Exploring Determinants of Compassionate Cancer Care in Older Adults Using Fuzzy Cognitive Mapping

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

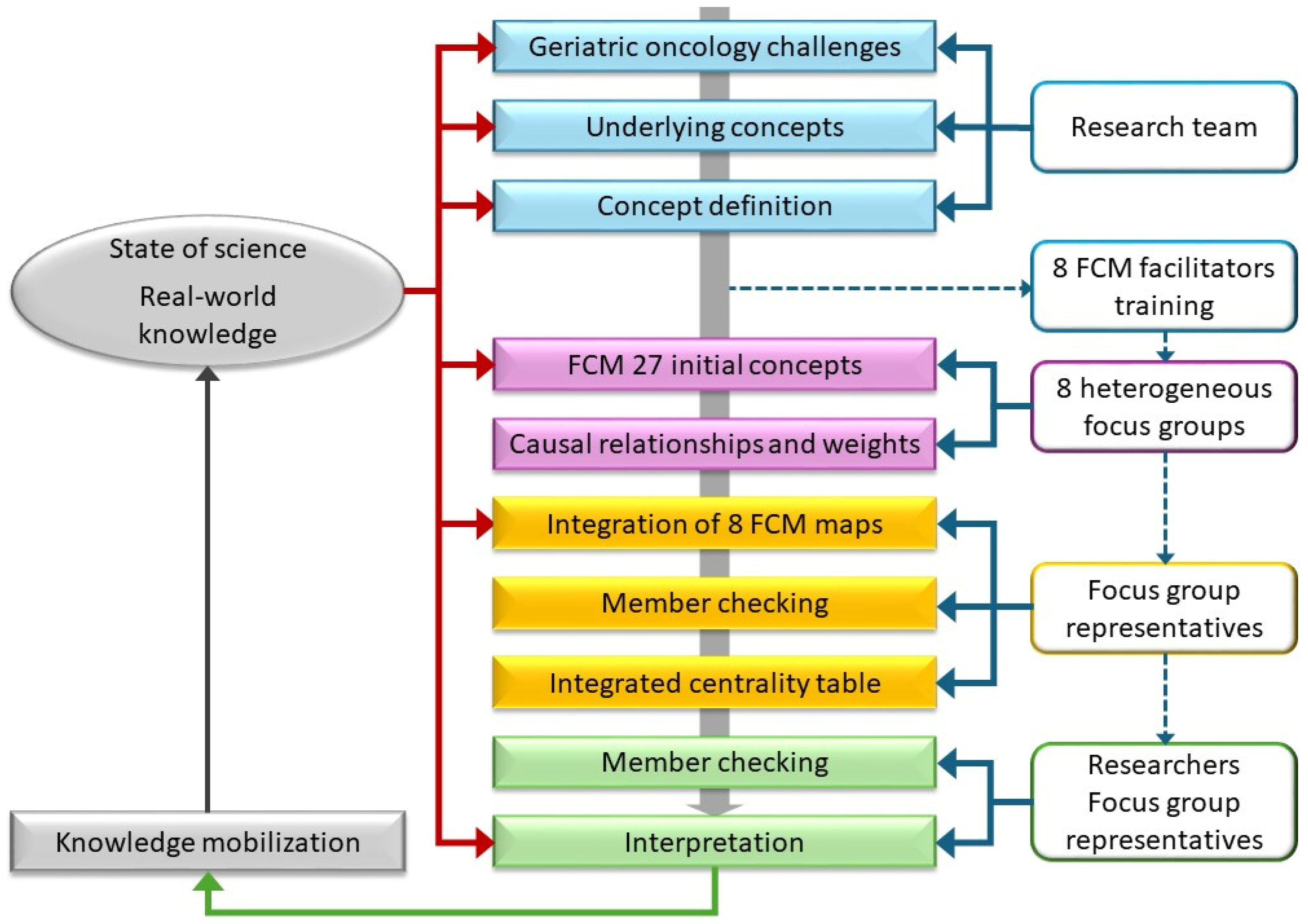

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Fuzzy Cognitive Mapping Procedure

2.3.1. Preparation

2.3.2. Data Collection During the FCM Session

2.3.3. Analysis

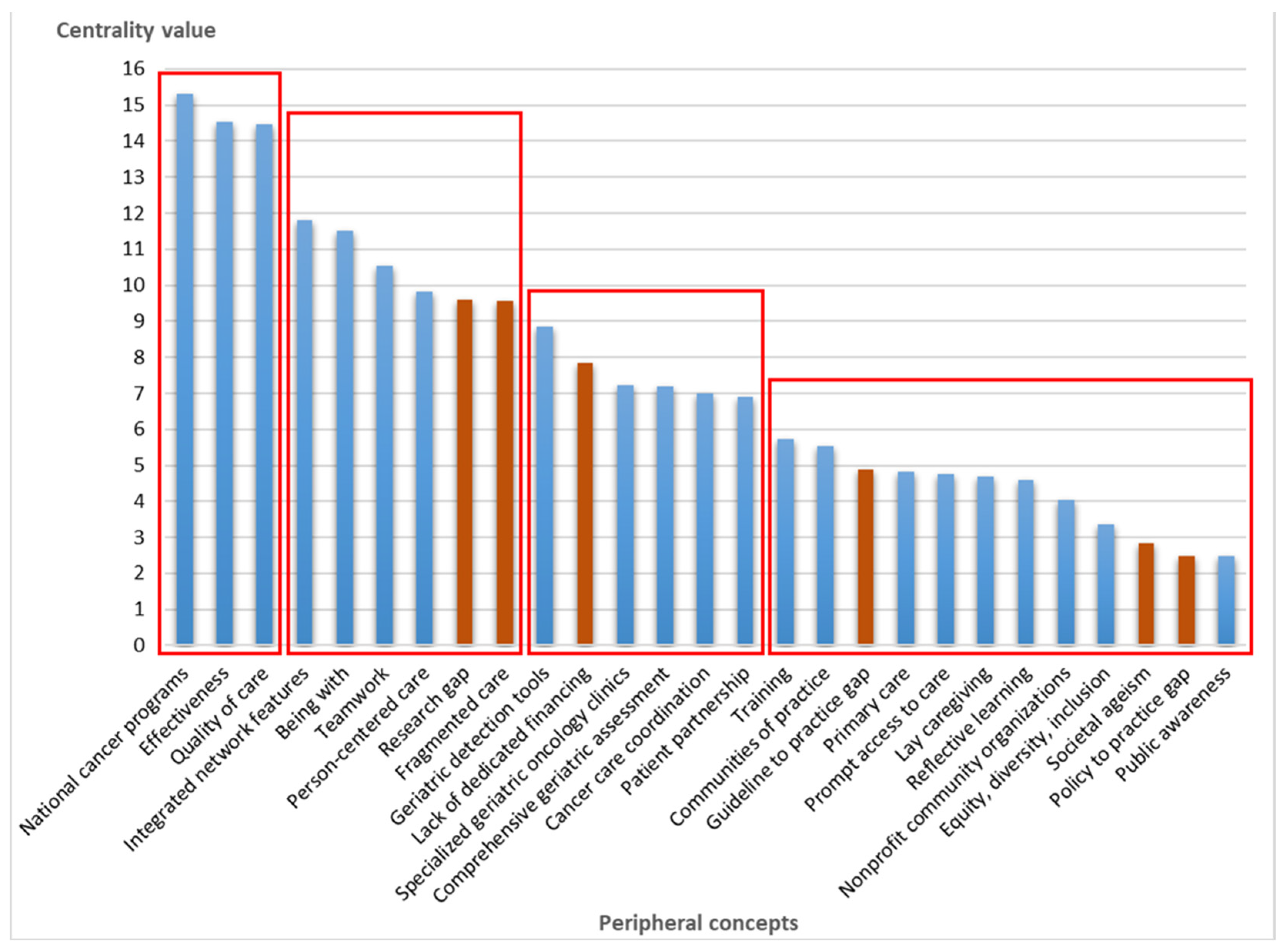

3. Results

3.1. Compassionate Care as a Core Concept for Improvement

3.2. Relationship Between Compassionate Care and Peripheral Concepts

4. Discussion

4.1. Promoting Compassionate Care at the Systemic Level

4.2. Integrating Compassionate Care at the Organizational Level

4.3. Translating Compassionate Care into Real-World Practice

4.4. Bridging Health Systems and Societal Context

4.5. Implications

4.6. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| C | Centrality |

| FCM | Fuzzy cognitive mapping |

| PRISM | Practical robust implementation and sustainability model |

| RE-AIM | Reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, maintenance |

| SIOG | International Society of Geriatric Oncology |

References

- World Health Organization. Cancer. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Scotté, F.; Bossi, P.; Carola, E.; Cudennec, T.; Dielenseger, P.; Gomes, F.; Knox, S.; Strasser, F. Addressing the quality of life needs of older patients with cancer: A SIOG consensus paper and practical guide. Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29, 1718–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, S.; Alibhai, S.; Mehta, R.; Savard, M.-F.; Mariano, C.; LeBlanc, D.; Desautels, D.; Pezo, R.; Zhu, X.; Gelmon, K.A.; et al. Improving care for older adults with cancer in Canada: A call to action. Curr. Oncol. 2024, 31, 3783–3797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coll, P.P.; Korc-Grodzicki, B.; Ristau, B.T.; Shahrokni, A.; Koshy, A.; Filippova, O.T.; Ali, I. Cancer prevention and screening for older adults: Part 2. Interventions to prevent and screen for breast, prostate, cervical, ovarian, and endometrial cancer. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2020, 68, 2684–2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, S.; Donnan, P.; Buchanan, D.; Smith, B.H. Age and cancer type: Associations with increased odds of receiving a late diagnosis in people with advanced cancer. BMC Cancer 2023, 23, 1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedrak, M.S.; Freedman, R.A.; Cohen, H.J.; Muss, H.B.; Jatoi, A.; Klepin, H.D.; Wildes, T.M.; Le-Rademacher, J.G.; Kimmick, G.G.; Tew, W.P.; et al. Older adult participation in cancer clinical trials: A systematic review of barriers and interventions. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DuMontier, C.; Loh, K.P.; Bain, P.A.; Silliman, R.A.; Hshieh, T.; Abel, G.A.; Djulbegovic, B.; Driver, J.A.; Dale, W. Defining undertreatment and overtreatment in older adults with cancer: A scoping literature review. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 2558–2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, G.R.; Pisu, M.; Rocque, G.B.; Williams, C.P.; Taylor, R.A.; Kvale, E.A.; Partridge, E.E.; Bhatia, S.; Kenzik, K.M. Unmet social support needs among older adults with cancer. Cancer 2019, 125, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puts, M.T.E.; Papoutsis, A.; Springall, E.; Tourangeau, A.E. A systematic review of unmet needs of newly diagnosed older cancer patients undergoing active cancer treatment. Support. Care Cancer 2012, 20, 1377–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks, R.; Cheung, K.-L. Challenges in geriatric oncology—A surgeon’s perspective. Curr. Oncol. 2022, 29, 659–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seghers, P.A.L.; Alibhai, S.M.H.; Battisti, N.M.L.; Kanesvaran, R.; Extermann, M.; O’Donovan, A.; Pilleron, S.; Mislang, A.R.; Musolino, N.; Cheung, K.-L.; et al. Geriatric assessment for older people with cancer: Policy recommendations. Glob. Health Res. Policy 2023, 8, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soo, W.K.; Yin, V.; Crowe, J.; Lane, H.; Steer, C.B.; Dārziņš, P.; Davis, I.D. Integrated care for older people with cancer: A primary care focus. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2023, 4, e243–e245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tremblay, D.; Charlebois, K.; Terret, C.; Joannette, S.; Latreille, J. Integrated oncogeriatric approach: A systematic review of the literature using concept analysis. BMJ Open 2012, 2, e001483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Extermann, M.; Brain, E.; Canin, B.; Cherian, M.N.; Cheung, K.-L.; de Glas, N.; Devi, B.; Hamaker, M.; Kanesvaran, R.; Karnakis, T. Priorities for the global advancement of care for older adults with cancer: An update of the International Society of Geriatric Oncology Priorities Initiative. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, e29–e36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohile, S.G.; Dale, W.; Somerfield, M.R.; Schonberg, M.A.; Boyd, C.M.; Burhenn, P.S.; Canin, B.; Cohen, H.J.; Holmes, H.M.; Hopkins, J.O.; et al. Practical assessment and management of vulnerabilities in older patients receiving chemotherapy: ASCO guideline for geriatric oncology. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 2326–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Union for International Cancer Control (UICC). Cancer and Ageing. Available online: https://www.uicc.org/what-we-do/thematic-areas/cancer-and-ageing (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- VanderWalde, N.; Jagsi, R.; Dotan, E.; Baumgartner, J.; Browner, I.S.; Burhenn, P.; Cohen, H.J.; Edil, B.H.; Edwards, B.; Extermann, M.; et al. NCCN guidelines insights: Older adult oncology, Version 2.2016. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2016, 14, 1357–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dotan, E.; Walter, L.C.; Browner, I.S.; Clifton, K.; Cohen, H.J.; Extermann, M.; Gross, C.; Gupta, S.; Hollis, G.; Hubbard, J.; et al. NCCN Guidelines® Insights: Older adult oncology, version 1.2021. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2021, 19, 1006–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Extermann, M.; Aapro, M.; Audisio, R.; Balducci, L.; Droz, J.-P.; Steer, C.; Wildiers, H.; Zulian, G. Main priorities for the development of geriatric oncology: A worldwide expert perspective. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2011, 2, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malenfant, S.; Jaggi, P.; Hayden, K.A.; Sinclair, S. Compassion in healthcare: An updated scoping review of the literature. BMC Palliat. Care 2022, 21, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, M.; Korman, M.B.; Aliasi-Sinai, L.; den Otter-Moore, S.; Conn, L.G.; Murray, A.; Jacobson, M.C.; Enepekides, D.; Higgins, K.; Ellis, J. Understanding compassionate care from the patient perspective: Highlighting the experience of head and neck cancer care. Can. Oncol. Nurs. J. 2023, 33, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, S.; McClement, S.; Raffin-Bouchal, S.; Hack, T.F.; Hagen, N.A.; McConnell, S.; Chochinov, H.M. Compassion in health care: An empirical model. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2016, 51, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, S.; Norris, J.M.; McConnell, S.J.; Chochinov, H.M.; Hack, T.F.; Hagen, N.A.; McClement, S.; Bouchal, S.R. Compassion: A scoping review of the healthcare literature. BMC Palliat. Care 2016, 15, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frampton, S.B.; Guastello, S.; Lepore, M. Compassion as the foundation of patient-centered care: The importance of compassion in action. J. Comp. Eff. Res. 2013, 2, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiansen, A.; O’Brien, M.R.; Kirton, J.A.; Zubairu, K.; Bray, L. Delivering compassionate care: The enablers and barriers. Br. J. Nurs. 2015, 24, 833–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, P.; Catarino, F.; Duarte, C.; Matos, M.; Kolts, R.; Stubbs, J.; Ceresatto, L.; Duarte, J.; Pinto-Gouveia, J.; Basran, J. The development of compassionate engagement and action scales for self and others. J. Compassionate Health Care 2017, 4, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roze des Ordons, A.L.; MacIsaac, L.; Hui, J.; Everson, J.; Ellaway, R.H. Compassion in the clinical context: Constrained, distributed, and adaptive. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2020, 35, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadambi, S.; Loh, K.P.; Dunne, R.; Magnuson, A.; Maggiore, R.; Zittel, J.; Flannery, M.; Inglis, J.; Gilmore, N.; Mohamed, M.; et al. Older adults with cancer and their caregivers—Current landscape and future directions for clinical care. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 17, 742–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raeder, S. Highlights of the SIOG Annual Conference 2024. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2024, 5, 100667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolles, M.P.; Fort, M.P.; Glasgow, R.E. Aligning the planning, development, and implementation of complex interventions to local contexts with an equity focus: Application of the PRISM/RE-AIM framework. Int. J. Equity Health 2024, 23, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelton, R.C.; Chambers, D.A.; Glasgow, R.E. An extension of RE-AIM to enhance sustainability: Addressing dynamic context and promoting health equity over time. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradbury, H. The SAGE Handbook of Action Research; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potvin, L.; Di Ruggiero, E.; Shoveller, J.A. Pour une science des solutions: La recherche interventionnelle en santé des populations. LA Santé EN Action 2013, 425, 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- Potvin, L.; Ferron, C.; Terral, P.; Di Ruggiero, E.; Cervenka, I.; Foucaud, J. Recherche, partenariat, intervention: Le triptyque de la recherche interventionnelle en santé des populations. Glob. Health Promot. 2021, 28, 6–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.M. Action science revisited: Building knowledge out of practice to transform practice. In The Sage Handbook of Action Research, 3rd ed.; Bradbury, H., Ed.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2015; pp. 143–156. [Google Scholar]

- Amirkhani, A.; Papageorgiou, E.I.; Mohseni, A.; Mosavi, M.R. A review of fuzzy cognitive maps in medicine: Taxonomy, methods, and applications. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2017, 142, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersson, N.; Silver, H. Fuzzy cognitive mapping: An old tool with new uses in nursing research. J. Adv. Nurs. 2019, 75, 3823–3830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apostolopoulos, I.D.; Papandrianos, N.I.; Papathanasiou, N.D.; Papageorgiou, E.I. Fuzzy cognitive map applications in medicine over the last two decades: A review study. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarmiento, I.; Cockcroft, A.; Dion, A.; Belaid, L.; Silver, H.; Pizarro, K.; Pimentel, J.; Tratt, E.; Skerritt, L.; Ghadirian, M.Z.; et al. Fuzzy cognitive mapping in participatory research and decision making: A practice review. Arch. Public Health 2024, 82, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, G.; Longo, C.; Puzhko, S.; Gagnon, J.; Rahimzadeh, V. Deliberative stakeholder consultations: Creating insights into effective practice-change in family medicine. Fam. Pract. 2018, 35, 749–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, K.M.; Metersky, K. Reflective practice in nursing: A concept analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Knowl. 2022, 33, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J.; Thorogood, N. Qualitative Methods for Health Research, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2018; p. 420. [Google Scholar]

- Blacketer, M.P.; Brownlee, M.T.J.; Baldwin, E.D.; Bowen, B.B. Fuzzy cognitive maps of social-ecological complexity: Applying Mental Modeler to the Bonneville Salt Flats. Ecol. Complex. 2021, 47, 100950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knox, C.; Gray, S.; Zareei, M.; Wentworth, C.; Aminpour, P.; Wallace, R.V.; Hodbod, J.; Brugnone, N. Modeling complex problems by harnessing the collective intelligence of local experts: New approaches in fuzzy cognitive mapping. Collect. Intell. 2023, 2, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, S.A.; Zanre, E.; Gray, S.R. Fuzzy cognitive maps as representations of mental models and group beliefs. In Fuzzy Cognitive Maps for Applied Sciences and Engineering: From Fundamentals to Extensions and Learning Algorithms; Papageorgiou, E.I., Ed.; Intelligent Systems Reference Library; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 29–48. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, S.A.; Gray, S.; Cox, L.J.; Henly-Shepard, S. Mental Modeler: A fuzzy-logic cognitive mapping modeling tool for adaptive environmental management. In Proceedings of the 2013 46th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Wailea, HI, USA, 7 January 2013; pp. 965–973. [Google Scholar]

- Barbrook-Johnson, P.; Penn, A.S. Fuzzy cognitive mapping. In Systems Mapping: How to Build and Use Causal Models of Systems; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 79–95. [Google Scholar]

- Rostoft, S.; Seghers, N.; Hamaker, M.E. Achieving harmony in oncological geriatric assessment—Should we agree on a best set of tools? J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2023, 14, 101473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vélez, M.; Bain, T.; Rintjema, J.; Wilson, M.G. Rapid Synthesis: Identifying the Features and Impacts of Cancer-Care Networks on Enhancing Person-Centered Care and Access to Specialized Services; McMaster Health Forum: Hamilton, ON, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, L.W.; Townsend, J.S.; Rohan, E.A. Still lost in transition? Perspectives of ongoing cancer survivorship care needs from comprehensive cancer control programs, survivors, and health care providers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, G.; Qadan, M. Addressing fragmentation of care requires strengthening of health systems and cross-institutional collaboration. Cancer 2019, 125, 3296–3298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tremblay, D.; Touati, N.; Bilodeau, K.; Prady, C.; Usher, S.; Leblanc, Y.v. Risk-stratified pathways for cancer survivorship care: Insights from a deliberative multi-stakeholder consultation. Curr. Oncol. 2021, 28, 3408–3419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research; Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada; Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council. Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans—TCPS2 (2022). Available online: https://ethics.gc.ca/eng/policy-politique_tcps2-eptc2_2022.html (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Morgan, D.L. Planning Focus Groups; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowland, P.; Forest, P.-G.; Vanstone, M.; Leslie, M.; Abelson, J. Exploring meanings of expert and expertise in patient engagement activities: A qualitative analysis of a pan-Canadian survey. SSM-Qual. Res. Health 2023, 4, 100342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, K.; Tompson, M.; Hall, S.; Sattar, S.; Ahmed, S. Engaging older adults with cancer and their caregivers to set research priorities through cancer and aging research discussion sessions. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2021, 48, 613–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmiento, I.; Cockcroft, A.; Dion, A.; Paredes-Solís, S.; De Jesús-García, A.; Melendez, D.; Marie Chomat, A.; Zuluaga, G.; Meneses-Rentería, A.; Andersson, N. Combining conceptual frameworks on maternal health in indigenous communities—Fuzzy cognitive mapping using participant and operator-independent weighting. Field Methods 2022, 34, 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birt, L.; Scott, S.; Cavers, D.; Campbell, C.; Walter, F. Member checking: A tool to enhance trustworthiness or merely a nod to validation? Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 1802–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, S.; Hack, T.F.; Raffin-Bouchal, S.; McClement, S.; Stajduhar, K.; Singh, P.; Hagen, N.A.; Sinnarajah, A.; Chochinov, H.M. What are healthcare providers’ understandings and experiences of compassion? The healthcare compassion model: A grounded theory study of healthcare providers in Canada. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e019701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Report on Ageism; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Vogus, T.J.; McClelland, L.E.; Lee, Y.S.H.; McFadden, K.L.; Hu, X. Creating a compassion system to achieve efficiency and quality in health care delivery. J. Serv. Manag. 2021, 32, 560–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Union for International Cancer Control (UICC). What Is an Effective National Cancer Control Plan? Available online: https://www.uicc.org/news/what-effective-national-cancer-control-plan (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Haase, K.R.; Sattar, S.; Pilleron, S.; Lambrechts, Y.; Hannan, M.; Navarrete, E.; Kantilal, K.; Newton, L.; Kantilal, K.; Jin, R.; et al. A scoping review of ageism towards older adults in cancer care. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2023, 14, 101385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministère de la Santé et des Services Sociaux. Orientations Prioritaires 2023–2030 du Programme Québécois de Cancérologie. Available online: https://publications.msss.gouv.qc.ca/msss/document-003659/ (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Institut National du Cancer. Stratégie Décennale de Lutte Contre les Cancers 2021–2030: Des Progrès Pour Tous, de L’espoir Pour Demain. Available online: https://www.cancer.fr/l-institut-national-du-cancer/la-strategie-de-lutte-contre-les-cancers-en-france/strategie-decennale-de-lutte-contre-les-cancers-2021-2030 (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Cancer in Older Adults: Improving Access to Quality Care for an Aging World. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vUjB5AKy0Lk (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Hudson, B.; Hunter, D.; Peckham, S. Policy failure and the policy-implementation gap: Can policy support programs help? Policy Des. Pract. 2019, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Cancer Society. Advancing Health Equity Through Cancer Information and Support Services: Report on Communities That Are Underserved. Available online: https://cdn.cancer.ca/-/media/files/about-us/our-health-equity-work/underserved-communities-report_2023_en.pdf?rev=17ad3c41ed3b4b3abd99a33482b89d2a&hash=C8D25526630D310980C8B79DA73EB7D6 (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Tremblay, D.; Touati, N.; Roberge, D.; Breton, M.; Roch, G.; Denis, J.-L.; Candas, B.; Francoeur, D. Understanding cancer networks better to implement them more effectively: A mixed methods multi-case study. Implement. Sci. 2016, 11, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tremblay, D.; Usher, S.; Bilodeau, K.; Touati, N. The role of collaborative governance in translating national cancer programs into network-based practices: A longitudinal case study in Canada. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2025, 30, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chollette, V.; Weaver, S.J.; Huang, G.; Tsakraklides, S.; Tu, S.-P. Identifying cancer care team competencies to improve care coordination in multiteam systems: A modified Delphi study. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2020, 16, e1324–e1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoeven, D.C.; Chollette, V.; Lazzara, E.H.; Shuffler, M.L.; Osarogiagbon, R.U.; Weaver, S.J. The anatomy and physiology of teaming in cancer care delivery: A conceptual framework. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2020, 113, 360–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, H. “One of the team” patient experience of integrated breast cancer care. J. Integr. Care 2022, 30, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, G.; Berendsen, A.; Crawford, S.M.; Dommett, R.; Earle, C.; Emery, J.; Fahey, T.; Grassi, L.; Grunfeld, E.; Gupta, S.; et al. The expanding role of primary care in cancer control. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, 1231–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministère de la Santé et des Services Sociaux. les Personnes Touchées par le Cancer: Partenaires du Réseau de Cancérologie-Cadre de Référence. Available online: https://publications.msss.gouv.qc.ca/msss/document-001906/ (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Tremblay, D.; Touati, N.; Usher, S.; Bilodeau, K.; Pomey, M.P.; Levesque, L. Patient participation in cancer network governance: A six-year case study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bombard, Y.; Baker, G.R.; Orlando, E.; Fancott, C.; Bhatia, P.; Casalino, S.; Onate, K.; Denis, J.-L.; Pomey, M.-P. Engaging patients to improve quality of care: A systematic review. Implement. Sci. 2018, 13, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Torres, C.; Korc-Grodzicki, B.; Hsu, T. Models of clinical care delivery for geriatric oncology in Canada and the United States: A survey of geriatric oncology care providers. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2022, 13, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafaie, L.; Chanelière-Sauvant, A.-F.; Magné, N.; Bouleftour, W.; Tinquaut, F.; Célarier, T.; Bertoletti, L. Impact of medical specialties on diagnostic and therapeutic management of elderly cancer patients. Geriatrics 2023, 8, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, Z.; Patel, H.; Wijk, H.; Ekman, I.; Olaya-Contreras, P. A systematic review on implementation of person-centered care interventions for older people in out-of-hospital settings. Geriatr. Nurs. 2021, 42, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, S.; Hack, T.F.; MacInnis, C.C.; Jaggi, P.; Boss, H.; McClement, S.; Sinnarajah, A.; Thompson, G. Development and validation of a patient-reported measure of compassion in healthcare: The Sinclair Compassion Questionnaire (SCQ). BMJ Open 2021, 11, e045988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joannette, S. Signification Accordée à l’Approche Oncogériatrique Intégrée par des Personnes Agées Atteintes de Cancer. Master’s Thesis, Université de Sherbrooke, Longueuil, QC, Canada, 2016. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/11143/8190 (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Khoury, E.G.; Nuamek, T.; Heritage, S.; Fulton-Ward, T.; Kucharczak, J.; Ng, C.; Kalsi, T.; Gomes, F.; Lind, M.J.; Battisti, N.M.L.; et al. Geriatric oncology as an unmet workforce training need in the United Kingdom—A narrative review by the British Oncology Network for Undergraduate Societies (BONUS) and the International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) UK country group. Cancers 2023, 15, 4782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasovitsky, M.; Porter, I.; Tuch, G. The impact of ageism in the care of older adults with cancer. Curr. Opin. Support. Palliat. Care 2023, 17, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagan, S.H. Ageism in cancer care. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 2008, 24, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Federal/Provincial/Territorial Ministers Responsible for Seniors. Consultations on the Social and Economic Impacts of Ageism in Canada: “What We Heard” Report. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/corporate/seniors-forum-federal-provincial-territorial/reports/consultation-ageism-what-we-heard.html#h2.6 (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Van Herck, Y.; Feyaerts, A.; Alibhai, S.; Papamichael, D.; Decoster, L.; Lambrechts, Y.; Pinchuk, M.; Bechter, O.; Herrera-Caceres, J.; Bibeau, F.; et al. Is cancer biology different in older patients? Lancet Healthy Longev. 2021, 2, e663–e677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binstock, R.H. The oldest old: A fresh perspective or compassionate ageism revisited? Milbank Mem. Fund Q. Health Soc. 1985, 63, 420–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strohschein, F.J.; Newton, L.; Puts, M.; Jin, R.; Haase, K.; Plante, A.; Loucks, A.; Kenis, C.; Fitch, M. Optimiser les soins des adultes âgés atteints de cancer et l’accompagnement de leurs proches: Énoncé de position et contribution des infirmières canadiennes en oncologie. Can. Oncol. Nurs. J. 2021, 31, 357–362. [Google Scholar]

- Holtrop, J.S.; Estabrooks, P.A.; Gaglio, B.; Harden, S.M.; Kessler, R.S.; King, D.K.; Kwan, B.M.; Ory, M.G.; Rabin, B.A.; Shelton, R.C.; et al. Understanding and applying the RE-AIM framework: Clarifications and resources. J. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2021, 5, e126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nápoles, G.; Ranković, N.; Salgueiro, Y. On the interpretability of fuzzy cognitive maps. Knowl. Based Syst. 2023, 281, 111078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Mean (SD) | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 48.29 (12.74) | ||

| Gender | |||

| Woman | 45 | 84.91 | |

| Man | 8 | 15.09 | |

| Country | |||

| Canada | 47 | 88.68 | |

| France 1 | 6 | 11.32 | |

| Function 2 | |||

| Allied health professional 3 | 25 | 47.17 | |

| Oncologist | 5 | 9.43 | |

| Geriatrician | 4 | 7.55 | |

| Manager | 9 | 16.98 | |

| Director | 8 | 15.09 | |

| Researcher | 13 | 24.53 | |

| Policymaker | 8 | 15.09 | |

| Older adult with cancer 4 | 5 | 9.43 | |

| Experience in oncology (years) | |||

| Less than 3 | 16 | 30.19 | |

| 3 to 5 | 6 | 11.32 | |

| 5 to 10 | 11 | 20.75 | |

| More than 10 | 20 | 37.74 | |

| Institutional affiliation 5 | |||

| Health setting—academic mandate | 14 | 26.42 | |

| Health setting—community mandate | 28 | 52.83 | |

| Government 6 | 8 | 15.09 | |

| University | 4 | 7.55 | |

| Other | 1 | 1.89 |

| Centrality (C) 1 | Indegree | Outdegree | Perceived Relationship | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central concept | ||||

| Compassionate care of older adults with cancer | 19.71 | 19.71 | 0.00 | --- |

| Peripheral concepts | ||||

| National cancer programs | 15.32 | 8.00 | 7.32 | Positive |

| Effectiveness | 14.53 | 9.72 | 4.81 | Positive |

| Quality of care | 14.48 | 9.51 | 4.97 | Positive |

| Integrated network features | 11.81 | 6.31 | 5.50 | Positive |

| Being with | 11.50 | 5.00 | 6.50 | Positive |

| Teamwork | 10.55 | 6.35 | 4.20 | Positive |

| Person-centered care | 9.82 | 5.61 | 4.21 | Positive |

| Research gap | 9.61 | 4.36 | 5.25 | Negative |

| Fragmented care | 9.56 | 6.75 | 2.81 | Negative |

| Geriatric detection tools | 8.86 | 3.25 | 5.61 | Positive |

| Lack of dedicated financing | 7.85 | 2.50 | 5.35 | Negative |

| Specialized geriatric oncology clinics | 7.23 | 0.70 | 6.53 | Positive |

| Comprehensive geriatric assessment | 7.19 | 2.28 | 4.91 | Positive |

| Cancer care coordination | 7.01 | 3.31 | 3.70 | Positive |

| Patient partnership | 6.90 | 1.40 | 5.50 | Positive |

| Training | 5.74 | 0.45 | 5.29 | Positive |

| Communities of practice | 5.55 | 1.20 | 4.35 | Positive |

| Guideline to practice gap | 4.90 | 1.58 | 3.32 | Negative |

| Primary care | 4.81 | 1.31 | 3.50 | Positive |

| Prompt access to care | 4.75 | 2.25 | 2.50 | Positive |

| Lay caregiving | 4.68 | 2.80 | 1.88 | Positive |

| Reflective learning | 4.60 | 2.47 | 2.13 | Positive |

| Nonprofit community organizations | 4.03 | 0.78 | 3.25 | Positive |

| Equity, diversity, inclusion | 3.37 | 1.00 | 2.37 | Positive |

| Societal ageism | 2.83 | 1.00 | 1.83 | Negative |

| Policy to practice gap | 2.50 | 0.74 | 1.76 | Negative |

| Public awareness | 2.49 | 0.75 | 1.74 | Positive |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tremblay, D.; Russo, C.; Terret, C.; Prady, C.; Joannette, S.; Lessard, S.; Usher, S.; Pretet-Flamand, É.; Galvez, C.; Gélinas-Phaneuf, É.; et al. Exploring Determinants of Compassionate Cancer Care in Older Adults Using Fuzzy Cognitive Mapping. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 465. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32080465

Tremblay D, Russo C, Terret C, Prady C, Joannette S, Lessard S, Usher S, Pretet-Flamand É, Galvez C, Gélinas-Phaneuf É, et al. Exploring Determinants of Compassionate Cancer Care in Older Adults Using Fuzzy Cognitive Mapping. Current Oncology. 2025; 32(8):465. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32080465

Chicago/Turabian StyleTremblay, Dominique, Chiara Russo, Catherine Terret, Catherine Prady, Sonia Joannette, Sylvie Lessard, Susan Usher, Émilie Pretet-Flamand, Christelle Galvez, Élisa Gélinas-Phaneuf, and et al. 2025. "Exploring Determinants of Compassionate Cancer Care in Older Adults Using Fuzzy Cognitive Mapping" Current Oncology 32, no. 8: 465. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32080465

APA StyleTremblay, D., Russo, C., Terret, C., Prady, C., Joannette, S., Lessard, S., Usher, S., Pretet-Flamand, É., Galvez, C., Gélinas-Phaneuf, É., Terrier, J., & Moreau, N. (2025). Exploring Determinants of Compassionate Cancer Care in Older Adults Using Fuzzy Cognitive Mapping. Current Oncology, 32(8), 465. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32080465