Document de Consensus Sur la Prise en Charge du Cholestérol LDL

Abstract

- −

- Les taux plasmatiques de c-LDL sont particulièrement élevés chez l’homme adulte, contrairement à la plupart des espèces animales

- −

- L’athérosclérose est typiquement une maladie humaine, et elle est très fréquente

- −

- Les taux de c-LDL sont principalement liés à la qualité et quantité de l’alimentation, ainsi que la sédentarité et la tabagisme

- −

- Les taux de c-LDL sont parfois déterminés génétiquement et augmentent avec l’âge

- −

- Le taux de c-LDL est directement associé au développement des plaques d’athérosclérose

- −

- Les plaques athérosclérose sont responsables de la majorité des infarctus du myocarde et des AVC, et ainsi d’une grande partie des décès cardiovasculaires

- −

- Les mutations génétiques associées à des taux sanguins de c-LDL abaissé protègent contre la survenue d'infarctus du myocarde et de la mort subite, alors que celles associées à des taux élevés de c-LDL peuvent provoquer les pathologies liées à l’athérosclérose déjà mentionnées

- −

- Différentes thérapies médicamenteuses permettent de réduire les taux plasmatiques de c-LDL

- −

- Les principaux médicaments hypolipémiants sont les statines, l’ézétimibe et les inhibiteurs de la protéine PCSK9

- −

- Ces traitements hypolipémiants réduisent considérablement le risque d’infarctus du myocarde, d’AVC et de morts subites

- −

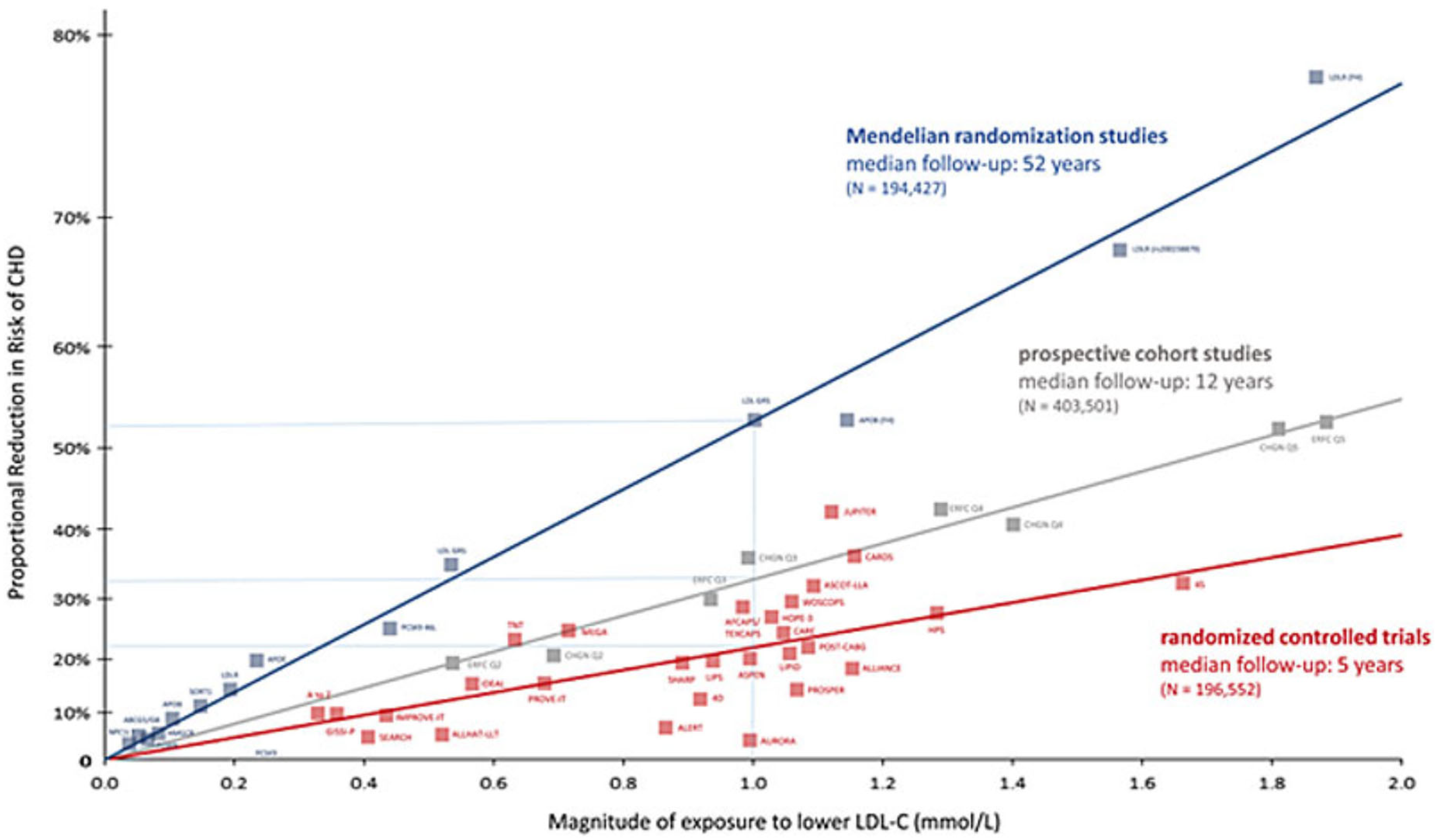

- Plus le taux de c-LDL est bas, plus le risque de crise cardiaque, d'AVC et risque de mort subite est faible (le plus bas, le mieux «the lower, the better»)

- −

- Le risque cardiovasculaire de développer un infarctus du myocarde, un AVC ou une mort subit détermine l'utilisation de traitements hypolipémiant ainsi que leurs posologie.

- −

- Les patients qui ont présenté un événement clinique lié à des lésions d’athérosclérose, ou chez qui des lésions d’athérosclérose ont été mises en évidence (principalement par l’imagerie) sont à risque très élevé de récurrence d'événements cardiaques

- −

- Pour les patients à haut et à très haut risque, la valeur cible du c-LDL doit être <1,8 ou <1,4 mmol/L, ainsi qu’un abaissement de 50% des valeurs mesurées sans traitement.

Cholestérol et athérosclérose

Athérosclérose et événements cardiovasculaires cliniques

Génétique et métabolisme du cholestérol

Baisse du cholestérol et réduction de la morbimortalité cardiovasculaire

Qu’est-ce qu’un taux de LDL-cholestérol normal?

Traitements hypolipémiants

Evaluation du risque cardiovasculaire

Valeurs cibles des lipides plasmatiques

Directives de l’Office fédéral de la santé publique

- −

- les patients adultes avec hypercholestérolémie,

- −

- les patients adultes avec hypercholestérolémie familiale hétérozygote,

- −

- les patients adultes et adolescents à partir de 12 ans avec hypercholestérolémie familiale homozygote.

- −

- patients adultes avec hypercholestérolémie familiale hétérozygote sévère présentant une valeur de c-LDL >5.0 mmol/l,

- −

- patients adultes et adolescents à partir de 12 ans avec hypercholestérolémie familiale homozygote présentant une valeur de c-LDL >5.0 mmol/l,

- −

- patients adultes avec hypercholestérolémie familiale hétérozygote sévère présentant une valeur de c-LDL >4.5 mmol/l et au moins l’un des facteurs de risque additionnels suivants: diabète sucré, valeur de lipoprotéine (a) >50 mg/dl (respectivement 120 nmol/L), hypertension artérielle fortement élevée.

- −

- lorsqu’à l’issue d’une thérapie intensive d’au moins 3 mois à la dose maximale tolérée visant à réduire le cLDL et comportant au moins deux statines différentes avec ou sans ézétimibe (ou ézétimibe avec ou sans autre médicament hypolipémiant en cas d’intolérance aux statines) les valeurs de c-LDL ci-dessus n’ont pu être atteintes et

- −

- lorsque la pression artérielle est contrôlée et lorsque le contrôle de la glycémie avec un taux d’HbA1c inférieur à 8% et une abstinence à la nicotine sont recherchés.

- −

- une tentative de traitement avec plusieurs statines a conduit à des myalgies, ou

- −

- à une augmentation de la créatine kinase d’au moins 5 fois la valeur normale supérieure, ou

- −

- une hépatopathie sévère est survenue sous traitement avec une statine.

Disclosure statement

References

- Osler, W. Lectures on Angina Pectoris and Allied States; D. Appleton: New York, NY, USA, 1897. [Google Scholar]

- Anitschkow, N.N. A history of experimentation on arterial atherosclerosis in animals. Cowdry’s Arteriosclerosis: A Survey of the Problem; Charles C Thomas: Springfield, IL, USA, 1967; pp. 21–44. [Google Scholar]

- Akhmedov, A.; Rozenberg, I.; Paneni, F.; Camici, G.G.; Shi, Y.; Doerries, C.; et al. Endothelial overexpression of LOX-1 increases plaque formation and promotes atherosclerosis in vivo. Eur Heart J. 2014, 35, 2839–2848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libby, P.; Lichtman, A.H.; Hansson, G.K. Immune effector mechanisms implicated in atherosclerosis: From mice to humans. Immunity 2013, 38, 1092–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, F.C.; Noll, G.; Boulanger, C.M.; Lüscher, T.F. Oxidized low density lipoproteins inhibit relaxations of porcine coronary arteries. Role of scavenger receptor and endothelium-derived nitric oxide. Circulation 1991, 83, 2012–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gresham, G.A.; Howard, A.N.; McQueen, J.; Bowyer, D.E. Atherosclerosis in primates. Br J Exp Pathol. 1965, 46, 94–103. [Google Scholar]

- Boulanger, C.M.; Tanner, F.C.; Béa, M.L.; Hahn, A.W.; Werner, A.; Lüscher, T.F. Oxidized low density lipoproteins induce mRNA expression and release of endothelin from human and porcine endothelium. Circ Res. 1992, 70, 1191–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libby, P.; Ridker, P.M.; Maseri, A. Inflammation and atherosclerosis. Circulation 2002, 105, 1135–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, C.W.; Preis, S.R.; Peloso, G.M.; Hwang, S.J.; Kathiresan, S.; Fox, C.S.; et al. Relations of long-term and contemporary lipid levels and lipid genetic risk scores with coronary artery calcium in the framingham heart study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012, 60, 2364–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assmann, G.; Cullen, P.; Schulte, H. Simple scoring scheme for calculating the risk of acute coronary events based on the 10-year follow-up of the prospective cardiovascular Münster (PROCAM) study. Circulation. 2002, 105, 310–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Angelantonio, E.; Gao, P.; Pennells, L.; Kaptoge, S.; Caslake, M.; Thompson, A.; et al.; Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration Lipid-related markers and cardiovascular disease prediction. JAMA. 2012, 307, 2499–2506. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lewington, S.; Whitlock, G.; Clarke, R.; Sherliker, P.; Emberson, J.; Halsey, J.; et al. , Prospective Studies Collaboration. Blood cholesterol and vascular mortality by age, sex, and blood pressure: A meta-analysis of individual data from 61 prospective studies with 55,000 vascular deaths. Lancet. 2007, 370, 1829–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, M.S.; Goldstein, J.L. A receptor-mediated pathway for cholesterol homeostasis. Science. 1986, 232, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willer, C.J.; Schmidt, E.M.; Sengupta, S.; Peloso, G.M.; Gustafsson, S.; Kanoni, S.; et al. , Global Lipids Genetics Consortium. Discovery and refinement of loci associated with lipid levels. Nat Genet. 2013, 45, 1274–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.C.; Boerwinkle, E.; Mosley, T.H., Jr.; Hobbs, H.H. Sequence variations in PCSK9, low LDL, and protection against coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2006, 354, 1264–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, P.N.; Defesche, J.; Fouchier, S.W.; Bruckert, E.; Luc, G.; Cariou, B.; et al. Characterization of Autosomal Dominant Hypercholesterolemia Caused by PCSK9 Gain of Function Mutations and Its Specific Treatment With Alirocumab, a PCSK9 Monoclonal Antibody. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2015, 8, 823–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobbs, H.H.; Brown, M.S.; Russell, D.W.; Davignon, J.; Goldstein, J.L. Deletion in the gene for the low-density-lipoprotein receptor in a majority of French Canadians with familial hypercholesterolemia. N Engl J Med. 1987, 317, 734–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mabuchi, H.; Koizumi, J.; Shimizu, M.; Kajinami, K.; Miyamoto, S.; Ueda, K.; et al.; Hokuriku-FH-LDL-Apheresis Study Group Long-term efficacy of low-density lipoprotein apheresis on coronary heart disease in familial hypercholesterolemia. Am J Cardiol. 1998, 82, 1489–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, A. A gift from nature: The birth of the statins. Nat Med. 2008, 14, 1050–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: The Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S). Lancet. 1994, 344, 1383–1389.

- Mihaylova, B.; Emberson, J.; Blackwell, L.; Keech, A.; Simes, J.; Barnes, E.H.; et al. , Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaborators. The effects of lowering LDL cholesterol with statin therapy in people at low risk of vascular disease: Meta-analysis of individual data from 27 randomised trials. Lancet. 2012, 380, 581–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaRosa, J.C.; Grundy, S.M.; Waters, D.D.; Shear, C.; Barter, P.; Fruchart, J.C.; et al.; Treating to New Targets (TNT) Investigators Intensive lipid lowering with atorvastatin in patients with stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2005, 352, 1425–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannon, C.P.; Blazing, M.A.; Giugliano, R.P.; McCagg, A.; White, J.A.; Theroux, P.; et al.; IMPROVE-IT Investigators Ezetimibe Added to Statin Therapy after Acute Coronary Syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2015, 372, 2387–2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatine, M.S.; Giugliano, R.P.; Keech, A.C.; Honarpour, N.; Wiviott, S.D.; Murphy, S.A.; et al.; FOURIER Steering Committee and Investigators Evolocumab and clinical outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2017, 376, 1713–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giugliano, R.P.; Mach, F.; Zavitz, K.; Kurtz, C.; Im, K.; Kanevsky, E.; et al.; EBBINGHAUS Investigators Cognitive Function in a Randomized Trial of Evolocumab. N Engl J Med. 2017, 377, 633–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridker, P.M.; Revkin, J.; Amarenco, P.; Brunell, R.; Curto, M.; Civeira, F.; et al.; SPIRE Cardiovascular Outcome Investigators Cardiovascular Efficacy and Safety of Bococizumab in High-Risk Patients. N Engl J Med. 2017, 376, 1527–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ference, B.A.; Cannon, C.P.; Landmesser, U.; Lüscher, T.F.; Catapano, A.L.; Ray, K.K. Reduction of low density lipoprotein-cholesterol and cardiovascular events with proprotein convertase subtilisin-kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors and statins: An analysis of FOURIER, SPIRE, and the Cholesterol Treatment Trialists Collaboration. Eur Heart J. 2018, 39, 2540–2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, G.G.; Steg, P.G.; Szarek, M.; Bhatt, D.L.; Bittner, V.A.; Diaz, R.; et al. ODYSSEY OUTCOMES Committees and Investigators. Alirocumab and Cardiovascular Outcomes after Acute Coronary Syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2018, 379, 2097–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donegá, S.; Oba, J.; Maranhão, R.C. Concentration of serum lipids and apolipoprotein B in newborns. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2006, 86, 419–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.C.; Allam, A.H.; Lombardi, G.P.; Wann, L.S.; Sutherland, M.L.; Sutherland, J.D.; et al. Atherosclerosis across 4000 years of human history: The Horus study of four ancient populations. Lancet. 2013, 381, 1211–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, R.; Reith, C.; Emberson, J.; Armitage, J.; Baigent, C.; Blackwell, L.; et al. Interpretation of the evidence for the efficacy and safety of statin therapy. Lancet. 2016, 388, 2532–2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ference, B.A.; Ginsberg, H.N.; Graham, I.; Ray, K.K.; Packard, C.J.; Bruckert, E.; et al. Low-density lipoproteins cause atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. 1. Evidence from genetic, epidemiologic, and clinical studies. A consensus statement from the European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel. Eur Heart J. 2017, 38, 2459–2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabatine, M.S.; Giugliano, R.P.; Keech, A.C.; Honarpour, N.; Wiviott, S.D.; Murphy, S.A.; et al.; FOURIER Steering Committee and Investigators Evolocumab and Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Cardiovascular Disease. N Engl J Med. 2017, 376, 1713–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mach, F.; Baigent, C.; Catapano, A.L.; Koskinas, K.C.; Casula, M.; Badimon, L.; et al.; ESCScientific Document Group 2019 ESC/EASGuidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: Lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. Eur Heart J. 2020, 41, 111–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2022 by the author. Attribution-Non-Commercial-NoDerivatives 4.0.

Share and Cite

Mach, F.; Gallino, A.; Haegeli, L.M.; Kobza, R.; Koskinas, K.; Miserez, A.; Nanchen, D.; Pedrazzini, G.; Räber, L.; Sudano, I.; et al. Document de Consensus Sur la Prise en Charge du Cholestérol LDL. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 25, w10058. https://doi.org/10.4414/cvm.2022.02110

Mach F, Gallino A, Haegeli LM, Kobza R, Koskinas K, Miserez A, Nanchen D, Pedrazzini G, Räber L, Sudano I, et al. Document de Consensus Sur la Prise en Charge du Cholestérol LDL. Cardiovascular Medicine. 2022; 25(2):w10058. https://doi.org/10.4414/cvm.2022.02110

Chicago/Turabian StyleMach, François, Augusto Gallino, Laurent M. Haegeli, Richard Kobza, Konstantinos Koskinas, André Miserez, David Nanchen, Giovanni Pedrazzini, Lorenz Räber, Isabella Sudano, and et al. 2022. "Document de Consensus Sur la Prise en Charge du Cholestérol LDL" Cardiovascular Medicine 25, no. 2: w10058. https://doi.org/10.4414/cvm.2022.02110

APA StyleMach, F., Gallino, A., Haegeli, L. M., Kobza, R., Koskinas, K., Miserez, A., Nanchen, D., Pedrazzini, G., Räber, L., Sudano, I., Twerenbold, R., Noll, G., Amstein, R., & Lüscher, T. F. (2022). Document de Consensus Sur la Prise en Charge du Cholestérol LDL. Cardiovascular Medicine, 25(2), w10058. https://doi.org/10.4414/cvm.2022.02110