Loneliness by Design: The Structural Logic of Isolation in Engagement-Driven Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

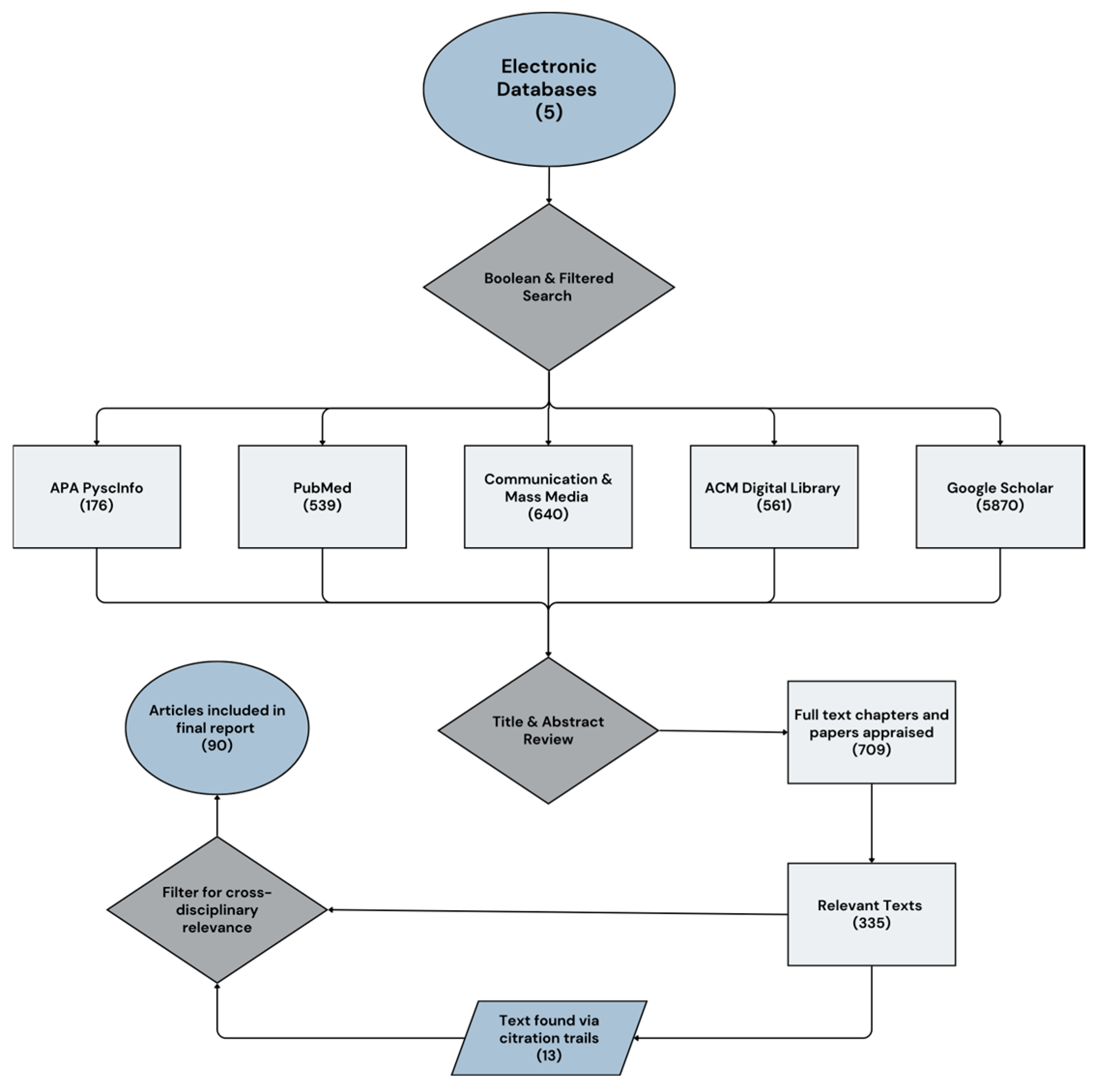

2. Methodology

2.1. Research Questions

- How is loneliness framed in the fields of digital and technological design (including HCI and communication studies), compared to its clinical and public health representations?

- How can these perspectives inform the design of ethical digital public health interventions?

2.2. Rationale for Review Type

2.3. Search Strategy

2.4. Inclusion/Exclusion, Screening and Selection Processes

3. Analysis and Results

4. The Hegemony of Digital Design Paradigms

4.1. Hegemonic Digital Infrastructures and the Structuring of Loneliness

4.2. Simulated Intimacy and the Erosion of Relational Depth

4.3. Design Affordances, Sensory Deficits, and Affective Disconnection

4.4. Individualisation, Medicalization, and the Obfuscation of Structural Causes

5. Algorithmic Infrastructures as Mediator and Producer

5.1. Technology as Mediator

5.2. Technology as Producer

6. Structural Logics of Platform Capitalism and Algorithmic Control

6.1. Platform Capitalism and the Infrastructure of Loneliness

6.2. Affective AI and the Commodification of Emotional Vulnerability

6.3. Algorithmic Affordances and the Redefinition of Connection

6.4. Extraction, Bias, and the Medicalized Reframing of Loneliness

7. Public Health and Technological Design

7.1. The Systemic Framing of Loneliness in Public Health and Design

7.2. Digital Interventions and Conditional Promises of Connection

7.3. Designing for Relational Justice: Toward Ethical and Inclusive Systems

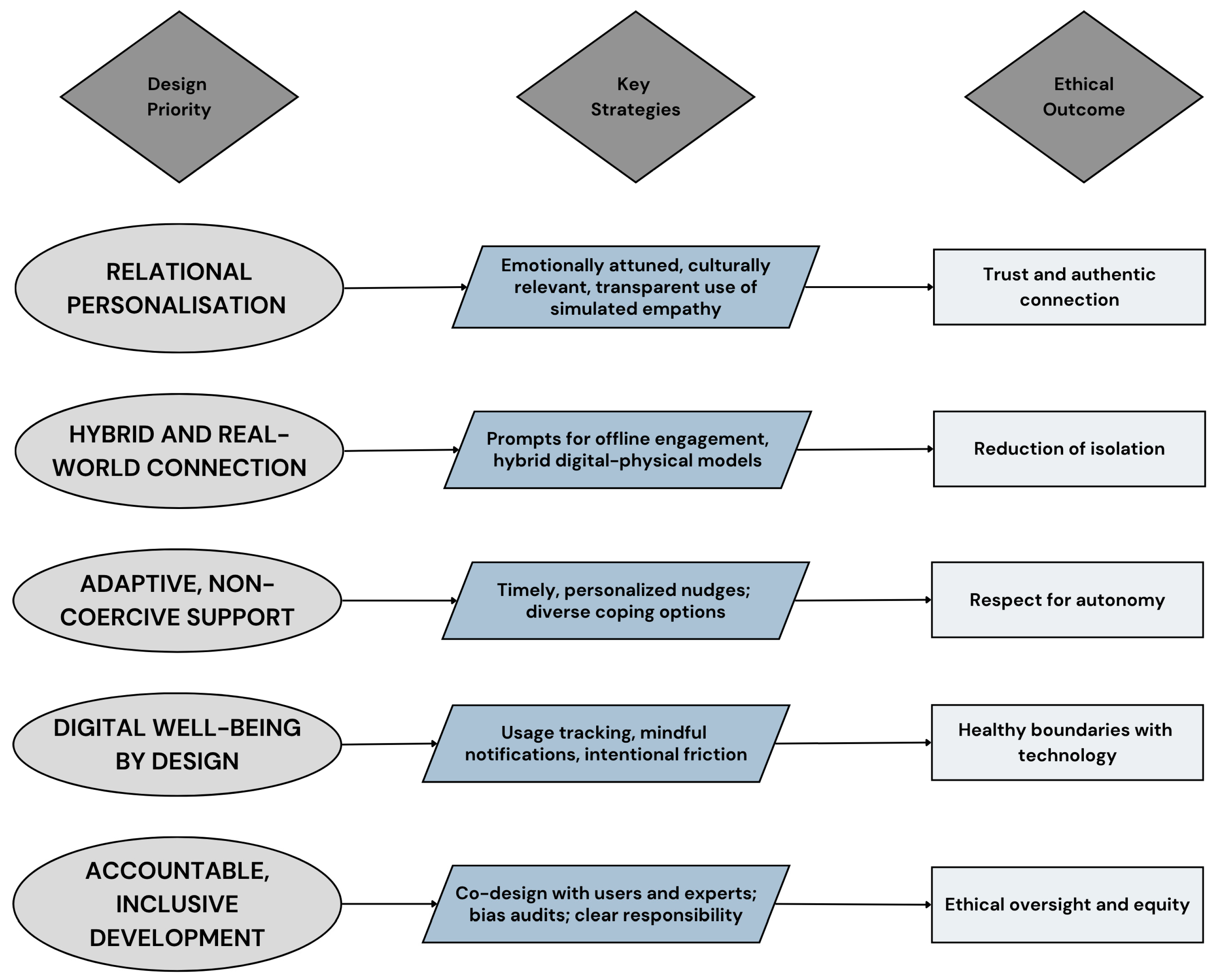

8. Digital Public Health Design Framework

9. Conclusions

10. Limitations and Future Directions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Petersen, A. Pandemics as Socio-Political Phenomena. In Pandemic Societies a Critical Public Health Perspective; Bristol University Press: Bristol, UK, 2024; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, N.; Khanna, D.; El Asmar, M.L.; Qualter, P.; El-Osta, A. Addressing loneliness and social isolation in 52 countries: A scoping review of National policies. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jentoft, E.E. Technology and older adults in British loneliness policy and political discourse. Front. Digit. Health 2023, 5, 1168413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jentoft, E.E.; Sandset, T.; Haldar, M. Problematizing loneliness as a public health issue: An analysis of policy in the United Kingdom. Crit. Policy Stud. 2025, 19, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isolation, Loneliness, and COVID-19: Pandemic Leads to Sharp Increase in Mental Health Challenges, Social Woes. Available online: http://angusreid.org/isolation-and-loneliness-covid19/ (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Weissbourd, R.; Batanova, M.; Lovison, V.; Torres, E. Loneliness in America: How the Pandemic Has Deepened an Epidemic of Loneliness and What We Can Do About It. Report by the Making Caring Common Project in Harvard Graduate School of Education 2021. Available online: https://mcc.gse.harvard.edu/reports/loneliness-in-america (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Hawkley, L. Public policy and the reduction and prevention of loneliness and social isolation. In Loneliness and Social Isolation in Old Age, Correlates and Implications; Routeledge: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 181–190. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5-TR (5th Edition Text Revision); American Psychiatric Association Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- von Känel, R.; Weilenmann, S.; Spiller, T.R. Loneliness Is Associated with Depressive Affect, But Not with Most Other Symptoms of Depression in Community-Dwelling Individuals: A Network Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caciopo, S.; Grippo, A.J.; London, S.; Cacioppo, J.T. Loneliness: Clinical Import and Interventions. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. A J. Assoc. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 10, 238–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hang, S.; Jost, G.M.; Guyer, A.E.; Robins, R.W.; Hastings, P.D.; Hostinar, C.E. Understanding the development of chronic loneliness in youth. Child Dev. Perspect. 2024, 18, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokach, A.; Boulazreg, S. Loneliness or Solitude: Which will we experience? Ruch Filoz. 2023, 79, 95–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, L. Canadian perspectives on loneliness; digital communication as meaningful connection. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1389099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, M.H.; Rodebaugh, T.L.; Eres, R.; Long, K.M.; Penn, D.L.; Gleeson, J.F.M. A Pilot Digital Intervention Targeting Loneliness in Youth Mental Health. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieves, J.C.; Osorio, M.; Rojas-Velazquez, D.; Magallanes, Y.; Brännström, A. Digital Companions for Well-being: Challenges and Opportunities. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2024, 219336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.G.S.; Nogueras, D.; van Woerden, H.C.; Kiparoglou, V. Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Digital Technology Interventions to Reduce Loneliness in Older Adults: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e24712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freitas, J.D.; Uguralp, A.K.; Uguralp, Z.O.; Stefano, P. AI Companions Reduce Loneliness. arXiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löchner, J.; Carlbring, P.; Schuller, B.; Torous, J.; Sander, L.B. Digital interventions in mental health: An overview and future perspectives. Internet Interv. 2025, 40, 100824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, F.; Al Khalifah, G.; Oyebode, O.; Orji, R. Apps for Mental Health: An Evaluation of Behavior Change Strategies and Recommendations for Future Development. Front. Artif. Intell. 2019, 2, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matias, J. Nudging Algorithms by Influencing Human Behavior: Effects of Encouraging Fact-Checking on News Rankings. Open Science Framework. 2020. Available online: https://osf.io/m98b6/ (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Toner, J.; Allen-Collinson, J.; Jones, L. ‘I guess I was surprised by an app telling an adult they had to go to bed before half ten’: A phenomenological exploration of behavioural ‘nudges’. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. 2024, 14, 413–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torous, J.; Bucci, S.; Bell, I.H.; Kessing, L.V.; Faurholt-Jepsen, M.; Whelan, P.; Carvalho, A.F.; Keshavan, M.; Linardon, J.; Firth, J. The growing field of digital psychiatry: Current evidence and the future of apps, social media, chatbots, and virtual reality. World Psychiatry 2021, 20, 318–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mele, C.; Russo Spena, T.; Kaartemo, V.; Marzullo, M.L. Smart nudging: How cognitive technologies enable choice architectures for value co-creation. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 129, 949–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruckenstein, M. The Feel of Algorithms; University of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Salamida, M. Designing Meaningful Future Digital Interactions: Fostering Wellbeing to Reduce Techno-Induced Stress. 2024. Available online: https://www.politesi.polimi.it/handle/10589/227729 (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Nowotny, H. In AI We Trust: Power, Illusion and Control of Predictive Algorithms; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Shoemaker, P.J.; Vos, T. Gatekeeping Theory; Taylor & Francis: Oxfordshire, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie, T. The Politics of ‘Platforms. New Media Soc. 2010, 12, 347–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, T. Do Not Recommend? Reduction as a Form of Content Moderation. Soc. Media Soc. 2022, 8, 20563051221117552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couldry, N. Media in Modernity: A Nice Derangement of Institutions. Rev. Int. Philos. 2017, 281, 259–279. Available online: https://shs.cairn.info/journal-revue-internationale-de-philosophie-2017-3-page-259?lang=en (accessed on 26 May 2025). [CrossRef]

- Zuboff, S. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power; Public Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Casas-Cortés, M.; Cañedo, M.; Diz, C. Platform Capitalism; Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Anthropology: Oxford, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufecki, Z. “Not This One”: Social Movements, the Attention Economy, and Microcelebrity Networked Activism. Am. Behav. Sci. 2013, 57, 848–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srnicek, N. The Challenges of Platform Capitalism: Understanding the Logic of a New Business Model. Juncture 2017, 23, 254–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkle, S. Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other; Basic Books Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Illouz, E. Cold Intimacies: The Making of Emotional Capitalism; Polity: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Pariser, E. The Filter Bubble: What The Internet Is Hiding from You; Penguin Books Limited: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Wong, G.; Jagosh, J.; Greenhalgh, J.; Manzano, A.; Westhorp, G.; Pawson, R. Protocol—The RAMESES II Study: Developing Guidance and Reporting Standards for Realist Evaluation. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e008567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, G.; Greenhalgh, T.; Westhorp, G.; Buckingham, J.; Pawson, R. RAMESES Publication Standards: Meta-Narrative Reviews. BMC Med. 2013, 11, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukhera, J. Narrative Reviews: Flexible, Rigorous, and Practical. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2022, 14, 414–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ågerfalk, P.J. Artificial Intelligence as Digital Agency. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2020, 29, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, A. Live Like Nobody Is Watching: Relational Autonomy in the Age of Artificial Intelligence Health Monitoring; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kuss, P.; Meske, C. From Entity to Relation? Agency in the Era of Artificial Intelligence; Social Science Research Network: Rochester, NY, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dattathrani, S.; De’, R. The Concept of Agency in the Era of Artificial Intelligence: Dimensions and Degrees. Inf. Syst. Front. 2023, 25, 29–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkitt, I. Relational Agency: Relational Sociology, Agency and Interaction. Eur. J. Soc. Theory 2016, 19, 322–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, G.; Moore, L.; Hennessy, M.; Sandset, T.; Jentoft, E.E.; Haldar, M. What kind of a problem is loneliness? Representations of connectedness and participation from a study of telepresence technologies in the UK. Front. Digit. Health 2024, 6, 1304085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Fu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Radesky, J.; Hiniker, A. The Engagement-Prolonging Designs Teens Encounter on Very Large Online Platforms. arXiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, L. Isolated Circuits: Human Experience and Robot Design for the Future of Loneliness. Ph.D. Thesis, Toronto Metropolitan University, Toronto, ON, Canada, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Cahyono, M.Y.M.; Adiawaty, S. The Ambivalent Impact of Digital Technology on Loneliness: Navigating Connection and Isolation in the Digital Age. Sinergi Int. J. Psychol. 2024, 2, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, K.A. Digital loneliness—Changes of social recognition through AI companions. Front. Digit. Health 2024, 6, 1281037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comment, T.D. The Impact of Social Media Use on Loneliness Through an Interpersonal-Connection-Behavior Framework. Master’s Thesis, Kent State University, Kent, OH, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- George, A.S.; George, A.S.H.; Baskar, T.; Pandey, D. The Allure of Artificial Intimacy: Examining the Appeal and Ethics of Using Generative AI for Simulated Relationships. Partn. Univers. Int. Innov. J. 2023, 1, 132–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemper, J. Frictionlesssness: The Silicon Valley Philosophy of Seamless Technology and the Aesthetic Value of Imperfection; Bloomsbury Publishing: Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan, P. Beyond Biology: AI as Family and the Future of Human Bonds and Relationships. HAL Archives Ouvertes. Available online: https://hal.science/hal-04987496 (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Fullam, E. The Social Life of Mental Health Chatbots. Ph.D. Thesis, Birbeck, University of London, London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Schmidt, R. Exploring a Behavioral Model of “Positive Friction” in Human-AI Interaction. In Design, User Experience, and Usability; Marcus, A., Rosenzweig, E., Soares, M.M., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadows, R.; Hine, C. Entanglements of Technologies, Agency and Selfhood: Exploring the Complexity in Attitudes Toward Mental Health Chatbots. Cult. Med. Pyschiatry 2024, 48, 840–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milli, S.; Carroll, M.; Wang, Y.; Pandey, S.; Zhao, S.; Dragan, A.D. Engagement, User Satisfaction and the Amplification of Divisive Content on Social Media. PNAS Nexus 2025, 4, pgaf062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, L.; Rocher, L.; Valdivia, A. Characterizing and Modeling Harms from Interactions with Design Patterns in AI interfaces. arXiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auf, H.; Dagman, J.; Renström, S.; Chaplin, J. Gamification and Nudging Techniques for Improving User Engagement in Mental Health and Well-being Apps. Proc. Des. Soc. 2021, 1, 1647–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jecker, N.S.; Sparrow, R.; Lederman, Z.; Ho, A. Digital Humans to Combat Loneliness and Social Isolation: Ethics Concerns and Policy Recommendations. Hastings Cent. Rep. 2024, 54, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagan, O. Organized loneliness and its discontents. Divers. Incl. Res. 2024, 1, e12008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magid, K.; Sagui-Henson, S.J.; Sweet, C.C.; Smith, B.J.; Chamberlain, C.E.W.; Levens, S.M. The Impact of Digital Mental Health Services on Loneliness and Mental Health: Results from a Prospective, Observational Study. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2024, 31, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primack, B.A.; Shensa, A.; Sidani, J.E.; Whaite, E.O.; Lin, L.Y.; Rosen, D.; Colditz, J.B.; Radovic, A.M.; Miller, E. Social Media Use and Perceived Social Isolation Among Young Adults in the U.S. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2017, 53, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fahy, M.; Barry, M. Investigating the interplay of loneliness, computer-mediated communication, online social capital, and well-being: Insights from a COVID-19 lockdown study. Front. Digit. Health 2024, 6, 1289451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woolley, S. Computational Propaganda: Political Parties, Politicians, and Political Manipulation on Social Media; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kitchen, N.; Curtis, S. “If you Build It, They Will Come.” Infrastructure, Hegemonic Transition, and Peaceful Change. Glob. Stud. Q. 2025, 5, ksaf021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghantous, D. Between the Self and Signal the Dead Internet & A Crisis of Perception. Master’s Thesis, OCAD University, Toronto, ON, Canada, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Tufekci, Z. Algorithmic Harms Beyond Facebook and Google; Emergent Challenges of Computational Agency. Colo. Technol. Law J. 2015, 13, 203. [Google Scholar]

- Grabher, G. Enclosure 4.0: Seizing Data, Selling Predictions, Scaling Platforms. Sociologica 2020, 14, 241–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couldry, N.; Mejias, U.A. Data Colonialism: Rethinkking Big Data’s Relation to the Contemporary Subject. Telev. New Media 2019, 20, 336–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozdag, E.; van den Hoven, J. Breaking the Filter Bubble: Democracy and Design. Ethics Inf. Technol. 2015, 17, 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaheer, S. Designing for Digital Well-Being: Applying Behavioral Science to Reduce Tech Addiction. Int. J. Res. Lead. Publ. 2023, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenzwig, M. Boyfriends for Rent, Robots, Camming: How the Business of Loneliness Is Booming. In The Guardian. 1 November 2020. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2020/nov/01/loneliness-business-booming-pandemic (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Li, H.; Zhang, R.; Lee, Y.C.; Kraut, R.E.; Mohr, D.C. Systematic review and meta-analysis of AI-based conversational agents for promoting mental health and well-being. npj Digit. Med. 2023, 6, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maples, B.; Cerit, M.; Vishwanath, A.; Pea, R. Loneliness and suicide mitigation for students using GPT3-enabled chatbots. npj Ment. Health Res. 2024, 3, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duradoni, M.; Serritella, E.; Severino, F.P.; Guazzini, A. Exploring the Relationships Between Digital Life Balance and Internet Social Capital, Loneliness, Fear of Missing Out, and Anxiety. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2024, 2024, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokić, B.; Ristić Dedić, Z.; Šimon, J. Time Spent Using Digital Technology, Loneliness, and Well-Being Among Three Cohorts of Adolescent Girls and Boys—A Moderated Mediation Analysis. Psihol. Teme 2024, 33, 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendse, S.R.; Nkemelu, D.; Bidwell, N.J.; Jadhav, S.; Pathare, S.; De Choudhury, M.; Kumar, N. From Treatment to Healing: Envisioning a Decolonial Digital Mental Health. In Proceedings of the 2022 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, New Orleans, LA, USA, 29 April–5 May 2022; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infurna, F.J.; Dey, N.E.Y.; Gonzalez Avilès, T.; Grimm, K.J.; Lachman, M.E.; Gerstorf, D. Loneliness in Midlife: Historical Increases and Elevated Levels in the United States Compared with Europe. Am. Psychol. 2024, 80, 744–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO Launches Commission to Foster Social Connection. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/15-11-2023-who-launches-commission-to-foster-social-connection (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Yang, Y.; Wang, C.; Xiang, X.; An, R. AI Applications to Reduce Loneliness Among Older Adults: A Systematic Review of Effectiveness and Technologies. Healthcare 2025, 13, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersson, G.; Titov, N. Advantages and Limitations of Internet-Based Interventions for Common Mental Disorders. World Psychiatry 2014, 13, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naslund, J.A.; Aschbrenner, K.A.; Araya, R.; Marsch, L.A.; Unützer, J.; Patel, V.; Bartels, S.J. Digital Technology for Treating and Preventing Mental Disorders in Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries: A Narrative Review of the Literature. Lancet Psychiatry 2017, 4, 486–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danieli, M.; Ciulli, T.; Mousavi, S.M.; Riccardi, G. A Conversational Artificial Intelligence Agent for a Mental Health Care App: Evaluation Study of Its Participatory Design. JMIR Form. Res. 2021, 5, e30053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thieme, A.; Hanratty, M.; Lyone, M.; Palacios, J.; Marques, R.F.; Morrison, C.; Doherty, G. Designing Human-centered AI for Mental Health: Developing Clinically Relevant Applications for Online CBT Treatment. ACM Trans. Comput.-Hum. Interact. 2023, 30, 1–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joachim, S.; Forkan, A.R.M.; Jayaraman, P.P.; Morshed, A.; Wickramsinghe, N. A Nudge-Inspired AI-Driven Health Platform for Self-Management of Diabetes. Sensors 2022, 22, 4620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiam, J.; Lim, A.; Teredesai, A. NudgeRank: Digital Algorithmic Nudging for Personalized Health. In Proceedings of the KKD ’24: The 30th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Barcelona, Spain, 25–29 August 2024; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 4873–4884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretolesi, D.; Motnikar, L.; Bieg, T.; Gafert, M.; Uhl, J. Exploring User Preferences: Customisation and Attitudes towards Notification in Mobile Health and Well-Being Applications. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2025, 44, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankovič, A.; Kolenik, T.; Pejović, V. Can Personalization Persuade? Study of Notification Adaptation in Mobile Behavior Change Intervention Application. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maalsen, S. Algorithmic Epistemologies and Methodologies: Algorithmic Harm, Algorithmic Care and Situated Algorithmic Knowledges. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2023, 47, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loosen, W.; Scholl, A. The Epistemological Dimension of Algorithms. Constr. Found. 2021, 16, 369–371. [Google Scholar]

- Milano, S.; Prunkl, C. Algorithmic Profiling as a Source of Hermeneutical Injustice. Philos. Stud. 2025, 182, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynch, C.R.; Bissell, D.; House-Peters, L.A.; Del Casino, V.J., Jr. Robotics, Affective Displacement, and the Automation of Care. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2022, 112, 684–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Lin, I.W.; Miner, A.S.; Atkins, D.C.; Althoff, T. Human-AI Collaboration Enables More Empathetic Conversations in Text-Based Peer-to Peer Mental Health Support. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2023, 5, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pralat, N.; Ischen, C.; Voorveld, H. Feeling Understood by AI: How Empathy Shapes Trust and Influences Patronage Intentions in Conversational AI. In Chatbots and Human-Centered AI; Følstad, A., Papadopoulos, S., Araujo, T., Law, E.L.-C., Luger, E., Hobert, S., Brandtzaeg, P.B., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 234–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Research Tradition | Framing of Loneliness + Technology | Methodological Orientation | Design Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Public Health | Technology positioned as a scalable mechanism to address loneliness, primarily treated as a modifiable health risk. | Epidemiological surveys, longitudinal studies, validated psychometric scales, intervention trials. | Integrate structural critiques into intervention design to avoid treating loneliness solely as an individual pathology. |

| Behavioural Science & Psychology | Technology as a medium for behaviour change, social skills training, and cognitive reframing to reduce loneliness. | Behaviour change theory, CBT, nudge theory, experimental and quasi-experimental studies. | Ensure long-term relational outcomes by combining behavioural strategies with safeguards against dependency and over-reliance |

| HCI/Design | Technology as a sociotechnical system whose affordances shape relational depth, agency, and connection quality. | User-centered and participatory design, affordance theory, systems thinking, usability studies. | Prioritizes hybrid online-offline connections, design “positive friction” and preserve user agency in relational contexts. |

| Communication & Media | Technology as embedded in political-economic systems that commodify connection and influence emotional life. | Political economy of media, gatekeeping theory, critical discourse analysis. | Address platform logics and governance structures to design interventions that resist commodification and structural disconnection. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dwyer, L. Loneliness by Design: The Structural Logic of Isolation in Engagement-Driven Systems. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1394. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091394

Dwyer L. Loneliness by Design: The Structural Logic of Isolation in Engagement-Driven Systems. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(9):1394. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091394

Chicago/Turabian StyleDwyer, Lauren. 2025. "Loneliness by Design: The Structural Logic of Isolation in Engagement-Driven Systems" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 9: 1394. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091394

APA StyleDwyer, L. (2025). Loneliness by Design: The Structural Logic of Isolation in Engagement-Driven Systems. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(9), 1394. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091394