Frequent Plastic Usage Behavior and Lack of Microplastic Awareness Correlates with Cognitive Decline: A Cross-Sectional Survey

Highlights

- Microplastics are persistent environmental contaminants that enter the human body primarily through ingestion, posing potential neurotoxic risks via oxidative stress and inflammation mechanisms.

- This study investigates the emerging intersection of environmental health and neurology by examining how daily plastic usage behaviors correlate with neurocognitive function in an adult population.

- Multivariate analysis indicates that high consumption of single-use plastics is significantly associated with a 41% increase regarding the risk of suspected cognitive impairment (OR = 1.409).

- The study identifies a critical gap in health literacy, where low awareness of microplastics correlates with higher consumption of single-use plastics, thus potentially increasing exposure to neurotoxic contaminants.

- Public health strategies must integrate environmental sustainability with neurological well-being, emphasizing reducing the consumption of single-use plastics as a preventative measure for cognitive health.

- Effective interventions require structural policy changes, such as phasing out virgin plastics and enforcing industry transparency, rather than relying solely on individual awareness, which was not found to be an independent predictor of cognitive status.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

3.2. Cognitive Function of Subjects

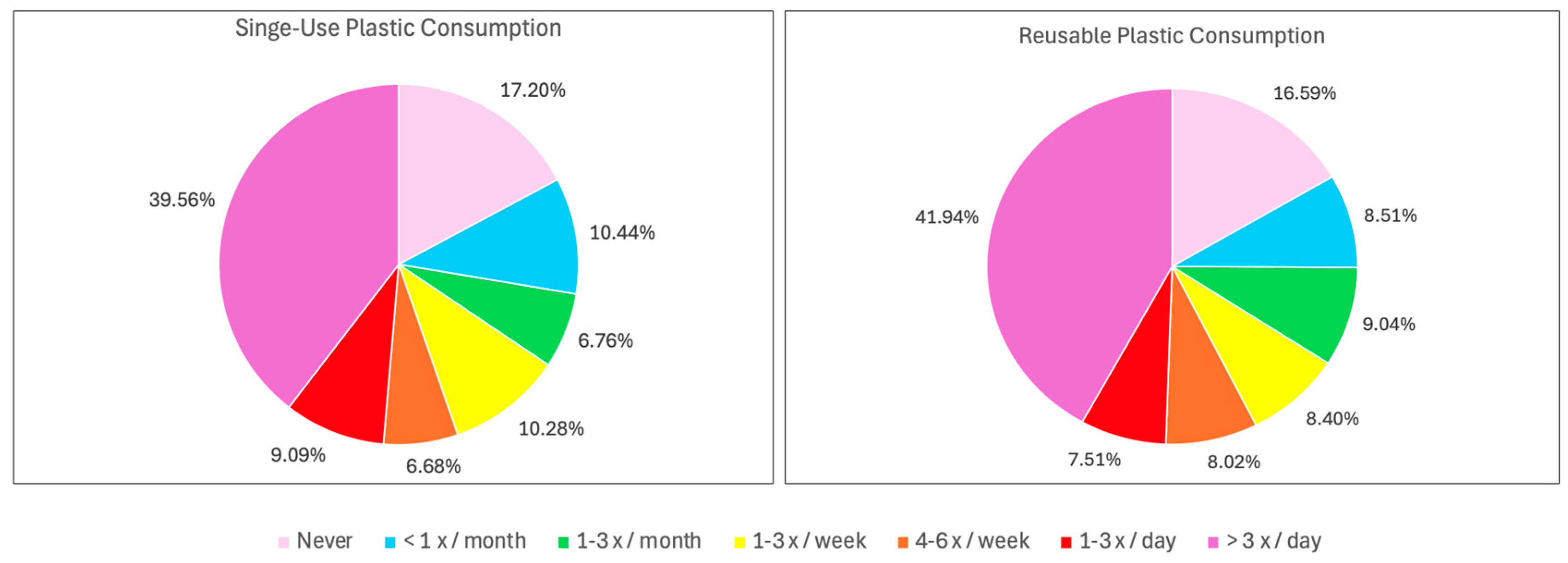

3.3. Plastic Usage Behavior

3.4. Microplastics Awareness and Knowledge

3.5. Attitudes Toward Microplastics

3.6. Risk Perception of Microplastics

3.7. Correlation of Awareness, Attitude, and Risk Perception with Plastic Usage Pattern

3.8. Cognitive Function of Subjects

3.9. Correlation of Cognitive Function and Plastic Usage Behavior

3.10. Multivariate Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Cognitive Function and Plastic Use Behavior

4.2. Awareness of Microplastics

4.3. Attitudes Towards Microplastics

4.4. Risk Perceptions of Microplastics

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abbasi, S.; Turner, A. Human exposure to microplastics: A study in Iran. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 403, 123799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akanyange, S.N.; Lyu, X.; Zhao, X.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Crittenden, J.C.; Anning, C.; Chen, T.; Jiang, T.; Zhao, H. Does microplastic really represent a threat? A review of the atmospheric contamination sources and potential impacts. Sci. Total. Environ. 2021, 777, 146020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, I.; Cheng, Q.; Ding, T.; Yiguang, Q.; Yuechao, Z.; Sun, H.; Peng, C.; Naz, I.; Li, J.; Liu, J. Micro-and nanoplastics in the environment: Occurrence, detection, characterization and toxicity-A critical review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 313, 127863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimba, C.G.; Faggio, C. Microplastics in the marine environment: Current trends in environmental pollution and mechanisms of toxicological profile. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2019, 68, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqua, A.; Hahladakis, J.N.; Al-Attiya, W.A.K.A. An overview of the environmental pollution and health effects associated with waste landfilling and open dumping. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2022, 29, 58514–58536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, G. Microplastics as vectors of contaminants. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 146, 921–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Yin, D.; Jia, Y.; Schiwy, S.; Legradi, J.; Yang, S.; Hollert, H. Enhanced uptake of BPA in the presence of nanoplastics can lead to neurotoxic effects in adult zebrafish. Sci. Total. Environ. 2017, 609, 1312–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, B.C.; Quinn, B. Microplastic Pollutants, 1st ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Collard, F.; Gilbert, B.; Compère, P.; Eppe, G.; Das, K.; Jauniaux, T.; Parmentire, E. Microplastics in livers of European anchovies (Engraulis encrasicolus, L.). Environ. Pollut. 2017, 229, 1000–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa Araújo, A.P.; Malafaia, G. Microplastic ingestion induces behavioral disorders in mice: A preliminary study on the trophic transfer effects via tadpoles and fish. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 401, 123263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Yan, Z.; Shen, R.; Huang, Y.; Ren, H.; Zhang, Y. Enhanced reproductive toxicities induced by phthalates contaminated microplastics in male mice (Mus musculus). J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 406, 124644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domenech, J.; Marcos, R. Pathways of human exposure to microplastics, and estimation of the total burden. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2021, 39, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prawiroharjo, P.; Zulys, A.; Fakhri, A.; Andini, A.R.; Putri, A.N.M.; Ikhromi, N.; Divind, E.; Gabrielle, A.; Martalia, V. Development and Validation Of A Questionnaire Assessing Plastic Use Patterns, Knowledge, And Attitudes Toward Microplastics In Relation To Cognitive Function In Indonesia. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanwani, R.; Danquah, M.O.; Butris, N.; Saripella, A.; Yan, E.; Kapoor, P.; Englesakis, M.; Tang-Wai, D.F.; Tartaglia, M.C.; He, D.; et al. Diagnostic accuracy of Ascertain Dementia 8-item Questionnaire by participant and informant—A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0291291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donohue, M.J.; Masura, J.; Gelatt, T.; Ream, R.; Baker, J.D.; Faulhaber, K.; Lerner, D.T. Evaluating exposure of northern fur seals, Callorhinus ursinus, to microplastic pollution through fecal analysis. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 138, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galgani, F.; Hanke, G.; Maes, T. Global Distribution, Composition and Abundance of Marine Litter. In Marine Anthropogenic Litter; Bergmann, M., Gutow, L., Klages, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 29–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, W. Micro (nano) plastic contaminations from soils to plants: Human food risks. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2021, 41, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iñiguez, M.E.; Conesa, J.A.; Fullana, A. Microplastics in Spanish Table Salt. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 8620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, C.-B.; Kang, H.-M.; Lee, M.-C.; Kim, D.-H.; Han, J.; Hwang, D.-S.; Souissi, S.; Lee, S.-J.; Shin, K.-H.; Park, H.G.; et al. Adverse effects of microplastics and oxidative stress-induced MAPK/Nrf2 pathway-mediated defense mechanisms in the marine copepod Paracyclopina nana. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 41323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyton, J.H.; Hall, J.E. Guyton and Hall Textbook of Medical Physiology, 13th ed.; Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Karami, A.; Golieskardi, A.; Keong Choo, C.; Larat, V.; Galloway, T.S.; Salamatinia, B. The presence of microplastics in commercial salts from different countries. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 46173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosuth, M.; Mason, S.A.; Wattenberg, E.V. Anthropogenic contamination of tap water, beer, and sea salt. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Ding, Y.; Cheng, X.; Sheng, D.; Xu, Z.; Rong, Q.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, H.; Ji, X.; Zhang, Y. Polyethylene microplastics affect the distribution of gut microbiota and inflammation development in mice. Chemosphere 2020, 244, 125492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Shi, M.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Cai, D.; Xiao, F. Keap1-Nrf2 pathway up regulation via hydrogen sulfide mitigates polystyrene microplastics induced hepatotoxic effects. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 402, 123933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhu, S.; Liu, Q.; Wei, J.; Jin, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L. Polystyrene microplastics cause cardiac fibrosis by activating Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway and promoting cardiomyocyte apoptosis in rats. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 265, 115025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liebezeit, G.; Liebezeit, E. Synthetic particles as contaminants in German beers. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2014, 31, 1574–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, S.; Qiu, R.; Hu, J.; Li, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, X.; Cao, C.; Shi, H.; Xie, B.; Wu, W.-M.; et al. Prevalence of microplastics in animal-based traditional medicinal materials: Widespread pollution in terrestrial environments. Sci. Total. Environ. 2020, 709, 136214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mak, C.W.; Ching-Fong Yeung, K.; Chan, K.M. Acute toxic effects of polyethylene microplastic on adult zebrafish. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 182, 109442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddela, N.R.; Kakarla, D.; Venkateswarlu, K.; Megharaj, M. Additives of plastics: Entry into the environment and potential risks to human and ecological health. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 348, 119364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nithin, A.; Sundaramanickam, A.; Surya, P.; Sathish, M.; Soundharapandiyan, B.; Balachandar, K. Microplastic contamination in salt pans and commercial salts-A baseline study on the salt pans of Marakkanam and Parangipettai, Tamil Nadu, India. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 165, 112101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Guevara, F.; Kutralam-Muniasamy, G.; Shruti, V.C. Critical review on microplastics in fecal matter: Research progress, analytical methods and future outlook. Sci. Total. Environ. 2021, 778, 146395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt, J.A.; Kozal, J.S.; Jayasundara, N.; Massarsky, A.; Trevisan, R.; Geitner, N.; Wiesner, M.; Levin, E.D.; Di Giulio, R.T. Uptake, tissue distribution, and toxicity of polystyrene nanoparticles in developing zebrafish (Danio rerio). Aquat. Toxicol. 2018, 194, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prüst, M.; Meijer, J.; Westerink, R.H.S. The plastic brain: Neurotoxicity of micro and nanoplastics. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2020, 17, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provencher, J.F.; Vermaire, J.C.; Avery-Gomm, S.; Braune, B.M.; Mallory, M.L. Garbage in guano? Microplastic debris found in faecal precursors of seabirds known to ingest plastics. Sci. Total. Environ. 2018, 644, 1477–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafiee, M.; Dargahi, L.; Eslami, A.; Beirami, E.; Jahangiri-Rad, M.; Sabour, S.; Amereh, F. Neurobehavioral assessment of rats exposed to pristine polystyrene nanoplastics upon oral exposure. Chemosphere 2018, 193, 745–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, C.; Parker, A.; Jefferson, B.; Cartmell, E. The Characterization of Feces and Urine: A Review of the Literature to Inform Advanced Treatment Technology. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 45, 1827–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Value (n = 562) |

|---|---|

| Age (median [min–max]) | 29 (19–69) |

| Gender (n [%]) | |

| Female | 351 (62.46) |

| Male | 211 (37.54) |

| Marital status (n [%]) | |

| Marry | 211 (37.54) |

| Not married | 323 (57.47) |

| Widow/Widower | 28 (4.98) |

| Expenses (n [%]) | |

| IDR 354,000 | 41 (7.30%) |

| IDR 354,000–532,000 | 25 (4.45%) |

| IDR 532,000–1,200,000 | 103 (18.33%) |

| IDR 1,200,000–6,000,000 | 293 (52.14%) |

| >IDR 6,000,000 | 100 (17.79%) |

| Education level | |

| Elementary school | 8 (1.42) |

| Junior high school | 12 (2.14) |

| Senior high school | 129 (22.95) |

| Diploma degree | 41 (7.30) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 312 (55.52) |

| Master’s degree | 52 (9.25) |

| Doctoral degree | 8 (1.42) |

| Characteristics | Single-Use | Reusable | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (n = 44) | Medium (n = 381) | High (n = 136) | p Value | Low (n = 182) | Medium (n = 193) | High (n = 267) | p Value | |

| Age | 0.001 * | 0.391 * | ||||||

| ≤30 (n = 330) | 15 (34.1%) | 233 (61.2%) | 82 (60.3%) | 100 (54.9%) | 152 (78.8%) | 78 (29.2%) | ||

| 31–49 (n = 183) | 19 (43.2%) | 118 (31.0%) | 45 (33.1%) | 61 (33.5%) | 86 (44.6%) | 35 (13.1%) | ||

| ≥50 (n = 49) | 10 (22.7%) | 30 (7.9%) | 9 (6.6%) | 21 (11.5%) | 19 (9.8%) | 9 (3.4%) | ||

| Gender | 0.669 * | 0.184 * | ||||||

| Male (n = 211) | 19 (43.2%) | 139 (36.5%) | 52 (38.2%) | 71 (39.0%) | 102 (52.8%) | 37 (13.9%) | ||

| Female (n = 351) | 25 (56.8%) | 242 (63.5%) | 48 (35.3%) | 111 (61.0%) | 155 (80.3%) | 85 (31.8%) | ||

| Education Level | 0.001 * | 0.266 * | ||||||

| Low (n = 149) | 6 (13.6%) | 78 (20.5%) | 45 (33.1%) | 35 (19.2%) | 62 (32.1%) | 32 (12.0%) | ||

| High (n = 413) | 35 (79.5%) | 295 (77.4%) | 82 (60.3%) | 141 (77.5%) | 188 (97.4%) | 83 (31.1%) | ||

| Characteristics | Awareness and Knowledge | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good (n = 180) | Intermediate (n = 243) | Bad (n = 139) | ||

| Age (n [%]) | 0.007 * | |||

| ≤30 | 115 (63.89%) | 145 (59.67%) | 70 (50.35%) | |

| 31–49 | 56 (31.11%) | 80 (32.92%) | 47 (33.81%) | |

| ≥50 | 9 (0.05%) | 18 (7.40%) | 22 (15.82%) | |

| Gender (n [%]) | 0.004 * | |||

| Male | 97 (53.8%) | 154 (63.3%) | 100 (71.9%) | |

| Female | 83 (46.11%) | 89 (36.6%) | 39 (28.0%) | |

| Education level (n [%]) | 0.027 * | |||

| Low (n = 149) | 45 (25.0%) | 56 (23.0%) | 48 (34.5%) | |

| High (n = 413) | 135 (75.0%) | 187 (77.0%) | 91 (65.4%) | |

| Characteristics | Attitude Toward of Microplastics | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good (n = 271) | Intermediate (n = 176) | Bad (n = 115) | ||

| Age (n [%]) | 0.037 * | |||

| ≤30 (n = 330) | 156 (57.56%) | 115 (65.34%) | 59 (51.30%) | |

| 31–49 (n = 183) | 94 (34.68%) | 50 (28.40%) | 39 (17.78%) | |

| ≥50 (n = 49) | 21 (7.74%) | 11 (6.25%) | 17 (14.78%) | |

| Gender (n [%]) | 0.360 | |||

| Male (n = 211) | 162 (59.77%) | 117 (66.47%) | 72 (62.60%) | |

| Female (n = 351) | 108 (39.85%) | 59 (33.52%) | 43 (37.39%) | |

| Education level (n [%]) | <0.001 * | |||

| Low (n = 149) | 88 (32.47%) | 23 (13.06%) | 38 (33.04%) | |

| High (n = 413) | 183 (67.52%) | 153 (86.93%) | 77 (66.95%) | |

| Characteristics | Risk Perception of Microplastic | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High (n = 160) | Intermediate (n = 202) | Low (n = 200) | ||

| Age (n [%]) | 0.344 | |||

| ≤30 (n = 330) | 91 (56.87) | 118 (58.41) | 121 (60.5) | |

| 31–49 (n = 183) | 59 (36.87) | 67 (33.16) | 57 (28.5) | |

| ≥50 (n = 49) | 10 (6.25) | 17 (8.41%) | 22 (11) | |

| Gender (n [%]) | 0.289 | |||

| Male (n = 211) | 54 (25.59) | 118 (43.8%) | 127 (63.5) | |

| Female (n = 351) | 106 (30.20) | 84 (42.2%) | 73 (36.5) | |

| Education level (n [%]) | 0.184 | |||

| Low (n = 149) | 33 (20.62) | 62 (30.69) | 54 (27.0%) | |

| High (n = 413) | 127 (79.37) | 140 (69.30) | 146 (73%) | |

| Variable | Single-Use Plastic (p-Value) | Reusable Plastic (p-Value) |

|---|---|---|

| Awareness and knowledge | 0.205 | 0.044 * |

| Attitude | 0.561 | 0.768 |

| Risk perception | 0.576 | 0.329 |

| Characteristics | Cognitive Function | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal (AD-8 0–1) (n = 313) | Cognitive Impairment (AD-8 ≥ 2) (n = 248) | ||

| Age (median [min–max]) | 24 (19-54) | 31 (23-69) | <0.001 * |

| Gender (n [%]) | 0.945 ** | ||

| Male (n = 211) | 130 (41.7%) | 81 (32.4%) | |

| Female (n = 351) | 182 (58.3%) | 169 (67.6%) | |

| Education level (n [%]) | 0.008 ** | ||

| Low (n = 149) | 65 (20.8%) | 84 (33.6%) | |

| High (n = 413) | 247 (79.2%) | 166 (66.4%) | |

| Plastic Usage Pattern | Cognitive Function | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal (AD-8 0–1) (n = 313) | Cognitive Decline (AD-8 ≥ 2) (n = 248) | |||

| Single use plastic | Low (n = 44) | 32 (5.7%) | 12 (12.2%) | 0.032 * |

| Medium (n = 381) | 208 (37.1%) | 173 (30.8%) | ||

| High (n = 136) | 73 (13.0%) | 63 (11.2%) | ||

| Reusable use plastic | Low (n = 182) | 60 (19.2%) | 42 (16.8%) | 0.605 |

| Medium (n = 193) | 104 (33.3%) | 89 (35.6%) | ||

| High (n = 267) | 148 (47.4%) | 119 (47.6%) | ||

| Psychosocial Domains | Cognitive Function | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal (AD-8 0–1) (n = 313) | Cognitive Decline (AD-8 ≥ 2) (n = 248) | |||

| Awareness and knowledge | Low (n = 44) | 11 | 33 | 0.014 * |

| Medium (n = 381) | 212 | 169 | ||

| High (n = 136) | 68 | 68 | ||

| Attitude | Low (n = 182) | 95 | 87 | 0.110 |

| Medium (n = 193) | 82 | 111 | ||

| High (n = 267) | 136 | 131 | ||

| Risk perception | Low (n = 200) | 102 | 98 | 0.065 * |

| Medium (n = 202) | 110 | 92 | ||

| High (n = 160) | 101 | 59 | ||

| Variables | B | S.E | Wald | p-Value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.303 | 0.139 | 4.722 | 0.030 * | 0.562–0.971 |

| Education level | −0.205 | 0.081 | 6.456 | 0.011 * | 0.695–0.954 |

| Single-use plastic usage | 0.343 | 0.159 | 4.658 | 0.031 * | 1.032–1.924 |

| Awareness and knowledge of Microplastics | 0.310 | 0.089 | 0.122 | 0.727 | 0.867–1.228 |

| Attitude toward microplastics | −0.035 | 0.034 | 1.104 | 0.293 | 0.904–1.031 |

| Risk perception of microplastic | 0.005 | 0.023 | 0.039 | 0.843 | 0.904–1.031 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Prawiroharjo, P.; Putri, A.N.M.; Ikhromi, N.; Fakhri, A.; Divina, E.; Permata, R.; Gabrielle, A.; Martalia, V.; Zulys, A. Frequent Plastic Usage Behavior and Lack of Microplastic Awareness Correlates with Cognitive Decline: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2026, 23, 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010067

Prawiroharjo P, Putri ANM, Ikhromi N, Fakhri A, Divina E, Permata R, Gabrielle A, Martalia V, Zulys A. Frequent Plastic Usage Behavior and Lack of Microplastic Awareness Correlates with Cognitive Decline: A Cross-Sectional Survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2026; 23(1):67. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010067

Chicago/Turabian StylePrawiroharjo, Pukovisa, Anyelir Nielya Mutiara Putri, Noryanto Ikhromi, Aldithya Fakhri, Elizabeth Divina, Rani Permata, Aileen Gabrielle, Violine Martalia, and Agustyno Zulys. 2026. "Frequent Plastic Usage Behavior and Lack of Microplastic Awareness Correlates with Cognitive Decline: A Cross-Sectional Survey" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 23, no. 1: 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010067

APA StylePrawiroharjo, P., Putri, A. N. M., Ikhromi, N., Fakhri, A., Divina, E., Permata, R., Gabrielle, A., Martalia, V., & Zulys, A. (2026). Frequent Plastic Usage Behavior and Lack of Microplastic Awareness Correlates with Cognitive Decline: A Cross-Sectional Survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 23(1), 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010067