Quantification of Urticating Setae of Oak Processionary Moth (Thaumetopoea processionea) and Exposure Hazards

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setae Quantification

2.2. Airborne Setae Dispersion

2.2.1. Close Range, Circular Dispersion

2.2.2. Horizontal Setae Dispersion

3. Results

3.1. Setae Quantification

- OPM pupation tents can reach volumes of ca. 0.2–12.0 L each, depending on OPM population density (see Supplementary Data 2.3.3).

- An OPM pupation tent with a volume of 1 L contains from 400 individuals according to Mühlfeit et al. [52] to 998 ± 246 individuals (mean ± SD) according to the counting in the present study. The first values refer to loose, less densely woven tents, whereas the latter values pertain to compact, densely woven tents.

- An OPM colony of 400–1000 individuals produces 343–857 million setae within one season (Table 4).

- A single oak tree of 13 ± 4 m height and 40 ± 15 cm DBH (mean ± SD) can be infested by OPM with 28 ± 4 L(mean ± SE) of pupation tents during an outbreak culmination, for example. Regarding the mean tent volume, the potential contamination from such a tree with setae from larvae of the instars L3-L6 within one season would extend over the following ranges for loose vs. compact tents (Table 4):

- ∘

- Mean (28 L): 9.6–24.0 billion (109) setae;

- ∘

- Lower limit of the 95% confidence interval (21 L): 7.2–18.0 billion setae;

- ∘

- Upper limit of the 95% confidence interval (36 L): 12.9–30.9 billion setae.

3.2. Airborne Setae Dispersion

3.2.1. Close Range, Circular Dispersion

Active and Passive Samplers:

Simulated Exposure of a Person (Dummy Experiment):

Setae Source Magnitude:

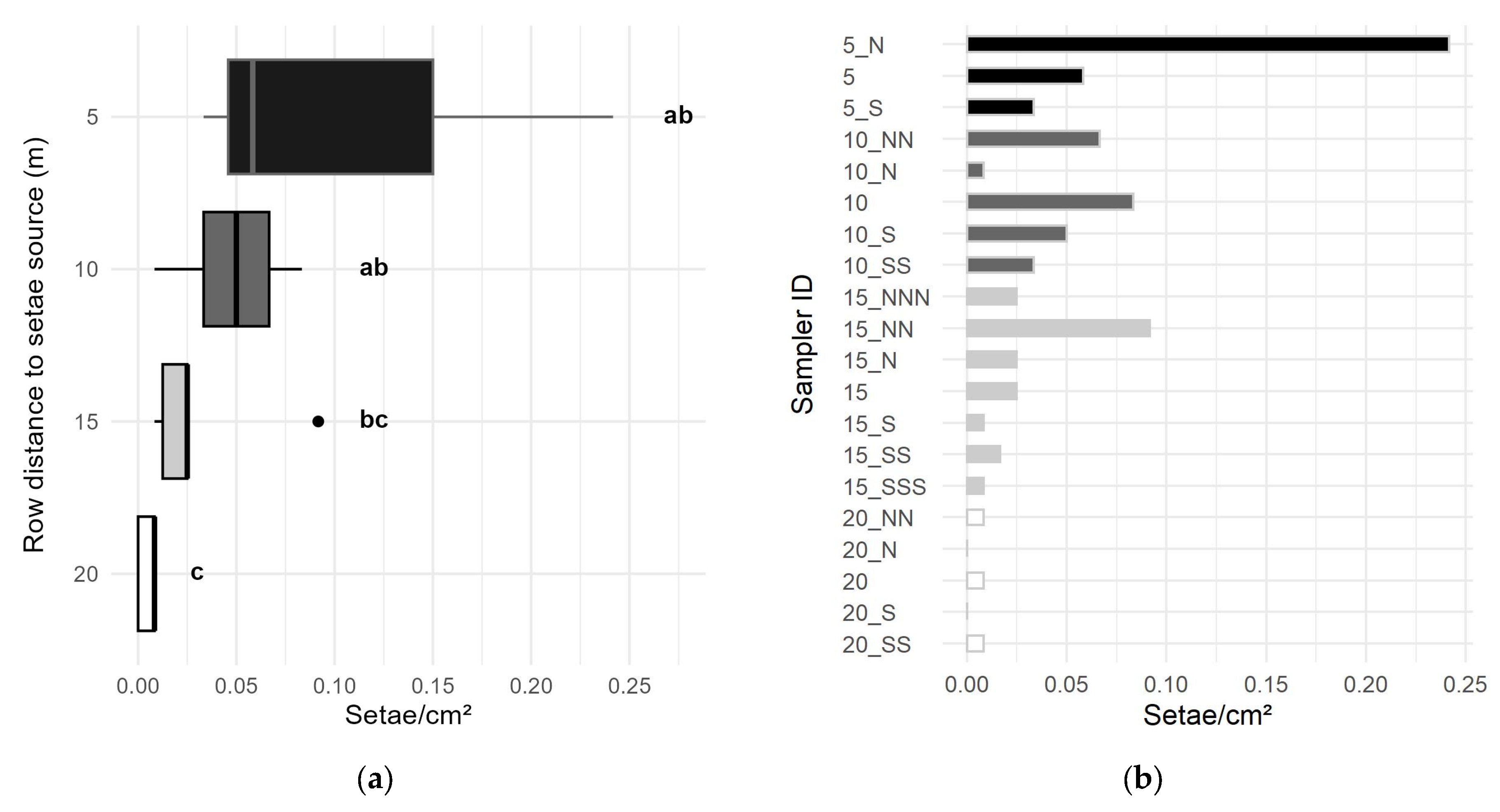

3.2.2. Horizontal Setae Dispersion

Setae Source Magnitude:

4. Discussion

4.1. Setae Quantification

4.2. Airborne Setae Dispersion

4.2.1. Close Range, Circular Dispersion

Active and Passive Samplers:

Simulated Exposure of a Person (Dummy Experiment):

4.2.2. Horizontal Setae Dispersion

4.2.3. Summary: Airborne Setae Dispersion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AS | Active sampler |

| AGL | Above ground level |

| BOKU | BOKU University (Universität für Bodenkultur Wien) |

| CEST | Central European Summer Time |

| d | Distance |

| d-l | Dorso-lateral mirror |

| DBH | Diameter at breast height |

| DWD | Deutscher Wetterdienst (German Meteorological Service) |

| f | Fore-mirror |

| FVA | Forest Research Institute Baden-Wuerttemberg (Forstliche Versuchs- und Forschungsanstalt Baden-Württemberg) |

| h | Hind-mirror |

| H | Horizontal |

| NA | Not available |

| n.r. | Not relevant |

| OPM | Oak processionary moth |

| PPM | Pine processionary moth |

| r | Radius |

| Ref. | Reference tent volume of 1 L |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SE | Standard error |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscope |

| V | Vertical |

References

- Basso, A.; Negrisolo, E.; Zilli, A.; Battisti, A.; Cerretti, P. A total evidence phylogeny for the processionary moths of the genus Thaumetopoea (Lepidoptera: Notodontidae: Thaumetopoeinae). Cladistics 2017, 33, 557–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battisti, A.; Larsson, S.; Roques, A. Processionary moths and associated urtication risk: Global change-driven effects. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2017, 62, 323–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, M. Report on survey for oak processionary moth Thaumetopoea processionea (Linnaeus) (Lepidoptera: Thaumetopoeidae) (OPM) in London in 2007. In Report to the Forestry Commission; Mark Townsend: Oxford, UK, 2008; pp. 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- Sands, R.J. The Population Ecology of Oak Processionary Moth. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Southampton, Southampton, UK, 2017. Available online: http://eprints.soton.ac.uk/id/eprint/427138 (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Stigter, H.; Romeijn, G. Thaumetopoea processionea observed locally in large numbers in the Netherlands after more than a century (Lepidoptera: Thaumetopoeidae). Entomol. Ber. 1992, 52, 66–69. [Google Scholar]

- Tomiczek, C.; Krehan, H. Zunehmende Probleme mit dem Eichenprozessionsspinner in Ostösterreich. Forstsch. Aktuell 2003, 29, 17–18. [Google Scholar]

- Wagenhoff, E.; Delb, H. Current status of Thaumetopoea processionea (L.) in South-Western Germany. Berichte Freibg. Forstl. Forsch. 2011, 89, 195–198. [Google Scholar]

- Groenen, F.; Meurisse, N. Historical distribution of the oak processionary moth Thaumetopoea processionea in Europe suggests recolonization instead of expansion. Agric. For. Entomol. 2012, 14, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasseur, P.; Sinno-Tellier, S.; Rousselet, J.; Langrand, J.; Roques, A.; Bloch, J.; Labadie, M. Human exposure to larvae of processionary moths in France: Study of symptomatic cases registered by the French poison control centres between 2012 and 2019. Clin. Toxicol. 2022, 60, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buist, Y.; Bekker, M.; Vaandrager, L.; Koelen, M.; van Mierlo, B. Strategies for public health adaptation to climate change in practice: Social learning in the Processionary Moth Knowledge Platform. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1179129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loock, B.; Lobinger, G. Der Eichenprozessionsspinner—Situation in Bayern und praxisnahe Forschung im Waldschutz [The oak processionary moth—The situation in Bavaria and scientific approach in forest protection]. Jahrb. Baumpflege 2016, 20, 83–98. [Google Scholar]

- Möller, K.; Heydeck, P.; Hielscher, K.; Pastowski, F.; Dahms, C.; Wenk, M.; Ebert, P.; Jacob, C.; Krüger, A. Blattfressende Insekten an Eiche und anderen Laubgehölzen. In Waldschutzbericht 2017; Landesbetrieb Forst Brandenburg, Landeskompetenzzentrum Forst Eberswalde, Eds.; Ministerium für Ländliche Entwicklung, Umwelt und Landwirtschaft des Landes Brandenburg: Eberswalde, Germany, 2017; pp. 7–9. [Google Scholar]

- Delb, H.; John, R.; Grüner, J.; Seitz, G.; Wußler, J. Biotische Schaderreger an Laubbäumen. In Waldzustandsbericht 2018 für Baden-Württemberg; Forstliche Versuchs- und Forschungsanstalt Baden-Württemberg, Ed.; Forstliche Versuchs- und Forschungsanstalt Baden-Württemberg: Freiburg im Breisgau, Germany, 2018; pp. 33–34. [Google Scholar]

- Hlásny, T.; Mátyás, C.; Seidl, R.; Kulla, L.; Merganičová, K.; Trombik, J.; Dobor, L.; Barcza, Z.; Konôpka, B. Climate change increases the drought risk in Central European forests: What are the options for adaptation? For. J. 2014, 60, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madrigal-González, J.; Ruiz-Benito, P.; Ratcliffe, S.; Rigling, A.; Wirth, C.; Zimmermann, N.E.; Zweifel, R.; Zavala, M.A. Competition drives oak species distribution and functioning in Europe: Implications under global change. In Oaks Physiological Ecology. Exploring the Functional Diversity of Genus Quercus L.; Gil-Pelegrín, E., Peguero-Pina, J.J., Sancho-Knapik, D., Eds.; Springer: Cham, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 513–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mölder, A.; Meyer, P.; Nagel, R.-V. Integrative management to sustain biodiversity and ecological continuity in Central European temperate oak (Quercus robur, Q. petraea) forests: An overview. For. Ecol. Manag. 2019, 437, 324–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, P.; Wang, T.; Van Vliet, A.J.H.; Skidmore, A.K.; van Aalst, M. Worsening of tree-related public health issues under climate change. Nat. Plants 2020, 6, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasper, J.; Weigel, R.; Walentowski, H.; Gröning, A.; Petritan, A.M.; Leuschner, C. Climate warming-induced replacement of mesic beech by thermophilic oak forests will reduce the carbon storage potential in aboveground biomass and soil. Ann. For. Sci. 2021, 78, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damestoy, T.; Jactel, H.; Belouard, T.; Schmuck, H.; Plomion, C.; Castagneyrol, B. Tree species identity and forest composition affect the number of oak processionary moth captured in pheromone traps and the intensity of larval defoliation. Agric. For. Entomol. 2020, 22, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidner, H. Belästigung von Menschen und Tieren durch die Raupen des Eichenprozessionsspinners Thaumetopoea processionea LINNAEUS 1758 (Lep., Thaumetopoeidae). Untere Havel—Naturkundliche Berichte 1994, 3, 34–42. [Google Scholar]

- Maier, H.; Spiegel, W.; Kinaciyan, T.; Krehan, H.; Cabaj, A.; Schopf, A.; Hönigsmann, H. The oak processionary caterpillar as the cause of an epidemic airborne disease: Survey and analysis. Br. J. Dermatol. 2003, 149, 990–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, H.; Spiegel, W.; Kinaciyan, T.; Hönigsmann, H. Caterpillar dermatitis in two siblings due to the larvae of Thaumetopoea processionea L.; the oak processionary caterpillar. Dermatology 2004, 208, 70–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenk, L.; Vogel, B.; Horvath, H. Dispersion of the bio-aerosol produced by the oak processionary moth. Aerobiologia 2007, 23, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, J.M.; Moneo, I.; García-Ortiz, J.C.; González-Muñoz, M.; Ruiz, C.; Rodríguez-Mahillo, A.I.; Roques, A.; Vega, J. IgE sensitization to Thaumetopoea pityocampa: Diagnostic utility of a setae extract, clinical picture and associated risk factors. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2015, 165, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, J.; Wenning, A.; Hentschel, R.; Möller, K. Rückkehr eines Provokateurs: Was steuert die Ausbreitungsdynamik des Eichenprozessionsspinners in Brandenburg?—Ergebnisse aus dem Waldklimafonds-Projekt “WAHYKLAS”. Eberswalder Forstl. Schriftenreihe 2016, 62, 77–88. [Google Scholar]

- Barthod, C.; Zmirou-Navier, D. Un tournant dans la prise en compte des arbres et des forêts en santé publique. Rev. For. Française 2018, 70, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thibaudon, M.; Besancenot, J.-P. Forêts et allergies. Rev. For. Française 2018, 70, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vornholt, C.-P. Verpflichtung zur Beseitigung von EPS-Gespinstnestern. AFZ-Der Wald 2020, 2, 34–35. [Google Scholar]

- Olivieri, M.; Ludovico, E.; Battisti, A. Occupational exposure of forest workers to the urticating setae of the pine processionary moth Thaumetopoea pityocampa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crandall-Stotler, B.J.; Bartholomew-Began, S.E. Morphology of mosses (phylum Bryophyta). Flora N. Am. N. Mex. 2007, 27, 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Antonín, V.; Ryoo, R.; Ka, K.H. Marasmioid and gymnopoid fungi of the Republic of Korea. 7. Gymnopus sect. Androsacei. Mycol. Prog. 2014, 13, 703–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owari, Y.; Nakamura, F.; Oaki, Y.; Tsuda, H.; Shimode, S.; Imai, H. Ultrastructure of setae of a planktonic diatom, Chaetoceros coarctatus. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 7568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouau, Y. Comparison of crustacean and insect mechanoreceptive setae. Int. J. Insect Morphol. Embryol. 1997, 26, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, A.; Karg, W. A revised setal nomenclature based on ontogenetic and phylogenetic characters and universally applicable to the idiosoma of Gamasina (Acari, Parasitiformes). Soil Org. 2008, 80, 45. [Google Scholar]

- Winterton, S.L. Scales and setae. In Encyclopedia of Insects; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009; pp. 901–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertani, R.; Guadanucci, J.P.L. Morphology, evolution and usage of urticating setae by tarantulas (Araneae: Theraphosidae). Zoologia 2013, 30, 403–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Marcos Fu, H.C. How the bending mechanics of setae modulate hydrodynamic sensing in copepods. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2020, 65, 749–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, A.M.; Russell, A.P. Revisiting the classification of squamate adhesive setae: Historical, morphological and functional perspectives. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2021, 8, 202039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niederegger, S.; Gorb, S.; Jiao, Y. Contact behaviour of tenent setae in attachment pads of the blowfly Calliphora vicina (Diptera, Calliphoridae). J. Comp. Physiol. A 2002, 187, 961–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battisti, A.; Holm, G.; Fagrell, B.; Larsson, S. Urticating hairs in arthropods: Their nature and medical significance. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2011, 56, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werno, J.; Lamy, M. Daily cycles for emission of urticating hairs from the pine processionary caterpillar (Thaumetopoea pityocampa S.) and the brown tail moth (Euproctis chrysorrhoea L.) (Lepidoptera) in laboratory conditions. Aerobiologia 1994, 10, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berardi, L.; Battisti, A.; Negrisolo, E. The allergenic protein Tha p 2 of processionary moths of the genus Thaumetopoea (Thaumetopoeinae, Notodontidae, Lepidoptera): Characterization and evolution. Gene 2015, 574, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battisti, A.; Walker, A.A.; Uemura, M.; Zalucki, M.P.; Brinquin, A.-S.; Caparros-Megidos, R.; Gachet, E.; Kerdelhué, C.; Desneux, N. Look but do not touch: The occurrence of venomous species across Lepidoptera. Entomol. Gen. 2024, 44, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gäbler, H. Die Prozessionsspinner; A. Ziemsen Verlag: Wittenberg, Germany, 1954; pp. 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Démolin, G. Les “miroirs” urticants de la processionnaire du pin (Thaumetopoea pityocampa Schiff.). Rev. Zool. Agric. Appliquée 1963, 10, 107–114. [Google Scholar]

- Plugaru, S.G. The biology of the oak processionary moth in Moldavia. Vrednaja Polezn. Fauna Bespozvononych Mold. 1968, 3, 29–41. [Google Scholar]

- Lamy, M. Contact dermatitis (erucism) produced by processionary caterpillars (Genus Thaumetopoea). J. Appl. Entomol. 1990, 110, 425–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, A.A.; Perkins, L.E.; Battisti, A.; Zalucki, M.P.; King, G.F. Proteome of urticating setae of Ochrogaster lunifer, a processionary caterpillar of medical and veterinary importance, including primary structures of putative toxins. Proteomics 2023, 23, e2300204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrucco Toffolo, E.; Zovi, D.; Perin, C.; Paolucci, P.; Roques, A.; Battisti, A.; Horvath, H. Size and dispersion of urticating setae in three species of processionary moths. Integr. Zool. 2014, 9, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbaro, L.; Battisti, A. Birds as predators of the pine processionary moth (Lepidoptera: Notodontidae). Biol. Control 2011, 56, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobczyk, T. Der Eichenprozessionsspinner in Deutschland: Historie—Biologie—Gefahren—Bekämpfung. In BfN-Skripten, 365; Bundesamt für Naturschutz, Ed.; Bundesamt für Naturschutz: Bonn, Germany, 2014; pp. 46–47. [Google Scholar]

- Mühlfeit, M.; Rumpf, S.; Rohde, M.; Plašil, P.; Sennhenn-Reulen, H. Erhebung Wichtiger Phänologischer Daten und Korrespondierender Populationsdichten des Eichenprozessionsspinners (Thaumetopoea processionea L.) Sowie Untersuchung des Einflusses Seiner Natürlichen Gegenspieler Unter Unterschiedlichen Klimatischen Bedingungen in Verschiedenen Regionen Deutschlands im Rahmen des Verbundvorhabens “Modellgestützte Gefährdungsabschätzung des Eichenprozessionsspinners im Klimawandel (ModEPSKlim)”. Schlussbericht zum Teilprojekt 2A.; Nordwestdeutsche Forstliche Versuchsanstalt, Ed.; Nordwestdeutsche Forstliche Versuchsanstalt: Göttingen, Germany, 2021; pp. 43–44. Available online: https://projekte.fnr.de/index.php?id=18415&fkz=22WC409002 (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Pascual, J.A. Biología de la Procesionaria del roble (Thaumetopoea processionea L.) (Lep. Thaumetopoeidae) en el centro-oeste de la Península Ibérica. Boletín de sanidad vegetal. Plagas 1988, 14, 383–404. [Google Scholar]

- Wagenhoff, E.; Veit, H. Five years of continuous Thaumetopoea processionea monitoring: Tracing population dynamics in an arable landscape of South-Western Germany. Gesunde Pflanz. 2011, 63, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klapwijk, M.J.; Csóka, G.; Hirka, A.; Björkman, C. Forest insects and climate change: Long-term trends in herbivore damage. Ecol. Evol. 2013, 3, 4183–4196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagenhoff, E.; Wagenhoff, A.; Blum, R.; Veit, H.; Zapf, D.; Delb, H. Does the prediction of the time of egg hatch of Thaumetopoea processionea (Lepidoptera: Notodontidae) using a frost day/temperature sum model provide evidence of an increasing temporal mismatch between the time of egg hatch and that of budburst of Quercus robur due to recent global warming? Eur. J. Entomol. 2014, 111, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbig, P.; Stelzer, A.-S.; Baier, P.; Pennerstorfer, J.; Delb, H.; Schopf, A. PHENTHAUproc-An early warning and decision support system for hazard assessment and control of oak processionary moth (Thaumetopoea processionea). For. Ecol. Manag. 2024, 552, 121525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheidter, F. Auftreten der “Gifthaare” bei den Prozessionsspinnerraupen in den einzelnen Stadien. Pflanzenkrankh. Pflanzenschutz 1934, 44, 223–226. [Google Scholar]

- Lamy, M. Chenilles et papillons urticants: Une “pollution” méconnue. La Rech. 1990, 21, 896–900. [Google Scholar]

- Ducombs, G.; Lamy, M.; Bergaud, J.J.; Tamisier, J.M.; Gervais, C.; Texier, L. La chenille processionnaire. Enquête épidémiologique. Ann. Dermatol. Vénéréologie 1979, 106, 769–778. [Google Scholar]

- Lamy, M.; Ducombs, M.; Pastureaud, M.-H.; Vincendeau, P. Productions tégumentaires de la processionnaire du pin (Thaumetopoea pityocampa Schiff.) (Lépidoptères). Appar. Urticant Appar. Ponte. Bull. Société Zool. Fr. 1982, 107, 515–529. [Google Scholar]

- Stigter, H.; Geraedts, W.H.J.M.; Spijkers, H.C.P. Thaumetopoea processionea in the Netherlands: Present status and management perspectives (Lepidoptera: Notodontidae). Proc. Sect. Exp. Appl. Entomol. Neth. Entomol. Soc. 1997, 8, 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Battisti, A.; Paolucci, P.; Petrucco Toffolo, E.; Roques, A. Comparative structure of the urticating apparatus in processionary moths. In Processionary Moths and Climate Change: An Update; Roques, A., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 360–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamy, M.; Novak, F.; Duboscq, M.F.; Ducombs, G.; Maleville, J. La chenille processionnaire du chêne (Thaumetopoea processionea L.) et l’homme: Appareil urticant et mode d’action. Ann. Dermatol. Vénéréologie 1988, 115, 1023–1032. [Google Scholar]

- Vega, J.; Vega, J.M.; Moneo, I.; Armentia, A.; Caballero, M.L.; Miranda, A. Occupational immunologic contact urticaria from pine processionary caterpillar (Thaumetopoea pityocampa): Experience in 30 cases. Contact Dermat. 2004, 50, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagrell, B.; Jörneskog, G.; Salomonsson, A.C.; Larsson, S.; Holm, G.R. Skin reactions induced by experimental exposure to setae from larvae of the northern pine processionary moth (Thaumetopoea pinivora). Contact Dermat. 2008, 59, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenk, L. Die Atmosphärische Ausbreitung der Brennhärchen des Eichenprozessionsspinners. Diploma Thesis, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Mahillo, A.I.; González-Muñoz, M.; Vega, J.M.; López, J.A.; Yart, A.; Kerdelhué, C.; Camafeita, E.; Garcia Ortiz, J.C.; Vogel, H.; Petrucco Toffolo, E.; et al. Setae from the pine processionary moth (Thaumetopoea pityocampa) contain several relevant allergens. Contact Dermat. 2012, 67, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seldeslachts, A.; Maurstad, M.F.; Øyen, J.P.; Undheim, E.A.B.; Peigneur, S.; Tytgat, J. Exploring oak processionary caterpillar induced lepidopterism (Part 1): Unveiling molecular insights through transcriptomics and proteomics. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2024, 81, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamy, M.; Pastureaud, M.H.; Novak, F.; Ducombs, G.; Vincedeau, P.; Maleville, J.; Texier, L. Thaumetopoein: An urticating protein from the hairs and integument of the pine processionary caterpillar (Thaumetopoea pityocampa Schiff., Lepidoptera, Thaumetopoeidae). Toxicon 1986, 24, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, F.; Pelissou, V.; Lamy, M. Comparative morphological, anatomical and biochemical studies of the urticating apparatus and urticating hairs of some Lepidoptera: Thaumetopoea pityocampa Schiff., Th. processionea L. (Lepidoptera, Thaumetopoeidae) and Hylesia metabus Cramer (Lepidoptera, Saturniidae). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A 1987, 88, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moneo, I.; Vega, J.M.; Caballero, M.L.; Vega, J.; Alday, E. Isolation and characterization of Tha p 1, a major allergen from the pine processionary caterpillar Thaumetopoea pityocampa. Allergy 2003, 58, 34–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Mahillo, A.I.; Carballeda-Sangiao, N.; Vega, J.M.; García-Ortiz, J.C.; Roques, A.; Moneo, I.; González-Muñoz, M. Diagnostic use of recombinant Tha p 2 in the allergy to Thaumetopoea pityocampa. Allergy 2015, 70, 1332–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hase, A. Über den Pinienprozessionsspinner und über die Gefährlichkeit seiner Raupenhaare. (Thaumetopoea pityocampa Schiff.). Anz. Für Schädlingskunde 1939, 15, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maronna, A.; Stache, H.; Sticherling, M. Lepidopterism—Oak processionary caterpillar dermatitis: Appearance after indirect out-of-season contact. J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 2008, 6, 747–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perkins, L.E.; Zalucki, M.P.; Perkins, N.R.; Cawdell-Smith, A.J.; Todhunter, K.H.; Bryden, W.L.; Cribb, B.W. The urticating setae of Ochrogaster lunifer, an Australian processionary caterpillar of veterinary importance. Med. Vet. Entomol. 2016, 30, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uemura, M.; Perkins, L.E.; Zalucki, M.P.; Battisti, A. Movement behaviour of two social urticating caterpillars in opposite hemispheres. Mov. Ecol. 2020, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werno, J.; Lamy, M. Atmospheric pollution of animal origin: The urticating hairs of the processionary caterpillar (Thaumetopoea pityocampa Schiff.) (Insects, Lepidoptera). Comptes Rendus L’académie Sciences. Série III Sci. Vie 1990, 310, 325–331. [Google Scholar]

- Forkel, S.; Mörlein, J.; Sulk, M.; Beutner, C.; Rohe, W.; Schön, M.P.; Geier, J.; Buhl, T. Work-related hazards due to oak processionary moths: A pilot survey on medical symptoms. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2021, 35, e779–e782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.K.H.; Jalink, M.B.; Sint Jago, N.F.M.; Ho, L.; Arnold van Vliet, J.H.; Das, T.; de Faber, J.T.H.N.; Wisse, R.P.L. Ocular complications of oak processionary caterpillar setae in the Netherlands; case series, literature overview, national survey and treatment advice. Acta Ophthalmol. 2021, 99, 452–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seldeslachts, A.; Undheim, E.A.B.; Vriens, J.; Tytgat, J.; Peigneur, S. Exploring oak processionary caterpillar induced lepidopterism (part 2): Ex vivo bio-assays unmask the role of TRPV1. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2024, 81, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebollo, S.; Moneo, I.; Vega, J.M.; Herrera, I.; Caballero, M.L. Pine processionary caterpillar allergenicity increases during larval development. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2002, 128, 310–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos-Magadán, S.; González de Olano, D.; Bartolomé-Zavala, B.; Trujillo-Trujillo, M.; Meléndez-Baltanás, A.; González-Mancebo, E. Adverse reactions to the processionary caterpillar: Irritant or allergic mechanism? Contact Dermat. 2009, 60, 109–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikolov, G.; Kandova, Y.; Petrunov, B.; Mirchev, P.; Georgiev, G. Skin reactions to allergens from processionary caterpillars (genus Thaumetopoea). Probl. Infect. Parasit. Dis. 2020, 48, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renström, A. Exposure to airborne allergens: A review of sampling methods. J. Environ. Monit. 2002, 4, 619–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrnsperger, A. Fallstudie über die Emission von Gifthärchen aus Waldbeständen mit Eichenprozessionsspinner-Befall. Bachelor’s Thesis, University of Applied Sciences Weihenstephan-Triesdorf, Freising, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hirst, J.M. An automatic volumetric spore trap. Ann. Appl. Biol. 1952, 39, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkard Manufacturing Co., Ltd. Seven-day recording volumetric spore trap. 2025. Available online: https://burkard.co.uk/product/7-day-recording-volumetric-spore-trap/ (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Roques, L.; Soubeyrand, S.; Garnier, J.; Battisti, A.; Robinet, C.; Roques, A.; Rousselet, J. URTIRISK Software. 2013. Available online: https://biosp.mathnum.inrae.fr/URTIRISK (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- DWD—Deutscher Wetterdienst. Eichenprozessionsspinner-Frühwarnsystem. 2025. Available online: https://www.dwd.de/eichenprozessionsspinner (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Delb, H.; Halbig, P.; Seitz, G.; Wagenhoff, E. Der Eichenprozessionsspinner als Profiteur des Klimawandels: Müssen Baum und Mensch mit dieser Gefahr leben? Jahrb. Baumpflege 2019, 23, 201–213. [Google Scholar]

- Klapwijk, M.J.; Walter, J.A.; Hirka, A.; Csóka, G.; Björkman, C.; Liebhold, A.M. Transient synchrony among populations of five foliage-feeding Lepidoptera. J. Anim. Ecol. 2018, 87, 1058–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzano, M.; Ambrose-Oji, B.; Hall, C.; Moseley, D. Pests in the city: Managing public health risks and social values in response to oak processionary moth (Thaumetopoea processionea) in the United Kingdom. Forests 2020, 11, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPPO; European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization. EPPO Standard on phytosanitary procedures. EPPO Bull. 2022, 52, 572–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, I.; Potter, C.; Bayliss, H. Managing tree pests and diseases in urban settings: The case of oak processionary moth in London, 2006–2012. Urban For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 286–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dissescu, G.; Ceianu, I. Cercetari Asupra Bioecologiei Omizii Procesionare a Stejarului (Thaumetopoea processionea L.); Ministerul Economiei Forestiere, Institutul de Cercetari Forestiere: Bucureşti, Romania, 1968; pp. 13–14. [Google Scholar]

- Mosteller, R.D. Simplified calculation of body-surface area. N. Engl. J. Med. 1987, 317, 1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangiafico, S.S. Rcompanion: Functions to Support Extension Education Program Evaluation, Version 2.5.0.; Rutgers Cooperative Extension: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 2025; Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rcompanion (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Ogle, D.H.; Doll, J.C.; Wheeler, A.P.; Dinno, A. FSA: Simple Fisheries Stock Assessment Methods, Version 0.10.0.; R Studio: Boston, MA, USA, 2025; Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=FSA (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Buist, Y.; Bekker, M.; Vaandrager, L.; Koelen, M. Understanding public health adaptation to climate change: An explorative study on the development of adaptation strategies relating to the oak processionary moth in the Netherlands. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, D.B. Workbook of Atmospheric Dispersion Estimates; United States Environmental Protection Agency: Research Triangular Park, NC, USA, 1970; pp. 7–10.

- Forestry Commission. OPM Resource Hub. Department for Environment 2025, Food and Rural Affairs. Available online: https://opmhub.fera.co.uk/ (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Straw, N.A.; Hoppit, A.; Branson, J. The relationship between pheromone trap catch and local population density of the oak processionary moth Thaumetopoea processionea (Lepidoptera: Thaumetopoeidae). Agric. For. Entomol. 2019, 21, 424–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschmann, V.; Lobinger, G. Adaptives Risikomanagement in trockenheitsgefährdeten Eichen- und Kiefernwäldern mit Hilfe integrativer Bewertung und angepasster Schadschwellen (ARTEMIS): Waldschutzrisikomanagement mit variablen Schadschwellen für ausgewählte Bestandesschädlinge der Eiche in Süddeutschland. Schlussbericht zum Teilvorhaben 4. Bayerische Landesanstalt für Wald und Forstwirtschaft, Ed. 2023. Available online: https://projekte.fnr.de/index.php?id=18415&fkz=22020618 (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Williams, D.T.; Straw, N.; Townsend, M.; Wilkinson, A.S.; Mullins, A. Monitoring oak processionary moth Thaumetopoea processionea L. using pheromone traps: The influence of pheromone lure source, trap design and height above the ground on capture rates. Agric. For. Entomol. 2013, 15, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roversi, P.F. Aerial spraying of Bacillus thuringiensis var. kurstaki for the control of Thaumetopoea processionea in Turkey oak woods. Phytoparasitica 2008, 36, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habermann, M. Abschätzung von Schad- und Bekämpfungsschwellen beim Eichenprozessionsspinner. AFZ-Der Wald 2012, 67, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Keena, M.A.; Vandel, A.; Pultar, O. Phenology of Lymantria monacha (Lepidoptera: Lymantriidae) laboratory reared on spruce foliage or a newly developed artificial diet. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 2010, 103, 949–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergomaz, R.; Boppré, M. A simple instant diet for rearing Arctiidae and other moths. J. Lepid. Soc. 1986, 40, 131–137. [Google Scholar]

| Measuring Position | Wind Speed (m/s) During the Experiment | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 16:15 (Start) | 16:35 | 16:55 | |

| Blower orifice | 12.50 | NA | NA |

| Before mesh bag (setae source) | 9.21 | 9.16 | 8.26 |

| Behind mesh bag (setae source) | 1.75 | 1.87 | 1.87 |

| Samplers ID 3, 4, 7, 9, 14, 16, 18, 20 | 0.00 | NA | NA |

| Sampler ID 5 | 0.87 | 1.10 | 0.86 |

| Samplers ID 6, 17 | 0.70 | NA | NA |

| OPM Sample | Segments (Mirrors) | Area (mm2) | Setae/mm2 | Setae/Larva | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Instar | ID | Origin | Dense | Wide | Total | Dense | Wide | Dense | Wide | Total | |

| L3 | 1 | Freiburg semi-field | 11 (f, h) | 0.074 | Non-existent | 0.074 | 40,145 | Non-existent | 2987 | Non-existent | 2987 |

| 2 | 0.058 | 0.058 | 31,400 | 1808 | 1808 | ||||||

| 3 | 0.041 | 0.041 | 49,120 | 2032 | 2032 | ||||||

| 4 | 0.049 | 0.049 | 44,978 | 2201 | 2201 | ||||||

| 5 | 0.040 | 0.040 | 56,640 | 2273 | 2273 | ||||||

| L4 | 6 | Freiburg field | 10 (h), 11 (f, h) | 0.159 | 0.040 | 0.198 | 47,171 | 24,793 | 7482 | 983 | 8465 |

| 7 | 0.178 | 0.044 | 0.222 | 44,722 | 33,571 | 7957 | 1493 | 9451 | |||

| 8 | 0.131 | 0.033 | 0.164 | 39,700 | 28,114 | 5207 | 922 | 6129 | |||

| 9 | Freiburg semi-field | 0.102 | 0.025 | 0.127 | 38,400 | 27,200 | 3916 | 693 | 4610 | ||

| 10 | 0.097 | 0.024 | 0.121 | 42,982 | 32,000 | 4156 | 774 | 4930 | |||

| L5 | 11 | Freiburg field | 4-10 (h), 11 (f, h), [4-10 (f), 11 (d-l)] ‡ | 0.699 | 0.078 | 0.777 | 47,618 | 30,800 | 33,294 | 2395 | 35,690 |

| 12 | 0.816 | 0.047 | 0.864 | 47,190 | 25,067 | 38,528 | 1189 | 39,718 | |||

| 13 | 0.960 | 0.053 | 1.013 | 48,108 | 33,600 | 46,170 | 1793 | 47,963 | |||

| 14 | Lorraine field | 1.202 | 0.121 | 1.323 | 47,086 | 28,036 | 56,600 | 3392 | 59,992 | ||

| 15 | Freiburg semi-field | 0.404 | 0.060 | 0.464 | 54,479 | 46,488 | 22,017 | 2775 | 24,791 | ||

| L6 | 16 | Mengen field | 4-10 (f, h), 11 (f, h, d-l), 12 (f), [6, 9, 10 (d-l)] ‡ | 12.419 | 1.215 | 13.635 | 60,804 | 39,408 | 755,155 | 47,889 | 803,044 |

| 17 | 12.231 | 0.829 | 13.059 | 61,829 | 42,367 | 756,198 | 35,119 | 791,317 | |||

| 18 | 16.869 | 0.569 | 17.438 | 47,536 | 36,158 | 801,896 | 20,567 | 822,463 | |||

| 19 | Freiburg semi-field | 2.731 | 1.009 | 3.740 | 51,053 | 36,227 | 139,410 | 36,563 | 175,973 | ||

| 20 | 7.906 | 0.275 | 8.182 | 45,492 | 30,375 | 359,674 | 8366 | 368,040 | |||

| OPM Sample | Area (mm2) | Setae/mm2 | Setae/Larva | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dense | Wide | ||||||||||

| Instar | ID | Origin | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | % |

| L3 | 1 | Freiburg semi-field | 0.052 | 0.013 | 44,457 | 8480 | NA | NA | 2260 | 397 | 0.3 |

| 2 | |||||||||||

| 3 | |||||||||||

| 4 | |||||||||||

| 5 | |||||||||||

| L4 | 6 | Freiburg field | 0.195 | 0.024 | 43,865 | 3110 | 28,826 | 3619 | 8015 | 1393 | 0.9 |

| 7 | |||||||||||

| 8 | |||||||||||

| L5 | 11 | Freiburg field | 0.885 | 0.097 | 47,639 | 375 | 29,822 | 3552 | 41,123 | 5108 | 4.8 |

| 12 | |||||||||||

| 13 | |||||||||||

| L6 | 16 | Mengen field | 14.711 | 1.943 | 56,723 | 6510 | 39,311 | 2535 | 805,608 | 12,844 | 94.0 |

| 17 | |||||||||||

| 18 | |||||||||||

| Total | 857,006 * | 100.0 | |||||||||

| Level | Size Class | Tent Volume (L) | Loose Tents | Compact Tents | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individuals | Setae (Million) | Individuals | Setae (Million) | |||

| OPM colony (tent) | Ref. | 1.0 | 400 | 343 | 1000 | 857 |

| Small | 0.2 | 80 | 69 | 200 | 171 | |

| Medium | 3.0 | 1200 | 1028 | 3000 | 2571 | |

| Large | 6.0 | 2400 | 2057 | 6000 | 5142 | |

| Extra-large | 12.0 | 4800 | 4114 | 12,000 | 10,284 | |

| Whole tree | CI lower limit | 21.0 | 8400 | 7200 | 21,000 | 18,000 |

| Mean | 28.0 | 11,200 | 9600 | 28,000 | 24,000 | |

| CI upper limit | 36.0 | 14,400 | 12,900 | 36,000 | 30,900 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Halbig, P.; Delb, H.; Schopf, A. Quantification of Urticating Setae of Oak Processionary Moth (Thaumetopoea processionea) and Exposure Hazards. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1361. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091361

Halbig P, Delb H, Schopf A. Quantification of Urticating Setae of Oak Processionary Moth (Thaumetopoea processionea) and Exposure Hazards. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(9):1361. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091361

Chicago/Turabian StyleHalbig, Paula, Horst Delb, and Axel Schopf. 2025. "Quantification of Urticating Setae of Oak Processionary Moth (Thaumetopoea processionea) and Exposure Hazards" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 9: 1361. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091361

APA StyleHalbig, P., Delb, H., & Schopf, A. (2025). Quantification of Urticating Setae of Oak Processionary Moth (Thaumetopoea processionea) and Exposure Hazards. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(9), 1361. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091361