A Process Evaluation of Intervention Delivery for a Cancer Survivorship Rehabilitation Clinical Trial Conducted during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview

2.2. Description of Intervention

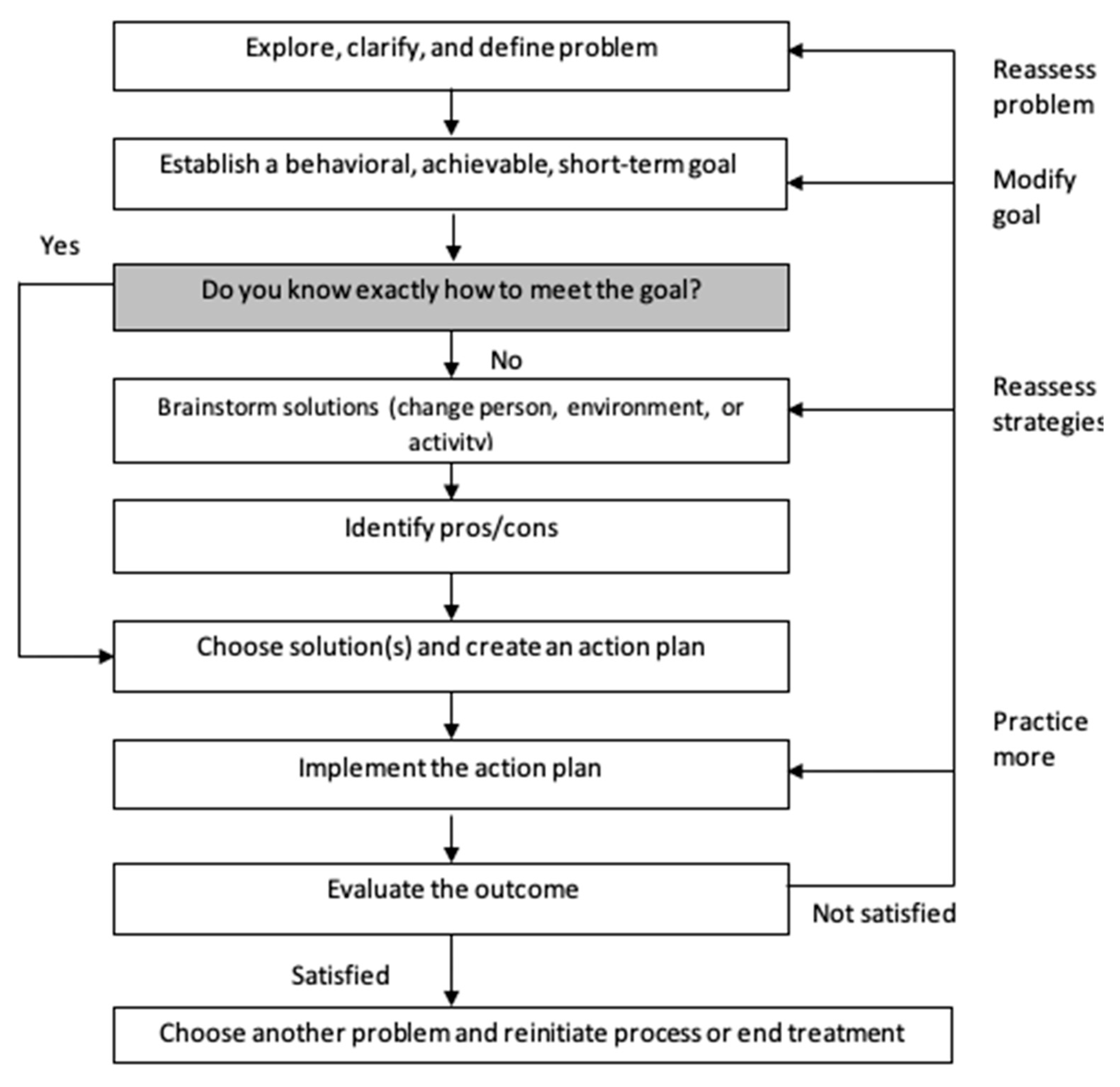

2.2.1. Behavioral Activation/Problem-Solving (BA/PS)

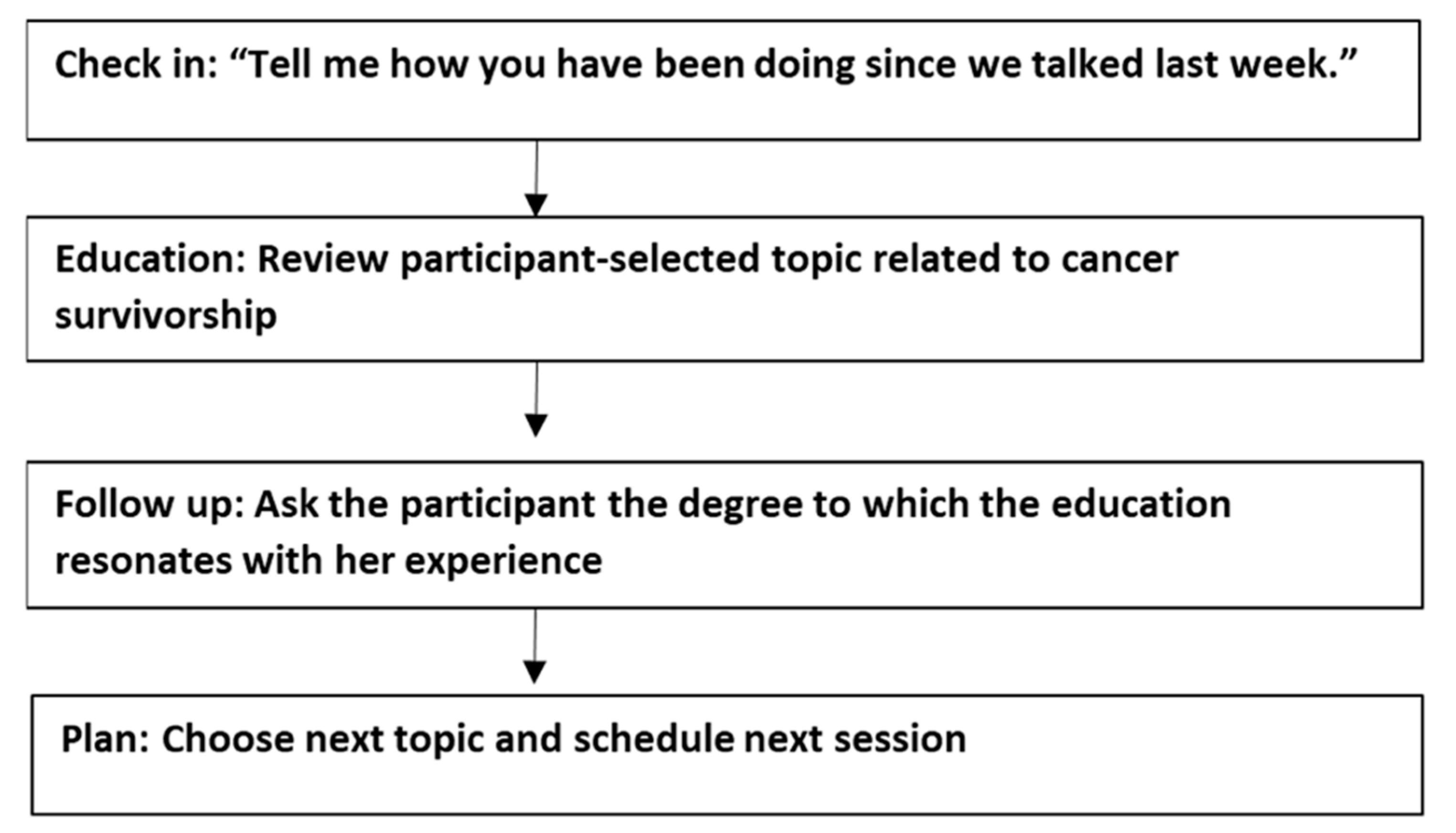

2.2.2. Attention Control

2.3. Participants

2.4. Coaches

2.5. Sources of Data

2.5.1. Fidelity Ratings

2.5.2. Perceived Benefits

2.5.3. Feedback from Coaches and Participants

2.6. Analysis

3. Results

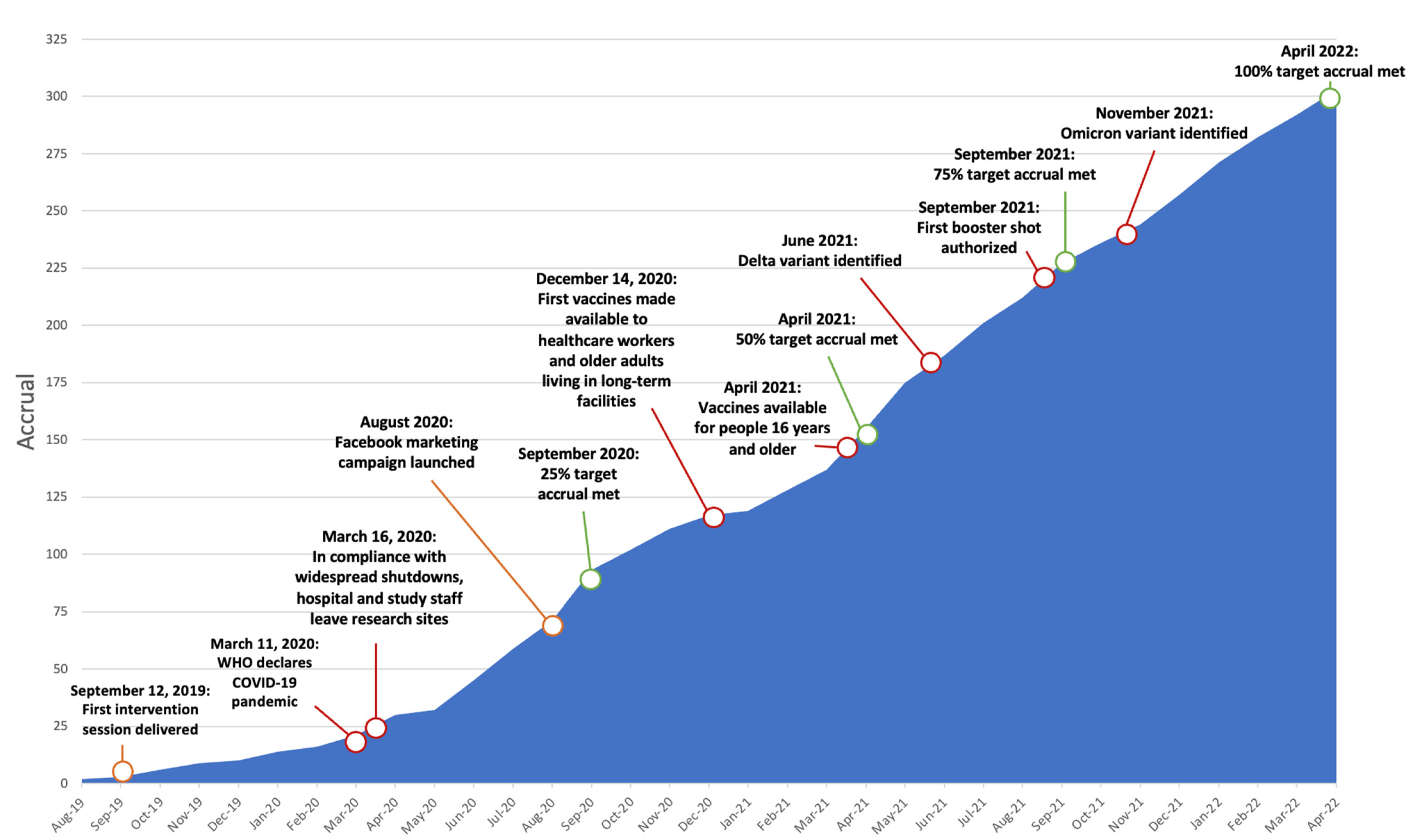

3.1. Participants

3.2. Fidelity Ratings

3.3. Perceived Benefit

3.4. Feedback from Coaches

3.4.1. Behavioral Activation/Problem-Solving (BA/PS)

Structured Process to Approach Challenges with Creativity

Making Small and Observable Progress toward Goals

Translation of Skills through Participant-Directed Problem-Solving and Reflection

3.4.2. Attention Control

Perceived Relevance, Utility, and Timeliness of Educational Content

Opportunity for Social Support and Contact

3.4.3. Context of a Clinical Trial during a Pandemic

4. Discussion

4.1. Fidelity Ratings

4.2. Perceived Benefit

4.3. Coach Feedback

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ness, K.K.; Wall, M.M.; Oakes, J.M.; Robison, L.L.; Gurney, J.G. Physical performance limitations and participation restrictions among cancer survivors: A population-based study. Ann. Epidemiol. 2006, 16, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, R.; Wang, L.; Bu, X.; Wang, W.; Zhu, J. Unmet supportive care needs of breast cancer survivors: A systematic scoping review. BMC Cancer 2023, 23, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egan, M.Y.; McEwen, S.; Sikora, L.; Chasen, M.; Fitch, M.; Eldred, S. Rehabilitation following cancer treatment. Disabil. Rehabil. 2013, 35, 2245–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loh, S.Y.; Musa, A.N. Methods to improve rehabilitation of patients following breast cancer surgery: A review of systematic reviews. Breast Cancer (Dove Med. Press) 2015, 7, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loubani, K.; Schreuer, N.; Kizony, R. Telerehabilitation for Managing Daily Participation among Breast Cancer Survivors during COVID-19: A Feasibility Study. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boland, L.; Bennett, K.; Cuffe, S.; Gleeson, N.; Grant, C.; Kennedy, J.; Connolly, D. Cancer survivors’ experience of OptiMal, a 6-week, occupation-based, self-management intervention. Br. J. Occup. Ther. 2019, 82, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopko, D.R.; Lejuez, C.W.; Ruggiero, K.J.; Eifert, G.H. Contemporary behavioral activation treatments for depression: Procedures, principles, and progress. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2003, 23, 699–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegel, M.T.; Arean, P.A. Problem-Solving Treatment for Primary Care: A Treatment Manual for Depression, Project IMPACT; Dartmouth College: Hanover, NH, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hegel, M.T.; Lyons, K.D.; Hull, J.G.; Kaufman, P.; Urquhart, L.; Li, Z.; Ahles, T.A. Feasibility study of a randomized controlled trial of a telephone-delivered problem-solving-occupational therapy intervention to reduce participation restrictions in rural breast cancer survivors undergoing chemotherapy. Psychooncology 2011, 20, 1092–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, K.D.; Hull, J.G.; Kaufman, P.A.; Li, Z.; Seville, J.; Ahles, T.A.; Kornblith, A.B.; Hegel, M.T. Development and initial evaluation of a telephone-delivered, Behavioral Activation and Problem-solving Treatment Program to address functional goals of breast cancer survivors. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 2015, 33, 199–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheville, A.L.; Kornblith, A.B.; Basford, J.R. An examination of the causes for the underutilization of rehabilitation services among people with advanced cancer. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2011, 90, S27–S37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stubblefield, M.D. The Underutilization of Rehabilitation to Treat Physical Impairments in Breast Cancer Survivors. PM&R 2017, 9, S317–S323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, C.J.; Hegel, M.T.; Bakitas, M.A.; Bruce, M.; Azuero, A.; Pisu, M.; Chamberlin, M.; Keene, K.; Rocque, G.; Ellis, D.; et al. Study protocol for a multisite randomised controlled trial of a rehabilitation intervention to reduce participation restrictions among female breast cancer survivors. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e036864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahn, E.A.; Beaumont, J.L.; Pilkonis, P.A.; Garcia, S.F.; Magasi, S.; DeWalt, D.A.; Cella, D. The PROMIS satisfaction with social participation measures demonstrated responsiveness in diverse clinical populations. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2016, 73, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, E.A.; Devellis, R.F.; Bode, R.K.; Garcia, S.F.; Castel, L.D.; Eisen, S.V.; Bosworth, H.B.; Heinemann, A.W.; Rothrock, N.; Cella, D.; et al. Measuring social health in the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS): Item bank development and testing. Qual. Life Res. 2010, 19, 1035–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medidata. COVID-19 and Clinical Trials: The Medidata Perspective. Available online: https://www.medidata.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/COVID19-Response4.0_Clinical-Trials_20200504_v3.2-1.pdf (accessed on 19 April 2023).

- Rentscher, K.E.; Zhou, X.; Small, B.J.; Cohen, H.J.; Dilawari, A.A.; Patel, S.K.; Bethea, T.N.; Van Dyk, K.M.; Nakamura, Z.M.; Ahn, J.; et al. Loneliness and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic in older breast cancer survivors and noncancer controls. Cancer 2021, 127, 3671–3679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabaczynski, A.; Bastas, D.; Whitehorn, A.; Trinh, L. Changes in physical activity and associations with quality of life among a global sample of cancer survivors during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Cancer Surviv. 2023, 17, 1191–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurgel, A.R.B.; Mingroni-Netto, P.; Farah, J.C.; de Brito, C.M.M.; Levin, A.S.; Brum, P.C. Determinants of Health and Physical Activity Levels Among Breast Cancer Survivors During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 624169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skivington, K.; Matthews, L.; Simpson, S.A.; Craig, P.; Baird, J.; Blazeby, J.M.; Boyd, K.A.; Craig, N.; French, D.P.; McIntosh, E.; et al. A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: Update of Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2021, 374, n2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejem, D.B.; Wechsler, S.; Gallups, S.; Khalidi, S.; Coffee-Dunning, J.; Montgomery, A.; Stevens, C.; Keene, K.; Rocque, G.; Chamberlin, M.; et al. Enhancing Efficiency and Reach Using Facebook to Recruit Breast Cancer Survivors for a Telephone-based Supportive Care Randomized Trial During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Clin. Oncol. Oncol. Pract. 2023, OP.23.00117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, M.; Baptiste, S.; Carswell, A.; McColl, M.A.; Polatajko, H.; Pollock, N. Canadian Occupational Performance Measure, 5th ed.; Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dimidjian, S.; Barrera, M.; Martell, C.; Munoz, R.F.; Lewinsohn, P.M. The origins and current status of Behavioral Activation Treatments for depression. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2011, 7, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundt, J.C.; Marks, I.M.; Shear, M.K.; Greist, J.H. The Work and Social Adjustment Scale: A simple measure of impairment in functioning. Br. J. Psychiatry 2002, 180, 461–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callahan, C.M.; Unverzagt, F.W.; Hui, S.L.; Perkins, A.J.; Hendrie, H.C. Six-item screener to identify cognitive impairment among potential subjects for clinical research. Med. Care 2002, 40, 771–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Occupational Therapy Association. Occupational Therapy Practice Framework: Domain and Process, 4th ed.; AOTA Press: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons, K.D.; Svensborn, I.A.; Kornblith, A.B.; Hegel, M.T. A content analysis of recovery strategies of breast cancer survivors enrolled in a goal-setting intervention. OTJR Occup. Particip. Health 2015, 35, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szanton, S.L.; Xue, Q.-L.; Leff, B.; Guralnik, J.; Wolff, J.L.; Tanner, E.K.; Boyd, C.; Thorpe, R.J., Jr.; Bishai, D.; Gitlin, L.N. Effect of a Biobehavioral Environmental Approach on Disability Among Low-Income Older Adults: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 2019, 179, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitlin, L.N.; Winter, L.; Dennis, M.P.; Hodgson, N.; Hauck, W.W. A biobehavioral home-based intervention and the well-being of patients with dementia and their caregivers: The COPE randomized trial. Jama 2010, 304, 983–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachiochi, P.D.; Weiner, S.P. Qualitative data collection and analysis. In Handbook of Research Methods in Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Rogelberg, S.G., Ed.; Blackwell Publishing: Malden, MA, USA, 2004; pp. 161–183. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M.Q. Enhancing the quality and credibility of qualitative analysis. Health Serv. Res. 1999, 34, 1189–1208. [Google Scholar]

- Ernst, M.; Niederer, D.; Werner, A.M.; Czaja, S.J.; Mikton, C.; Ong, A.D.; Rosen, T.; Brähler, E.; Beutel, M.E. Loneliness before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Am. Psychol. 2022, 77, 660–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchini, L.; Centellegher, S.; Pappalardo, L.; Gallotti, R.; Privitera, F.; Lepri, B.; De Nadai, M. Living in a pandemic: Changes in mobility routines, social activity and adherence to COVID-19 protective measures. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 24452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifa, S.A.M.; Swilam, M.M.; El-Wahed, A.A.A.; Du, M.; El-Seedi, H.H.R.; Kai, G.; Masry, S.H.D.; Abdel-Daim, M.M.; Zou, X.; Halabi, M.F.; et al. Beyond the Pandemic: COVID-19 Pandemic Changed the Face of Life. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roben, C.K.P.; Kipp, E.; Schein, S.S.; Costello, A.H.; Dozier, M. Transitioning to telehealth due to COVID-19: Maintaining model fidelity in a home visiting program for parents of vulnerable infants. Infant Ment. Health J. 2022, 43, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naylor, M.; Hirschman, K.; Morgan, B.; McHugh, M.; Shaid, E.; McCauley, K.; Whitehouse, C.; Pauly, M. Challenges and Strategies to Maintain Fidelity to the MIRROR-TCM Intervention During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Innov. Aging 2021, 5, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durosini, I.; Triberti, S.; Sebri, V.; Giudice, A.V.; Guiddi, P.; Pravettoni, G. Psychological Benefits of a Sport-Based Program for Female Cancer Survivors: The Role of Social Connections. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 751077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robbins-Welty, G.A.; Mueser, L.; Mitchell, C.; Pope, N.; Arnold, R.; Park, S.; White, D.; Smith, K.J.; Reynolds, C.; Rosenzweig, M.; et al. Interventionist training and intervention fidelity monitoring and maintenance for CONNECT, a nurse-led primary palliative care in oncology trial. Contemp. Clin. Trials Commun. 2018, 10, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piamjariyakul, U.; Smothers, A.; Young, S.; Morrissey, E.; Petitte, T.; Wen, S.; Zulfikar, R.; Sangani, R.; Shafique, S.; Smith, C.E.; et al. Verifying intervention fidelity procedures for a palliative home care intervention with pilot study results. Res. Nurs. Health 2021, 44, 854–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyons, K.D.; Erickson, K.S.; Hegel, M.T. Problem-solving strategies of women undergoing chemotherapy for breast cancer. Can. J. Occup. Ther. 2012, 79, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyons, K.D.; Newman, R.; Adachi-Mejia, A.M.; Whipple, J.; Hegel, M.T. Content Analysis of a Participant-Directed Intervention to Optimize Activity Engagement of Older Adult Cancer Survivors. OTJR Occup. Particip. Health 2018, 38, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.V.; Friedenreich, C.M.; Moore, S.C.; Hayes, S.C.; Silver, J.K.; Campbell, K.L.; Winters-Stone, K.; Gerber, L.H.; George, S.M.; Fulton, J.E.; et al. American College of Sports Medicine Roundtable Report on Physical Activity, Sedentary Behavior, and Cancer Prevention and Control. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2019, 51, 2391–2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannioto, R.A.; Hutson, A.; Dighe, S.; McCann, W.; McCann, S.E.; Zirpoli, G.R.; Barlow, W.; Kelly, K.M.; DeNysschen, C.A.; Hershman, D.L.; et al. Physical Activity Before, During, and After Chemotherapy for High-Risk Breast Cancer: Relationships With Survival. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2021, 113, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littman, A.J.; Tang, M.T.; Rossing, M.A. Longitudinal study of recreational physical activity in breast cancer survivors. J. Cancer Surviv. 2010, 4, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knell, G.; Robertson, M.C.; Dooley, E.E.; Burford, K.; Mendez, K.S. Health Behavior Changes During COVID-19 Pandemic and Subsequent “Stay-at-Home” Orders. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acito, M.; Rondini, T.; Gargano, G.; Moretti, M.; Villarini, M.; Villarini, A. How the COVID-19 pandemic has affected eating habits and physical activity in breast cancer survivors: The DianaWeb study. J. Cancer Surviv. 2023, 17, 974–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Sullivan, R.; Burns, A.; Leavey, G.; Leroi, I.; Burholt, V.; Lubben, J.; Holt-Lunstad, J.; Victor, C.; Lawlor, B.; Vilar-Compte, M.; et al. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Loneliness and Social Isolation: A Multi-Country Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martell, C.R.; Dimidjian, S.; Herman-Dunn, R. Behavioral Activation for Depression: A Clinician’s Guide, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions, and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions, or products referred to in the content. |

| All Items | BA/PS (n = 58) | Attention Control (n = 55) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | Mean (SD; Range) | n (%) | Mean (SD; Range) | p | |

| Items pertaining only to session 1 | n = 5 | n = 2 | |||

| Review study purpose | 5 (100) | 2 (100) | -- | ||

| Review session structure | 5 (100) | 2 (100) | -- | ||

| Problem-solving attitude | 5 (100) | N/A | -- | ||

| Activity review/COPM | 5 (100) | N/A | -- | ||

| Review structure and rationale for BA/PS | 5 (100) | N/A | -- | ||

| Items for all sessions | n = 58 | n = 55 | |||

| Global rating | 4.6 (0.6; 2–5) | 4.9 (0.3; 4–5) | 0.004 | ||

| Set agenda | 19 (28) | 27 (51) | 0.02 | ||

| Review results of action plan from previous week | 4.7 (0.6; 3–5) | N/A | -- | ||

| Rated satisfaction with effort and outcome and reviewed BA/PS rationale | 3.8 (1.1; 0–5) | N/A | -- | ||

| Defined new activity challenge | 4.9 (0.5; 2–5) | N/A | -- | ||

| Established realistic goal | 4.7 (0.8; 0–5) | N/A | -- | ||

| Generated alternative solutions | 4.6 (0.9; 3–5) | N/A | -- | ||

| Implemented decision-making guidelines and choosing the solutions (pros and cons) | 3.2 (1.1; 2–5) | N/A | -- | ||

| Created action plan | 4.9 (0.8; 0–5) | N/A | -- | ||

| Process (teaching tasks) | 3.5 (1.0; 2.5) | N/A | -- | ||

| Communication and interpersonal effectiveness | 5.0 (0.3; 3–5) | N/A | -- | ||

| Reviews education and recommendations | 5.0 (0; 0) a | 4.9 (0.7; 0–5) | 0.45 | ||

| Asks how education is relevant to participant’s life | 4.6 (1.3; 1–5) a | 4.8 (1.0; 0–5) | 0.58 | ||

| Refer to MD or specialist if wanted | 5.0 (0; 0) b | 5.0 (0; 0) c | -- | ||

| Reviewed previous week activities | N/A | 45 (90) | -- | ||

Avoids components of BA/PS:

| N/A | 5.0 (0; 0) | -- | ||

| N/A | 5.0 (0; 0) | -- | ||

| N/A | 5.0 (0.2; 4–5) | -- |

| Total (n = 250) | BA/PS intervention (n = 123) | Attention control (n = 127) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | |

| Perceived Benefit Questionnaire (PBQ) | ||||||

| Gain Confidence | ||||||

| 0—Not at all | 12 | 4.8 | 3 | 2.4 | 9 | 7.1 |

| 1—Some | 97 | 38.8 | 47 | 38.2 | 50 | 39.4 |

| 2—A great Deal | 141 | 56.4 | 73 | 59.3 | 68 | 53.4 |

| Reduce Distress | ||||||

| 0—Not at all | 24 | 9.6 | 10 | 8.1 | 14 | 11 |

| 1—Some | 110 | 44 | 53 | 43.1 | 57 | 44.9 |

| 2—A great Deal | 116 | 46.4 | 60 | 48.8 | 56 | 44.1 |

| Set Goals | ||||||

| 0—Not at all | 17 | 6.8 | 3 | 2.4 | 14 | 11 |

| 1—Some | 85 | 34 | 26 | 21.1 | 59 | 46.5 |

| 2—A great Deal | 148 | 59.2 | 94 | 76.4 | 54 | 42.5 |

| Adjust Habits and Routines | ||||||

| 0—Not at all | 22 | 8.8 | 8 | 6.5 | 14 | 11 |

| 1—Some | 106 | 42.4 | 43 | 35 | 63 | 49.6 |

| 2—A great Deal | 122 | 48.8 | 72 | 58.5 | 50 | 39.4 |

| Increase Exercise | ||||||

| 0—Not at all | 33 | 13.2 | 9 | 7.3 | 24 | 18.9 |

| 1—Some | 117 | 46.8 | 48 | 39 | 69 | 54.3 |

| 2—A great Deal | 100 | 40 | 66 | 53.7 | 34 | 26.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stevens, C.J.; Wechsler, S.; Ejem, D.B.; Khalidi, S.; Coffee-Dunning, J.; Morency, J.L.; Thorp, K.E.; Codini, M.E.; Newman, R.M.; Echols, J.; et al. A Process Evaluation of Intervention Delivery for a Cancer Survivorship Rehabilitation Clinical Trial Conducted during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Curr. Oncol. 2023, 30, 9141-9155. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30100660

Stevens CJ, Wechsler S, Ejem DB, Khalidi S, Coffee-Dunning J, Morency JL, Thorp KE, Codini ME, Newman RM, Echols J, et al. A Process Evaluation of Intervention Delivery for a Cancer Survivorship Rehabilitation Clinical Trial Conducted during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Current Oncology. 2023; 30(10):9141-9155. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30100660

Chicago/Turabian StyleStevens, Courtney J., Stephen Wechsler, Deborah B. Ejem, Sarah Khalidi, Jazmine Coffee-Dunning, Jamme L. Morency, Karen E. Thorp, Megan E. Codini, Robin M. Newman, Jennifer Echols, and et al. 2023. "A Process Evaluation of Intervention Delivery for a Cancer Survivorship Rehabilitation Clinical Trial Conducted during the COVID-19 Pandemic" Current Oncology 30, no. 10: 9141-9155. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30100660

APA StyleStevens, C. J., Wechsler, S., Ejem, D. B., Khalidi, S., Coffee-Dunning, J., Morency, J. L., Thorp, K. E., Codini, M. E., Newman, R. M., Echols, J., Cloyd, D. Z., dos Anjos, S., Muse, C., Gallups, S., Goedeken, S. C., Flannery, K., Bakitas, M. A., Hegel, M. T., & Lyons, K. D. (2023). A Process Evaluation of Intervention Delivery for a Cancer Survivorship Rehabilitation Clinical Trial Conducted during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Current Oncology, 30(10), 9141-9155. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30100660