Mobile Eye Units in the United States and Canada: A Narrative Review of Structures, Services and Challenges

Highlights

- Mobile Eye Units (MEUs) directly address persistent population-level barriers to eye care, transportation, insurance limitations, geographic distance, workforce shortages, and language or cultural challenges, that drive preventable vision loss in underserved areas of the U.S. and Canada.

- By bringing screenings, diagnostics, and referral pathways into community settings, MEUs serve groups with elevated risk of uncorrected refractive error, diabetic eye disease, glaucoma, and pediatric vision disorders, conditions that disproportionately affect marginalized communities.

- Vision impairment has broad public health consequences, affecting learning, employment, independence, and chronic disease management. Yet many communities lack accessible eye care infrastructure. MEUs offer a practical and scalable strategy to reduce these disparities.

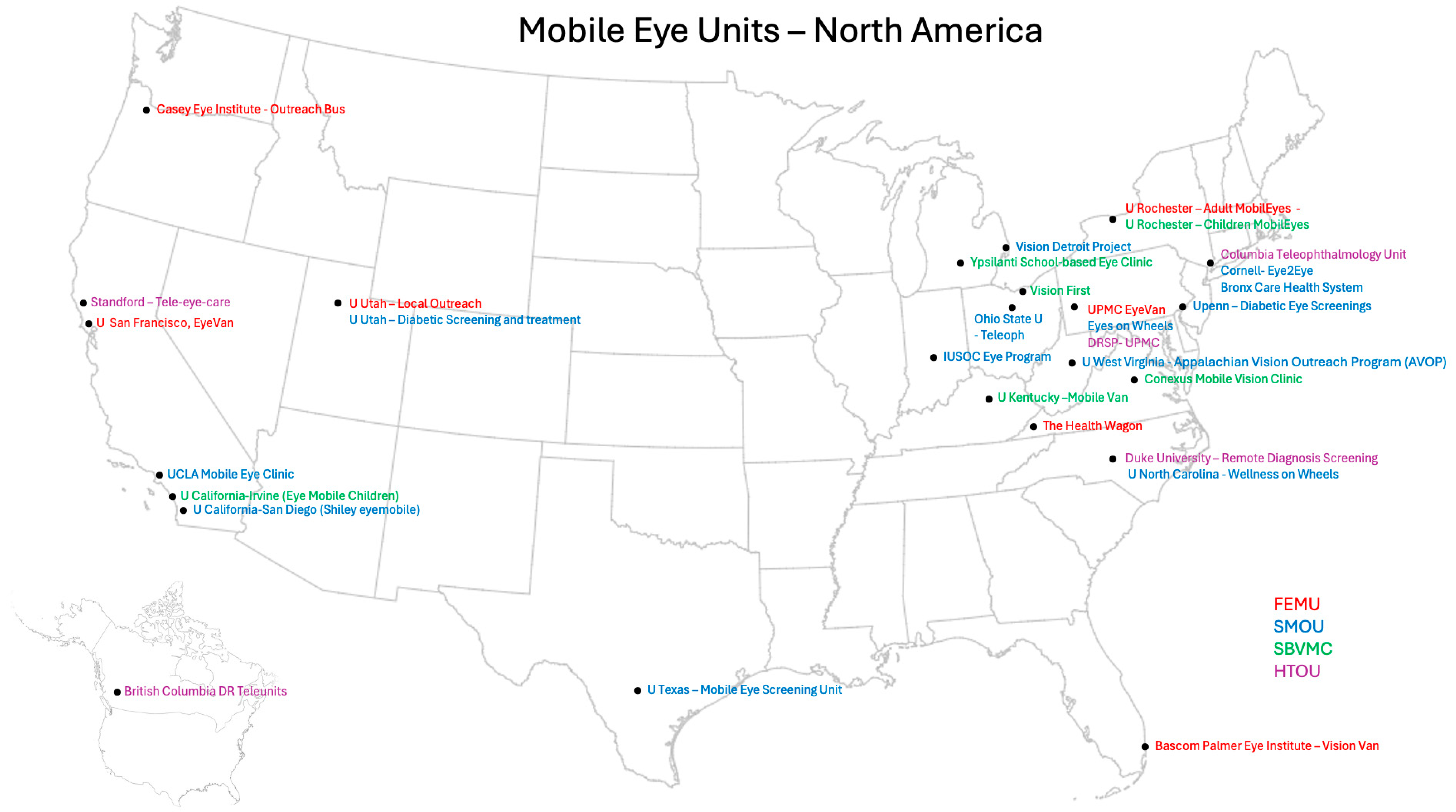

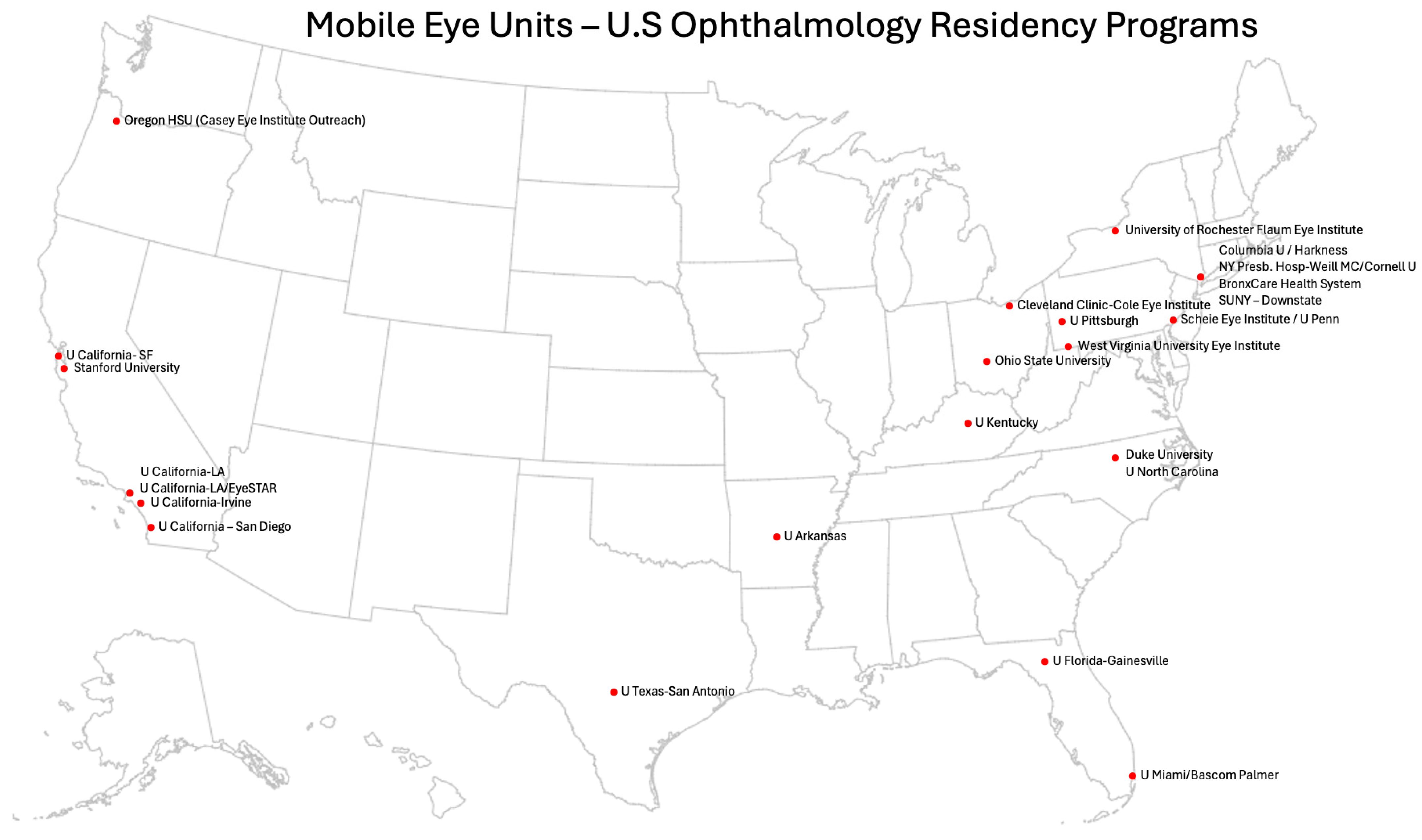

- This review provides the first structured synthesis of MEU models in North America, describing their design, capabilities, limitations, and current gaps, and offering clear guidance on where services exist and where they are absent. By mapping MEU types, summarizing strengths and constraints, and outlining future directions, this work equips public health programs, health systems, and policymakers with a practical framework to identify needs and plan mobile eye care services.

- Practitioners and health systems can use the comparative model descriptions, tables, and geographic mapping in this review as decision-support tools to select the MEU type that best matches their community’s needs and operational capacity, and to strengthen integration of mobile eye care with navigation services and health-system referral pathways.

- Policymakers and researchers should prioritize standardized outcome reporting, improved follow-up systems, and evaluation frameworks to expand the evidence base for MEUs. Identifying gaps in geographic coverage and investing in interoperable digital systems, such as EHR-linked referrals, will be essential for strengthening continuity of care and ensuring mobile eye care programs are sustainable and scalable.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Types of MEU Models

- Fully Equipped Mobile Units (FEMUs)

- Semi-Mobile Outreach Units (SMOUs)

- School-Based Vision Mobile Units (SBVMUs)

- Hybrid Teleophthalmology Units (HTOUs)

3.1.1. Fully Equipped Mobile Health Units (FEMU)

- Description: Self-contained eye clinics built into large vehicles: buses, RVs, or trailers. These units typically have power supply, climate control, and internet connectivity. They are often affiliated with academic centers, public health departments, or non-profits. Typical staffing includes ophthalmologists or optometrists, technicians, trainees, and support staff. Unlike Semi-Mobile Outreach Units (SMOUs), FEMUs deliver care inside the vehicle itself, where diagnostic equipment is permanently installed and not transported to host sites.

- Services Provided: Visual acuity testing, refraction, intraocular pressure checks, slit-lamp examination, fundus photography, and, in some models, optical coherence tomography (OCT). Some FEMUs provide dispensing of glasses, medications, and referrals for subspecialty or surgical care.

- Settings and Communities Served: Rural towns, low-income urban neighborhoods, Indigenous communities, senior living facilities, and areas without fixed eye care infrastructure.

- Strengths: High diagnostic capability in a single setting, earlier detection of chronic disease, reduced transportation burden, and ability to serve high-risk populations.

- Limitations: High costs for vehicles, equipment, staffing, fuel, and maintenance. Parking and permitting can be challenging, weather can disrupt operations, and units are not suitable for intraocular surgery.

Representative Case Examples

- University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC) eyeVan

- The Health Wagon [37]

3.1.2. Semi-Mobile Outreach Programs (SMOU)

- Description: Mobile outreach teams bring portable ophthalmic equipment to temporary clinic locations such as community centers, shelters, churches, FQHCs, and health fairs. Care is delivered inside the host site, not in a dedicated vehicle, and equipment is set up and packed down at each event.Unlike Fully Equipped Mobile Units (FEMUs), SMOUs do not contain built-in clinical space or permanently mounted diagnostic instruments; all equipment is transported and assembled at the outreach location.

- Services Provided: Vision screenings, auto/manual refraction, trial lens fitting, intraocular pressure measurement, screening for cataracts, glaucoma, and diabetic retinopathy, patient education, and written referrals for follow-up care.

- Settings and Communities Served: Urban and peri-urban communities, including individuals experiencing homelessness, migrant workers, and uninsured or underinsured populations.

- Strengths: Flexible and lower cost compared to FEMUs; can operate without on-site plumbing or electricity; easily deployable in a variety of settings; culturally adaptable; and supports community-based training for students and trainees.

- Limitations: Portable equipment limits diagnostic capacity; coordination and follow-up often occur off-site; documentation may be paper-based or fragmented; and operations frequently rely on volunteers and local partnerships.

Case Examples

- Eyes on Wheels [40]

- Indiana University Student Outreach Clinic Eye Program (IUSOC) [41]

- Kresge Eye Institute (KEI) Vision Detroit Project [42]

3.1.3. School-Based Vision Mobile Units (SBVMU)

- Description: School-Based Vision Mobile Units (SBVMUs) deliver eye care directly within school environments, either by bringing a mobile van onto school grounds or by setting up temporary exam stations inside school buildings. These programs focus primarily on children who fail school vision screenings and need full exams and eyeglasses. Unlike FEMUs, which operate as comprehensive mobile clinics for the general population, and unlike SMOUs, which serve varied community sites, SBVMUs are purpose-built around school workflows and pediatric needs, with services scheduled during the academic day.

- Services Provided: Repeat vision testing, cycloplegic refractions, on-site dispensing of prescription glasses, family education, and referrals to pediatric ophthalmology or optometry when needed.

- Settings and Communities Served: Elementary and middle schools in low-income districts, rural areas, or regions with historically low follow-up after school screenings.

- Strengths: Eliminate transportation barriers and the need for parental time off; support academic performance by addressing undiagnosed vision-related learning issues; and foster continuity by engaging school nurses, counselors, and support staff.

- Limitations: Require coordination with school administration; cannot serve students absent on clinic days; limited to non-complex conditions; and sustainability often depends on local funding or grants.

Case Examples

- Conexus Mobile Vision Clinic [44]

- Ypsilanti School-Based Eye Clinic [45]

- Additional case examples are: The Philadelphia Eagle Eye Mobile which provides optometric vision care to children who fail a vision screening performed by nurses at schools in low-income areas [46]. UCLA mobile provides vision screenings at public neighborhood elementary schools and community centers [39]. A nonprofit organization in Virginia provided in-school instrument-based screening and noncycloplegic examinations and refractions in elementary, middle, and high schools [47]

3.1.4. Hybrid Teleophthalmology Models (HTOU)

- Description: Hybrid Teleophthalmology Units (HTOUs) combine on-site imaging and basic screening with off-site diagnostic interpretation by eye specialists. Technicians or community health workers collect fundus photos or OCT images in the field, but diagnosis, grading, and management recommendations come from remote ophthalmologists or optometrists.Unlike SMOUs, HTOUs do not perform full clinical exams on-site, and they rely heavily on remote specialist input for clinical decision-making and follow-up plans. Unlike FEMUs, HTOUs do not operate a fully equipped vehicle; instead, they use portable devices paired with telemedicine platforms.

- Services Provided: High-resolution fundus photography; OCT where available; intraocular pressure assessment; asynchronous or synchronous specialist review; patient counseling; and follow-up navigation. Some programs incorporate digital tools to streamline triage and referral.

- Settings and Communities Served: Remote Indigenous communities, geographically isolated health centers, primary care clinics, and urban neighborhoods with limited in-person specialist access.

- Strengths: Extends specialist capacity across distances; supports early detection and triage with minimal on-site resources; scalable with lower long-term cost per patient; and aligns well with public health initiatives.

- Limitations: Requires reliable broadband connectivity and digital infrastructure; technicians need training for imaging and software use; asynchronous review may introduce delays; and start-up costs may be prohibitive for smaller organizations.

Case Examples

- Columbia University Teleophthalmology Unit [48]

- British Columbia’s Diabetic Retinopathy Teleunits [49]

- Diabetic Retinopathy Screening Program—University of Pittsburgh Medical Center [50]

4. Discussion

4.1. Four Primary MEU Models Identified

4.2. Importance of Model Selection Adapted to Community Needs

- FEMUs are most appropriate when comprehensive exams and diagnostics are needed on-site.

- SMOUs are ideal for rapid deployment in partner settings such as clinics or shelters.

- SBVMUs are effective for providing care to children within school systems.

- HTOUs are best suited for situations requiring remote subspecialty input, where portable imaging can be paired with structured pathways for transmitting results and coordinating follow-up care.

4.3. Major Problems in MEU Programs Requiring Attention

4.4. Advice for Improvement of MEUs

4.5. Strategies to Improve Follow-Up, Care Continuity, and Future Directions for MEUs

4.6. Considerations for Mobile Eye Surgical Units (MESUs)

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MEU | Mobile Eye Units |

| FEMUS | Fully Equipped Mobile Units |

| SMOU | Semi-Mobile Outreach Units |

| SBVMU | School-Based Vision Mobile Units |

| HTOU | Hybrid Tele-Ophthalmology Units |

| OHSU | Oregon Health & Science University |

| EHR | Electronic Health Record |

| UPMC | University of Pittsburgh Medical Center |

| U | University |

| UCLA | University of California Los Angeles |

| IUSOC | Indiana University Student outreach Clinic Eye Program (IUSOC) |

| KEI | Kresge Eye Institute |

| eCSC | Effective Cataract Surgical Coverage |

| MESU | Mobile Eye Surgical Units |

Appendix A. U.S Residency Programs with Mobile Eye Units (MEUs)

| State | Name of the Program | MEU? | Link |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | U Alabama | No | |

| Arkansas | U Arkansas | Yes | https://news.uams.edu/2024/12/20/uams-govision-van-rolls-out-screens-first-patients/ (Accessed on 1 July 2025) |

| Arizona | U Arizona | No | |

| California | Stanford University | Yes | https://med.stanford.edu/ophthalmology/patient_care/tele-eyecare.html#remote_diabetic_eyecareprogram (Accessed on 1 July 2025) |

| U California-Irvine | Yes | https://ophthalmology.uci.edu/community/eye-mobile-children (Accessed on 1 July 2025) | |

| U California-LA | Yes | https://www.uclahealth.org/departments/eye/mobile-eye (Accessed on 1 July 2025) | |

| U California-LA/EyeSTAR | Yes | https://www.uclahealth.org/departments/eye/mobile-eye (Accessed on 1 July 2025) | |

| U California—San Diego | Yes | https://shileyeye.ucsd.edu/about-us/shiley-eyemobile (Accessed on 1 July 2025) | |

| U California—SF | Yes | https://ophthalmology.ucsf.edu/log-on-the-doctor-will-see-you-now/eyevan/ (Accessed on 1 July 2025) | |

| USC Roski Eye Institute | No | ||

| U California—Davis | No | ||

| Loma Linda University | No | ||

| CPMC-San Francisco | No | ||

| U Colorado | No | ||

| Yale New Heaven Medical Center | No | ||

| Georgetown U/Wash Hosp | No | ||

| Howard U-Wash, DC | No | ||

| Colorado | George Washington U | No | |

| Connecticut | U Miami/Bascom Palmer | Yes | https://med.miami.edu/about-us/community-outreach (Accessed on 1 July 2025) |

| District of Columbia | University of South Florida | No | |

| U Florida-Gainesville | Yes | Not available (Accessed on 1 July 2025) | |

| University of Florida College of Medicine-Jacksonville | No | ||

| Florida | Broward health | No | |

| Emory University | No | ||

| Med C Georgia | No | ||

| Loyola U/Hines VA Hosp | No | ||

| Cook county-Chicago | No | ||

| Georgia | University of Chicago | No | |

| Rush Medical Center Northwestern University | No | ||

| Illinois | Illinois Eye and Ear Infirmary | No | |

| Indiana University | No | ||

| U Iowa | No | ||

| U Kansas | No | ||

| U Kentucky | Yes | https://ukhealthcare.uky.edu/kentucky-childrens-hospital/services/mobile-clinic (Accessed on 1 July 2025) | |

| Indiana | U Louisville | No | |

| Iowa | LSU—Shreverport | No | |

| Kansas | LSU—New Orleans | No | |

| Kentucky | Tulane University | No | |

| Sinai Hospital—Baltimore | No | ||

| Louisiana | Wilmer-Johns Hopkins | No | |

| U Maryland | No | ||

| Tufts/New England Eye Center | No | ||

| Maryland | U Massachusetts Chan Medical School | No | |

| Harvard Medical School—Mass, Eye & Ear | No | ||

| Boston University | No | ||

| Massachusetts | Henry Ford Hospital-Detroit | No | |

| U Michigan | No | ||

| Beamount Health-Royal Oak | No | ||

| Beamount Health-Taylor | No | ||

| Michigan | Ascension Macomb-Oakland | No | |

| Kresge Eye Institute-Wayne State | No | ||

| U Minnesota-Minneapolis | No | ||

| Mayo Clinic | No | ||

| University of Mississippi | No | ||

| Washington University | No | ||

| Minnesota | St. Louis University | No | |

| U Missouri—Columbia | No | ||

| Mississippi | U Missouri—Kansas City | No | |

| Missouri | U Nebraska | No | |

| Dartmouth-Hitchcock | No | ||

| Rutgers New Jersey Medical School | No | ||

| Columbia U/Harkness | Yes | https://www.cuimc.columbia.edu/news/tele-ophthalmology-van-pioneers-blindness-prevention-effort#:~:text=Through%20the%20department’s%20new%20tele,macular%20degeneration%2C%20and%20diabetic%20retinopathy. (Accessed on 1 July 2025) | |

| Nebraska | NY Presb. Hosp-Weill MC/Cornell U | Yes | https://eye.weillcornell.org/education-training/residency-program/international-and-community-service (Accessed on 1 July 2025) |

| New Hampshire | University of Rochester Flaum Eye Institute | Yes | https://www.urmc.rochester.edu/eye-institute/healthy-eyes/mobileyes (Accessed on 1 July 2025) |

| New Jersey | BronxCare Health System | Yes | https://www.bronxcare.org/our-services/ophthalmology/ophthalmology-residency-program/community-service (Accessed on 1 July 2025) |

| New York | SUNY—Downstate | Yes | Not available (Accessed on 1 July 2025) |

| Albany Medical College | No | ||

| SUNY—Upstate (Syracuse) | No | ||

| SUNY—Buffalo | No | ||

| New York Eye & Ear Infirmary | No | ||

| Albert Einstein College of Medicine | No | ||

| Northwell/Hofstra—No—No website | No | ||

| Nassau University MC | No | ||

| New York Medical College | No | ||

| St. John’s Episcopal Hospital | No | ||

| SUNY—Stony Brook | No | ||

| NYU Grossman | No | ||

| NYMC at Jamaica Hospital | No | ||

| Duke University | Yes | https://dukeeyecenter.duke.edu/news/remote-diagnosis-becomes-reality-new-mobile-imaging-van (Accessed on 1 July 2025) | |

| U North Carolina | Yes | https://shorturl.at/eEC7s (Accessed on 1 July 2025) | |

| Wake Forest University | No | ||

| Cleveland Clinic-Cole Eye Institute | Yes | https://my.clevelandclinic.org/departments/eye/services/pediatric-ophthalmology#community-outreach-tab (Accessed on 1 July 2025) | |

| North Carolina | Ohio State university | Yes | https://medicine.osu.edu/departments/ophthalmology/community-and-global-outreach/teleophthalmology (Accessed on 1 July 2025) |

| Case Western Reserved University | No | ||

| Kettering Health Network | No | ||

| Ohio | Cincinnati University | No | |

| U Oklahoma | No | ||

| Oregon HSU (Casey Eye Institute Outreach) | Yes | https://www.ohsu.edu/casey-eye-institute/casey-community-outreach-program-0 (Accessed on 1 July 2025) | |

| U Pittsburgh | Yes | https://eyeandear.org/eyes-on-wheels/ (Accessed on 1 July 2025) | |

| Scheie Eye Institute/U Penn | Yes | https://www3.pennmedicine.org/departments-and-centers/ophthalmology/about-us/news/department-news/scheie-offers-free-diabetic-eye-screenings-to-community (Accessed on 1 July 2025) | |

| Oklahoma | Nazareth Hospital Ophthalmology Residency | No | |

| Oregon | Temple U—Philadephia | No | |

| Pennsylvania | Wills Eye Hospital | No | |

| Penn State U—Hershey | No | ||

| Geisinger MC | No | ||

| Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine | No | ||

| U Puerto Rico | No | ||

| Brown University | No | ||

| Med U South Carolina | No | ||

| U South Carolina | No | ||

| Puerto Rico | Vanderbilt University Medical Center | No | |

| Rhode Island | U Tennessee-Memphis | No | |

| South Carolina | U Texas-San Antonio | Yes | https://lsom.uthscsa.edu/ophthalmology/education/medical-student-education/opthalmology-interest-group/ (Accessed on 1 July 2025) |

| U Texas/Methodist—Galveston | No | ||

| Tennessee | UT Southwestern-Dallas | No | |

| U Texas-Houston | No | ||

| Texas | UT Austin Dell Medical School | No | |

| Texas A&M/Baylor Scott & White | No | ||

| Baylor College of Medicine/Cullen Eye Institute | No | ||

| Texas Tech University | No | ||

| U Utah | Yes | https://healthcare.utah.edu/moran/outreach/community-clinics/ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-MeUEqdgKcI (Accessed on 1 July 2025) | |

| Eastern Virginia MS | No | ||

| U Virginia | No | ||

| Virginia Commonwealth University | No | ||

| Utah | U Washington | No | |

| Virginia | West Virginia University Eye Institute | Yes | https://medicine.hsc.wvu.edu/eye/outreach/appalachian-vision-outreach-program-avop (Accessed on 1 July 2025) |

| Med C Wisconsin | No | ||

| U Wisconsin | No | ||

| Washington | |||

| West Virginia | |||

| Wisconsin |

Appendix B. Case Examples Illustrating Operational Characteristics of Mobile Eye Units (MEUs)

| Program Name | Affiliation | Model Type | Population Served | Services Provided | Equipment Used | Follow-Up Mechanism | Key Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Casey Eye Institute Outreach Bus | OHSU | FEMU | Underserved communities in Oregon and Pacific Northwest | Full eye exams, diabetic eye care, glaucoma screening, refractions, retinal imaging, referrals | Slit lamps, fundus cameras, autorefractors, indirect ophthalmoscopes, EHR access | On-site triage, referrals to OHSU or partners | Episodic care, sustainability, follow-up |

| UPMC eyeVan | UPMC | FEMU/SMOU | Low-income, underserved communities in Western PA | Eye-exams, retinal imaging, glasses, refraction, OCT, pressure checks | Phoropter, slit lamp, indirect ophthalmoscope, fundus camera, OCT, mobile internet | Patient navigators, scheduled follow-up at UPMC clinics | Sustainability, logistics, equipment maintenance |

| The Health Wagon | Independent/partnerships | FEMU/SMOU | Low-income, rural Appalachian populations | Primary care + vision screening, diabetic eye screening, cataract evals | Portable ophthalmic equipment | Occasional referrals, volunteer specialists | Episodic, continuity, volunteer-dependence |

| UCLA Mobile Eye Clinic (UMEC) | UCLA Stein Eye Institute | SMOU | Homeless, uninsured, low-income children and adults | Basic exams, refraction, glasses | Portable visual acuity charts, autorefractors | Referral for advanced care | Limited diagnostics, dependent on partnerships |

| Eyes on Wheels | UPMC Vision Institute | SMOU | Uninsured and underinsured in Western PA | Full eye exams, referrals, screenings | Portable slit lamps, autorefractors, VA charts, tonometers | UPMC referral pathways, case navigation | Volunteer reliance, patient follow-through |

| IUSOC Eye Program | Indiana U School of Medicine | SMOU | Uninsured urban residents | Eye exams, pressure checks, referrals | Slit lamps, autorefractors, VA charts | Referral to partner clinics | Limited clinic frequency, volunteer dependence |

| Vision Detroit Project | Kresge Eye Institute | SMOU | Underserved in Detroit (African American, immigrant) | Full eye exams, diabetic & glaucoma screening, glasses | Portable diagnostic equipment | Partner navigation, referrals for surgery | Funding, mobile logistics, patient mobility |

| Vision First | Cleveland Clinic Cole Eye Institute | SBVMC | Public school students in Cleveland | Vision screening, cycloplegic refraction, glasses, referrals | School-based van, slit lamps, indirect ophthalmoscopes | Coordinator + referral to peds ophth | Continuity, follow-up, parental consent |

| Conexus Mobile Vision Clinic | Conexus (nonprofit) | SBVMC | Students in underserved areas of Virginia | Full eye exams, glasses | Mobile clinic with comprehensive setup | School delivery + parent coordination | Scheduling, space, longitudinal care |

| Ypsilanti School-Based Eye Clinic | U Michigan Kellogg Eye Center | SBVMC | Low-income, minority students in Ypsilanti | Eye exams, pressure check, glasses | School-based equipment | School nurses + referrals | School calendar, sustainability |

| Columbia Teleophthalmology Unit | Columbia University Irving Medical Center | HTOU | Public housing residents, uninsured adults in NYC | Fundus photography, asynchronous image review, navigation | Non-mydriatic cameras, VA charts | Navigator follow-up + scheduling | Connectivity, image quality, coordination |

| British Columbia DR Teleunits | BC Provincial Health Services + Indigenous orgs | HTOU | Remote Indigenous communities | DR screening, image upload + asynchronous review | Fundus cameras, upload tech | Local provider reports + referrals | Infrastructure, cultural barriers |

| DRSP-UPMC | UPMC Vision Institute | HTOU | UPMC affiliated facilities and Indigen clinics | DR screening, image upload + asynchronous review | Fundus cameras, upload tech | Local provider reports + referrals | Infrastructure, no live interactions, system capacity |

References

- Berkowitz, S.T.; Finn, A.P.; Parikh, R.; Kuriyan, A.E.; Patel, S. Ophthalmology Workforce Projections in the United States, 2020 to 2035. Ophthalmology 2024, 131, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, P.W.; Ahluwalia, A.; Feng, H.; Adelman, R.A. National Trends in the United States Eye Care Workforce from 1995 to 2017. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 218, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, R.; Vajaranant, T.S.; Burkemper, B.; Wu, S.; Torres, M.; Hsu, C.; Choudhury, F.; McKean-Cowdin, R. Visual Impairment and Blindness in Adults in the United States: Demographic and Geographic Variations From 2015 to 2050. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016, 134, 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. World Report on Vision; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Burton, M.J.; Ramke, J.; Marques, A.P.; Bourne, R.R.A.; Congdon, N.; Jones, I.; Tong, B.A.M.A.; Arunga, S.; Bachani, D.; Bascaran, C.; et al. The Lancet Global Health Commission on Global Eye Health: Vision beyond 2020. Lancet Glob. Health 2021, 9, e489–e551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinmetz, J.D.; Bourne, R.R.A.; Briant, P.S.; Flaxman, S.R.; Taylor, H.R.B.; Jonas, J.B.; Abdoli, A.A.; Abrha, W.A.; Abualhasan, A.; Abu-Gharbieh, E.G.; et al. Causes of Blindness and Vision Impairment in 2020 and Trends over 30 Years, and Prevalence of Avoidable Blindness in Relation to VISION 2020: The Right to Sight: An Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet Glob. Health 2021, 9, e144–e160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woreta, F.A.; Gordon, L.K.; Knight, O.J.; Randolph, J.D.; Zebardast, N.; Pérez-González, C.E. Enhancing Diversity in the Ophthalmology Workforce. Ophthalmology 2022, 129, e127–e136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Randolph, J.D.; Zebardast, N.; Pérez-González, C.E. Improving Ophthalmic Workforce Diversity: A Call to Action. Ophthalmology 2022, 129, 1081–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andoh, J.E.; Ezekwesili, A.C.; Nwanyanwu, K.; Elam, A. Disparities in Eye Care Access and Utilization: A Narrative Review. Annu. Rev. Vis. Sci. 2023, 9, 15–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atta, S.; Zaheer, H.A.; Clinger, O.; Liu, P.J.; Waxman, E.L.; McGinnis-Thomas, D.; Sahel, J.-A.; Williams, A.M. Characteristics Associated with Barriers to Eye Care: A Cross-Sectional Survey at a Free Vision Screening Event. Ophthalmic Res. 2023, 66, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montazeri, F.; Sohn, A.; Radgoudarzi, N.; Emami-Naeini, P. Barriers to Health Care Access and Use among Racial and Ethnic Minorities with Noninfectious Uveitis. Ophthalmology 2025, 132, 692–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikolajczyk, B.; Greenberg, E.R.; Fuher, H.; Berres, M.; May, L.L.; Areaux, R.G. Follow-up Adherence and Barriers to Care for Pediatric Glaucomas at a Tertiary Care Center. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 221, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, E.M.; Ahluwalia, A.; Parikh, R.; Nwanyanwu, K. Ophthalmic Emergency Department Visits: Factors Associated With Loss to Follow-Up. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 222, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuldt, R.; Jinnett, K. Barriers Accessing Specialty Care in the United States: A Patient Perspective. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Lamoureux, E.L.; Chiang, P.-C.P.; Anuar, A.R.; Ding, J.; Wang, J.J.; Mitchell, P.; Tai, E.-S.; Wong, T.Y. Language Barrier and Its Relationship to Diabetes and Diabetic Retinopathy. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkitt, W.R. The Work of the Kenya Mobile Eye Unit with Clinical Observations on Some Common Eye Diseases. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 1968, 52, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenken, E. MOBILE EYE CARE UNIT. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1971, 85, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenken, E. Canada’s First Mobile Eye Care Unit. Eye Ear Nose Throat Mon. 1971, 50, 117–118. [Google Scholar]

- Yuki, K.; Nakazawa, T.; Kurosaka, D.; Yoshida, T.; Alfonso, E.; Lee, R.; Takano, S.; Tsubota, K. Role of the Vision Van, a Mobile Ophthalmic Outpatient Clinic, in the Great East Japan Earthquake. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2014, 8, 691–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, H.; Rezvan, F.; Yekta, A.; Hashemi, M.; Norouzirad, R.; Khabazkhoob, M. The Prevalence of Astigmatism and Its Determinants in a Rural Population of Iran: The “Nooravaran Salamat” Mobile Eye Clinic Experience. Middle East Afr. J. Ophthalmol. 2014, 21, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, J.F.; Wilson, R.; Cimino, H.C.; Patthoff, M.; Martin, D.F.; Traboulsi, E.I. The Use of a Mobile Van for School Vision Screening: Results of 63 841 Evaluations. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2016, 163, 108–114.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merali, H.; Morgan, J.; Uk, S.; Phlan, S.; Wang, L.; Korng, S. The Lake Clinic—Providing Primary Care to Isolated Floating Villages on the Tonle Sap Lake, Cambodia. Rural Remote Health 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munsell, M.; Frank, T. The Orbis Flying Eye Hospital. J. Perioper. Pract. 2006, 16, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangameswaran, R.; Verma, G.; Raghavan, N.; Joseph, J.; Sivaprakasam, M. Cataract Surgery in Mobile Eye Surgical Unit: Safe and Viable Alternative. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2016, 64, 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chheda, K.; Wu, R.; Zaback, T.; Brinks, M.V. Barriers to Eye Care among Participants of a Mobile Eye Clinic. Cogent Med. 2019, 6, 1650693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, N.; Miller, F.; Khanna, D. Barriers to Eye Care for Adults in the United States and Solutions for It: A Literature Review. Cureus 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, D.M. The Geographic Distribution of Eye Care Providers in the United States: Implications for a National Strategy to Improve Vision Health. Prev. Med. 2015, 73, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syed, S.T.; Gerber, B.S.; Sharp, L.K. Traveling Towards Disease: Transportation Barriers to Health Care Access. J. Community Health 2013, 38, 976–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, S.D.; Shoge, R.Y.; Ervin, A.M.; Contreras, M.; Harewood, J.; Aguwa, U.T.; Olivier, M.M.G. Improving Access to Eye Care. Ophthalmology 2022, 129, e114–e126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarnegar, A.; Cassidy, J.; Stone, A.; McGinnis-Thomas, D.; Wasser, L.M.; Sahel, J.-A.; Williams, A.M. Effect of a Patient Navigator Program to Address Barriers to Eye Care at an Academic Ophthalmology Practice. J. Acad. Ophthalmol. 2023, 15, e106–e111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, L.B. Eye Mobile Units and Their Effect on Access to Pediatric Eye Care. J. Pediatr. Ophthalmol. Strabismus 2024, 61, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, K.R.; Murthy, P.R.; Kapur, A.; Owens, D.R. Mobile Diabetes Eye Care: Experience in Developing Countries. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2012, 97, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Turner, A.; Tan, I.; Muir, J. Identifying and Assessing Strategies for Evaluating the Impact of Mobile Eye Health Units on Health Outcomes. Aust. J. Rural Health 2017, 25, 326–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malone, N.C.; Williams, M.M.; Fawzi, M.C.S.; Bennet, J.; Hill, C.; Katz, J.N.; Oriol, N.E. Mobile Health Clinics in the United States. Int. J. Equity Health 2020, 19, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinks, M.; Zaback, T.; Park, D.-W.; Joan, R.; Cramer, S.K.; Chiang, M.F. Community-Based Vision Health Screening with on-Site Definitive Exams: Design and Outcomes. Cogent Med. 2018, 5, 1560641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, O.; Chen, A.; Li, Y.; Bailey, S.; Hwang, T.S.; Lauer, A.K.; Chiang, M.F.; Huang, D. Prospective Evaluation of Optical Coherence Tomography for Disease Detection in the Casey Mobile Eye Clinic. Exp. Biol. Med. 2021, 246, 2214–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, T.; Gavaza, P.; Meade, P.; Adkins, D.M. Delivering Free Healthcare to Rural Central Appalachia Population: The Case of the Health Wagon. Rural Remote Health 2012, 12, 2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haronian, E.; Wheeler, N.C.; Lee, D.A. Prevalence of Eye Disorders among the Elderly in Los Angeles. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 1993, 17, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischbach, L.A.; Lee, D.A.; Englehardt, R.F.; Wheeler, N. The Prevalence of Ocular Disorders among Hispanic and Caucasian Children Screened by the UCLA Mobile Eye Clinic. J. Community Health 1993, 18, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.M.; Botsford, B.; Mortensen, P.; Park, D.; Waxman, E.L. Delivering Mobile Eye Care to Underserved Communities While Providing Training in Ophthalmology to Medical Students: Experience of the Guerrilla Eye Service. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2019, 13, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowe, L.W.; Scheive, M.; Tso, H.L.; Wurster, P.; Kalafatis, N.E.; Camp, D.A.; Thau, A.; Yung, C.W.R. A Seven-Year Analysis of the Role and Impact of a Free Community Eye Clinic. BMC Med. Educ. 2021, 21, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, A.; Richards, C.; Patel, V.; Syeda, S.; Guest, J.-M.; Freedman, R.L.; Hall, L.M.; Kim, C.; Sirajeldin, A.; Rodriguez, T.; et al. The Vision Detroit Project: Visual Burden, Barriers, and Access to Eye Care in an Urban Setting. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2022, 29, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traboulsi, E.I.; Cimino, H.; Mash, C.; Wilson, R.; Crowe, S.; Lewis, H. Vision First, a Program to Detect and Treat Eye Diseases in Young Children: The First Four Years. Trans. Am. Ophthalmol. Soc. 2008, 106, 179–185; discussion 185-186. [Google Scholar]

- Kruszewski, K.; May, C.; Silverstein, E. Evaluation of a Combined School-Based Vision Screening and Mobile Clinic Program. J. Am. Assoc. Pediatr. Ophthalmol. Strabismus 2023, 27, 91.e1–91.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killeen, O.J.; Zhou, Y.; Musch, D.C.; Woodward, M.; Newman-Casey, P.A.; Moroi, S.; Speck, N.; Mukhtar, A.; Dewey, C. Access to Eye Care and Prevalence of Refractive Error and Eye Conditions at a High School–Based Eye Clinic in Southeastern Michigan. J. Am. Assoc. Pediatr. Ophthalmol. Strabismus 2022, 26, 185.e1–185.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvi, R.A.; Justason, L.; Liotta, C.; Martinez-Helfman, S.; Dennis, K.; Croker, S.P.; Leiby, B.E.; Levin, A.V. The Eagles Eye Mobile: Assessing Its Ability to Deliver Eye Care in a High-Risk Community. J. Pediatr. Ophthalmol. Strabismus 2015, 52, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.H.; Hong, J.D.; Suh, S.; Menezes, C.R.; Walker, K.R.; Bui, J.; Storch, A.; Torres, D.; Espinoza, J.; Shahraki, K.; et al. Exploring Pediatric Vision Care: Insights from Five Years of Referral Cases in the UCI Eye Mobile and Implications of COVID-19. J. Pediatr. Ophthalmol. Strabismus 2024, 61, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Aswad, L.A.; Elgin, C.Y.; Patel, V.; Popplewell, D.; Gopal, K.; Gong, D.; Thomas, Z.; Joiner, D.; Chu, C.-K.; Walters, S.; et al. Real-Time Mobile Teleophthalmology for the Detection of Eye Disease in Minorities and Low Socioeconomics At-Risk Populations. Asia Pac. J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 10, 461–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, A.J.; Martin, D.; Maberley, D.; Dawson, K.G.; Seccombe, D.W.; Beattie, J. Evaluation of a Mobile Diabetes Care Telemedicine Clinic Serving Aboriginal Communities in Northern British Columbia, Canada. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2004, 63 (Suppl. S2), 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonilla-Escobar, F.J.; Ghobrial, A.I.; Gallagher, D.S.; Eller, A.; Waxman, E.L. Comprehensive insights into a decade-long journey: The evolution, impact, and human factors of an asynchronous telemedicine program for diabetic retinopathy screening in Pennsylvania, United States. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0305586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Telemedicine Association. Ocular Telehealth SIG. Available online: https://www.americantelemed.org/community/ocular/ (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Mobile Health Map. Available online: https://www.mobilehealthmap.org/our-impact/ (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Preslan, M.W.; Novak, A. Baltimore Vision Screening Project. Ophthalmology 1998, 105, 150–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preslan, M.W.; Novak, A. Baltimore Vision Screening Project. Ophthalmology 1996, 103, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudie, L.I.; Guo, X.; Slavin, R.E.; Madden, N.; Wolf, R.; Owoeye, J.; Friedman, D.S.; Repka, M.X.; Collins, M.E. Baltimore Reading and Eye Disease Study: Vision Outcomes of School-Based Eye Care. Can. J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 57, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dotan, G.; Truong, B.; Snitzer, M.; McCauley, C.; Martinez-Helfman, S.; Maria, K.S.; Levin, A.V. Outcomes of an Inner-City Vision Outreach Program: Give Kids Sight Day. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015, 133, 527–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Citizens for Children and Youth. Envisioning Good Vision Care for Philadelphia Children; Public Citizens for Children and Youth: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2014. Available online: https://childrenfirstpa.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/PCCYEnvisioningGoodVisionCare.pdf (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Capó, H.; Edmond, J.C.; Alabiad, C.R.; Ross, A.G.; Williams, B.K.; Briceño, C.A. The Importance of Health Literacy in Addressing Eye Health and Eye Care Disparities. Ophthalmology 2022, 129, e137–e145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.M.; Sahel, J.-A. Addressing Social Determinants of Vision Health. Ophthalmol. Ther. 2022, 11, 1371–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ervin, A.-M.; Solomon, S.D.; Shoge, R.Y. Access to Eye Care in the United States: Evidence-Informed Decision-Making Is Key to Improving Access for Underserved Populations. Ophthalmology 2022, 129, 1079–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civerchia, L.; Ravindran, R.D.; Apoorvananda, S.W.; Ramakrishnan, R.; Balent, A.; Spencer, M.H.; Green, D. High-Volume Intraocular Lens Surgery in a Rural Eye Camp in India. Ophthalmic Surg. Lasers 1996, 27, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkataswamy, G. Massive Eye Relief Project in India. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1975, 79, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reilly, C.D.; Waller, S.G.; Flynn, W.J.; Montalvo, M.A.; Ward, J.B. U.S. Air Force Mobile Ophthalmic Surgery Team. Mil. Med. 2004, 169, 952–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, S.; Tadlock, M.D.; Douglas, T.; Provencher, M.; Ignacio, R.C. Integration of Surgical Residency Training With US Military Humanitarian Missions. J. Surg. Educ. 2015, 72, 898–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lansingh, V.C.; Resnikoff, S.; Tingley-Kelley, K.; Nano, M.E.; Martens, M.; Silva, J.C.; Duerksen, R.; Carter, M.J. Cataract Surgery Rates in Latin America: A Four-Year Longitudinal Study of 19 Countries. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2010, 17, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.; Vashist, P.; Sarath, S.; Gupta, N.; Senjam, S.S.; Shukla, P.; Grover, S.; Shamanna, B.R.; Vemparala, R.; Wadhwani, M.; et al. Effective Cataract Surgical Coverage in India: Evidence from 31 Districts. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2024, 72 (Suppl. S4), S650–S657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCormick, I.; Butcher, R.; Evans, J.R.; Mactaggart, I.Z.; Limburg, H.; Jolley, E.; Sapkota, Y.D.; Oye, J.E.; Mishra, S.K.; Bastawrous, A.; et al. Effective Cataract Surgical Coverage in Adults Aged 50 Years and Older: Estimates from Population-Based Surveys in 55 Countries. Lancet Glob. Health 2022, 10, e1744–e1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; Garner, P.; Floyd, K. Cost-Effectiveness of Public-Funded Options for Cataract Surgery in Mysore, India. Lancet 2000, 355, 180–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheck, L.; Riley, A.; Wilson, G.A. Is a Mobile Surgical Bus a Safe Setting for Cataract Surgery? A Four-year Retrospective Study of Intraoperative Complications. Clin. Experiment. Ophthalmol. 2012, 40, 330–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimensions | FEMU | SMOU | SBVMU | HTOU |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle/Structure | Large dedicated vehicle with built-in-clinic | Set-up inside the clinic; portable equipment packed in the van | Van or school-site temporary clinic | Portable imaging + telemedicine platform |

| Staffing | Ophthalmologist/Optometrist + techs + trainees | Ophthalmologist/Optometrist + techs + trainees | Pediatric ophthalmologist/optometrist + tech + school nurses/techs | Tech for imaging + remote ophthalmologist/optometrist |

| Diagnostic Capability | High (slit lamp, fundus camera, OCT) | Moderate (portable tools) | Moderate-high (pediatric focused equipment) | High for imaging; dependent on remote interpretation |

| Portability | Low | High | Moderate | High |

| Ideal Setting | Rural, remote or medically underserved areas needing comprehensive eye care | Urban or peri-urban outreach clinics | Schools, children’s programs | Remote communities; locations lacking specialist |

| Primary Strengths | Full clinical capacity; on-site diagnostics | Flexible, adaptable, cost-efficient compared to FEMU | Addresses pediatric disparities; integrates with schools | Extends subspecialty reach; efficient triage |

| Primary Limitations | Expensive; complex logistics; follow-up gaps; depend on academic partner and private funding most of the times | Limited diagnostics; follow-up gaps; depend on academic partner and private funding most of the times | Requires school coordination; depend on academic partners; follow-up gaps | Requires connectivity; may delay care if asynchronous; follow-up gaps |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Villabona-Martinez, V.; Zdunek, A.A.; Jiang, J.Y.; Sepulveda-Beltran, P.A.; Hobson, Z.A.; Waxman, E.L. Mobile Eye Units in the United States and Canada: A Narrative Review of Structures, Services and Challenges. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2026, 23, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010007

Villabona-Martinez V, Zdunek AA, Jiang JY, Sepulveda-Beltran PA, Hobson ZA, Waxman EL. Mobile Eye Units in the United States and Canada: A Narrative Review of Structures, Services and Challenges. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2026; 23(1):7. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010007

Chicago/Turabian StyleVillabona-Martinez, Valeria, Anna A. Zdunek, Jessica Y. Jiang, Paula A. Sepulveda-Beltran, Zeila A. Hobson, and Evan L. Waxman. 2026. "Mobile Eye Units in the United States and Canada: A Narrative Review of Structures, Services and Challenges" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 23, no. 1: 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010007

APA StyleVillabona-Martinez, V., Zdunek, A. A., Jiang, J. Y., Sepulveda-Beltran, P. A., Hobson, Z. A., & Waxman, E. L. (2026). Mobile Eye Units in the United States and Canada: A Narrative Review of Structures, Services and Challenges. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 23(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010007