Local Treatment Efficacy for Single-Area Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Unknown Primary Site

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Varadhachary, G.R.; Raber, M.N. Cancer of Unknown Primary Site. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 757–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fizazi, K.; Greco, F.A.; Pavlidis, N.; Daugaard, G.; Oien, K.; Pentheroudakis, G. ESMO Guidelines Committee Cancers of Unknown Primary Site: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow-Up. Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26 (Suppl. S5), v133–v138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavlidis, N.; Briasoulis, E.; Hainsworth, J.; Greco, F.A. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Management of Cancer of an Unknown Primary. Eur. J. Cancer 2003, 39, 1990–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavlidis, N.; Khaled, H.; Gaafar, R. A Mini Review on Cancer of Unknown Primary Site: A Clinical Puzzle for the Oncologists. J. Adv. Res. 2015, 6, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levi, F.; Te, V.C.; Erler, G.; Randimbison, L.; La Vecchia, C. Epidemiology of Unknown Primary Tumours. Eur. J. Cancer 2002, 38, 1810–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrović, D.; Muzikravić, L.; Jovanović, D. Metastases of Unknown Origin—Principles of Diagnosis and Treatment. Med. Pregl. 2007, 60, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- NCCN. Practice Guidelines for Occult Primary Tumors (Ver 2024). Available online: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/occult.pdf (accessed on 19 July 2023).

- Losa, F.; Iglesias, L.; Pané, M.; Sanz, J.; Nieto, B.; Fusté, V.; de la Cruz-Merino, L.; Concha, Á.; Balañá, C.; Matías-Guiu, X. 2018 Consensus Statement by the Spanish Society of Pathology and the Spanish Society of Medical Oncology on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Cancer of Unknown Primary. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2018, 20, 1361–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Japan Practice Guidelines for Occult Primary Tumors (Ver 2, 2018). Available online: https://minds.jcqhc.or.jp/docs/gl_pdf/G0001078/4/Carcinoma_of_Unknown_Primary.pdf (accessed on 19 July 2023).

- Matsubara, N.; Mukai, H.; Nagai, S.; Itoh, K. Review of Primary Unknown Cancer: Cases Referred to the National Cancer Center Hospital East. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 15, 578–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemminki, K.; Bevier, M.; Hemminki, A.; Sundquist, J. Survival in Cancer of Unknown Primary Site: Population-Based Analysis by Site and Histology. Ann. Oncol. 2012, 23, 1854–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, V.; Kattimani, K.; Manohar, V.; Ravindranath, S. Inguinal Lymph Node Squamous Cell Carcinoma of Unknown Primary Site: A Case Report. J. Surg. Oper. Care 2016, 1, 208. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuyama, S.; Nakafusa, Y.; Tanaka, M.; Yoda, Y.; Mori, D.; Miyazaki, K. Iliac Lymph Node Metastasis of an Unknown Primary Tumor: Report of a Case. Surg. Today 2006, 36, 655–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.-H.; Yeh, S.-D.; Chiou, J.-F.; Lin, Y.-H.; Chang, C.-W. Optimum Treatment for Primary Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Pelvic Retroperitoneum. J. Exp. Clin. Med. 2011, 3, 304–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, B.O.; Zhu, J.; Chen, L.U. Squamous Cell Carcinoma of Unknown Primary Site Presenting with an Abdominal Wall Lesion as the Primary Symptom: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Oncol. Lett. 2015, 10, 2161–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Briasoulis, E.; Kalofonos, H.; Bafaloukos, D.; Samantas, E.; Fountzilas, G.; Xiros, N.; Skarlos, D.; Christodoulou, C.; Kosmidis, P.; Pavlidis, N. Carboplatin plus Paclitaxel in Unknown Primary Carcinoma: A Phase II Hellenic Cooperative Oncology Group Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2000, 18, 3101–3107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huebner, G.; Link, H.; Kohne, C.H.; Stahl, M.; Kretzschmar, A.; Steinbach, S.; Folprecht, G.; Bernhard, H.; Al-Batran, S.E.; Schoffski, P.; et al. Paclitaxel and Carboplatin vs Gemcitabine and Vinorelbine in Patients with Adeno- or Undifferentiated Carcinoma of Unknown Primary: A Randomised Prospective Phase II Trial. Br. J. Cancer 2009, 100, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, H.; Kurata, T.; Takiguchi, Y.; Arai, M.; Takeda, K.; Akiyoshi, K.; Matsumoto, K.; Onoe, T.; Mukai, H.; Matsubara, N.; et al. Randomized Phase II Trial Comparing Site-Specific Treatment Based on Gene Expression Profiling with Carboplatin and Paclitaxel for Patients with Cancer of Unknown Primary Site. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 570–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haratani, K.; Hayashi, H.; Takahama, T.; Nakamura, Y.; Tomida, S.; Yoshida, T.; Chiba, Y.; Sawada, T.; Sakai, K.; Fujita, Y.; et al. Clinical and Immune Profiling for Cancer of Unknown Primary Site. J. Immunother. Cancer 2019, 7, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGrail, D.J.; Pilié, P.G.; Rashid, N.U.; Voorwerk, L.; Slagter, M.; Kok, M.; Jonasch, E.; Khasraw, M.; Heimberger, A.B.; Lim, B.; et al. High Tumor Mutation Burden Fails to Predict Immune Checkpoint Blockade Response across All Cancer Types. Ann. Oncol. 2021, 32, 661–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanizaki, J.; Yonemori, K.; Akiyoshi, K.; Minami, H.; Ueda, H.; Takiguchi, Y.; Miura, Y.; Segawa, Y.; Takahashi, S.; Iwamoto, Y.; et al. Open-Label Phase II Study of the Efficacy of Nivolumab for Cancer of Unknown Primary. Ann. Oncol. 2022, 33, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Pathological Type | Cases (n) | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Adenocarcinoma | 141 | 62.1 |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 36 | 15.9 |

| Poorly/undifferentiated carcinoma | 19 | 8.3 |

| Neuroendocrine carcinoma | 15 | 6.6 |

| Sarcoma | 7 | 3.0 |

| Unknown | 9 | 4.0 |

| Case (n) | (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | –49 | 9 | 25.0 |

| 50–69 | 17 | 47.2 | |

| 70– | 10 | 27.8 | |

| PS | 0 | 22 | 61.1 |

| 1 | 14 | 38.9 | |

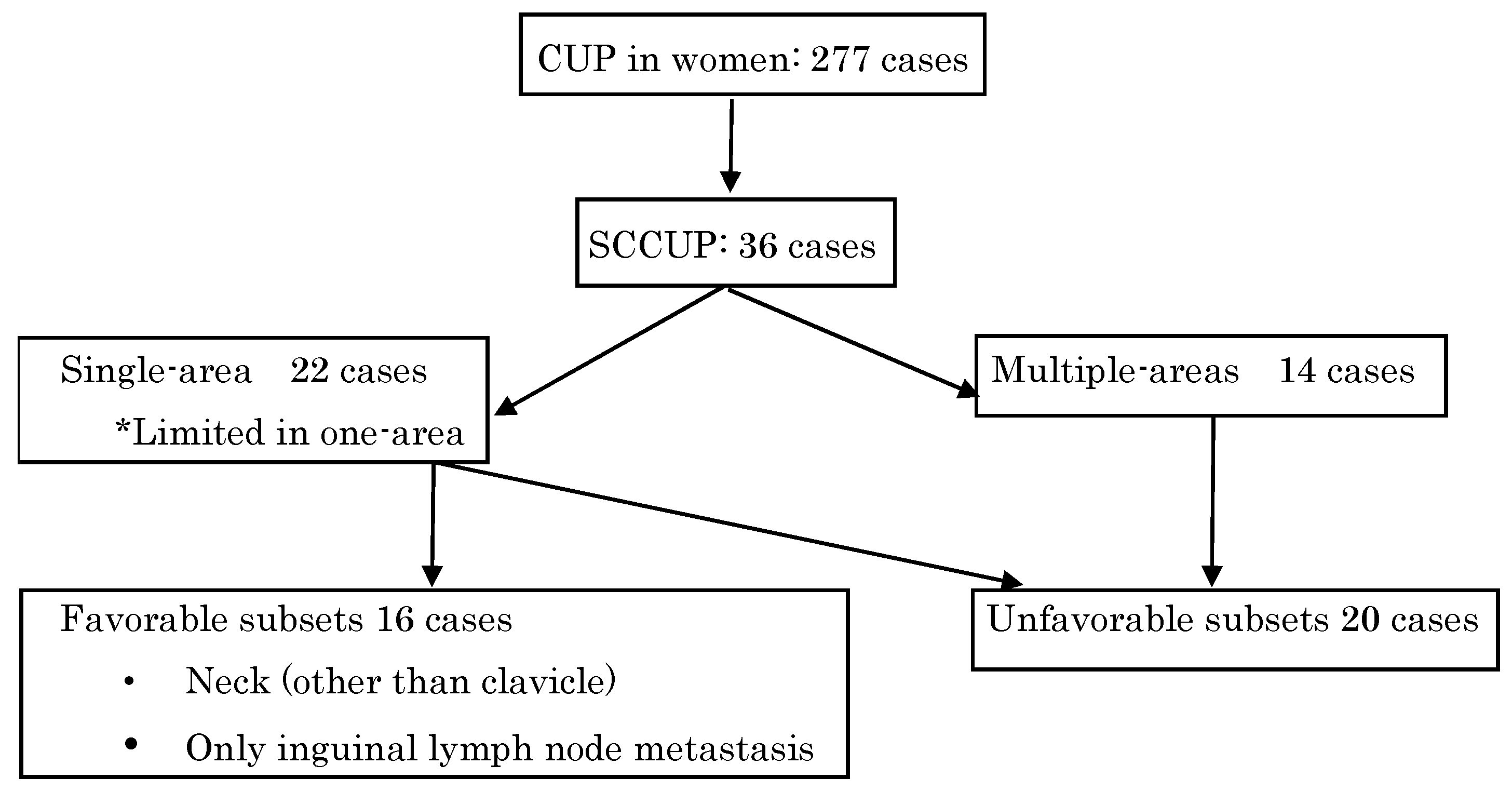

| Lesion | Single-area | 22 | 61.1 |

| Multi-area | 14 | 38.9 | |

| Category | Favorable subset | 16 | 44.4 |

| Unfavorable subset | 20 | 55.6 |

| Case | Year | PS | Lesion | Therapy | Prognosis | Department of Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 80 | 1 | Neck LN | Palliative RT | DOD 4 M | Radiation Therapy |

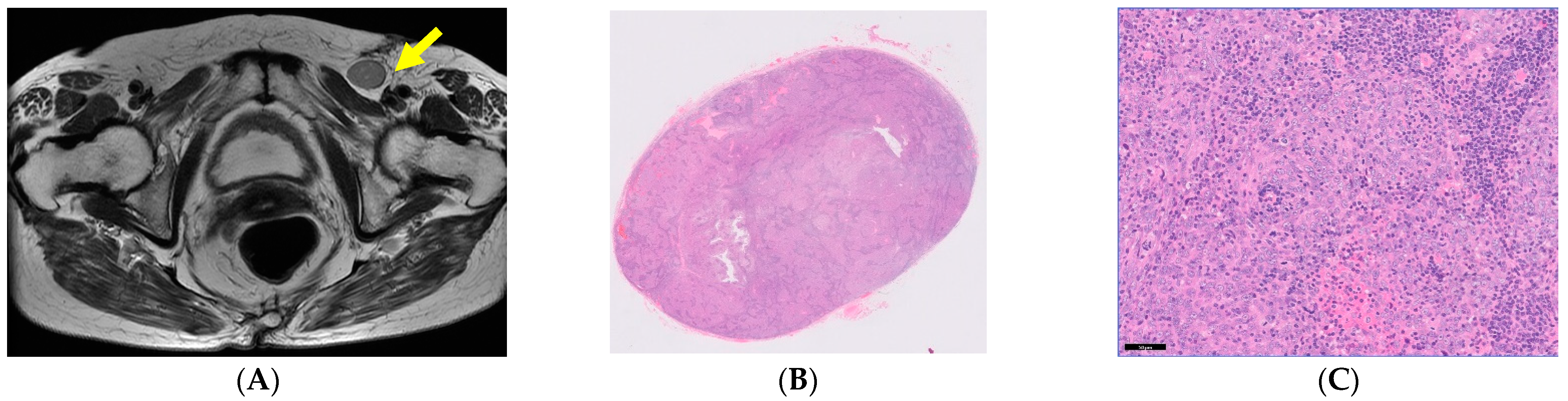

| 2 | 80 | 0 | Inginal LN | Inginal LND | NED | Gynecology |

| 3 | 79 | 0 | Neck LN | LND | NED | Medical Oncology |

| 4 | 77 | 0 | Neck LN | LND + RT | NED | Orthopedic Surgery |

| 5 | 76 | 0 | Neck LN | LND | NED | Orthopedic Surgery |

| 6 | 73 | 0 | Neck LN | RT | DOD 10 M Laryngeal edema | Orthopedic Surgery |

| 7 | 72 | 0 | Neck LN | CCRT | NED | Medical Oncology |

| 8 | 72 | 0 | Neck LN | RT | NED | Medical Oncology |

| 9 | 68 | 0 | Neck LN | RT | NED | Orthopedic Surgery |

| 10 | 68 | 0 | Neck LN | NAC + CCRT | NED | Orthopedic Surgery |

| 11 | 68 | 0 | Neck LN | LND | NED | Orthopedic Surgery |

| 12 | 68 | 0 | Neck LN | LND + RT | NED | Orthopedic Surgery |

| 13 | 66 | 0 | Neck LN | LND + RT | NED | Orthopedic Surgery |

| 14 | 65 | 0 | Neck LN | LND + RT | NED | Orthopedic Surgery |

| 15 | 54 | 0 | Neck LN | LND + tonsillectomy | NED | Medical Oncology |

| 16 | 50 | 0 | Neck LN | LND | NED | Orthopedic Surgery |

| Case | Year | PS | Lesion | Therapy | Prognosis (Year/Months) | Department of Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 79 | 0 | Iliac muscle~ psoas major muscle | CCRT | Death from gastric cancer | Gastroenterology |

| 2 | 55 | 0 | Rectum | Ope | NED 2y1m | Gastroenterology |

| 3 | 53 | 1 | Pelvic bone | Chemo + RT | DOD 3y8m | Orthopedic Oncology |

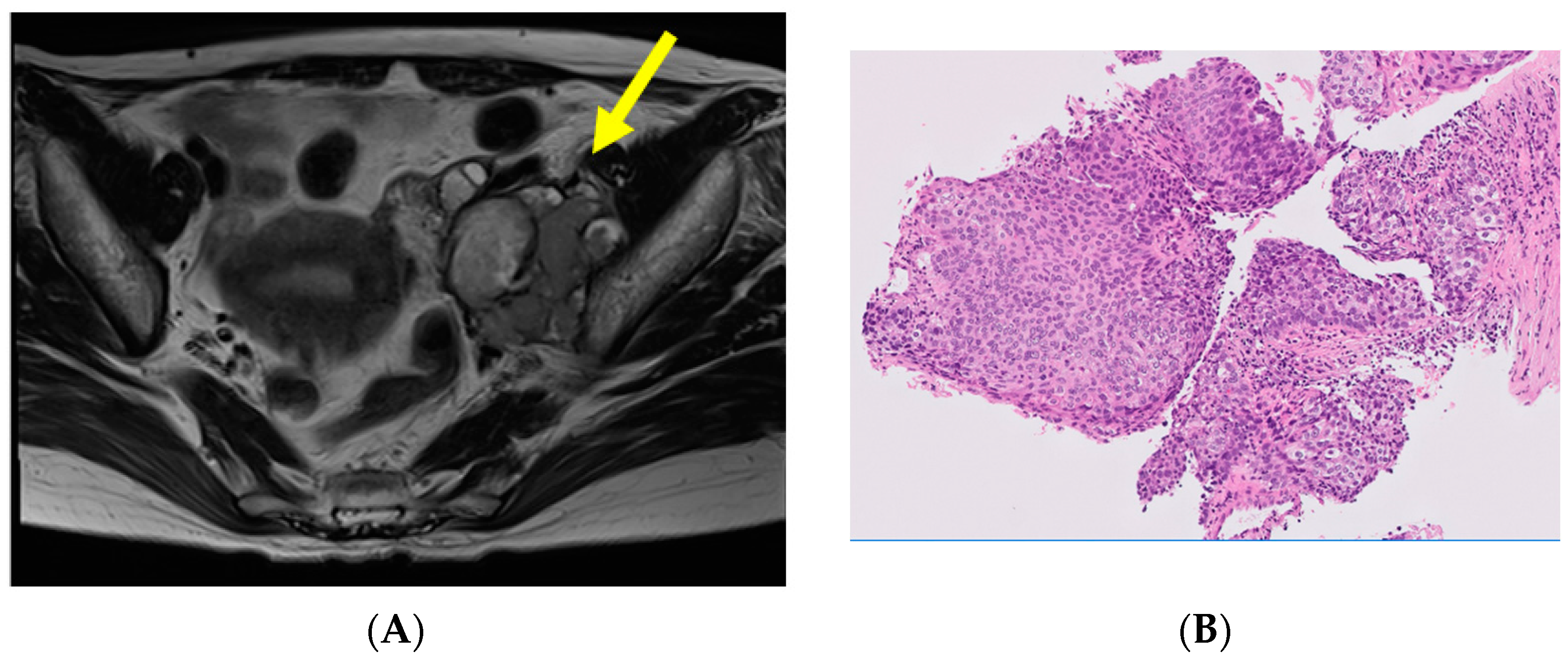

| 4 | 48 | 0 | Lt pelvic lymph node~ psoas major muscle | CCRT | NED 1y5m | Gynecology |

| 5 | 39 | 0 | Rt pelvic lymph node | Chemo + CCRT | DOD 2y11m | Medical Oncology |

| 6 | 31 | 0 | Lt pelvic lymph node | CCRT | NED 6y6m | Gynecology |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kurita, T.; Yunokawa, M.; Tanaka, Y.; Okamoto, K.; Kanno, M.; Fusegi, A.; Omi, M.; Netsu, S.; Nomura, H.; Tonooka, A.; et al. Local Treatment Efficacy for Single-Area Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Unknown Primary Site. Curr. Oncol. 2023, 30, 9327-9334. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30100674

Kurita T, Yunokawa M, Tanaka Y, Okamoto K, Kanno M, Fusegi A, Omi M, Netsu S, Nomura H, Tonooka A, et al. Local Treatment Efficacy for Single-Area Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Unknown Primary Site. Current Oncology. 2023; 30(10):9327-9334. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30100674

Chicago/Turabian StyleKurita, Tomoko, Mayu Yunokawa, Yuji Tanaka, Kota Okamoto, Motoko Kanno, Atsushi Fusegi, Makiko Omi, Sachiho Netsu, Hidetaka Nomura, Akiko Tonooka, and et al. 2023. "Local Treatment Efficacy for Single-Area Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Unknown Primary Site" Current Oncology 30, no. 10: 9327-9334. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30100674

APA StyleKurita, T., Yunokawa, M., Tanaka, Y., Okamoto, K., Kanno, M., Fusegi, A., Omi, M., Netsu, S., Nomura, H., Tonooka, A., & Kanao, H. (2023). Local Treatment Efficacy for Single-Area Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Unknown Primary Site. Current Oncology, 30(10), 9327-9334. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30100674