The Role of Housing Tenure Opportunities in the Social Integration of the Aging Pre-1970 Migrants in Beijing

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Social Integration of Aging Migrants in China: Review and Conceptualization

2.1. Migration, Aging, and the Role of the Housing Regime in the Social Stratification and Inclusion

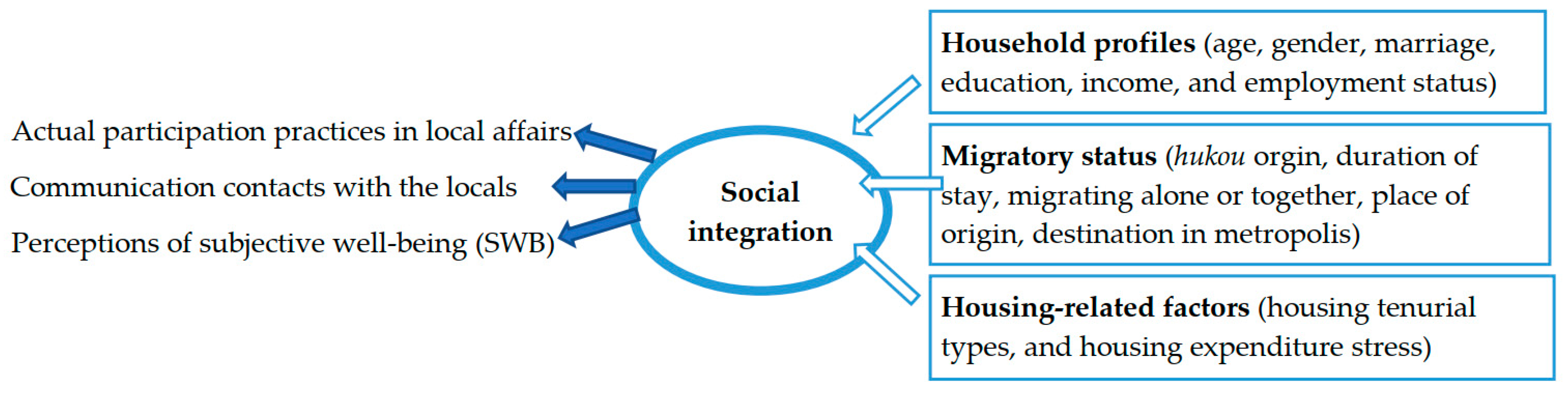

2.2. Conceptualization, Framework, and Hypotheses

- (a)

- Their actual participation in local affairs (regardless of a small group-like community/neighborhood or the mass society of a city);

- (b)

- Communication contacts with the locals, beyond their own patriarchal family- and clan-relationship (namely “laoxiang” as people from similar originating areas); and

- (c)

- Migrants’ relevant perceptions of subjective well-being (SWB).

3. Data and Method

3.1. Research Area and Data Source

3.2. Variable Selection and Methodology

3.3. Regression Model Selection

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistical Analysis

4.2. Regression on the Pre-1970 Migrants’ Integration Status

4.2.1. Explaining the Practical Dimension of Aging Migrants’ Integration

4.2.2. Explaining the Relational Dimension of Aging Migrants’ Integration

4.2.3. Explaining the Perceptual Dimension of Aging Migrants’ Integration

5. Discussion

5.1. Reinterpreting Social Integration in the Chinese Urbanizing Regime

5.2. Main Findings

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Montes de Oca, V.; García, T.R.; Sáenz, R.; Guillén, J. The Linkage of Life Course, Migration, Health, and Aging: Health in Adults and Elderly Mexican Migrants. J. Aging Health 2011, 23, 1116–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristiansen, M.; Razum, O.; Tezcan-Güntekin, H.; Krasnik, A. Aging and health among migrants in a European perspective. Public Health Rev. 2016, 37, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization. Global strategy and action plan on ageing and health 2016–2020: Towards a world in which everyone can live a long and healthy life. In Proceedings of the Sixty-Ninth World Health Assembly, Geneva, Switzerland, 23–29 May 2016. [Google Scholar]

- The WHO Regional Office for Europe. Building healthy cities: Inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable. In Proceedings of the WHO European Healthy Cities Network Annual Business and Technical Conference, Pécs, Hungary, 1–3 March 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Warner, M.; Zhu, Y. The challenges of managing “new generation” employees in contemporary China: Setting the scene. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2018, 24, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Wang, K. China’s New Generation Migrant Workers’ Urban Experience and Well-Being. In Mobility, Sociability and Well-being of Urban Living; Wang, D., He, S., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 67–91. [Google Scholar]

- Amber, D.; Domingo, J. The Discourse on the Unemployment of People over 45 Years Old in Times of Crisis. A Study of Spanish Blogs. J. Aging Soc. Policy 2016, 7, 63–78. [Google Scholar]

- Drydakis, N.; MacDonald, P.; Chiotis, V.; Somers, L. Age Discrimination in the UK Labour Market. Does Race Moderate Ageism? An Experimental Investigation. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2018, 25, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Sun, C.L. Research on Age Discrimination against Job Seekers Based on Recruitment Advertisements. Open Access Libr. J. 2021, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Tao, R. Social capital and migrant housing experiences in urban China: A structural equation modeling analysis. Hous. Stud. 2013, 28, 1155–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, K. Jane Jacobs and “the need for aged buildings”: Neighbourhood historical development pace and community social relations. Urban Stud. 2013, 50, 2407–2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chan, K.W. China’s Hukou System at 60: Continuity and Reform. In Handbook on Urban Development in China; Yep, R., Wang, J., Johnson, T., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2019; pp. 59–79. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, H. Understanding the migration of highly and less-educated labourers in post-reform China. Appl. Geogr. 2021, 137, 102605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State Council. Opinion on Further Reform of the Hukou System. Beijing; 30 July 2014. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2014-07/30/content_8944.htm (accessed on 12 April 2022). (In Chinese)

- NDRC (National Development and Reform Commission). Memo on Promoting Experiences Based on the Third Group of Comprehensive Pilot Cities in New-Type of Urbanization. 26 August 2021. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2021-08/31/content_5634330.htm (accessed on 12 April 2022). (In Chinese)

- Li, Y.; Xiong, C.; Zhu, Z.; Lin, Q. Family Migration and Social Integration of Migrants: Evidence from Wuhan Metropolitan Area, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Z.; Li, S.; Jin, X.; Feldman, M. The Role of Social Networks in the Integration of Chinese Rural-Urban Migrants: A Migrant-Resident Tie Perspective. Urban Stud. 2013, 50, 1704–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zou, J.; Chen, Y.; Chen, J. The complex relationship between neighbourhood types and migrants’ socio-economic integration: The case of urban China. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2020, 35, 65–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Zhang, F.; Wu, F. Contrasting migrants’ sense of belonging to the city in selected peri-urban neighbourhoods in Beijing. Cities 2022, 120, 103499. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, S.; Wu, F.; Li, Z. Social integration of migrants across Chinese neighbourhoods. Geoforum 2020, 112, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, J.R.; Spitze, G.D. Family Neighbors. Am. J. Sociol. 2002, 100, 453–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, K.E.; Lee, B.A. Sources of Personal Neighbor Networks: Social Integration, Need, or Time? Soc. Forces 1992, 70, 1077–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kweon, B.S.; Sullivan, W.C.; Wiley, A.R. Green Common Spaces and the Social Integration of Inner-City Older Adults. Environ. Behav. 1998, 30, 832–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Huang, Y. Community environmental satisfaction: Its forms and impact on migrants’ happiness in urban China. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2018, 16, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tang, S.; Lee, H.; Feng, J. Social capital, built environment and mental health: A comparison between the local elderly people and the “laopiao” in urban China. Ageing Soc. 2020, 42, 179–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Chen, S.; Wang, P. Language barriers and health status of elderly migrants: Micro-evidence from China. China Econ. Rev. 2019, 54, 94–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Rosenberg, M.; Winterton, R.; Blackberry, I.; Gao, S. Mobilities of Older Chinese Rural-Urban Migrants: A Case Study in Beijing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, Y.; Dijst, M.; Faber, J.; Geertman, S.; Cui, C. Healthy urban living: Residential environment and health of older adults in Shanghai. Health Place 2017, 47, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Tang, S.; Chuai, X. The impact of neighbourhood environments on quality of life of elderly people: Evidence from Nanjing, China. Urban Stud. 2018, 55, 2020–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Gao, X.; Lyon, M. Modeling satisfaction amongst the elderly in different Chinese urban neighborhoods. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014, 118, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, C.; Liu, Y.; Liu, S. On the Settlement of the Floating Population in the Pearl River Delta: Understanding the Factors of Permanent Settlement Intention versus Housing Purchase Actions. Nat. Sustain. 2020, 12, 9771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Guo, F. Breaking the barriers: How urban housing ownership has changed migrants’ settlement intentions in China. Urban Stud. 2018, 55, 3689–3707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Zhang, C. City size and housing purchase intention: Evidence from rural–urban migrants in China. Urban Stud. 2020, 57, 1866–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Ning, Y. The Social Integration of Migrants in Shanghai’s Urban Villages. China Rev. 2016, 16, 93–120. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Chen, J.; Bian, Z.; Wang, H.; Wang, Z. Housing, Housing Stratification, and Chinese Urban Residents’ Social Satisfaction: Evidence from a National Household Survey. Soc. Indic. Res. 2020, 152, 653–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rex, J. The Concept of Housing Class and the Sociology of Race Relations. Race Cl. 1971, 12, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Song, Z.; Sun, W. Do affordable housing programs facilitate migrants’ social integration in Chinese cities? Cities 2020, 96, 102449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Yu, X.; Zhang, J. Urban village demolition, migrant workers’ rental costs and housing choices: Evidence from Hangzhou, China. Cities 2019, 94, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Chen, J. Beyond homeownership: Housing conditions, housing support and rural migrant urban settlement intentions in China. Cities 2018, 78, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manturuk, K.; Lindblad, M.; Quercia, R. Friends and Neighbors: Homeownership and Social Capital among Low- To Moderate-Income Families. J. Urban Aff. 2010, 32, 471–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, N.K. Local house prices and mental health. Int. J. Health Econ. Manag. 2016, 16, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, G.R.; Jung, Y. Housing insecurity and health among people in South Korea: Focusing on tenure and affordability. Public Health 2019, 171, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Fan, C. China’s Hukou puzzle: Why don’t rural migrants want urban Hukou? China Rev. 2016, 16, 9–39. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Wang, W. Economic incentives and settlement intentions of rural migrants: Evidence from China. J. Urban Aff. 2019, 41, 372–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fanelli, A. Extensiveness of Communication Contacts and Perceptions of the Community. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1956, 21, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R. Explanation in Social Science; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gracia, E.; Herrero, J. Determinants of social integration in the community: An exploratory analysis of personal, interpersonal and situational variables. J. Community Appl. Soc. 2004, 14, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lewicka, M. What makes neighborhood different from home and city? Effects of place scale on place attachment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinhans, R. Social implications of housing diversification in urban renewal: A review of recent literature. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2004, 19, 367–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, L.; Arbaci, S. The Challenges of Understanding Urban Segregation. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2011, 37, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galster, G.; Andersson, R.; Musterd, S. Who is affected by neighbourhood income mix? Gender, age, family, employment and income differences. Urban Stud. 2010, 47, 2915–2944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ager, A.; Strang, A. Understanding Integration: A Conceptual Framework. J. Refug. Stud. 2008, 21, 166–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Castles, S.; Korac, M.; Vasta, E.; Vertovec, S. Integration: Mapping the Field; Report of a project carried out by the Centre for Migration and Policy Research and Refugee Studies Centre for the Home Office; University of Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, J. Social integration of new-generation migrants in Shanghai China. Habitat Int. 2015, 49, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Tao, R. Housing migrants in Chinese cities: Current status and policy design. Environ. Plan. C 2015, 33, 640–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, R.; Wong, T.C.; Liu, S. Peasants’ counterplots against the state monopoly of the rural urbanization process: Urban villages and “small property housing” in Beijing, China. Environ. Plan. A 2012, 44, 1219–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W. Sources of Migrant Housing Disadvantage in Urban China. Environ. Plan. A 2004, 36, 1285–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, Y.; Yi, C. Invisible migrant enclaves in Chinese cities: Underground living in Beijing, China. Urban Stud. 2015, 52, 2948–2973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Rosenberg, M.W. Aging and the changing urban environment: The relationship between older people and the living environment in post-reform Beijing, China. Urban Geogr. 2019, 41, 162–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, R.; Wong, T.C. Urban village redevelopment in Beijing: The state-dominated formalization of informal housing. Cities 2018, 72, 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, R.E.; Burgess, E.W. Introduction to the Science of Sociology; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1921. [Google Scholar]

- Keyes, C. Social Well-Being. Soc. Psychol. Q. 1998, 61, 121–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, C. To Dwell among Friends; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Dorvil, H.; Morin, P.; Beaulieu, A.; Robert, D. Housing as a social integration factor for people classified as mentally ill. Hous. Stud. 2005, 20, 497–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keene, D.; Bader, M.; Ailshire, J. Length of residence and social integration: The contingent effects of neighborhood poverty. Health Place 2013, 21, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Adams, R.E.; Serpe, R.T. Social Integration, Fear of Crime, and Life Satisfaction. Sociol. Perspect. 2000, 43, 605–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musterd, S.; Ostendorf, W. Residential segregation and integration in the Netherlands. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2009, 35, 1515–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, S. Social Integration in Post-Multiculturalism: An Analysis of Social Integration Policy in Post-war Britain. Int. J. Jpn. Sociol. 2011, 20, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Wu, F.; Li, Z. Beyond neighbouring: Migrants’ place attachment to their host cities in China. Popul. Space Place 2021, 27, e2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Zhou, C.; Jin, W. Integration of migrant workers: Differentiation among three rural migrant enclaves in Shenzhen. Cities 2020, 96, 102453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; He, S. Informal Property Rights as Relational and Functional: Unravelling the Relational Contract in China’s Informal Housing Market. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2020, 44, 967–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlay, J.M.; Finn, B.M. Geography’s blind spot: The age-old urban question. Urban Geogr. 2021, 42, 1061–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Indicators | Descriptions | Mean | Standard Deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variables | ||||

| No = 0, Yes = 1 | 0.44 | 0.49 | |

| No = 0, Yes = 1 | 0.26 | 0.44 | |

| No = 0, Yes = 1 | 0.19 | 0.39 | |

| Explanatory variables | ||||

| Age (years old) | Continuous variable | 57.74 | 8.25 |

| Gender | Male = 1, Female = 2 | 1.43 | 0.50 | |

| Marital status | Married = 1, Unmarried = 2 | 1.10 | 0.30 | |

| Educational attainment | Primary and below = 1, Junior secondary = 2, Senior/technical secondary = 3, College and above = 4 | 2.22 | 0.96 | |

| Household monthly income (logged, unit: yuan) | Continuous variable | 3.85 | 0.33 | |

| Employment status | Employed = 1, Unemployed or retired = 2 | 1.41 | 0.49 | |

| Hukou origin | Rural hukou = 1, Urban hukou = 2 | 1.42 | 0.49 |

| Duration of stay in Beijing (years) | Continuous variable | 9.73 | 7.73 | |

| Migrate alone or together | Yes (migrate alone) = 1, No (migrate together with family) = 2 | 1.96 | 0.21 | |

| Place of origin | Eastern Region = 1, North Region = 2, Central Region = 3, South-Western Region = 4, North-Western Region = 5, North-Eastern Region = 6 | 3.18 | 2.22 | |

| Destination in Beijing metropolis | Core District of Capital Function = 1, Urban Function Extended Districts = 2, New Districts of Urban Development = 3, Ecological Reserve Development Areas = 4 | 2.24 | 0.77 | |

| Housing tenure types | Self-owned commercial housing = 1, Dormitory-like housing provided by governments or employer units = 2, Rental commercial housing = 3, Informal housing = 4 | 2.55 | 1.20 |

| Housing stress (housing expenditure-to-income ratio) | Continuous variable | 0.14 | 0.39 |

| Self-Owned Commercial Housing | Dormitory-Like Housing Provided by Governments or Employer Units | Rental Commercial Housing | Informal Housing | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sampling | 382 | 30.1% | 186 | 14.7% | 321 | 25.3% | 378 | 29.8% | 1267 | 100% | |

| Dependent variables | |||||||||||

| Yes | 208 | 54.5% | 88 | 47.3% | 145 | 45.2% | 122 | 32.3% | 563 | 44.4% |

| No | 174 | 45.5% | 98 | 52.7% | 176 | 54.8% | 256 | 67.7% | 704 | 55.6% | |

| Yes | 155 | 40.6% | 34 | 18.3% | 67 | 20.9% | 70 | 18.5% | 326 | 25.7% |

| No | 227 | 59.4% | 152 | 81.7% | 254 | 79.1% | 308 | 81.5% | 941 | 74.3% | |

| Yes | 116 | 30.4% | 20 | 10.8% | 49 | 15.3% | 57 | 15.1% | 242 | 19.1% |

| No | 266 | 69.6% | 166 | 89.2% | 272 | 84.7% | 321 | 84.9% | 1025 | 80.9% | |

| Explanatory variables | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Gender | Male | 181 | 47.4% | 124 | 66.7% | 179 | 55.8% | 237 | 62.7% | 721 | 56.9% |

| Female | 201 | 52.6% | 62 | 33.3% | 142 | 44.2% | 141 | 37.3% | 546 | 43.1% | |

| Marital Status | Single | 39 | 10.2% | 27 | 14.5% | 23 | 7.2% | 36 | 9.5% | 125 | 9.9% |

| Married | 343 | 89.8% | 159 | 85.5% | 298 | 92.8% | 342 | 90.5% | 1142 | 90.1% | |

| Education | Primary and below | 54 | 14.1% | 51 | 27.4% | 85 | 26.5% | 132 | 34.9% | 322 | 25.4% |

| Junior secondary | 103 | 27.0% | 82 | 44.1% | 139 | 43.3% | 166 | 43.9% | 490 | 38.7% | |

| Senior/technical secondary | 127 | 33.2% | 48 | 25.8% | 67 | 20.9% | 65 | 17.2% | 307 | 24.2% | |

| College and above | 98 | 25.7% | 5 | 2.7% | 30 | 9.3% | 15 | 4.0% | 148 | 11.7% | |

| Employment status | Employed | 61 | 16.0% | 164 | 88.2% | 237 | 73.8% | 283 | 74.9% | 745 | 58.8% |

| Unemployed or retired | 321 | 84.0% | 22 | 11.8% | 84 | 26.2% | 95 | 25.1% | 522 | 41.2% | |

| |||||||||||

| Hukou origin | Rural hukou | 82 | 21.5% | 144 | 77.4% | 217 | 67.6% | 294 | 77.8% | 737 | 58.2% |

| Urban hukou | 300 | 78.5% | 42 | 22.6% | 104 | 32.4% | 84 | 22.2% | 530 | 41.8% | |

| Migrate alone or not | Migrate alone | 10 | 2.6% | 19 | 10.2% | 13 | 4.0% | 15 | 4.0% | 57 | 4.5% |

| Migrate together with family | 372 | 97.4% | 167 | 89.8% | 308 | 96.0% | 363 | 96.0% | 1210 | 95.5% | |

| Place of origin | Eastern Region | 77 | 20.2% | 41 | 22.0% | 80 | 24.9% | 85 | 22.5% | 283 | 22.3% |

| North Region | 121 | 31.7% | 66 | 35.5% | 84 | 26.2% | 120 | 31.7% | 391 | 30.9% | |

| Central Region | 53 | 13.9% | 36 | 19.4% | 82 | 25.5% | 73 | 19.3% | 244 | 19.3% | |

| South-Western Region | 19 | 5.0% | 10 | 5.4% | 23 | 7.2% | 29 | 7.7% | 81 | 6.4% | |

| North-Western Region | 26 | 6.8% | 8 | 4.3% | 13 | 4.0% | 4 | 1.1% | 51 | 4.0% | |

| North-Eastern Region | 86 | 22.4% | 25 | 13.4% | 39 | 12.2% | 67 | 17.7% | 217 | 17.1% | |

| Destination in Beijing metropolis | Core District of Capital Function | 38 | 9.9% | 34 | 18.3% | 58 | 18.1% | 34 | 9.0% | 164 | 12.9% |

| Urban Function Extended Districts | 256 | 67.0% | 112 | 60.2% | 220 | 68.5% | 143 | 37.8% | 731 | 57.7% | |

| New Districts of Urban Development | 57 | 14.9% | 29 | 15.6% | 28 | 8.7% | 166 | 43.9% | 280 | 22.1% | |

| Ecological Reserve Development Areas | 31 | 8.1% | 11 | 5.9% | 15 | 4.7% | 35 | 9.3% | 92 | 7.3% | |

| All Pre-1970 Migrants in Beijing | ≥60 Years Old | <60 Years Old & Pre-1970 | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Local Affairs Participation | 2. Communication with Locals as the Most Frequent Contacts | 3. Full Integration Perceived (SWB) | 1. Local Affairs Participation | 2. Communication with Locals as the Most Frequent Contacts | 3. Full Integration Perceived (SWB) | 1. Local Affairs Participation | 2. Communication with Locals as the Most Frequent Contacts | 3. Full Integration Perceived (SWB) | ||||||||||

| Predictors | Β | Exp(β) | Β | Exp(β) | Β | Exp(β) | Β | Exp(β) | Β | Exp(β) | Β | Exp(β) | Β | Exp(β) | Β | Exp(β) | Β | Exp(β) |

| Household profile | ||||||||||||||||||

| Age (years old) | −0.024 ** | 0.976 | −0.001 | 0.999 | 0.008 | 1.008 | −0.060 ** | 0.942 | −0.018 | 0.982 | 0.029 | 1.030 | −0.096 *** | 0.908 | −0.081 ** | 0.923 | 0.042 | 1.043 |

| Gender (ref = female) | 0.016 | 1.016 | −0.276 * | 0.759 | −0.048 | 0.953 | 0.051 | 1.052 | −0.308 | 0.735 | −0.511 ** | 0.600 | 0.101 | 1.106 | −0.290 | 0.748 | 0.173 | 1.189 |

| Marriage (ref = unmarried) | −0.276 | 0.759 | −0.035 | 0.966 | 0.092 | 1.096 | −0.303 | 0.739 | 0.254 | 1.277 | 0.731 | 2.078 | −0.398 | 0.672 | −0.821 * | 0.440 | −0.667 | 0.513 |

| Education level (ref = college and higher) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Primary and below | −1.382 *** | 0.251 | −0.714 ** | 0.490 | −0.338 | 0.713 | −1.441 *** | 0.237 | −0.654 | 0.524 | 0.111 | 1.117 | −1.089 ** | 0.337 | −0.995 ** | 0.370 | −0.978 * | 0.376 |

| Junior secondary | −1.002 *** | 0.367 | −0.326 | 0.722 | −0.218 | 0.804 | −1.182*** | 0.307 | 0.188 | 1.207 | 0.113 | 1.119 | −0.649 * | 0.523 | −0.770 * | 0.463 | −0.868 * | 0.420 |

| Senior/technical secondary | −0.42 * | 0.657 | −0.172 | 0.842 | 0.300 | 1.349 | −0.691** | 0.501 | −0.096 | 0.908 | 0.368 | 1.445 | 0.102 | 1.107 | −0.224 | 0.799 | −0.137 | 0.872 |

| Logged familial income (annual, unit: yuan) | −0.494 ** | 0.610 | −0.190 | 0.827 | −0.228 | 0.796 | −0.653 ** | 0.520 | −0.246 | 0.782 | 0.100 | 1.105 | −0.084 | 0.919 | 0.095 | 1.100 | −0.753 * | 0.471 |

| Employment status (ref = retired/unemployed) | 0.329 * | 1.390 | −0.228 | 0.796 | −0.555 ** | 0.574 | 0.227 | 1.255 | 0.073 | 1.076 | −1.864 ** | 0.155 | −0.087 | 0.917 | −0.054 | 0.947 | 0.123 | 1.131 |

| Migratory status | ||||||||||||||||||

| Hukou origin (ref = urban hukou) | −0.227 | 0.797 | −0.512 ** | 0.599 | 0.118 | 1.125 | −0.265 | 0.767 | −0.476 | 0.621 | 0.012 | 1.012 | −0.212 | 0.809 | −0.523** | 0.588 | 0.324 | 1.383 |

| Duration of stay in Beijing (years) | 0.042 *** | 1.043 | 0.039 *** | 1.040 | 0.043 *** | 1.044 | 0.059 ** | 1.061 | 0.037 ** | 1.037 | 0.056 ** | 1.058 | 0.040 *** | 1.041 | 0.043 *** | 1.044 | 0.036 ** | 1.037 |

| Migrate alone or together (ref = with family) | 0.131 | 1.140 | −0.361 | 0.697 | 0.383 | 1.467 | 0.390 | 1.477 | −0.751 | 0.472 | 1.113 | 3.044 | 0.045 | 1.046 | −0.699 | 0.497 | −0.565 | 0.568 |

| Place of origin (ref = North−Eastern China) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Eastern Region | −0.079 | 0.924 | −0.066 | 0.936 | −0.165 | 0.848 | −0.316 | 0.729 | −0.042 | 0.959 | −0.679 * | 0.507 | 0.101 | 1.106 | 0.058 | 1.060 | 0.147 | 1.158 |

| North China | −0.013 | 0.987 | 0.215 | 1.240 | −0.251 | 0.778 | −0.039 | 0.962 | 0.038 | 1.038 | −0.377 | 0.686 | −0.021 | 0.979 | 0.375 | 1.455 | −0.201 | 0.818 |

| Central China | −0.001 | 0.999 | 0.002 | 0.995 | −0.040 | 0.961 | −0.311 | 0.733 | −0.066 | 0.936 | −0.063 | 0.939 | 0.129 | 1.137 | 0.183 | 1.210 | 0.150 | 1.162 |

| South−Western Region | −0.130 | 0.874 | −0.917 ** | 0.400 | −0.051 | 0.951 | −0.502 | 0.605 | −0.150 | 0.860 | −0.821 | 0.440 | −0.026 | 0.974 | −1.751 ** | 0.174 | 0.389 | 1.475 |

| North−Western Region | −0.032 | 0.969 | 0.660 * | 1.936 | 0.523 | 1.687 | 0.201 | 1.222 | 0.903 * | 2.468 | 0.740 | 2.095 | −0.241 | 0.786 | −0.020 | 0.981 | −0.056 | 0.946 |

| Destination in Beijing metropolis (ref = Ecological Reserve Development Areas) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Core District of Capital Function | 0.328 | 1.388 | −0.891 ** | 0.410 | −0.377 | 0.686 | 0.349 | 1.417 | −2.109 *** | 0.121 | 0.163 | 1.177 | 0.431 | 1.539 | −0.520 | 0.595 | −0.615 | 0.541 |

| Urban Function Extended Districts | 0.406 | 1.501 | −1.112 *** | 0.329 | −0.487 * | 0.614 | 0.796 * | 2.216 | −2.320 *** | 0.098 | −0.078 | 0.925 | 0.238 | 1.268 | −0.659 * | 0.517 | −0.434 | 0.648 |

| New Districts of Urban Development | 0.304 | 1.355 | −0.709 ** | 0.492 | 0.106 | 1.112 | 0.792 | 2.208 | −1.844 ** | 0.158 | 0.895 | 2.448 | 0.079 | 1.082 | −0.248 | 0.780 | −0.043 | 0.958 |

| Housing−related factors | ||||||||||||||||||

| Housing tenure types (ref = Informal housing) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Self−owned commercial housing | 0.971 *** | 2.641 | 0.647 ** | 1.909 | 0.654 ** | 1.923 | 1.204 ** | 2.784 | 0.504 | 1.656 | 0.393 | 1.482 | 0.387 | 1.472 | 0.574 * | 1.776 | 1.056 ** | 2.876 |

| Dormitory−like from gov or employer units | 0.475 ** | 1.607 | 0.142 | 1.153 | −0.191 | 0.826 | −0.002 | 0.998 | 0.797 * | 2.219 | 0.146 | 1.158 | 0.697 ** | 2.008 | −0.175 | 0.839 | −0.428 | 0.652 |

| Rental commercial housing | 0.498 ** | 1.645 | 0.117 | 1.125 | 0.126 | 1.134 | 0.477 | 1.611 | −0.145 | 0.865 | 0.083 | 1.086 | 0.401 * | 1.493 | 0.121 | 1.128 | 0.183 | 1.201 |

| Housing stress (expenditure−to−income ratio) | −0.214 | 0.807 | 0.212 | 1.237 | 0.219 | 1.244 | −0.373 | 0.689 | 0.148 | 1.159 | 0.401 | 1.493 | 0.331 | 1.392 | 0.398 | 1.490 | −0.479 | 0.619 |

| Constant | 2.857 ** | 17.415 | 0.800 | 2.226 | −1.154 | 0.316 | 5.856 ** | 349.257 | 3.059 | 22.095 | −4.642 ** | 0.010 | 5.088 ** | 162.008 | 4.089 * | 59.675 | −0.409 | 0.664 |

| N | 1267 | 1259 | 1267 | 495 | 495 | 495 | 772 | 772 | 772 | |||||||||

| df | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 | |||||||||

| λ2 | 152.633 | 141.969 | 95.174 | 83.028 | 65.398 | 68.257 | 96.555 | 92.361 | 45.571 | |||||||||

| −2 Log−Likelihood | 1577.344 | 1285.410 | 1131.423 | 590.522 | 564.252 | 476.144 | 959.008 | 670.304 | 621.15 | |||||||||

| Nagelkerke R2 | 0.153 | 0.157 | 0.117 | 0.209 | 0.173 | 0.194 | 0.158 | 0.180 | 0.099 | |||||||||

| Percent correctly classified | 66.2% | 76.2% | 81.7% | 67.2% | 71.3% | 75.4% | 67.4% | 81.1% | 84.7% | |||||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhu, Y.; Cao, W.; Li, X.; Liu, R. The Role of Housing Tenure Opportunities in the Social Integration of the Aging Pre-1970 Migrants in Beijing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7093. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19127093

Zhu Y, Cao W, Li X, Liu R. The Role of Housing Tenure Opportunities in the Social Integration of the Aging Pre-1970 Migrants in Beijing. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(12):7093. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19127093

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhu, Ye, Weiyu Cao, Xin Li, and Ran Liu. 2022. "The Role of Housing Tenure Opportunities in the Social Integration of the Aging Pre-1970 Migrants in Beijing" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 12: 7093. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19127093

APA StyleZhu, Y., Cao, W., Li, X., & Liu, R. (2022). The Role of Housing Tenure Opportunities in the Social Integration of the Aging Pre-1970 Migrants in Beijing. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(12), 7093. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19127093