Validation of the Ambivalence and Uncertainty Scale

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Development of the Ambivalence and Uncertainty Scale (AUS)

- Experience of Ambivalence—the tendency to frequently experience contradictory emotions and thoughts.

- Ambivalence Intolerance—the discomfort associated with holding conflicting attitudes and the tendency to avoid or resolve ambivalence.

- Decision-Making Difficulties—the dispositional tendency to struggle with choices, particularly under conditions of uncertainty.

2.3. Validation Strategy

2.4. Additional Measures

2.4.1. Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms (PHQ-4)

2.4.2. Maslach Burnout Inventory—Human Services Survey for Medical Personnel (MBI-HSS (MP))

2.4.3. Sense of Coherence (SOC-3)

2.4.4. Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI-20)

2.4.5. Work-Family Conflict (WFC)/Family-Work Conflict (FWC)

2.4.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

| Variable | Category | n (%) | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 321 (25.6) | 2.19 | 0.55 |

| Female | 928 (74.1) | 2.24 | 58 | |

| Divers | 4 (0.3) | 2.40 | 0.82 | |

| Age | 18–30 years | 209 (16.7) | 2.40 | 0.58 |

| 31–40 years | 319 (25.5) | 2.28 | 0.58 | |

| 41–50 years | 271 (21.6) | 2.24 | 0.60 | |

| 51–60 years | 342 (27.3) | 2.01 | 0.53 | |

| >60 years | 112 (8.9) | 2.20 | 0.58 | |

| Professional group | Nursing staff | 419 (33.4) | 2.23 | 0.56 |

| Physicians | 201 (16.0) | 2.10 | 0.53 | |

| Medical-technical staff | 146 (11.7) | 2.32 | 0.56 | |

| Psychologists | 39 (3.1) | 2.17 | 0.56 | |

| Therapeutical professions | 35 (2.8) | 2.15 | 0.55 | |

| Chaplains | 49 (3.9) | 2.01 | 0.49 | |

| Students | 12 (1.0) | 2.60 | 0.69 | |

| Other professional groups | 352 (28.1) | 2.21 | 0.59 |

3.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

3.3. Measurement Invariance Across Gender and Age

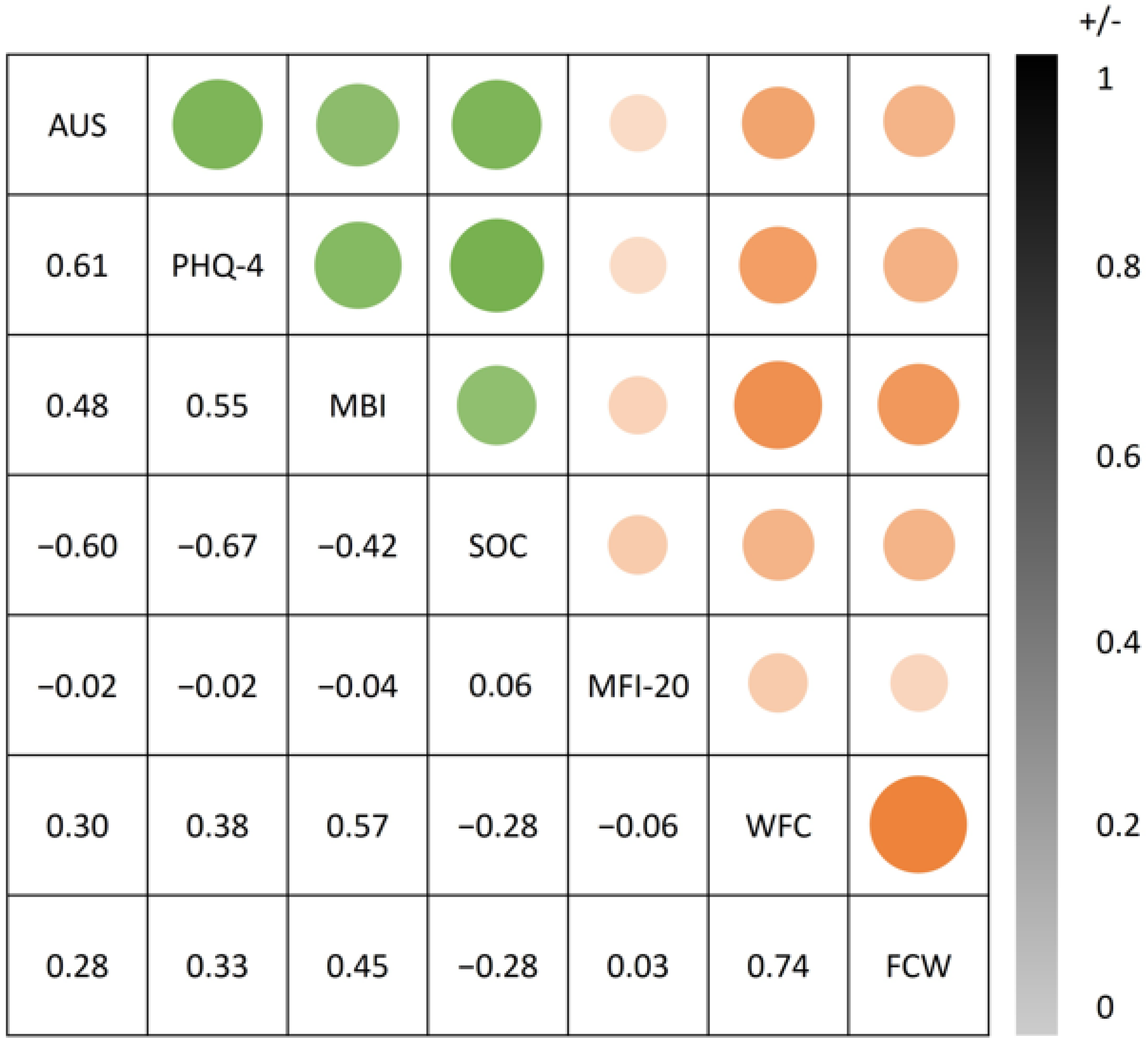

3.4. Convergent Validity

3.5. Divergent Validity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wen, J.; Zou, L.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, W.; Liu, Z.; Ma, Q.; Fei, Y.; Mao, J.; Fu, W. The relationship between personal-job fit and physical and mental health among medical staff during the two years after COVID-19 pandemic: Emotional labor and burnout as mediators. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 327, 416–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Han, P.; Zhuang, Y.; Jiang, J. The resilience of emergency and critical care nurses: A qualitative systematic review and meta-synthesis. Front Psychol. 2023, 14, 1226703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanzara, R.; Conti, C.; Rosa, I.; Pawłowski, T.; Malecka, M.; Rymaszewska, J.; Porcelli, P.; Stein, B.; Waller, C.; Müller, M.M.; et al. Changes in hospital staff’ mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: Longitudinal results from the international COPE-CORONA study. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0285296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghahramani, S.; Lankarani, K.B.; Yousefi, M.; Heydari, K.; Shahabi, S.; Azmand, S. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Burnout Among Healthcare Workers During COVID-19. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 758849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallgren, J.; Larsson, M.; Kjellén, M.; Lagerroth, D.; Bäckström, C. “Who will do it if I don’t?” Nurse anaesthetists’ experiences of working in the intensive care unit during the COVID-19 pandemic. Aust. Crit. Care 2022, 35, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M.M.; Zanna, M.P.; Griffin, D.W. Let’s not be indifferent about (attitudinal) ambivalence. In Attitude Strength: Antecedents and Consequences; Petty, R.E., Krosnick, J.A., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1995; pp. 361–386. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1995-98997-014 (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- van Harreveld, F.; Rutjens, B.T.; Rotteveel, M.; Nordgren, L.F.; Van Der Pligt, J. Ambivalence and decisional conflict as a cause of psychological discomfort: Feeling tense before jumping off the fence. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 45, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddock, S.A.; Weiler, L.M.; Trump, L.J.; Henry, K.L. The Efficacy of Internal Family Systems Therapy in the Treatment of Depression Among Female College Students: A Pilot Study. J. Marital. Fam. Ther. 2017, 43, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothman, N.B.; Pratt, M.G.; Rees, L.; Vogus, T.J. Understanding the dual nature of ambivalence: Why and when ambivalence leads to good and bad outcomes. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2017, 11, 33–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranowski, A.M.; Blank, R.; Maus, K.; Tüttenberg, S.C.; Matthias, J.K.; Culmann, A.C.; Radbruch, L.; Richter, C.; Geiser, F. ‘We are all in the same boat’: A qualitative cross-sectional analysis of COVID-19 pandemic imagery in scientific literature and its use for people working in the German healthcare sector. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1296613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priester, J.R.; Petty, R.E. The Gradual Threshold Model of Ambivalence: Relating the Positive and Negative Bases of Attitudes to Subjective Ambivalence. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 7, 431–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, A.I.; Tormala, Z.L. Valence Asymmetries in Attitude Ambivalence. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2017, 112, 555–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newby-Clark, I.R.; McGregor, I.; Zanna, M.P. Thinking and caring about cognitive inconsistency: When and for whom does attitudinal ambivalence feel uncomfortable? J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 82, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durso, G.R.O.; Briñol, P.; Petty, R.E. From Power to Inaction: Ambivalence Gives Pause to the Powerful. Psychol. Sci. 2016, 27, 1660–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demarree, K.G.; Briñ Ol, P.; Petty, R.E. Reducing Subjective Ambivalence by Creating Doubt: A Metacognitive Approach. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2015, 7, 731–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, I.K.; Novin, S.; van Harreveld, F.; Genschow, O. Benefits of being ambivalent: The relationship between trait ambivalence and attribution biases. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2021, 60, 570–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujikawa, H.; Aoki, T.; Ando, T.; Haruta, J. Associations of clinical context-specific ambiguity tolerance with burnout and work engagement among Japanese physicians: A nationwide cross-sectional study. BMC Med. Educ. 2024, 24, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedpuria, N.K.; Halim, T.; Kumar, H. Decision-Making and Personality Difficulties among College Students | Psychology and Education Journal. Psychol. Educ. J. 2021, 58. Available online: http://psychologyandeducation.net/pae/index.php/pae/article/view/5758 (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Mavroveli, S.; Mikolajczak, M.; Dåderman, A.M.; Petrides, K.V.; Farnia, F.; Nafukho, F.M. Predicting Career Decision-Making Difficulties: The Role of Trait Emotional Intelligence, Positive and Negative Emotions. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccon, C.; Moscardino, U. Friendship attachment style, intolerance of uncertainty, and psychological distress among unaccompanied immigrant minors in times of COVID-19. J. Adolesc. 2024, 96, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carleton, R.N.; Norton, M.A.P.J.; Asmundson, G.J.G. Fearing the unknown: A short version of the Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale. J. Anxiety Disord. 2007, 21, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuter, M.; Cooper, A.J.; Smillie, L.D.; Markett, S.; Montag, C. A new measure for the revised reinforcement sensitivity theory: Psychometric criteria and genetic validation. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Löwe, B.; Wahl, I.; Rose, M.; Spitzer, C.; Glaesmer, H.; Wingenfeld, K.; Schneider, A.; Brähler, E. A 4-item measure of depression and anxiety: Validation and standardization of the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4) in the general population. J. Affect. Disord. 2010, 122, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lheureux, F.; Truchot, D.; Borteyrou, X.; Rascle, N. The Maslach Burnout Inventory—Human Services Survey (MBI-HSS): Factor structure, wording effect and psychometric qualities of known problematic items. Trav. Hum. 2017, 80, 161–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, O.; Peck, M.N. A simplified way of measuring sense of coherence: Experiences from a population survey in Sweden. Eur. J. Public. Health 1995, 5, 56–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonovsky, A. Unraveling the Mystery of Health: How People Manage Stress and Stay Well; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz, R.; Krauss, O.; Hinz, A. Fatigue in the general population. Onkologie 2003, 26, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smets, E.M.A.; Garssen, B.; Bonke, B.; De Haes, J.C.J.M. The multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI) psychometric qualities of an instrument to assess fatigue. J. Psychosom. Res. 1995, 39, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netemeyer, R.G.; Boles, J.S.; McMurrian, R. Development and validation of work-family conflict and family-work conflict scales. J. Appl. Psychol. 1996, 81, 400–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleff, T. Deskriptive Statistik Und Explorative Datenanalyse: Eine Computergestuützte Einfuührung Mit Excel, SPSS Und STATA; Springer Gabler: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Guttman, L. Some Necessary Conditions for Common-Factor Analysis. Psychometrika 1954, 19, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, H.F. The Application of Electronic Computers to Factor Analysis. Educ Psychol Meas. 1960, 20, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakol, M.; Dennick, R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2011, 2, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Eur. Bus. Review 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Modeling 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H.W.; Hau, K.T.; Wen, Z. In search of golden rules: Comment on hypothesis-testing approaches to setting cutoff values for fit indexes and dangers in overgeneralizing Hu and Bentler’s (1999) findings. Struct. Equ. Model. 2004, 11, 320–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Estabrook, R. Identification of Confirmatory Factor Analysis Models of Different Levels of Invariance for Ordered Categorical Outcomes. Psychometrika 2016, 81, 1014–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.F. Sensitivity of Goodness of Fit Indexes to Lack of Measurement Invariance. Struct. Equ. Model. 2007, 14, 464–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | α If Item Deleted | ITC | Factor Loading | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. I experience my feelings as contradictory | 0.85 | 0.58 | 0.68 | 2.13 | 0.82 |

| 2. I find it difficult to tolerate contradictory emotions or thoughts | 0.85 | 0.59 | 0.69 | 2.09 | 0.85 |

| 3. I am glad when decisions are made for me | 0.85 | 0.52 | 0.62 | 2.24 | 0.83 |

| 4. I often doubt whether an effort is worth it | 0.85 | 0.53 | 0.63 | 2.16 | 0.85 |

| 5. When choosing between attractive options, I find it difficult to decide | 0.85 | 0.57 | 0.68 | 2.32 | 0.83 |

| 6. I find it difficult to tolerate uncertainty | 0.85 | 0.57 | 0.67 | 2.56 | 0.86 |

| 7. I often do not know what I want | 0.84 | 0.66 | 0.76 | 2.04 | 0.86 |

| 8. When I have to choose between two unpleasant alternatives, I find it difficult to decide | 0.85 | 0.57 | 0.67 | 2.08 | 0.76 |

| 9. I often feel torn between different options or perspectives | 0.83 | 72 | 0.81 | 2.20 | 0.84 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Matthias, J.-K.; Baranowski, A.M.; Culmann, A.C.; Tüttenberg, S.C.; Erim, Y.; Morawa, E.; Beschoner, P.; Jerg-Bretzke, L.; Albus, C.; Mogwitz, S.; et al. Validation of the Ambivalence and Uncertainty Scale. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2026, 23, 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010046

Matthias J-K, Baranowski AM, Culmann AC, Tüttenberg SC, Erim Y, Morawa E, Beschoner P, Jerg-Bretzke L, Albus C, Mogwitz S, et al. Validation of the Ambivalence and Uncertainty Scale. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2026; 23(1):46. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010046

Chicago/Turabian StyleMatthias, Julia-Katharina, Andreas M. Baranowski, Anna C. Culmann, Simone C. Tüttenberg, Yesim Erim, Eva Morawa, Petra Beschoner, Lucia Jerg-Bretzke, Christian Albus, Sabine Mogwitz, and et al. 2026. "Validation of the Ambivalence and Uncertainty Scale" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 23, no. 1: 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010046

APA StyleMatthias, J.-K., Baranowski, A. M., Culmann, A. C., Tüttenberg, S. C., Erim, Y., Morawa, E., Beschoner, P., Jerg-Bretzke, L., Albus, C., Mogwitz, S., & Geiser, F. (2026). Validation of the Ambivalence and Uncertainty Scale. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 23(1), 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010046