Core Values at Work—Essential Elements of a Healthy Workplace

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. A Global Exploration—ICOH Special Sessions

3.2. Core Values and the Individual

3.3. Core Values Supported within Organizations and OSH

4. Discussion

4.1. Core Values and the Individual

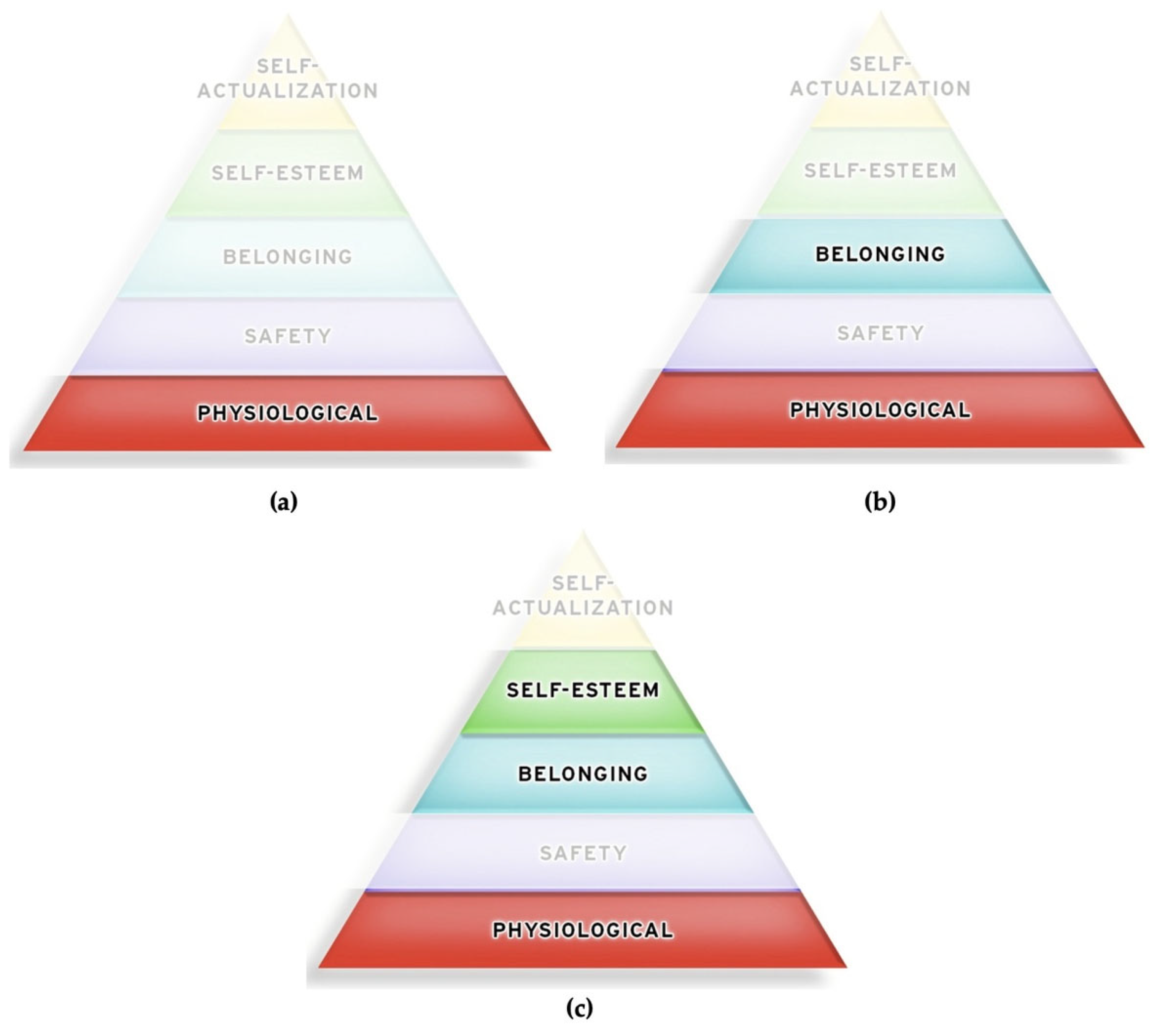

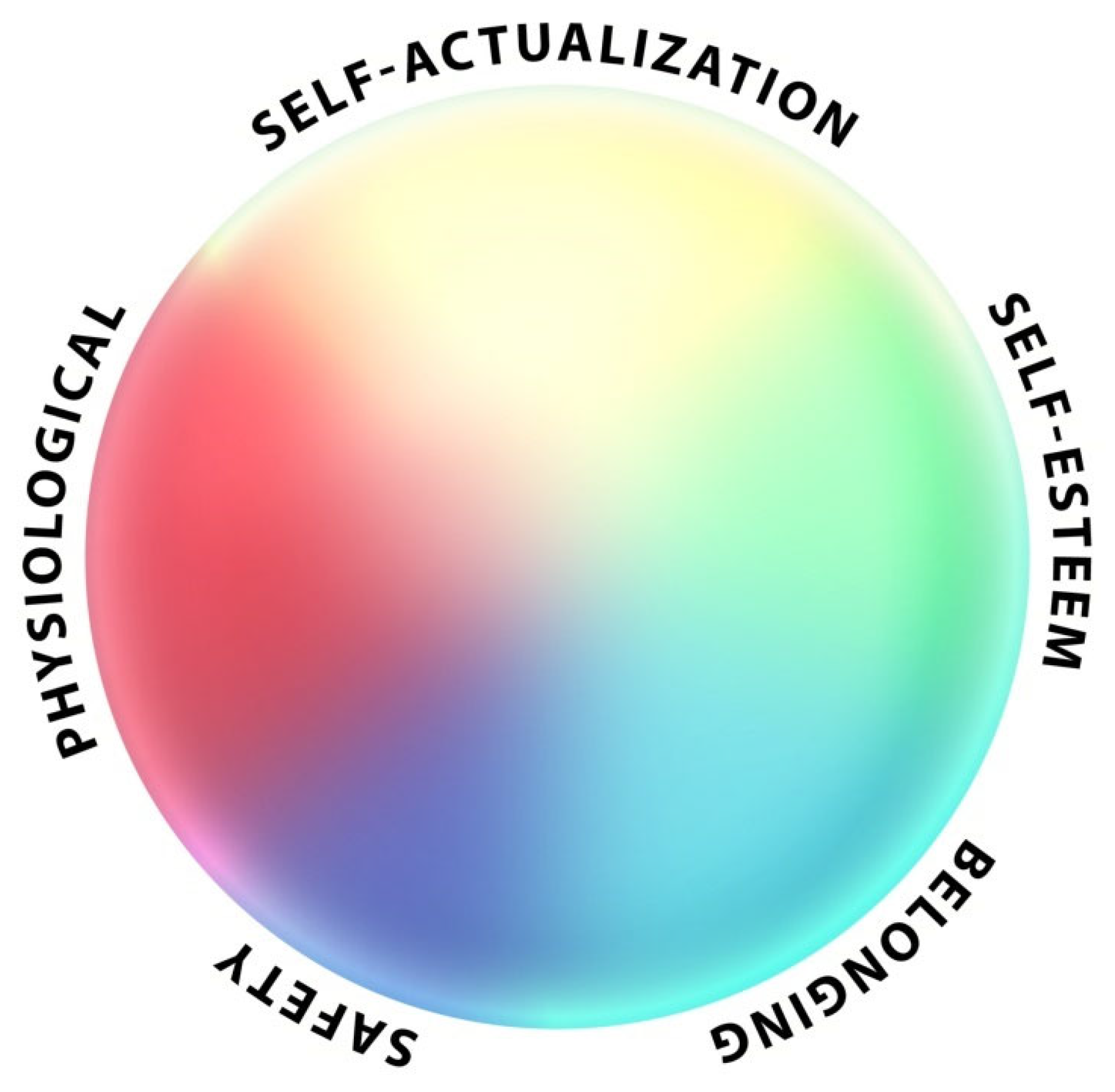

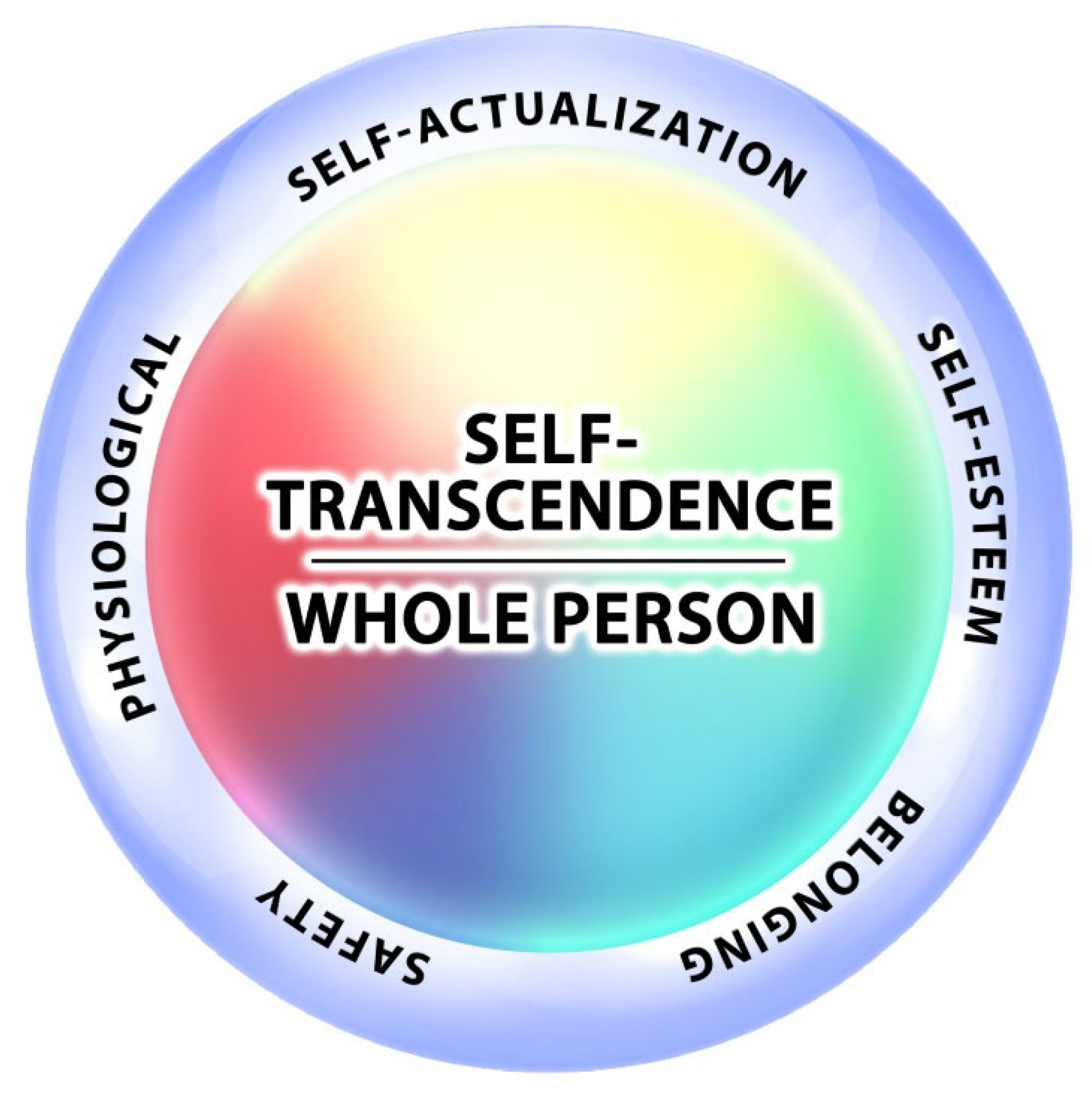

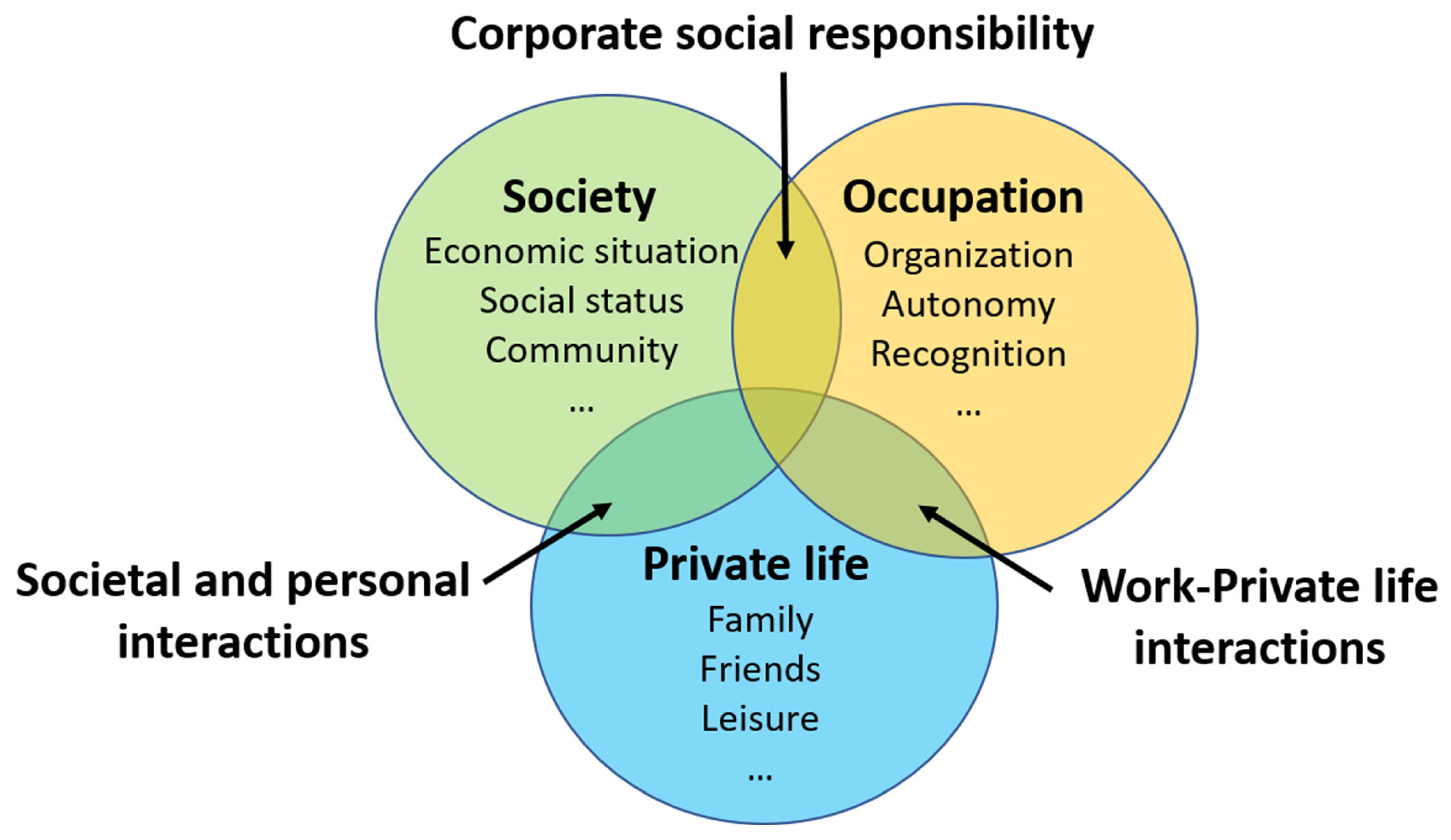

4.1.1. The Whole Person and Well-Being

4.1.2. The Psychology and Emotions of Work

4.1.3. Work Culture and Community

4.1.4. Meaningful Work

4.1.5. New Approaches in Leadership

4.1.6. Tools and Solutions for Supporting Core Values

4.2. Core Values Supported within Organizations and OSH

4.2.1. Meaning of Work in a Changing Environment

4.2.2. Global Perspective

- The WHO framework Healthy Workplace has at its center Ethics and Values which explicitly underlines their core importance [3].

- PAHO promotes health through the core value of kindness [52].

- Within ISSA, the Vision Zero program integrates the three dimensions of safety, health, and well-being at all levels of work [25]. Focused mainly on the technical and organizational aspects of health and safety, it is based on a vision, an ideal state, that will never be reached but can provide a clear direction for promoting values such as trust, transparency, fair leadership, commitment, and collaboration.

- The Total Worker Health™ program seeks to improve the well-being of U.S. workers by protecting their safety and enhancing their health, well-being, and productivity [26]. It recognizes that work acts as a social determinant of health and supports the importance of values.

4.2.3. Academic Research Perspectives and Salutogenesis

4.2.4. Challenges, Pitfalls, and Possible Solutions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guillemin, M.; Nicholas, R. Core Values at Work. First Newsletter of the Working Group; ICOH, SCETOH, Working Group Core Values at Work, 2021. Available online: http://www.robinnicholas.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Core-Values-at-Work-First-Newsletter-April-2021.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2022).

- Rose, F. Don’t mess with my sacred values. New York Times, 16 November 2013. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2013/11/17/opinion/sunday/dont-mess-with-my-sacred-values.html(accessed on 3 July 2022).

- Burton, J. WHO Healthy Workplace Framework and Model: Background and Supporting Literature and Practices; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/113144 (accessed on 3 July 2022).

- Guillemin, M. The New Dimensions of Occupational Health. Health 2019, 11, 592–607. Available online: https://www.scirp.org/journal/paperinformation.aspx?paperid=92835 (accessed on 3 July 2022). [CrossRef]

- Lum, M.; Guillemin, M.; Kortum, E.; Chosewood, L.C.; Anger, K.; Roquelaure, Y.; Nicholas, R. Work and spirituality: Summary report of a special session at the ICOH 31st International Congress in Seoul Korea. ICOH Newsl. 2016, 14, 4–20. Available online: http://www.icohweb.org/site/pdf-viewer/viewer.asp?newsletter=icoh_newsletter_vol14_no3.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2022).

- Van Dijk, F.; Guillemin, M.; Paris, C.; Zungu, M.; de Boer, A.; Mittal, A.; Kortum, E.; Nicholas, R. Work and spirituality: New approaches and ideas; Summary report of a special session at the ICOH 32nd International Congress in Dublin, Ireland. ICOH Newsl. 2018, 16, 12–16. Available online: http://www.icohweb.org/site/pdf-viewer/viewer.asp?newsletter=icoh_newsletter_vol16_no3.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2022).

- Van Dijk, F.; Guillemin, M.; Mittal, A.; Nicholas, R.; Seneviratne, M. Core values at work: Summary report of a workshop at the International Conclave on Occupational Health in Mumbai, India. ICOH Newsl. 2020, 18, 15–17. Available online: http://www.icohweb.org/site/pdf-viewer/viewer.asp?newsletter=icoh_newsletter_vol18_no2.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2022).

- Räsänen, T.; Anttonen, H. Definition of Wellbeing at Work and the Various Categories for Evaluation of Work Activities. Presented at the Towards Better Work and Wellbeing, Helsinki, Finland. 10–12 February 2010. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/45010167(accessed on 3 July 2022).

- Schulte, P.; Vainio, H. Wellbeing at work: Overview and perspective. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2010, 6, 422–429. Available online: https://www.sjweh.fi/article/3076 (accessed on 3 July 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waddell, G.; Burton, A.K. Is Work Good for Your Health and Wellbeing? The Stationary Office (TSO): London, UK, 2006; Available online: http://www.mas.org.uk/uploads/artlib/is-work-good-for-your-health-and-well-being.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2022).

- Wright, T.A.; Cropanzano, R. Psychological well-being and job satisfaction as predictors of job performance. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2000, 5, 84–94. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/12655756_Psychological_well-being_and_job_satisfaction_as_predictors_of_job_performance (accessed on 3 July 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindström, B. Salutogenesis. An Introduction; Folkhälsan Research Center, Health Promotion Research: Helsinki, Finland, 2010; Available online: http://www.centrelearoback.org/assets/PDF/04_activites/clr-GCPB121122-Lindstom_pub_introsalutogenesis.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2022).

- Damasio, A.R. Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain; Avon Books: New York, NY, USA, 1994; Available online: https://ahandfulofleaves.files.wordpress.com/2013/07/descartes-error_antonio-damasio.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2022).

- Maslow, A.H. A theory of human motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1943, 50, 370–396. Available online: http://psychclassics.yorku.ca/Maslow/motivation.htm (accessed on 3 July 2022). [CrossRef]

- Wrzesniewski, A.; Schwartz, B.; Xiangyu, C.; Kane, M.; Omar, A.; Kolditz, T. Multiple types of motives don’t multiply the motivations of West Point cadets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 10990–10995. Available online: https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1405298111 (accessed on 3 July 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, J.; Edwards, L. Do you know what kind of commitment they have. In Managing Talent Retention; Phillips, J., Edwards, L., Eds.; Pfeiffer: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2009; Available online: https://www.enterpriseengagement.org/Do-You-Know-What-Kind-of-Commitment-They-Have/ (accessed on 3 July 2022).

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity: The General Conference, 31st Session, 2 November 2001. Available online: https://adsdatabase.ohchr.org/IssueLibrary/UNESCO%20Universal%20Declaration%20on%20Cultural%20Diversity.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2022).

- Mkhize, N. A primer: Doing research in traditional cultures. Protect. Hum. Subj. 2005, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Bryce, A. Finding Meaning Through Work: Eudaimonic Well-Being and Job Type in the US and UK; Sheffield Economic Research Paper Series (SERPS) 2018004; University of Sheffield, Department of Economics: Sheffield, UK, 2018; Available online: http://www.sheffield.ac.uk/economics/research/serps/articles/2018004 (accessed on 3 July 2022).

- YPAI 2020 International. Young Professional Attraction Index (YPAI); Survey; Academic Work: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: https://www.academicwork.ch/business/ypai-2020-international#:~:text=YPAI%202020%20International%20%E2%80%93%20Attracting%20young,the%20European%20talents%20of%20tomorrow (accessed on 3 July 2022).

- Barrett, R. Liberating the Corporate Soul: Building a Visionary Organization; Routledge: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Laloux, F. Reinventing Organizations: A Guide to Creating Organizations Inspired by the Next Stage of Human Consciousness; Nelson Parker: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Reicher, S.D.; Platow, M.J.; Haslam, A. The new psychology of leadership. Sci. Am. Mind 2007, 18, 22–29. Available online: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-new-psychology-of-leadership-2007-08/ (accessed on 3 July 2022). [CrossRef]

- Guillemin, M. New Avenues for Prevention of Work-Related Diseases Linked to Psychosocial Risks. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11354. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34769869/ (accessed on 3 July 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Social Security Association. Vision ZERO, 7 Golden Rules for Zero Accidents and Healthy Work: A Guide for Employers and Managers; ISSA: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; Available online: https://aaa.public.lu/dam-assets/fr/publication/guides/7-regles-dor-de-la-vision-zero/en-vision-zero-guide-web.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2022).

- Hudson, H.L.; Nigam, J.A.S.; Sauter, S.L.; Chosewood, L.C.; Schill, A.L.; Howard, J. (Eds.) Total Worker Health™; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lesley University Blog. The Power of Company Core Values; Lesley University: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; Available online: https://lesley.edu/article/the-power-of-company-core-values (accessed on 3 July 2022).

- International Commission on Occupational Health (ICOH). ICOH International Code of Ethics for Occupational Health Professionals, 3rd ed.; International Commission on Occupational Health: Rome, Italy, 2014; pp. 1–30. Available online: http://www.icohweb.org/site/code-of-ethics.asp (accessed on 3 July 2022).

- Howard, C.A. Health Safety & Wellbeing at Work: A Review of the Literature; Academia.edu: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2018; Available online: https://www.academia.edu/40475793/Health_Safety_and_Wellbeing_at_Work_A_review_of_the_literature (accessed on 3 July 2022).

- Zwetsloot, G.I.J.M.; van Scheppingen, A.R.; Bos, E.H.; Dijkman, A.; Starren, A. The core values that support health, safety, and well-being at work. Saf. Health Work 2013, 4, 187–196. Available online: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2093791113000425 (accessed on 3 July 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palazzo, G.; Krings, F.; Hoffrage, U. Ethical blindness. J Bus Ethics 2012, 109, 323–338. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/256046104_Ethical_Blindness (accessed on 3 July 2022).

- Tourish, D. The Dark Side of Transformational Leadership: A Critical Perspective; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014; Available online: https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203558119 (accessed on 3 July 2022). [CrossRef]

- ISO 26000; Social Responsibility. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland. Available online: https://www.iso.org/iso-26000-social-responsibility.html(accessed on 3 July 2022).

- Monroe, J. History of the Four Way Test; Rotary Blog; Rotary Club of Lake Stevens: Lake Stevens, WA, USA; Available online: https://portal.clubrunner.ca/274/stories/history-of-the-four-way-test (accessed on 3 July 2022).

- Nicholas, R. Worker values, Culture, and Community: Values Communication that Goes Directly to Workers and Supports Wellbeing. In Proceedings of the Towards Better Work and Well-being, Finnish Institute of Occupational Health, Helsinki, Finland, 10–12 February 2010; Available online: http://www.robinnicholas.com/index.php/worker-values-culture-and-community/ (accessed on 3 July 2022).

- Agassi, J.B. (Ed.); Martin Buber on Psychology and Psychotherapy: Essays, Letters, and Dialogue; Syracuse University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999; Available online: https://press.syr.edu/supressbooks/1377/martin-buber-on-psychology-and-psychotherapy/ (accessed on 3 July 2022).

- Nicholas, R. Beyond the intellect: Communicating Core Values to Support Worker Wellbeing. Presented at Wellbeing at Work, Copenhagen, Denmark. 26–28 May 2014. Available online: http://www.robinnicholas.com/index.php/beyond-the-intellect-communicating-core-values-to-support-worker-wellbeing/(accessed on 3 July 2022).

- Nicholas, R. Management, Culture and Community: Creating an Environment of Well-Being. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Accident Prevention (ICAP), Korean Occupational Safety and Health Agency, Busan, Korea, 20–22 October 2010; Available online: http://www.robinnicholas.com/index.php/114-2/ (accessed on 3 July 2022).

- Bridgman, T.; Cummings, S.; Ballard, J. Who built Maslow’s Pyramid? A history of the creation of management studies’ most famous symbol and its implications for management education. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2019, 18, 81–98. Available online: https://journals.aom.org/doi/10.5465/amle.2017.0351 (accessed on 3 July 2022). [CrossRef]

- Nicholas, R. The Experience of Work. Presented at ICOH Conference, Dublin, Ireland, 29 April–4 May 2018; Video Excerpt. Available online: http://www.robinnicholas.com/index.php/work-culture/(accessed on 3 July 2022).

- Maslow, A.H. The Farther Reaches of Human Nature; Arkana-Penguin Books: New York, NY, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas, R. Work Culture and Values: A Summary. 2021. Available online: http://www.robinnicholas.com/index.php/work-culture-and-values-a-summary (accessed on 3 July 2022).

- Mulligan, M.; Humphery, K.; James, P.; Stanlon, C.; Smith, P.; Welch, N. Creating Community: Celebrations, Arts, and Well-Being within and across Local Communities; VicHealth and The Globalism Institute, RMIT University: Melbourne, Australia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Story, J.; Castanheira, F.; Hartig, S. Corporate social responsibility and organizational attractiveness: Implications for talent management. Soc. Responsib. J. 2016, 12, 484–505. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1108/SRJ-07-2015-0095 (accessed on 3 July 2022). [CrossRef]

- Ferrie, J.E. (Ed.) Work, Stress, and Health: The Whitehall II Study; Council of Civil Service Unions-Cabinet Office: London, UK, 2004. Available online: https://reflexus.org/wp-content/uploads/wii-booklet.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2022).

- Hougaard, R.; Carter, J. The Mind of the Leader: How to Lead Yourself, Your People, and Your Organization for Extraordinary Results; HBR Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 1–50. Available online: https://fliphtml5.com/cflig/mkcv/basic (accessed on 3 July 2022).

- Bennett, G.; Jessani, N. (Eds.) The Knowledge Translation Toolkit. Bridging the Know-Do Gap: A Resource for Researchers; Sage Publications: New Delhi, India, 2011; Available online: https://idl-bnc-idrc.dspacedirect.org/bitstream/handle/10625/46152/IDL-46152.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 3 July 2022).

- Littlebird, L. Be Quiet, Sit Down and Listen: A Native American Sound Quest; NHK–Japan Broadcasting Corporation: Tokyo, Japan, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Nadarajah, Y. Communities in Transition: Propagating a Yield of Violence. In De-Naturalising Violence: Trans-Disciplinary Explorations; Cervantes-Carson, A., Cromer, G., Eds.; Inter-Disciplinary Press: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ka’ano’i, P. The Need for Hawaii: A Guide to Hawaiian Cultural and Kahuna Values; Ka’ano’i Productions: Henderson, NV, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Rantanen, R. Solidarity: A key ICOH objective. ICOH Newsl. 2007, 5, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Pan American Health Organization. Kindness in the Workplace Survey: Survey to Evaluate the Implementation of the Initiative “Make Kindness Contagious!”; PAHO-WHO: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; Available online: https://www.paho.org/en/node/50347 (accessed on 3 July 2022).

- Stratil, J.M.; Rieger, M.A.; Völter-Mahlknecht, S. Cooperation between general practitioners, occupational health physicians, and rehabilitation physicians in Germany: What are problems and barriers to cooperation? A qualitative study. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2017, 90, 481–490. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28285323/ (accessed on 3 July 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Bettignies, H.C.; Lépineux, F. (Eds.) Finance for a Better World: The Shift Towards Sustainability; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Marnet, O. Behaviour and Rationality in Corporate Governance. Int. J. Behav. Acc. Financ. 2008, 1, 4–22. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/46513946_Behaviour_and_Rationality_in_Corporate_Governance (accessed on 3 July 2022). [CrossRef]

- Antonovsky, A. Salutogenesis; Studying Health vs. Studying Disease. Presented at the Congress for Clinical Psychology and Pschotherapy, Berlin, Germany. 19 February 1990, p. 9. Available online: https://www.angelfire.com/ok/soc/aberlim.html (accessed on 3 July 2022).

- Aichner, T.; Coletti, P.; Jacob, F.; Wilken, R. Did the Volkswagen Emissions Scandal Harm the “Made in Germany” Image? A Cross-Cultural, Cross-Products, Cross-Time Study. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2021, 24, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, R.G. Human Rights Really Aren’t All That Important: Just Ask 200 Leading Companies; Forbes: New York, NY, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/bobeccles/2020/03/09/human-rights-really-arent-all-that-important-just-ask-200-leading-companies/?sh=4de6bd0f6e51 (accessed on 3 July 2022).

- Jesep, P.P. Lost Sense of Self & the Ethics Crisis: Learn to Live and Work Ethically; Paperback; Createspace Independent Publishing Platform: Scotts Valley, CA, USA, 2012; Available online: https://www.bookpeople.com/book/9781479238309 (accessed on 3 July 2022).

| International Conference | Special Session Workshop | Chairpersons | Location Country | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICOH 31st—2015 | Work and Spirituality | Max Lum | Seoul, South Korea | [5] |

| ICOH 32nd—2018 | Work and Spirituality | Frank van Dijk Christophe Paris | Dublin, Ireland | [6] |

| Int. Conclave on OH 2020 | Core Values at Work | Frank van Dijk | Mumbai, India | [7] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guillemin, M.; Nicholas, R. Core Values at Work—Essential Elements of a Healthy Workplace. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12505. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912505

Guillemin M, Nicholas R. Core Values at Work—Essential Elements of a Healthy Workplace. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(19):12505. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912505

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuillemin, Michel, and Robin Nicholas. 2022. "Core Values at Work—Essential Elements of a Healthy Workplace" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 19: 12505. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912505

APA StyleGuillemin, M., & Nicholas, R. (2022). Core Values at Work—Essential Elements of a Healthy Workplace. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 12505. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912505