The Strategic Advantage of FQHCs in Implementing Mobile Health Units: Lessons Learned from a Pilot Initiative

Highlights

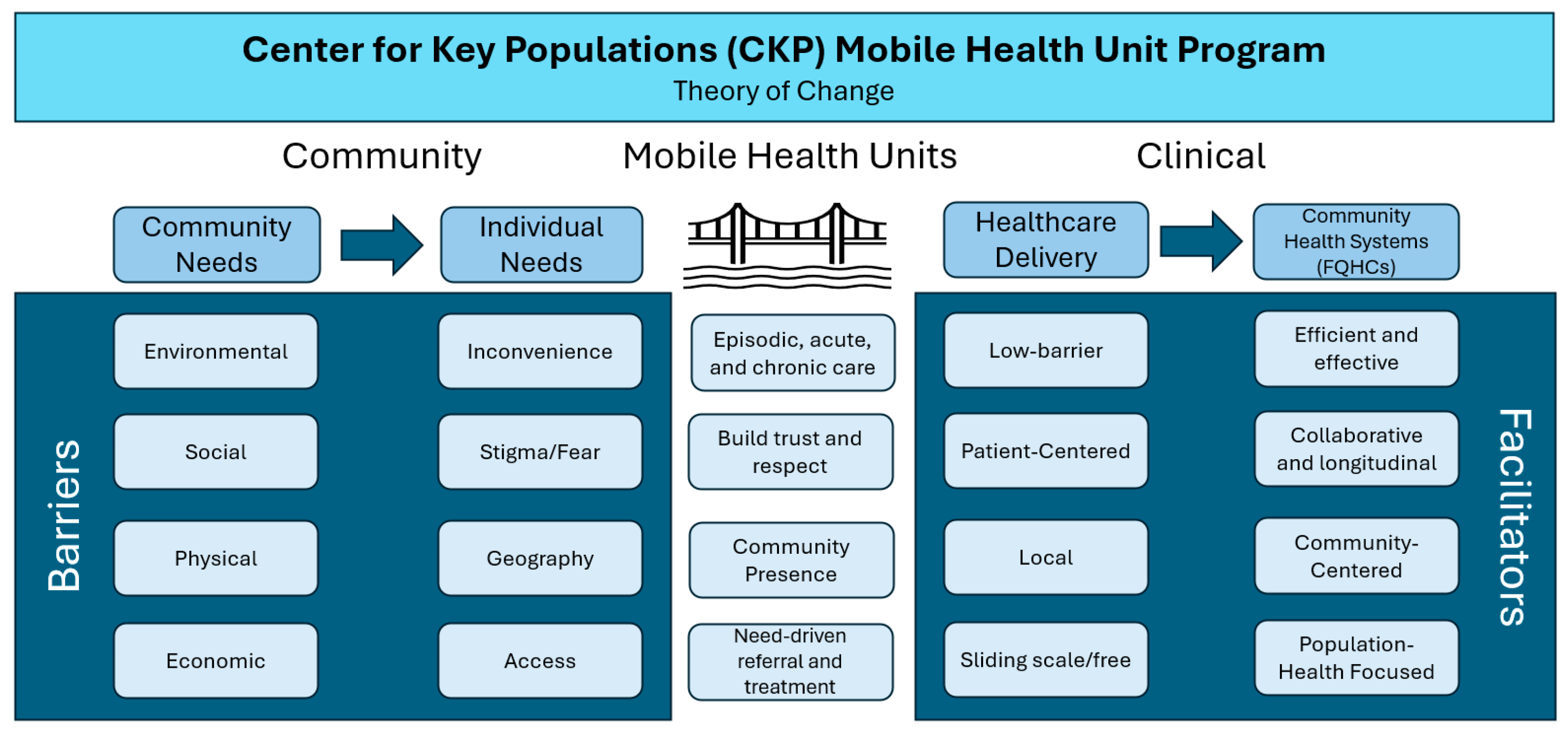

- Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) are community-based and community-led organizations in the United States that receive federal funds to provide comprehensive primary care and support services to community members in underserved areas whose social, economic, environmental, and physical needs may present barriers to accessing and obtaining quality care.

- Mobile Health Units (MHUs) are community-based points of care that can help FQHCs reach populations for whom traditional site-based care remains inaccessible due to systematic barriers and who may not engage with the healthcare system otherwise.

- This descriptive observational implementation study presents initial outcomes of a new MHU program implemented by a large, statewide FQHC system and offers recommendations for FQHCs and similar organizations that are starting a new or expanding an existing MHU program.

- Based on the firsthand experience of our MHU program’s providers, care teams, and program leaders, we offer specific recommendations and lessons learned regarding patient engagement and community connection, MHU logistics, addressing healthcare access needs, and addressing transportation as a barrier.

- The FQHC-led MHU model is a potentially scalable solution for community health centers and other organizations interested in providing patient-centered and community-centered delivery of healthcare services and health-related knowledge to community members.

- Allocating resources to mobile primary care delivery to hard-to-reach populations enhanced our FQHC’s ability to offer proactive, patient-centered care, with the intent of strengthening patients’ engagement with high-quality community-focused primary care.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Setting

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patients Served

3.2. Barriers to Care Prior to MHU Service Delivery

3.3. Recommendations for Policy and Practice and Lessons Learned

3.3.1. Patient Engagement and Community Connection

3.3.2. Logistics

3.3.3. Addressing Healthcare Access Needs

3.3.4. Addressing Transportation as a Barrier

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| U.S. | United States |

| MHU | Mobile health unit |

| FQHC | Federally Qualified Health Center |

| CHCI | Community Health Center, Inc. |

| CT | Connecticut |

| CKP | Center for Key Populations |

| ICD-10 | International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision |

| HIV | Human immunodeficiency virus |

| STI | Sexually transmitted infection |

| HIPAA | Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 |

References

- Health Resources and Services Administration. HRSA Data Warehouse: Health Workforce Shortage Areas. Available online: https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/health-workforce/shortage-areas (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Health Resources and Services Administration, National Center for Health Workforce Analysis. State of the Primary Care Workforce, 2024. Available online: https://bhw.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/bureau-health-workforce/state-of-the-health-workforce-report-2024.pdf (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Sparks, G.; Lopes, L.; Montero, A.; Presiado, M.; Hamel, L. Americans’ Challenges with Health Care Costs; Kaiser Family Foundation: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2025; Available online: https://www.kff.org/health-costs/americans-challenges-with-health-care-costs/ (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- United States Census Bureau. My Community Explorer 4.5. Available online: https://experience.arcgis.com/experience/13a111e06ad242fba0fb62f25199c7dd/page/Page-1 (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Mobile Health Map. What Is Mobile Health Map? Mobile Health Map at Harvard Medical School. Available online: https://www.mobilehealthmap.org/what-we-do (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Malone, N.C.; Williams, M.M.; Smith Fawzi, M.C.; Bennet, J.; Hill, C.; Katz, J.N.; Oriol, N.E. Mobile health clinics in the United States. Int. J. Equity Health 2020, 19, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jindal, M.; Chaiyachati, K.H.; Fung, V.; Manson, S.M.; Mortensen, K. Eliminating health care inequities through strengthening access to care. Health Serv. Res. 2023, 58, 300–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Social Determinants of Health. Healthy People 2030. Available online: https://odphp.health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Friedberg, M.W.; Hussey, P.S.; Schneider, E.C. Primary Care: A Critical Review of The Evidence on Quality and Costs of Health Care. Health Aff. 2010, 29, 766–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Health Resources and Services Administration, Bureau of Primary Health Care. What Is a Health Center? Available online: https://bphc.hrsa.gov/about-health-center-program/what-health-center (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Community Health Center Association of Connecticut. Caring for All of Connecticut. Available online: https://www.chcact.org (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- Connecticut Department of Public Health. Connecticut Primary Care Assessment: A Preliminary Needs Assessment Scan of the Primary Healthcare Sector; Hartford, C.T., Ed.; Connecticut Department of Public Health: Hartford, CT, USA, 2021. Available online: https://portal.ct.gov/-/media/dph/primary-care-office/pcna-finaldraft-v8_122821revised.pdf (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starfield, B.; Shi, L.; Macinko, J. Contribution of Primary Care to Health Systems and Health. Milbank Q. 2005, 83, 457–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Academy of Family Physicians. Primary Care. Available online: https://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/primary-care.html (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Basu, S.; Berkowitz, S.A.; Phillips, R.L.; Bitton, A.; Landon, B.E.; Phillips, R.S. Association of Primary Care Physician Supply with Population Mortality in the United States, 2005–2015. JAMA Intern. Med. 2019, 179, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vimalananda, V.G.; Orlander, J.D.; Afable, M.K.; Fincke, B.G.; Solch, A.K.; Rinne, S.T.; Kim, E.; Cutrona, S.L.; Thomas, D.D.; Stymish, J.L.; et al. Electronic consultations (E-consults) and their outcomes: A systematic review. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2020, 27, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, P. The Coming Surge in Uninsured Patients at Community Health Centers; National Association of Community Health Centers: Washington, DC, USA, 2025; Available online: https://www.nachc.org/the-coming-surge-in-uninsured-patients-at-community-health-centers/ (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Perron, M.E.; Hudon, C.; Roux-Levy, P.H.; Poitras, M.E. Shared decision-making with patients with complex care needs: A scoping review. BMC Prim. Care 2024, 25, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaeffer, M. Prevalence and Factors Associated with Burnout Among Mobile Health Clinic Staff in the United States. Ph.D. Thesis, Saint Louis University, Saint Louis, MO, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/84c300cf8f1ad0c1ab4dea6f085356ff/1 (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- Community Health Center, Inc. Center for Key Populations Fellow—Nurse Practitioner Residency Training Program. Available online: https://www.npresidency.com/program/center-for-key-populations-fellow (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Mobile Healthcare Association. Advancing the Mission: Annual Impact Report 2024. Mobile Healthcare Association. Available online: https://mobilehca.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Impact-Report-2024.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- Coaston, A.; Lee, S.J.; Johnson, J.; Hardy-Peterson, M.; Weiss, S.; Stephens, C. Mobile Medical Clinics in the United States Post-Affordable Care Act: An Integrative Review. Popul. Health Manag. 2022, 25, 264–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christian, N.J.; Havlik, J.; Tsai, J. The Use of Mobile Medical Units for Populations Experiencing Homelessness in the United States: A Scoping Review. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2024, 39, 1474–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | # | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age (N = 581) | ||

| 18–29 | 64 | 11.0 |

| 30–39 | 122 | 21.0 |

| 40–49 | 132 | 22.7 |

| 50–59 | 132 | 22.7 |

| 60–69 | 95 | 16.4 |

| 70+ | 36 | 6.2 |

| Gender (N = 581) | ||

| Female | 173 | 29.8 |

| Male | 408 | 70.2 |

| Ethnicity (N = 581) | ||

| Hispanic | 253 | 43.6 |

| Not Hispanic | 215 | 37.0 |

| Unreported | 113 | 19.4 |

| Race (N = 581) | ||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 3 | 0.5 |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 4 | 0.7 |

| Black or African American | 111 | 19.1 |

| White | 178 | 30.7 |

| More than one | 2 | 0.3 |

| Other or Unknown | 283 | 48.7 |

| Visit Type (N = 1298 visits) | ||

| Medical | 1202 | 92.6 |

| Nursing | 64 | 4.9 |

| Women’s Health | 32 | 2.5 |

| Most Common Clinical Assessments (by ICD-10 code; 1298 visits) 1 | ||

| HIV, Viral hepatitis, and STI screening | 495 | 38.1 |

| Blood Pressure | 321 | 24.7 |

| Pain | 295 | 22.7 |

| Substance Use, Including Tobacco and Alcohol Use | 294 | 22.7 |

| Mental Health | 267 | 20.6 |

| Overweight or Obesity | 259 | 20.0 |

| Diabetes and Pre-Diabetes, including Screening | 255 | 19.6 |

| Maternal and Women’s Healthcare MHU Navigation Services (n = 29 patients) 2 | ||

| Access/Engagement in Healthcare—Primary Care | 16 | 55.2 |

| Medical Transportation | 14 | 48.3 |

| Health-Related Social Need—Housing | 11 | 37.9 |

| Insurance Navigation | 10 | 34.5 |

| Health Risk—Connecticut Early Cancer Detection and Prevention Program | 7 | 24.1 |

| Category | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| Patient Engagement and Community Connection |

|

| |

| |

| |

| Logistics: Electronic Health Record and Electronic Scheduling |

|

| |

| Logistics: Operational Oversight |

|

| Logistics: MHU Team |

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| Addressing Healthcare Access Needs: Enabling Services |

|

| Addressing Healthcare Access Needs: Social Setting |

|

| Addressing Healthcare Access Needs: Trust |

|

| Addressing Healthcare Access Needs: Consistent Care |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bifulco, L.; Rogers, A.; Hackerson, C.; Haddad, M.S.; Damian, A.J.; Harding, K. The Strategic Advantage of FQHCs in Implementing Mobile Health Units: Lessons Learned from a Pilot Initiative. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2026, 23, 158. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23020158

Bifulco L, Rogers A, Hackerson C, Haddad MS, Damian AJ, Harding K. The Strategic Advantage of FQHCs in Implementing Mobile Health Units: Lessons Learned from a Pilot Initiative. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2026; 23(2):158. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23020158

Chicago/Turabian StyleBifulco, Lauren, Anna Rogers, Cecilia Hackerson, Marwan S. Haddad, April Joy Damian, and Kathleen Harding. 2026. "The Strategic Advantage of FQHCs in Implementing Mobile Health Units: Lessons Learned from a Pilot Initiative" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 23, no. 2: 158. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23020158

APA StyleBifulco, L., Rogers, A., Hackerson, C., Haddad, M. S., Damian, A. J., & Harding, K. (2026). The Strategic Advantage of FQHCs in Implementing Mobile Health Units: Lessons Learned from a Pilot Initiative. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 23(2), 158. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23020158