The Cancer and Work Scale (CAWSE): Assessing Return to Work Likelihood and Employment Sustainability After Cancer

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Factors Associated with Sustained Employment and RTW in ITBC

1.3. Study Purpose

1.4. Ethics Statement

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study I—Participants of the Content Validation Procedures of Item Development and Content Validation

2.2. Study I—Participants of the Content Validation

2.2.1. Study I—Variables and Measures

2.2.2. Study I—Analysis Plan

2.3. Study II: Validation, Expansion and Application of the CAWSE Design and Development

2.3.1. Study II—Participants

2.3.2. Study II—Variables and Measures

2.4. Study II—Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study I—Demographics

3.2. Study I—Content Validity: Scale Development

3.3. Study II—Demographics

3.4. Study II—Internal Structure and Quality Assessment

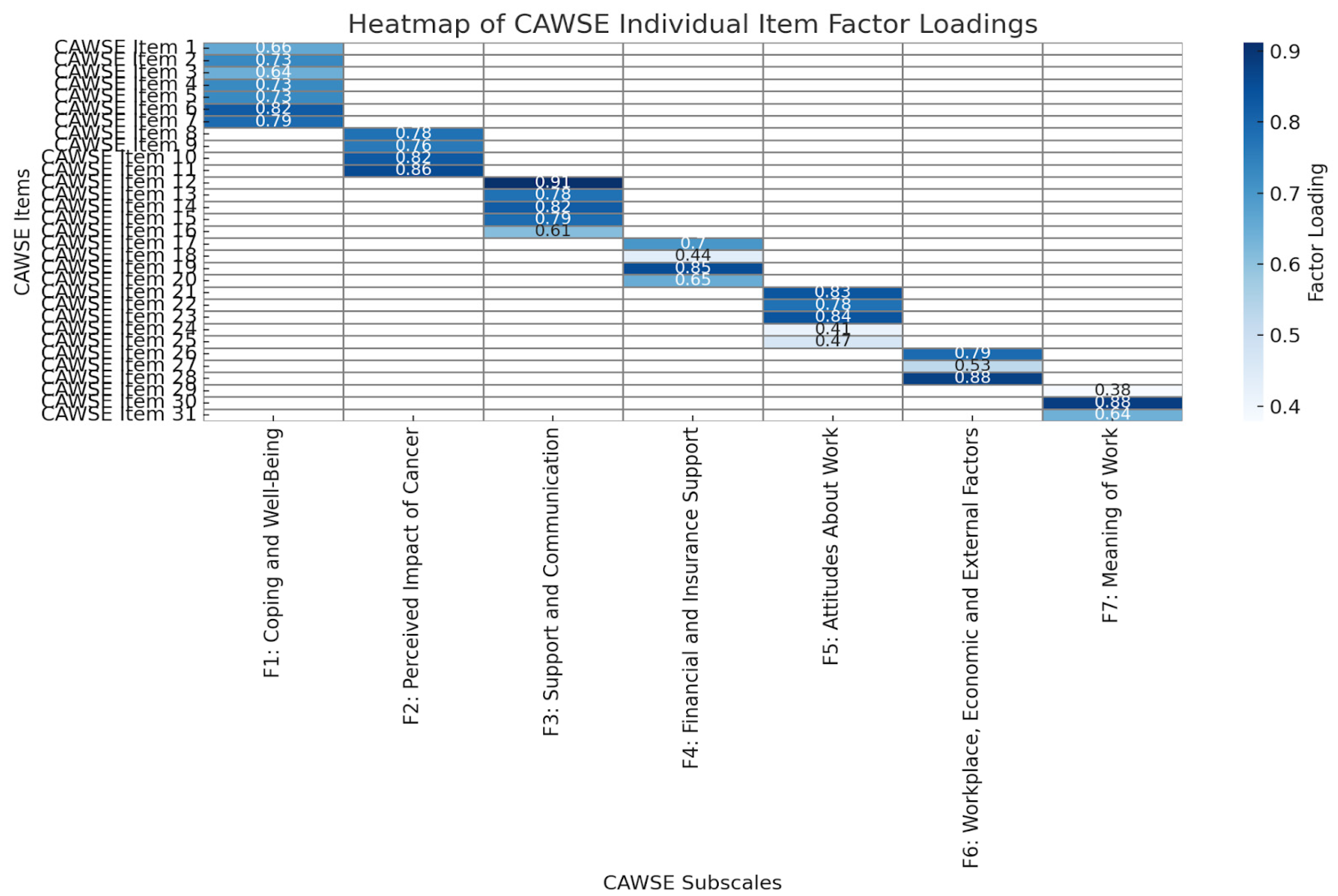

3.4.1. Structural Validity

3.4.2. Internal Consistency

3.4.3. Cross-Cultural Validity

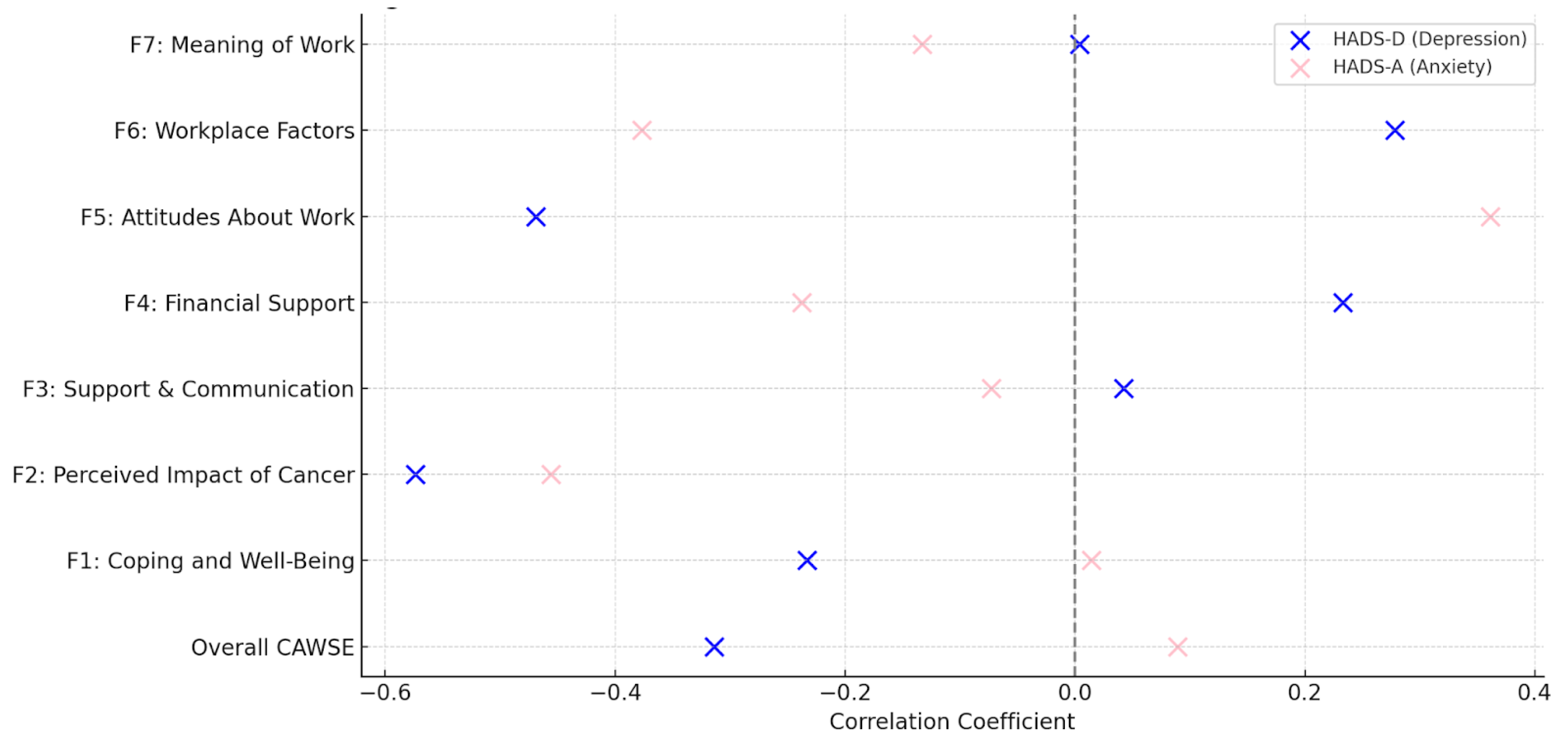

3.4.4. Hypothesis Testing for Construct Validity

3.4.5. Scale Quality: Convergent, Concurrent and Divergent Validity

3.4.6. Assessment of CAWSE Responsiveness

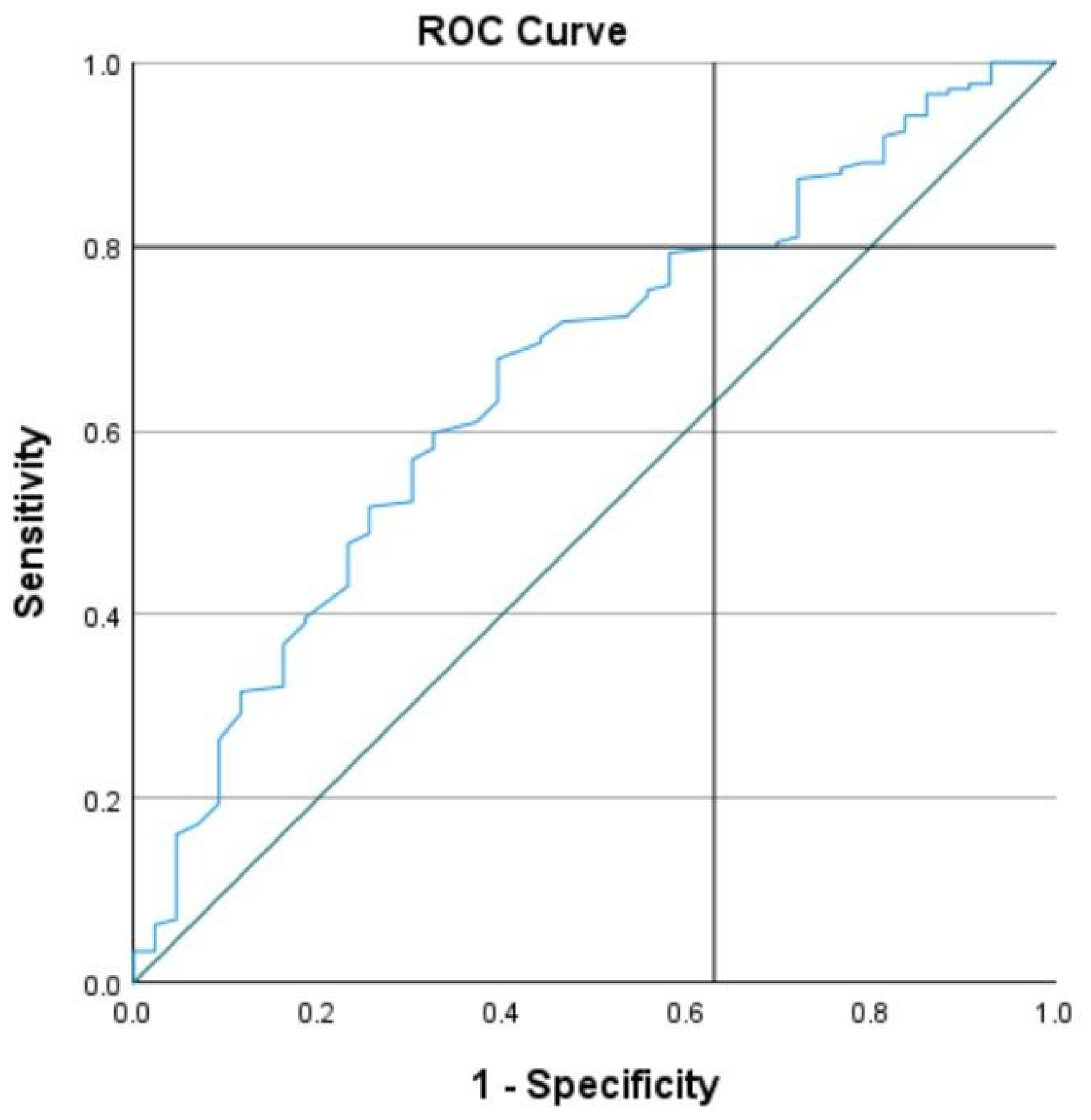

3.4.7. Criterion Validity

4. Discussion

4.1. Structural and Construct Validity

4.2. Responsiveness

4.3. The Need for CAWSE in Cancer-Specific RTW Assessments

4.4. CAWSE as a Dual-Purpose Tool for Assessing RTW and Employment Sustainability

4.5. Comparison of CAWSE with Existing RTW Assessment Tools

4.6. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CAWSE | Cancer and Work Scale |

| RTW | Return to Work |

| ITBC | Individuals Touched by Cancer |

| EFA | Exploratory Factor Analysis |

| CFA | Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| HRQoL | Health-Related Quality of Life |

| COSMIN | Consensus-Based Standards for the Selection of Health Measurement Instruments |

| HADS | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale |

| EORTC QLQ-C30 | European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire |

References

- Butow, P.; Laidsaar-Powell, R.; Konings, S.; Lim, C.Y.S.; Koczwara, B. Return to work after a cancer diagnosis: A meta-review of reviews and a meta-synthesis of recent qualitative studies. J. Cancer Surviv. 2020, 14, 114–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markovic, C.; Mackenzie, L.; Lewis, J.; Singh, M. Working with cancer: A pilot study of work participation among cancer survivors in Western Sydney. Aust. Occup. Ther. J. 2020, 67, 592–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkinson, M.; Maheu, C. Cancer and Work. Can. Oncol. Nurs. J./Rev. Can. Soins Infirm. Oncol. 2019, 29, 258–266. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, D.; Kearney, T.; Donnelly, D.W.; Downing, A.; Wright, P.; Wilding, S.; Wagland, R.; Watson, E.; Glaser, A.; Gavin, A. Factors influencing job loss and early retirement in working men with prostate cancer—Findings from the population-based Life After Prostate Cancer Diagnosis (LAPCD) study. J. Cancer Surviv. 2018, 12, 669–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tracy, J.K.; Falk, D.; Thompson, R.J.; Scheindlin, L.; Adetunji, F.; Swanberg, J.E. Managing the cancer–work interface: The effect of cancer survivorship on unemployment. Cancer Manag. Res. 2018, 10, 6479–6487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehnert, A. Employment and work-related issues in cancer survivors. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2011, 77, 109–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Boer, A.G.E.M.; Taskila, T.; Ojajärvi, A.; van Dijk, F.J.H.; Verbeek, J.H.A.M. Cancer survivors and unemployment: A meta-analysis and meta-regression. JAMA 2009, 301, 753–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwekkeboom, K.L. Cancer Symptom Cluster Management. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 2016, 32, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brouwer, S.; Amick, B.C.; Lee, H.; Franche, R.-L.; Hogg-Johnson, S. The Predictive Validity of the Return-to-Work Self-Efficacy Scale for Return-to-Work Outcomes in Claimants with Musculoskeletal Disorders. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2015, 25, 725–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, D.; Amick, B.C.; Rogers, W.H.; Malspeis, S.; Bungay, K.; Cynn, D. The Work Limitations Questionnaire. Med. Care 2001, 39, 72–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greidanus, M.A.; de Boer, A.G.E.M.; de Rijk, A.E.; Brouwers, S.; de Reijke, T.M.; Kersten, M.J.; Klinkenbijl, J.H.G.; Lalisang, R.I.; Lindeboom, R.; Zondervan, P.J.; et al. The Successful Return-To-Work Questionnaire for Cancer Survivors (I-RTW_CS): Development, Validity and Reproducibility. Patient 2020, 13, 567–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franche, R.-L.; Corbière, M.; Lee, H.; Breslin, F.C.; Hepburn, C.G. The Readiness for Return-To-Work (RRTW) scale: Development and validation of a self-report staging scale in lost-time claimants with musculoskeletal disorders. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2007, 17, 450–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbière, M.; Negrini, A.; Durand, M.-J.; St-Arnaud, L.; Briand, C.; Fassier, J.-B.; Loisel, P.; Lachance, J.-P. Development of the Return-to-Work Obstacles and Self-Efficacy Scale (ROSES) and Validation with Workers Suffering from a Common Mental Disorder or Musculoskeletal Disorder. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2017, 27, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coenen, P.; Zegers, A.D.; de Stapelfeldt, C.M.; Maaker-Berkhof, M.; van der Abma, F.; Beek, A.J.; Bültmann, U.; Duijts, S.F.A. Cross-cultural translation and adaptation of the Readiness for Return To Work questionnaire for Dutch cancer survivors. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2021, 30, e13383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Jong, M.; Tamminga, S.J.; de Boer, A.G.E.M.; Frings-Dresen, M.H.W. Quality of working life of cancer survivors: Development of a cancer-specific questionnaire. J. Cancer Surviv. 2016, 10, 394–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheu, C.; Parkinson, M.; Wong, C.; Yashmin, F.; Longpré, C. Self-Employed Canadians’ Experiences with Cancer and Work: A Qualitative Study. Curr. Oncol. 2023, 30, 4586–4602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Boer, A.G.; Taskila, T.K.; Tamminga, S.J.; Feuerstein, M.; Frings-Dresen, M.H.; Verbeek, J.H. Interventions to enhance return-to-work for cancer patients. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 2015, CD007569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosbjerg, R.; Hansen, D.G.; Zachariae, R.; Hoejris, I.; Lund, T.; Labriola, M. The Predictive Value of Return to Work Self-efficacy for Return to Work Among Employees with Cancer Undergoing Chemotherapy. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2020, 30, 665–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamminga, S.J.; van Hezel, S.; de Boer, A.G.; Frings-Dresen, M.H. Enhancing the Return to Work of Cancer Survivors: Development and Feasibility of the Nurse-Led eHealth Intervention Cancer@Work. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2016, 5, e118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catt, S.; Starkings, R.; Shilling, V.; Fallowfield, L. Patient-reported outcome measures of the impact of cancer on patients’ everyday lives: A systematic review. J. Cancer Surviv. 2017, 11, 211–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laidsaar-Powell, R.; Konings, S.; Rankin, N.; Koczwara, B.; Kemp, E.; Mazariego, C.; Butow, P. A meta-review of qualitative research on adult cancer survivors: Current strengths and evidence gaps. J. Cancer Surviv. 2019, 13, 852–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheu, C.; Parkinson, M.; Oldfield, M.; Kita-Stergiou, M.; Bernstein, L.; Esplen, M.J.; Hernandez, C.; Zanchetta, M.; Singh, M.; on behalf of the Cancer and Work core team members. Cancer and Work. 2016. Available online: https://www.cancerandwork.ca/ (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Nitkin, P.; Parkinson, M.; Schultz, I.Z.; Cancer and Work—A Canadian Perspective. Canadian Association of Psychological Oncology. 2011. Available online: https://www.cancerandwork.ca/cancer-and-work-a-canadian-perspective/ (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Maheu, C.; Parkinson, M.; Johnson, K.; Singh, M.; Dolgoy, N.; Stockdale, C.; Dupuis, S.-P.; Tock, W.L. Work ability and quality of life outcomes of cancer survivor participants from a vocational rehabilitation-led return to work pilot intervention. Ingram School of Nursing. Infographics derived from the Nursing master’s thesis work. McGill J. Med. 2023, 21. Available online: https://mjm.mcgill.ca/article/view/1074 (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Jette, A.M. Toward a Common Language for Function, Disability, and Health: ICF. World Health Organization. Phys. Ther. 2006, 86, 726–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokkink, L.B.; de Vet, H.C.W.; Prinsen, C.A.C.; Patrick, D.L.; Alonso, J.; Bouter, L.M.; Terwee, C.B. COSMIN Risk of Bias checklist for systematic reviews of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures. Qual. Life Res. 2018, 27, 1171–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokkink, L.B.; Terwee, C.B.; Knol, D.L.; Stratford, P.W.; Alonso, J.; Patrick, D.L.; Bouter, L.M.; de Vet, H.C. The COSMIN checklist for evaluating the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties: A clarification of its content. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2010, 10, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mokkink, L.B.; Terwee, C.B.; Patrick, D.L.; Alonso, J.; Stratford, P.W.; Knol, D.L.; Bouter, L.M.; de Vet, H.C. The COSMIN study reached international consensus on taxonomy, terminology, and definitions of measurement properties for health-related patient-reported outcomes. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2010, 63, 737–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prinsen, C.A.C.; Mokkink, L.B.; Bouter, L.M.; Alonso, J.; Patrick, D.L.; de Vet, H.C.W.; Terwee, C.B. COSMIN guideline for systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures. Qual. Life Res. 2018, 27, 1147–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Vet, H.C.W.; Terwee, C.B.; Mokkink, L.B.; Knol, D.L. Development of a measurement instrument. In Measurement in Medicine: A Practical Guide; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011; pp. 30–64. [Google Scholar]

- Terwee, C.B.; Prinsen, C.A.C.; Chiarotto, A.; Westerman, M.J.; Patrick, D.L.; Alonso, J.; Bouter, L.M.; de Vet, H.C.W.; Mokkink, L.B. COSMIN methodology for evaluating the content validity of patient-reported outcome measures: A Delphi study. Qual. Life Res. 2018, 27, 1159–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linden, W.; Vodermaier, A.A.; McKenzie, R.; Barroetavena, M.C.; Yi, D.; Doll, R. The Psychosocial Screen for Cancer (PSSCAN): Further validation and normative data. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2009, 7, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linden, W.; Yi, D.; Barroetavena, M.C.; MacKenzie, R.; Doll, R. Development and validation of a psychosocial screening instrument for cancer. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2005, 3, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, J.E.; Sherbourne, C.D. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med. Care 1992, 30, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gotay, C.C.; Pagano, I.S. Assessment of Survivor Concerns (ASC): A newly proposed brief questionnaire. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2007, 5, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zigmond, A.S.; Snaith, R.P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1983, 67, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vodermaier, A.; Linden, W.; Siu, C. Screening for emotional distress in cancer patients: A systematic review of assessment instruments. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2009, 101, 1464–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aaronson, N.K.; Ahmedzai, S.; Bergman, B.; Bullinger, M.; Cull, A.; Duez, N.J.; Filiberti, A.; Flechtner, H.; Fleishman, S.B.; De Haes, J.C.J.M.; et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: A Quality-of-Life Instrument for Use in International Clinical Trials in Oncology. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1993, 85, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayers, P.M. Interpreting quality of life data: Population-based reference data for the EORTC QLQ-C30. Eur. J. Cancer 2001, 37, 1331–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mock, V.; Atkinson, A.; Barsevick, A.; Cella, D.; Cimprich, B.; Cleeland, C.; Donnelly, J.; Eisenberger, M.A.; Escalante, C.; Hinds, P.; et al. NCCN Practice Guidelines for Cancer-Related Fatigue. Oncology 2000, 14, 151–161. [Google Scholar]

- Borneman, T.; Piper, B.F.; Sun, V.C.-Y.; Koczywas, M.; Uman, G.; Ferrell, B. Implementing the fatigue guidelines at one NCCN member institution: Process and outcomes. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2007, 5, 1092–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanley, J.A.; McNeil, B.J. The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology 1982, 143, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Schouw, Y.T.; Straatman, H.; Verbeek, A.L. ROC curves and the areas under them for dichotomized tests: Empirical findings for logistically and normally distributed diagnostic test results. Med. Decis. Mak. 1994, 14, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takenouchi, T.; Komori, O.; Eguchi, S. An extension of the receiver operating characteristic curve and AUC-optimal classification. Neural Comput. 2012, 24, 2789–2824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartlett, M.S. Tests of significance in factor analysis. Br. J. Stat. Psychol. 1950, 3, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkansah, B.K. On the Kaiser-Meier-Olkin’s Measure of Sampling Adequacy. Math. Theory Model. 2018, 8, 52–76. [Google Scholar]

- Halpern, M.T.; de Moor, J.S.; Han, X.; Zhao, J.; Zheng, Z.; Yabroff, K.R. Association of Employment Disruptions and Financial Hardship Among Individuals Diagnosed with Cancer in the United States: Findings from a Nationally Representative Study. Cancer Res. Commun. 2023, 3, 1830–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorland, H.F.; Abma, F.I.; Van Zon, S.K.R.; Stewart, R.E.; Amick, B.C.; Ranchor, A.V.; Roelen, C.A.M.; Bültmann, U. Fatigue and depressive symptoms improve but remain negatively related to work functioning over 18 months after return to work in cancer patients. J. Cancer Surviv. 2018, 12, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorland, H.F.; Abma, F.I.; Roelen, C.A.M.; Stewart, R.E.; Amick, B.C.; Ranchor, A.V.; Bültmann, U. Work functioning trajectories in cancer patients: Results from the longitudinal Work Life after Cancer (WOLICA) study. Int. J. Cancer 2017, 141, 1751–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, J. Factors associated with the quality of work life among working breast cancer survivors. Asia-Pac. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2022, 9, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlin, P.; von Blanckenburg, P. Death anxiety as general factor to fear of cancer recurrence. Psycho-Oncology 2022, 31, 1527–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorland, H.F.; Abma, F.I.; Roelen, C.A.M.; Smink, J.G.; Ranchor, A.V.; Bültmann, U. Factors influencing work functioning after cancer diagnosis: A focus group study with cancer survivors and occupational health professionals. Support. Care Cancer 2016, 24, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duijts, S.F.A.; Kieffer, J.M.; van Muijen, P.; van der Beek, A.J. Sustained employability and health-related quality of life in cancer survivors up to four years after diagnosis. Acta Oncol. 2017, 56, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dyk, K.; Ganz, P.A. Cancer-Related Cognitive Impairment in Patients with a History of Breast Cancer. JAMA 2021, 326, 1736–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rath, H.M.; Steimann, M.; Ullrich, A.; Rotsch, M.; Zurborn, K.-H.; Koch, U.; Kriston, L.; Bergelt, C. Psychometric properties of the Occupational Stress and Coping Inventory (AVEM) in a cancer population. Acta Oncol. 2015, 54, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.-J.; Xue, P.; Gu, W.-W.; Su, X.-Q.; Li, J.-M.; Kuai, B.-X.; Xu, J.-S.; Xie, H.-W.; Han, P.-P. Development and validation of Adaptability to Return-to-Work Scale (ARTWS) for cancer patients. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1275331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mokkink, L.B.; Terwee, C.B.; Patrick, D.L.; Alonso, J.; Stratford, P.W.; Knol, D.L.; Bouter, L.M.; de Vet, H.C.W. The COSMIN checklist for assessing the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties of health status measurement instruments: An international Delphi study. Qual. Life Res. 2010, 19, 539–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boateng, G.O.; Neilands, T.B.; Frongillo, E.A.; Melgar-Quiñonez, H.R.; Young, S.L. Best Practices for Developing and Validating Scales for Health, Social, and Behavioral Research: A primer. Front. Public Health 2018, 6, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Aim | Input | Decision | Output | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study I: Content Validity | ||||

| 1. PROM Development: Item Generation | ||||

| Build items that explore: Symptoms Workplace accommodations Return to work as a coping strategy Meaning of work Financial factors | Expert focus group assessment of the literature and formulation of initial items (n.b.: Expert group includes patient-partners). |

| Preliminary version of CAWSE 16 items on a 7-point Likert scale (range 0–6) |

| 2. Content Validity | ||||

| Content Validity Testing of the Preliminary Version of CAWSE with 130 participants | ||||

| Preliminary version of the 16-item CAWSE with newly diagnosed cancer patients of less than 12 months. Study I survey completed by 438 ITBC of which 276 (63%) were 65 or younger, and of these, 130 were working prior to cancer diagnosis. | Test the provisional scale by evaluating patient responses, followed by a statistical analysis to systematically identify and select pertinent items for the final scale. | A second focus group with the initial five experts was held to review the factor loading of the 16-item CAWSE. | Following factor analysis, one item was removed due to low factor loading. Additionally, new items were created to improve alignment with the four-factor vocational rehabilitation model for individuals living with cancer. Hence, 28 new items were added to the 15 initial items. | Factor loading of the initial 16 items resulted in five subscales:

Cronbach alpha: Factor Analysis Symptoms: 0.85 Accommodation: 0.77 Meaning of work: 0.71 Coping: 0.66 Importance of work: 0.38 Variance: 68.55% Final version of the PROM CAWSE with 43 items. |

| Study II: Testing the final version of the questionnaire with a new population | ||||

| 3 to 10. Evaluation of the Internal Structure and Other Measurement Properties According to COSMIN | ||||

| Assessment of the 43 items CAWSE on its validity, reliability, and responsiveness. Study II survey completion by 216 ITBC | Test the psychometric properties of the CAWSE 43 items. | Based on the highest factor loadings observed in the data analysis, the 43 items were categorized into six factors. | Internal Structure Validation

| |

| n | % | Valid Percent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Birth country (n = 189) | |||

| Canada | 155 | 71.4 | 82.0 |

| Other | 34 | 15.7 | 18.0 |

| Ethnicity (n = 189) | |||

| White | 151 | 69.6 | 79.9 |

| Black | 5 | 2.3 | 2.6 |

| Asian | 12 | 5.5 | 6.3 |

| East Indian | 5 | 2.3 | 2.6 |

| Jewish | 6 | 2.8 | 3.2 |

| Other | 10 | 4.6 | 5.3 |

| First language (n = 189) | |||

| English | 158 | 72.8 | 83.6 |

| French | 6 | 2.8 | 3.2 |

| Other | 25 | 11.5 | 13.2 |

| Highest Education Level (n = 189) | |||

| High school | 12 | 5.5 | 6.3 |

| College | 100 | 46.1 | 52.9 |

| University | 74 | 34.1 | 39.2 |

| Other | 3 | 1.4 | 1.6 |

| Relationship status (n = 189) | |||

| Single/Separated/Divorced/Widowed | 57 | 26.3 | 30.2 |

| Married/Living with a partner | 132 | 60.8 | 69.8 |

| Total Household income (n = 187) | |||

| <40,000$ | 28 | 12.9 | 15.0 |

| 40,000$–80,000$ | 45 | 20.7 | 24.1 |

| >80,000$ | 114 | 52.5 | 61.0 |

| Type of cancer (n = 181) | |||

| Breast | 80 | 36.9 | 44.2 |

| Hodgkin’s Lymphoma/Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma | 16 | 7.4 | 8.8 |

| Gynecological | 11 | 5.1 | 6.1 |

| Prostate and testicular | 12 | 5.5 | 6.6 |

| Thyroid | 6 | 2.8 | 3.3 |

| Kidney | 5 | 2.3 | 2.8 |

| Melanoma (3)/Other (48) | 51 | 23.5 | 28.2 |

| Metastasis diagnosis (n = 176) | |||

| Yes | 32 | 14.7 | 18.2 |

| No | 144 | 66.4 | 81.8 |

| Cancer treatment (n = 180) | |||

| Only received chemotherapy or radiation or adjuvant therapy | 42 | 19.4 | 23.3 |

| Combination of chemotherapy and/or radiation and/or adjuvant therapy with (84.4%) or without surgery (15.6%) | 138 | 63.6 | 76.7 |

| Returned to work after diagnosis (n = 217) | |||

| Yes | 174 | 80.2 | 80.2 |

| No | 43 | 19.8 | 19.8 |

| Change in position following return to work (n = 163) | |||

| Yes | 62 | 28.6 | 38.0 |

| No | 101 | 46.5 | 62.0 |

| Type of work prior to cancer diagnosis (n = 214) | |||

| Full-time | 173 | 79.7 | 80.8 |

| Part-time | 23 | 10.6 | 10.7 |

| Homemaker (3)/Retired (1) | 4 | 1.8 | 1.9 |

| Working/Student full-time | 12 | 5.5 | 5.6 |

| Sick Leave or Disability | 2 | 0.9 | 0.9 |

| Subscale | Explained Variance | Cronbach’s Alpha | Cohen’s D |

|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1: Coping and Well-Being at Work | 22.42% | 0.899 | 0.34 |

| Factor 2: Perceived Impact of Cancer on Work | 15.15% | 0.845 | 0.22 |

| Factor 3: Support, Communication, and Accommodations at Work | 8.53% | 0.867 | 0.23 |

| Factor 4: Financial and Insurance Support | 5.21% | 0.720 | 0.29 |

| Factor 5: Attitudes about Work | 6.19% | 0.803 | 0.66 |

| Factor 6: Workplace, Economic and External Factors | 4.91% | 0.619 | 0.03 |

| Factor 7: Meaning of Work | 4.02% | 0.729 | 0.96 |

| Total Scale | 66.45% | 0.787 | 0.62 |

| Cut-Off Range | Sensitivity (%) | 1-Specificity (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 99.5 vs. 100.5 | 89.7 | 18.6 |

| 101.5 vs. 102.5 | 89.1 | 23.3 |

| 104.5 vs. 106.5 | 87.9 | 27.9 |

| 108.5 vs. 110.5 | 85.1 | 27.9 |

| 112.5 vs. 115.0 | 83.3 | 27.9 |

| 117.0 vs. 118.5 | 81.6 | 27.9 |

| 120.5 vs. 123.5 | 79.9 | 37.2 |

| 125.5 vs. 126.5 | 78.2 | 41.9 |

| 130.5 vs. 132.5 | 75.3 | 46.5 |

| 133.5 vs. 135.5 | 69.5 | 55.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maheu, C.; Singh, M.; Tock, W.L.; Robert, J.; Vodermaier, A.; Parkinson, M.; Dolgoy, N. The Cancer and Work Scale (CAWSE): Assessing Return to Work Likelihood and Employment Sustainability After Cancer. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32030166

Maheu C, Singh M, Tock WL, Robert J, Vodermaier A, Parkinson M, Dolgoy N. The Cancer and Work Scale (CAWSE): Assessing Return to Work Likelihood and Employment Sustainability After Cancer. Current Oncology. 2025; 32(3):166. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32030166

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaheu, Christine, Mina Singh, Wing Lam Tock, Jennifer Robert, Andrea Vodermaier, Maureen Parkinson, and Naomi Dolgoy. 2025. "The Cancer and Work Scale (CAWSE): Assessing Return to Work Likelihood and Employment Sustainability After Cancer" Current Oncology 32, no. 3: 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32030166

APA StyleMaheu, C., Singh, M., Tock, W. L., Robert, J., Vodermaier, A., Parkinson, M., & Dolgoy, N. (2025). The Cancer and Work Scale (CAWSE): Assessing Return to Work Likelihood and Employment Sustainability After Cancer. Current Oncology, 32(3), 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32030166