The Role of Telemedicine for Psychological Support for Oncological Patients Who Have Received Radiotherapy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- A descriptive collection of personality features, psychosocial elements and cognitive and emotional processing capacity regarding the event, paying attention to the patient’s history.

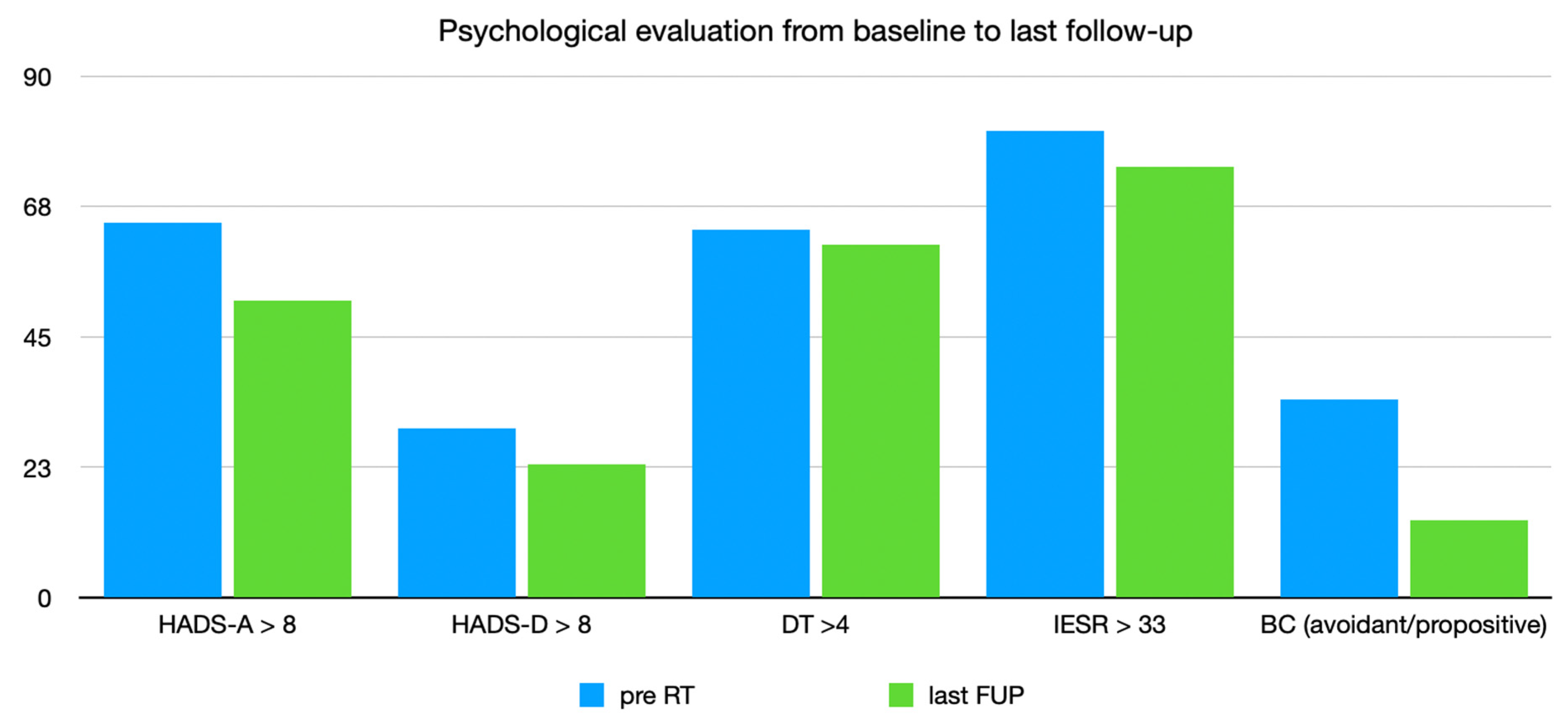

- An evaluation of anxiety and depression with Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS) [31,32], which is a four-point scale (from 0 to 3) consisting of 14 questions to which the patients had to respond, referring to their symptoms during the previous week. The HADS scale is divided into 2 subscales which investigate anxiety (HADS-A) and depression (HADS-D), respectively. Seven of the 14 elements of the HADS scale correspond to the HADS-A subscale and the remaining 7 to the HADS-D subscale, ranging from 0 (no discomfort) to 21 (extreme discomfort). Scores of 8 or more in both subscales indicate the presence of a disorder.

- An evaluation of distress using the Distress Thermometer (DT) [33]. It is a single-item instrument, consisting of a visual analog scale and represented by a thermometer ranging from 0 (no discomfort) to 10 (extreme discomfort). A score of 4 or more indicates the presence of a disorder.

- An assessment of the varying coping strategies used by patients in response to stress by the Brief COPE (BC) [34,35]. It is an instrument composed of 14 scales for a total of 28 items (positive restructuring, distracting attention, expression, use of instrumental support, operational coping, denial, religion, humor, behavioral disengagement, use of emotional support, substance use, acceptance, planning, self-accusation).

- An evaluation of post-traumatic stress symptoms using the Impact of Event Scale-revised (IES-R) [36]. The IES-R is a 22-item self-report measure (for DSM-IV) that assesses subjective distress caused by traumatic events. It is a revised version of the older version; the IES-R contains 7 additional items related to the hyperarousal symptoms of PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder), which were not included in the original IES. Respondents are asked to identify a specific stressful life event and then indicate how much they were distressed or bothered during the previous seven days by each “difficulty” listed. Items are rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (“not at all”) to 4 (“extremely”). The IES-R yields a total score (ranging from 0 to 88); significant symptoms were defined by a score of more than 33.

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Overall Population Who Received Psychological Assessment during RT

Population Followed after RT: Tele-Visit Versus in-Person Evaluation

4. Discussion

- First of all, in the TC group, a predominance of poor-prognosis diseases was present (brain tumor, metastatic tumor and head and neck tumor), with a high incidence of recurrence post-treatment and a subsequent higher anxiety score.

- In the OS group, most of the patients had breast cancer (young patients with good prognosis); the high level of anxiety (Figure 2) was also reduced during follow-up because no recurrence was reported.

- For phycologists, the evaluation of expression throughout the body is more difficult to evaluate during tele-consults; thus, the psychological strategy could be longer and less precise. The present data are in line with a recent Cochrane publication. The predominance of telephone-delivered interventions for psychological symptoms is unsurprising. Telephone counseling has been shown to be effective in reducing psychological symptoms, including depression and anxiety, in patient populations other than those affected by cancer. Further, this review has demonstrated that telephone-delivered interventions are being developed for managing a range of physical as well as psychological cancer-related symptoms [38].

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Szcześniak, D.; Gładka, A.; Misiak, B.; Cyran, A.; Rymaszewska, J. The SARS-CoV-2 and mental health: From biological mechanisms to social consequences. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2021, 104, 110046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salari, N.; Hosseinian-Far, A.; Jalali, R.; Vaisi-Raygani, A.; Rasoulpoor, S.; Mohammadi, M.; Rasoulpoor, S.; Khaledi-Paveh, B. Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Glob. Health 2020, 16, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miaskowski, C.; Paul, S.M.; Snowberg, K.; Abbott, M.; Borno, H.; Chang, S.; Chen, L.M.; Cohen, B.; Hammer, M.J.; Kenfield, S.A.; et al. Stress and Symptom Burden in Oncology Patients during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2020, 60, e25–e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fung, M.; Babik, J.M. COVID-19 in Immunocompromised Hosts: What We Know So Far. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 72, 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuderer, N.M.; Choueiri, T.K.; Shah, D.P.; Shyr, Y.; Rubinstein, S.M.; Rivera, D.R.; Shete, S.; Hsu, C.-Y.; Desai, A.; de Lima Lopes, G., Jr.; et al. Clinical impact of COVID-19 on patients with cancer (CCC19): A cohort study. Lancet 2020, 395, 1907–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.Y.W.; Cazier, J.-B.; Angelis, V.; Arnold, R.; Bisht, V.; Campton, N.A.; Chackathayil, J.; Cheng, V.W.T.; Curley, H.M.; Fittall, M.W.T.; et al. COVID-19 mortality in patients with cancer on chemotherapy or other anticancer treatments: A prospective cohort study. Lancet 2020, 395, 1919–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Shamsi, H.O.; Alhazzani, W.; Alhuraiji, A.; Coomes, E.A.; Chemaly, R.F.; Almuhanna, M.; Wolff, R.A.; Ibrahim, N.K.; Chua, M.L.; Hotte, S.J.; et al. A Practical Approach to the Management of Cancer Patients during the Novel Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic: An International Collaborative Group. Oncologist 2020, 25, e936–e945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Haar, J.; Hoes, L.R.; Coles, C.E.; Seamon, K.; Fröhling, S.; Jäger, D.; Valenza, F.; de Braud, F.; De Petris, L.; Bergh, J.; et al. Caring for patients with cancer in the COVID-19 era. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 665–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregucci, F.; Caliandro, M.; Surgo, A.; Carbonara, R.; Bonaparte, I.; Fiorentino, A. Cancer patients in COVID-19 era: Swimming against the tide. Radiother. Oncol. 2020, 149, 109–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalmbach, D.A.; Cuamatzi-Castelan, A.S.; Tonnu, C.V.; Tran, K.M.; Anderson, J.R.; Roth, T.; Drake, C.L. Hyperarousal and sleep reactivity in insomnia: Current insights. Nat. Sci. Sleep 2018, 10, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, P.B. Screening for Psychological Distress in Cancer Patients: Challenges and Opportunities. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 25, 4526–4527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brintzenhofe-Szoc, K.M.; Levin, T.T.; Li, Y.; Kissane, D.W.; Zabora, J.R. Mixed Anxiety/Depression Symptoms in a Large Cancer Cohort: Prevalence by Cancer Type. Psychosomatics 2009, 50, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stiegelis, H.E.; Ranchor, A.V.; Sanderman, R. Psychological functioning in cancer patients treated with radiotherapy. Patient Educ. Couns. 2004, 52, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linden, W.; Vodermaier, A.; MacKenzie, R.; Greig, D. Anxiety and depression after cancer diagnosis: Prevalence rates by cancer type, gender, and age. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 141, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juanjuan, L.; Santa-Maria, C.A.; Hongfang, F.; Lingcheng, W.; Pengcheng, Z.; Yuanbing, X.; Yuyan, T.; Zhongchun, L.; Bo, D.; Meng, L.; et al. Patient-reported Outcomes of Patients with Breast Cancer v the COVID-19 Outbreak in the Epicenter of China: A Cross-sectional Survey Study. Clin. Breast Cancer 2020, 20, e651–e662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Duan, Z.; Ma, Z.; Mao, Y.; Li, X.; Wilson, A.; Qin, H.; Ou, J.; Peng, K.; Zhou, F.; et al. Epidemiology of mental health problems among patients with cancer during COVID-19 pan-demic. Transl. Psychiatry 2020, 10, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romito, F.; Dellino, M.; Loseto, G.; Opinto, G.; Silvestris, E.; Cormio, C.; Guarini, A.; Minoia, C. Psychological Distress in Outpatients with Lymphoma during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorentino, A.; Mazzola, R.; Lancellotta, V.; Saldi, S.; Chierchini, S.; Alitto, A.R.; Borghetti, P.; Gregucci, F.; Fiore, M.; Desideri, I.; et al. Evaluation of Italian radiotherapy research from 1985 to 2005: Preliminary analysis. La Radiol. Med. 2019, 124, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buse, C.R.; Kelly, E.A.; Muss, H.B.; Nyrop, K.A. Perspectives of older women with early breast cancer on telemedicine during post-primary treatment. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 9859–9868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, N.Q.; Lau, J.; Fong, S.Y.; Wong, C.Y.H.; Tan, K.K. Telemedicine acceptance among older adult patients with cancer: Scoping review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e28724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B.A.; Hui, J.Y.C. ASO author reflections: The patient perspective of telemedicine in breast cancer care. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2022, 29, 3859–3860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irfan, A.; Lever, J.M.; Fouad, M.N.; Sleckman, B.P.; Smith, H.; Chu, D.I.; Rose, J.B.; Wang, T.N.; Reddy, S. Does health literacy impact technological comfort in cancer patients? Am. J. Surg. 2022, 223, 722–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zomerdijk, N.; Jongenelis, M.; Yuen, E.; Turner, J.; Huntley, K.; Smith, A.; McIntosh, M.; Short, C.E. Experiences and needs of people with haematological cancers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study. Psychooncology 2022, 31, 416–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heyer, A.; Granberg, R.E.; Rising, K.L.; Binder, A.F.; Gentsch, A.T.; Handley, N.R. Medical oncology professionals’ perceptions of telehealth video visits. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2033967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizot, A.; Karimi, M.; Rassy, E.; Heudel, P.E.; Levy, C.; Vanlemmens, L.; Uzan, C.; Deluche, E.; Genet, D.; Saghatchian, M.; et al. Multicenter evaluation of breast cancer patients’ satisfaction and experience with on-cology telemedicine visits during the COVID-19 pandemic. Br. J. Cancer 2021, 125, 1486–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moentmann, M.R.; Johnson, J.; Chung, M.T.; Yoo, O.E.; Lin, H.; Yoo, G.H. Telemedicine trends at a comprehensive cancer center during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Surg. Oncol. 2022, 125, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, R.; Crichton, M.; Crawford-Williams, F.; Agbejule, O.; Yu, K.; Hart, N.; Alves, F.D.A.; Ashbury, F.; Eng, L.; Fitch, M.; et al. The efficacy, challenges, and facilitators of telemedicine in post-treatment cancer survivorship care: An overview of systematic reviews. Ann. Oncol. 2021, 32, 1552–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B.A.; Lindgren, B.R.; Blaes, A.H.; Parsons, H.M.; LaRocca, C.J.; Farah, R.; Hui, J.Y.C. The new normal? Patient satisfaction and usability of telemedicine in breast cancer care. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2021, 28, 5668–5676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, K.R.; Kain, D.; Merchant, S.; Booth, C.; Koven, R.; Brundage, M.; Galica, J. Older survivors of cancer in the COVID-19 pandemic: Reflections and recom-mendations for future care. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2021, 12, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Street, R.L.; Treiman, K.; Kranzler, E.C.; Moultrie, R.; Arena, L.; Mack, N.; Garcia, R. Oncology patients’ communication experiences during COVID-19: Comparing telehealth consultations to in-person visits. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 4769–4780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantini, M.; Musso, M.; Viterbori, P.; Bonci, F.; Del Mastro, L.; Garrone, O.; Venturini, M.; Morasso, G. Detecting psychologicaldistress in cancer patients: Validaty of the italian verson of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Support. Care Cancer 1999, 7, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabbri, C.; Nesti, S.; Franchi, G.; Grechi, E.; Maruelli, A.; Muraca, M.G.; Miccinesi, G. Screening del distress in un centro di riabilitazione oncologica: Variabili legate all’accettazione del colloquio psicologico. Giornale Italiano di Psico-Oncologia 2014, 16, 55–60. [Google Scholar]

- Feeney, J.A.; Noller, H.; Hanrahan, M. Assessing adult attachment. In Attacchment in Adult. Clinical and Developmental Perspective; Sperling, M.B., Berman, W.H., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994; pp. 128–152. [Google Scholar]

- Carver, C.S. You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: Consider the Brief COPE. Int. J. Behav. Med. 1997, 4, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheli, S.; Caligiani, L.; Martella, F.; De Bartolo, P.; Mancini, F.; Fioretto, L. Mindfulness and metacognition in facing with fear of recurrence: A proof-of-concept study with breast-cancer women. Psycho-Oncology 2019, 28, 600–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creamer, M.; Bell, R.; Failla, S. Psychometric properties of the Impact of Event Scale—Revised. Behav. Res. Ther. 2003, 41, 1489–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillan, C.; Abrams, D.; Harnett, N.; Wiljer, D.; Catton, P. Fears and Misperceptions of Radiation Therapy: Sources and Impact on Decision-Making and Anxiety. J. Cancer Educ. 2014, 29, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ream, E.; Hughes, A.E.; Cox, A.; Skarparis, K.; Richardson, A.; Pedersen, V.H.; Wiseman, T.; Forbes, A.; Bryant, A. Telephone interventions for symptom management in adults with cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 6, CD007568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caliandro, M.; Fabiana, G.; Surgo, A.; Carbonara, R.; Ciliberti, M.P.; Bonaparte, I.; Caputo, S.; Fiorentino, A. Impact on mental health of the COVID-19 pandemic in a radiation oncology department. La Radiol. Med. 2022, 127, 220–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total Number of Patients (pts) | 82 |

|---|---|

| Group OS | 30 pts (36.6%) |

| Median age (range) | 51 years (35–67) |

| Sex (male:female) | 5:25 |

| Type of cancer | |

| Breast | 18 |

| Prostate | 2 |

| Gynecological | 3 |

| Others | 7 |

| Median RT session (range) | 21 (5–30) |

| Median psycho-therapeutic meetings (range) | 3.5 (2–5) |

| Median psycho-therapeutic meetings in FUP (range) | 8 (4–28) |

| Group TC | 52 pts (63.4%) |

| Median age (range) | 48.5 years (18–75) |

| Sex (male:female) | 16:36 |

| Type of cancer | |

| Breast | 21 |

| Brain | 10 |

| Prostate | 4 |

| Gynecological | 5 |

| Others | 12 |

| Median RT session (range) | 23 (10–33) |

| Median psycho-therapeutic meetings (range) | 4 (2–6) |

| Median psycho-therapeutic meetings in FUP (range) | 8 (4–24) |

| RT: radiotherapy; OS: on-site; TC: tele-consult | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Caliandro, M.; Carbonara, R.; Surgo, A.; Ciliberti, M.P.; Di Guglielmo, F.C.; Bonaparte, I.; Paulicelli, E.; Gregucci, F.; Turchiano, A.; Fiorentino, A. The Role of Telemedicine for Psychological Support for Oncological Patients Who Have Received Radiotherapy. Curr. Oncol. 2023, 30, 5158-5167. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30050390

Caliandro M, Carbonara R, Surgo A, Ciliberti MP, Di Guglielmo FC, Bonaparte I, Paulicelli E, Gregucci F, Turchiano A, Fiorentino A. The Role of Telemedicine for Psychological Support for Oncological Patients Who Have Received Radiotherapy. Current Oncology. 2023; 30(5):5158-5167. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30050390

Chicago/Turabian StyleCaliandro, Morena, Roberta Carbonara, Alessia Surgo, Maria Paola Ciliberti, Fiorella Cristina Di Guglielmo, Ilaria Bonaparte, Eleonora Paulicelli, Fabiana Gregucci, Angela Turchiano, and Alba Fiorentino. 2023. "The Role of Telemedicine for Psychological Support for Oncological Patients Who Have Received Radiotherapy" Current Oncology 30, no. 5: 5158-5167. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30050390

APA StyleCaliandro, M., Carbonara, R., Surgo, A., Ciliberti, M. P., Di Guglielmo, F. C., Bonaparte, I., Paulicelli, E., Gregucci, F., Turchiano, A., & Fiorentino, A. (2023). The Role of Telemedicine for Psychological Support for Oncological Patients Who Have Received Radiotherapy. Current Oncology, 30(5), 5158-5167. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30050390