Perceived Quality-of-Life Importance Among Saudi Gynecologic Cancer Survivors: Latent Class Analysis

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Survey Instrument and Domain Importance Ratings

- Sexual Function and Satisfaction (8 items);

- Psychological and Emotional Well-Being (3 items);

- Social and Relationship Quality (3 items).

3. Results

3.1. Interpretation of Response Probabilities by Latent Class Analysis

3.2. Sociodemographic and Clinical Profiles by Latent Class Group

3.3. Predictors of High-Importance Class Group (Non-Parametric Analysis)

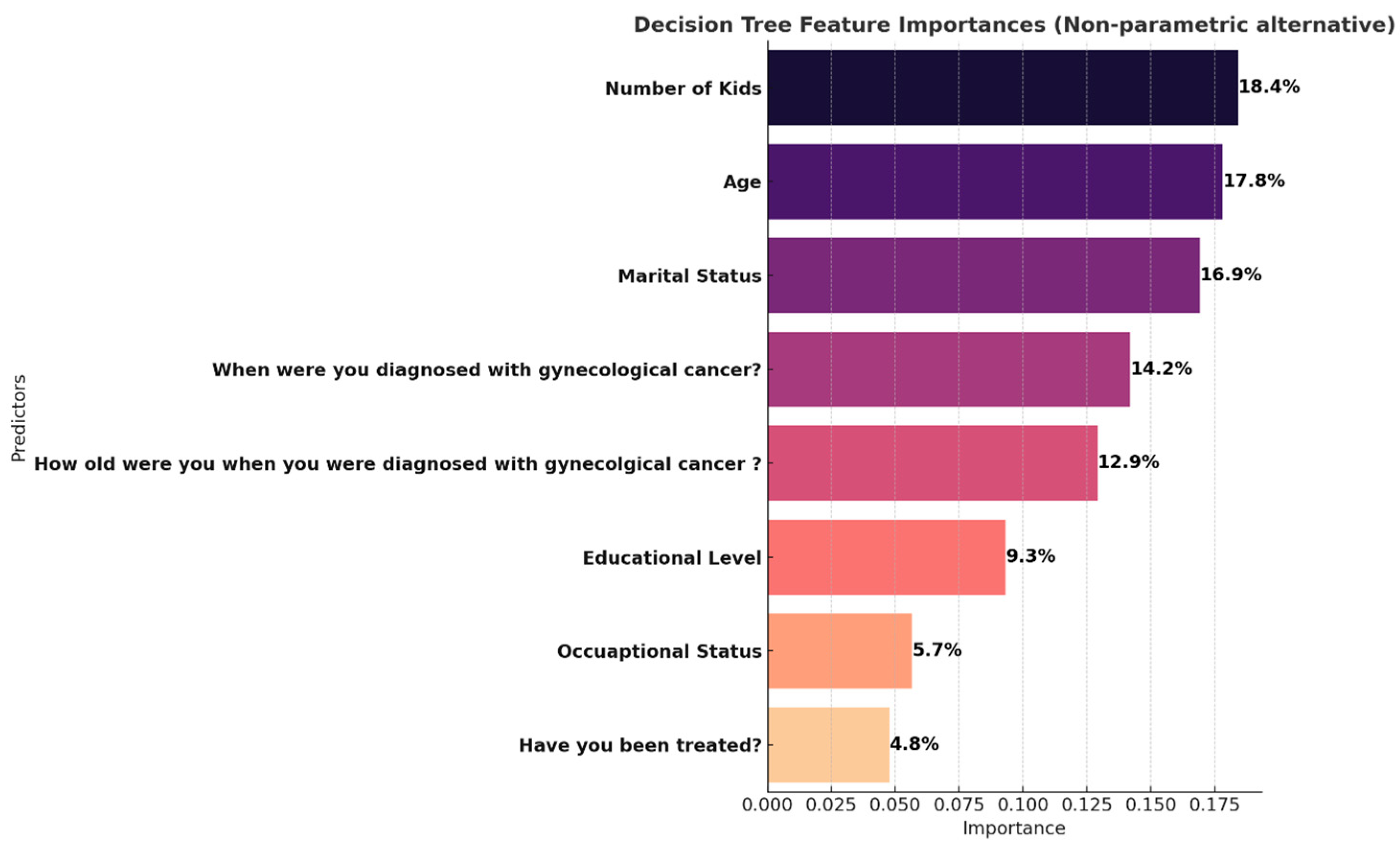

3.4. Summary

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DOAJ | Directory of open access journals |

| TLA | Three-letter acronym |

| LD | Linear dichroism |

References

- Basudan, A.M. Breast cancer incidence patterns in the Saudi female population: A 17-year retrospective analysis. Medicina 2022, 58, 1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Cervical Cancer Country Profile: Saudi Arabia. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/cervical-cancer-sau-country-profile-2021 (accessed on 9 April 2021).

- Alattar, N.; Felton, A.; Stickley, T. Mental health and stigma in Saudi Arabia: A scoping review. Ment. Health Rev. J. 2021, 26, 180–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alissa, N.A. Social barriers as a challenge in seeking mental health among Saudi Arabians. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2021, 10, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vegunta, S.; Kuhle, C.L.; Vencill, J.A.; Lucas, P.H.; Mussallem, D.M. Sexual health after a breast cancer diagnosis: Addressing a forgotten aspect of survivorship. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, M.; Mardani, A.; Ghafourifard, M.; Vaismoradi, M. Qualitative exploration of sexual life among breast cancer survivors at reproductive age. BMC Women′s Health 2021, 21, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alomair, N.; Alageel, S.; Davies, N.; Bailey, J.V. Barriers to sexual and reproductive wellbeing among Saudi women: A qualitative study. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy 2021, 19, 860–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alomair, N. Sexual and Reproductive Health of Women in Saudi Arabia: Needs, Perceptions, and Experiences. Ph.D. Thesis, UCL (University College London), London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Dangerfield, D.T., II. Using Person-Centered Statistical Approaches for Study and Intervention Design. In Prevention Science & Targeted Methods for HIV/STI Research with Black Sexual Minority Men; Spinger: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 65–77. [Google Scholar]

- Wiehn, E.; Ricci, C.; Alvarez-Perea, A.; Perkin, M.R.; Jones, C.J.; Akdis, C.; Bousquet, J.; Eigenmann, P.; Grattan, C.; Apfelbacher, C.J.; et al. Adherence to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist in articles published in EAACI Journals: A bibliographic study. Allergy 2021, 76, 3581–3588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahmoud, A.; Russell, R.; Kelley, E.; Fraiman, E.; Goldblatt, C.; Loria, M.; Mishra, K.; Gupta, S.; Pope, R. Sexual satisfaction and function (SatisFunction) survey post-vaginoplasty for transgender and gender diverse individuals: Preliminary development and content validity for future clinical use. Sex. Med. 2025, 13, qfaf011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberguggenberger, A.; Martini, C.; Huber, N.; Fallowfield, L.; Hubalek, M.; Daniaux, M.; Sperner-Unterweger, B.; Holzner, B.; Sztankay, M.; Gamper, E.; et al. Self-reported sexual health: Breast cancer survivors compared to women from the general population–an observational study. BMC Cancer 2017, 17, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, B.; Barclay, S.; Kuhn, I.; Eagar, K.; Bausewein, C.; Murtagh, F.; Etkind, S.; Bowers, B.; Dixon, S.; Lovick, R.; et al. Implementing patient-centred outcome measures in palliative care clinical practice for adults (IMPCOM): Protocol for an update systematic review of facilitators and barriers. F1000Research 2023, 12, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younan, L.S.; Clinton, M.E.; Fares, S.A.; Samaha, H. The translation and cultural adaptation validity of the Actual Scope of Practice Questionnaire. East Mediterr Health J. 2019, 25, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, A.; Elmer, M.; Ludlam, S.; Shay, K.; Bentley, S.; Trennery, C.; Grimes, R.; Gater, A. Evaluation of the content validity and cross-cultural validity of the study participant feedback questionnaire (SPFQ). Ther. Innov. Regul. Sci. 2020, 54, 1522–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forero, C.G. Cronbach’s alpha. In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 1505–1507. [Google Scholar]

- Weller, B.E.; Bowen, N.K.; Faubert, S.J. Latent class analysis: A guide to best practice. J. Black Psychol. 2020, 46, 287–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yenipınar, A.; Koç, Ş.; Çanga, D.; Kaya, F. Determining sample size in logistic regression with G-Power. Black Sea J. Eng. Sci. 2019, 2, 16–22. [Google Scholar]

- Chong, J.L.; Lim, K.K.; Matchar, D.B. Population segmentation based on healthcare needs: A systematic review. Syst. Rev. 2019, 8, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, H.; Wang, H.; Scotney, B.; Liu, J. A novel Gaussian mixture model for classification. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man and Cybernetics (SMC), Bari, Italy, 6–9 October 2019; pp. 3298–3303. [Google Scholar]

- Lezhnina, O.; Kismihók, G. Latent class cluster analysis: Selecting the number of clusters. MethodsX 2022, 9, 101747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Xu, S. NCART: Neural Classification and Regression Tree for tabular data. Pattern Recognit. 2024, 154, 110578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, L.; Miao, Y.M.; Dong, X.J.; Zhang, Q.R.; Ren, Q.; Zhang, N. Investigation on sexual function in young breast cancer patients during endocrine therapy: A latent class analysis. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1218369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Xiao, P.; Deng, W.; Wong, C.L.; Ngan, C.K.; Tso, W.W.Y.; Leung, A.W.K.; Loong, H.H.F.; Li, C.K.; Chan, A.; et al. Psychosocial challenges among Asian adolescents and young adults with cancer: A scoping review. BMC Cancer 2025, 25, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Xue, B.; Li, L.; Qiao, J.; Redding, S.R.; Ouyang, Y.Q. Psychological interventions for sexual function and satisfaction of women with breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Nurs. 2023, 32, 2282–2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shams, M.; Coman, C.; Fatone, F.; Marenesi, V.; Bernorio, R.; Feltrin, A.; Groff, E. The impact of gynecologic cancer on female sexuality in Europe and MENA (Middle East and North Africa): A literature review. Sex. Med. Rev. 2024, 12, 587–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwozichi, C.U.; Ojewale, M.O.; Salako, O.; Brotobor, D.; Olaogun, E. The Lived Experience of Suffering by Nigerian Female Breast Cancer Survivors: A Phenomenological Perspective. J. Patient Exp. 2025, 12, 23743735251314858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kechagioglou, P.; Fuller-Shavel, N. Early Survivorship: Rehabilitation and Reintegration. In Integrative Oncology in Breast Cancer Care; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 123–132. [Google Scholar]

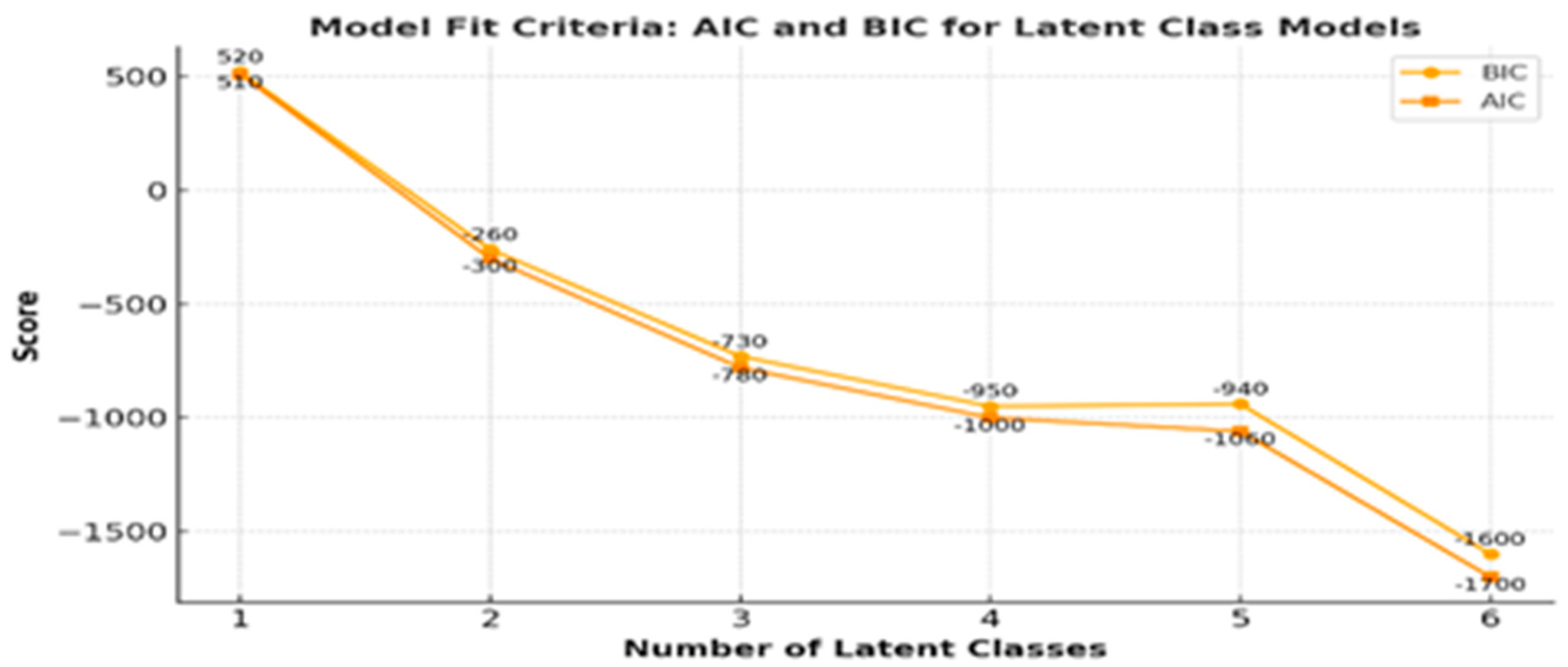

| Classes | Log Likelihood | AIC a | BIC b | Entropy | Class Probabilities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 class | −237.54 | 510 | 520 | --- | --- |

| 2 class | 183.63 | −300 | −260 | 0.81 | 0.512, 0.488 |

| 3 class | 439.63 | −780 | −730 | 0.84 | 0.178, 0.488, 0.333 |

| 4 class | 464.59 | −1000 | −950 | 0.91 | 0.155, 0.488, 0.333, 0.023 |

| 5 class | 606.77 | −1060 | −940 | 0.96 | 0.155, 0.488, 0.008, 0.016, 0.333 |

| 6 class | 617.45 | −1700 | −1600 | 0.98 | 0.155, 0.442, 0.140, 0.016, 0.194, 0.054 |

| Variable | Category | Class 0 a (n, %) | Class 1 b (n, %) | Class 2 c (n, %) | p-Value d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | ----------- | 63 (48.83%) | 23 (17.8%) | 43 (33.3%) | |

| Age | From 21 to 30 Years | 23 (36.5%) | 12 (52.2%) | 8 (18.6%) | 0.001 |

| From 31 to 45 Years | 34 (54.0%) | 6 (26.1%) | 19 (44.2%) | ||

| More than 45 Years | 6 (9.5%) | 5 (21.7%) | 16 (37.2%) | ||

| Marital Status | Married | 53 (84.1%) | 21 (91.3%) | 33 (76.7%) | 0.31 |

| Nonmarried | 10 (15.9%) | 2 (8.7%) | 10 (23.3%) | ||

| Educational Level | Bachelor | 35 (55.6%) | 14 (60.9%) | 13 (30.2%) | 0.04 |

| Graduate studies | 7 (11.1%) | 2 (8.7%) | 4 (9.3%) | ||

| Secondary or Less | 21 (33.3%) | 7 (30.4%) | 26 (60.5%) | ||

| Nationality | Non-Saudi | 2 (3.2%) | 3 (13.0%) | 8 (18.6%) | 0.03 |

| Saudi | 61 (96.8%) | 20 (87.0%) | 35 (81.4%) | ||

| Occupational Status | Employed | 33 (52.4%) | 8 (34.8%) | 15 (34.9%) | 0.13 |

| Unemployed | 30 (47.6%) | 15 (65.2%) | 28 (65.1%) | ||

| Number of kids | From 1 to 3 | 38 (60.3%) | 7 (30.4%) | 14 (32.6%) | 0.0001 |

| From 4 to 10 | 10 (15.9%) | 13 (56.5%) | 27 (62.8%) | ||

| None | 15 (23.8%) | 3 (13.0%) | 2 (4.7%) | ||

| Age when you first diagnosis | From 21 to 30 Years | 33 (52.4%) | 13 (56.5%) | 14 (32.6%) | 0.03 |

| From 31 to 45 Years | 24 (38.1%) | 8 (34.8%) | 16 (37.2%) | ||

| More than 45 Years | 6 (9.5%) | 2 (8.7%) | 13 (30.2%) | ||

| When were you diagnosed with gynecological cancer? | From 1 to 3 Years | 40 (63.5%) | 13 (56.5%) | 26 (60.5%) | 0.05 |

| Less than 1 Year | 16 (25.4%) | 3 (13.0%) | 4 (9.3%) | ||

| More than 3 Years | 7 (11.1%) | 7 (30.4%) | 12 (27.9%) | ||

| Type of diagnosed cancer | Breast cancer | 38 (60.3%) | 7 (30.4%) | 18 (41.9%) | 0.03 |

| Cervical cancer | 25 (39.7%) | 16 (69.6%) | 25 (58.1%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Almutairi, W.M.; Alsharif, F.; Al-Zahrani, A.; Bin Afeef, N.; Alkeai, A.; Alfakeeh, H.; Alzahrani, A.; Katooa, N.E.; Kassem, F.K.; Faheem, W.A. Perceived Quality-of-Life Importance Among Saudi Gynecologic Cancer Survivors: Latent Class Analysis. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 557. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32100557

Almutairi WM, Alsharif F, Al-Zahrani A, Bin Afeef N, Alkeai A, Alfakeeh H, Alzahrani A, Katooa NE, Kassem FK, Faheem WA. Perceived Quality-of-Life Importance Among Saudi Gynecologic Cancer Survivors: Latent Class Analysis. Current Oncology. 2025; 32(10):557. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32100557

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlmutairi, Wedad M., Fatmah Alsharif, Ahlam Al-Zahrani, Noura Bin Afeef, Alkhnsa Alkeai, Haneen Alfakeeh, Arwa Alzahrani, Nouran Essam Katooa, Fathia Khamis Kassem, and Wafa A. Faheem. 2025. "Perceived Quality-of-Life Importance Among Saudi Gynecologic Cancer Survivors: Latent Class Analysis" Current Oncology 32, no. 10: 557. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32100557

APA StyleAlmutairi, W. M., Alsharif, F., Al-Zahrani, A., Bin Afeef, N., Alkeai, A., Alfakeeh, H., Alzahrani, A., Katooa, N. E., Kassem, F. K., & Faheem, W. A. (2025). Perceived Quality-of-Life Importance Among Saudi Gynecologic Cancer Survivors: Latent Class Analysis. Current Oncology, 32(10), 557. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32100557