HIV-Associated Systemic Sclerosis: Literature Review and a Rare Case Report

Abstract

:1. Introduction

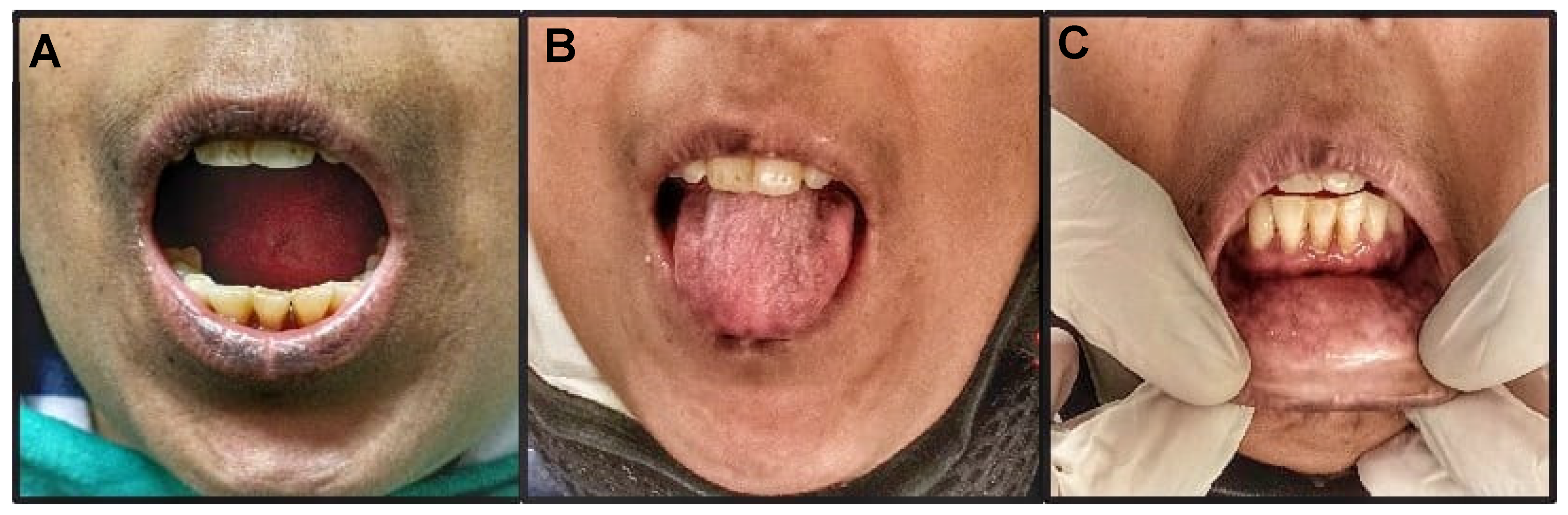

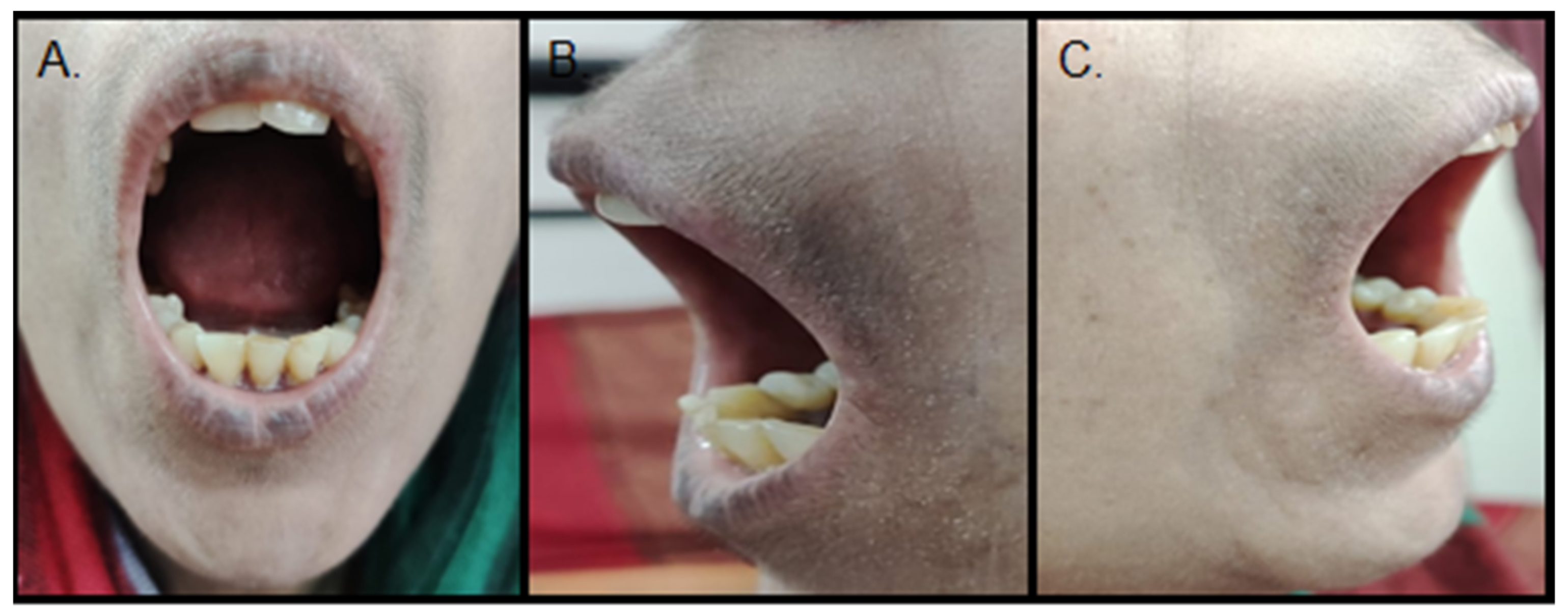

2. Case Report

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mubder, M.; Azab, M.; Jayaraj, M.; Cross, C.; Lankarani, D.; Dhindsa, B.; Pan, J.J.; Ohning, G. Autoimmune hepatitis in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection: A systematic review of the published literature. Medicine 2019, 98, e17094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okada, A.; Nozaki, Y.; Rai, S.; Kinoshita, K.; Funauchi, M.; Matsumura, I. Antiretroviral Therapy Improves Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Life 2021, 11, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iordache, L.; Launay, O.; Bouchaud, O.; Jeantils, V.; Goujard, C.; Boue, F.; Cacoub, P.; Hanslik, T.; Mahr, A.; Lambotte, O.; et al. Autoimmune diseases in HIV-infected patients: 52 cases and literature review. Autoimmun. Rev. 2014, 13, 850–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christoforidou, A.; Galanopoulos, N. Diffuse connective tissue disorders in HIV-infected patients. Mediterr. J. Rheumatol. 2018, 29, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okong’o, L.O.; Webb, K.; Scott, C. HIV-associated juvenile systemic sclerosis: A case report. Semin. Arthritis. Rheum. 2015, 44, 411–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maganti, R.M.; Reveille, J.D.; Williams, F.M. Therapy Insight: The Changing Spectrum of Rheumatic Disease in HIV Infection. Nat. Clin. Pract. Rheumatol. 2008, 4, 428–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergamasco, A.; Hartmann, N.; Wallace, L.; Verpillat, P. Epidemiology of systemic sclerosis and systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease. Clin Epidemiol. 2019, 11, 257–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, S.; Khan, R.; Harron, M.; Khwaja, K.; Tarranum, F.; Husain, A. Systemic sclerosis: Case report and literature review. Int. J. Contemp. Dent. 2011, 2, 46–53. [Google Scholar]

- Jagadish, R.; Mehta, D.S.; Jagadish, P. Oral and periodontal manifestations associated with systemic sclerosis: A case series and review. J. Indian Soc. Periodontol. 2012, 16, 271–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabongo, M.; Buch, B.; Hira, P.; Ngwenya, S. Progressive Systemic Sclerosis—An extensive manifestation of Scleroderma. S. Afr. Dent. J. 2015, 70, 156–158. [Google Scholar]

- Panchbhai, A.; Pawar, S.; Barad, A.; Kazi, Z. Review of orofacial considerations of systemic sclerosis or scleroderma with report of analysis of 3 cases. Indian J. Dent. 2016, 7, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bali, V.; Dabra, S.; Behl, A.B.; Bali, R. A rare case of hidebound disease with dental implications. Dent. Res. J. 2013, 10, 556–561. [Google Scholar]

- Jackowski, J.; Strietzel, F.P.; Hunzelmann, N.; Parwani, P.; Jackowski, A.; Benz, K. Dental implants in patients suffering from systemic sclerosis: A retrospective analysis of clinical outcomes in a case series with 24 patients. Int. J. Implant. Dent. 2021, 7, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puzio, A.; Przywara-Chowaniec, B.; Postek-Stefańska, L.; Mrówka-Kata, K.; Trzaska, k. Systemic sclerosis and its oral health implications. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2019, 28, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benz, K.; Baulig, C.; Knippschil, S.; Strietzel, F.P.; Hunzelmann, N.; Jackowski, J. Prevalence of Oral and Maxillofacial Disorders in Patients with Systemic Scleroderma—A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembélé, I.A.; Nyanke, N.R.; Traore, D.; Souckho, A.K.; Sy, D.; Cissoko, M.; Sanogo, A.; Sangaré, B.B.; Cisse, O.A.; Dao, K.; et al. Scleroderma and HIV Infection: A Case Report with Literature Review. Open. J. Intern. Med. 2018, 8, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosquera, J.A.; Ojea, R.; Navarro, C. HIV Infection Associated with Scleroderma: Report of Two New Cases. J. Clin. Pathol. 2010, 63, 852–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikdar, S.; Grover, C.; Kubba, S.; Yadav, A.; Sahni, V.; Aggarwal, G.; Singh, N.P.; Agarwal, S.K. An Uncommon Cause of Scleroderma. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 2005, 34, 242–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, B.Y.; Reveille, J.D. Rheumatic manifestations associated with HIV in the highly active antiretroviral therapy era. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2009, 21, 404–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, L.l.; Kirchner, E.; Shrestha, R. Rheumatic complications of human immunodeficiency virus infection in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy: Emergence of a new syndrome of immune reconstitution and changing patterns of disease. Semin. Arthritis. Rheum. 2005, 35, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Yen, Y.F.; Lan, Y.C.; Jen, I.A.; Chuang, P.H.; Lee, C.Y.; Lee, Y.; Lin, Y.-A.; Chen, Y.M.A. Risk of diffuse infiltrative lymphocytosis syndrome in HIV-infected patients: A nationwide population-based cohort study. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2018, 79, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parperis, K.; Abdulqader, Y.; Myers, R.; Bhattarai, B.; Al-Ani, M. Rheumatic diseases in HIV-infected patients in the postantiretroviral therapy era: A tertiary care center experience. Clin. Rheumatol. 2019, 38, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.J.; Tsai, M.S.; Sun, H.Y.; Hsieh, S.M.; Chen, M.Y.; Sheng, W.H.; Chang, S.-C. Autoimmune diseases-related arthritis in HIV infected patients in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2015, 48, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Q.; Frank, M.; Glynn, M.; Altman, R.D. Rheumatic Manifestations in HIV-1 Infected In-Patients and Literature Review. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2008, 26, 799–806. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yen, Y.F.; Chuang, P.H.; Jen, I.A.; Chen, M.; Lan, Y.C.; Liu, Y.L.; Lee, Y.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Y.M. Incidence of Autoimmune Diseases in a Nationwide HIV/AIDS Patient Cohort in Taiwan, 2000–2012. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2016, 76, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokop, J.; Jagodzinski, P. Identification of retroviral conserved pol sequences in serum of mixed connective tissue disease and systemic sclerosis patients. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2004, 58, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, S.A.; Diaz, A.; Khalili, K. Retroviruses and the pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis. Int. Rev. Immunol. 1995, 12, 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douvas, A.; Takehana, Y.; Ehresmann, G.; Chernyovskiy, T.; Daar, E.S. Neutralization of HIV type 1 infectivity by serum antibodies from a subset of autoimmune patients with mixed connective tissue disease. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 1996, 12, 1509–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Query, C.C.; Keene, J.D. A human autoimmune protein associated with U1 RNA contains a regional homology that is cross-reactive with retroviral p30gag antigen. Cell 1987, 51, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maul, G.G.; Jimenez, S.A.; Riggs, E.; Ziemnicka-Kotula, D. Determination of an epitope of the diffuse systemic sclerosis marker antigen DNA topoisomerase I: Sequence similarity with retroviral p30gag protein suggests a possible cause for autoimmunity in systemic sclerosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1989, 86, 8492–8496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altice, F.; Evuarherhe, O.; Shina, S.; Carter, G.; Beaubrun, A.C. Adherence to HIV treatment regimens: Systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2019, 13, 475–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deeks, S.G.; Archin, N.; Cannon, P.; Collins, S.; Jones, R.B.; de-Jong, M.A.W.P.; Lambotte, O.; Lamplough, R.; Ndung’u, T.; Sugarman, J.; et al. Research priorities for an HIV cure: International AIDS Society Global Scientific Strategy 2021. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 2085–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixit, S.; Kalkur, C.; Sattur, A.P.; Bornstein, M.M.; Melton, F. Scleroderma and dentistry: Two case reports. J. Med. Case Rep. 2016, 10, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbot, S.; Bossingham, D.; Proudman, S.; de-Costa, C.; Ho-Huynh, A. Risk factors for the development of systemic sclerosis: A systematic review of the literature. Rheumatol. Adv. Pract. 2018, 2, rky041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, B.J.; Tan, K.B.; Pett, S.L.; Cooper, D.A.; Kossard, S.; Whitfeld, M.J. Enfuvirtide injection site reactions: A clinical and histopathological appraisal. Australas. J. Dermatol. 2011, 52, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anbiaee, N.; Tafakhori, Z. Early diagnosis of progressive systemic sclerosis (scleroderma) from a panoramic view: Report of three cases. Dentomaxillofac. Radiol. 2011, 40, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellicano, C.; Leodori, G.; Innocenti, G.P.; Gigante, A.; Rosato, E. Microbiome, Autoimmune Diseases and HIV Infection: Friends or Foes? Nutrients 2019, 11, 2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butera, A.; Gallo, S.; Pascadopoli, M.; Maiorani, C.; Milone, A.; Alovisi, M.; Scribante, A. Paraprobiotics in Non-Surgical Periodontal Therapy: Clinical and Microbiological Aspects in a 6-Month Follow-Up Domiciliary Protocol for Oral Hygiene. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butera, A.; Gallo, S.; Pascadopoli, M.; Taccardi, D.; Scribante, A. Home oral care of periodontal patients using antimicrobial gel with postbiotics, lactoferrin, and aloe barbadensis leaf juice powder vs. conventional chlorhexidine gel: A split-mouth randomized clinical trial. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hachulla, E.; Agard, C.; Allanore, Y.; Avouac, J.; Bader-Meunier, B.; Belot, A.; Berezne, A.; Bouthors, A.-S.; Condette-Wojtasik, G.; Constans, J.; et al. French recommendations for the management of systemic sclerosis. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2021, 16, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajani, A.H.; Nesbitt, S.D. Gingival hyperplasia in a patient with hypertension. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2008, 10, 863–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thombs, B.D.; Taillefer, S.S.; Hudson, M.; Baron, M. Depression in patients with systemic sclerosis: A systematic review of the evidence. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2007, 57, 1089–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mainassara-Chékaraou, S.; El-Gaouzi, R.; Taleb, B. Oral manifestations of morphea en plaque: Case report. Ann. Med. Surg. 2021, 71, 102891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| S. No. | Investigation | Results |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | HIV Status | |

| HIV Serology | HIV-1 + ve (retro + ve since 2012) TLE regimen of ART | |

| CD4 cell count | 440 cells/mm3 | |

| HIV viral load | 2,214,173 copies/mL | |

| 2. | Complete Blood Count (CBC) | |

| Hemoglobin (Hb) | 6.8 g/dL | |

| Total leucocyte count (TLC) | 4490 cells/μL | |

| Platelets | 1.3 lakh platelets/μL | |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) | 85 mm/hr | |

| Bleeding time (BT) | 80 s | |

| Clotting time (CT) | 42 s | |

| International normalized ratio (INR) | 1.5 | |

| 3. | Liver function test (LFT) | |

| Albumin | 2.3 g/dL | |

| Globulin | 1.0 g/dL | |

| Bilirubin | 2.6 mg/dL | |

| Alanine transaminase (ALT) | 71 units/L serum | |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) | 33 units/L serum | |

| Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) | 672 IU/L | |

| Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBs Ag) | −ve | |

| Anti HCV antibody | −ve | |

| α-Feto protein (AFP) | 34 ng/mL | |

| 4. | Kidney function test (KFT) | |

| Na+/K+ | 141/4.1 mEq/L | |

| Urea | 21 mg/dL | |

| Creatinine | 0.4 mg/dL | |

| Urine (R/M) | Normal range | |

| 5. | Immunologic profile | |

| Antinuclear Antibodies (ANA) | 1:1000 (Intensity 4+) | |

| Extractable Nuclear Antigens (ENA) profile (ELISA) | ||

| Anti ds-DNA autoantibody | −ve | |

| Ro (SSA) and La (SSB) autoantibody | −ve | |

| Anti Smantibodies | −ve | |

| Auto-RNP Ab | −ve | |

| Anti Scl-70- Ab | +ve (32.96 units/mL) | |

| Anti-mitrochondrial Ab (AMA) | +ve (suggestive of autoimmune hepatitis) | |

| Anti smooth muscle Ab (ASMA) | +ve (suggestive of autoimmune hepatitis) | |

| Anti cyclic citrullinated peptide (Anti-CCP) | −ve | |

| Anti cerulopasmin Ab | −ve | |

| 6. | Radiographic investigations | |

| USG Abdomen | Mild coarse liver echotexture with surface nodularity, mild ascites | |

| Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) | Gall bladder cholestasis; hepatomegaly with chronic liver disease; splenomegaly with pulmonary hypertension; bilateral single renal cortical cyst; normal common bile duct (CBD); right and left hepatic ducts and intrahepatic bile duct | |

| High-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) | Ground glass opacity with peripheral and sub-pleural distribution suggestive of early stage interstitial lung disease | |

| 7. | Liver Biopsy | Revealed liver cirrhosis with activity compatible with autoimmune hepatitis |

| 8. | Current Treatment Regimen | |

| Table Methotrexate | 15 mg weekly | |

| Table Folvite | 5 mg weekly | |

| Table Omnacortical | 5 mg OD | |

| Table Hydroquinone (HCQ) | 200 mg OD HS | |

| Table Calcitin-D | 500 mg BD | |

| Table Autrin | 10 mg OD | |

| Table Etoricoxib | 90 mg OD HS | |

| Table Pantop | 40 mg OD | |

| S. No | Author(s) and Year | Age/Sex | HIV Status | Systemic Sclerosis Features | Other Associated Ailments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Sikdar et al., 2005 [18] Simultaneous diagnosis of HIV and SSc | 45/F | CD4+ lymphocyte count increase observed after 6 months HAART. | The patient developed symptoms of SSc in the background of immune suppression and responded well to steroids and HAART therapy | - |

| 2. | Mosquera JA, et al., 2010 [17] | 44/M | HIV +ve, CD4 cell count = 934 cells/mm3, viral load < 40 copies/mL | Tumification of forearms, thighs, and legs; Raynaud’s phenomena +ve; skin biopsy revealed scleroderma features | +ve HCV serology |

| 3. | Mosquera JA, et al., 2010 [17] | 42/M | Stage II HIV infection | Skin thickening with spasticity in legs; skin biopsy revealed SSc features | +ve HCV and HBV serology; type II diabetes mellitus |

| 4. | Okongo LO, et al., 2014 [5] | 9/F | Perinatally acquired HIV; on ART therapy; CD4 cell count = 879 cells/mm3; lower than detectable viral load | Raynaud’s phenomena +ve with fingertip ulceration and digital ischemia; thickened extremities and torso skin; B/L sclerodactyly with limited extension and flexion of fingers | Completed TB therapy at 6 months |

| 5. | Dembelae IA et al., 2018 [16] Concomitant diagnosis of HIV and systemic sclerosis. | 56/F | HIV stage III | Sclerodactyly; +ve Raynaud’s phenomena; +ve anti Scl-70 Abs | +ve HBV serology |

| 6. | Yao Q, et al., 2008 [24] Retrospective study; out of 888 HIV diagnosed cases, only 1 case of SSc was seen | 45/F | HIV +ve (acquired from heterosexual partner) | Progressive stiffening of face and extremities skin, mask-like face | Renal insufficiency |

| 7. | Yen et al., 2016 [25] Only 4 cases of SSc out of 20,444 HIV cases | 3 males and 1 female | 1 patient on HAART and 3 patients without HAART | - | - |

| Author (s) and Year | Autoantigen | Viral Antigen |

|---|---|---|

| Douvas et al., 1996 [28] | U1 RNP 70 kD; seen in MCTD and SSc | HIV gp120/41 envelope complex |

| Query CC et al., 1987 [29] | U1 RNP 70 kD; seen in MCTD and SSc | Retroviral p30 gag protein |

| Maul GG et al., 1989 [30] | DNA Topoisomerase I 110 kD; seen in diffuse SSc | Retroviral p30 gag protein |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hasan, S.; Aqil, M.; Panigrahi, R. HIV-Associated Systemic Sclerosis: Literature Review and a Rare Case Report. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10066. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610066

Hasan S, Aqil M, Panigrahi R. HIV-Associated Systemic Sclerosis: Literature Review and a Rare Case Report. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(16):10066. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610066

Chicago/Turabian StyleHasan, Shamimul, Mohd. Aqil, and Rajat Panigrahi. 2022. "HIV-Associated Systemic Sclerosis: Literature Review and a Rare Case Report" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 16: 10066. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610066

APA StyleHasan, S., Aqil, M., & Panigrahi, R. (2022). HIV-Associated Systemic Sclerosis: Literature Review and a Rare Case Report. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(16), 10066. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610066