Abstract

Centre-based, multidisciplinary cardiac rehabilitation programmes complying with well-defined minimal requirements are the gold standard for delivering optimal postinterventional care and achieving secondary prevention goals. Owing to barriers linked with programme availability and local or national regulations, further efforts are needed in order to ensure a valid choice of high-quality, evidence-based secondary prevention measures that best fit the patient’s psychosocial situation, cardiovascular risk profile and individual preferences.

Lifestyle changes, including healthy food intake, regular physical activity and long-term adherence to optimal cardioprotective medication, are the main pillars of the long-term management of atherosclerotic disease. For a successful implementation, patients need support by means of a professional multidisciplinary team, which provides the necessary information on the type and severity of their disease, initiates the required behavioural changes, and instructs the patients on how to restart physical activity after an acute coronary event or cardiovascular surgery. Structured cardiac rehabilitation (CR) programmes are recognised as the clinical setting for implementation of such a preventive care strategy [1].

Scientific evidence for cardiac rehabilitation

A multitude of individual studies and meta-analyses document the beneficial effects of CR programmes in patients with coronary artery disease with or without heart failure. For patients who have suffered myocardial infarction and/or undergone coronary revascularisation, attending and completing a programme of exercise-based CR is associated with an absolute risk reduction in cardiovascular mortality from 7.6 to 10.4% compared with those who do not take part in a CR programme, with a number needed to treat (NNT) of 37.

The effect of CR on recurrent myocardial infarction and repeat revascularisation seems to be neutral; however, there is a significant reduction in acute hospital admissions (from 30.7 to 26.1%, NNT 22), which is a key determinant of the intervention’s overall cost-efficacy [2]. For individuals with a diagnosis of heart failure, CR may not reduce total mortality, but does impact favourably on hospitalisation, with a 25% relative risk reduction in overall hospital admissions and a 39% reduction (NNT 18) in acute heart failure related episodes [3]. Accordingly, the most recent European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice state that in individuals at very high cardiovascular risk, multimodal interventions integrating medical resources with education on healthy lifestyle, physical activity and stress management, and counselling on psychosocial risk factors, are recommended with a class I, evidence A indication [4].

However, despite of all available evidence, some doubts persist on the efficacy of CR in the modern era. Although a most recent meta-analysis of randomised and nonrandomised controlled studies (The Cardiac Rehabilitation Outcome Study [CROS]) confirmed a significant reduction of mortality for CR participants after an acute coronary syndrome or after coronary artery bypass surgery in prospective or retrospective cohort studies, the single randomised controlled trial available so far (RAMIT: multicentre randomised controlled trial of comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation in patients following acute myocardial infarction) showed a neutral result [5]. In fact, no benefit for survival, psychosocial status or health related quality of life was shown in that study. Furthermore, the CR group was less likely to be physically active at 12 months than the control group. However, because it was greatly underpowered (having recruited at best only 23% of the original predefined sample in each trial arm), RAMIT cannot be viewed as a trial of “efficacy”, that is, to demonstrate whether or not CR “works”, but as a pragmatic trial of its effectiveness as provided “in real life” [1]. It raised concerns due to considerable differences between the centres that recruited patients with respect to content, duration, intensity and volume of the intervention offered to patients. In fact, huge varieties in programme components were noticed, such as:

- –

- staffing levels and multidisciplinary involvement (e.g., dietetics, physiotherapy, psychology, occupational therapy);

- –

- duration and frequency (e.g., 4 to 20 weeks, once or twice weekly);

- –

- intensity of exercise prescribed;

- –

- methods used to change health behaviour (e.g., lectures, cognitive behavioural methods, written materials);

- –

- method of delivery (e.g., individual, group-based with “home exercise”, outpatient, self-management at home, home-based and menu-based).

These variations in funding, staffing, content of the programme and referral across CR programmes in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, where the study has been performed, have been judged unjustifiable by the British Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation (BACPR), and huge efforts have been made to ensure minimum standards, structure and function of CR programmes. It is clear that ineffective delivery of CR is not a problem specific to the UK, and their standards should be taken as an example for the whole of Europe.

Minimal standards and core components of CR programmes

In order to achieve the proven effectiveness of CR in routine clinical practice, the definition, implementation and continuous monitoring of accepted minimal standards for CR delivery are constantly reviewed by the BACPR. Their conclusions on the current evidence of best practice have been summarised in a position paper, which provides a pragmatic summary of the minimum standards, structure and function of cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation programmes (http://www.bacpr.com/resources/AC6_BACPRStandards&CoreComponents2017.pdf) (Table 1). In this, clinical audit of all CR programmes and establishment of national datasets are seen as essential as a basis for checking and benchmarking and to ensure that services are being delivered effectively.

Table 1.

Six standards for cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation (adapted from the British Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation; www.bacpr.com).

As the basis for the elaboration of their recommendations, the BACPR used the following definition: CR is the “coordinated sum of activities required to influence favourably the underlying cause of cardiovascular disease, as well as to provide the best possible physical, mental and social conditions, so that the patients may, by their own efforts, preserve or resume optimal functioning in their community and through improved health behaviour, slow or reverse progression of disease”. Table 2 summarises the six core components which constitute the “coordinated sum of activities” by which CR programmes should improve physical health and quality of life, as well as equip and support people in developing the necessary skills to successfully manage themselves.

Table 2.

The six core components for cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation (adapted from the British Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation; www.bacpr.com).

In Switzerland, the definition of and compliance with the national quality standards, including the maintenance of a national database, is ensured by the Swiss working group for Cardiovascular Prevention, Rehabilitation and Sports Cardiology (SCPRS). The official recognition of each CR programme by the SCPRS is a prerequisite for reimbursement by healthcare providers. The quality standards and adherence to the guidelines are monitored by means of regular audits.

Barriers to the implementation of secondary prevention

Although the CR community still struggles to achieve optimal service delivery, secondary prevention measures have greatly improved over recent decades. Starting from simple bedside consultations lasting a few minutes, they have evolved into professionally led multidisciplinary interventions within CR services. However, it is estimated that, of eligible patients, only 14 to 35% of heart attack survivors and 31% of patients after coronary artery bypass surgery participate in secondary prevention programmes and that 70% of suitable patients do not receive dedicated interventions for risk factor reduction [7]. Patient related factors, as well as gaps caused by healthcare providers and/or health system-based barriers are held responsible (Table 3). The most critical obstacles, however, are the lack of initial referral and insufficient reimbursement strategies [8]. For Switzerland, no reliable numbers regarding referral of patients to CR services exist. Whereas referral after surgery or ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) seems to be well accepted from the clinician/health care provider as well as the patient side, major improvements however are still needed in patients after minor acute coronary syndromes (non-STEMI), elective percutaneous coronary interventions and heart failure.

Table 3.

Patient, healthcare provider and health system-based barriers to implementation of secondary prevention measures [9].

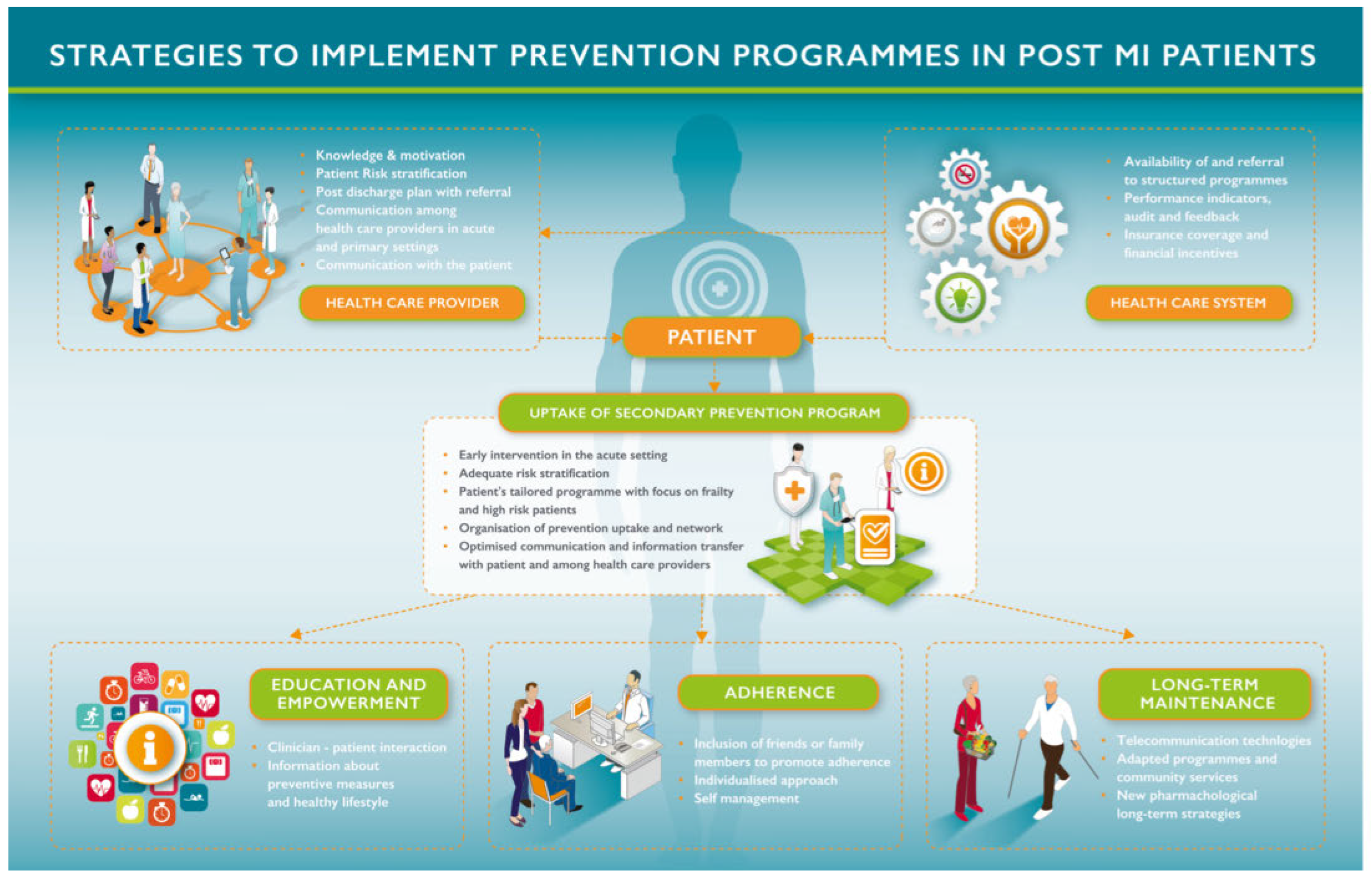

Acknowledging the formally shared responsibilities of all professionals involved in a cardiac patient’s care (nurses, general practitioners, intensivists, acute invasive cardiologists and cardiovascular surgeons), the European Association for Preventive Cardiology (EACP), the Acute Cardiovascular Care Association (ACCA) and the Council on Cardiovascular Nursing and Allied Professions (CCNAP) started a collaborative project to increase awareness of the various gaps and how possibly to overcome them. The summary of a thorough review of the literature and the shared analysis of gaps and a proposed plan of action is summarised in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Strategies to address the lack of referral and to improve enrolment in cardiovascular secondary prevention programmes [9].

Alternative methods of CR

Although structured, exercise-based secondary prevention programmes as described above are the most studied modality of secondary prevention interventions in patients after an acute myocardial infarction, programme uptake and adherence proves to be particularly challenging, and innovative strategies to address these problems have been evaluated. They differ from the traditional models of CR, which are generally organised in three phases (e.g., post-intervention on the ward, post-discharge and long-term), involving residential, ambulatory community-, or home-based programmes. Whereas the aims of outpatient and residential inpatient programmes in terms of secondary prevention are identical, the latter are specifically structured to provide ongoing medical care and individualised training, reserved for high-risk patients or for those for whom the attendance of an ambulatory programme is for various reasons impossible [10]. For historical, structural or logistical reasons, settings of CR vary in different countries across Europe [7].

To comply with programme availability, as well as local and national regulations, a certain number of alternative CR models have developed. Among them, the most important are:

- –

- Multifactorial individualised telehealth delivery: addresses multiple risk factors and provides individualised assessment and risk factor modification, mostly by telephone contact

- –

- Internet-based delivery: majority of patient–provider contact for risk factor modification via the internet

- –

- Telehealth interventions focusing on exercise, mostly by telephone contact, ohen including the use of telemonitoring

- –

- Telehealth interventions focusing on recovery: mostly by telephone contact and the intervention content focused on supporting psychosocial recovery from an acute cardiac event such as myocardial infarction or coronary artery bypass grah surgery

- –

- Community- or home-based CR: mostly delivered face-to-face, through either home visits or patient attendance at community centres (for programmes other than traditional CR)

- –

- Programmes specific to rural, remote, and culturally and linguistically diverse populations

- –

- Multiple models of care: multifaceted interventions across a number of these categories

- –

- Complementary and alternative medicine interventions

However, only the community- and telehealth-based individualised and multifactorial models for CR were found in studies to be associated with improvements in cardiovascular disease risk factor profile similar to those with the traditional hospital-based approach. Therefore, in the most recent European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice, alternative rehabilitation models are rated as follows [4]:

- –

- Home-based rehabilitation with or without telemonitoring holds promise for increasing participation and supporting behavioural change.

- –

- Home-based rehabilitation programmes have the potential to increase patient participation by offering greater flexibility and options for activities.

Regarding the situation in Switzerland, due to the short distances and a dense net of CR programmes, the need for alternative methods of CR delivery seems not to be of major importance. To be considered in the future, new forms of CR need to achieve the same level of scientific evidence for improvement in clinical endpoints as the established methods, which constitute the gold standard.

In the meantime, alternative forms of endurance training, such as ballroom dancing or, for example, exergaming [11,12] could be considered in order to increase the attractiveness of the services and to contribute to overcoming some of the barriers to participation and long-term adherence.

Disclosure statement

No financial support and no other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- Piepoli, M.F.; Corra, U.; Benzer, W.; Bjarnason-Wehrens, B.; Dendale, P.; Gaita, D.; McGee, H.; et al. Cardiac Rehabilitation Section of the European Association of Cardiovascular P, Rehabilitation. Secondary prevention through cardiac rehabilitation: from knowledge to implementation. A position paper from the Cardiac Rehabilitation Section of the European Association of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2010, 17, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dalal, H.M.; Doherty, P.; Taylor, R.S. Cardiac rehabilitation. BMJ 2015, 351, h5000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagar, V.A.; Davies, E.J.; Briscoe, S.; Coats, A.J.; Dalal, H.M.; Lough, F.; et al. Exercise-based rehabilitation for heart failure: systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Heart 2015, 2, e000163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piepoli, M.F.; Hoes, A.W.; Agewall, S.; Albus, C.; Brotons, C.; Catapano, A.L.; et al. 2016 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: The Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts): Developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR). Eur J Prev Cardiol 2016, 23, NP1–NP96. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rauch, B.; Davos, C.H.; Doherty, P.; Saure, D.; Metzendorf, M.I.; Salzwedel, A.; et al. Cardiac Rehabilitation Section EAoPCicwtIoMB, Informatics DoMBUoH, the Cochrane M, Endocrine Disorders Group IoGPH-HUDG. The prognostic effect of cardiac rehabilitation in the era of acute revascularisation and statin therapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized and non-randomized studies – The Cardiac Rehabilitation Outcome Study (CROS). Eur J Prev Cardiol 2016, 23, 1914–1939. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Doherty, P.; Lewin, R. The RAMIT trial, a pragmatic RCT of cardiac rehabilitation versus usual care: what does it tell us? Heart 2012, 98, 605–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjarnason-Wehrens, B.; McGee, H.; Zwisler, A.D.; Piepoli, M.F.; Benzer, W.; Schmid, J.P.; et al. Cardiac Rehabilitation Section European Association of Cardiovascular P, Rehabilitation. Cardiac rehabilitation in Europe: results from the European Cardiac Rehabilitation Inventory Survey. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2010, 17, 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urbinati, S.; Olivari, Z.; Gonzini, L.; Savonitto, S.; Farina, R.; Del Pinto, M.; et al. Investigators B-. Secondary prevention after acute myocardial infarction: drug adherence, treatment goals, and predictors of health lifestyle habits. The BLITZ-4 Registry. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2015, 22, 1548–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piepoli, M.F.; Corra, U.; Dendale, P.; Frederix, I.; Prescott, E.; Schmid, J.P.; et al. Challenges in secondary prevention after acute myocardial infarction: A call for action. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2016, 23, 1994–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Völler, H.; Reibis, R.; Schwaab, B.; Schmid, J.P. Setting and delivery of preventive cardiology. Hospital-based rehabilitation units. In The ESC Textbook of Preventive Cardiology; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2015; Part 4; pp. 285–293. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, T.; Gonzales, A.I.; Sties, S.W.; Carvalho, G.M. Cardiovascular rehabilitation, ballroom dancing and sexual dysfunction. Arq Bras Cardiol 2013, 101, e107–e108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaarsma, T.; Klompstra, L.; Ben Gal, T.; Boyne, J.; Vellone, E.; Back, M.; et al. Increasing exercise capacity and quality of life of patients with heart failure through Wii gaming: the rationale, design and methodology of the HF-Wii study; a multicentre randomized controlled trial. Eur J Heart Fail 2015, 17, 743–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2018 by the author. Attribution - Non-Commercial - NoDerivatives 4.0.