The Toxicity of Mancozeb Used in Viticulture in Southern Brazil: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Biochemical and Hematological Analyses

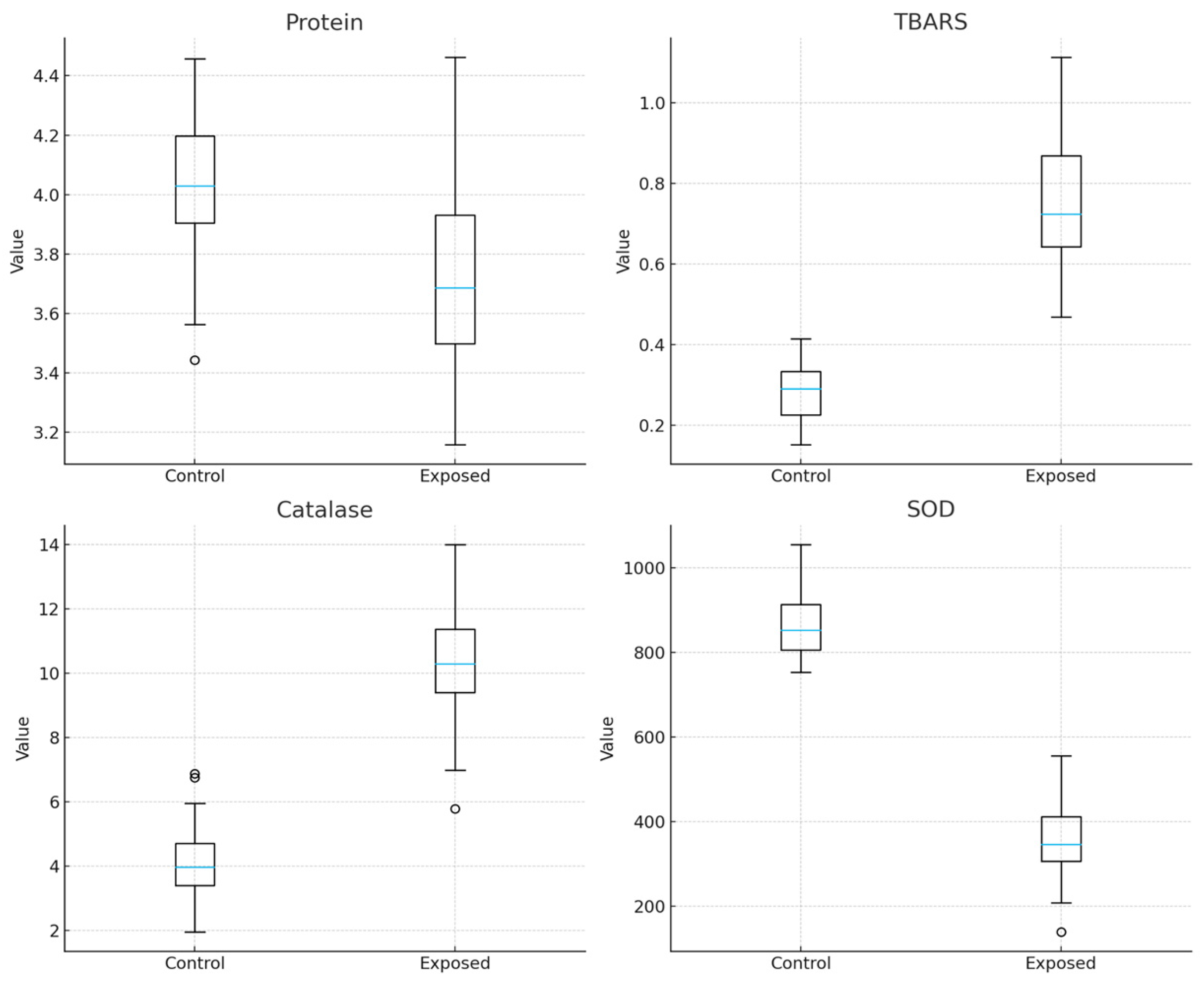

2.3. Oxidative Stress

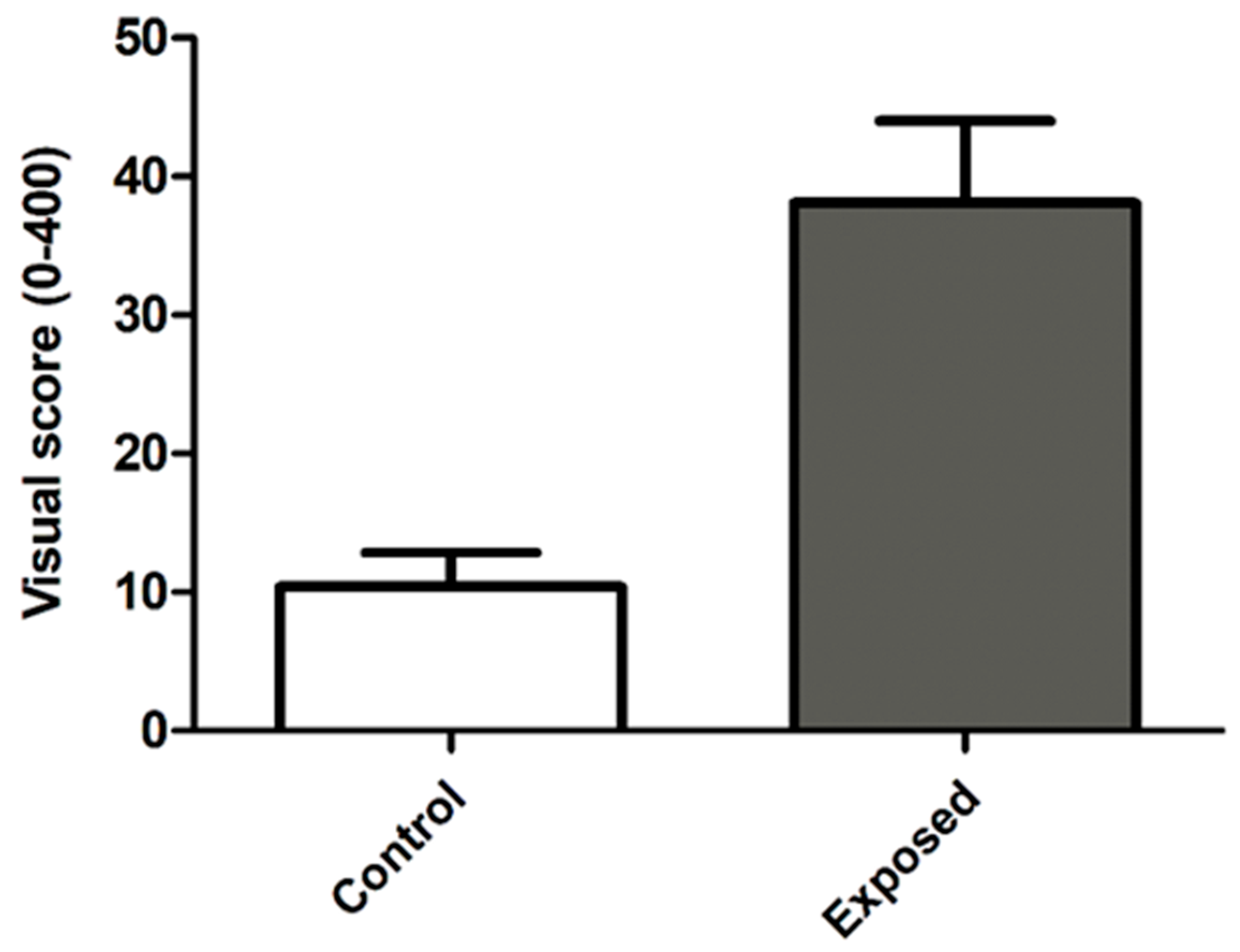

2.4. Genotoxicity Comet Assay

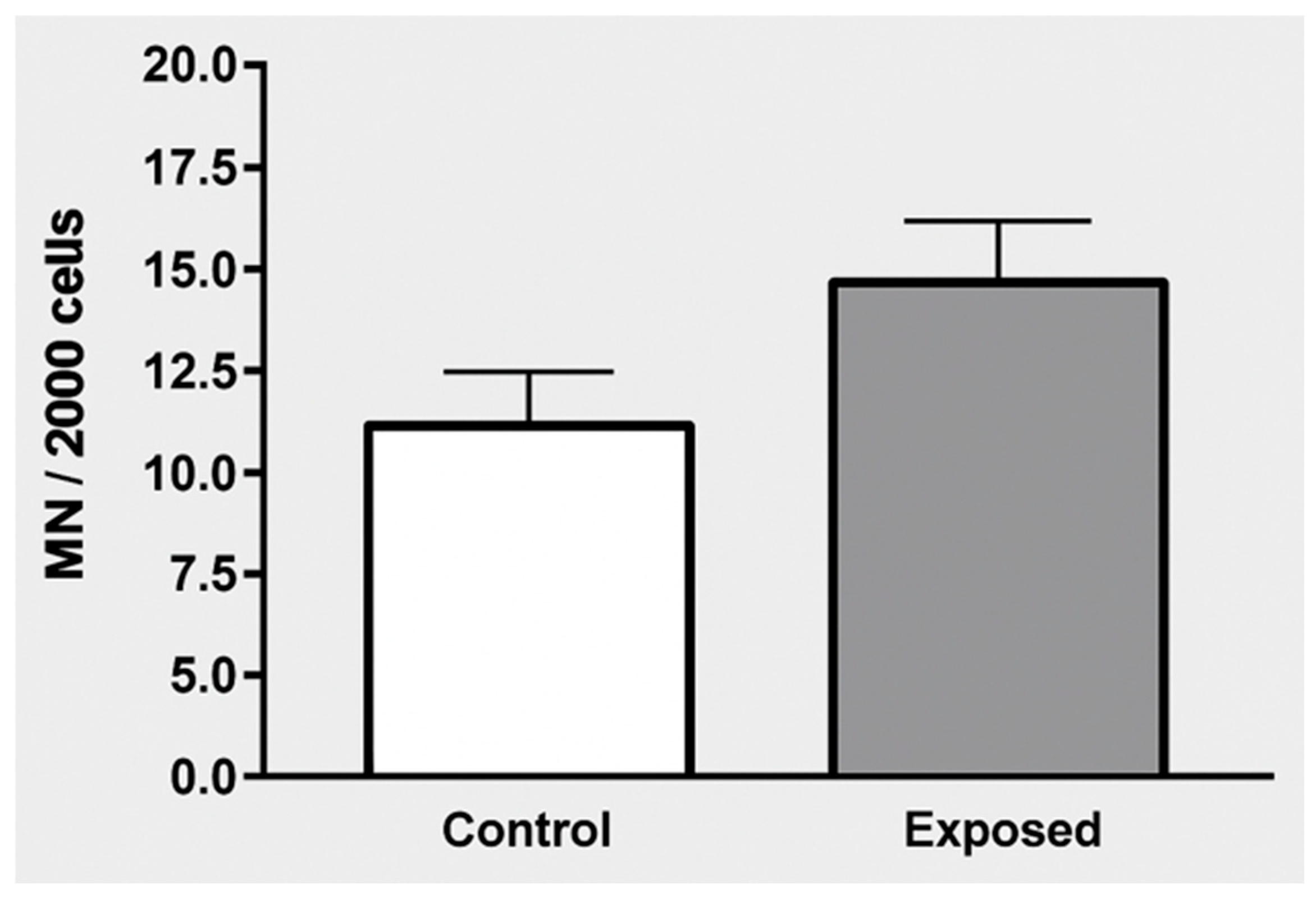

2.5. Micronucleus Test in Exfoliated Buccal Mucosa Cells

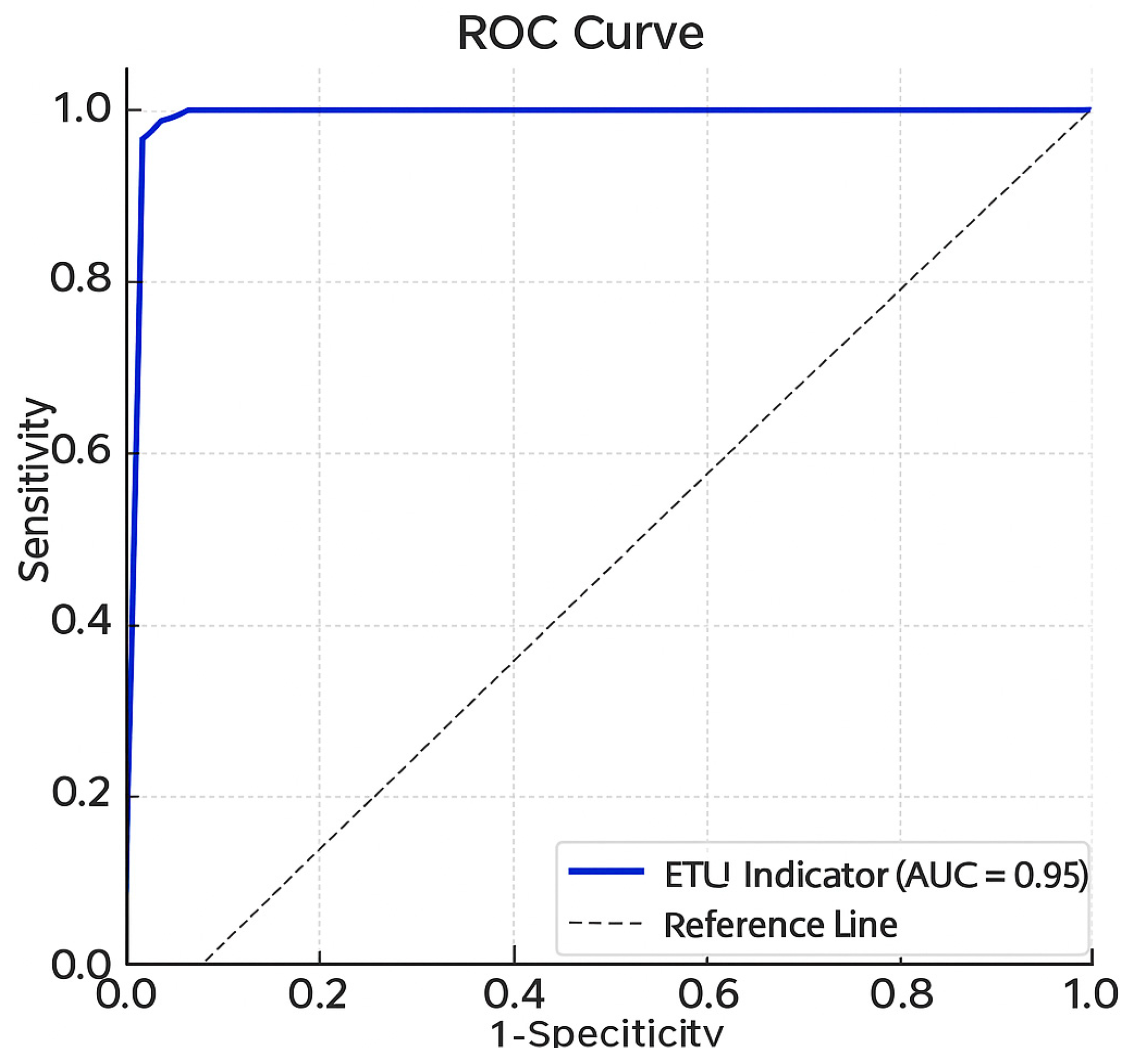

2.6. Urine Analysis and ETU Detection

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALT | Alanine aminotransferase |

| AST | Aspartate aminotransferase |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| AUDIT | Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test |

| BChE | Butyrylcholinesterase |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| BUD + BE | Nuclear buds + broken eggs (DNA damage markers) |

| CAT | Catalase |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| CS2 | Carbon disulfide |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| EBDC | Ethylenebisdithiocarbamate |

| EDTA | Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid |

| EPA | Environmental Protection Agency (USA) |

| ETU | Ethylene thiourea |

| GPx | Glutathione peroxidase |

| LDL | Low-Density Lipoprotein |

| MN | Micronucleus |

| MRM | Multiple Reaction Monitoring |

| NaCl | Sodium chloride |

| NCD | Noncommunicable Chronic Disease |

| PPE | Personal Protective Equipment |

| QuEChERS | Quick, Easy, Cheap, Effective, Rugged, and Safe (pesticide residue extraction method) |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| TBARS | Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Substances |

| UHPLC-MS/MS | Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry |

| Zn | Zinc |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Comet Assay

Appendix A.2. Micronucleus Test in Exfoliated Buccal Mucosa Cells

Appendix A.3. Urine Analysis and ETU Detection

References

- Embrapa. Brazilian Viticulture: Production Data and Trends. 2021. Available online: https://www.infoteca.cnptia.embrapa.br/infoteca/bitstream/doc/1149674/1/Com-Tec-226.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- IBAMA. Consolidation of Data Provided by Registrant Companies of Technical Products, Pesticides, and Related Substances, in Accordance with Article 41 of Decree No. 4,074/2022. Available online: https://dadosabertos.ibama.gov.br/ro/dataset/relatorios-de-comercializacao-de-agrotoxicos (accessed on 13 September 2024).

- Meirelles, L.A.; Veiga, M.M.; Duarte, F. Pesticide contamination and PPE use: Legal and design aspects. Laboreal 2016, 12, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fustinoni, S.; Campo, L.; Liesivuori, J.; Pennanen, S.; Vergieva, T.; van Amelsvoort, L.; Bosetti, C.; Van Loveren, H.; Colosio, C. Biological monitoring and questionnaire for assessing exposure to ethylenebisdithiocarbamates in a multicenter European field study. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2008, 27, 681–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargas, T.S.; Salustriano, N.A.; Klein, B.; Romão, W.; Silva, S.R.C.; Wagner, R.; Scherer, R. Fungicides in red wines produced in South America. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2018, 35, 2135–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, P.K. Toxicity of fungicides. In Veterinary Toxicology, 2nd ed; Gupta, R.C., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 569–580. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez-Santana, M.; Farías-Gómez, C.; Zúñiga-Venegas, L.; Sandoval, R.; Roeleveld, N.; Van Der Velden, K.; Scheepers, P.T.J.; Pancetti, F. Biomonitoring of blood cholinesterases and acylpeptide hydrolase activities in rural inhabitants exposed to pesticides. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0196084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurttio, P.; Savolainen, K. Ethylenethiourea in air and in urine as an indicator of exposure to ethylenebisdithiocarbamate fungicides. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 1990, 16, 203–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurttio, P.; Vartiainen, T.; Savolainen, K. Environmental and biological monitoring of exposure to ethylenebisdithiocarbamate fungicides and ethylenethiourea. Occup. Environ. Med. 1990, 47, 203–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sule, R.O.; Condon, L.; Gomes, A.V. A common feature of pesticides: Oxidative stress. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 5563759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashem, M.A.; Mohamed, W.A.M.; Attia, E.S.M. Assessment of protective potential of Nigella sativa oil against carbendazim- and/or mancozeb-induced hematotoxicity, hepatotoxicity, and genotoxicity. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 1270–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yahia, E.; Aiche, M.A.; Chouabbia, A.; Boulakoud, M.S. Subchronic mancozeb treatement induced liver toxicity via oxidative stress in male wistar rats. Commun. Agric. Appl. Biol. Sci. 2014, 79, 553–559. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kistinger, B.R.; Hardej, D. The ethylene bisdithiocarbamate fungicides mancozeb and nabam alter essential metal levels in liver and kidney and glutathione enzyme activity in liver of Sprague-Dawley rats. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2022, 92, 103849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gök, E.; Deveci, E. Histopathological, immunohistochemical and biochemical alterations in liver tissue after fungicide-mancozeb exposures in Wistar albino rats. Acta Cir. Bras. 2022, 37, e370404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Mancozeb–Human Health Risk Assessment; EPA: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Buege, J.A.; Aust, S.D. Microsomal lipid peroxidation. Methods Enzymol. 1978, 52, 302–310. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein–dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, H.P.; Fridovich, I. The role of superoxide anion in the autoxidation of epinephrine and a simple assay for superoxide dismutase. J. Biol. Chem. 1972, 247, 3170–3175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boveris, A.; Chance, B. The mitochondrial generation of hydrogen peroxide. General properties and effect of hyperbaric oxygen. Biochem. J. 1973, 134, 707–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Collins, A.R. The comet assay for DNA damage and repair: Principles, applications, and limitations. Mol. Biotechnol. 2004, 26, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souza, M.R.; Garcia, A.L.H.; Dalberto, D.; Martins, G.; Picinini, J.; de Souza, G.M.S.; Chytry, P.; Dias, J.F.; Bobermin, L.D.; Quincozes-Santos, A.; et al. Environmental exposure to mineral coal and by-products: Influence on human health and genomic instability. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 287, 117346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, P.; Holland, N.; Bolognesi, C.; Kirsch-Volders, M.; Bonassi, S.; Zeiger, E.; Knasmueller, S.; Fenech, M. Buccal micronucleus cytome assay. Nat. Protoc. 2009, 4, 825–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anastassiades, M.; Lehotay, S.J.; Štajnbaher, D.; Schenck, F.J. Fast and easy multiresidue method employing acetonitrile extraction/partitioning and dispersive solid-phase extraction for the determination of pesticide residues in produce. J. AOAC Int. 2003, 86, 412–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pezzini, M.F.; Rampelotto, P.H.; Dall’AGnol, J.; Guerreiro, G.T.S.; Longo, L.; Uribe, N.D.S.; Lange, E.C.; Álvares-Da-Silva, M.R.; Joveleviths, D. Changes in the gut microbiota of rats after exposure to the fungicide mancozeb. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2023, 466, 116480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dall’Agnol, J.C.; Pezzini, M.F.; Uribe, N.S.; Joveleviths, D. Systemic effects of the pesticide mancozeb—A literature review. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2021, 25, 4113–4120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Embrapa. Cultivo da Videira: Recomendações Técnicas. 2020. Available online: https://ainfo.cnptia.embrapa.br/digital/bitstream/item/112196/1/Cultivo-da-videira-32070.pdf (accessed on 13 September 2024).

- Connolly, A.; Jones, K.; Galea, K.S.; Basinas, I.; Kenny, L.; McGowan, P.; Coggins, M. Exposure assessment using human biomonitoring for glyphosate and fluroxypyr users in amenity horticulture. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2017, 220, 1064–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khayat, C.B.; Costa, E.O.; Gonçalves, M.W.; Cunha, D.M.d.C.e.; da Cruz, A.S.; Melo, C.O.d.A.; Bastos, R.P.; da Cruz, A.D.; Silva, D.d.M.e. Assessment of DNA damage in Brazilian workers occupationally exposed to pesticides: A study from Central Brazil. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2013, 20, 7334–7340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saad-Hussein, A.; Beshir, S.; Taha, M.M.; Shahy, E.M.; Shaheen, W.; Abdel-Shafy, E.A.; Thabet, E. Early prediction of liver carcinogenicity due to occupational exposure to pesticides. Mutat. Res. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 2019, 838, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabat, G.C.; Price, W.J.; Tarone, R.E. On recent meta-analyses of exposure to glyphosate and risk of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in humans. Cancer Causes Control. 2021, 32, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cancino, J.; Soto, K.; Tapia, J.; Muñoz-Quezada, M.T.; Lucero, B.; Contreras, C.; Moreno, J. Occupational exposure to pesticides and symptoms of depression in agricultural workers. A systematic review. Environ. Res. 2023, 231 Pt 2, 116190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthusamy, V.R.; Kannan, S.; Sadhaasivam, K.; Gounder, S.S.; Davidson, C.J.; Boeheme, C.; Hoidal, J.R.; Wang, L.; Rajasekaran, N.S. Acute exercise stress activates Nrf2/ARE signaling and promotes antioxidant mechanisms in the myocardium. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2012, 52, 366–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ghignatti, P.V.d.C.; Russo, M.K.B.; Becker, T.; Guecheva, T.N.; Teixeira, L.V.; Lehnen, A.M.; Schaun, M.I.; Leguisamo, N.M. Preventive aerobic training preserves sympathovagal function and improves DNA repair capacity of peripheral blood mononuclear cells in rats with cardiomyopathy. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 6422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Aprioku, J.S.; Amamina, A.M.; Nnabuenyi, P.A. Mancozeb-induced hepatotoxicity: Protective role of curcumin in rat animal model. Toxicol. Res. 2023, 12, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lamat, H.; Sauvant-Rochat, M.-P.; Tauveron, I.; Bagheri, R.; Ugbolue, U.C.; Maqdasi, S.; Navel, V.; Dutheil, F. Metabolic syndrome and pesticides: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 305, 119288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hundekari, I.; Suryakar, A.; Rathi, D. Acute organo-phosphorus pesticide poisoning in North Karnataka, India: Oxidative damage, haemoglobin level and total leukocyte. Afr. Health Sci. 2013, 13, 129–136–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Costa, C.; Teodoro, M.; Giambò, F.; Catania, S.; Vivarelli, S.; Fenga, C. Assessment of Mancozeb Exposure, Absorbed Dose, and Oxidative Damage in Greenhouse Farmers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Baltazar, M.T.; Dinis-Oliveira, R.J.; Bastos, M.d.L.; Tsatsakis, A.M.; Duarte, J.A.; Carvalho, F. Pesticides exposure as etiological factors of Parkinson’s disease and other neurodegenerative diseases—A mechanistic approach. Toxicol. Lett. 2014, 230, 85–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calsolaro, V.; Edison, P. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease: Current evidence and future directions. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2016, 12, 719–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, C.M.; Ross, G.W.; Jewell, S.A.; Hauser, R.A.; Jankovic, J.; Factor, S.A.; Bressman, S.; Deligtisch, A.; Marras, C.; Lyons, K.E.; et al. Occupation and risk of parkinsonism: A multicenter case-control study. Arch. Neurol. 2009, 66, 1106–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayden, K.M.; Norton, M.C.; Darcey, D.; Ostbye, T.; Zandi, P.P.; Breitner, J.C.S.; Welsh-Bohmer, K.A. Cache County Study Investigators. Occupational exposure to pesticides increases the risk of incident AD: The Cache County Study. Neurology 2010, 74, 1524–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kamel, F.; Hoppin, J.A. Association of pesticide exposure with neurologic dysfunction and disease. Environ. Health Perspect. 2004, 112, 950–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, C.; Koifman, S. Pesticide exposure and Parkinson’s disease: Epidemiological evidence of association. NeuroToxicology 2012, 33, 947–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafalou, S.; Abdollahi, M. Pesticides and human chronic diseases: Evidences, mechanisms, and perspectives. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2013, 268, 157–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandić-Rajčević, S.; Rubino, F.M.; Colosio, C. Establishment of health-based biological exposure limits for pesticides: A proof of principle study using mancozeb. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2020, 115, 104689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colosio, C.; Fustinoni, S.; Corsini, E.; Bosetti, C.; Birindelli, S.; Boers, D.; Campo, L.; La Vecchia, C.; Liesivuori, J.; Pennanen, S.; et al. Changes in serum markers indicative of health effects in vineyard workers after exposure to the fungicide mancozeb: An Italian study. Biomarkers 2007, 12, 574–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Non-Exposed Group (n = 44) | Exposed Group (n = 50) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)—mean ± SD | 49.1 ± 12.9 | 44.6 ± 14.6 | 0.124 |

| Sex—No. (%) | 0.008 | ||

| Female | 14 (31.8) | 4 (8.0) | |

| Male | 30 (68.2) | 46 (92.0) | |

| Ethnic group—No. (%) | 0.191 | ||

| White | 40 (90.9) | 50 (100.0) | |

| Black | 1 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Mixed race | 2 (4.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Asian descent | 1 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Educational level—No. (%) | 0.753 | ||

| Primary education | 16 (36.4) | 22 (44.0) | |

| Secondary education | 19 (43.2) | 19 (38.0) | |

| Higher education | 9 (20.5) | 9 (18.0) | |

| Current comorbidities or diseases (yes)—No. (%) | 21 (47.7) | 23 (46.0) | 1.000 |

| Hypertension | 3 (6.8) | 13 (26.0) | 0.028 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1 (2.3) | 3 (6.0) | 0.620 |

| Dyslipidemia | 0 (0.0) | 6 (12.0) | 0.028 |

| Hepatitis | 2 (4.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0.216 |

| Common mental disorder | 4 (9.1) | 3 (6.0) | 0.702 |

| Musculoskeletal/rheumatologic disease | 8 (18.2) | 2 (4.0) | 0.042 |

| Other conditions | 7 (15.9) | 7 (14.0) | 1.000 |

| Use of medications—No. (%) | 12 (27.3) | 25 (50.0) | 0.041 |

| Use of herbal teas, supplements, and/or vitamins—No. (%) | 8 (18.2) | 1 (2.0) | 0.011 |

| Alcohol consumption—No. (%) | 30 (68.2) | 45 (90.0) | 0.018 |

| Smoking—No. (%) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (4.0) | 0.497 |

| Variables | Non-Exposed Group (n = 44) | Exposed Group (n = 50) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| ETU indicator—median (P25–P75) | 0.05 (0.05–1.46) | 168.9 (143.8–220.6) | <0.010 |

| Binucleated—mean ± SD | 28.2 ± 11.5 | 24.9 ± 10.1 | 0.139 |

| Micronuclei—median (P25–P75) | 8 (3.3–14.8) | 9.5 (6–16) | 0.105 |

| BUD + BE—median (P25–P75) | 2 (1–7) | 4 (3–7) | 0.094 |

| Damage—median (P25–P75) | 0 (0–20) | 25 (0–41.5) | <0.001 |

| Variables | b (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| AST * | 7.90 (−0.30 to 16.1) | 0.059 |

| ALT ** | 8.02 (−4.06 to 20.1) | 0.190 |

| Creatinine *** | 0.03 (−0.02 to 0.08) | 0.219 |

| Glucose * | −14.2 (−27.2 to −1.08) | 0.034 |

| Total cholesterol *** | −14.8 (−37.1 to 7.56) | 0.192 |

| LDL *** | −18.1 (−38.2 to 2.03) | 0.077 |

| ETU indicator * | 213.8 (168.5 to 259.1) | <0.001 |

| Oxidative stress protein * | −0.28 (−0.43 to −0.14) | <0.001 |

| TBARS * | 0.52 (0.46 to 0.57) | <0.001 |

| Catalase * | 6.38 (5.63 to 7.13) | <0.001 |

| SOD * | −496.6 (−540.4 to −452.8) | <0.001 |

| DNA damage | 19.6 (8.13 to 31.0) | 0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Toniasso, S.d.C.C.; Baldin, C.P.; Sampaio, V.C.; Costa, R.B.d.; Uribe, N.D.S.; Riedel, P.G.; Costa, D.; Marroni, N.; Schemitt, E.; Brasil, M.; et al. The Toxicity of Mancozeb Used in Viticulture in Southern Brazil: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2026, 23, 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010034

Toniasso SdCC, Baldin CP, Sampaio VC, Costa RBd, Uribe NDS, Riedel PG, Costa D, Marroni N, Schemitt E, Brasil M, et al. The Toxicity of Mancozeb Used in Viticulture in Southern Brazil: A Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2026; 23(1):34. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010034

Chicago/Turabian StyleToniasso, Sheila de Castro Cardoso, Camila Pereira Baldin, Vittoria Calvi Sampaio, Raquel Boff da Costa, Nelson David Suarez Uribe, Patrícia Gabriela Riedel, Débora Costa, Norma Marroni, Elizângela Schemitt, Marilda Brasil, and et al. 2026. "The Toxicity of Mancozeb Used in Viticulture in Southern Brazil: A Cross-Sectional Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 23, no. 1: 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010034

APA StyleToniasso, S. d. C. C., Baldin, C. P., Sampaio, V. C., Costa, R. B. d., Uribe, N. D. S., Riedel, P. G., Costa, D., Marroni, N., Schemitt, E., Brasil, M., Garcia, A. L. H., da Silva, J., Dallegrave, E., Brum, M. C. B., Pereira, R. M., dos Reis, F. L., Pereira, L. d. S., Klein, E. N. M., Kassim, H., & Joveleviths, D. (2026). The Toxicity of Mancozeb Used in Viticulture in Southern Brazil: A Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 23(1), 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010034