Reduced Psychosocial Well-Being among the Children of Women with Early-Onset Breast Cancer

Abstract

:1. Introduction

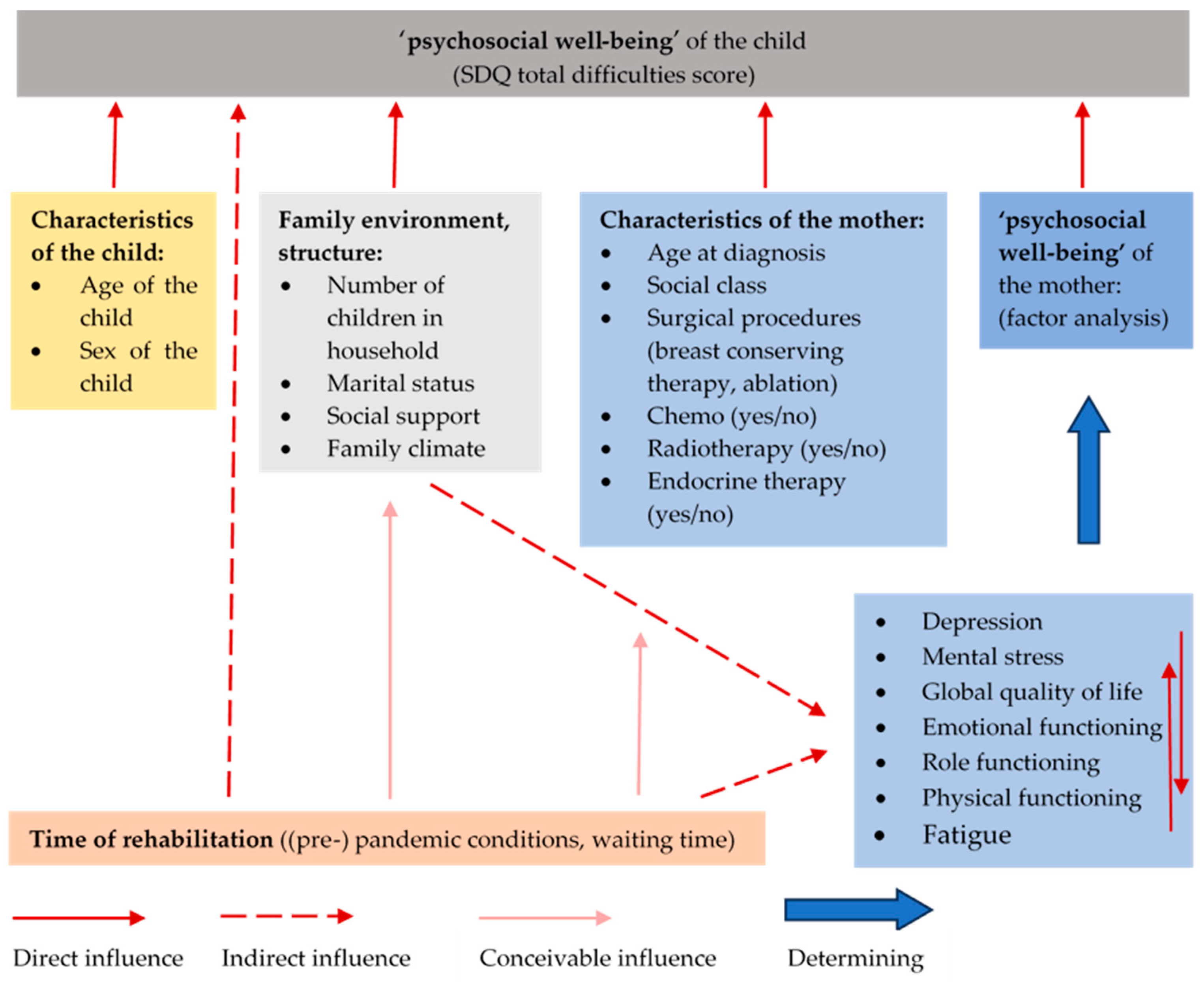

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Data Sources

2.3. Statistics

2.4. Ethics

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Mothers

3.2. Characteristics of the Children

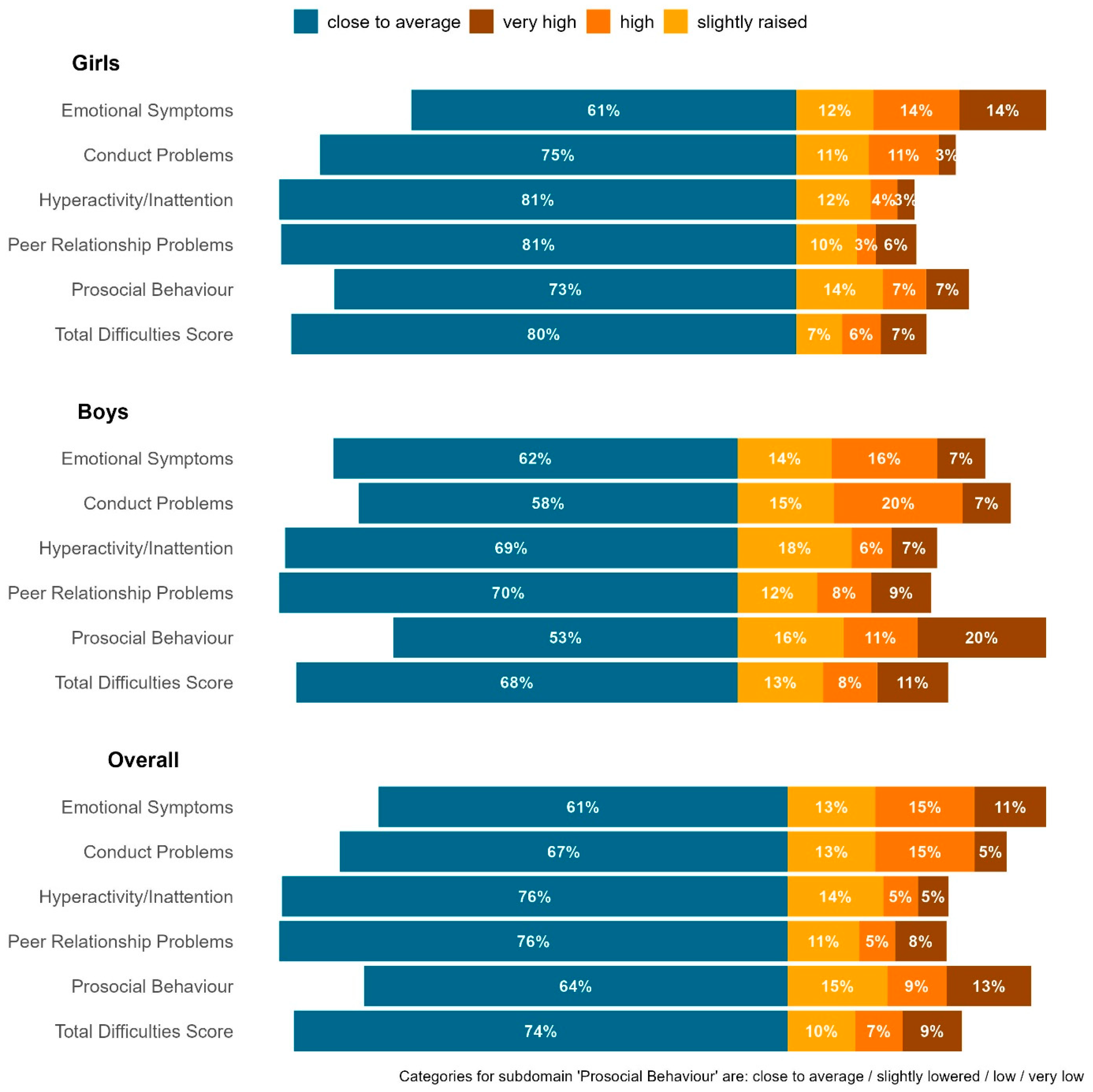

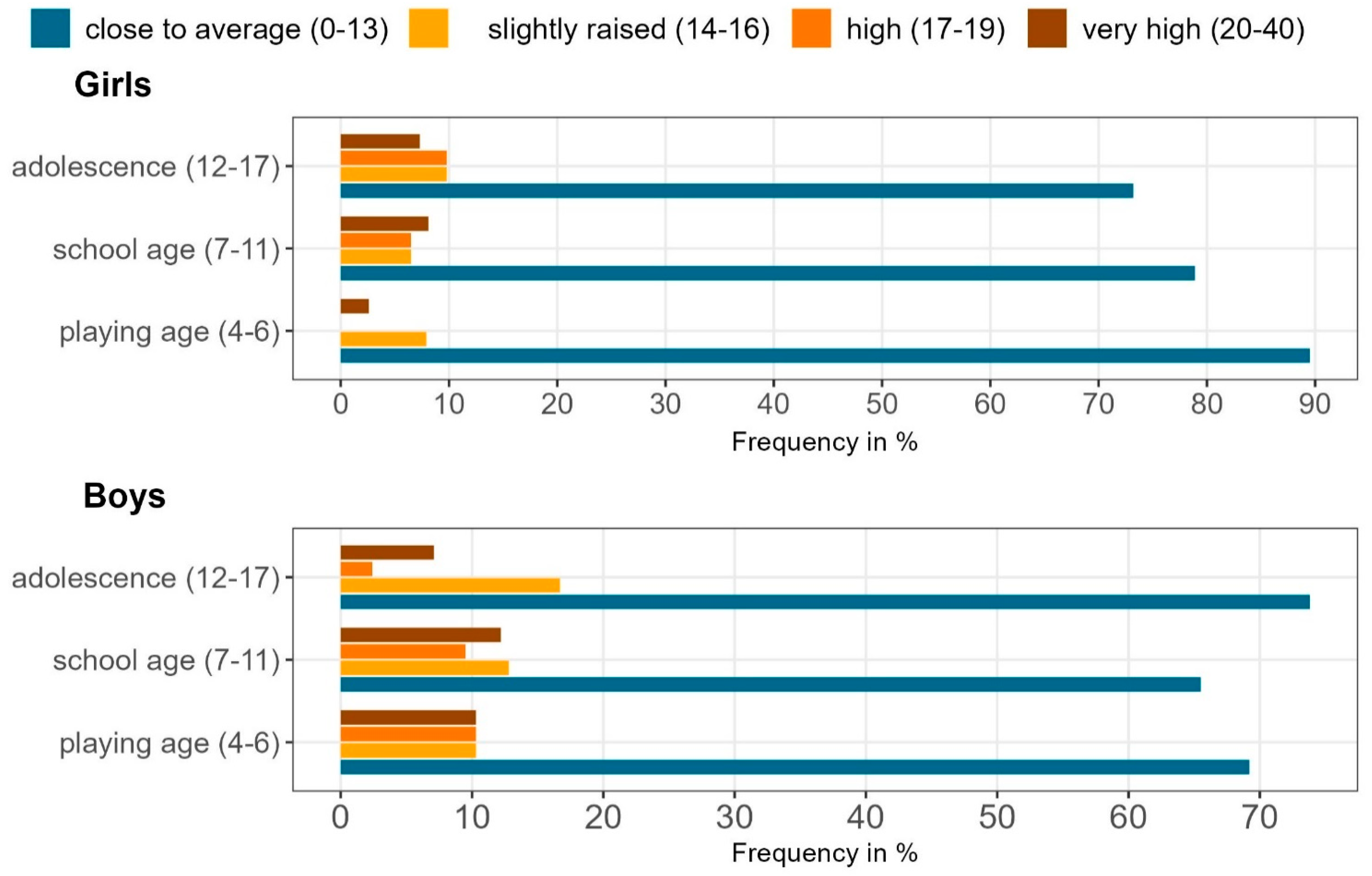

3.3. Psychosocial Well-Being in Children

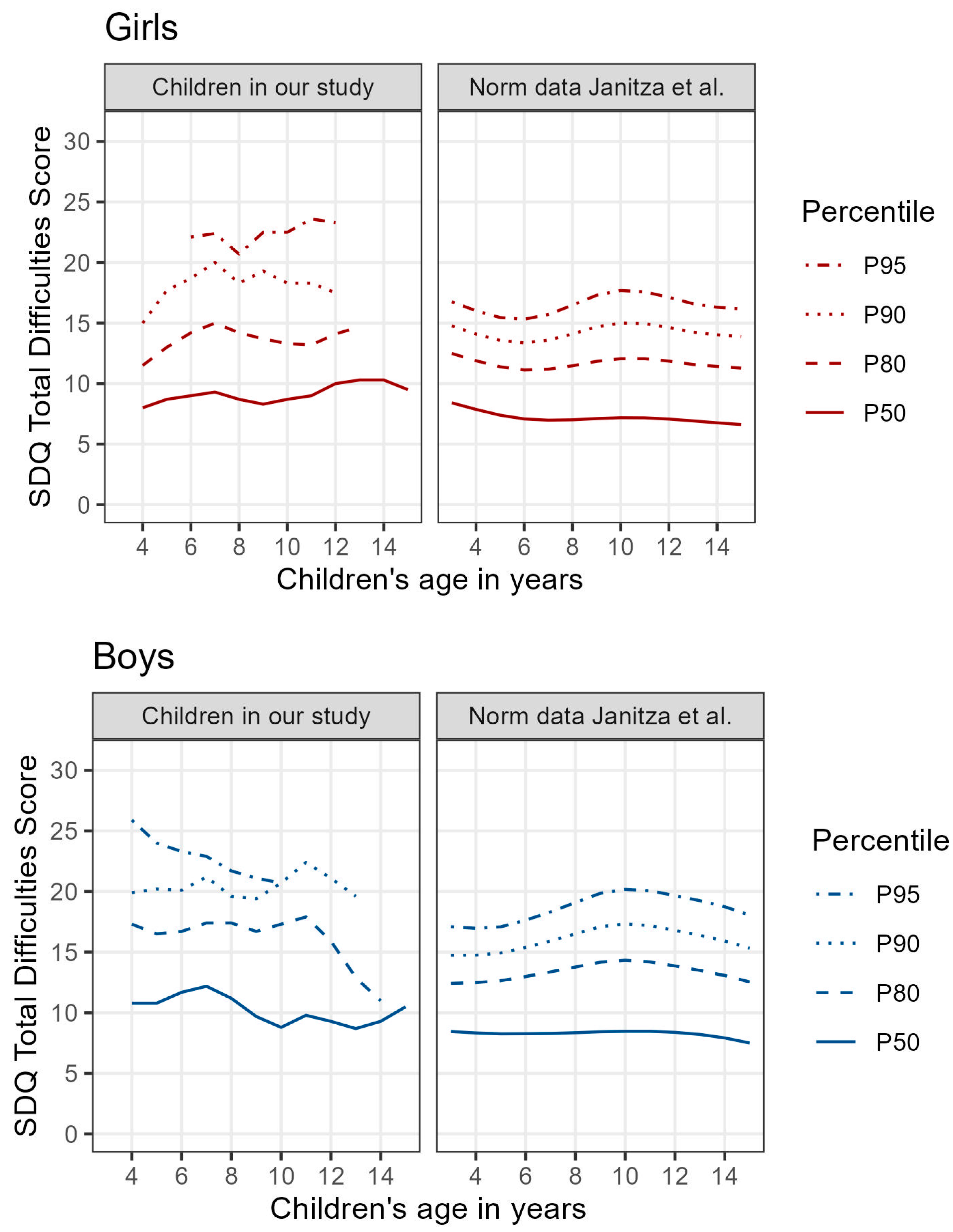

3.4. Comparison of SDQ Scores with Normative and Other Clinical Cohorts

3.5. Factors Influencing Children’s Psychosocial Well-Being—Results of Multivariable Regression Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Psychosocial Well-Being of Mothers with Early-Onset Breast Cancer

4.2. Children’s Psychosocial Well-Being and Comparisons with the Woerner et al. Cohorts

4.3. Factors Influencing Children’s Psychosocial Well-Being

4.4. Strengths and Weaknesses

4.5. Implications for Clinical Practice

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Waldfogel, J.; Craigie, T.-A.; Brooks-Gunn, J. Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing. Future Child. Cent. Future Child. David Lucile Packard Found. 2010, 20, 87–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huizinga, G.A.; Visser, A.; Zelders-Steyn, Y.E.; Teule, J.A.; Reijneveld, S.A.; Roodbol, P.F. Psychological Impact of Having a Parent with Cancer. Eur. J. Cancer Oxf. Engl. 2011, 47 (Suppl. S3), S239–S246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singer, S. Psychosocial Impact of Cancer. In Recent Results in Cancer Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; Volume 210, pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zentrum für Krebsregisterdaten (ZfKD) im Robert Koch-Institut Datensatz Des ZfKD Auf Basis Der Epidemiologischen Landeskrebsregisterdaten Epi2021_3, Verfügbare Diagnosejahre Bis 2019. Available online: https://www.krebsdaten.de/Krebs/DE/Datenbankabfrage/datenbankabfrage_stufe1_node.html (accessed on 28 September 2023).

- Rosenberg, S.M.; Vaz-Luis, I.; Gong, J.; Rajagopal, P.S.; Ruddy, K.J.; Tamimi, R.M.; Schapira, L.; Come, S.; Borges, V.; de Moor, J.S.; et al. Employment Trends in Young Women Following a Breast Cancer Diagnosis. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2019, 177, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard-Anderson, J.; Ganz, P.A.; Bower, J.E.; Stanton, A.L. Quality of Life, Fertility Concerns, and Behavioral Health Outcomes in Younger Breast Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2012, 104, 386–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purc-Stephenson, R.; Lyseng, A. How Are the Kids Holding up? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis on the Psychosocial Impact of Maternal Breast Cancer on Children. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2016, 49, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- John, K.; Becker, K.; Mattejat, F. Mothers with breast cancer and their children: Initial results regarding the effectiveness of the family oriented oncological rehabilitation program “gemeinsam gesund werden”. Prax. Kinderpsychol. Kinderpsychiatr. 2010, 59, 333–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möller, B.; Barkmann, C.; Krattenmacher, T.; Kühne, F.; Bergelt, C.; Beierlein, V.; Ernst, J.; Brähler, E.; Flechtner, H.-H.; Herzog, W.; et al. Children of Cancer Patients: Prevalence and Predictors of Emotional and Behavioral Problems. Cancer 2014, 120, 2361–2370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Lipsitz, O.; Nasri, F.; Lui, L.M.W.; Gill, H.; Phan, L.; Chen-Li, D.; Iacobucci, M.; Ho, R.; Majeed, A.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Mental Health in the General Population: A Systematic Review. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 277, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, J.; Butini, L.; Pauletto, P.; Lehmkuhl, K.; Stefani, C.; Bolan, M.; Guerra, E.; Dick, B.; Canto, G.; Massignan, C. Mental Health Effects Prevalence in Children and Adolescents during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs. 2022, 19, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, R. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A Research Note. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 1997, 38, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohbeck, A.; Schultheiß, J.; Petermann, F.; Petermann, U. Die Deutsche Selbstbeurteilungsversion Des Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ-Deu-S). Diagnostica 2015, 61, 222–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woerner, W.; Becker, A.; Rothenberger, A. Normative Data and Scale Properties of the German Parent SDQ. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2004, 13 (Suppl. S2), II3–II10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janitza, S.; Klipker, K.; Hölling, H. Age-Specific Norms and Validation of the German SDQ Parent Version Based on a Nationally Representative Sample (KiGGS). Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020, 29, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneewind, K.A.; Beckmann, M.; Hecht-Jackl, A. Das FK-Testsystem. Das Familienklima Aus Der Sichtweise Der Eltern Und Der Kinder. Forschungsberichte Aus Dem Institutsbereich Persönlichkeitspsychologie Und Psychodiagnostik, Nr. 8.1; Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität: Muenchen, Germany, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson, E.H.; Erikson, J.M. The Life Cycle Completed (Extended Version); W. W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 1998; ISBN 978-0-393-34743-2. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, D. The Eight Stages of Psychosocial Protective Development: Developmental Psychology. J. Behav. Brain Sci. 2018, 8, 369–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaronson, N.K.; Ahmedzai, S.; Bergman, B.; Bullinger, M.; Cull, A.; Duez, N.J.; Filiberti, A.; Flechtner, H.; Fleishman, S.B.; de Haes, J.C. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: A Quality-of-Life Instrument for Use in International Clinical Trials in Oncology. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1993, 85, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gräfe, K.; Zipfel, S.; Herzog, W.; Löwe, B. Screening Psychischer Störungen Mit Dem “Gesundheitsfragebogen Für Patienten (PHQ-D)”. Diagnostica 2004, 50, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B. The PHQ-9: Validity of a Brief Depression Severity Measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herschbach, P.; Marten-Mittag, B.; Henrich, G. Revision Und Psychometrische Prüfung Des Fragebogens Zur Belastung von Krebskranken (FBK-R23). Z. Für Med. Psychol. 2003, 12, 69–76. [Google Scholar]

- Book, K.; Marten-Mittag, B.; Henrich, G.; Dinkel, A.; Scheddel, P.; Sehlen, S.; Haimerl, W.; Schulte, T.; Britzelmeir, I.; Herschbach, P. Distress Screening in Oncology-Evaluation of the Questionnaire on Distress in Cancer Patients-Short Form (QSC-R10) in a German Sample. Psychooncology 2011, 20, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalgard, O.S.; Sørensen, T.; Sandanger, I.; Brevik, J.I. Psychiatric Interventions for Prevention of Mental Disorders. A Psychosocial Perspective. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care 1996, 12, 604–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. Released 2013 IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows; IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, R Foundation for Statistical Computing; R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2021.

- Wickham, H. ggplot2; Use R; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; ISBN 978-3-319-24275-0. [Google Scholar]

- Landi, G.; Duzen, A.; Patterson, P.; McDonald, F.E.J.; Crocetti, E.; Grandi, S.; Tossani, E. Illness Unpredictability and Psychosocial Adjustment of Adolescent and Young Adults Impacted by Parental Cancer: The Mediating Role of Unmet Needs. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacob, L.; Kalder, M.; Kostev, K. Incidence of Depression and Anxiety among Women Newly Diagnosed with Breast or Genital Organ Cancer in Germany. Psychooncology 2017, 26, 1535–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breidenbach, C.; Heidkamp, P.; Hiltrop, K.; Pfaff, H.; Enders, A.; Ernstmann, N.; Kowalski, C. Prevalence and Determinants of Anxiety and Depression in Long-Term Breast Cancer Survivors. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puigpinós-Riera, R.; Graells-Sans, A.; Serral, G.; Continente, X.; Bargalló, X.; Domènech, M.; Espinosa-Bravo, M.; Grau, J.; Macià, F.; Manzanera, R.; et al. Anxiety and Depression in Women with Breast Cancer: Social and Clinical Determinants and Influence of the Social Network and Social Support (DAMA Cohort). Cancer Epidemiol. 2018, 55, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inhestern, L.; Beierlein, V.; Bultmann, J.C.; Möller, B.; Romer, G.; Koch, U.; Bergelt, C. Anxiety and Depression in Working-Age Cancer Survivors: A Register-Based Study. BMC Cancer 2017, 17, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geue, K.; Brähler, E.; Faller, H.; Härter, M.; Schulz, H.; Weis, J.; Koch, U.; Wittchen, H.-U.; Mehnert, A. Prevalence of Mental Disorders and Psychosocial Distress in German Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Patients (AYA). Psychooncology 2018, 27, 1802–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graugaard, C.; Sperling, C.D.; Hølge-Hazelton, B.; Boisen, K.A.; Petersen, G.S. Sexual and Romantic Challenges among Young Danes Diagnosed with Cancer: Results from a Cross-Sectional Nationwide Questionnaire Study. Psychooncology 2018, 27, 1608–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Duan, Z.; Ma, Z.; Mao, Y.; Li, X.; Wilson, A.; Qin, H.; Ou, J.; Peng, K.; Zhou, F.; et al. Epidemiology of Mental Health Problems among Patients with Cancer during COVID-19 Pandemic. Transl. Psychiatry 2020, 10, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehnert, A.; Koch, U.; Schulz, H.; Wegscheider, K.; Weis, J.; Faller, H.; Keller, M.; Brähler, E.; Härter, M. Prevalence of Mental Disorders, Psychosocial Distress and Need for Psychosocial Support in Cancer Patients—Study Protocol of an Epidemiological Multi-Center Study. BMC Psychiatry 2012, 12, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banz-Jansen, C.; Heinrichs, A.; Hedderich, M.; Waldmann, A.; Dittmer, C.; Wedel, B.; Mebes, I.; Diedrich, K.; Fischer, D. Characteristics and Therapy of Premenopausal Patients with Early-Onset Breast Cancer in Germany. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2012, 286, 489–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, S.; Perveen, S.; Iqbal, M.; Ahmed, T.; Moula Bux, K.; Jafri, S.N.A. Epidemiology of Carcinoma Breast in Young Adolescence Women. Cureus 2022, 14, e23683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anastasiadi, Z.; Lianos, G.D.; Ignatiadou, E.; Harissis, H.V.; Mitsis, M. Breast Cancer in Young Women: An Overview. Updat. Surg. 2017, 69, 313–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radecka, B.; Litwiniuk, M. Breast Cancer in Young Women. Ginekol. Pol. 2016, 87, 659–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammersen, F.; Pursche, T.; Fischer, D.; Katalinic, A.; Waldmann, A. Psychosocial and Family-Centered Support among Breast Cancer Patients with Dependent Children. Psychooncology 2021, 30, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lidington, E.; Giesinger, J.M.; Janssen, S.H.M.; Tang, S.; Beardsworth, S.; Darlington, A.-S.; Starling, N.; Szucs, Z.; Gonzalez, M.; Sharma, A.; et al. Identifying Health-Related Quality of Life Cut-off Scores That Indicate the Need for Supportive Care in Young Adults with Cancer. Qual. Life Res. 2022, 31, 2717–2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Zhao, J.; Nogueira, L.; Han, X.; Fan, Q.; Yabroff, K.R. Associations of Parental Cancer with School Absenteeism, Medical Care Unaffordability, Health Care Use, and Mental Health Among Children. JAMA Pediatr. 2022, 176, 593–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inhestern, L.; Johannsen, L.M.; Bergelt, C. Families Affected by Parental Cancer: Quality of Life, Impact on Children and Psychosocial Care Needs. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 765327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiss, F.; Meyrose, A.-K.; Otto, C.; Lampert, T.; Klasen, F.; Ravens-Sieberer, U. Socioeconomic Status, Stressful Life Situations and Mental Health Problems in Children and Adolescents: Results of the German BELLA Cohort-Study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0213700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Kaman, A.; Otto, C.; Adedeji, A.; Napp, A.-K.; Becker, M.; Blanck-Stellmacher, U.; Löffler, C.; Schlack, R.; Hölling, H.; et al. Seelische Gesundheit und psychische Belastungen von Kindern und Jugendlichen in der ersten Welle der COVID-19-Pandemie—Ergebnisse der COPSY-Studie. Bundesgesundheitsblatt—Gesundheitsforschung—Gesundheitsschutz 2021, 64, 1512–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinz, A.; Herzberg, P.Y.; Lordick, F.; Weis, J.; Faller, H.; Brähler, E.; Härter, M.; Wegscheider, K.; Geue, K.; Mehnert, A. Age and Gender Differences in Anxiety and Depression in Cancer Patients Compared with the General Population. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2019, 28, e13129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christner, N.; Essler, S.; Hazzam, A.; Paulus, M. Children’s Psychological Well-Being and Problem Behavior during the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Online Study during the Lockdown Period in Germany. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0253473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patrick, S.W.; Henkhaus, L.E.; Zickafoose, J.S.; Lovell, K.; Halvorson, A.; Loch, S.; Letterie, M.; Davis, M.M. Well-Being of Parents and Children During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A National Survey. Pediatrics 2020, 146, e2020016824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, A.; Lomma, C.; Chih, H.; Arto, C.; McDonald, F.; Patterson, P.; Willsher, P.; Reid, C. Psychosocial Consequences in Offspring of Women with Breast Cancer. Psychooncology 2020, 29, 517–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weis, S.; Koch, G.; Dieball, S.; von Klitzing, K.; Romer, G.; Lehmkuhl, U.; Bergelt, C.; Resch, F.; Flechtner, H.-H.; Keller, M.; et al. Alleinerziehend und krebskrank—Was macht das mit dem Kind? Psychische Symptome und Lebensqualität von Kindern aus Kind- und Elternperspektive. Psychother. Psychosom. Med. Psychol. 2012, 62, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenaar-Golan, V.; Hen, M. Do Parents’ Internal Processes and Feelings Contribute to the Way They Report Their Children’s Mental Difficulties on the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ)? Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2022, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, F.M.; Brandt, P.A.; Cochrane, B.B.; Griffith, K.A.; Grant, M.; Haase, J.E.; Houldin, A.D.; Post-White, J.; Zahlis, E.H.; Shands, M.E. The Enhancing Connections Program: A 6-State Randomized Clinical Trial of a Cancer Parenting Program. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2015, 83, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Statistics | Values |

|---|---|---|

| Age of mother at diagnosis | N | 485 |

| Mean (SD *) | 40.3 (5.34) | |

| Range | 18–54 | |

| Tumour size (TNM T-category) | N | 443 |

| Tis | (in %) | 8.4 |

| T0 | 36.1 | |

| T1 | 36.3 | |

| T2 | 15.8 | |

| T3 | 3.4 | |

| T4 | 0 | |

| Lymph node status (TNM N-category) | N | 425 |

| N0 | (in %) | 72.9 |

| N1 | 19.5 | |

| N2 | 6.1 | |

| N3 | 1.4 | |

| Grading | N | 495 |

| G1 | (in %) | 6.3 |

| G2 | 39.1 | |

| G3 | 54.6 | |

| Type of surgery | N | 496 |

| Breast-conserving | (in %) | 57.5 |

| Mastectomy without reconstruction | 11.5 | |

| Mastectomy/other with reconstruction | 31.0 | |

| Radiotherapy | N | 496 |

| Yes | (in %) | 81.7 |

| No | 18.3 | |

| Chemotherapy | N | 496 |

| Yes | (in %) | 85.9 |

| No | 14.1 | |

| Endocrine therapy | N | 496 |

| Yes | (in %) | 71.2 |

| No | 28.8 | |

| Waiting time in months for the rehab program to start | N | 492 |

| ≤6 months | (in %) | 4.1 |

| 7–12 months | 39.2 | |

| 13–18 months | 49.8 | |

| >18 months | 6.9 | |

| Factor ‘psychosocial well-being’ (factor analysis) | N | 488 |

| Mean (SD *) | 61.1 (18.2) | |

| Range | 18.3–98.5 |

| Family Environment, Structure | Statistics | Values |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Children # | N | 495 |

| 1 | (in %) | 35.3 |

| 2 | 49.3 | |

| 3 | 13.1 | |

| ≥4 | 2.2 | |

| Partnership | N | 494 |

| Single | (in %) | 18.4 |

| Married | 65.8 | |

| Living apart/divorced | 14.8 | |

| Widowed | 1.0 | |

| Social Class Index (According to Deck and Roeckelein) | N | 494 |

| Middle class | (in %) | 35.0 |

| Upper Class | 65.0 | |

| Social Support (3-item Oslo Social Support Scale) | N | 481 |

| Mean (SD *) | 11.0 (1.86) | |

| Range | 5–14 | |

| Little social support (3–8) | (in %) | 8.9 |

| Moderate social support (9–11) | 50.1 | |

| Strong social support (12–14) | 41.0 | |

| Family climate | N | 491 |

| Mean (SD *) | 68.1 (14.5) | |

| Range | 19–96 | |

| Normal (>55.6–100) | (in %) | 79.6 |

| Small deficits (>48.2–55.6) | 9.8 | |

| Strong deficits (0–48.2) | 10.6 |

| Characteristics | Statistics | Values |

|---|---|---|

| Ageof the eldest child | N | 496 |

| Mean (SD *) | 8.58 (2.78) | |

| Range | 4–15 | |

| Age categories by Erikson | N | 496 |

| Playing age (4–5 years old) | (in %) | 15.7 |

| School age (6–11 years old) | 67.5 | |

| Adolescence (12–17 years old) | 16.7 | |

| Sex | N | 493 |

| Boys | (in %) | 46.5 |

| Girls | 53.5 | |

| Sibling status | N | 495 |

| Single child | (in %) | 35.4 |

| At least one sibling | 64.6 |

| Children in Our Study | Norm Sample Woerner et al., 2002 [14] | Paediatric Outpatient Patients Hellweg, 2004, as Reported in Woerner et al. [14] | Paediatric Rehabilitation Patients Oepem et al., 2003, as Reported in Woerner et al. [14] | Paediatric Psychiatry Patients Becker et al., 2004, as Reported in Woerner et al. [14] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | 496 | 930 | 995 | 1049 | 639 |

| Mean age in years | 8.6 | 10.7 | 9.9 | 11.4 | 10.5 |

| Proportion of boys (%) | 46.5 | 50.2 | 52.4 | 56.0 | 71.7 |

| Total difficulties score | |||||

| Mean points | 10.4 | 8.13 | 8.18 | 16.8 | 16.2 |

| % ≥16 | 18.8 | 10.0 | 12.8 | 56.8 | 53.1 |

| Emotional problems | |||||

| Mean points | 3.08 | 1.53 | 2.14 | 4.19 | 3.67 |

| % ≥5 | 25.6 | 7.7 | 14.1 | 45 | 35.8 |

| Conduct problems | |||||

| Mean points | 2.04 | 1.82 | 1.79 | 3.51 | 3.59 |

| % ≥5 | 10.1 | 6.6 | 7.2 | 31.0 | 32.4 |

| Hyperactivity | |||||

| Mean points | 3.77 | 3.19 | 3.02 | 5.41 | 5.72 |

| % ≥7 | 15.3 | 9.8 | 11.8 | 35.8 | 42.4 |

| Peer problems | |||||

| Mean points | 1.49 | 1.59 | 1.23 | 3.66 | 3.17 |

| % ≥5 | 7.7 | 7.0 | 4.7 | 36.2 | 27.1 |

| Prosocial behaviour | |||||

| Mean points | 7.86 | 7.55 | 8.23 | 7.39 | 6.69 |

| % ≥4 | 6.0 | 7.1 | 2.8 | 8.2 | 17.5 |

| Non-Standardised Regression Coefficient Beta | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Contextual factors | ||

| Rehab stay before or during COVID-19 pandemic (reference before versus during) | 0.274 | 0.607 |

| Waiting time between diagnosis and rehab stay (ref. <6, vs. 6–12 or >12 months) | −0.555 | 0.282 |

| Children’s characteristics | ||

| Sex of the eldest child (ref. male vs. female) | −1.63 | 0.002 |

| Age of the eldest child in years (4–15) | 0.008 | 0.937 |

| Descriptors of family life and social support | ||

| Number of children in household (1–5) | −0.786 | 0.031 |

| Single parenting (ref. yes vs. no) | −0.720 | 0.266 |

| Family environment (score range: 0–100; low values indicate problematic environment: the higher the better) | −0.109 | <0.001 |

| Social support (score range: 3–14; low values indicate low support: the higher the better) | −0.031 | 0.827 |

| Social status (ref. middle vs. high) | −0.361 | 0.521 |

| Characteristics of the mothers with early-onset breast cancer | ||

| Age in years at diagnosis | −0.058 | 0.280 |

| Received systematic anticancer treatment (chemotherapy) (ref. no vs. yes) | 0.391 | 0.644 |

| Received radiotherapy (ref. no vs. yes) | 0.456 | 0.486 |

| Received endocrine therapy (ref. no vs. yes) | 0.543 | 0.337 |

| Psychosocial well-being (score range: 0–100; low values indicate low psychosocial well-being: the higher the better) | −0.055 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schliemann, A.; Teroerde, A.; Beurer, B.; Hammersen, F.; Fischer, D.; Katalinic, A.; Labohm, L.; Strobel, A.M.; Waldmann, A. Reduced Psychosocial Well-Being among the Children of Women with Early-Onset Breast Cancer. Curr. Oncol. 2023, 30, 10057-10074. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30120731

Schliemann A, Teroerde A, Beurer B, Hammersen F, Fischer D, Katalinic A, Labohm L, Strobel AM, Waldmann A. Reduced Psychosocial Well-Being among the Children of Women with Early-Onset Breast Cancer. Current Oncology. 2023; 30(12):10057-10074. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30120731

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchliemann, Antje, Alica Teroerde, Bjoern Beurer, Friederike Hammersen, Dorothea Fischer, Alexander Katalinic, Louisa Labohm, Angelika M. Strobel, and Annika Waldmann. 2023. "Reduced Psychosocial Well-Being among the Children of Women with Early-Onset Breast Cancer" Current Oncology 30, no. 12: 10057-10074. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30120731

APA StyleSchliemann, A., Teroerde, A., Beurer, B., Hammersen, F., Fischer, D., Katalinic, A., Labohm, L., Strobel, A. M., & Waldmann, A. (2023). Reduced Psychosocial Well-Being among the Children of Women with Early-Onset Breast Cancer. Current Oncology, 30(12), 10057-10074. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30120731