The Effect of Subjective Exercise Experience on Exercise Behavior and Amount of Exercise in Children and Adolescents: The Mediating Effect of Exercise Commitment

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Participants and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measuring Tools

2.2.1. Subjective Exercise Experience Scale (SEES)

2.2.2. Exercise Commitment Checklist (ECC)

2.2.3. Physical Activity Rating Scale (PARS-3)

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Common Method Bias Test

3.2. Demographic Differences in Primary Variables

3.3. Correlations among Children and Adolescents’ Subjective Exercise Experience, Exercise Commitment, and Exercise Behavior

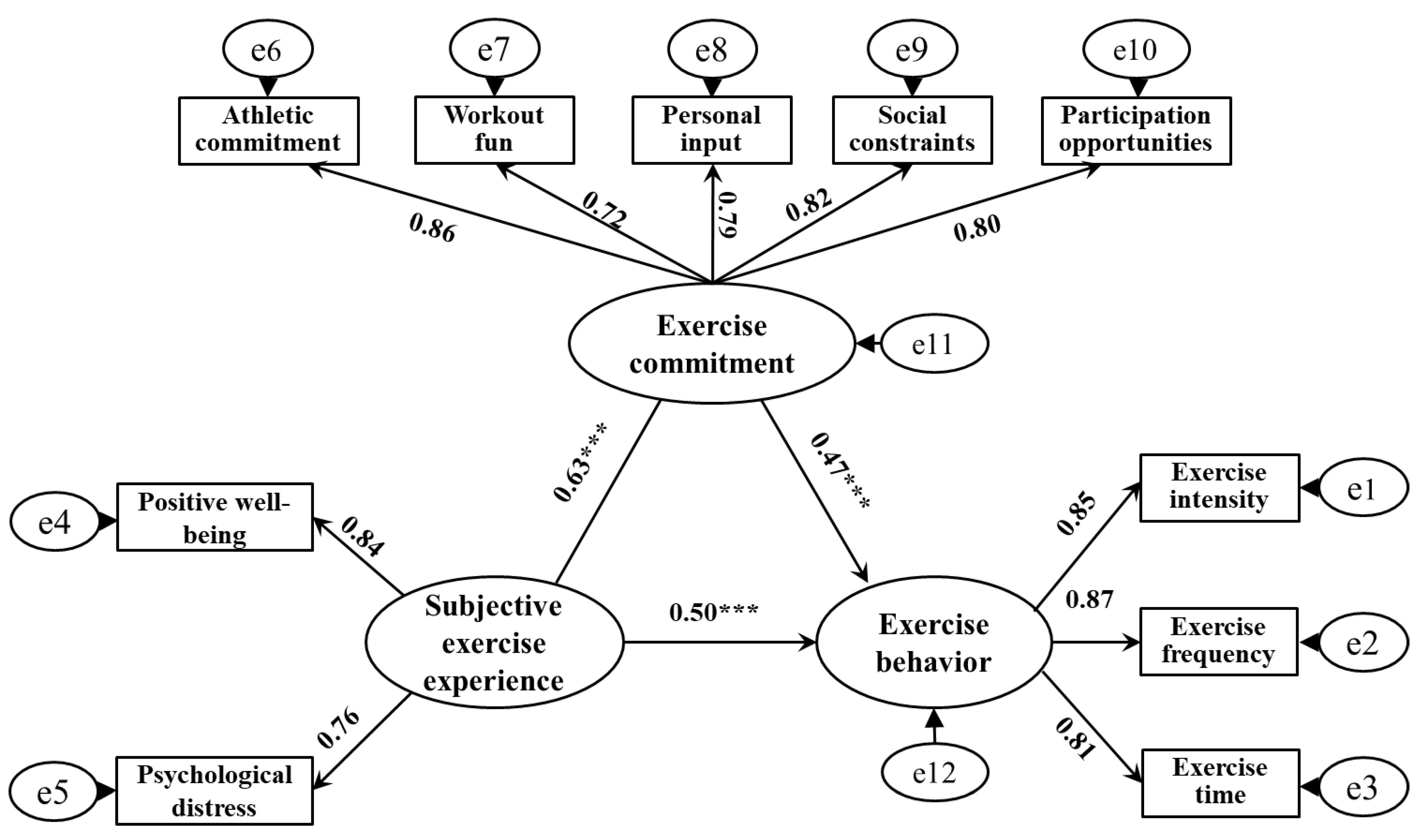

3.4. The Effect and Path Relationship of Subjective Exercise Experience on Exercise Behavior

3.4.1. The Direct Effect Analysis

3.4.2. Analysis of Mediation Effect

4. Discussion

4.1. Demographic Difference Analysis

4.2. The Direct Effect of Subjective Exercise Experience on Exercise Behavior

4.3. The Mediating Effect of Exercise Commitment between Subjective Exercise Experience and Exercise Behavior

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhou, S.X. Pay Attention to Sports and Start from These Aspects. Guangming Daily, 21 November 2019. Available online: http://news.cctv.com/2019/11/21/ARTIRzpi3FH5WBbzqhXFKyh8191121.shtml (accessed on 21 May 2022).

- Zhou, L.Y.; Xu, L. Interpretation and thinking of “change tendency” of the physical quality and health status of Chinese students. J. Guangzhou Sport Univ. 2013, 33, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.T. Teenagers “Physical Lag”: Sociological attribution and collaborative governance. J. Guangzhou Sport Univ. 2019, 39, 35–40, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Ma, X.L. The relationship between physical exercise and mental health of Kazakh middle school students in Tacheng boarding. Chin. J. Sch. Health 2017, 38, 932–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, S.B.; Dring, K.J.; Morris, J.G.; Sunderland, C.; Bandelow, S.; Nevill, M.E. High intensity intermittent games-based activity and adolescents’ cognition: Moderating effect of physical fitness. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Li, Q.; Zhang, Z.K.; Wang, B.Y.; Zhu, F.S. The influence of extracurricular physical exercise on the physical self-esteem and self-confidence of elementary students. J. Sports Sci. 2019, 40, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairclough, S.J.; Tyler, R.; Dainty, J.R.; Dumuid, D.; Richardson, C.; Shepstone, L.; Atkin, A.J. Cross-sectional associations between 24-hour activity behaviours and mental health indicators in children and adolescents: A compositional data analysis. J. Sports Sci. 2021, 39, 1602–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, J.; Pellicer-Chenoll, M.; Garcia-Masso, X.; Gomez, A.; Gomis, M.; Gonzalez, L.M. Relation between physical activity and academic performance in 3rd-year secondary education students. Percept. Mot. Ski. 2011, 29, 539–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishihara, T.; Sugasawa, S.; Mstsuda, Y.; Mizuno, M. The beneficial effects of game-based exercise using age-appropriate tennis lessons on the executive functions of 6~12-year-old children. Neurosci. Lett. 2017, 642, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.Y.; Liu, D.S.; Feng, F.H.; Li, R. Epidemiologic study on relationship between physical activity, physical fitness and obesity risks in children and adolescents. J. Wuhan Inst. Phys. Educ. 2015, 49, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carron, A.V. Cohesiveness in sport groups: Implications and considerations. J. Sport Psychol. 1982, 4, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, S.M.; Carron, A.V.; Eys, M.A.; Ntoumanis, N.; Estabrooks, P.A. Group versus individual approach? A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of interventions to promote physical activity. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2006, 2, 19–35. [Google Scholar]

- Yuen, H.K.; Wang, E.; Holthaus, K.; Vogtle, L.K.; Sword, D.; Breland, H.L.; Kamen, D.L. Self-reported versus objectively assessed exercise adherence. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2013, 67, 484–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, B.L. Investigation and analysis of the influence of health belief and social support on teenager physical exercise. J. Phys. Educ. 2017, 24, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.H.; Zhang, J.C.; Jin, Y.H.; Li, N.H. Study on physical exercise adherence in foreign countries. J. Shanghai Phys. Educ. Inst. 2002, 26, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social learning theory. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2000, 1, 33–52. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.M.; Liu, X. Truth, Alienation and regression of teenager students’ sports behaviors. J. Beijing Sport Univ. 2017, 40, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sealey, R.M. Acute Exercise in Vietnam Veterans is Associated with Positive Subjective Experiences. Int. J. Exerc. Sci. 2010, 3, 36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.E.; Du, F.Q. Relations between Subjective Exercise Experience and Physical Health of Middle School Students. J. Tianjin Univ. Sport 2010, 25, 228–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.F.; Zhou, L.; Li, X.D. The relationship of physical self—esteem, goal orientation and exercise experience. J. Shandong Inst. Phys. Educ. Sports 2008, 24, 57–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.P.; Li, S.Z.; Yan, Z.L. Research on Mechanism of Exercise Persistence Based on Sport Commitment Theory. China Sport Sci. 2006, 26, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.H.; Jiang, C.H. Theory models of emotional memory. J. Northwest Norm. Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2008, 45, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.N.; Ji, L.; Watson Jack, C., II. Research Advancement of Flow State in the Field of Sport. China Sport Sci. 2009, 29, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astin, A.W. Student involvement: A developmental theory for higher education. J. Coll. Stud. Pers. 1984, 25, 297–308. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Human agency in social cognitive theory. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 1175–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Chen, S.P.; Pan, H.S. Psychological decision-making in exercise persistence. J. Shenyang Sport Univ. 2010, 29, 72–75. [Google Scholar]

- Scanlan, T.; Carpenter, P.; Schmidt, G.; Simons, J.P.; Keeler, B. An introduction to the sport commitment model. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 1993, 15, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.P.; Pan, X.G.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, Z.J. On the designation reliability and validity of exercise effects inventory (EEI) for Chinese college students. J. Beijing Sport Univ. 2018, 31, 1404–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, F.; Cui, D.G.; Yang, J. Influence factors of undergraduates’ exercise behavior based on sport commitment. J. Tianjin Univ. Sport 2011, 26, 384–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan, B.M.; Bryan, A. In-task and post-task affective response to exercise: Translating exercise intentions into behaviour. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2010, 15, 115–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahariadis, P.; Tsorbatzoudis, H.; Alexandris, K. Self-determination in sport commitment. Percept. Mot. Ski. 2006, 102, 405–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.Q.; Dong, B.L. Subjective experience, commitment and exercise adherence of undergraduates: A case study of androgyny and undifferentiation. J. Sports Res. 2016, 30, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, A.; Hutchison, K.E.; Seals, D.R.; Allen, D.L. A transdisciplinary model integrating genetic, physiological, and psychological correlates of voluntary exercise. Health Psychol. 2007, 26, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, D.M.; Dunsiger, S.; Ciccolo, J.T.; Lewis, B.A.; Albrecht, A.E.; Marcus, B.H. Acute affective response to a moderate- intensity exercise stimulus predicts physical activity participation 6 and 12 months later. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2008, 9, 231–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mcauley, E.; Courneya, K.S. The subjective exercise experiences scale (SEES): Development and preliminary evaluation. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 1994, 16, 163–177. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.P.; Li, S.Z. Research on the test of the sport commitment model under the sport participations among college students in China. J. Beijing Sport Univ. 2006, 29, 623–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, D.Q. Stress level and its relation with physical activity in higher education. Chin. Ment. Health J. 1994, 8, 5–6. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Mackenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Zhang, M.Q.; Qiu, H.Z. Mediation Analysis and Effect Size Measurement: Retrospect and Prospect. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2012, 28, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Process: A Versatile Computational Tool for Observed Variable Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Modeling. 2012. Available online: http://www.afhayes.com/public/process (accessed on 21 May 2022).

- Dong, B.L.; Mao, L.J. Influence of exercise involvement, exercise commitment and subjective experience on exercise habits of undergraduates: A mixed model. J. Tianjin Univ. Sport 2018, 33, 492–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, P.T.; Lindsay, L.L. Interparental conflict and adolescent adjustment: Why does gender moderate early adolescent vulnerability? J. Fam. Psychol. 2004, 18, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, B.L.; Zhang, H. Gender-roles, subjective exercise experience, sport commitment and exercise behavior of undergraduates: A model of chain mediating effect. J. Tianjin Univ. Sport 2016, 31, 414–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.Y.; Mao, Z.X.; Guo, L. Development of psychological decision-making model of exercise adherence: The value added contribution of positive affective experience. J. Tianjin Univ. Sport 2016, 31, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jekauc, D. Enjoyment during exercise mediates the effects of an intervention on exercise adherence. Psychology 2015, 6, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakoff, G.; Johnson, M. The metaphorical structure of the human conceptual system. Cogn. Sci. A Multidiscip. J. 1980, 4, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.S. In two minds: Dual-process accounts of reasoning. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2003, 7, 454–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, P.M.; Rodgers, W.M.; Carpenter, P.J. The relationship between commitment and exercise behavior. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2004, 5, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, P.J.; Coleman, R. A longitudinal study of elite youth cricketers’ commitment. Int. J. Sport Psychol. 1998, 29, 195–210. [Google Scholar]

- Ekkekakis, P. Pleasure and displeasure from the body: Perspectives from exercise. Cogn. Emot. 2003, 17, 213–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Scale | KMO and Bartlett Spherical Test | Dimension | Items | Characteristic Root | Variance Explained (%) | Cumulative Explained Variance(%) | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SEES | KMO = 0.90 (p < 0.001) | Positive well-being | 4 | 3.26 | 35.17 | 35.17 | 0.85 |

| Psychological distress | 4 | 1.89 | 16.20 | 51.37 | 0.82 | ||

| ECC | KMO = 0.87 (p < 0.001) | Exercise commitment | 3 | 6.83 | 24.25 | 24.25 | 0.86 |

| Exercise fun | 3 | 4.90 | 15.18 | 39.43 | 0.78 | ||

| Personal investment | 3 | 3.55 | 9.33 | 48.76 | 0.80 | ||

| Social constraints | 3 | 1.83 | 6.76 | 55.52 | 0.83 | ||

| Participation opportunities | 3 | 1.12 | 4.19 | 59.71 | 0.80 | ||

| PARS-3 | KMO = 0.85 (p < 0.001) | Amount of physical activity | 3 | 4.03 | 54.26 | 54.26 | 0.82 |

| Category | Variable | Subjective Exercise Experience | Exercise Commitment | Exercise Behavior |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | boys | 27.89 ± 4.41 | 49.97 ± 9.03 | 29.56 ± 6.80 |

| girls | 28.73 ± 5.37 | 45.08 ± 8.12 | 25.33 ± 5.39 | |

| t | 1.52 | 3.55 * | 3.37 * | |

| Age | 9–12 | 28.57 ± 5.38 | 48.37 ± 8.11 | 29.18 ± 6.21 |

| 13–15 | 28.11 ± 5.09 | 46.62 ± 7.19 | 25.71 ± 5.57 | |

| t | 0.87 | 2.45 | 3.21 * |

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjective exercise experience (1) | 28.31 | 4.89 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Exercise commitment (2) | 47.52 | 8.58 | 0.63 *** | ||

| Exercise behavior (3) | 27.45 | 6.10 | 0.57 *** | 0.52 *** |

| Variable | Exercise Commitment | Exercise Behavior | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | R2 | 95%CI | β | R2 | 95%CI | |

| Subjective exercise experience | 0.63 *** | 0.40 | (0.59, 0.67) | 0.57 *** | 0.32 | (0.51, 0.60) |

| Exercise commitment | 0.52 *** | 0.27 | (0.49, 0.58) | |||

| Effect Category | Standardized Effect Size | Ratio of Total Effect | Bootstrap SE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total effect | 0.80 | 100% | 0.01 |

| Direct effect | 0.50 | 62.50% | 0.02 |

| Indirect effect | 0.63 × 0.47 = 0.30 | 37.50% | 0.03 |

| Variable | Exercise Commitment | Low Exercise Amount | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t | β | 95%CI | t | β | 95%CI | |

| Subjective exercise experience Exercise commitment | 3.61 | 0.39 ** | (0.35, 0.41) | 3.27 2.14 | 0.33 ** 0.22 * | (0.25, 0.40) (0.16, 0.31) |

| R2 | 0.15 | 0.20 | ||||

| F | 4.20 ** | 5.18 ** | ||||

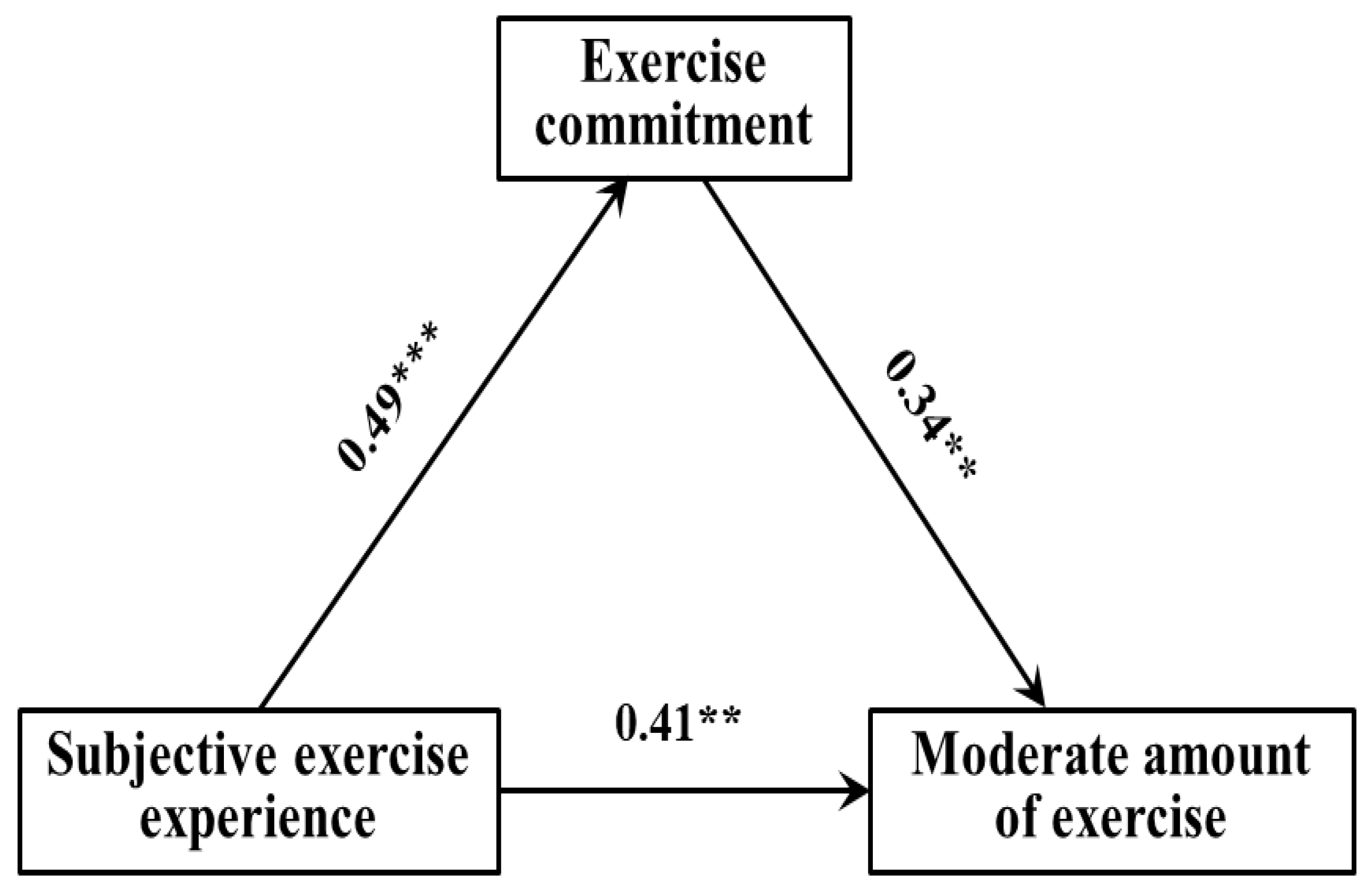

| Variable | Exercise Commitment | Moderate Exercise Amount | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t | β | 95%CI | t | β | 95%CI | |

| Subjective exercise experience Exercise commitment | 4.93 | 0.49 *** | (0.45, 0.62) | 3.30 4.25 | 0.34 ** 0.41 ** | (0.31, 0.39) (0.36, 0.47) |

| R2 | 0.24 | 0.28 | ||||

| F | 7.11 *** | 7.67 ** | ||||

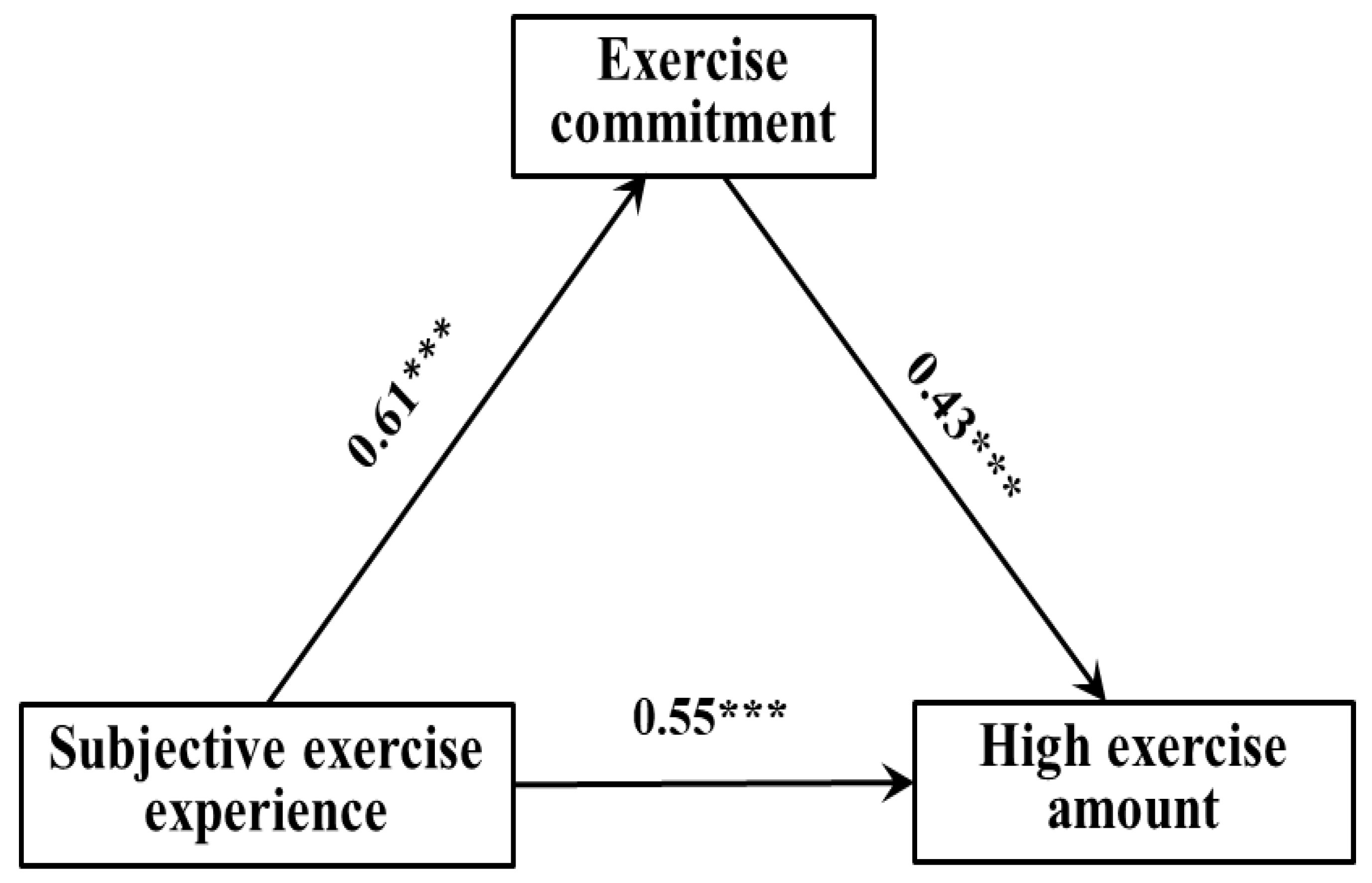

| Variable | Exercise Commitment | High Exercise Amount | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t | β | 95%CI | t | β | 95%CI | |

| Subjective exercise experience Exercise commitment | 6.25 | 0.61 *** | (0.52, 0.67) | 4.67 5.09 | 0.43 *** 0.55 *** | (0.38, 0.49) (0.51, 0.62) |

| R2 | 0.37 | 0.44 | ||||

| F | 9.58 *** | 10.13 *** | ||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

He, L.; Li, Y.; Chen, Z. The Effect of Subjective Exercise Experience on Exercise Behavior and Amount of Exercise in Children and Adolescents: The Mediating Effect of Exercise Commitment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10829. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710829

He L, Li Y, Chen Z. The Effect of Subjective Exercise Experience on Exercise Behavior and Amount of Exercise in Children and Adolescents: The Mediating Effect of Exercise Commitment. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(17):10829. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710829

Chicago/Turabian StyleHe, Linghui, Yan Li, and Zhenhuai Chen. 2022. "The Effect of Subjective Exercise Experience on Exercise Behavior and Amount of Exercise in Children and Adolescents: The Mediating Effect of Exercise Commitment" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 17: 10829. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710829

APA StyleHe, L., Li, Y., & Chen, Z. (2022). The Effect of Subjective Exercise Experience on Exercise Behavior and Amount of Exercise in Children and Adolescents: The Mediating Effect of Exercise Commitment. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(17), 10829. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710829