General Retailers | 20 February 2017 | 4.02 | 1.99 | 0.01 | 3.81 | 0.03 | 0.52 | 0.02 | 0.35 |

| Healthcare Equipment and Services | 12 July 2012 | 9.51 | 2.67 | 0.02 | 2.77 | 0.06 | 0.97 | 0.11 | 1.64 |

| Industrial Engineering | 20 February 2017 | 3.91 | 2.47 | 0.17 | 1.06 | 0.08 | 1.91 | 0.07 | 1.67 |

| Industrial Metals and Mining | 12 April 2006 | 4.79 | 2.01 | 0.06 | 1.82 | 0.08 | 1.24 | 0.05 | 0.81 |

| 21 September 2016 | 4.92 | 2.13 | 0.11 | 1.38 | 0.06 | 0.95 | 0.06 | 0.97 | |

| Leisure Goods | 21 September 2016 | 10.76 | 2.38 | 0.30 | 0.56 | 0.06 | 0.43 | 0.07 | 0.46 |

| Life Insurance | 24 September 2014 | 3.67 | 2.06 | 0.45 | 0.13 | 0.03 | 0.94 | 0.04 | 1.19 |

| 19 February 2018 | 4.28 | 2.05 | 0.41 | 0.23 | 0.04 | 0.93 | 0.04 | 0.93 | |

| Media | 22 April 2016 | 9.06 | 2.04 | 0.08 | 1.61 | 0.03 | 0.17 | 0.01 | 0.05 |

| 19 February 2018 | 7.28 | 2.13 | 0.04 | 2.29 | 0.10 | 1.15 | 0.08 | 0.90 | |

| Mining | 12 April 2006 | 13.71 | 2.45 | 0.01 | 3.21 | 0.19 | 1.20 | 0.11 | 0.73 |

| Nonlife Insurance | 12 July 2012 | 5.50 | 2.12 | 0.02 | 2.72 | −0.01 | −0.23 | 0.01 | 0.11 |

| Oil and Gas Producers | 11 July 2006 | 20.74 | 2.42 | 0.12 | 1.34 | 0.12 | 0.67 | 0.12 | 0.65 |

| Personal Goods | 10 November 2014 | 7.17 | 2.31 | 0.01 | 3.90 | −0.06 | −0.64 | −0.08 | −0.93 |

| 20 February 2017 | 12.78 | 3.67 | 0.47 | 0.08 | 0.12 | 1.57 | 0.14 | 1.73 | |

| Real Estate Investment and Services | 21 September 2016 | 4.05 | 3.35 | 0.13 | 1.29 | 0.04 | 1.44 | 0.05 | 1.51 |

| Software | 10 November 2014 | 9.63 | 2.92 | 0.01 | 3.98 | −0.03 | −0.37 | −0.03 | −0.35 |

| Fixed Line Telecommunication | 20 February 2017 | 14.93 | 5.49 | 0.30 | 0.55 | 0.13 | 1.91 | 0.13 | 2.01 |

| 19 February 2018 | 11.94 | 3.65 | 0.03 | 2.56 | 0.23 | 2.90 | 0.22 | 2.83 | |

| Travel and Leisure | 24 September 2014 | 4.58 | 3.10 | 0.00 | 7.44 | 0.03 | 0.91 | 0.03 | 1.07 |

| 20 February 2017 | 5.65 | 2.97 | 0.02 | 2.61 | 0.07 | 1.08 | 0.06 | 1.00 | |

| Negative Reactions | |||||||||

| Mobile Telecommunications | 19 February 2018 | −3.55 | −2.73 | 0.49 | 0.01 | −0.03 | −1.09 | −0.04 | −1.56 |

| Real Estate Investment Trust | 12 April 2006 | −7.18 | −3.56 | 0.19 | 0.97 | −0.01 | −0.29 | 0.00 | −0.08 |

| Mixed Reactions | |||||||||

| Aerospace and Defense | 24 September 2014 | −6.50 | −2.10 | 0.47 | 0.07 | −0.05 | −0.60 | −0.05 | −0.67 |

| 20 March 2018 | 7.78 | 2.01 | 0.02 | 2.76 | 0.10 | 0.95 | 0.09 | 0.87 | |

| Robustness Tests | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAPM | Chesney | Market Integration | Fama−French 5 Factor | ||||||

| Sector | Date | CAR5 | t-Stat | CP | t-Stat | CAR5 (%) | t-Stat | CAR5 (%) | t-Stat |

| Positive Reactions | |||||||||

| Alternative Energy | 12 April 2006 | 43.10 | 2.57 | 0.02 | 2.63 | 0.24 | 0.53 | 0.35 | 0.79 |

| Chemicals | 12 April 2006 | 16.78 | 3.84 | 0.03 | 2.36 | 0.16 | 1.68 | 0.14 | 1.49 |

| Construction and Materials | 12 April 2006 | 7.18 | 2.46 | 0.27 | 0.64 | 0.14 | 2.12 | 0.11 | 1.73 |

| Electrical Equipment and Services | 12 April 2006 | 6.07 | 2.51 | 0.28 | 0.63 | 0.03 | 0.63 | 0.03 | 0.54 |

| Financial Services | 12 April 2006 | 4.85 | 1.97 | 0.14 | 1.24 | 0.03 | 0.47 | 0.03 | 0.44 |

| Food Producers | 12 April 2006 | 5.63 | 2.24 | 0.10 | 1.44 | 0.07 | 1.05 | 0.03 | 0.57 |

| Food and Drug Retailers | 19 February 2018 | 2.73 | 2.12 | 0.06 | 1.94 | 0.04 | 1.65 | 0.04 | 1.40 |

| Healthcare Equipment and Services | 12 April 2006 | 7.95 | 2.06 | 0.03 | 2.47 | 0.14 | 1.23 | 0.15 | 1.39 |

| Industrial Engineering | 12 April 2006 | 6.06 | 2.79 | 0.32 | 0.50 | 0.06 | 1.34 | 0.05 | 1.30 |

| Life Insurance | 12 July 2012 | 7.30 | 2.83 | 0.06 | 1.91 | 0.07 | 1.74 | 0.10 | 2.34 |

| Media | 12 April 2006 | 8.06 | 2.65 | 0.43 | 0.19 | 0.10 | 1.16 | 0.08 | 1.00 |

| 12 July 2012 | 8.19 | 2.14 | 0.50 | 0.00 | −0.06 | −0.56 | −0.04 | −0.35 | |

| Oil and Gas Producers | 12 April 2006 | 23.75 | 3.01 | 0.12 | 1.31 | 0.26 | 3.13 | 0.17 | 2.18 |

| Technological Hardware and Equipment | 21 September 2016 | 7.33 | 2.93 | 0.01 | 3.09 | 0.07 | 0.95 | 0.08 | 1.10 |

| Negative Reactions | |||||||||

| Mobile Telecommunications | 11 July 2006 | −5.10 | −2.85 | 0.02 | 2.84 | −0.05 | −1.40 | −0.05 | −1.25 |

| Nonlife Insurance | 12 July 2012 | −6.05 | −2.37 | 0.00 | 4.29 | −0.01 | −0.23 | 0.01 | 0.11 |

| Personal Goods and Home Construction | 19 February 2018 | −8.36 | −2.87 | 0.12 | 1.30 | −0.07 | −0.89 | −0.09 | −1.17 |

| Software | 10 November 2014 | −6.78 | −2.05 | 0.06 | 1.87 | 0.02 | 0.22 | 0.02 | 0.21 |

| 22 April 2016 | −14.16 | −2.29 | 0.40 | 0.26 | −0.06 | −0.36 | −0.09 | −0.50 | |

| Mixed Reactions | |||||||||

| Industrial Metals and Mining | 12 April 2006 | 8.16 | 3.44 | 0.02 | 2.74 | 0.08 | 1.24 | 0.05 | 0.81 |

| 19 February 2018 | −6.88 | −2.26 | 0.07 | 1.80 | −0.05 | −0.74 | −0.06 | −0.83 | |

| Electricity | 12 April 2006 | 19.92 | 2.75 | 0.02 | 2.70 | 0.22 | 1.43 | 0.24 | 1.65 |

| 24 September 2014 | −17.26 | −2.95 | 0.24 | 0.77 | −0.18 | −1.06 | −0.19 | −1.12 | |

| Fixed Line Telecommunications | 11 July 2006 | −20.93 | −3.56 | 0.07 | 1.73 | −0.22 | −1.98 | −0.22 | −2.04 |

| 19 February 2018 | 11.84 | 3.65 | 0.02 | 2.59 | 0.23 | 2.90 | 0.22 | 2.83 | |

| Sector | Intercept | t-Stat | Beta | t-Stat | Change in Beta | t-Stat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aerospace and Defense | 0 | −1.29 | 0.84 | 57.28 | 0.26 | 0.74 |

| Alternative Energy | 0 | −0.43 | 0.68 | 11 | −0.16 | 0.00 |

| Automobiles and Parts | 0 | −1.59 | 0.89 | 79.63 | −0.25 | −0.22 |

| Banks | 0 | −3.92 | 0.88 | 195.88 | 0.05 | 0.09 |

| Beverages | 0 | 0.43 | 0.93 | 49.37 | −0.27 | −0.25 |

| Chemicals | 0 | −0.38 | 0.87 | 79.12 | 0.27 | 0.29 |

| Construction and Materials | 0 | −0.24 | 0.82 | 49.39 | 0.18 | 0.16 |

| Electrical Equipment and Services | 0 | −1.71 | 0.85 | 97.68 | −0.1 | −0.09 |

| Electricity | 0 | 0.04 | −0.55 | −33.41 | 5.04 | 0.68 |

| Financial Services | 0 | −0.21 | 0.78 | 62.57 | 0.22 | 0.21 |

| Food and Drugs Retailers | 0 | −0.01 | 0.81 | 41.77 | 0.09 | 0.05 |

| Food Producers | 0 | −3.29 | 0.96 | 127.65 | 0.00 | −0.01 |

| Forestry and Papers | 0 | −1.44 | 0.9 | 60.39 | −0.23 | −0.14 |

| Gas, Water and Multiutilities | 0 | −1.71 | 0.98 | 125.04 | −0.02 | −0.04 |

| General Industrials | 0 | 0.27 | 0.96 | 105.16 | 0.23 | 0.12 |

| General Retailers | 0 | −2.79 | 0.94 | 122.29 | −0.15 | −0.12 |

| Healthcare Equipment and Services | 0 | −1.16 | 0.95 | 97.7 | −0.16 | −0.30 |

| Household Goods and Home Construction | 0 | −2.62 | 0.93 | 80.15 | −0.22 | −0.26 |

| Industrial Engineering | 0 | −4.44 | 0.95 | 160.08 | −0.07 | −0.20 |

| Industrial Metals and Mining | 0 | −2.55 | 0.94 | 94.28 | −0.78 | −0.69 |

| Industrial Transportation | 0 | −3.78 | 0.96 | 118.96 | 0.11 | 0.13 |

| Leisure Goods | 0 | −2.78 | 0.95 | 60 | −0.24 | −0.07 |

| Life Insurance | 0 | −0.4 | 0.93 | 128.09 | −0.16 | −1.43 |

| Media | 0 | −3.77 | 0.95 | 63.18 | −2.2 | −2.77 |

| Mining | 0 | −3.1 | 0.96 | 63.99 | −0.07 | −0.02 |

| Mobile Telecommunication | 0 | −0.01 | 0.98 | 165.98 | −0.27 | −1.54 |

| Nonlife Insurance | 0 | 0.98 | 0.87 | 71.36 | 0.10 | 0.07 |

| Oil Equipment | 0 | −2.48 | 0.97 | 129.17 | −0.06 | −0.07 |

| Oil and Gas Producers | 0 | −6.98 | 1.1 | 109.81 | −0.19 | −0.08 |

| Personal Goods | 0 | −3.22 | 0.95 | 85.55 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Pharmaceuticals and Biotechnology | 0 | −1.33 | 0.9 | 63.6 | 2.94 | 25.7 |

| Real Estate Investment Services | 0 | −2.47 | 0.98 | 205.83 | −0.19 | −0.41 |

| Real Estate Investment Trust | 0 | 0.84 | 0.98 | 212.35 | −0.03 | −0.12 |

| Software | 0 | −3.97 | 0.98 | 68.48 | 0.44 | 0.28 |

| Support Services | 0 | −1.17 | 0.91 | 42.04 | 0.21 | 0.07 |

| Technology Hardware and Equipment | 0 | −3.92 | 0.95 | 99.12 | 0.12 | 0.16 |

| Fixed Line Telecommunications | 0 | −1.6 | 0.94 | 66.93 | 0.22 | 0.21 |

| Travel and Leisure | 0 | −1.44 | 0.94 | 129.93 | −0.01 | −0.02 |

| Unclassified | 0 | −3.11 | 0.98 | 77.91 | −0.14 | −0.09 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pham, H.; Nguyen, V.; Ramiah, V.; Mudalige, P.; Moosa, I. The Effects of Environmental Regulation on the Singapore Stock Market. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2019, 12, 175. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm12040175

Pham H, Nguyen V, Ramiah V, Mudalige P, Moosa I. The Effects of Environmental Regulation on the Singapore Stock Market. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2019; 12(4):175. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm12040175

Chicago/Turabian StylePham, Huy, Van Nguyen, Vikash Ramiah, Priyantha Mudalige, and Imad Moosa. 2019. "The Effects of Environmental Regulation on the Singapore Stock Market" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 12, no. 4: 175. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm12040175

APA StylePham, H., Nguyen, V., Ramiah, V., Mudalige, P., & Moosa, I. (2019). The Effects of Environmental Regulation on the Singapore Stock Market. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 12(4), 175. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm12040175