1. Introduction

Cancer, a multifaceted illness, emerges and progresses under the influence of not only genetic and environmental factors but also intricate psychological and emotional elements [

1]. A major consequence of these intersecting influences is an impact on the immune system, making the patient’s emotional and psychological well-being crucial to the disease’s prognosis. As patients undergo treatment for cancer, a myriad of physical, cognitive, and social alterations become evident [

2,

3]. These changes range from decreased social functioning and the onset of physical and cognitive disorders to heightened somatic complaints [

4,

5]. Furthermore, concerns about treatment efficacy and the looming threat of cancer recurrence exacerbate the emotional distress experienced by these patients [

1,

4,

5,

6].

While there is a significant volume of research dedicated to psychiatric disorders and the quality of life in cancer patients, studies concerning the emotional processes related to their mental states and potential interventions to bolster emotional strength remain relatively scarce [

7]. Recent studies have begun to spotlight self-compassion and stress as pivotal factors that substantially influence the disease’s trajectory [

8]. Self-compassion, as conceptualized, represents an emotional regulation mechanism, whereby individuals acknowledge and accept their vulnerabilities, exhibiting kindness, tolerance, and understanding towards themselves [

9]. Recognizing suffering as an inherent part of the human experience, individuals must extend care and compassion to themselves amidst their imperfections.

In the realm of psycho-oncology, understanding the multifaceted psychological dimensions of cancer patients has gained paramount importance. While resilience, defined as the ability to “bounce back” and adapt amidst adversity, emerges as a pivotal construct [

10], cognitive emotional regulation strategies—how individuals consciously manage and respond to emotionally laden situations—play an equally indispensable role. These strategies can range from re-appraisal and acceptance to suppression, guiding patients in processing and grappling with the intricate nuances of their diagnosis and treatment journey [

11].

Alongside these constructs, alexithymia warrants meticulous attention. The term, rooted in the Greek words “a” (none), “lexis” (word), and “thymos” (emotion), epitomizes the difficulty some individuals face in finding words to articulate their emotions [

12]. Notably not enlisted in diagnostic manuals such as ICD-10 or DSM-4, alexithymia nevertheless signifies a pervasive psychosomatic phenomenon characterized by impediments in identifying, distinguishing, and conveying emotions. Individuals with alexithymia may be unaware of their emotional states, tending to express their feelings through somatic complaints [

13]. Alexithymia has been linked to a variety of psychopathological symptoms including depression, anxiety, somatization, hostility, and paranoia, and can foster a heightened susceptibility to mental disorders, diminish the efficacy of psychotherapy, and negatively influence the development and severity of psychopathological symptoms. Alarmingly, it is reported in approximately 10% of the general populace [

14]. A study focusing on cancer patients discovered that over half of the participants exhibited alexithymia, a condition strongly correlated with a more severe perception of the negative outcomes and feelings associated with their illness [

15].

Collectively, these elements—resilience, cognitive emotional regulation, and alexithymia—paint a comprehensive portrait of the adaptive and maladaptive psychological tools that could potentially influence the emotional and mental well-being of cancer patients [

10,

11,

13,

15].

Understanding the intricate interplay between self-compassion, cognitive emotion regulation, alexithymia, emotional resilience, depression, and anxiety is crucial for safeguarding the psychosocial well-being of cancer patients. In this study, our primary objective was to assess these psychological constructs in cancer patients. Furthermore, we sought to discern the relationships and potential interdependencies among self-compassion, cognitive emotion regulation, alexithymia, emotional resilience, depression, and anxiety. A key focus of our investigation was to determine if emotional resilience and cognitive emotion regulation function as mediators between self-compassion and both depression and anxiety symptoms.

3. Results

A total of 151 cancer patients were evaluated in the study. The average age of the patients was 54.94 ± 12.65 years. Descriptive characteristics of the study population are presented in

Table 1.

The 151 stage 4 cancer patients exhibited various psychological attributes and states as assessed through an array of standardized scales. On the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), the participants scored 15.38 ± 4.17 and 11.83 ± 3.00, respectively. Detailed examination through the Self-Compassion Scale (SCS) revealed the following scores across its subscales: self-kindness (2.08 ± 0.59), self-judgment (3.20 ± 0.92), common humanity (2.09 ± 0.41), isolation (2.73 ± 0.76), mindfulness (1.96 ± 0.62), and over-identification (3.54 ± 1.07), culminating in a total SCS score of 14.67 (±2.24) (

Table 2).

Exploring the cognitive emotion regulation strategies using the Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (CERQ) offered the following scores: self-blame (12.59 ± 4.29), acceptance (8.57 ± 2.32), rumination (14.63 ± 4.19), positive refocusing (7.77 ± 1.83), refocus on planning (9.29 ± 2.59), positive reappraisal (9.36 ± 3.21), putting into perspective (8.86 ± 3.12), catastrophizing (10.72 ± 3.43), and other blame (9.79 ± 2.95). This translated to an adaptive CERQ score of 43.86 ± 6.67 and a maladaptive CERQ score of 47.73 ± 8.69.

Further, the Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS) noted scores of 17.29 ± 5.32 for difficulty in describing feelings (DDF), 17.01 ± 5.79 for difficulty in identifying feelings (DIF), and 19.92 ± 3.23 for externally oriented thinking (EOT). Lastly, the participants exhibited a resilience score of 2.11 ± 0.39 as measured through the Brief Resilience Scale (BRS), and perceived pain scored at 6.37 ± 2.30 on the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS).

The Pearson correlation analysis showed that BDI is notably negatively correlated with SCS (r = −0.430,

p < 0.01) and adaptive CERQ (r = −0.399,

p < 0.01), but positively correlated with maladaptive CERQ (r = 0.399,

p < 0.01). Additionally, SCS demonstrated strong negative associations with the sub-scale “overidentification” (r = −0.666,

p < 0.01) and “self-judgement” (r = −0.571,

p < 0.01). Other scales and subscales present various levels of significance, with detailed coefficients and significance levels provided in

Table 3.

To analyze the factors influencing depression, multiple regression analysis was conducted with BDI as the dependent variable, while SCS, adaptive and maladaptive CERQ, DDT DIF, EOT, BRS, and VAS scores served as independent variables. This model, leveraging SCS, both adaptive and maladaptive CERQ, BRS, and VAS as independent variables, accounts for 39% of the variability in BDI scores (F (8142) = 11.539,

p < 0.001). Within this array of variables, both maladaptive CERQ and VAS exhibited a positive predictive impact on BDI, while SCS, adaptive CERQ, and BRS had a negative predictive influence (

Table 4).

To facilitate the understanding of the tables presented, it is pertinent to elucidate the interpretation of the unstandardized B coefficients depicted. These coefficients signify the magnitude of change to be expected in the dependent variable, which in this context is the BDI scores, correlating with a one-unit alteration in the independent variables while maintaining the other variables at a constant value. Taking an exemplar from the univariate regression analysis, the B value attributed to the SCS stands at −0.798. This indicates that with every unitary increase in the SCS score, there is an anticipated decrease of 0.798 units in the BDI score, under the assumption that all other variables in the equation are held constant. This understanding is vital in decoding the intricate relationships between the different psychological metrics and their combined influence on the BDI scores.

To determine the predictors of anxiety, a multiple regression analysis was executed with BAI designated as the dependent variable and SCS and BRS as the independent variables. This configuration, utilizing SCS and BRS as independent elements, justifies 10% of the variation in BAI scores, according to the equation F (2148) = 8.175,

p < 0.001. The analysis revealed that both SCS and BRS bear a negative predictive relationship with BAI, as detailed in

Table 5.

To scrutinize the intermediary role of emotional resilience in connecting self-compassion and depression, a mediational examination was undertaken. The mediation model encompassed calculations of both direct and indirect impacts. As depicted in

Figure 1, a notable direct influence of self-compassion on depression was discerned (b = −0.482, CI = −0.750 to −0.214,

p = 0.001), indicating that enhanced self-compassion correlates with diminished depression scores.

Moreover, substantial indirect associations were established both between self-compassion and depression mediated by resilience and between self-compassion and depression mediated by cognitive emotion regulation. These relations emphasize the critical roles that emotional resilience and cognitive emotion regulation strategies undertake in bridging self-compassion and depression, a connection corroborated as statistically substantial in

Table 6.

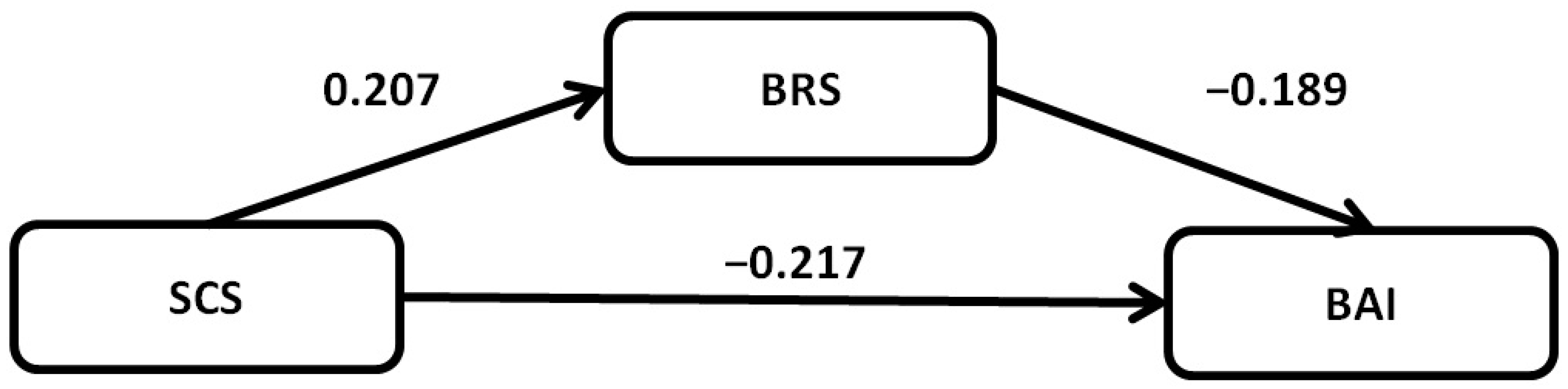

Further mediational analysis was carried out to evaluate the intermediary function of emotional resilience in aligning self-compassion and anxiety, with the findings articulated in

Table 7. The analysis unearthed significant pathways both direct and indirect, with emotional resilience showcasing a considerable mediating role in this nexus. The partial indirect mediational influence of emotional resilience in the tie between self-compassion and anxiety was established to be statistically noteworthy (

Figure 2).

4. Discussion

Our study represents a pivotal exploration into the mediating effects of resilience and cognitive emotion regulation strategies on the influence of self-compassion (SC) as a determinant of reduced depression levels in patients diagnosed with a malignancy. Our findings robustly emphasize the significant contribution of SC in mitigating depression severity, reinforcing its validity as a primary predictor in our analysis. Consistent with our hypotheses, self-compassion, resilience, and cognitive emotion regulation strategies emerged as protective bulwarks against depression. Specifically, individuals with cancer diagnoses who exhibited diminished self-compassion, resilience, and adaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies presented with heightened depression scores. Of note, resilience and cognitive emotion regulation strategies not only demonstrated their own merits as protective factors but also acted as vital mediators in the relationship between SC and depression, as measured by the BDI. Beyond the role of SC, the mediating influences of resilience and cognitive emotion regulation strategies suggest their value as key targets in therapeutic interventions aimed at reducing depression. Furthermore, our findings bolster the case for the integration of compassion-focused interventions in mental health care, especially for those facing profound stressors, such as patients grappling with cancer. Given the marked impact of self-compassion on depression, there’s a compelling argument for embedding compassion-centric modules within therapeutic frameworks to augment their efficacy.

In our examination of cancer types, consistent with the broader literature, breast and lung cancers emerged as the most prevalent [

24,

25]. The study delved into the psychological turmoil often encountered by individuals grappling with a cancer diagnosis, a scenario that potentially escalates the symptoms of anxiety and depression. This pattern aligns with prior research that showcases the notable emotional turmoil in this group, a consequence of the intricate dynamics associated with the treatment trajectory, persistent fears of relapse, and the existential dilemmas spurred by the affliction [

26,

27].

The insights gained from the Self-Compassion Scale (SCS) were illuminating. Individuals diagnosed with cancer exhibited diminished scores on SCS subscales, including self-kindness, common humanity, and mindfulness. In contrast, they recorded elevated scores in negative domains like self-judgment, isolation, and over-identification. This deviation accentuates the deleterious psychological sequelae of the illness, where patients might harbor feelings of isolation, augmented self-criticism, and a reduced capacity to remain grounded in the present [

28]. Prior studies have emphasized the therapeutic potential of self-compassion in alleviating distress, underscoring its importance in cancer care [

29].

Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (CERQ), another focal point of the study, showed that cancer patients were more prone to self-blame, rumination, and catastrophizing, while demonstrating lower scores in adaptive strategies like positive refocusing and positive reappraisal. The inclination to catastrophize, coupled with tendencies for self-blame, can augment feelings of despair and powerlessness, further eroding their psychological well-being [

11,

30,

31,

32].

Alexithymic traits were investigated among the cancer patients in the study, as evidenced by the scores from the Difficulty in Identifying Feelings (DIF) and Difficulty in Describing Feelings (DDF) components of the Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS). These scores indicate potential challenges in recognizing and expressing emotions, which could obstruct effective emotional processing and hinder adaptive coping mechanisms. This is in line with the observations made in the study by Lumley et al., which identified similar challenges in emotional processing [

33]. Further research by Yeung et al. underscored the role of alexithymic characteristics such as these in influencing functional well-being, particularly noting the barriers created in emotional processing due to difficulties in identifying and describing feelings [

13]. In light of the observed alexithymic traits, implementing emotion-focused therapies might also prove fruitful. By assisting patients in identifying, labeling, and articulating their emotions, the emotional processing can be facilitated, potentially reducing psychological distress. One such therapeutic approach is the Emotion Regulation Group Therapy, which has shown promise in helping individuals with emotion regulation difficulties [

34].

In the context of resilience, it transcends mere endurance; it is a repository of protective attributes and personal strengths that facilitate successful adaptation, encompassing elements such as optimism, strong coping mechanisms, and robust social support systems. It is noteworthy that resilience is a dynamic attribute, potentially fluctuating due to a variety of factors including evolving life circumstances and situational challenges. Remarkably, many cancer patients successfully traverse the stressful path of their illness, managing to maintain a semblance of normality in their daily routines and in some instances, experiencing personal growth. It is noteworthy that the journey through cancer can markedly erode this resilience, reflected in the BRS scores of the patients in our study. This erosion of resilience amidst the hardships of the disease accentuates the intricate interplay of physical and psychological challenges they undergo. Not just a testament to the adversities they face, it puts a spotlight on a critical area for support and intervention to enhance their coping mechanisms and improve their quality of life during their cancer journey [

10].

A salient aspect of our investigation revolved around the subjective experiences of pain among cancer patients. Pain, both acute and chronic, is frequently intertwined with cancer diagnoses and treatment regimens [

35]. Our findings indicated a significant correlation between the intensity of pain and emotional distress markers. Notably, participants reporting higher pain levels often exhibited lower self-compassion scores and relied more heavily on maladaptive cognitive emotional regulation strategies. This suggests that the physical distress of pain may exacerbate emotional turmoil, further underscoring the need for comprehensive pain management in tandem with psychological interventions. It is also crucial to consider the potential bidirectional nature of this relationship, as while pain might heighten emotional distress, maladaptive emotional coping might, in turn, intensify the perception of pain. This intricate relationship calls for a holistic approach to patient care, where pain management and psychological well-being are treated as interconnected domains.

While the study delineates the psychological profile of cancer patients, it also ventures into an unexplored avenue—the potential differences in psychological distress based on the type of malignancy. We observed a distinct variation in BDI scores across various cancer types, with pancreatic cancer patients presenting the most elevated scores, which indicate a higher level of depressive symptoms in this subgroup. This finding prompts a deeper investigation into the underpinnings of these high scores, possibly opening doors to a nuanced understanding of the psychological landscape of cancer patients. It can encourage future research to move towards a more individualized approach to psychological assessment and intervention, allowing for strategies that address not only the general distress experienced by cancer patients but also the specific distress patterns associated with different types of cancer. Recognizing the unique challenges faced by pancreatic cancer patients, in particular, might pave the way for targeted interventions to improve their psychological well-being [

36].

Mediational analyses provided crucial insights into the complex relationships among self-compassion, resilience, cognitive emotion regulation, depression, and anxiety. The research affirms the mediating of emotional resilience in navigating the connections between self-compassion and the manifestations of both depression and anxiety. This buttresses the assertion that resilience and self-compassion are intertwined constructs, where fostering self-compassion can bolster resilience, thus ameliorating the mental health outcomes for cancer patients [

37].

The pronounced negative coefficient (b = −0.482) in the direct link between self-compassion and depression stands as a significant finding. It indicates a tendency for individuals harboring higher self-compassion to report diminished depression scores, a trait possibly fostered by a gentler self-view and decreased self-reproach, aligning with earlier research narratives. A possible explanation for this could be the core components of self-compassion, which include self-kindness, a sense of shared humanity, and mindfulness [

9]. These components enable individuals to treat themselves with kindness, understand their struggles as part of the broader human experience, and observe their feelings non-judgmentally. Collectively, these elements could counteract the feelings of isolation, rumination, and self-criticism that often accompany depression.

Similarly, cognitive emotion regulation strategies, which encompass how individuals think about their emotions and how they handle them, can be influenced by self-compassion. A self-compassionate mindset might deter maladaptive cognitive strategies, such as rumination or catastrophizing, which are often implicated in depressive symptomology. Instead, individuals might be encouraged to adopt more adaptive strategies, like positive reappraisal or acceptance. Fostering a self-compassionate approach could potentially curb the reliance on maladaptive cognitive processes like rumination or catastrophizing, frequently associated with depressive symptoms. Conversely, it might promote the adoption of adaptive strategies such as positive reappraisal or acceptance, steering individuals toward a healthier mental state.

The mediational model for anxiety mirrored that of depression, further solidifying the protective role of self-compassion. The indirect effects point to emotional resilience as a potential buffer against anxiety, positing that self-compassionate individuals may develop stronger emotional coping mechanisms that reduce anxiety susceptibility.

While scant research has probed into the interplay of self-compassion, resilience, and cognitive emotion regulation within the cancer patient demographic, these concepts resonate deeply in broader populations. Neff’s depiction of self-compassion positions it as a robust shield against depression and anxiety, corroborated by studies like that of Van Dam et al. [

9,

38]. The literature distinctly underscores the tandem effect of mindfulness and self-compassion in assuaging emotional distress, propelling resilience to the forefront as a potential mediating agent [

39]. Resilience, framed as the innate human capacity to rebound from setbacks, melds seamlessly with mindfulness, and stands as a cornerstone in well-being outcomes [

40]. Preliminary links suggest a deep-rooted symbiosis between resilience and self-compassion, although further exploration remains due [

41].

Reflecting upon the extant literature and the revelations from our investigation, it is evident that self-compassion, whether directly or mediated via resilience, cast a profound impact on emotional states like anxiety and depression. Remarkably, consistent with earlier anticipations, our analysis amplifies the unique potency of self-compassion, suggesting it might even overshadow mindfulness in orchestrating emotional equilibrium. Such insights accentuate the imperativeness of weaving mindfulness, self-compassion, and resilience into therapeutic paradigms, fostering a comprehensive upliftment in patient wellness trajectories.

4.1. Clinical Implications

The rising global incidence of cancer, coupled with increased mortality rates for certain malignancies, underscores the persistent challenges faced by the community in the comprehensive management of cancer. Against this backdrop, the findings from our study take on heightened importance, offering pivotal clinical insights, particularly in the field of oncological therapy [

42]. The intricate relationship between self-compassion, emotional resilience, and cognitive emotional regulation strategies offers a roadmap for clinicians to structure targeted interventions. In particular, the elevated prevalence of maladaptive emotion regulation strategies among cancer patients suggests an immediate need for interventions that prioritize cognitive restructuring and emotion-focused coping. Clinicians might consider incorporating modules on enhancing self-awareness and emotional recognition, given the challenges associated with alexithymia. Furthermore, the evident benefits of self-compassion as a buffer against emotional distress underline its potential as a therapeutic tool. Healthcare practitioners may also need to take into account the heterogeneity of cancer experiences; individualized interventions that cater to the specific emotional needs and profiles of patients may prove more efficacious than one-size-fits-all approaches. Given the significant mediational roles of emotional resilience and cognitive emotion regulation, interventions that bolster these components could be especially beneficial for individuals prone to depression and anxiety. For instance, resilience training programs or cognitive behavioral therapy, which focus on building resilience and refining cognitive emotion regulation strategies, respectively, could be particularly effective. These interventions, combined with practices that nurture self-compassion, like mindfulness-based stress reduction or compassion-focused therapy, could offer a multifaceted approach to mental well-being. By offering techniques to cope with adversity and maintain emotional equilibrium, these programs can serve as a crucial pillar of support for cancer patients.

While the current study provides essential insights into the psychological landscape of cancer patients, several avenues remain to be explored. Longitudinal studies can shed light on the evolving psychological dynamics over different stages of the cancer journey—from diagnosis to treatment and potential remission or recurrence. Such investigations can chart the ebb and flow of psychological parameters, enabling a more comprehensive understanding. Additionally, exploring potential moderating variables, like social support, types of cancer, and stages of cancer, can offer a more nuanced perspective. The potential protective role of factors like familial support, community involvement, or even spiritual beliefs, in the face of a cancer diagnosis, remains a fertile ground for exploration.

4.2. Limitations

The study, though insightful, bears several potential limitations that warrant consideration. First, its cross-sectional design precludes the establishment of definitive causality, making longitudinal studies a more desirable avenue for verifying directional relationships among self-compassion, emotional resilience, cognitive emotion regulation, depression, and anxiety. The reliance on self-report measures poses the risk of introducing biases, as participants may not consistently offer accurate or forthright responses, potentially influenced by social desirability or an imprecise self-awareness. Moreover, the findings’ applicability may be circumscribed by the sample characteristics, especially if lacking diversity in age, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, or other pertinent demographics. Additionally, the operational definitions and measurements for self-compassion, emotional resilience, and cognitive emotion regulation might not wholly encapsulate the breadth and nuances of these intricate constructs, leaving room for potential oversights or cultural biases. Unexamined confounding variables, such as past traumas, present-day stressors, or support structures, might unduly affect the delineated relationships. Furthermore, while emotional resilience and cognitive emotion regulation are spotlighted as mediators, other latent factors could also play a pivotal role but remain unexplored. External elements like societal or cultural dynamics, which might interplay with the central variables, may not be adequately considered. Without tangible experimental data, extrapolating actionable therapeutic interventions from merely observed correlations remains a challenge.