Career Aspiration Fulfillment and COVID-19 Vaccination Intention among Nigerian Youth: An Instrumental Variable Approach

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data and Sampling Procedures

2.2. Specification of Instrumental Variable Probit Model

3. Results

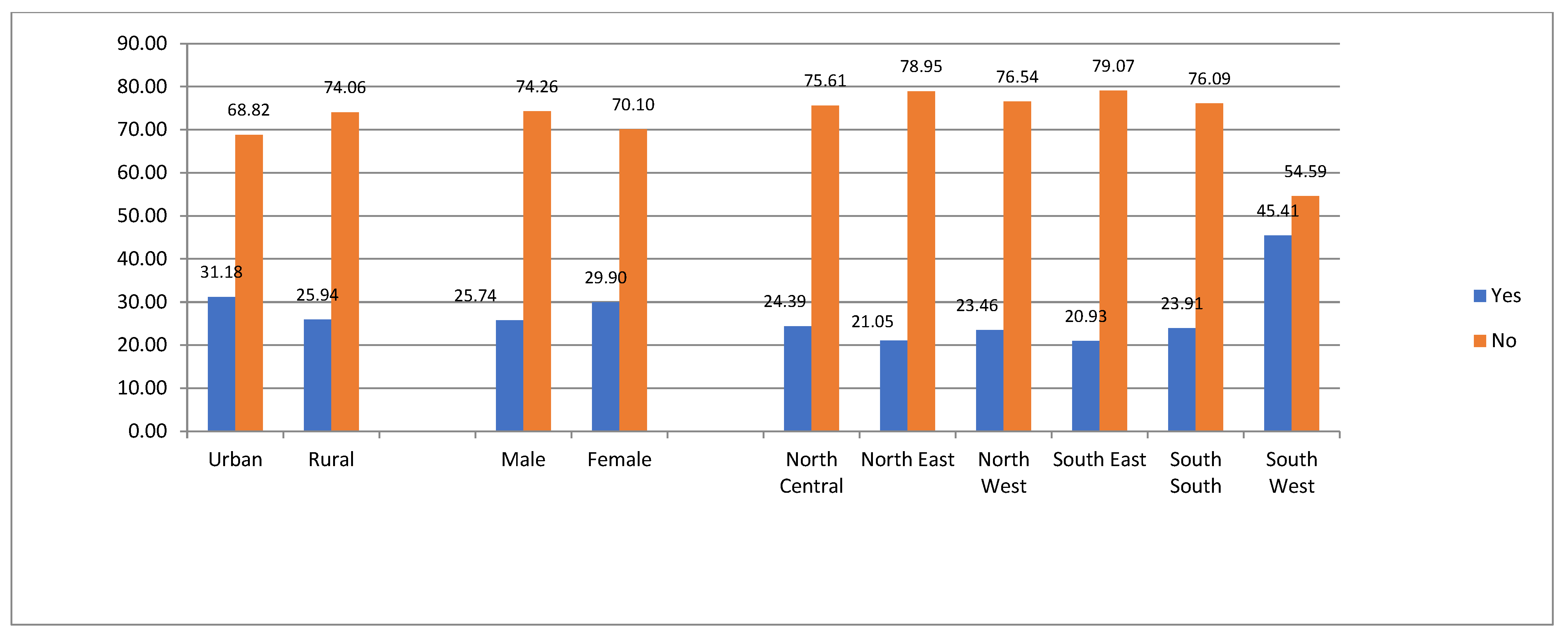

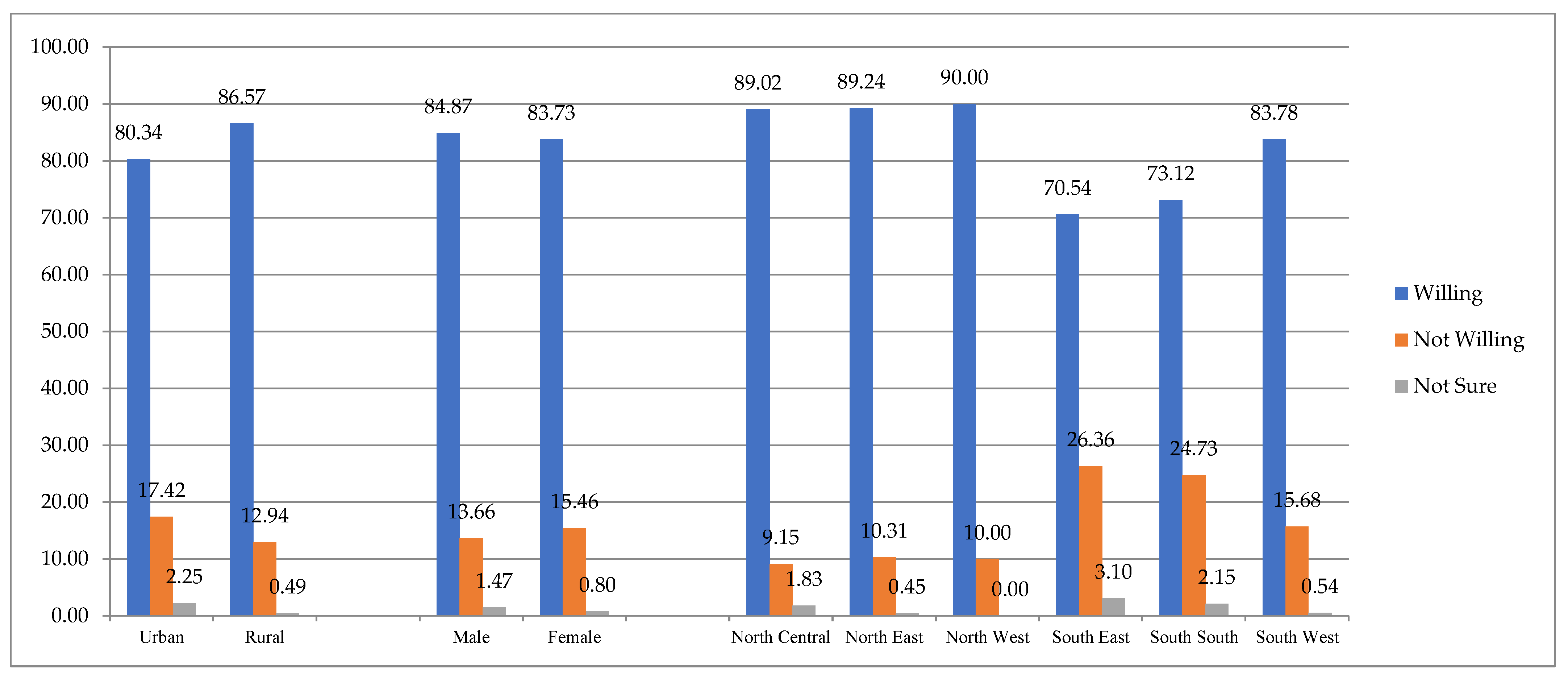

3.1. Youths Demographic Characteristics, Dream Job Engagement and Vacine Hesitancy

3.2. Probit Regression Results of the Determinants of Dream Jobs Engagement

3.3. IV Probit Results of the Determinants of Youths Willingness to Take COVID-19 Vaccines

4. Discussion

4.1. Fulfillment of Career Aspirations among the Youths

4.2. Youths’s Willingness to Take COVID-19 Vaccines

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Bank. Food Security and COVID-19. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/agriculture/brief/food-security-and-covid-19 (accessed on 22 August 2021).

- Joseph-Raji; Noel, G.A.S.; Ore, M.A.H.; Timmis, M.A.; Ogebe, E.; Rostom, J.O.; Cortes, A.M.T.; Kojima, M.; Lee, M.; Okou, Y.M.; et al. Resilience through Reforms; Nigeria Development Update; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; Available online: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/389281623682704986/Resilience-through-Reforms (accessed on 15 March 2022).

- World Bank. GDP Growth Rates- Nigeria. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG?locations=NG (accessed on 12 March 2022).

- Adegboyega, A. IMF Raises Nigeria’s 2022 Economic Growth Forecast. 2022. Available online: https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/more-news/524686-imf-raises-nigerias-2022-economic-growth-forecast.html (accessed on 2 March 2022).

- World Bank. A Better Future for All Nigerians, Nigeria Poverty Assessment 2022 Report; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/infographic/2022/03/21/afw-nigeria-poverty-assessment-2022-a-better-future-for-all-nigerians (accessed on 19 March 2022).

- Federal Ministry of Youth and Sports Development. Nigerian Youth Employment Action Plan 2021–2024. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---africa/---ro-abidjan/---ilo-abuja/documents/publication/wcms_819111.pdf (accessed on 25 March 2022).

- Sowunmi, O.A. Job satisfaction, personality traits, and its impact on motivation among mental health workers. S. Afr. J. Psychiat. 2022, 28, a1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etuk, G.R.; Alobo, E.T. Determinants of job dissatisfaction among employees in formal organizations in Nigeria. Int. J. Dev. Sustain. 2014, 3, 1113–1120. [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner, D.; Goedhuys, M. Youth Aspirations and the Future of Work: A Review of the Literature and Evidence, ILO Working Paper 8 (Geneva, ILO). 2020. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/employment/Whatwedo/Publications/working-papers/WCMS_755248/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 25 March 2022).

- Eccles, J.S. Gender roles and women’s achievement-related decisions. Psychol. Women Q. 1987, 11, 135–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, J.S. Studying gender and ethnic differences in participation in math, physical science, and information technology. New Dir. Child Adol. Dev. 2005, 110, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Appadurai, A. The Capacity to Aspire: Culture and the Terms of Recognition; Rao, V., Walton, M., Eds.; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 2004; Available online: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=4kGJ86s8MB4C&dq=Culture+and+Public+Action&printsec=frontcover&source=bn&hl=en&ei=PgiASobnLs6NjAeimq3xAQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed on 25 March 2022).

- Ray, D. Aspirations, Poverty and Economic Change; Banerjee, A.V., Bénabou, R., Mookherjee, D., Eds.; Understanding Poverty; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Animasahun, R.O. Increasing the problem-solving skills of students with developmental disabilities participating in general education. Remedial Spec. Educ. 2007, 23, 279–288. [Google Scholar]

- Leong, R.W.; Gupta, T.B. Learning Disabilities: Theories, Diagnosis and Teaching Strategies, 7th ed.; Houghton Mifflin Company: Boston, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Olanrewaju, M.K.; Olabisi, O.L.; Olabisi, P.B. Determinants of Career Aspirations Among Selected Junior Secondary School Students in Oyo State. J. Lexicogr. Terminol. 2022, 2, 26–39. [Google Scholar]

- Goodale, T.W.; Hall, D.K. Circumscription and compromise. A developmental theory of occupational aspirations. J. Couns. Psychol. 2016, 28, 545–579. [Google Scholar]

- Onoyase, B.N.; Onoyase, T.Y. Career Guidance and Counselling; Goldprints Publishers: Lagos, Nigeria, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Owoyele, J.W.; Muraina, K.O. Predictive Influence of Parental Factors on Career Choice among School-going Adolescents in South-West, Nigeria. Acad. J. Couns. Educ. Psychol. (AJCEP) 2015, 1, 172–184. [Google Scholar]

- Olu-Abiodun, O.; Abiodun, O.; Okafor, N. COVID-19 vaccination in Nigeria: A rapid review of vaccine acceptance rate and the associated factors. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0267691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olomofe, C.O.; Soyemi, V.K.; Udomah, B.F.; Owolabi, A.O.; Ajumuka, E.E.; Igbokwe, C.M.; Ashaolu, U.O.; Adeyemi, A.O.; Aremu-Kasumu, Y.B.; Dada, O.; et al. Predictors of uptake of a potential COVID-19 vaccine among Nigerian adults. medRxiv 2021. [CrossRef]

- Adejumo, O.A.; Ogundele, O.A.; Madubuko, C.R.; Oluwafemi, R.O.; Okoye, O.C.; Okonkwo, K.C.; Owolade, S.S.; Junaid, O.A.; Lawal, O.M.; Enikuomehin, A.C.; et al. Perceptions of the COVID-19 vaccine and willingness to receive vaccination among health workers in Nigeria. Osong Public Health Res. Perspect. 2021, 12, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliyasu, Z.; Umar, A.A.; Abdullahi, H.M.; Kwaku, A.A.; Amole, T.G.; Tsiga-Ahmed, F.I.; Garba, R.M.; Salihu, H.M.; Aliyu, M.H. “They have produced a vaccine, but we doubt if COVID-19 exists”: Correlates of COVID-19 vaccine acceptability among adults in Kano, Nigeria. Human Vaccines Immunother. 2021, 17, 4057–4064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobin, E.A.; Okonofua, M.; Azeke, A. Acceptance of a COVID-19 Vaccine in Nigeria: A Population-Based Cross-Sectional Study. Ann. Med. Health Sci. Res. 2021, 11, 1145–1152. [Google Scholar]

- Enitan, S.; Oyekale, A.; Akele, R.; Olawuyi, K.; Olabisi, E.; Nwankiti, A.; Enitan, C.B. Assessment of Knowledge, Perception and Readiness of Nigerians to participate in the COVID-19 Vaccine Trial. Int. J. Vaccines Immun. 2020, 4, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Allagoa, D.O.; Oriji, P.C.; Tekenah, E.S.; Obagah, L.; Njoku, C.; Afolabi, A.S.; Atemie, G. Predictors of acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine among patients at a tertiary hospital in South-South Nigeria. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 2021, 8, 2165–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, E.D.; Wilson, P.; Eleki, B.J.; Wonodi, W. Knowledge, acceptance, and hesitancy of COVID-19 vaccine among health care workers in Nigeria. MGM J. Med. Sci. 2021, 8, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzochukwu, I.C.; Eleje, G.U.; Nwankwo, C.H.; Chukwuma, G.O.; Uzuke, C.A.; Uzochukwu, C.E.; Mathias, B.A.; Okunna, C.S.; Asomugha, L.A.; Esimone, C.O. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among staff and students in a Nigerian tertiary educational institution. Ther. Adv. Infect. Dis. 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyekale, A.S. Factors Influencing Willingness to Be Vaccinated against COVID-19 in Nigeria. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatunmole, M. The Nigerian Government Will Begin the Enforcement of Compulsory COVID-19 Vaccination for All Its Employees Effective December 1. 14 October 2021. Available online: https://www.icirnigeria.org/nigeria-begins-enforcement-of-compulsory-covid-19-vaccine-for-workers-on-december-1/ (accessed on 2 August 2022).

- Odusote, A. Compulsory COVID-19 vaccination in Nigeria? Why It’s Illegal, and a Bad Idea. 8 September 2021. Available online: https://theconversation.com/compulsory-covid-19-vaccination-in-nigeria-why-its-illegal-and-a-bad-idea-167396 (accessed on 2 August 2022).

- Davis, T.P.; Yimam, A.K.; Kalam, A.; Tolossa, A.D.; Kanwagi, R.; Bauler, S.; Kulathungam, L.; Larson, H. Behavioural Determinants of COVID-19-Vaccine Acceptance in Rural Areas of Six Lower- and Middle-Income Countries. Vaccines 2022, 10, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josiah, B.O.; Kantaris, M. Perception of COVID-19 and acceptance of vaccination in Delta State Nigeria. Niger Health J. 2021, 21, 60–86. [Google Scholar]

- Steinert, J.I.; Sternberg, H.; Prince, H.; Fasolo, B.; Galizzi, M.M.; Büthe, T.; Velt, G.A. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in eight European countries: Prevalence, determinants, and heterogeneity. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabm9825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzo, R.R.; Sami, W.; Alam, Z.; Acharya, S.; Jermsittiparsert, K.; Songwathana, K.; Pham, N.T.; Respati, T.; Faller, E.M.; Baldonado, A.M.; et al. Hesitancy in COVID-19 vaccine uptake and its associated factors among the general adult population: A cross-sectional study in six Southeast Asian countries. Trop. Med. Health 2022, 50, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, B.; Helm, S.; Heinz, E.; Barnett, M.; Arora, M. Doubt in store: Vaccine hesitancy among grocery workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Behav. Med. 2022, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dror, A.A.; Eisenbach, N.; Taiber, S.; Morozov, N.G.; Mizrachi, M.; Zigron, A.; Srouji, S.; Sela, E. Vaccine hesitancy: The next challenge in the fight against COVID-19. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2020, 35, 775–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khubchandani, J.; Sharma, S.; Price, J.H.; Wiblishauser, M.J.; Sharma, M.; Webb, F.J. COVID-19 Vaccination Hesitancy in the United States: A Rapid National Assessment. J. Community Health 2021, 46, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanovic, J.; Boucher, V.; Gagne, M.; Gupta, S.; Joyal-Desmarais, K.; Paduano, S.; Aburub, A.; Gorin, S.S.; Kassianos, A.; Ribeiro, P.; et al. Global Trends and Correlates of COVID-19 Vaccination Hesitancy: Findings from the iCARE Study. Vaccines 2021, 9, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, J.; Bakshi, S.; Wasim, A.; Ahmad, M.; Majid, U. What factors promote vaccine hesitancy or acceptance during pandemics? A systematic review and thematic analysis. Health Promot. Int. 2021, 37, daab105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A. Can Employers Ask Job Applicants About Vaccination and COVID-19? Available online: https://www.shrm.org/resourcesandtools/legal-and-compliance/employment-law/pages/coronavirus-can-employers-ask-applicants-about-vaccination.aspx#:~:text=%22While%20asking%20about%20the%20vaccination,vaccination%2C%20should%20be%20reserved%20until (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- Willis, D.E.; Andersen, J.A.; BryantMoore, K.; Selig, J.P.; Long, C.R.; Felix, H.C.; Curran, G.M.; Curran, G.M.; McElfish, P. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: Race/ethnicity, trust, and fear. Clin Transl. Sci. 2021, 14, 2200–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.A.; McFadden, S.M.; Elharake, J.; Omer, S.B. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in the US. eClinicalMedicine 2020, 26, 100495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, K.A.; Bloomstone, S.J.; Walder, J.; Crawford, S.; Fouayzi, H.; Mazor, K.M. Attitudes toward a potential SARS-CoV-2 vaccine: A survey of U.S. adults. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020, 173, 964–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridman, A.; Gershon, R.; Gneezy, A. COVID-19 and vaccine hesitancy: A longitudinal study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0250123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willis, D.E.; Presley, J.; Williams, M.; Zaller, N.; McElfish, P.A. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among youth. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2021, 17, 5013–5015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Bureau of Statistics (NBS). COVID-19 National Longitudinal Phone Survey; Federal Republic of Nigeria, National Bureau of Statistics: Abuja, Nigeria, 2021. Available online: https://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/catalog/3712 (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- Angrist, J.D.; Krueger, A.B. Instrumental Variables and the Search for Identification: From Supply and Demand to Natural Experiments. J. Econ. Perspect. 2001, 15, 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Greenland, S. An Introduction to instrumental variables for epidemiologists. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2000, 29, 722–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernan, M.A.; Robins, J.M. Instruments for Causal Inferenc—An Epidemiologists Dream? Epidemiology 2006, 17, 360–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, J.; Cheng, H.; Bollen, K.A.; Thomas, D.R.; Wang, L. Instrumental variable estimation in ordinal probit models with mismeasured predictors. Can. J. Stat. 2019, 47, 653–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peteranetz, M.; Flanigan, A.E.; Shell, D.F.; Soh, L.-K. Career aspirations, perceived instrumentality, and achievement in undergraduate computer science courses. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2018, 53, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montmarquette, C.; Cannings, K.; Mahseredjian, S. How do young people choose college majors? Econ. Educ. Rev. 2002, 21, 543–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lockwood, P.; Jordan, C.H.; Kunda, Z. Motivation by positive or negative role models: Regulatory focus determines who will best inspire us. J. Pers Soc. Psychol. 2002, 83, 854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, A.; Denis, V.; Schleicher, A.; Ekhtiari, H.; Forsyth, T.; Liu, E.; Chambers, N. Teenagers’ Career Aspirations and the Future of Work. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/berlin/publikationen/Dream-Jobs.pdf (accessed on 25 March 2022).

- Onoyase, A. Causal Factors and Effects of Unemployment on Graduates of Tertiary Institutions in Ogun State South West Nigeria: Implications for Counselling. J. Educ. Soc. Res. 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, K.; Lent, R.W. The roles of family, culture, and social cognitive variables in the career interests and goals of Asian American college students. J. Couns. Psychol. 2018, 65, 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehati, P.; Amaerjiang, N.; Yang, L.; Xiao, H.; Li, M.; Zunong, J.; Wang, L.; Vermund, S.H.; Hu, Y. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among adolescents: Cross-sectional school survey in four Chinese cities prior to vaccine availability. Vaccines 2022, 10, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euser, S.; Kroese, F.M.; Derks, M.; de Bruin, M. Understanding COVID-19 vaccination willingness among youth: A survey study in the Netherlands. Vaccine 2022, 40, 833–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.M.; Hassan, Z.; Muhammad, H.M. Assessment of COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance and Willingness to Pay by Nigerians. Health 2022, 14, 137–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoda, T.; Katsuyama, H. Willingness to Receive COVID-19 Vaccination in Japan. Vaccines 2021, 9, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mean | Std. Err. | 95% Conf. Interval | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lowest Bound | Uppermost Bound | |||

| Willing to be vaccinated (Yes = 1; 0 otherwise) | 0.8429 | - | - | - |

| Urban resident (Yes = 1, 0 otherwise) | 0.3655 | - | - | - |

| Gender (Male = 1, 0 otherwise) | 0.4887 | - | - | - |

| Age of youths (years) | 19.3768 | 0.1014 | 19.1778 | 19.5758 |

| No education (Yes = 1, 0 otherwise) | 0.1078 | - | - | - |

| Primary education (Yes = 1, 0 otherwise) | 0.1448 | - | - | - |

| Secondary education (Yes = 1, 0 otherwise) | 0.6663 | - | - | - |

| Tertiary education (Yes = 1, 0 otherwise) | 0.0811 | - | - | - |

| North Central zone (Yes = 1, 0 otherwise) | 0.1684 | - | - | - |

| North East zone (Yes = 1, 0 otherwise) | 0.2290 | - | - | - |

| North West zone (Yes = 1, 0 otherwise) | 0.1848 | - | - | - |

| South East zone (Yes = 1, 0 otherwise) | 0.1324 | - | - | - |

| South South zone (Yes = 1, 0 otherwise) | 0.0955 | - | - | - |

| South West zone (Yes = 1, 0 otherwise) | 0.1899 | - | - | - |

| Engaged with dream jobs (Yes = 1, 0 otherwise) | 0.2772 | - | - | - |

| Know someone with dream job (Yes = 1, 0 otherwise) | 0.7177 | - | - | - |

| Standard Probit Parameters | Marginal Parameters | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Coefficients | z-Statistics | dy/dx | z-Statistics |

| Know someone with dream job (Yes = 1, 0 otherwise) | 0.5616 *** | 5.11 | 0.1644 *** | 5.75 |

| Migrating to capital cities (Yes = 1, 0 otherwise) | 0.1175 | 1.06 | 0.0376 | 1.06 |

| Migrating to other cities (Yes = 1, 0 otherwise) | 0.0089 | 0.08 | 0.0029 | 0.08 |

| Migrating to rural areas (Yes = 1, 0 otherwise) | −0.2020 | −1.62 | −0.0632 * | −1.66 |

| Migrating to other countries (Yes = 1, 0 otherwise) | −0.0752 | −0.68 | −0.0241 | −0.68 |

| Migrating to no specific place (Yes = 1, 0 otherwise) | −0.0464 | −0.28 | −0.0147 | −0.28 |

| Urban resident (Yes =1, 0 otherwise) | 0.0160 | 0.15 | 0.0051 | 0.15 |

| Gender (Male = 1, 0 otherwise) | 0.0532 | 0.57 | 0.0171 | 0.57 |

| Age of youths (years) | 0.0576 *** | 5.41 | 0.0185 *** | 5.43 |

| Primary education (Yes = 1, 0 otherwise) | −0.4821 *** | −2.67 | −0.1360 *** | −3.12 |

| Secondary education (Yes = 1, 0 otherwise) | −0.5524 *** | −3.57 | −0.1861 *** | −3.46 |

| Tertiary education (Yes = 1, 0 otherwise) | −0.5902 *** | −2.76 | −0.1559 *** | −3.53 |

| North East zone (Yes = 1, 0 otherwise) | −0.0587 | −0.39 | −0.0187 | −0.39 |

| North West zone (Yes = 1, 0 otherwise) | −0.0832 | −0.51 | −0.0262 | −0.52 |

| South East zone (Yes =1, 0 otherwise) | −0.0142 | −0.08 | −0.0045 | −0.08 |

| South South zone (Yes = 1, 0 otherwise) | 0.1389 | 0.74 | 0.0462 | 0.71 |

| South West zone (Yes = 1, 0 otherwise) | 0.6728 *** | 4.25 | 0.2390 *** | 4.02 |

| Constant | −1.9650 *** | −4.87 | ||

| Diagnostic statistics | ||||

| Number of observations | 974 | |||

| LR chi2(17) | 115.73 *** | |||

| Log likelihood | −517.08 | |||

| Coefficient | Std Error | z-Statistics | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Engagement with dream job (Yes = 1, 0 otherwise) | 1.233 *** | 0.4349 | 2.84 |

| Migrating with capital cities preference (Yes = 1, 0 otherwise) | −0.0025 | 0.1140 | −0.02 |

| Migrating with other cities preference (Yes = 1, 0 otherwise) | 0.0777 | 0.1115 | 0.70 |

| Migrating with rural areas preference (Yes = 1, 0 otherwise) | 0.2780 ** | 0.1283 | 2.17 |

| Migrating to countries preference (Yes = 1, 0 otherwise) | 0.0756 | 0.1118 | 0.68 |

| Migrating no specific place preference (Yes = 1, 0 otherwise) | 0.2543 | 0.1691 | 1.50 |

| North East zone (Yes = 1, 0 otherwise) | −0.0682 | 0.1597 | −0.43 |

| North West zone (Yes = 1, 0 otherwise) | −0.0138 | 0.1707 | −0.08 |

| South East zone (Yes = 1, 0 otherwise) | −0.6166 *** | 0.1889 | −3.26 |

| South South zone (Yes = 1, 0 otherwise) | −0.5573 *** | 0.1883 | −2.96 |

| South West zone (Yes = 1, 0 otherwise) | −0.3825 ** | 0.1849 | −2.07 |

| Urban resident (Yes = 1, 0 otherwise) | −0.2021 * | 0.1077 | −1.88 |

| Gender (Male = 1, 0 otherwise) | −0.0217 | 0.0932 | −0.23 |

| Primary education (Yes = 1, 0 otherwise) | 0.0659 | 0.2122 | 0.31 |

| Secondary education (Yes = 1, 0 otherwise) | 0.1239 | 0.1927 | 0.64 |

| Tertiary education (Yes = 1, 0 otherwise) | −0.1140 | 0.2659 | −0.43 |

| Age of youths (years) | −0.0290 ** | 0.0140 | −2.07 |

| Constant | 0.7948 * | 0.4142 | 1.92 |

| Athrho | −0.6904 *** | 0.2691 | −2.57 |

| Lnsigma | −0.8650 *** | 0.0227 | −38.18 |

| Rho | −0.5982 *** | 0.1728 | |

| Sigma | 0.4210 | 0.0095 | |

| Other diagnostic statistics | |||

| Number of observations | 974 | ||

| Wald chi2(17) | 94.41 *** | ||

| Wald test of exogeneity | 6.58 *** |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oyekale, A.S. Career Aspiration Fulfillment and COVID-19 Vaccination Intention among Nigerian Youth: An Instrumental Variable Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9813. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19169813

Oyekale AS. Career Aspiration Fulfillment and COVID-19 Vaccination Intention among Nigerian Youth: An Instrumental Variable Approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(16):9813. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19169813

Chicago/Turabian StyleOyekale, Abayomi Samuel. 2022. "Career Aspiration Fulfillment and COVID-19 Vaccination Intention among Nigerian Youth: An Instrumental Variable Approach" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 16: 9813. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19169813

APA StyleOyekale, A. S. (2022). Career Aspiration Fulfillment and COVID-19 Vaccination Intention among Nigerian Youth: An Instrumental Variable Approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(16), 9813. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19169813