Patient and Healthcare Professional Reflections on Consenting for Extra Bone Marrow Samples to a Biobank for Research—A Qualitative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- What are the experiences of patients, families, and caregivers regarding the current approach to consent for extra research-specific BM samples?

- (2)

- What are the experiences of healthcare professionals and research staff when approaching patients, families, and caregivers for consent for extra research-specific BM samples?

- (3)

- What factors influence patient, family, and caregiver decisions regarding whether to consent for extra research-specific BM samples?

- (4)

- What are the informational needs of patients, families, and caregivers regarding the consent process for extra research-specific BM samples?

- (5)

- How might the current approach to consent for extra research-specific BM samples be improved?

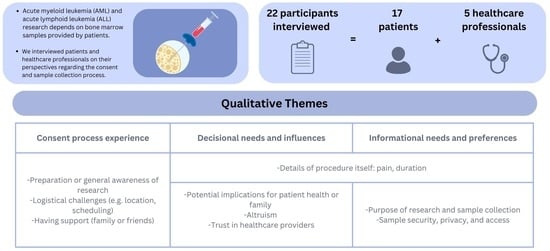

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample and Sampling Frame

2.2. Identification and Recruitment

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Patient and Public Involvement

3. Results

- Experiences of the consent process for research-specific BM donation

“[…] when it’s something so obvious that the research and the [HOSPITAL] are one and it’s not confronting, you don’t even have to make the decision of do I want to be part of it or not? Because it’s obvious… It was just, … for me it was something good because I even had more confidence in the [HOSPITAL] since they were doing research, they are at the very fine level of the knowledge and their field because they are doing research.”Patient, interviewee #13

“[…] for the BM rotations, it just depends how busy it is. Sometimes we’re not just doing BMs all day, like sometimes we’re helping out in the floor, maybe helping clinic. Like sometimes we’re pulled in different directions. So, if I had missed a consent for a biobank, it probably is because I was too rushed to take a look to see if they were supposed to get biobank or not, you know.”Staff, interviewee #3

“[…] we’re just thinking about us, and we want to get better and hopefully we’re going to live, right? So, I don’t think we’re really interested in, you know, some of the people might not be interested in the research part of it, cause it’s just another thing.”Patient, interviewee #11

- 2.

- Decisional needs and factors influencing patient, family, and caregiver decision-making

“If you’ve had a lot of asks on that day, you might have just run out of OK’s. But if you had nothing else asked of you that day, sure, why not? […] I would say also consider the patients state of being if they’re very weak and can’t think straight then either speak to their caregiver or maybe wait till they’re feeling better.”Patient, interviewee #2

“I can see if they caught me in a bad day I’d be like “no, not today, just not today. Come back, come back another day. The door is closed. Goodbye.”Patient interviewee #12

“I would say like once you’re poking around, might as well take a little bit more for research. No problem, but no, I wouldn’t have gone through that process twice if there was any way against it.”Patient, interviewee #18

“I think it gave me a bit of, I don’t know, like hope or goodness. In what I was going through and like obviously it’s not a great experience, but I kind of felt like I could help someone, even though I had to do this, I didn’t have to do it like just for nothing or not just for nothing to save my life, but like, I could like help something in the future.”Patient, interviewee #9

“Everybody was so good that it would be hard to say no to that team. When you’re sick, it’s different. You just want to do whatever you can for the people that are doing everything they can for you. So that’s the way I see it… So yeah, whenever you have a relationship like that with your healthcare professionals and you’ve asked them for so much when they ask back for one thing, you’re not going to say no. At least I’m not going to say no.”Patient, interviewee #2

- 3.

- Information needs and preferences

“About the research, I think like yeah, kind of having it, not necessarily all of it geared towards it, but like kind of showing what this sample can help with. And like what it can lead to or what it’s working on and stuff like how it’s contributing to better things I think would be a really neat thing to read as a patient, giving this sample kind of like I said, feeling like you’re a part of or doing something good.”Patient, interviewee #9

“[…] not too much information. Like if, a pamphlet could be good because it’s usually, it’s really like it’s only one page, so it’s really condensed information […] [It] could be good cause if you, if they told you so or explain you something. Hey, you going to miss it. And with a paper, maybe you’ll be able to read it when you’re going to be more disposed to.”Patient, interviewee #12

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Döhner, H.; Wei, A.H.; Appelbaum, F.R.; Craddock, C.; DiNardo, C.D.; Dombret, H.; Ebert, B.L.; Fenaux, P.; Godley, L.A.; Hasserjian, R.P.; et al. Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2022 recommendations from an international expert panel on behalf of the ELN. Blood 2022, 140, 1345–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, S.; Geng, X.; Korostyshevskiy, V.; Karp, J.E.; Lai, C. Systematic review and meta-analysis: Prognostic impact of time from diagnosis to treatment in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer 2023, 129, 2975–2985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venugopal, S.; Sekeres, M.A. Contemporary Management of Acute Myeloid Leukemia: A Review. JAMA Oncol. 2024, 10, 1417–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatia, K.; Sandhu, V.; Wong, M.H.; Iyer, P.; Bhatt, S. Therapeutic biomarkers in acute myeloid leukemia: Functional and genomic approaches. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1275251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, S.; Oh, T.S.; Platanias, L.C. Role of Biomarkers in the Management of Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maganti, H.B.; Jrade, H.; Cafariello, C.; Rothberg, J.L.M.; Porter, C.J.; Yockell-Lelièvre, J.; Battaion, H.L.; Khan, S.T.; Howard, J.P.; Li, Y.; et al. Targeting the MTF2–MDM2 axis sensitizes refractory acute myeloid leukemia to chemotherapy. Cancer Discov. 2018, 8, 1376–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snapes, E.; De Wilde, A.; Carpenter, J.; Schacter, B.; Simeon-Dubach, D.; Tarling, T.; Arant, C.; Bledsoe, M.; Standard, E.; Watson, P.; et al. Best Practices: Recommendations for Repositories, 5th ed.; ISBER: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, C.C.; Martin, B.R.; Asa, S.L. Defining diagnostic tissue in the era of personalized medicine. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2013, 185, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, C.C.; Torlakovic, E.E.; Porwit, A. The role of diagnostic tissue in research. Pathobiology 2014, 81, 298–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, S.; Fleming, J.; Shepherd, H.L.; Walczak, A.; Clark, J.; Butow, P. “As Long as You Ask”: A Qualitative Study of Biobanking Consent-Oncology Patients’ and Health Care Professionals’ Attitudes, Motivations, and Experiences-the B-PPAE Study. Oncologist 2019, 24, 844–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoefel, L.; O’Connor, A.M.; Lewis, K.B.; Boland, L.; Sikora, L.; Hu, J.; Stacey, D. 20th Anniversary Update of the Ottawa Decision Support Framework Part 1: A Systematic Review of the Decisional Needs of People Making Health or Social Decisions. Med. Decis. Mak. 2020, 40, 555–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, B.C.; Harris, I.B.; Beckman, T.J.; Reed, D.A.; Cook, D.A. Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Acad. Med. 2014, 89, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger, R.A.; Casey, M.A. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. Naturalistic Inquiry; Sage: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Bowling, A. Research Methods in Health. In Investigating Health and Health Services, 2nd ed.; Open University Press: Maidenhead, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- NVivo: Leading Qualitative Data Analysis Software (QDAS) by Lumivero n.d. Available online: https://lumivero.com/products/nvivo/ (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Toward good practice in thematic analysis: Avoiding common problems and be(com)ing a knowing researcher. Int. J. Transgend. Health 2022, 24, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V.; Terry, G.; Hayfield, N. Thematic Analysis. In Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences; Springer: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, A.M.; Allen, J.; Zeps, N.; Pienaar, C.; Bulsara, C.; Monterosso, L. Consent to Donate Surgical Biospecimens for Research: Perceptions of People with Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2016, 39, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, K.L.; Tsark, J.U.; Powers, A.; Croom, K.; Kim, R.; Gachupin, F.C.; Morris, P. Cancer patient perceptions about biobanking and preferred timing of consent. Biopreserv. Biobank 2014, 12, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, J.; Pellegrini, I.; Viret, F.; Vey, N.; Daufresne, L.M.; Chabannon, C.; Julian-Reynier, C. Consent for biobanking: Assessing the understanding and views of cancer patients. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2011, 103, 154–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fradgley, E.A.; Chong, S.E.; Cox, M.E.; Paul, C.L.; Gedye, C. Enlisting the willing: A study of healthcare professional-initiated and opt-in biobanking consent reveals improvement opportunities throughout the registration process. Eur. J. Cancer 2018, 89, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaphingst, K.A.; Janoff, J.M.; Harris, L.N.; Emmons, K.M. Views of female breast cancer patients who donated biologic samples regarding storage and use of samples for genetic research. Clin. Genet. 2006, 69, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, I.; Chabannon, C.; Mancini, J.; Viret, F.; Vey, N.; Julian-Reynier, C. Contributing to research via biobanks: What it means to cancer patients. Health Expect. 2014, 17, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domaradzki, J.; Czekajewska, J.; Walkowiak, D. Attitudes of oncology patients’ towards biospecimen donation for biobank research. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unger, J.M.; Vaidya, R.; Hershman, D.L.; Minasian, L.M.; Fleury, M.E. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Magnitude of Structural, Clinical, and Physician and Patient Barriers to Cancer Clinical Trial Participation. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2019, 111, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deans, K.J.; Sabihi, S.; Forrest, C.B. Learning health systems. Semin. Pediatr. Surg. 2018, 27, 375–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domaradzki, J.; Pawlikowski, J. Public Attitudes toward Biobanking of Human Biological Material for Research Purposes: A Literature Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, T.R. The Gift Relationship: From Human Blood to Social Policy; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Axler, R.E.; Irvine, R.; Lipworth, W.; Morrell, B.; Kerridge, I.H. Why might people donate tissue for cancer research? Insights from organ/tissue/blood donation and clinical research. Pathobiology 2008, 75, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dive, L.; Critchley, C.; Otlowski, M.; Mason, P.; Wiersma, M.; Light, E.; Stewart, C.; Kerridge, I.; Lipworth, W. Public trust and global biobank networks. BMC Med. Ethics 2020, 21, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sex (male) | 11 | 65 |

| Sample in the biobank? | ||

| Yes | 14 | 82% |

| No | 3 | 18% |

| Reason for not being in biobank | ||

| Declined | 1 | |

| Not asked | 1 | |

| Hesitant (provided a sample at relapse) | 1 | |

| Diagnosis | ||

| AML | 9 | 53% |

| ALL | 8 | 47% |

| Median age at diagnosis (years) [range] | 56 [19–68] | |

| White count at diagnosis (×109/L) [range] | 20.3 [1.3–109.7] |

| Level of Change | Areas of Change |

|---|---|

| Hospital level | Increase awareness that research occurs as part of healthcare and that one may be asked to participate in research while attending hospital. Develop appropriate systems to minimise risk of missing opportunities to approach patients who may be eligible to donate to the biobank. |

| Trained personnel | Identify appropriate team members to approach patients and develop training to minimise the risk of coercion. Develop training for team members who are obtaining consent for the samples to ensure they are knowledgeable about the biobank (including structure and uses). Provide clear documentation of the process and about the biobank and which may be retained for future reference by the patient and family members. |

| Support | Identify opportunities to introduce biobank donation as early as possible to provide the patient and/or family time to digest the material Identify opportunities to allow family or friends to be present to help the patient process the information during a time of information overload. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nicholls, S.G.; Camilleri, E.; Chesser, T.; Davis, G.; Godard, K.; Fox, G.; Gordon, M.J.; Lewis, K.B.; Lepage, J.; Motalo, O.; et al. Patient and Healthcare Professional Reflections on Consenting for Extra Bone Marrow Samples to a Biobank for Research—A Qualitative Study. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 179. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32030179

Nicholls SG, Camilleri E, Chesser T, Davis G, Godard K, Fox G, Gordon MJ, Lewis KB, Lepage J, Motalo O, et al. Patient and Healthcare Professional Reflections on Consenting for Extra Bone Marrow Samples to a Biobank for Research—A Qualitative Study. Current Oncology. 2025; 32(3):179. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32030179

Chicago/Turabian StyleNicholls, Stuart G., Erika Camilleri, Taryn Chesser, Gary Davis, Katya Godard, Grace Fox, Madeleine Jane Gordon, Krystina B. Lewis, Jocelyn Lepage, Oksana Motalo, and et al. 2025. "Patient and Healthcare Professional Reflections on Consenting for Extra Bone Marrow Samples to a Biobank for Research—A Qualitative Study" Current Oncology 32, no. 3: 179. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32030179

APA StyleNicholls, S. G., Camilleri, E., Chesser, T., Davis, G., Godard, K., Fox, G., Gordon, M. J., Lewis, K. B., Lepage, J., Motalo, O., Nuttall, W., Peleshok, C., Ito, C. Y., Villeneuve, P. J. A., & Sabloff, M. (2025). Patient and Healthcare Professional Reflections on Consenting for Extra Bone Marrow Samples to a Biobank for Research—A Qualitative Study. Current Oncology, 32(3), 179. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32030179