Venous Thromboembolism Risk Assessment and Prophylaxis in Trauma Patients

Highlights

- Venous thromboembolism (VTE) constitutes a significant cause of preventable morbidity and mortality among trauma patients globally.

- Standardized risk assessment scales are essential tools for identifying high-risk trauma patients who require VTE prophylaxis.

- This study demonstrates that using specific risk assessment scales can reduce the incidence of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism in trauma care settings.

- Preventing hospital-acquired VTE in trauma patients significantly reduces healthcare expenses and long-term complications.

- Practitioners are advised to consistently utilize validated risk assessment scales to inform clinical decision-making concerning VTE prophylaxis within trauma departments.

- Hospitals and policymakers should require VTE risk stratification protocols as a standard quality indicator for trauma care.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Objective

2.2. Study Design and Measurements

2.3. VTE Prophylaxis Protocol

- -

- No active bleeding (stable hemoglobin for >12 h, no ongoing transfusion requirement)

- -

- No significant coagulopathy (INR < 1.5, PT or aPTT > 1.5 times normal, platelet count > 50,000/mm3)

- -

- Hemodynamic stability (mean arterial pressure > 65 mmHg without vasopressor support)

- -

- No high bleeding-risk conditions:

- -

- Large intracranial hemorrhage (>10 mL volume or >1 cm thickness)

- -

- High-grade solid organ injury with active extravasation or expansion

- -

- Recent surgery (<24 h) with active oozing

- -

- Uncorrected severe coagulopathy

- -

- Lower extremity symptoms: unilateral leg pain, swelling, warmth, erythema, or a palpable cord

- -

- Pulmonary symptoms: sudden dyspnea, chest pain, hemoptysis, tachypnea, or hypoxemia

- Ultrasound Surveillance:

- Examinations included:

- Veins examined:

- -

- Proximal: Common femoral, femoral, and popliteal veins

- -

- Distal: Posterior tibial, peroneal, and anterior tibial veins (if symptomatic)

- -

- DVT criteria: Noncompressible vein segment, visible intraluminal thrombus, absent or diminished color flow, and absent augmentation with distal compression

- -

- Quality control: Positive findings were confirmed by a board-certified vascular surgeon; clinical correlation was required for treatment decisions

- -

- Additional ultrasound examinations were performed for any patient with clinical suspicion of DVT, regardless of scheduled surveillance.

- PE Diagnosis:

- Bleeding Surveillance:

- Clinical assessment for signs of bleeding

- -

- Daily hemoglobin measurement

- -

- Platelet count every 3 days

- -

- For patients with traumatic brain injury: Repeat head CT within 24–48 h after starting anticoagulation, then as clinically indicated

2.4. Outcomes

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schultz, D.J.; Brasel, K.J.; Washington, L.; Goodman, L.R.; Quickel, R.R.; Lipchik, R.J.; Clever, T.; Weigelt, J.; Wisner, D.H.; Yukika, T.; et al. Incidence of asymptomatic pulmonary embolism in moderately to severely injured trauma patients. J. Trauma 2004, 56, 727–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, E.E.; Moore, H.B.; Kornblith, L.Z.; Neal, M.D.; Hoffman, M.; Mutch, N.J.; Sauaia, A. Trauma-induced coagulopathy. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2021, 7, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, Y.H.; Xu, M.Y. Trauma-induced pulmonary thromboembolism: What’s update? Chin. J. Traumatol. 2022, 25, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, M.K.; Garcia, D.A.; Wren, S.M.; Karanicolas, P.J.; Arcelus, J.I.; Heit, J.A.; Samama, C.M. Prevention of VTE in Nonorthopedic Surgical Patients. Chest 2012, 141, e227S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauritz, G.J.; Marcus, J.T.; Westerhof, N.; Postmus, P.E.; Vonk-Noordegraaf, A. Prolonged right ventricular post-systolic isovolumic period in pulmonary arterial hypertension is not a reflection of diastolic dysfunction. Heart 2011, 97, 473–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kakkos, S.K.; Gohel, M.; Baekgaard, N.; Bauersachs, R.; Bellmunt-Montoya, S.; Black, S.A.; Cate-Hoek, A.J.T.; Elalamy, I.; Enzmann, F.K.; Geroulakos, G.; et al. Editor’s Choice—European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) 2021 clinical practice guidelines on the management of venous thrombosis. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2021, 61, 9–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geerts, W.H.; Code, K.I.; Jay, R.M.; Chen, E.; Szalai, J.P. A prospective study of venous thromboembolism after major trauma. N. Engl. J. Med. 1994, 331, 1601–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Zhang, M.; Jin, J.; MacCormick, A.D. The effectiveness of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis interventions in trauma patients: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Injury 2023, 54, 111078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ley, E.J.; Brown, C.V.R.; Moore, E.E.; Sava, J.A.; Peck, K.; Ciesla, D.J.; Sperry, J.L.; Rizzo, A.G.; Rosen, N.G.; Brasel, K.J.; et al. Updated guidelines to reduce venous thromboembolism in trauma patients: A Western Trauma Association critical decisions algorithm. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2020, 89, 971–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenfield, L.J.; Proctor, M.C.; Rodriguez, J.L.; Luchette, F.A.; Cipolle, M.D.; Cho, J. Posttrauma thromboembolism prophylaxis. J. Trauma 1997, 42, 100–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sriprayoon, W.; Surakan, E.; Siriwanitchaphan, W. Prevalence of venous thromboembolism in trauma patients in a private tertiary care hospital. Bangk. Med. J. 2020, 16, 13–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulman, S.; Angerås, U.; Bergqvist, D.; Eriksson, B.; Lassen, M.R.; Fisher, W. Subcommittee on Control of Anticoagulation of the Scientific and Standardization Committee of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis. Definition of major bleeding in clinical investigations of antihemostatic medicinal products in surgical patients. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2010, 8, 202–204. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, R.K.; Arya, R. Venous thromboembolism: Racial and ethnic influences. Therapy 2008, 5, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Key, N.S.; Reiner, A.P. Genetic basis of ethnic disparities in VTE risk. Blood 2016, 127, 1844–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R.H.; Keenan, C.R. Effects of race and ethnicity on the incidence of venous thromboembolism. Thromb. Res. 2009, 123, S11–S17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berndtson, A.E.; Costantini, T.W.; Smith, A.M.; Kobayashi, L.; Coimbra, R. Does sex matter? Effects on venous thromboembolism risk in screened trauma patients. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016, 81, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paffrath, T.; Wafaisade, A.; Lefering, R.; Simanski, C.; Bouillon, B.; Spanholtz, T.; Wutzler, S.; Maegele, M. Venous thromboembolism after severe trauma: Incidence, risk factors and outcome. Injury 2010, 41, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lineberry, C.; Alexis, D.; Mukhi, A.; Duh, K.; Tharakan, M.; Vosswinkel, J.A.; Jawa, R.S. Venous thromboembolic disease in admitted blunt trauma patients: What matters? Thromb. J. 2023, 21, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nathens, A.B.; McMurray, M.K.; Cuschieri, J.; Durr, E.A.; Moore, E.E.; Bankey, P.E.; Maier, R.V. The practice of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in the major trauma patient. J. Trauma 2007, 62, 557–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufman, H.H.; Satterwhite, T.; McConnell, B.J.; Costin, B.; Borit, A.; Gould, L.; Pruessner, J.; Bernstein, D.; Gildenberg, P.L. Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism in head injured patients. Angiology 1983, 34, 627–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denson, K.; Morgan, D.; Cunningham, R.; Nigliazzo, A.; Brackett, D.; Lane, M.; Smith, B.; Albrecht, R. Incidence of venous thromboembolism in patients with traumatic brain injury. Am. J. Surg. 2007, 193, 380–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, J.P.; Mason, S.A.; Gomez, D.; Hoeft, C.; Subacius, H.; Xiong, W.; Neal, M.; Pirouzmand, F.; Nathens, A.B. Timing of pharmacologic venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in severe traumatic brain injury: A propensity-matched cohort study. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2016, 223, 621–631.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, R.M.; Larkin, M.B.; Szuflita, N.S.; Neal, C.J.; Tomlin, J.M.; Armonda, R.A.; Bailey, J.A.; Bell, R.S. Early venous thromboembolism chemoprophylaxis in combat-related penetrating brain injury. J. Neurosurg. 2017, 126, 1047–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schellenberg, M.; Inaba, K.; Biswas, S.; Heindel, P.; Benjamin, E.; Strumwasser, A.; Matsushima, K.; Lam, L.; Demetriades, D. When is it safe to start VTE prophylaxis after blunt solid organ injury? A prospective study from a Level I Trauma Center. World J. Surg. 2019, 43, 2797–2803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abelseth, G.; Buckley, R.E.; Pineo, G.E.; Hull, R.; Rose, M.S. Incidence of deep-vein thrombosis in patients with fractures of the lower extremity distal to the hip. J. Orthop. Trauma 1996, 10, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Kandemir, U.; Liu, P.; Zhang, H.; Wang, P.F.; Zhang, B.F.; Shang, K.; Fu, Y.-H.; Ke, C.; Zhuang, Y.; et al. Perioperative incidence and locations of deep vein thrombosis following specific isolated lower extremity fractures. Injury 2018, 49, 1353–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, L. Analysis of the occurrence of deep venous thrombosis in lower extremity fractures: A clinical study. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 34, 828–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niikura, T.; Sakai, Y.; Lee, S.Y.; Iwakura, T.; Kuroda, R.; Kurosaka, M. Rate of venous thromboembolism after complex lower-limb fracture surgery without pharmacological prophylaxis. J. Orthop. Surg. 2015, 23, 37–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

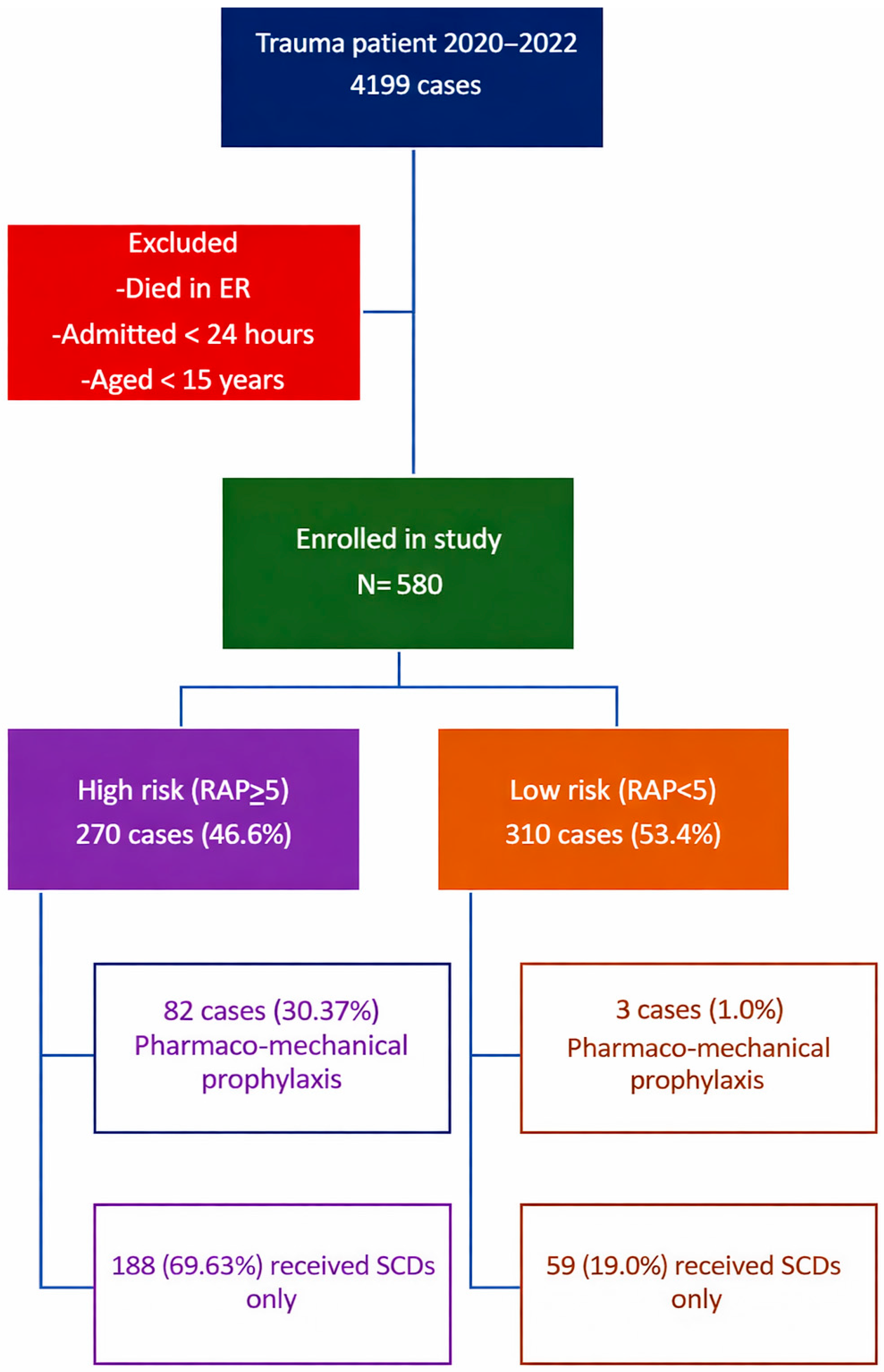

| Variables | High Risk (n = 270) | Low Risk (n = 310) | p-Value | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year), mean (SD) | 53.57 (19.89) | 42.86 (18.43) | <0.001 * | 1.030 (1.019–1.041) |

| Gender, male, n (%) | 195 (72.22) | 236 (76.13) | 0.283 | 0.813 (0.556–1.189) |

| ISS score, mean (SD) | 19.01 (11.51) | 10.73 (7.34) | <0.001 * | 1.090 (1.069–1.112) |

| Greenfield Risk Assessment Profiles | ||||

| Risk assessment score, mean (SD) | 8.88 (2.32) | 3.11 (1.60) | <0.001 * | MD 5.77 (5.33–6.21) ‡ § |

| Underlying conditions | ||||

| Obesity (BMI > 30 kg/m2), n (%) | 21 (7.78) | 12 (3.87) | 0.042 * | 2.088 (1.014–4.298) |

| Malignancy, n (%) | 14 (5.18) | 3 (0.97) | 0.003 * | 5.619 (1.588–19.88) |

| Abnormal coagulation factors at admission, n (%) | 60 (22.22) | 7 (2,26) | <0.001 * | 12.32 (5.518–27.50) |

| History of thromboembolism | 52 (19.26) | 4 (1.29) | <0.001 * | 17.97 (6.376–50.63) |

| Iatrogenic factors | ||||

| Femoral central venous catheter >24 h, n (%) | 4 (1.48) | 0 (0) | 0.046 * | ∞ (0.87–∞) ¶ |

| Four or more transfusions in 24 h, n (%) | 23 (8.51) | 1 (0.32) | <0.001 * | 28.74 (3.841–215.0) |

| Surgical procedure > 2 h, n (%) | 161 (59.62) | 38 (12.26) | <0.001 * | 10.80 (7.034–16.58) |

| Repair or ligation of major vascular injury (any named vessel), n (%) | 40 (14.81) | 4 (1.29) | <0.001 * | 13.32 (4.674–37.97) |

| Injury-related factors | ||||

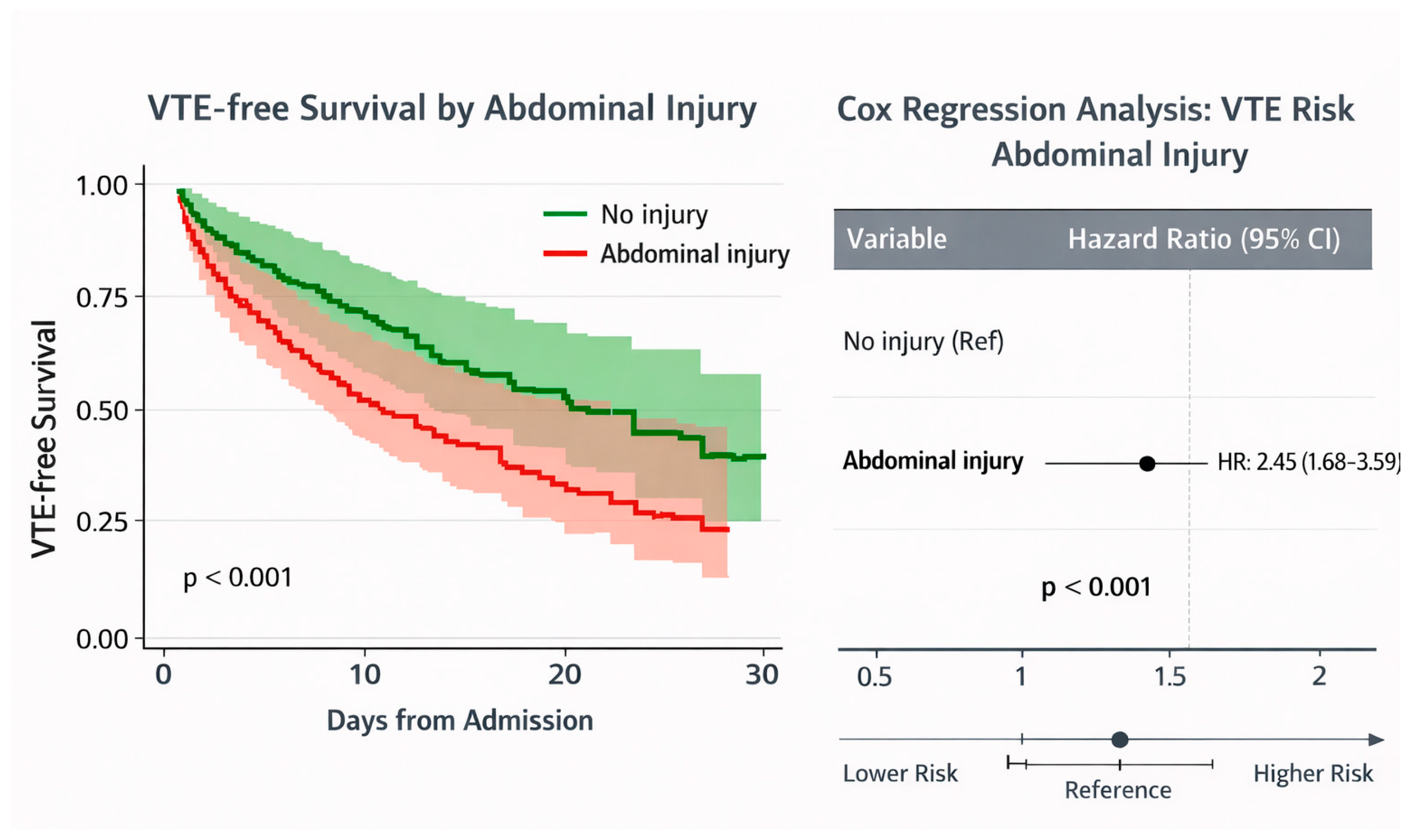

| AIS chest > 2, n (%) | 78 (28.29) | 34 (10.97) | <0.001 * | 3.280 (2.098–5.130) |

| AIS abdomen > 2, n (%) | 54 (20.00) | 15 (4.84) | <0.001 * | 4.899 (2.689–8.927) |

| AIS head > 2, n (%) | 105 (38.89) | 85 (27.42) | 0.010 * | 1.685 (1.187–2.391) |

| GCS score < 8 for >4 h, n (%) | 26 (9.63) | 4 (1.29) | <0.001 * | 8.134 (2.788–23.73) |

| Complex lower extremity fracture, n (%) | 67 (24.81) | 13 (4.19) | <0.001 * | 7.484 (4.020–13.93) |

| Pelvic fracture, n (%) | 22 (8.15) | 1 (0.32) | <0.001 * | 27.28 (3.618–205.7) |

| AGE, n (%) | <0.001 * | |||

| 40–59 | 101 (37.41) | 97 (31.29) | 2.322 (1.486–3.629) | |

| 60–74 | 56 (20.74) | 54 (17.42) | 2.314 (1.404–3.814) | |

| >75 | 49 (18.15) | 13 (4.19) | 8.410 (4.207–16.81) | |

| Variables | High Risk (n = 270) | Low Risk (n = 310) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Venous thromboembolism, n (%) | 8 (2.96) | 0 (0) | 0.002 * |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 7 (2.59) | ||

| Pulmonary embolism | 1 (0.37) | ||

| Major bleeding complication, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0.026 * | |

| Intracranial hemorrhage | 4 (1.48) | ||

| Minor bleeding complication, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0.037 * | |

| Gastrointestinal hemorrhage | 3 (1.11) | ||

| Hematuria | 3 (1.11) | ||

| Hematoma | 1 (0.37) | ||

| Bleeding per wound | 1 (0.37) |

| Case | Age | Gender | Injury | Risk Assessment Profile Score | Start Date of Anticoagulant After Trauma | VTE Event |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 67 | female | blunt traumatic jejunal injury grade, laceration wound at left knee, cerebral concussion | 10 | 7 | DVT |

| 2 | 33 | male | occipital condyle displacement, left SDH, complex maxillofacial injury | 10 | 4 | DVT |

| 3 | 64 | male | multiple rib fracture with left pneumothorax, pancreaticoduodenal injury, left subdural hemorrhage, C3–C4 fracture | 10 | - | DVT |

| 4 | 34 | male | posterior knee dislocation with popliteal artery injury, subarachnoid hemorrhage with subdural hemorrhage, C3–C5 spinous process fracture | 10 | 7 | DVT |

| 5 | 26 | male | right 6–10th rib fracture with hemothorax, liver laceration, right kidney Injury, left femoral shaft fracture and closed fracture subtrochanteric of right femur, sacral fracture (S1–S2), right Iliac crest fracture, traumatic brachial plexus injury lower arm type, traumatic SDH at falx cerebri, rhabdomyolysis | 15 | 7 | DVT |

| 6 | 68 | female | bilateral hemothorax, duodenal injury, fracture sacrum, iliac bone, posterior wall of right acetabulum, left pubic tubercle, right superior and inferior pubic rami | 15 | - | DVT |

| 7 | 40 | female | liver laceration, C7 spinal process fracture, comminuted fracture of greater wing of right sphenoid bone, right sphenozygomatic suture, right maxillary sinus, and right sphenoid sinus, closed fracture left distal end radius | 10 | - | DVT |

| 8 | 77 | male | open fracture right tibia, Cerebral concussion, close fracture right ulnar | 11 | 5 | PE |

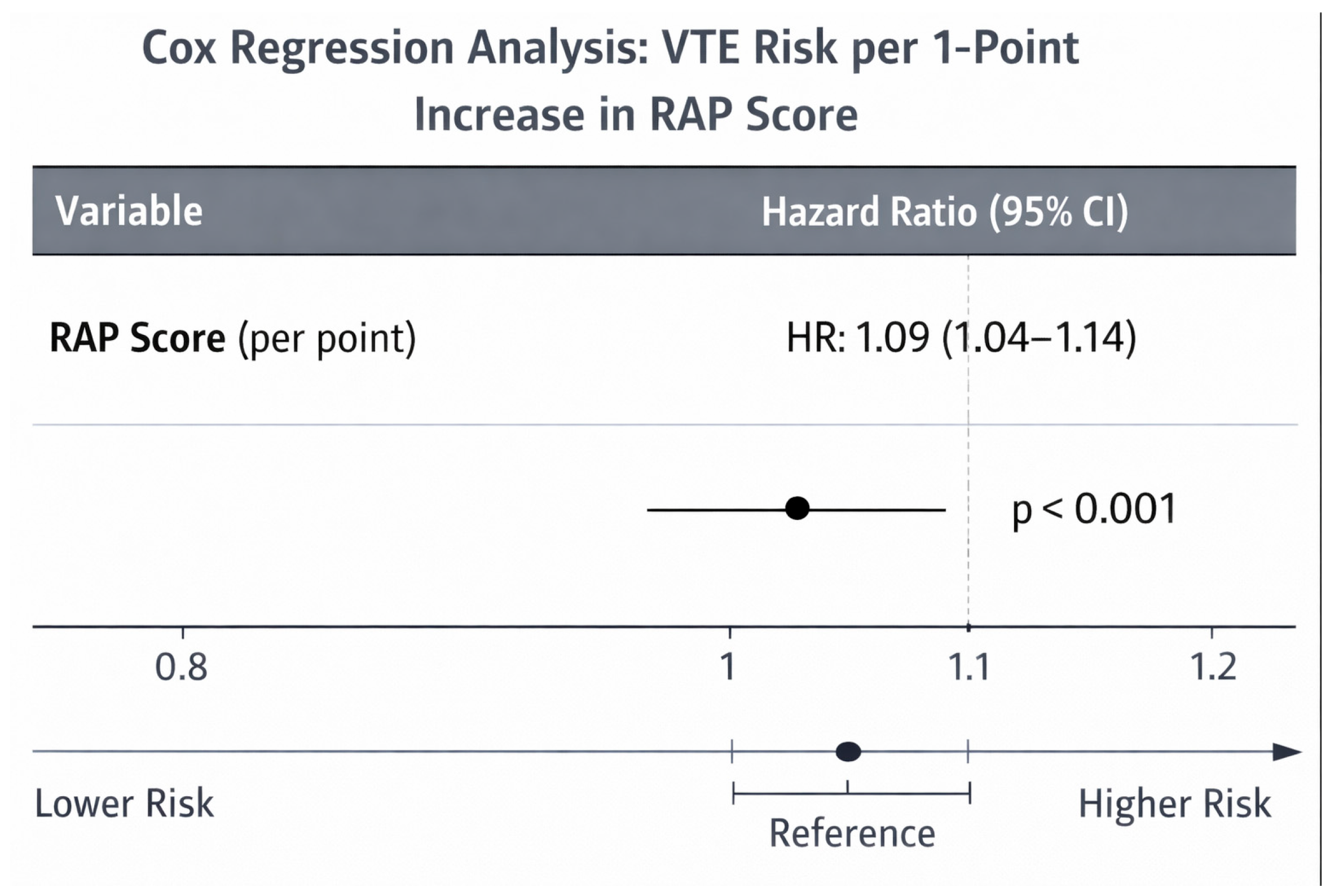

| Variable | Crude OR (Univariate) | p-Value | 95% CI | Adjusted OR (Multivariate) | p-Value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary multivariable model (n = 580, 8 VTE events) | ||||||

| RAP score (per point increase) | 1.671 | 1.313–2.126 | <0.001 * | 1.493 | 1.123–1.986 | 0.006 * |

| AIS abdomen (per severity level) | 1.678 | 1.197–2.354 | 0.003 * | 1.458 | 1.001–2.125 | 0.049 * |

| Pharmacologic prophylaxis | 8.312 | 1.857–37.22 | 0.006 * | 2.797 | 0.606–12.906 | 0.188 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tanmit, P.; Singthong, P.; Angkasith, P.; Teeratakulpisarn, P.; Wongkonkitsin, N.; Prasertcharoensuk, S.; Thanapaisal, C. Venous Thromboembolism Risk Assessment and Prophylaxis in Trauma Patients. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2026, 23, 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010059

Tanmit P, Singthong P, Angkasith P, Teeratakulpisarn P, Wongkonkitsin N, Prasertcharoensuk S, Thanapaisal C. Venous Thromboembolism Risk Assessment and Prophylaxis in Trauma Patients. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2026; 23(1):59. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010059

Chicago/Turabian StyleTanmit, Parichat, Patharat Singthong, Phati Angkasith, Panu Teeratakulpisarn, Narongchai Wongkonkitsin, Supatcha Prasertcharoensuk, and Chaiyut Thanapaisal. 2026. "Venous Thromboembolism Risk Assessment and Prophylaxis in Trauma Patients" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 23, no. 1: 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010059

APA StyleTanmit, P., Singthong, P., Angkasith, P., Teeratakulpisarn, P., Wongkonkitsin, N., Prasertcharoensuk, S., & Thanapaisal, C. (2026). Venous Thromboembolism Risk Assessment and Prophylaxis in Trauma Patients. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 23(1), 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010059