Ability to Detect Digital Risks: Effects of an Educational Intervention and Dementia Risk Level

Abstract

1. Introduction

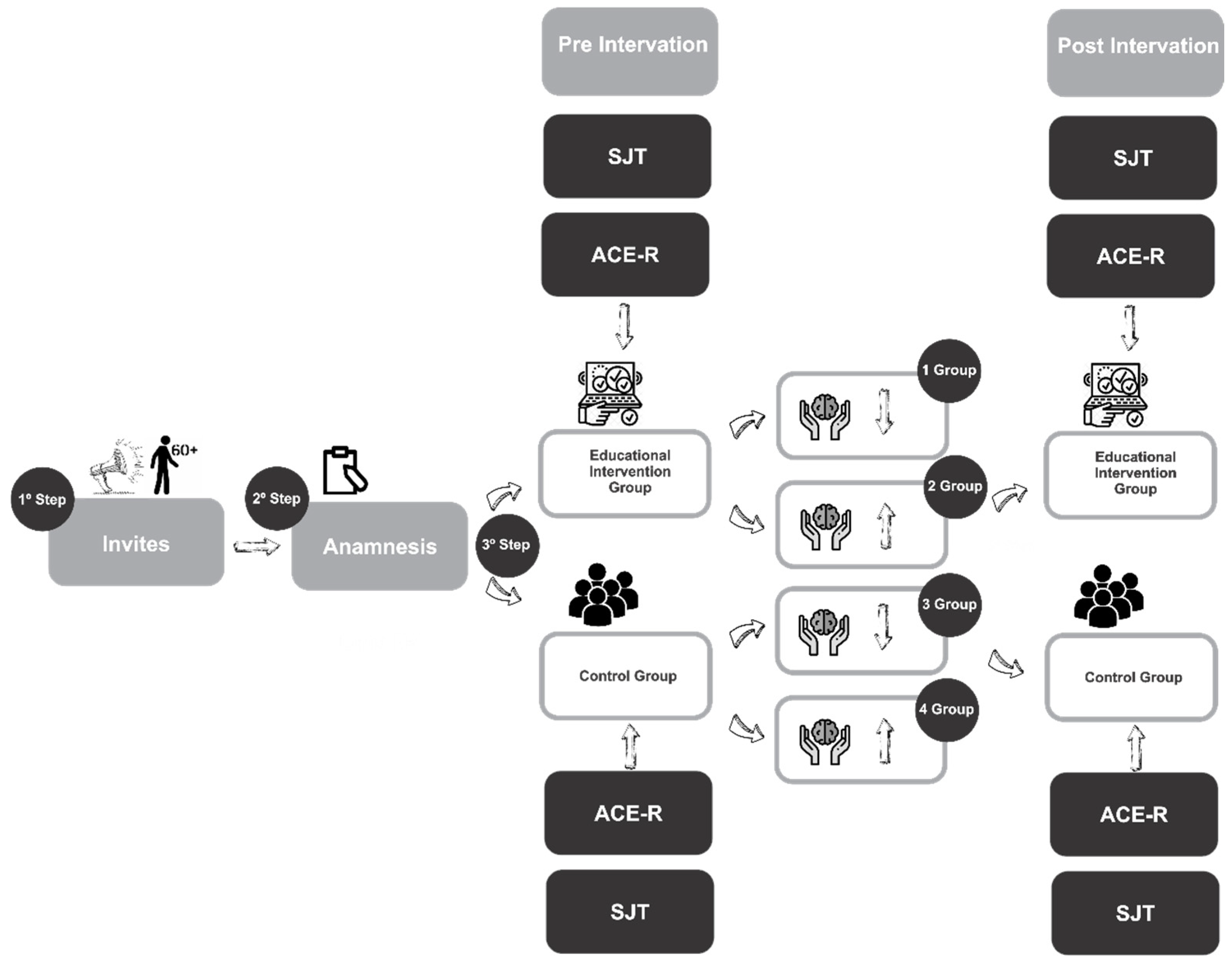

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Educational Intervention

2.2. Statistical Analysis

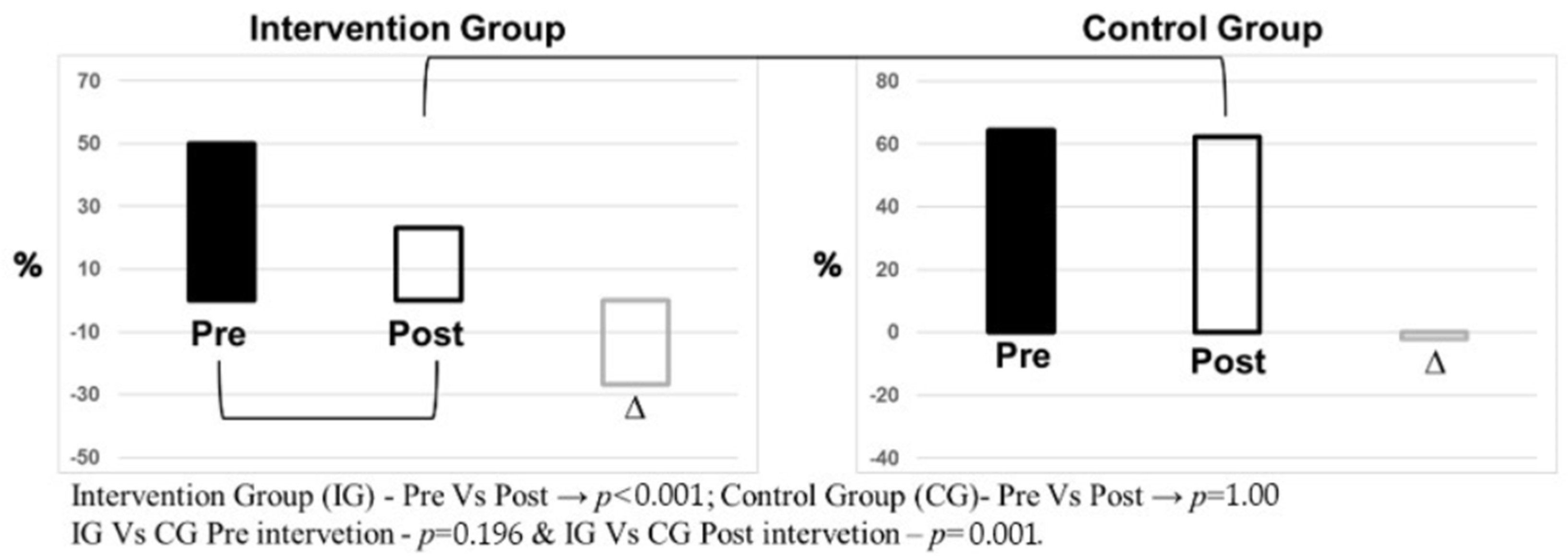

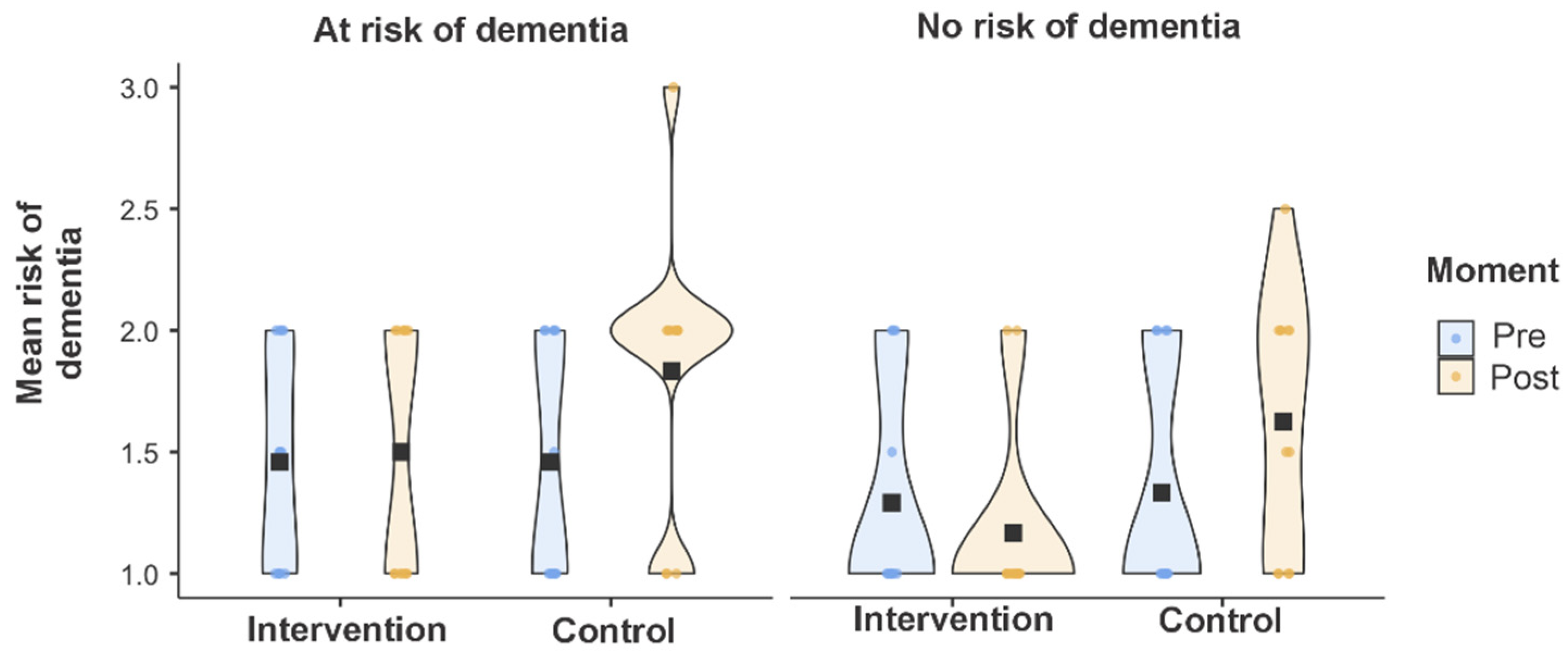

3. Results

Participants

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kemp, S.; Erades Pérez, N. Consumer fraud against older adults in digital society: Examining victimization and its impact. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, R.C.-F.; Zhou, J.H.-S.; Cao, Y.; Lo, K.; Ng, P.H.-F.; Shum, D.H.-K.; Wong, A.Y.-L. Nonpharmacological multimodal interventions for cognitive functions in older adults with mild cognitive impairment: Scoping review. JMIR Aging 2025, 8, e70291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clancy, U.; Makin, S.D.J.; McHutchison, C.A.; Cvoro, V.; Chappell, F.M.; Hernández, M.D.C.V.; Sakka, E.; Doubal, F.; Wardlaw, J.M. Impact of small vessel disease progression on long-term cognitive and functional changes after stroke. Neurology 2022, 98, e1459–e1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLiema, M.; Langton, L.; Brannock, M.D.; Preble, E. Aging and mass marketing fraud: Evidence on repeat victimization using perpetrator data. Innov. Aging 2023, 7 (Suppl. S1), 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebner, N.C.; Ellis, D.M.; Lin, T.; Rocha, H.A.; Yang, H.; Dommaraju, S.; Soliman, A.; Woodard, D.L.; Turner, G.R.; Spreng, R.N.; et al. Uncovering susceptibility risk to online deception in aging. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2020, 75, 522–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, O.E.-K.; Kim, D.-H. Bridging the digital divide for older adults via intergenerational mentor-up. Res. Soc. Work. Pract. 2019, 29, 786–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleti, T.; Figueiredo, B.; Reid, M.; Martin, D.M.; Sheahan, J.; Hjorth, L. Older adults’ digital competency, digital risk perceptions and frequency of everyday digital engagement. Inf. Technol. People 2025, 38, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhu, W.; Liang, N.; Zhang, C.; Pei, Y.; Wang, Q.; Li, S.; Shi, J. Reading activities compensate for low education-related cognitive deficits. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2022, 14, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, E.K.H.; Yeung, D.Y.-L. Reducing older people’s risk of fraud victimization through an anti-scam board game. J. Elder. Abus. Negl. 2023, 35, 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stara, V.; Felici, E.; Rossi, L.; Di Rosa, M.; Barbabella, F.; Rampioni, M.; Moșoi, A.A.; Kristaly, D.M.; Moraru, S.-A.; Paciaroni, L.; et al. A technology-based intervention to support older adults in living independently: Protocol for a cross-national feasibility pilot. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.; Wang, W.; Liu, J.; Tong, T. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014, 14, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, L.; Ye, L.; Tang, M. Effects of virtual reality-based interventions on cognitive function, emotional state, and quality of life in patients with mild cognitive impairment: A meta-analysis. Front. Neurol. 2025, 16, 1496382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunita, N.; Juhana, A.; Sari, I.P. Enhancing digital literacy in the elderly through media and technology to prevent hoaxes in Indonesia: A systematic literature review. Literasi J. Ilmu Pendidik. 2025, 16, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabermahani, F.; Almasi-Dooghaee, M.; Sheikhtaheri, A. Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment serious games: A systematic analysis in smartphone application markets. In dHealth 2022; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotyrba, M.; Habiballa, H.; Volná, E.; Jarušek, R.; Smolka, P.; Prášek, M.; Malina, M.; Jaremová, V.; Vantuch, J.; Bar, M.; et al. Expert system for neurocognitive rehabilitation based on the transfer of the ACE-R to CHC model factors. Mathematics 2022, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kepes, S.; Keener, S.K.; Lievens, F.; McDaniel, M.A. An integrative, systematic review of the situational judgment test literature. J. Manag. 2025, 51, 2278–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mioshi, E.; Dawson, K.; Mitchell, J.; Arnold, R.; Hodges, J.R. The Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination Revised (ACE-R): A brief cognitive test battery for dementia screening. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2006, 21, 1078–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral-Carvalho, V.; Bento Lima-Silva, T.; Inácio Mariano, L.; Cruz de Souza, L.; Cerqueira Guimarães, H.; Santoro Bahia, V.; Nitrini, R.; Tonidandel Barbosa, M.; Sanches Yassuda, M.; Caramelli, P. Improved accuracy of the Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination–Revised in the diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment, mild dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease and behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia using Mokken scale analysis. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2024, 100 (Suppl. S1), S45–S55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riina, V.; Stefano, K.; Yves, P. DigComp 2.2: The Digital Competence Framework for Citizens-With New Examples of Knowledge, Skills and Attitudes; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, P.; Hendrie, K.; Jester, D.J.; Dasarathy, D.; Lavretsky, H.; Ku, B.S.; Leutwyler, H.; Torous, J.; Jeste, D.V.; Tampi, R.R. Social connections as determinants of cognitive health and as targets for social interventions in persons with or at risk of Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders: A scoping review. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2024, 36, 92–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarus, S.; Tickner, P.; McGuire, M.R. Cybercrime against senior citizens: Exploring ageism, ideal victimhood, and the pivotal role of socioeconomics. Secur. J. 2025, 38, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaportzis, E.; Martin, M.; Gow, A.J. A tablet for healthy ageing: The effect of a tablet computer training intervention on cognitive abilities in older adults. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2017, 25, 841–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segarte, Y.L.R. The development of media and information skills in the elderly: A horizon under construction. Perspect. Austral 2023, 1, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Stefani, J.A.; Ribeiro, V.L. Gamificação e aprendizagem de cibersegurança em idosos: Estudo experimental. Educ. Tecnol. Lisb. 2025, 10, 67–82. [Google Scholar]

| Group | Study Condition | Dementia Risk Status (ACE-R) | n |

|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | Control | At risk (<78) | 16 |

| A2 | Control | No risk (≥78) | 29 |

| A3 | Intervention | At risk (<78) | 28 |

| A4 | Intervention | No risk (≥78) | 28 |

| Dimension | Pre-Intervention Situations | Post-Intervention Situations |

|---|---|---|

| Financial and/or Property-Related Abuse | Situation 1. You access a popular shopping website that is offering impressive discounts on high-value items. However, the only available payment method is via bank transfer or Pix, with no option for refund or return. What would you do in this situation? | Situation 1. You receive a WhatsApp message from a close relative, but the message is sent from an unfamiliar number. The person asks urgently for money to pay a bill, claiming they are using a temporary phone because their main device was stolen. How would you respond? |

| Situation 2. You receive a phone call from someone claiming to be a bank employee. They ask you to confirm your personal banking information, stating that it is necessary to avoid the imminent blocking of your account. How would you respond? | Situation 2. You receive the following email: “Hi! Find out how you can quadruple your investment in just one month! Click the link below to learn more about this innovative platform and start earning today! Don’t miss this chance!” www.superprofitableinvestment.com Click here. How would you react to this email? | |

| Situation 3. You receive a private message on Facebook from someone you don’t know. They introduce themselves as a representative of an organization that provides financial assistance to people in economic hardship. The message is well written and includes a professional-looking logo. To “activate” the assistance process, the person asks you to make a small bank transfer to cover what they describe as “necessary administrative fees.” How would you proceed? | Situation 3. You see an ad on Instagram offering a free online course with a certificate. When you click on the link, you are asked to provide personal information such as your ID number, tax ID, and credit card number to “validate” the certificate. How would you proceed? | |

| Digital Security | Situation 4. You received an email saying that your email account is about to be deactivated. The email asks you to click on a link to verify your account. How would you proceed? | Situation 4. You are using a public computer to access your email. When finishing, you realize you forgot to log out. How would you proceed? |

| Situation 5. You accessed a shopping website and noticed that the address starts with “http://”. How would you proceed? | Situation 5. When installing a new app on your phone, it asks for access to your camera, contacts, and location—even though these functions are not required to use the app. How would you proceed? | |

| Situation 6. You found a USB stick on the ground near your home and are curious about its contents. How would you proceed? | Situation 6. You realize that your social media account was accessed from an unknown location. How would you proceed? | |

| Digital Competency | Situation 7. Mrs. Cida is organizing recipes she found on the internet. She saved them with generic names like “file1.pdf” and “recipe2.docx”, and now she’s having trouble locating the ones she wants to use. How can Dona Cida better organize her files? | Situation 7. You are looking for information on how to lower blood pressure. You find two articles: one on a well-known cardiology website with scientific references and identified authors, and another on a personal blog with vague comments and promises of a “miracle cure.” Which article seems more reliable to use? |

| Situation 8. Mrs. Cida wants to access her banking app but realizes she uses the same password for various accounts, such as social media and email. She heard this could be risky. How can Dona Cida make her accounts more secure? | Situation 8. You joined a Facebook gardening group. During a conversation, some members made rude or disrespectful comments that disrupted the discussion. Question: How can you handle this situation to maintain good communication in the group? | |

| Situation 9. Mr. Antônio noticed that his computer freezes during a video call with his family. He wants to find a way to continue the conversation. What can Seu Antônio do to fix the problem? | Situation 9. You are preparing a presentation for your community group. During your research, you find free images you’d like to use. Some of them say “free for personal use only,” and others mention licenses. Question: How can you make sure you are using the images legally? | |

| Media Literacy | Situation 10. Mr. Antônio saw a graph in a newspaper article stating that energy consumption increased by 200%. The graph is not clear, making it hard to interpret the data. What can Seu Antônio do to correctly interpret the graph? | Situation 10. You watch a video on a social media platform showing a politician making a controversial statement that promotes racial and financial discrimination. How would you proceed? |

| Situation 11. Mrs. Ana wants to participate in an online forum about retirement. During the conversation, some participants begin to spread false information about changes in the pension system. How can Dona Ana contribute to a more productive discussion? | Situation 11. You see a post on social media claiming that a new virus is being spread through food sold in supermarkets. The post has already been shared thousands of times. How would you proceed? | |

| Situation 12. Mr Paulo is part of a Facebook group on local history. He saw another participant sharing a photo without mentioning the source. What can Seu Paulo do to encourage best practices in the group? | Situation 12. You receive a WhatsApp message saying that drinking hot water with lemon every morning cures serious illnesses. The message claims the information came from a famous doctor. How would you proceed? |

| Cognitive Domain | Pre-Intervention | Post-Intervention | Δ | p (Wilcoxon) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attention and Orientation | 16 [14;25;18] | 17 [15;18] | 0 [−1;1] | 0.736 |

| Memory | 19 [16;21] | 21 [18;24] | 3 [0;5] | <0.001 |

| Fluency | 8.5 [7;11] | 10 [8,25;11,75] | 1 [−1;3] | 0.032 |

| Language | 23 [21;25;25] | 25 [23;26] | 1 [−1;2] | 0.01 |

| Visuospatial | 13 [11;15] | 14 [12;16] | 0.5 [1;2] | 0.195 |

| Total Score | 79 [70.5;87.75] | 85.5 [79;91.75] | 4 [0.75;12.5] | <0.001 |

| Dimension | Control | Intervention | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0 [−1;0.0] | −1 [−1;0.0] | 0.292 |

| 0.0 [0.0;1] | 0.0 [−1;1] | 0.111 |

| 1 [−0.5;1] | 0 [−0.75;1] | 0.659 |

| 0.0 [−1;1] | −0.5 [−1;0.0] | 0.019 |

| D1 | D2 | D3 | D4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Intervention | |||||

| No Dementia Risk | Intervention | 2 [1;2.5] * | 1 [1;2] | 1 [0;2] | 2 [1;2] |

| Control | 3 [2;3] | 1 [1;2] | 1.5 [0;2] | 1 [0;2] | |

| With Dementia Risk | Intervention | 2 [2;3] * | 1 [1;2] | 1 [0;1] | 1 [0;2] |

| Control | 3 [2;3] | 1 [1;2] | 1 [0;2] | 1 [0;2] | |

| Post-Intervention | |||||

| No Dementia Risk | Intervention | 2 [1;2] * | 1 [1;2] | 2 [0;2] | 1 [1;2] |

| Control | 3 [2;3] | 2 [1;2] | 2 [1;2] | 1 [0;2] | |

| With Dementia Risk | Intervention | 2 [1;2] * | 1 [1;2] | 1 [1;2] | 1 [0;1] * |

| Control | 2 [2;3] | 2 [1;2] | 1 [1;2] | 1 [0;2] | |

| Change (Δ) | |||||

| No Dementia Risk | Intervention | −1 [−1;0] | 1 [1;2] | 2 [0;2] | 1 [1;2] |

| Control | 0 [−1;0] | 2 [1;2] | 2 [1;2] | 1 [0;2] | |

| With Dementia Risk | Intervention | / [00] | 1 [1;2] | 1 [1;2] | 1 [0;1] |

| Control | / [0;0] | 2 [1;2] | 1 [1;2] | 1 [0;2] | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ferreira, R.d.O.; Karnikowski, I.G.d.O.; Costa, E.N.; Oliveira, A.G.d.; Cruz, M.S.; Brandão, I.B.d.S.; Karnikowski, M.G.d.O. Ability to Detect Digital Risks: Effects of an Educational Intervention and Dementia Risk Level. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2026, 23, 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010058

Ferreira RdO, Karnikowski IGdO, Costa EN, Oliveira AGd, Cruz MS, Brandão IBdS, Karnikowski MGdO. Ability to Detect Digital Risks: Effects of an Educational Intervention and Dementia Risk Level. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2026; 23(1):58. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010058

Chicago/Turabian StyleFerreira, Ricardo de Oliveira, Isabella Gomes de Oliveira Karnikowski, Emmanuely Nunes Costa, Aline Gomes de Oliveira, Mariana Sodário Cruz, Iolanda Bezerra dos Santos Brandão, and Margô Gomes de Oliveira Karnikowski. 2026. "Ability to Detect Digital Risks: Effects of an Educational Intervention and Dementia Risk Level" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 23, no. 1: 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010058

APA StyleFerreira, R. d. O., Karnikowski, I. G. d. O., Costa, E. N., Oliveira, A. G. d., Cruz, M. S., Brandão, I. B. d. S., & Karnikowski, M. G. d. O. (2026). Ability to Detect Digital Risks: Effects of an Educational Intervention and Dementia Risk Level. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 23(1), 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010058