Changes in Physical Fitness, Bone Mineral Density and Body Composition During Inpatient Treatment of Underweight and Normal Weight Females with Longstanding Eating Disorders

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Aim of the Study

2. Methods

2.1. Sample

2.2. Design

2.3. Assessments

2.3.1. ED Psychopathology

2.3.2. Physical Activity

2.3.3. Aerobic Capacity

2.3.4. Muscular Strength

2.3.5. Body Composition and BMD

2.4. Statistics

3. Results

| BMI < 18.5 | BMI ≥ 18.5 | t-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 7) | (n = 22) | ||

| Age (years) | 31.9 (9.4) | 30.6 (9.0) | 0.3 |

| Height (cm) | 164.4 (6.8) | 169.0 (5.9) | 1.9 |

| Total body weight (kg) | 46.0 (6.6) | 65.4 (9.8) | 5.2 *** |

| Lean body mass (kg) | 37.2 (3.6) | 43.2 (4.8) | 3.3 ** |

| Body fat (%) | 15.9 (9.2) | 30.5 (8.9) | 4.1 *** |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 16.8 (1.5) | 22.6 (2.6) | 5.6 *** |

| Weekly PA (counts/min) | 727.3 (372.4) | 595.0 (196.5) | 1.3 |

| PA four weeks prior to admission (min/week) | 236.7 (505.4) | 247.8 (349.0) | 0.07 |

| DSM-IV diagnosis: | |||

| Anorexia Nervosa | 3 (43) | 0 (0) | |

| Bulimia Nervosa | 1 (14) | 11 (50) | |

| ED not otherwise specified | 3 (43) | 11 (50) | |

| ED duration (years) | 16.7 (9.4) | 14.8 (7.8) | 0.5 |

| EDE global score | 4.5 (0.5) | 4.5 (0.8) | 0.01 |

| Treatment duration (weeks) | 20.7 (5.0) | 14.2 (4.9) | 3.3 ** |

3.1. Changes in Physical Fitness and BMD

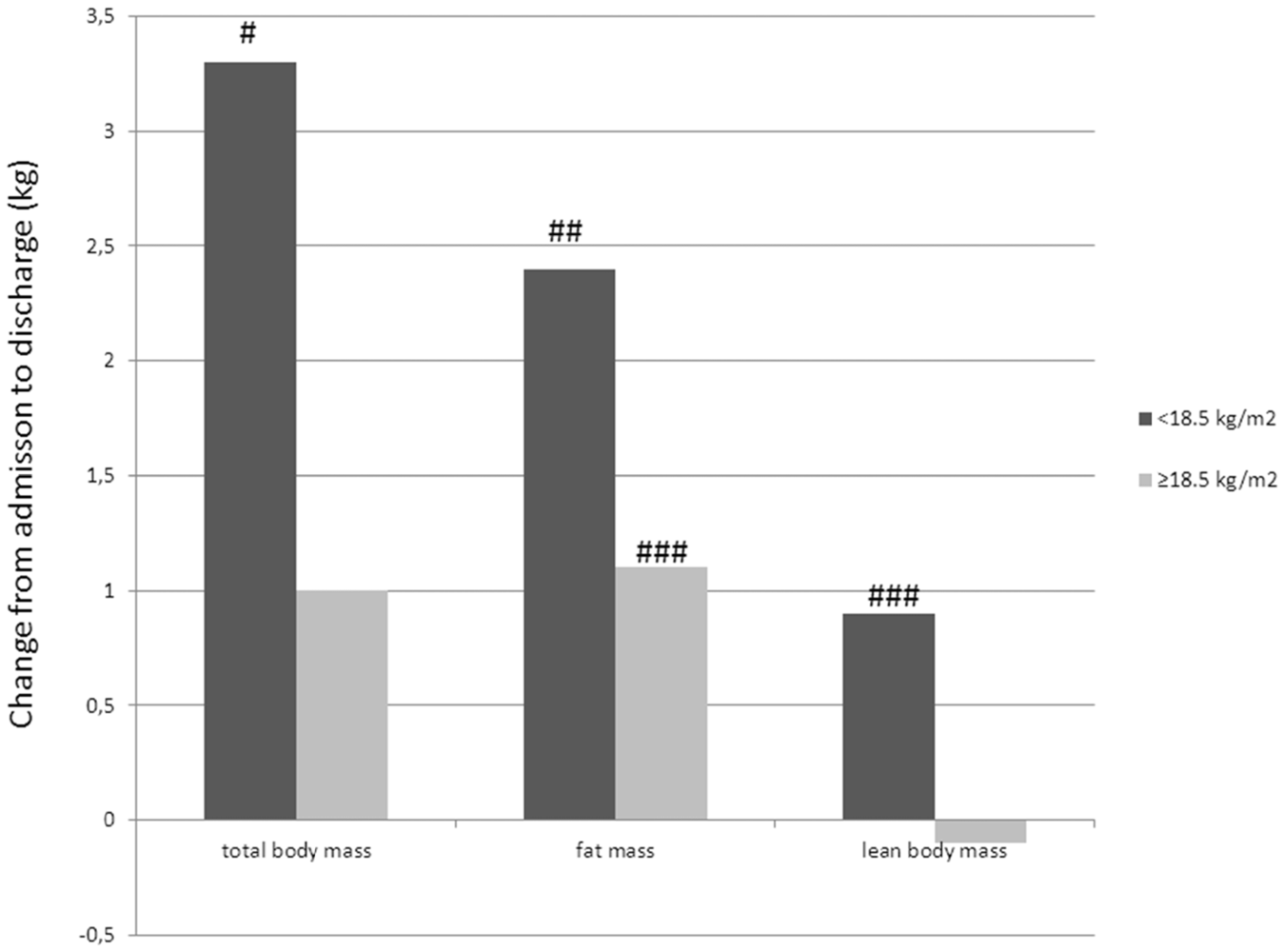

3.2. Changes in Body Composition

| BMI < 18.5 (n = 7) | BMI >18.5 (n = 22) | Diff BMI groups | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adm | Dis | Adm | Dis | Adm | Dis | |

| Physical fitness | ||||||

| VO2max (mL/kg/min) | 42.2 (6.1) | 43.7 (4.8) | 37.9 (9.4) | 38.4 (5.8) | ||

| VE (l/min) | 71.9 (21.6) | 78.7 (24.1) * | 90.2 (18.9) | 91.2 (18.9) | * | |

| RER | 1.24 (0.09) | 1.22 (0.06) | 1.22 (0.08) | 1.20 (0.08) | ||

| 1RM leg press (kg) | 60.8 (23.1) | 77.1 (24.8) *** | 100.8 (31.7) | 107.1 (32.3) | ** | * |

| 1RM seated chest press (kg) | 24.6 (6.6) | 34.2 (8.8) | 33.3 (10.5) | 39.6 (10.3) ** | ||

| Bone health | ||||||

| BMC (g) | 2123.4 (252.3) | 2127.9 (248.3) | 2632.1 (402.8) | 2657.7 (432.0) | ** | ** |

| BMD lumbar spine (g/m2) | 1.07 (0.14) | 1.08 (0.14) * | 1.22 (0.16) | 1.23 (0.15) | * | * |

| Z-score lumbar spine | −1.10 (1.13) | −0.97 (1.21) * | 0.11 (1.34) | 0.22 (1.29) * | * | * |

| BMD femur neck (g/m2) | 0.85 (0.13) | 0.85 (0.12) | 1.02 (0.17) | 1.02 (0.17) | * | * |

| Z-score femur neck | −1.40 (1.08) | −1.28 (1.20) | −0.05 (1.29) | −0.02 (1.28) | * | * |

| Age (years) | Treatment (weeks) | BMI admission | BMI discharge | % change | BF admission | BF discharge | % change | A/G ratio admission | A/G ratio discharge | % change | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI < 18.5 | |||||||||||

| #1 | 48.5 | 22 | 14.6 | 17.0 | 16.4 | 4.2 | 14.1 | 9.9 | 0.90 | 0.69 | −23.3 |

| #2 | 33.9 | 17 | 16.7 | 19.0 | 13.8 | 5.4 | 11.5 | 5.7 | 0.37 | 0.51 | 37.8 |

| #3 | 28.4 | 10 | 17.2 | 18.0 | 4.7 | 20.6 | 25.5 | 4.9 | 0.68 | 0.82 | 20.6 |

| #4 | 20.6 | 22 | 18.2 | 18.7 | 2.8 | 25.3 | 24.2 | −0.9 | 0.68 | 0.61 | −4.4 |

| #5 | 30.3 | 25 | 15.0 | 16.2 | 8.0 | 9.1 | 17.0 | 7.9 | 0.32 | 0.60 | 87.5 |

| #6 | 28.3 | 24 | 17.4 | 18.5 | 6.3 | 12.4 | 13.6 | 1.2 | 0.25 | 0.23 | −8.0 |

| #7 | 42.1 | 22 | 18.4 | 20.2 | 9.8 | 22.2 | 24.7 | 2.5 | 0.41 | 0.43 | 4.9 |

| BMI ≥ 18.5 | |||||||||||

| #8 | 21.3 | 18 | 19.9 | 20.8 | 4.5 | 25.2 | 29.9 | 4.7 | 0.66 | 0.68 | 3.0 |

| #9 | 23.5 | 21 | 21.9 | 21.7 | −0.9 | 27.4 | 31.0 | 3.6 | 0.88 | 0.94 | 6.8 |

| #10 | 27.3 | 26 | 19.9 | 21.0 | 5.5 | 25.5 | 29.3 | 3.6 | 0.81 | 0.92 | 13.6 |

| #11 | 27.0 | 11 | 20.3 | 20.3 | 0.0 | 31.9 | 31.6 | −0.3 | 0.79 | 0.89 | 12.7 |

| #12 | 23.9 | 21 | 20.4 | 21.0 | 2.9 | 23.5 | 26.0 | 2.9 | 0.60 | 0.70 | 16.7 |

| #13 | 25.3 | 20 | 20.5 | 22.3 | 8.8 | 24.6 | 32.1 | 7.5 | 0.76 | 0.84 | 10.3 |

| #14 | 27.3 | 21 | 24.6 | 24.6 | 0.0 | 29.0 | 31.2 | 2.2 | 0.70 | 0.69 | −1.4 |

| #15 | 38.5 | 10 | 20.4 | 19.4 | −4.9 | 21.7 | 17.5 | −4.2 | 0.62 | 0.47 | −24.2 |

| #16 | 39.2 | 10 | 24.2 | 25.0 | 3.3 | 42.4 | 44.6 | 2.2 | 0.96 | 0.94 | −2.1 |

| #17 | 53.8 | 20 | 20.8 | 21.7 | 4.3 | 14.3 | 18.8 | 4.5 | 0.47 | 0.47 | 0 |

| #18 | 37.8 | 13 | 22.8 | 22.3 | −2.2 | 35.4 | 33.8 | −1.6 | 0.93 | 0.82 | −11.8 |

| #19 | 43.5 | 13 | 24.1 | 24.2 | 0.4 | 37.3 | 37.2 | −0.1 | 1.02 | 0.97 | −4.9 |

| #20 | 23.1 | 20 | 21.5 | 23.1 | 7.4 | 31.6 | 34.0 | 2.4 | 0.63 | 0.73 | 15.9 |

| #21 | 21.5 | 20 | 23.4 | 23.6 | 0.5 | 26.6 | 28.6 | 2 | 0.64 | 0.63 | −1.6 |

| #22 | 22.0 | 19 | 23.8 | 24.0 | 0.8 | 36.4 | 38.9 | 2.5 | 0.78 | 0.73 | −6.4 |

| #23 | 26.4 | 12 | 19.8 | 20.4 | 3.0 | 36.1 | 32.8 | −3.3 | 0.88 | 0.80 | −9.1 |

| #24 | 26.6 | 12 | 20.3 | 22.6 | 11.3 | 30.6 | 32.0 | 1.9 | 0.65 | 0.67 | 3.1 |

| #25 | 37.4 | 22 | 19.5 | 19.9 | 2.1 | 13.4 | 18.6 | 5.2 | 0.23 | 0.30 | 30.4 |

| #26 | 18.0 | 11 | 25.7 | 24.0 | −6.9 | 34.1 | 31.4 | −2.7 | 0.97 | 0.78 | −19.9 |

| #27 | 27.3 | 10 | 26.1 | 25.7 | −1.5 | 42.2 | 42.5 | 0.3 | 0.90 | 0.93 | 3.3 |

| #28 | 31.6 | 10 | 26.4 | 26.0 | −1.5 | 41.8 | 41.5 | −0.3 | 1.06 | 0.99 | −6.6 |

| #29 | 44.1 | 10 | 29.3 | 30.1 | 2.7 | 41.8 | 40.8 | −1 | 1.02 | 0.98 | −3.9 |

| Change total body weight (kg) | Change BMI (kg/m2) | Change body fat (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Change EDI | |||

| Total score | 0.28 | −0.26 | −0.13 |

| Drive for thinness | 0.20 | −0.11 | 0.06 |

| Body dissatisfaction | 0.49 * | 0.44 * | 0.26 |

| Bulimia | 0.51 ** | 0.46 * | 0.36 |

| Ineffectiveness | 0.25 | 0.22 | −0.05 |

| Maturity fears | −0.28 | −0.25 | −0.14 |

| Perfectionism | 0.06 | 0.02 | −0.05 |

| Interpersonal distrust | 0.04 | 0.01 | −0.11 |

| Interoceptive awareness | 0.14 | 0.24 | 0.39 |

| Asceticism | 0.17 | 0.09 | −0.06 |

| Social insecurity | 0.13 | 0.13 | −0.20 |

| Impulse regulation | 0.15 | 0.08 | −0.10 |

| Change EDE | |||

| Global score | −0.03 | −0.08 | −0.12 |

| Restraint | −0.41 * | −0.44 * | −0.31 |

| Eating concern | −0.14 | −0.16 | −0.15 |

| Weight concern | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.06 |

| Shape concern | 0.26 | 0.22 | 0.13 |

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Clinical and Scientific Implications

5. Conclusions

Conflict of Interest

References

- Mitchell, J.E.; Crow, S. Medical complications of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Curr.Opin.Psychiatry 2006, 19, 438–443. [Google Scholar]

- Bratland-Sanda, S.; Sundgot-Borgen, J.; Ro, O.; Rosenvinge, J.H.; Hoffart, A.; Martinsen, E.W. "I’m not physically active—I only go for walks”: Physical activity in patients with longstanding eating disorders. Int. J. Eat Disord. 2010, 43, 88–92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mond, J.M.; Calogero, R.M. Excessive exercise in eating disorder patients and in healthy women. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2009, 43, 227–234. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen, B.K.; Saltin, B. Evidence for prescribing exercise as therapy in chronic disease. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2006, 16, 3–63. [Google Scholar]

- Hausenblas, H.A.; Symons Downs, D. Exercise dependence: A systematic review. Psychol. Sports Exerc. 2002, 3, 89–123. [Google Scholar]

- Symons Downs, D.; Hauseblas, H.A. I can’t stop: The relationship among exercise dependence symptoms, injury and illness behaviors, and motives for exercise continuance. J. Hum. Mov. Stud. 2003, 45, 359–375. [Google Scholar]

- Fogelholm, M. Physical activity, fitness and fatness: Relations to mortality, morbidity and disease risk factor. A systematic review. Obes. Rev. 2010, 11, 202–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bratland-Sanda, S.; Sundgot-Borgen, J.; Rosenvinge, J.H.; Ro, O.; Hoffart, A.; Martinsen, E.W. Physical fitness, bone mineral density and associations with physical activity in females with longstanding eating disorders and non-clinical controls. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fitness 2010, 50, 303–310. [Google Scholar]

- McLoughlin, D.M.; Spargo, E.; Wassif, W.S.; Newham, D.J.; Peters, T.J.; Lantos, P.L.; Russell, G.F. Structural and functional changes in skeletal muscle in anorexia nervosa. Acta Neuropathol.(Berl.) 1998, 95, 632–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fohlin, L.; Freyschuss, U.; Bjarke, B.; Davies, C.T.; Thoren, C. Function and dimensions of the circulatory system in anorexia nervosa. Acta Paediatr. Scand. 1978, 67, 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Nudel, D.B.; Gootman, N.; Nussbaum, M.P.; Shenker, I.R. Altered exercise performance and abnormal sympathetic responses to exercise in patients with anorexia nervosa. J. Pediatr. 1984, 105, 34–37. [Google Scholar]

- Waller, E.G.; Wade, A.J.; Treasure, J.; Ward, A.; Leonard, T.; Powell-Tuck, J. Physical measures of recovery from anorexia nervosa during hospitalised re-feeding. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 1996, 50, 165–170. [Google Scholar]

- Rigaud, D.; Moukaddem, M.; Cohen, B.; Malon, D.; Reveillard, V.; Mignon, M. Refeeding improves muscle performance without normalization of muscle mass and oxygen consumption in anorexia nervosa patients. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1997, 65, 1845–1851. [Google Scholar]

- Fohlin, L. Exercise performance and body dimensions in anorexia nervosa before and after rehabilitation. Acta Med. Scand. 1978, 204, 61–65. [Google Scholar]

- Tokumura, M.; Yoshiba, S.; Tanaka, T.; Nanri, S.; Watanabe, H. Prescribed exercise training improves exercise capacity of convalescent children and adolescents with anorexia nervosa. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2003, 162, 430–431. [Google Scholar]

- Sundgot-Borgen, J.; Rosenvinge, J.H.; Bahr, R.; Schneider, L.S. The effect of exercise, cognitive therapy, and nutritional counseling in treating bulimia nervosa. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2002, 34, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chantler, I.; Szabo, C.P.; Green, K. Muscular strength changes in hospitalized anorexic patients after an eight week resistance training program. Int. J. Sports Med. 2006, 27, 660–665. [Google Scholar]

- Del Valle, M.F.; Perez, M.; Santana-Sosa, E.; Fiuza-Luces, C.; Bustamante-Ara, N.; Gallardo, C.; Villasenor, A.; Graell, M.; Morande, G.; Romo, G.R.; et al. Does resistance training improve the functional capacity and well being of very young anorexic patients? A randomized controlled trial. J. Adolesc. Health 2010, 46, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misra, M.; Klibanski, A. Anorexia nervosa and osteoporosis. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2006, 7, 91–99. [Google Scholar]

- Sundgot-Borgen, J.; Bahr, R.; Falch, J.A.; Schneider, L.S. Normal bone mass in bulimic women. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1998, 83, 3144–3149. [Google Scholar]

- Naessen, S.; Carlstrom, K.; Glant, R.; Jacobsson, H.; Hirschberg, A.L. Bone mineral density in bulimic women—Influence of endocrine factors and previous anorexia. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2006, 155, 245–251. [Google Scholar]

- Newton, J.R.; Freeman, C.P.; Hannan, W.J.; Cowen, S. Osteoporosis and normal weight bulimia nervosa--which patients are at risk? J. Psychosom. Res. 1993, 37, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joyce, J.M.; Warren, D.L.; Humphries, L.L.; Smith, A.J.; Coon, J.S. Osteoporosis in women with eating disorders: Comparison of physical parameters, exercise, and menstrual status with spa and dpa evaluation. J. Nucl. Med. 1990, 31, 325–331. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mehler, P.S.; Mackenzie, T.D. Treatment of osteopenia and osteoporosis in anorexia nervosa: A systematic review of the literature. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2008, 42, 195–201. [Google Scholar]

- Misra, M.; Prabhakaran, R.; Miller, K.K.; Goldstein, M.A.; Mickley, D.; Clauss, L.; Lockhart, P.; Cord, J.; Herzog, D.B.; Katzman, D.K.; et al. Weight gain and restoration of menses as predictors of bone mineral density change in adolescent girls with anorexia nervosa-1. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008, 93, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Viapiana, O.; Gatti, D.; Dalle Grave, R.; Todesco, T.; Rossini, M.; Braga, V.; Idolazzi, L.; Fracassi, E.; Adami, S. Marked increases in bone mineral density and biochemical markers of bone turnover in patients with anorexia nervosa gaining weight. Bone 2007, 40, 1073–1077. [Google Scholar]

- Zipfel, S.; Seibel, M.J.; Lowe, B.; Beumont, P.J.; Kasperk, C.; Herzog, W. Osteoporosis in eating disorders: A follow-up study of patients with anorexia and bulimia nervosa. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001, 86, 5227–5233. [Google Scholar]

- McArdle, W.D.; Katch, F.I.; Katch, V.L. Sports & Exercise Nutrition; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Baltimore, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, D.; Heymsfield, S.B.; Heo, M.; Jebb, S.A.; Murgatroyd, P.R.; Sakamoto, Y. Healthy percentage body fat ranges: An approach for developing guidelines based on body mass index. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000, 72, 694–701. [Google Scholar]

- American College of Sports Medicine, Whaley, M.H.; Brubaker, P.H.; Otto, R.M.; Armstrong, L.E. Acsm’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Baltimore, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kerem, N.C.; Katzman, D.K. Brain structure and function in adolescents with anorexia nervosa. Adolesc. Med. 2003, 14, 109–118. [Google Scholar]

- Roberto, C.A.; Mayer, L.E.; Brickman, A.M.; Barnes, A.; Muraskin, J.; Yeung, L.K.; Steffener, J.; Sy, M.; Hirsch, J.; Stern, Y.; et al. Brain tissue volume changes following weight gain in adults with anorexia nervosa. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2011, 44, 406–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chui, H.T.; Christensen, B.K.; Zipursky, R.B.; Richards, B.A.; Hanratty, M.K.; Kabani, N.J.; Mikulis, D.J.; Katzman, D.K. Cognitive function and brain structure in females with a history of adolescent-onset anorexia nervosa. Pediatrics 2008, 122, e426–e437. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, L.; Walsh, B.T.; Pierson, R.N., Jr.; Heymsfield, S.B.; Gallagher, D.; Wang, J.; Parides, M.K.; Leibel, R.L.; Warren, M.P.; Killory, E.; et al. Body fat redistribution after weight gain in women with anorexia nervosa. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 81, 1286–1291. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, L.E.; Klein, D.A.; Black, E.; Attia, E.; Shen, W.; Mao, X.; Shungu, D.C.; Punyanita, M.; Gallagher, D.; Wang, J.; et al. Adipose tissue distribution after weight restoration and weight maintenance in women with anorexia nervosa. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 90, 1132–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaye, W.H.; Gwirtsman, H.E.; Obarzanek, E.; George, D.T. Relative importance of calorie intake needed to gain weight and level of physical activity in anorexia nervosa. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1988, 47, 989–994. [Google Scholar]

- Frey, J.; Hebebrand, J.; Muller, B.; Ziegler, A.; Blum, W.F.; Remschmidt, H.; Herpertz-Dahlmann, B.M. Reduced body fat in long-term followed-up female patients with anorexia nervosa. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2000, 34, 83–88. [Google Scholar]

- Hechler, T.; Rieger, E.; Touyz, S.; Beumont, P.; Plasqui, G.; Westerterp, K. Physical activity and body composition in outpatients recovering from anorexia nervosa and healthy controls. Adapt. Phys. Activ. Q. 2008, 25, 159–173. [Google Scholar]

- Touyz, S.W.; Lennerts, W.; Arthur, B.; Beumont, P.J.V. Anaerobic exercise as an adjunct to refeeding patients with anorexia nervosa: Does it compromise weight gain? Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 1993, 1, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norwegian Directorate of Health, Norwegian Recommendations for Nutrition and Physical Activity; The Norwegian Directorate of Health: Oslo, Norway, 2005.

- Ro, O.; Martinsen, E.W.; Rosenvinge, J.H. Treatment of bulimia nervosa—Results from modum bads nervesanatorium. Tidsskr. Nor. Laegeforen. 2002, 122, 260–265. [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn, C.G.; Cooper, Z.; Wilson, G.T. The eating disorders examination. In Binge Eating: Nature, Assessment and Treatment, 12th ed; Guilford: London, UK, 1993; pp. 317–360. [Google Scholar]

- Garner, D.M. Eating Disorders Inventory-2: Professional Manual; Psychological Assessment Resources Inc.: Odessa, FL, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Foss, O.; Hallen, J. Validity and stability of a computerized metabolic system with mixing chamber. Int. J. Sports Med. 2005, 26, 569–575. [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer, W.J.; Ratamess, N.A.; Fry, A.C.; French, D.N.; Maud, P.J.; Foster, C. Strength training: Development and evaluation of methodology. In Physiological Assessment of Human Fitness; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 1995; pp. 119–151. [Google Scholar]

- Leib, E.S.; Lewiecki, E.M.; Binkley, N.; Hamdy, R.C. Official positions of the international society for clinical densitometry. J. Clin. Densitom. 2004, 7, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Bratland-Sanda, S.; Sundgot-Borgen, J.; Ro, O.; Rosenvinge, J.H.; Hoffart, A.; Martinsen, E.W. Physical activity and exercise dependence during inpatient treatment of longstanding eating disorders: An exploratory study of excessive and non-excessive exercisers. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2010, 43, 266–273. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV), 4th ed; APA: Washington, DC, USA, 1994; pp. 539–550.

- Loucks, A.B. Energy balance and body composition in sports and exercise. J. Sports Sci. 2004, 22, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, L.E.; VanHeest, J.L. The unknown mechanism of the overtraining syndrome. Clues from depression and psychoneuroimmunology. Sports Med. 2002, 32, 185–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McArdle, W.D.; Katch, F.I.; Katch, V.L. Exercise Physiology. Energy, Nutrition, and Human Performance, 5th ed; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Baltimore, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lawson, E.A.; Miller, K.K.; Bredella, M.A.; Phan, C.; Misra, M.; Meenaghan, E.; Rosenblum, L.; Donoho, D.; Gupta, R.; Klibanski, A. Hormone predictors of abnormal bone microarchitecture in women with anorexia nervosa. Bone 2010, 46, 458–463. [Google Scholar]

- Tothill, P.; James Hannan, W. Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry measurements of fat and lean masses in subjects with eating disorders. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 2004, 28, 912–919. [Google Scholar]

© 2012 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Bratland-Sanda, S.; Martinsen, E.W.; Sundgot-Borgen, J. Changes in Physical Fitness, Bone Mineral Density and Body Composition During Inpatient Treatment of Underweight and Normal Weight Females with Longstanding Eating Disorders. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2012, 9, 315-330. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph9010315

Bratland-Sanda S, Martinsen EW, Sundgot-Borgen J. Changes in Physical Fitness, Bone Mineral Density and Body Composition During Inpatient Treatment of Underweight and Normal Weight Females with Longstanding Eating Disorders. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2012; 9(1):315-330. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph9010315

Chicago/Turabian StyleBratland-Sanda, Solfrid, Egil W. Martinsen, and Jorunn Sundgot-Borgen. 2012. "Changes in Physical Fitness, Bone Mineral Density and Body Composition During Inpatient Treatment of Underweight and Normal Weight Females with Longstanding Eating Disorders" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 9, no. 1: 315-330. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph9010315

APA StyleBratland-Sanda, S., Martinsen, E. W., & Sundgot-Borgen, J. (2012). Changes in Physical Fitness, Bone Mineral Density and Body Composition During Inpatient Treatment of Underweight and Normal Weight Females with Longstanding Eating Disorders. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 9(1), 315-330. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph9010315