Abstract

Background: In the past century, the importance of historical villages has been highly recognized, as they serve aesthetic, functional, and environmental values and can foster local socioeconomic development through the heritagization process. The purpose of this paper is to outline the core features of the preservation and management of historical villages in the European and Chinese contexts. Methods: Using a qualitative systematic literature review, the research was based on international academic papers covering 73 case studies from the two contexts, addressing the fact that little work has been carried out comparing European and Chinese realities. Results: Similarities and differences in rural cultural heritage preservation and management between Europe and China were compared and discussed, paying particular attention to historical villages in both contexts. Using this method, rural heritage preservation in China can be better framed and analyzed for scholars engaged in both the Chinese and international contexts. Conclusions: Inspired by the European case studies, the research suggests that capacity building of different types of stakeholders, contextualized financial mechanism and multiple values the civic society perceived and recognized during the Chinese rural heritage preservation and management process should be further studied and implemented case by case based on a historical-sensitive approach. In addition, the issue of the lack of social capital and policy arrangements in rural areas should be further addressed to stimulate community resilience.

1. Introduction

Agricultural development has given birth to the European rural landscape over the course of history, and it still impacts on a variety of traditions and cultures in contemporary Europe [1]. This is evident in particular in Southern Europe where the land has been intensively cultivated around the deltas of Mediterranean basin [2]. China as an agricultural country possesses abundant agricultural resources, is the home to a variety of cultivation methods and diverse rural landscapes [3]. However, in the past few centuries, rural areas in both China and Europe have experienced several processes of transition from productivism to post-productivism and different degrees of degradation. Abundant rural cultural heritage rooted in both contexts are at risk of disappearing. In order to address this situation, the enhancement of rural cultural heritage in discourse and policy framework has commonly emerge in both contexts, despite different approaches which have been taken.

Rural cultural heritage contributes to aesthetic pleasure and quality of life, and it is the carrier of the history of a community [4]. It is one of the constituent elements in local identity and the sense of belonging, based on which the educational and didactic function is also identifiable [5]. The enhancement of such treasure generates visible economic benefits for the quality of life of local people [6]. Therefore, rural heritage preservation is an essential issue that activates local economies and enhances the cultural identity of local communities [7,8]. At international level, in the past century, several influential debates have emphasized the importance of preserving rural cultural heritage, showing that the discourse has shifted from monuments to groups of buildings in towns and villages in their natural and human-made settings [9]. Moreover, rural heritage has begun to be perceived as the result of interactions between people and nature within a certain spatiotemporal context and has been strongly valued in recent preservation practices, as it constitutes an indispensable part of the cultural landscape of a given territory [10]. In China where a set of developmental policies started to benefit rural areas in recent decade, rural heritage preservation has been highlighted as a constituent part of the developmental strategy under the rural revitalization framework at a national level [11].

Historical villages are those villages that reflect the conditions of historical culture and social development, and essential barriers of traditional culture, customs, and architectural arts in various places [12]. Against this background, historical villages are highly valued because their aesthetic, functional, and environmental values can make them venues for socioeconomic development through efficient preservation and management [13,14].

This phenomenon is particularly evident in China, where economic development based on rural heritage preservation and management has been pivotal for local societies and central in political campaigns in recent decades [15,16]. In China, despite a double-tracked system for historical village preservation has been framed, the government-led approach in selecting and transforming villages to be protected has received severe criticism. Some scholars have paid attention to the Chinese approach, in which rural cultural heritage preservation was conceived as a response to the emerging need to revitalize rural areas and alleviate poverty in the Chinese countryside [17,18].

In other cases, in European countries, where the tradition of heritage conservation is strong and social capital is abundant [19,20], preservation practices concerning both physical spaces and the cultural identities of local communities have resulted in a value-oriented and people-centered approach thanks to a rather long-term vision informing the measures and strategies applied [21,22,23]. In Europe, rural heritage preservation has been one of the principal parts of the Local Development Program, which has widely impacted on the policies and practices. Despite rural construction regulations that empower the preservation of rural landscape which have been developed by the EU countries, many historical villages have been facing continuous physical degradation, and the loss of their heritage value. New methodologies for scientific research of heritage studies and a new vision with which the sustainable and resilient development in rural area can be combined with the goal of rural cultural heritage should be developed and discussed.

This systematic review is based on an article retrieval performed with Scopus database on 15 March 2022. The results showed that 10 papers were published on the topic of rural heritage preservation in 2008, and the annual number increased gradually to 23 by 2021. Despite a growing corpus of literature investigating physical and societal changes in rural cultural heritage preservation processes in different geographies and cultural contexts, few studies applied comparative analysis of China and Europe [24]. Moreover, little attention has been paid to rural heritage preservation practices regarding historical villages from a comparative perspective. Some authors in the cultural heritage field have conducted systematic reviews investigating the state of the art of civic participation and heritage management [25], computational methods for heritage conservation [26], and the relationship between cultural heritage and climate change [27]. Therefore, a systematic review method was designed based on internationally published academic papers covering case studies of historical villages in both the European and Chinese contexts, outlining the core features of preservation and management.

This research contributes to the rural cultural heritage preservation literature in the following ways. First, it provides a holistic picture of how historical villages have been changed, and by whom, in the European and Chinese contexts, through a review of 73 case studies. Second, it analyzes differences between and common features of the preservation of historical villages in Europe and China. Third, in contrast to the European experience, the authors pay particular attention to the Chinese approach, which has been characterized by an “authorized heritage discourse” [28], suggesting that capacity building of the stakeholders involved, appropriate financial mechanism and multiple values the civic society perceived and recognized during the rural heritage preservation and management process should be further addressed. The issue of the lack of social capital and policy arrangements in rural areas should be appropriately adjusted in the Chinese context. In addition, a historical-sensitive approach and policy arrangements in Chinese rural areas require further adjustment.

The literature review comprises two parts. The first part consists of a systematic review and analysis of recurrent studies on topics of rural cultural heritage preservation and development in the European and Chinese contexts. The selection and collection of articles was based on several criteria (see Section 2.1). Regarding articles and cases from Europe and China, the review draws on qualitative approaches based on 50 selected papers and 73 case study villages in the international academic literature (see Supplementary Tables S1 and S2). The selected works comprise 24 manuscripts describing 28 European cases and 26 describing 45 Chinese cases. This review is an attempt to trace an outline of the key issues from the European and Chinese perspectives, paying attention to how, and by whom, historical villages have been preserved and/or transformed.

The second part of the literature review identifies a set of key themes, based on which a qualitative review was developed (see Section 3 and Section 4). This part of the review focused on checking whether each case study village had experienced physical changes as a result of labeling, spatial planning, project-making, demolition and relocation, commodification, or funding. Furthermore, an investigation into the stakeholders involved and the performance of public participation was also carried out. The data from the systematic review were collected and are listed in two tables as supplementary data.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Publication Selection

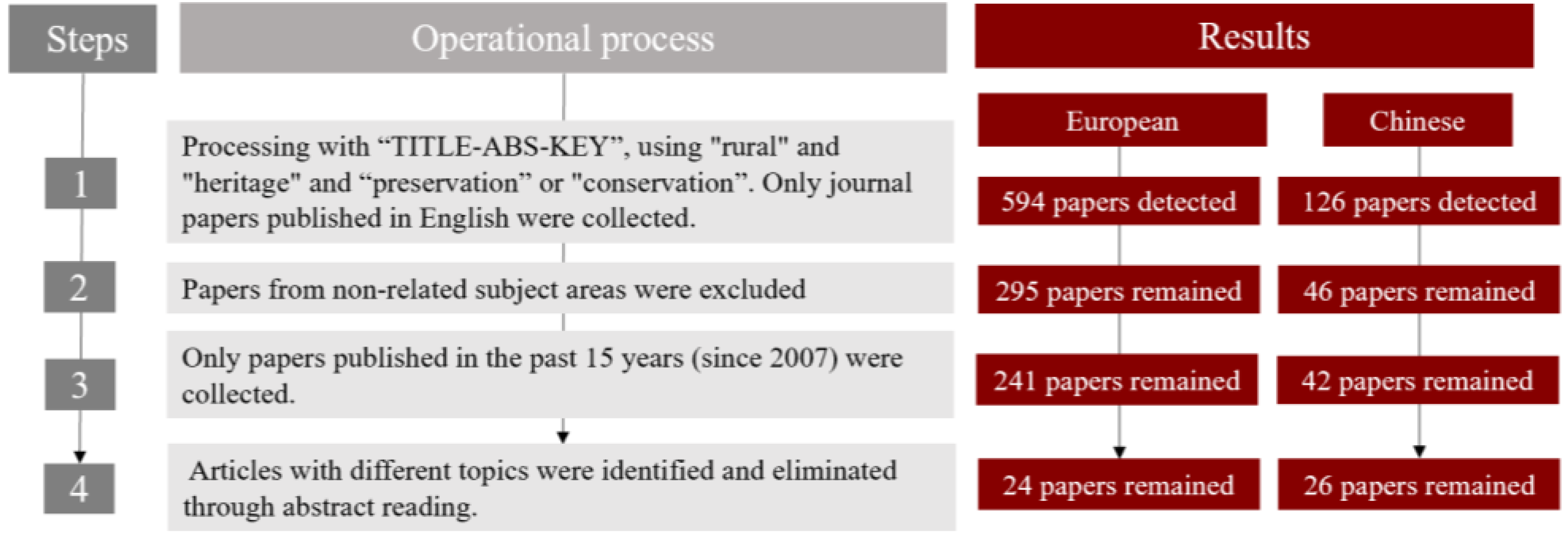

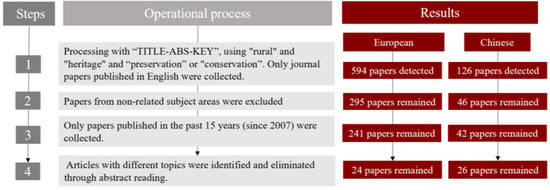

The systematic review was developed through a process of literature retrieval, applying search strings in the Scopus database on 15 March 2022. This method was selected because it provides wider coverage of publications, citations, and document types [29]. The selection process followed a method previously tested by Li et al. (2020) and Barrientos et al. (2021). The paper collection process that the authors used is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of operational process for paper selection. Authors’ elaboration.

The first author began the retrieval process with a “TITLE-ABS-KEY” search using “rural” and “heritage”, plus “preservation” and/or “conservation” as keywords. The process included a set of criteria applied for each paper: year of publication, keywords, relevance of the topic, language, and accessibility. The selection was limited to papers published in English-language journals. In the first stage, 594 papers were collected. In addition, articles from unrelated areas were identified by reading abstracts and were eliminated, after which 295 papers remained. It was found that there was a gradual increase in the number of international academic publications on rural heritage preservation in around 2008 (6 papers on related topics were published in 2007, and the number reached 11 in 2008), while by 2021, the number had increased to 28. Thus, we included articles published in the last 15 years, and 241 papers remained after this stage. We then read the selected papers from international cases in detail to obtain those from the European context. After the four rounds of retrieval, 24 articles including 28 case studies related to the European context were kept. The same procedure was performed for Chinese case studies. The papers detected at the first three stages were 126, 46 and 42, accordingly. At the end, 26 papers focusing on 45 case studies regarding Chinese rural heritage preservation were analyzed. A further 50 articles related to Chinese rural revitalization, rural governance, and cultural tourism were collected and reviewed to support better contextualization. The process has been supervised by the second author, independently. The basic characteristics of all selected papers and related cases were identified, and are reported in two supplementary tables.

2.2. Focus Themes

To understand each publication’s outcomes, 50 papers including 73 case studies from the European and Chinese context were categorized according to their themes and keywords. Apart from the basic information each case study village contain (including the name of case study village, its geographical location, and the country), the focus themes cover mainly four aspects as follows:

(1) Heritage preservation/conservation processes: This aspect included whether the case study village was labeled, impacted by planning activities and intentional advertisement. By labeling certain types of historic remains as cultural heritage, it can raise awareness and help to share values and principles regarding heritage preservation and promotion [30]. Nominating certain things as heritage and then commodifying them as tourist resources is common in rural areas worldwide [19,31]. In this process, planning and project-making often play key roles in addressing preservation and development activities that can be perceived as part of a rational process of coordinating and systemizing different resources into a holistic management plan. Planning activities around heritage preservation should include the following steps: (i) a research phase, in which the main task is to clarify the community’s goals; (ii) a phase to elaborate the plan; (iii) a phase to implement the plan; and (iv) a phase for review and revision [32]. At the international level, some common elements of successful and coherent heritage planning approaches are provided by Article 111 of the UNESCO Operational Guidelines (2021) [33], in which the recommended steps include having a shared understanding of the property, facilitating a participatory planning and stakeholder consultation process, building capacity, and providing an accountable, transparent description of how the system functions, in order to build an effective management system [6]. Therefore, it is important to investigate if the preservation and development processes were characterized by plans, project-making, demolition, and relocation.

(2) Rural tourism development and management: This aspect was often related to the commodification process.

(3) Funding issues: It was crucial to understand the financial issues presented by each case study.

(4) Stakeholders: The government is a key stakeholder in heritage preservation [34]. Considering the diversity of government systems and political settings that appeared in the selected papers and case studies [35], the state government has devolved to regional and municipal level bodies in European context. And in China, this category refers to provincial, municipal, county, and township governments. Moreover, business of different natures were considered, including private business (P), state-owned enterprises (SOEs), and community-owned enterprises; the latter refers to businesses run communally by villages [36]. Furthermore, the role of experts was considered, as they play an important leadership role and had an impact on the preservation and development of the case study villages [37]. For the case studies in the Chinese context, it was found that leaders of historical villages are important interlocutors in rural traditional societies where local elites and village cadres have an influential presence [16,38]. Village committees and the constituent members (village cadres), as the lowest level of institutional organization, have a relevant role in this context due to administrative decentralization and the tax-sharing reform in the 1990s [39], as they intervene in project implementation within the top-down spatial setting of macro policies [40]. Therefore, compared to the European cases, village leaders in China represented another type of stakeholder, as mentioned in point 5 above. Different NGOs and public participation in communities were considered as well. In conclusion, the stakeholders involved are crucial, as the different patterns they shape can further contribute to the features of heritage practices (government-led, community based, or hybrid) [41] and influence public participation in the long-term sustainability of local societies.

3. Results

3.1. An Overall Comparison

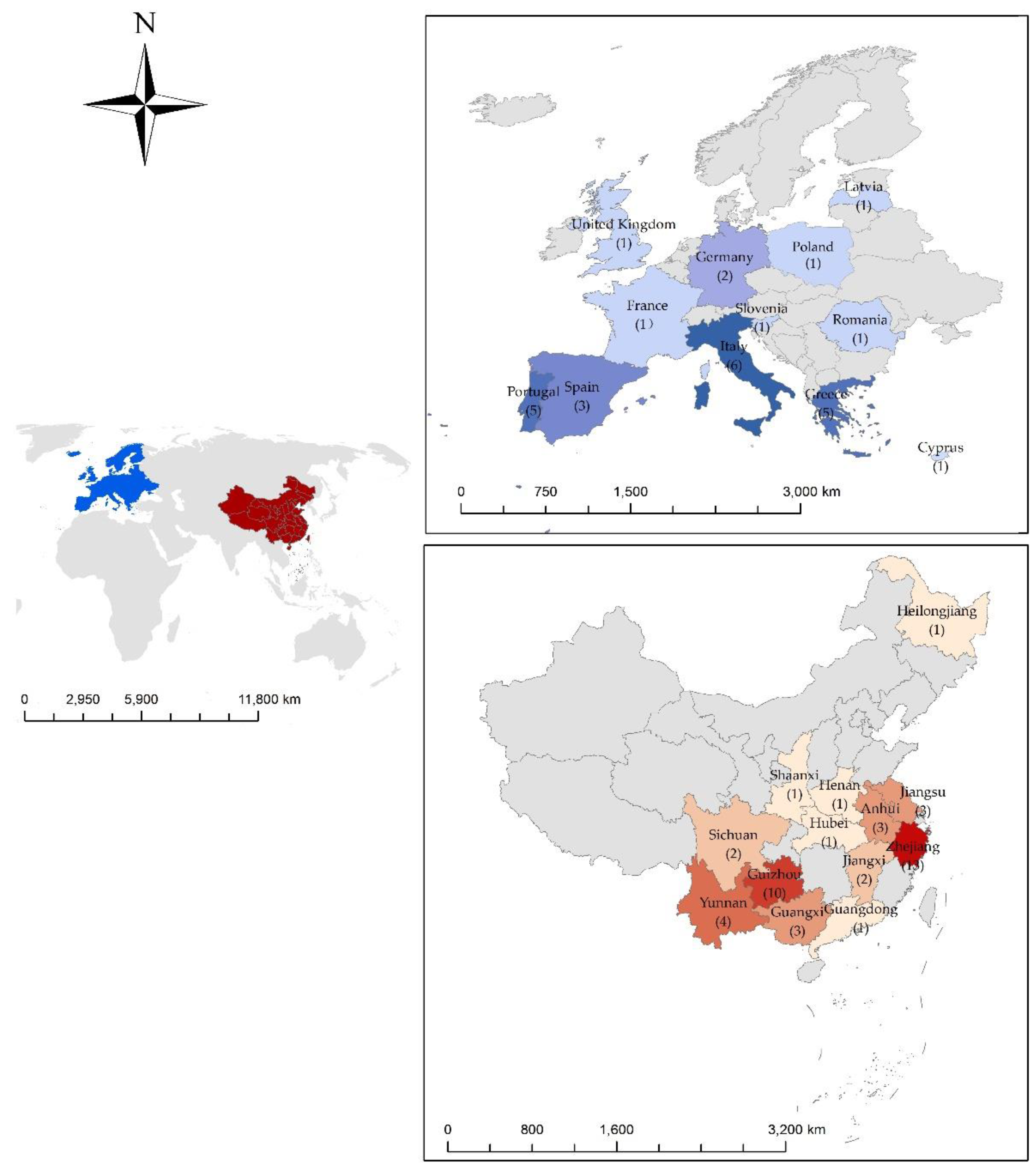

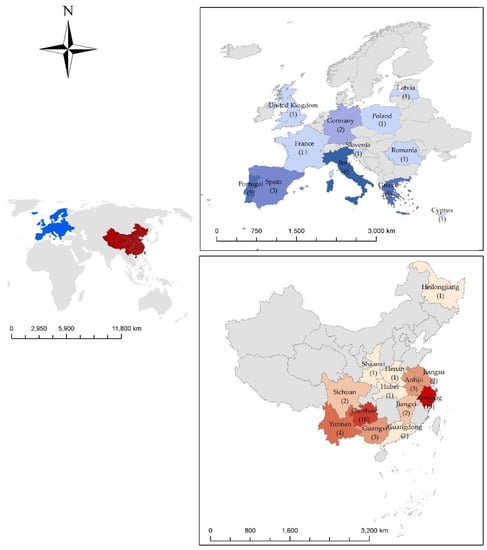

Based on the comparison between European and Chinese perspectives, the geographic distribution of case studies is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Geographic distribution of collected case studies in European and Chinese context. Authors’ elaboration based on map provided by Esri [42].

In European context, the case study villages were from Italy (21%), Portugal (17.8%), Greece (17.8%), Spain (10.7%), Germany (7.1%), Cyprus (3.5%), the UK (3.5%), Slovenia (3.5%), Latvia (3.5%), France (3.5%), Romania (3.5%), and Poland (3.5%) (Figure 2). It can be seen that in Southern Europe is the main area where the case study villages are distributed, due to the complex rural realities these areas have faced. On the one hand, rural development in Southern Europe highly relies on agriculture and also faces serious environmental degradation and depopulation [43]. On the other, it is the place where the rural cultural landscape value and rural tourism have been widely regarded as key-tools for local development [44].

In Chinese context, the case study villages were concentrated mainly in the eastern coastal areas, such as Zhejiang (28%), Anhui (6.6%), Jiangsu (6.6%) Provinces, and southwestern areas, such as Guizhou (22%) and Yunnan (8.8%), where a variety of ethnic minorities live (Figure 2). The case study villages distributed in the Southeast part of China were the places where heritage-led development has served for the rural revitalization program since 2000s [45]. Other cases were distributed in the Southwest because it is the area where the situation of historical villages has been characterized by, on one side, a variety of minority groups inhabit thus nourished historical villages containing different cultural characteristics, and on the other side, the area has been affected by severe poverty for a long time. Therefore, this area became the place where the scholars could conduct field surveys.

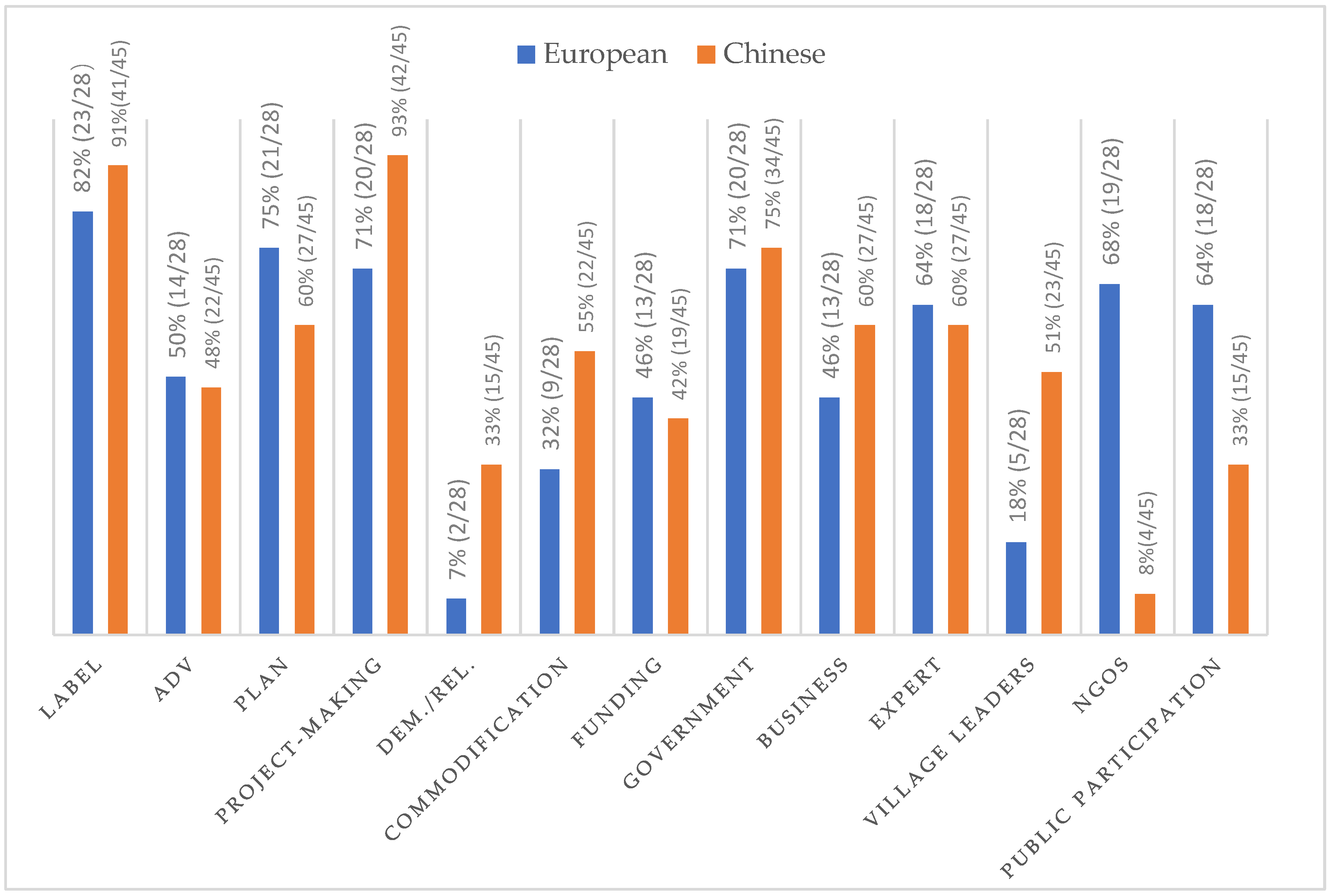

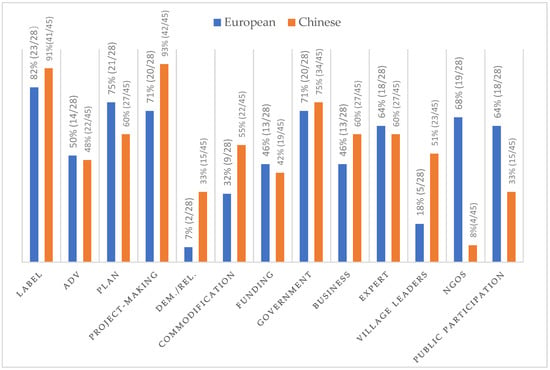

In addition, based on the comparison between European and Chinese perspectives, the main themes are shown in summary Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Main themes and percentages of case studies based on comparison between the European and Chinese contexts. (Authors’ elaboration.) Note: ADV stands for “advertisement”; DEM./REL stands for “demolition/relocation”; NGOS stands for “non-governmental organization”.

A closer look at each of the mentioned topics helped us to better understand the characteristics of the current European case studies. Villages recognized with designations of different levels, from international to local (e.g., UNESCO historical agricultural sites, ecomuseums, “most beautiful villages” in France, etc.) were included in 23 cases out of 28 (82%). In 14 cases out of 28 (50%), the villages had been advertised intentionally, and in 21 cases out of 28 (75%) there were spatial plans to address preservation and/or physical space transformations. Two cases out of 28 (7.4%) had experienced demolition and relocation, 9 cases out of 28 (32%) had experienced commodification through tourism development, and 13 cases out of 28 (46%) had faced funding issues. Additional reading was focused on the stakeholders involved. It was noted that 20 case studies out of 28 (71%) had regional and municipal governments as authorities intervening in rural heritage preservation and management. The role of businesses was found to be relatively modest, and was present in 13 case studies out of 28 (46%). Expert groups play a relevant role in rural heritage preservation and management, and were present in 18 case studies out of 28 (64%), and NGOs were present in 19 cases out of 28 (68%). Finally, concerning the involvement of public participation, 18 cases out of 28 (64%) addressed public participation to different degrees.

In the Chinese context, as can be seen in Supplementary Table S2, 41 case study villages out of 45 (91.1%) had different kinds of labels for their historic, cultural, and environmental characteristics, and 22 case studies out of 45 (48%) had been advertised intentionally as a development strategy. Moreover, 27 case study villages out of 45 (60%) underwent spatial planning to guide preservation and/or spatial transformation, 42 case studies out of 45 (93%) took on projects concerning both preservation and renovation, and 15 cases out of 45 dealt with demolition and relocation (34%). It is noteworthy that 25 case studies out of 45 (55%) were subjected to a tourism-oriented approach characterized by commodification, which occurred in most cases around 2000. In 18 of the case studies out of 45 (42.2%), funding was an issue in the preservation process.

Concerning the stakeholders, governments (75%), expert groups (60%), and businesses (50%) were the three most common stakeholder groups involved, followed by village leaders (68%). Village-owned, county-owned, and private enterprises are three types of businesses actively involved in planning, project-making, and commodification in rural built-heritage preservation in China. In this context, it is noteworthy that in only 8.8% of case studies were NGOs involved in preservation and development, and there was a minimal amount of public participation described in the case studies (33%).

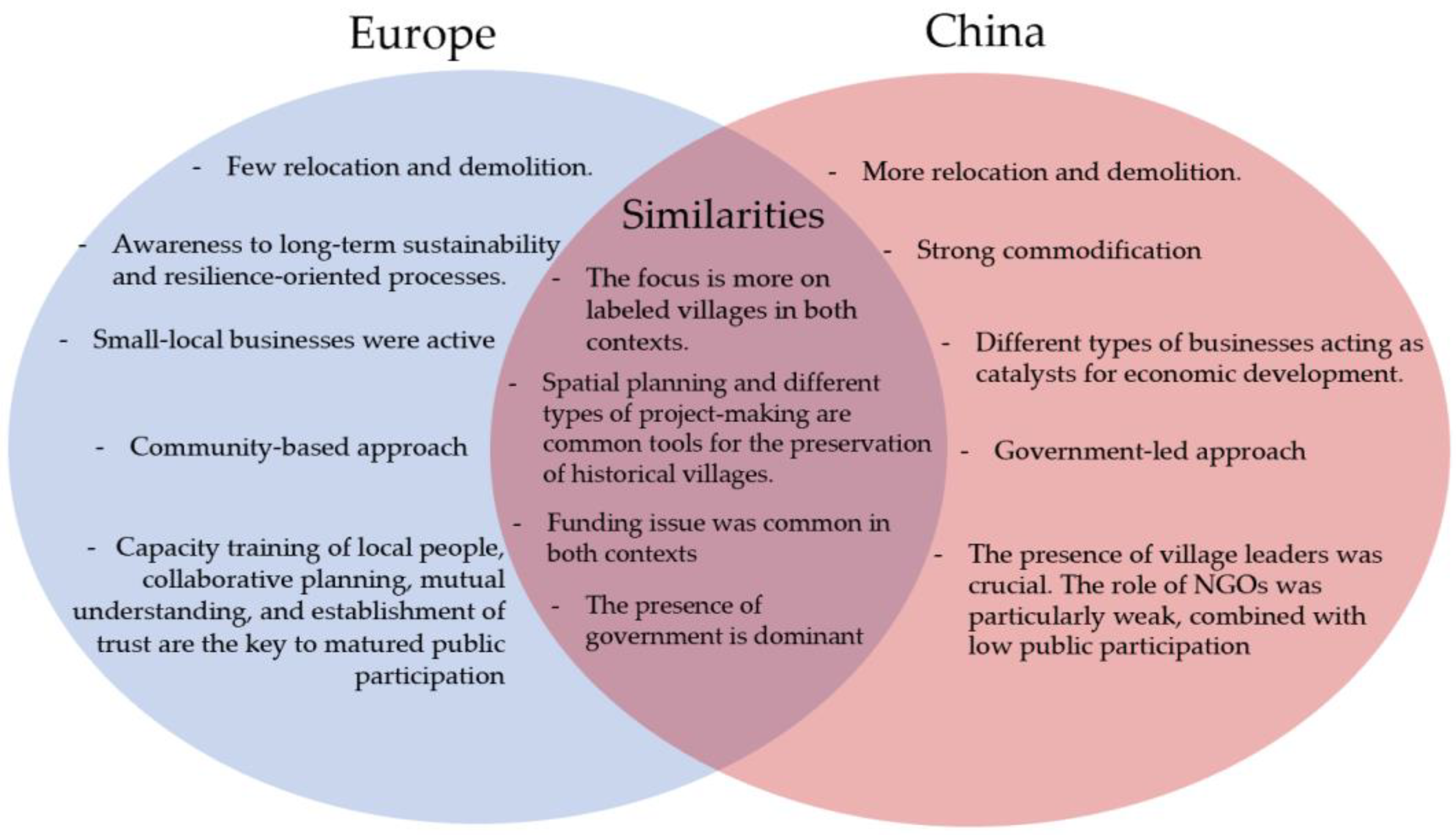

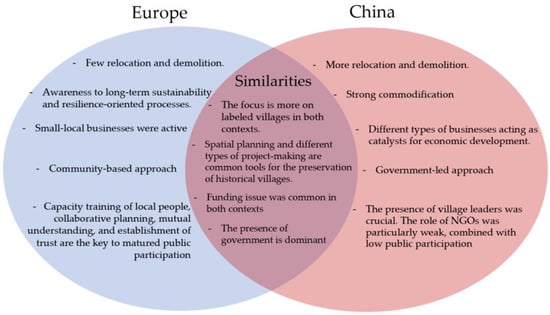

The similarities and differences are shown in Figure 4. The similarities are as follows:

Figure 4.

The similarities and differences of the case study villages in the two contexts. Author’s elaboration.

(1) The current focus in academia is more on those labeled villages that have obtained designation and recognition at different levels. This is due to the expert-led heritagization process, and the evaluation systems used for their selection, which have been promulgated globally since the last century [46]. This means that there is a lack of investigation regarding anonymous villages and communities. (2) Spatial planning and different types of project-making have been common tools for the preservation of historical villages in both contexts. (3) Funding issues were common in both contexts, but were more relevant in the Chinese case studies. (4) The presence of governments at different levels was dominant, as they provide operational solutions and human and financial resources in the rural heritage preservation process. Moreover, they often played a crucial role in the designation process [17].

The differences are as follows: (1) Compared to the European cases, the Chinese case studies experienced more relocation and demolition. (2) Commodification was rather strong in the Chinese context. (3) Different types of businesses acting as catalysts for local development were evident in case studies from China. (4) These data show that the preservation of Chinese rural heritage has essentially been characterized by authorized discourse and a government-led approach, although some bottom-up practices have emerged, and there is extended stakeholder involvement. (5) Village leaders were present in the historical village preservation process, while on the other hand, the role of NGOs was particularly weak, combined with low public participation. In addition, for their part, communities and social organizations have been significantly powerless. In the next section, the extended literature review on the topics and selected cases is described in order to better explore the state of the art in rural heritage preservation from both the European and Chinese perspectives.

3.2. Case Studies of European Rural Heritage Preservation

Heritagization is guided by and has an impact on the stakeholders that make up the social, political, and institutional context [47]. The European cases showed that in the process of heritage preservation and management, public–private partnerships through multistakeholder collaborations can be achieved according to different cultural contexts and social ties [22]. In the next sections, European cases in the heritage preservation in rural areas are reviewed and categorized as follows: (1) labeling, planning, and project-making; (2) contextualizing local communities; and (3) analyzing public–private partnerships.

3.2.1. Labeling, Planning, and Project-Making

In Europe, several positive cases of labeled villages have involved a mature planning technique and decision-making process. In Valverde de Burguillos, Portugal, an exploratory study was conducted using a multidisciplinary approach, including public participation, to support the Heritage Information System so as to prepare a strategic plan for rural heritage management [48]. Similarly, villages labeled as “the most beautiful villages of France” by the independent association Les Plus Beaux Villages de France [21] demonstrate participatory governance ideals and practices, imbuing the places with value and a sense of place through preservation and restoration initiatives. Based on this bottom-up approach involving multiple stakeholders, rural tourism has been able to link heritage preservation and local development by enhancing the economy [21]. In Latvia and Slovenia,, heritage management includes analyses and strategies spontaneously developed by citizens that have been encouraged to help shape heritage communities [49,50]. The case of Wisniowa, Poland, showed that rural heritage preservation and development was merely a process of conflict resolution by reconciling stakeholders [51]. A value-based, people-centered approach was also carefully tested in the Ruritage project. The program provides a detailed procedure to form a participatory process for heritage-based development in different rural heritage hubs embedded into different cultural–natural characteristics [23].

In conclusion, local community awareness is the key aspect that differentiates short-term profit-making from long-term sustainability and resilience-oriented processes. A look at stakeholders and interactions in the case study villages was necessary, and this is discussed in the next section.

3.2.2. A Stakeholder Analysis

Different levels of government play an undeniable role as leading authorities in the elaboration and execution of planning regulations for heritage preservation. In the European context, municipalities have been the main government bodies to intervene directly in heritage preservation and management processes. In Italy, the municipality of La Morra, in the province of Cuneo, Piedmont, updated its strategic town plan in accordance with the UNESCO guidelines and to involve communities [52]. In Wisniowa, Poland, the municipality was active in leading preservation and renovation projects [51]. In France, municipalities, with several special committees, are entitled to apply for labeling for their villages to boost tourism development [21]. The impact of reciprocal interactions and attractiveness among local cooperative partners and public bodies on preserving rural heritage has been also reported in the villages of Jelgava County, Latvia [49]. It should be noted that municipalities, as the governmental body working at the front line in both daily spatial planning practices and heritage preservation, may be criticized if they are revealed to be paternalistic, as occurred in villages in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany [53].

Concerning businesses in the case study villages in Europe, small local businesses were moderately present [49,51,54,55]. Small-scale, family-run businesses indicate the economic sustainability of local societies [55,56]. Others were supported by public–private subsidies [57]. Conversely, public-owned enterprises were powerful but can be failed in their implementation of strategies to attract, incentivize, and retain tourism-oriented businesses in Mertola, Portugal [47].

In Europe, the term “elite” indicates social and historical progress and the transformation of the ancien régime social order (based on principles of heredity) into the mass societies of the 19th century [58]. The emergence of modern election mechanisms brought contemporary debates about class and power to the countryside [58]. Reviewing the selected papers and case studies in the European context, elitism was rarely found. A few studies observed activities by elites in heritage preservation as they attempted to select which history to preserve [59].

Regarding the role of expert groups in historical villages, we draw on the ideas of Giddens [60], who believed that the concept of expertise in heritage studies is strictly associated with the modern idea of risk management, which advocates professionalization of those who possess knowledge in different areas related to heritage. For instance, planners and architects become experts, intervening in the process of heritage preservation with their knowledge [61]. Despite some studies showing disparities between experts and residents regarding what shape heritage should take in a given community, experts have been able to transmit heritage knowledge to communities in labeled villages through an authoring process [62]. In recent decades, some cases have also mirrored the communicative turn of the experts in planning, as they are committed to creating dialogue between the public and private spheres [52], supporting managerial processes [47], and providing smart and light solutions [59] instead of translating social issues into spatial regulations and rigid design solutions.

Issues related to community interests form the core part of heritage management in the European context. Community participation is an essential factor in empowering long-term sustainability [63,64,65]. It was noted that the existence of different classes and social groups within the same community can produce different narratives about the same heritage site (place), as “community in terms of a homogeneity and cohesiveness can hardly exist” [66]. Such differentiation in recognition of value can be found in societies where civic power is active through the process of wide social engagement. In Apulia, Italy, different perceptions about and attitudes toward the reuse and preservation of local farmhouses were identified based on the relationships between farmers and agricultural sectors [67]. The authors of [63] showed that expert knowledge and residents’ perceptions were able to reach agreement in Mount Pelion, Greece, where different types of residents supported recognition of the value provided by experts from their everyday experiences and personal memories. As reported in [68], a community in Sortelha village, Portugal, was able to recognize both benefits and costs during the preservation and tourism development process led by European and country-level rural redevelopment programs. The authors of [67] noted that residents appear to be more sensitive to decaying heritage than tourists due to their familiarity with the built environment, and that this varies between young and old generations.

It should also be noted that the relationship between heritage, community, and place has always changed over time, as people’s contextualization and social ties are always transforming [69]. Strong engagement by young people is central to shape future communities [37]. From this perspective, the individual dimension is also valued as part of the process, as shown in the case of Huete, Spain. This case study showed how to empower the emotional values of individual citizens to enhance and support networks that can channel human and economic resources to create positive social changes [57]. All of the diverse values and aspects mentioned above contribute to building an epistemology of heritage.

3.2.3. Analyzing Public–Private Partnerships

As previously discussed, different types of businesses as for-profit actors were present in the study cases in Europe. Connections between public institutions, business sectors, and communities fuel public–private partnerships that can provide more effective solutions [70,71]. Advocating for a sustainable approach to rural heritage preservation by caring communities, the authors of [72] selected a cultural landscape site in Northern Germany as a case study, identifying the complex and dynamic relations among stakeholders in collaborative heritage management. They asserted the central role of “collaborative capacity” [72] among stakeholders and in public–private partnerships, which was defined by Beckley as “the collective ability of a group to combine various forms of capital with institutional and relational contexts to produce desired outcomes” [73]. It is essentially based on the “civic culture” expressed by those who “meet, discuss, exchange, and accomplish tasks in the public sphere”.

Heritage NGOs have been assigned such a role, as they highlight the current demands of linking diverse parties, functions, expertise, and roles in order to effectively handle cultural heritage preservation [74]. In Greece, the presence of NGOs is relevant, as they have been able to enhance knowledge transmission, support production processes, and empower tertiary activities within local communities in three agricultural heritage landscape sites [75]. Nevertheless, the position of NGOs should be critically analyzed, as they are recognized as having expertise and thus may decide, in some cases, what and whose heritage to preserve [59]. This is what has happened in Viscri, Romania, where an NGO took the lead in addressing restoration projects despite the criticized elite-led vision they followed. In conclusion, the studied European cases showed that place-based and people-oriented approaches should be suggested, as the conception of rural heritage goes beyond a reductionist aesthetic and the functional value of certain groups. These cases support the construction of a multitemporal space that can be witnessed and socially experienced, and ought to be commemorated [76,77]. Along with the time and continued commitment to community development such an approach requires, capacity training of local people, collaborative planning, mutual understanding, and establishment of trust among stakeholders are keys to improving community participation [74].

3.3. Rural Heritage Preservation in the Chinese Context

3.3.1. Labeling, Planning and Project Making

As shown in Supplementary Table S2, heritage preservation activities in China have largely followed a government-led approach [25] in which heritage has been used as an apparatus controlled by the state [17]. Most villages are labeled for historical, cultural values, thus subjected to the authoritative method of preservation and management. This is something intrinsically associated with the country’s political and cultural traditions [8,16].

Several debates have arisen regarding the government-led heritage practices of China’s authoritarian market-socialist governance [16,18]. The authors of [16] saw cultural heritage preservation in China as an activity in which conflicts and dissonance between the state and the market, experts, and people outside and within communities are constantly changing within the process of evolving ideological circumstances. This process shows what a country, and those in power within it, want to preserve and remember of the past through patriotic education and people’s attendant imagery [15]. The authors of [18] pointed out that heritage is used as a governance tool to legitimize inclusion and exclusion, as objects and places can be changed from utilitarian things into items representing progressive social improvement expressed in spatial planning. In fact, some authors have argued that in the recent Chinese institutional narratives, the emphasis on enhancing soft power, modernizing the countryside, alleviating poverty, and promoting the multi-ethnicity of the country are subordinations of this goal, which has been performed in physical transformations through project-making processes [78,79,80]. Thus, being driven by profit seems to be an essential characteristic of the Chinese heritage preservation approach, bringing on an identity crisis in many historical villages [17,81].

3.3.2. A Stakeholder Analysis

Based on the literature review (Supplementary Table S2), stakeholders involved in rural cultural heritage preservation in China were identified as governments at and above the county level, townships, expert groups, village leaders, and communities.. These are discussed in the next section.

As described in [82], county administrations are “the power center of the local state” where traditional and contemporary power practices in rural China were systematically embedded [82]. As crucial actors at the local level in the Chinese countryside, county-level governments and their performance vary significantly with regard to rural cultural heritage preservation, as shown in current studies [8,36,38,83]. Once countywide planning is defined, it seems that it is the township that informs villages about the approved projects according to the county program. However, as noted in [40], the attitude of the county government can potentially be influential when branded villages and star projects can help promote the cadres of the county or its government.

Through the review of the case study villages, it was found that different types of enterprises have been developed and are involved in rural cultural heritage preservation, including village-owned [36], private [17,84], and state-owned (especially county-owned) [28,83] enterprises. Using the cases of Zhujiajiao and Lanting villages in Zhejiang Province, the authors of [84] critically unraveled the representative practices of hegemonic private companies in the incorporation of recreational industries into relocated heritage assets based on the mindset of conservation by relocation. This was a direct result of negotiations between local governments and private enterprises guided by expert validation within a top-down framework of heritage practice. In other cases, where abundant social capital has emerged at the grassroots level, some village-level businesses have appeared, improving economic conditions, profit-making, and local community empowerment [36]. Moreover, the so-called iron triangle between the Chinese state, the Communist Party, and public/private/mixed enterprises has been confirmed to shape political connections and administrative experiences in the process of achieving leadership [85]. This strategy appears to benefit business promotionally and reciprocally, as leaders are promoted based on their financial performance. The authors of [36] analyzed the management system of Hongcun, Anhui Province, as a tourist destination in terms of corporate leasing, and identified problems in the current management system of the SOE–government alliance. This highlights the crucial role of SOEs and their relationship with the local government. A study focused on Upper Langde village, Guizhou Province, criticized how it was transformed from an authentic ethnic village to a tourism destination by the county government and a county-owned tourism company [86].

The experts involved in heritage preservation often include professionals who can talk to both authorities and local communities at the same time, conveying their professional knowledge [37,87]. Similarly to some cases in Europe, the active attitude that experts had about social engagement in heritage preservation was the subject of hot debate in the selected case studies [41,78,87]. Experts can exercise their capacity by actively organizing cultural events [87] and realizing the government’s objectives regarding the protection and development of physical spaces [88,89]. Supported by the government and the community, expert groups can be efficient in launching and coordinating public participation [78] and building a shared platform for reciprocal dialogue and decision-making between the top-down and bottom-up approaches [41,87,88]. The authors of [90] identified the overlapping roles of experts and NGOs in efficiently leading post-catastrophe revitalization projects in a historic Qiang village in Sichuan Province. Among the experts, architects and planners can build a sense of trust in the local community by fostering collaboration between professional competencies and local knowledge through effective communication and sophisticated implementation [88]. Conversely, some negative impacts of expert groups were also described in the literature. Studies of the listed villages in Zhejiang have shown that the experts tend to put material interests before community interests in supporting the government [16]. This was also proven in cases where the government had a strong presence, such as the WHL site at Hongcun [36].

Empirical studies in the examined literature showed both the merits and shortcomings of village leaders in rural cultural heritage preservation. In Chinese context, when referring to leaders in a village, this generally seems to mean elite families and village cadres. Local elites in China, even today, are expressions of local kinship and clans [91,92]. The growth of their members is the basis for further social status promotion, which affects the rural governance of local societies [93]. The authors of [7] observed that kinship groups have been active in carrying out heritage activities and forming their own discourse on history while challenging the officially defined narratives. Such coalitions are important for the generation of social capital through family networks, achieving the aim of community building, which reconsolidates their role as leaders. The authors of [87] pointed out that cadres and elites sometimes maintain close ties to local communities, playing the role of “heritage middlemen” [87]. In some cases, the recruited external entrepreneurship and technical assistance came from local elite families [38]. In fact, the village head in Yuanjia village, Shaanxi Province, worked in a city, and this experience provided him with skillful ideas about how to develop the village by adopting the rural tourism approach [38]. He used his personal network to attract external capital and establish cooperatives in the village [38]. Nevertheless, negative aspects were also found, as villagers can hardly control their leaders, especially when they have potential opportunities to make profits for themselves [94]; this highlights the crucial aspect of integrating and coordinating the responsibilities of government agencies and empowering family networks.

In the Chinese context, community engagement seems to be rarely implemented at any stage of village development; in some cases in the literature, communities that expressed their wishes clearly were seen as being in conflict with the authorities [16]. The Chinese approach is characterized by the robust presence of government interventions and external capital to boost tourism. In Yunnan, the authors of [15] observed that the situation of poor people was bleak because they received few benefits from tourism development, as their voices were absent from the decision-making and management processes. Heritage-led development includes dissonance and conflict, which can only bring short-term benefits and commodification to the community [15]. The authors of [95] took the rice-terraced villages of Hani, a World Heritage Site (WHS), as a case study, and reported that the phenomenon of self-gentrification was noted in the “proactive responses of residents in gentrifying the community” [95]. Nevertheless, some innovative practices with Chinese characteristics [96] have presented initiatives of community engagement. For example, instead of recalling community participation, the authors of [36] used a communal participation framework to describe the operational patterns in two historical villages designated as WHSs. They showed that a lack of community participation in decision-making can somehow be substituted by the latter interest-sharing strategy. A similar approach of sharing interests instead of making decisions emerged in Upper Langde village, Guizhou Province, where a work point system and labor division mechanism brought “small and slow growth” [86] to the community. The latter can enhance community participation and sustainable development at the same time.

3.3.3. Coalitions and Tensions in Government-Led Approach

In China, heritage-led development of historical villages was an intentional decision involving both the preservation of cultural heritage and the development of socioeconomic conditions in a government-led approach. The initial attempts can be traced to the late 1990s in Guizhou, Yunnan, and Guangxi Provinces, Southwest China, with the development of ecomuseums [80]. Their introduction was characterized by a hybridization of international experiences and local interpretations, despite criticism related to the commodification process led by local governments [80,81]. In some cases, such an approach did bring economic benefits to local communities [15]. However, in most cases, the villages became commodities for urban users to develop tertiary sectors in the countryside [8], raising a debate about the authenticity of rural heritage [84], gentrification, and self-gentrification of communities [95]. As a result, many historical villages became more vulnerable to massive rural tourism and the construction of a socialist countryside after being placed on different conservation lists [94].

Tourism development and commodification often seem to start soon after historical villages are labeled, essentially attracting the interests of local networks. And coalitions and tensions are formed, as authors of [8] observed that the listing of cultural heritage in the Chinese context often relies on good connections with the experts and family clusters who represent heritage practices. In this way, the experts can contribute to identifying heritage once a village is designated, apart from the governments’ financial support, with subsequent spontaneous commercial activities bringing modest profit [17]. Such a process implies that branding, competition, model-making, and conflict should be highly valued in advance by different types of stakeholders, but especially by governments.

Apart from the macro policies using heritage preservation as a catalyst for economic development at a national level, the stakeholders analyzed above often form tensions and coalitions at and below county-level administration. In fact, county governments are the entities responsible for recommending villages for different lists and nominations, as well as for their development plans and detailed plans for conservation and renovation within the administrative boundaries [94]. In this way, county governments are very influential, as they can decide which villages and projects to invest in and how. In addition, as noted in [94], when a top-down approach is used, ignoring the village’s local necessities and conditions, it can lead to potential project and task “failures”, thus missing the opportunity for fruitful contact between government intervention and bottom-up innovation. In addition, after deciding which villages to invest in, organizing state-owned enterprises (SOEs) has been a common choice for county governments, as this approach can accelerate investment and enhance the achievement of outcomes. This approach, in fact, can strongly influence the phases of plan formulation, implementation, construction, and upcoming management [97]. County-owned enterprises, as the products of coalitions between county governments and enterprises, have affected the transparency and efficiency in heritage management, exposing the government’s actions in pursuing its own short-term interests [97].

Moreover, from the perspective of policy-making and implementation, the authors of [97] note that in the top-down planning system in China, characterized by a fast-changing social and political environment, the traditional urban planning paradigm has been forcefully transplanted into a fragmented regulatory planning system aimed at modernizing the countryside. Against this background, experts are rarely prepared to work in such challenging and dynamic conditions. As a result, even though some positive experiences have provided an impetus for repositioning the role of experts in empowering communities, their relationships with the authorities involved in heritage preservation networks remain critical.

Concerning the critical role of village leaders, a lack of confidence and a history of difficult cooperation often appeared in the literature, since villagers see cadres as agents of the state rather than representatives of the community [98]. Sometimes, local elites and village cadres seem to form a consolidated alliance to disseminate governance and state-related interests in the countryside, using networks and informal rules, and taking care of local public welfare [99]. As reported in [94], the complex role of elites puts them in the role of authorities and experts based on local traditional kinship and power networks.

Based on the above-mentioned dynamics amongst stakeholders in rural cultural heritage preservation in Chinese context, community’s voice can be hardly heard neither in decision-making nor in the follow-up project making and management process. This is contrary to what has emerged in European case studies, as the rapid urbanization and social-economic transformations occurred in China do not provide so much space to continued commitment and gradually formed interaction mechanism for community. Necessary praxis to enhance mutual trust among stakeholders about the acknowledgement on cultural heritage preservation have been lacking.

4. Discussion

Insights emerged from the comparative analysis of case study villages in the European and Chinese context. Concerning the case studies in Europe, different practices have been characterized by vital civil participation in the cultural heritage preservation of historical villages [52], and this has left space for the involvement and interactions of different stakeholders and bottom-up management initiatives [52]. Moreover, an innovative, accountable management mechanism has emerged [23] based on effective capacity building by residents and governments’ willingness to be involved as much as possible in communities [48]. From the perspective of the private parties involved, it was found that small startups can avoid the government–business coalition and further enhance management transparency [49,52,53,77]. This should be reasonably suggested for rural cultural heritage preservation in other contexts. Concerning the issue of community engagement, current studies in the European context have examined differentiations within communities and the different values they generate [77]. Using the participatory method, dynamic interactions and effective capacity building [50] are nourished in a vibrant civic culture where the collective capacity of participation, negotiation, mutual understanding, and trust building is empowered [21,64].

Compared to Europe, some particularities were found in the cases from China, as follows: (1) Historical villages in China experienced more changes in terms of demolition and relocation, which brought serious transformations to the historic built environment and the cultural identity of local communities [8,36,41,94]. (2) The profit-oriented process was accompanied by the commodification of historical villages [15,36,79,81]. (3) Public participation and the presence of NGOs were relatively weak. (4) The roles of local governments, experts, and village leaders have been strongly characterized by Chinese-specific sociopolitical settings, further generating coalitions and tensions that affect the preservation and development processes [7,15,94]. The county government, as the power center of the local state, plays a dominant role in framing development strategies and spatial plans related to rural heritage preservation. The complicated role of local elites is similar to that described by the authors of [55], namely that they claim to have the power to define what ought to be preserved for the community. In some cases, local elites tend make profit through renovation projects under the guise of rural and cultural revitalization, due to the information gap between village leaders and ordinary inhabitants [99]. In addition, as revealed by the present research, the crucial relationship between local governments and enterprises [17], the expert groups delegated to realize economic development goals by planning and design [100]. The critical presence of local leaders [7,94], and weak community engagement [36] are issues that have been discussed by international and Chinese scholars, who have tried to provide suggestions on how to effectively manage rural cultural heritage.

These results are consistent with those of [15], which reported that the cultural heritage preservation and management processes in the Chinese context are government-led. In addition, a further step was taken to look at the processes and stakeholders involved in historical village preservation and development from a comparative perspective. In fact, compared to the European cases, the stakeholders in the Chinese cases had an ambiguous and difficult-to-control position in shaping the rural built environment amid fast-changing socioeconomic conditions. This should be understood both within the traditional Chinese rural governance framework and in terms of contemporary political inquiries into ongoing rural construction activities [38,40,41]. Both top-down and bottom-up approaches are important in heritage preservation and management, as only when both the institutional and authoritative powers and the grassroots and civic spheres collaborate together, the long-vision and resilient heritage management can then be achieved [101].

Some insights into the future of research should be drawn on the rise of new technologies and the multi-disciplinary approaches, which can benefit rural heritage preservation and management [102,103,104,105]. From the point of view of investigations on physical conservation, scientific analysis developed in archaeological studies is an inspiriation to enhance historical research and develop future interventions for historical villages. From the point of view of heritage preservation and management, further attention should be paid to how to establish shared platforms involving different types of stakeholders in the planning and design process based on the issues and networks noted above. It is crucial to educate and train societies about the effects and long-term sustainability that collaborative management of heritage can generate, and sufficient time and funding should be appropriately provided.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, based on a literature review of 73 case studies from 50 articles, the common features and differences between European and Chinese rural cultural heritage preservation and management are compared and discussed, paying attention to historical villages in both contexts. Using this method, rural heritage preservation in China can be better framed and analyzed for scholars engaged in both international and Chinese contexts.

The case studies in Europe showed the importance and the efficiency of wide social engagement in rural heritage preservation. This is based on an effective capacity building of different types of stakeholders, appropriate financial mechanism and different sets of values the civic society perceived and recognized during the rural heritage preservation and management process.

Cultivated against a particular sociopolitical background, the process of rural heritage preservation in China has been strongly impacted by the government-led approach. In this analysis, a difficult-to-control dynamic among stakeholders was shown through the systematic literature review. In some cases, different stakeholders can arrive at a common interest, but in most cases the voice of the community is hardly considered in the decision-making around rural cultural heritage preservation.

Inspired by the European case studies, the research reveals some key points that can enhance rural heritage preservation in China. Capacity building of different types of stakeholders, contextualized financial mechanisms and multiple values the civic society perceived and recognized during the rural heritage preservation and management process should be further studied and implemented case by case based on a historical-sensitive approach. In addition, the issues related to social capital and the policy arrangement in rural areas should be further addressed in the Chinese context.

This study has some limitations. First, the method for selecting papers and case studies might have been insufficient, as some studies sharing common goals with this research may not be categorized properly in the database. Some articles that were not in English but had regional importance might have been excluded from the samples, and future studies should not ignore their scientific value. Second, while this research demonstrates useful findings, these findings may not be applicable to other nations or cultures. In fact, case studies on the rural cultural heritage preservation practices of other cultural and geographical contexts (e.g., Africa, South America, North America, other Asian countries) should be further analyzed to obtain a holistic understanding of the topic from the international perspective, particularly considering cultural and political variations [106,107,108,109]. Additionally, considering the experiences in the European context, despite the relatively common cultural and policy conditions that countries share (e.g., the LEADER program that the European Union launched for its member countries in 1991 [110]), the diversity among rural cultural heritage management processes in different countries should be further considered. Third, the commonalities and differences between the European and Chinese contexts should be understood and contextualized with the help of an exploratory analysis of the legislation and policy-making of rural cultural heritage preservation.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/land11070982/s1, Table S1: Thematic table based on the literature review of case studies in European context.; Table S2: Thematic table based on the literature review of case studies in Chinese context.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.M.; methodology, Q.M.; formal analysis, Q.M. and F.A.; investigation, Q.M. and F.A.; resources, Q.M.; data curation, Q.M.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.M.; writing—review and editing, F.A.; visualization, Q.M.; supervision, F.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank the editor and the anonymous reviewers for their careful reading of the manuscript and their insightful comments and suggestions. The research is a part of the Ph.D. research of the first author; thus, the authors are grateful to the Voghera Angioletta for her comments on earlier versions of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- European Environment Agency. Briefing Agriculture. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/soer/2015/europe/agriculture (accessed on 5 June 2022).

- Pinto-Correia, T.; Menezes, H.; Barroso, L.F. The Landscape as an Asset in Southern European Fragile Agricultural Systems: Contrasts and Contradictions in Land Managers Attitudes and Practices. Landsc. Res. 2013, 39, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO (Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations). FAO in China, China at a Glance. Available online: https://www.fao.org/china/fao-in-china/china-at-a-glance/en/ (accessed on 5 June 2022).

- Beza, B.B. The aesthetic value of a mountain landscape: A study of the Mt. Everest Trek. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2010, 97, 306–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhzoumi, J.M. Unfolding Landscape in a Lebanese Village: Rural Heritage in a Globalising World. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2009, 15, 317–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe, European Rural Heritage Observation Guide—CEMAT. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/16806f7cc2 (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, Z. The reproduction of heritage in a Chinese village: Whose heritage, whose pasts? Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2015, 22, 228–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitzky, W. Mediating heritage preservation and rural development: Ecomuseum development in China. Urban Anthropol. Stud. Cult. Syst. World Econ. Dev. 2012, 41, 367–417. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23339812 (accessed on 5 June 2022).

- Charter of the built Vernacular Heritage. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/en/participer/179-articles-en-francais/ressources/charters-and-standards/164-charter-of-the-built-vernacular-heritage (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Council of Europe Landscape Convention. Available online: https://www.coe.int/web/landscape/home (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- State Council of PRC, Outline of the 14th Five-Year Plan (2021–2025) for National Economic and Social Development and Vision 2035 of the People’s Republic of China. Available online: https://www.fujian.gov.cn/english/news/202108/t20210809_5665713.htm (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Huang, Y.; Li, E.; Xiao, D. Conservation Key points and management strategies of historic villages: 10 cases in the Guangzhou and Foshan Area, Guangdong Province, China. J. Asian Arch. Build. Eng. 2021, 21, 1320–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler-Estrela, A. Cultural Landscape Assessment: The Rural Architectural Heritage (13th–17th Centuries) in Mediterranean Valleys of Marina Alta, Spain. Buildings 2018, 8, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, S.; Peng, H. Tourism development, rights consciousness and the empowerment of Chinese historical village communities. Tour. Geogr. 2014, 16, 772–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumenfield, T.; Silverman, H. Cultural Heritage Politics in China; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Svensson, M. Evolving and Contested Cultural Heritage in China: The Rural Heritagescape. In Reconsidering Cultural Heritage in East Asia; Matsuda, A., Mengoni, L.E., Eds.; Ubiquity Press: London, UK, 2016; pp. 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakes, T. Heritage as Improvement. Mod. China 2012, 39, 380–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakes, T. Villagizing the city: Turning rural ethnic heritage into urban modernity in southwest China. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2016, 22, 751–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gorp, B.; Renes, H. A European Cultural Identity? Heritage and Shared Histories in the European Union. Tijdschr. voor Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2007, 98, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swenson, A. The Rise of Heritage: Preserving the Past in France, Germany and England, 1789–1914; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ducros, H.B. Confronting sustainable development in two rural heritage valorization models. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 25, 327–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egusquiza, A.; Zubiaga, M.; Gandini, A.; de Luca, C.; Tondelli, S. Systemic Innovation Areas for Heritage-Led Rural Regeneration: A Multilevel Repository of Best Practices. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, C.; López-Murcia, J.; Conticelli, E.; Santangelo, A.; Perello, M.; Tondelli, S. Participatory Process for Regenerating Rural Areas through Heritage-Led Plans: The RURITAGE Community-Based Methodology. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Cenci, J.; Becue, V.; Koutra, S.; Liao, C. Stewardship of Industrial Heritage Protection in Typical Western European and Chinese Regions: Values and Dilemmas. Land 2022, 11, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Krishnamurthy, S.; Roders, A.P.; van Wesemael, P. Community participation in cultural heritage management: A systematic literature review comparing Chinese and international practices. Cities 2020, 96, 102476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrientos, F.; Martin, J.; De Luca, C.; Tondelli, S.; Gómez-García-Bermejo, J.; Casanova, E.Z. Computational methods and rural cultural & natural heritage: A review. J. Cult. Herit. 2021, 49, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, S.A.; Richards, J.; Fatorić, S. Climate Change and Cultural Heritage: A Systematic Literature Review (2016–2020). Hist. Environ. Policy Pract. 2021, 12, 434–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, M.; Maags, C. Mapping the Chinese Heritage Regime. In Chinese Heritage in the Making; Amsterdam University Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 11–38. [Google Scholar]

- Pranckutė, R. Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus: The Titans of Bibliographic Information in Today’s Academic World. Publications 2021, 9, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čeginskas, V.L. The Added European Value of Cultural Heritage. The European Heritage Label. Santander Art Cult. Law Rev. 2018, 4, 29–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, R. Assessing values in conservation planning: Methodological issues and choices. In Assessing the Values of Cultural Heritage; Getty Institution: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 5–30. [Google Scholar]

- Ashworth, G. Preservation, Conservation and Heritage: Approaches to the Past in the Present through the Built Environment. Asian Anthr. 2011, 10, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Operational Guidelines for the implementation of the World Heritage Convention. 2019. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/guidelines/ (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Millars, S. Stakeholders and Community Participation. In Managing World Heritage Sites; Routledge: London, UK, 2006; pp. 37–54. [Google Scholar]

- CEMR of Europe. Local and Regional Government in Europe. Structure and Competences. Available online: https://www.ccre.org/docs/Local_and_Regional_Government_in_Europe.EN.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Ying, T.; Zhou, Y. Community, governments and external capitals in China’s rural cultural tourism: A comparative study of two adjacent villages. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Liu, G.; Zhou, J.; Wang, J. Identifying the Critical Stakeholders for the Sustainable Development of Architectural Heritage of Tourism: From the Perspective of China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Wu, B. Revitalizing traditional villages through rural tourism: A case study of Yuanjia Village, Shaanxi Province, China. Tour. Manag. 2017, 63, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Dela Cruz, M.J.; Min, Q.; Liu, M.; Zhang, L. Conserving Agricultural Heritage Systems through Tourism: Exploration of Two Mountainous Communities in China. J. Mt. Sci. 2013, 10, 962–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlers, A.L.; Schubert, G. “Building a New Socialist Countryside”—Only a Political Slogan? J. Curr. Chin. Aff. 2009, 38, 35–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, X.; Lin, J.; Li, Y. Beyond government-led or community-based: Exploring the governance structure and operating models for reconstructing China’s hollowed villages. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 93, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Official Website of the Standard Map Service System of China. Available online: http://bzdt.ch.mnr.gov.cn (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Mergos, G.J.; Donatos, G.S. Agriculture and the rural economy of Southern Europe at the threshold of European integration. J. Area Stud. 1996, 4, 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, D. Rural tourism development in southeastern Europe: Transition and the search for sustainability. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2004, 6, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, W.; Lo, K. Back to the Countryside: Rural Development and the Spatial Patterns of Population Migration in Zhejiang, China. Agriculture 2021, 11, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L. Uses of Heritage; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- García-Delgado, F.; Martínez-Puche, A.; Lois-González, R. Heritage, Tourism and Local Development in Peripheral Rural Spaces: Mértola (Baixo Alentejo, Portugal). Sustainability 2020, 12, 9157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredholm, S. Making Sense of Heritage Planning in Theory and Practice: Experiences from Ghana and Sweden; University of Gothenburg, Acta Universitatis Gothoburgensis: Goteborg, Sweden, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Paula, L.; Kaufmane, D. Cooperation for Renewal of Local Cultural Heritage in Rural Communities: Case Study of the Night of Legends in Latvia. Eur. Countrys. 2020, 12, 366–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nared, J.; Erhartič, B.; Visković, N.R. Including development topics in a cultural heritage management plan: Mercury heritage in Idrija. Acta Geogr. Slov. 2013, 53, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feuer, H.N.; Van Assche, K.; Hernik, J.; Czesak, B.; Różycka-Czas, R. Evolution of place-based governance in the management of development dilemmas: Long-term learning from Małopolska, Poland. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2021, 64, 1312–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferretti, V.; Gandino, E. Co-designing the solution space for rural regeneration in a new World Heritage site: A Choice Experiments approach. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2018, 268, 1077–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, O. Making Landscapes of (Be)Longing. Territorialization in the Context of the Eu Development Program Leader in North Rhine-Westphalia. Eur. Countrys. 2021, 13, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, F.P.; Ramos, R.A.R. Heritage Tourism in Peripheral Areas: Development Strategies and Constraints. Tour. Geogr. 2012, 14, 467–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vehbi, B.O.; Yüceer, H.; Hurol, Y. New Uses for Traditional Buildings: The Olive Oil Mills of the Karpas Peninsula, Cyprus. Hist. Environ. Policy Pract. 2018, 10, 58–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belliggiano, A.; Bindi, L.; Ievoli, C. Walking along the Sheeptrack…Rural Tourism, Ecomuseums, and Bio-Cultural Heritage. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintana, D.C.; Díaz-Puente, J.M.; Gallego-Moreno, F. Architectural and cultural heritage as a driver of social change in rural areas: 10 years (2009–2019) of management and recovery in Huete, a town of Cuenca, Spain. Land Use Policy 2022, 115, 106017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugent, S.L.; Shore, C. Elite Cultures: Anthropological Perspectives; Routledge: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Klimaszewski, C.; Bader, G.E.; Nyce, J.M.; Beasley, B.E. Who Wins? Who Loses? Representation and ‘Restoration’ of the Past in a Rural Romanian Community. Libr. Rev. 2010, 59, 92–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddens, A. Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age; Stanford university press: Redwood City, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, R. Heritage: Critical Approaches; Routledge: Abingdon, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gallou, E.; Fouseki, K. Applying social impact assessment (SIA) principles in assessing contribution of cultural heritage to social sustainability in rural landscapes. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 9, 352–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katapidi, I. Heritage policy meets community praxis: Widening conservation approaches in the traditional villages of central Greece. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 81, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Q.; Aimar, F.; Chen, L. The Joint Force of bottom-up and top-down in the Preservation and Renewal of Rural Architectural Heritage—Taking Piedmont, Italy as the Case Study. Architecture 2021, 1, 34–41. [Google Scholar]

- Landorf, C. Managing for Sustainable Tourism: A Review of Six Cultural World Heritage Sites. J. Sustain. Tour. 2009, 17, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, J. ‘Fifty-two doors’: Identifying cultural significance through narrative and nostalgia in Lakhnu village. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2013, 20, 415–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardaro, R.; La Sala, P.; De Pascale, G.; Faccilongo, N. The conservation of cultural heritage in rural areas: Stakeholder preferences regarding historical rural buildings in Apulia, southern Italy. Land Use Policy 2021, 109, 105662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.; Delicado, A. Wind farms and rural tourism: A Portuguese case study of residents’ and visitors’ perceptions and attitudes. Morav. Geogr. Rep. 2017, 25, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakopoulou, S.; Kaliampakos, D. The social aspects of rural, mountainous built environment. Key elements of a regional policy planning. J. Cult. Herit. 2016, 21, 849–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boniotti, C. The public–private–people partnership (P4) for cultural heritage management purposes. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dente, B.O.; Bobbio, L.; Spada, A. Government or Governance of Urban Innovation? disP-Plan. Rev. 2005, 41, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zscheischler, J.; Busse, M.; Heitepriem, N. Challenges to Build up a Collaborative Landscape Management (CLM)—Lessons from a Stakeholder Analysis in Germany. Environ. Manag. 2019, 64, 580–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beckley, T.M.; Martz, D.; Nadeau, S.; Wall, E.; Reimer, B. Multiple capacities, multiple outcomes: Delving deeper into the meaning of community capacity. J. Rural. Community Dev. 2008, 3, 56–75. [Google Scholar]

- Cina’, G.; Demiröz, M.; Mu, Q. Participation and conflict between local community and institutions in conservation processes. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 9, 134–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkoltsiou, A.; Athanasiadou, E.; Paraskevopoulou, A. Agricultural Heritage Landscapes of Greece: Three Case Studies and Strategic Steps towards Their Acknowledgement, Conservation and Management. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekakis, S.; Dragouni, M. Heritage in the making: Rural heritage and its mnemeiosis at Naxos island, Greece. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 77, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcindor, M.; Jackson, D.; Alcindor-Huelva, P. Heritage places and the place attachment of adolescents: The case of the Castelo of Vila Nova de Cerveira (Portugal). J. Rural Stud. 2021, 88, 410–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, T.; Madgin, R. The inherent malleability of heritage: Creating China’s beautiful villages. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2018, 24, 938–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schriver, S. Cultural Heritage Preservation in Regional China: Tourism, Culture and the Shaxi Model. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Western Australia, Perth, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, S.H. Ecomuseum evaluation: Experiences in Guizhou and Guangxi, China. In Proceedings of the 3rd World Planning Schools Congress, WPSC 2011, Perth, Australia, 4–8 July 2011; pp. 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Stojević, I. Village and Heritage in China: A Discussion on the Influence and Future of Heritage Work in Rural Areas. Heritage 2019, 2, 666–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, B. Patronage and Power: Local State Networks and Party-State Resilience in Rural China; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pola, A.-P. When Heritage Is Rural: Environmental Conservation, Cultural Interpretation and Rural Renaissance in Chinese Listed Villages. Built Herit. 2019, 3, 64–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, L.G.; Perez, M.R.; Yang, X. Geriletu from Farm to Rural Hostel: New Opportunities and Challenges Associated with Tourism Expansion in Daxi, a Village in Anji County, Zhejiang, China. Sustainability 2011, 3, 306–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferretto, P.W.; Cai, L. Village prototypes: A survival strategy for Chinese minority rural villages. J. Arch. 2020, 25, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renfer, C. Considerations of a Swiss Monument Preservationist during a Visit to Traditional Villages in China: The Yunnan Shaxi Rehabilitation Project as an Opportunity. Built Herit. 2017, 1, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Tilson, W.L.; Zhu, D. Architectural Features of Stilted Buildings of the Tujia People: A Case Study of Ancient Buildings in the Peng Family Village in Western Hubei Province, China. J. Build. Constr. Plan. Res. 2013, 1, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Yunxia, W.; Prott, L.V. Cultural revitalisation after catastrophe: The Qiang culture in A’er. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2015, 22, 26–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattingly, D.C. The Social Origins of State Power in China. Ph.D. Thesis, University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mattingly, D.C. Elite Capture: How Decentralization and Informal Institutions Weaken Property Rights in China. World Politics 2016, 68, 383–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, M. Lineage Organization in Southeastern China; Routledge: London, UK, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Iossifova, D. Cultural Heritage: Preservation and Development with Chinese Characteristics. Available online: https://www.research.manchester.ac.uk/portal/en/publications/cultural-heritage-preservation-and-development-with-chinese-characteristics(48f7896d-48c2-4de2-803c-4af045ab1e09)/export.html (accessed on 18 May 2022).

- Martínez, P.G. The ‘preservation by relocation’ of Huizhou vernacular architecture: Shifting notions on the authenticity of rural heritage in China. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2021, 28, 200–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.H.; Iankova, K.; Zhang, Y.; McDonald, T.; Qi, X. The role of self-gentrification in sustainable tourism: Indigenous entrepreneurship at Honghe Hani Rice Terraces World Heritage Site, China. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 24, 1262–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, M. Understanding Heritage-Led Development of the Historic Villages of China: A Multi-case Study Analysis of Tongren. Hist. Environ. Policy Pract. 2021, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Li, Q. Poverty alleviation, community participation, and the issue of scale in ethnic tourism in China. Asian Anthr. 2020, 19, 233–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, D. Urban Planning Goes Rural. China Perspect. 2013, 2013, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]