Social Network Impacts and Moderators of Depression Among Indigenous Maya People Remaining in Place of Origin in the Migrant-Sending Guatemalan Western Highlands

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Social Network Effects

1.2. Mental Health in Guatemala

1.3. Gendered Effects

1.4. Historical Context

1.5. Theoretical Basis

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Exposure and Outcome Variables

2.3. Analysis

3. Results

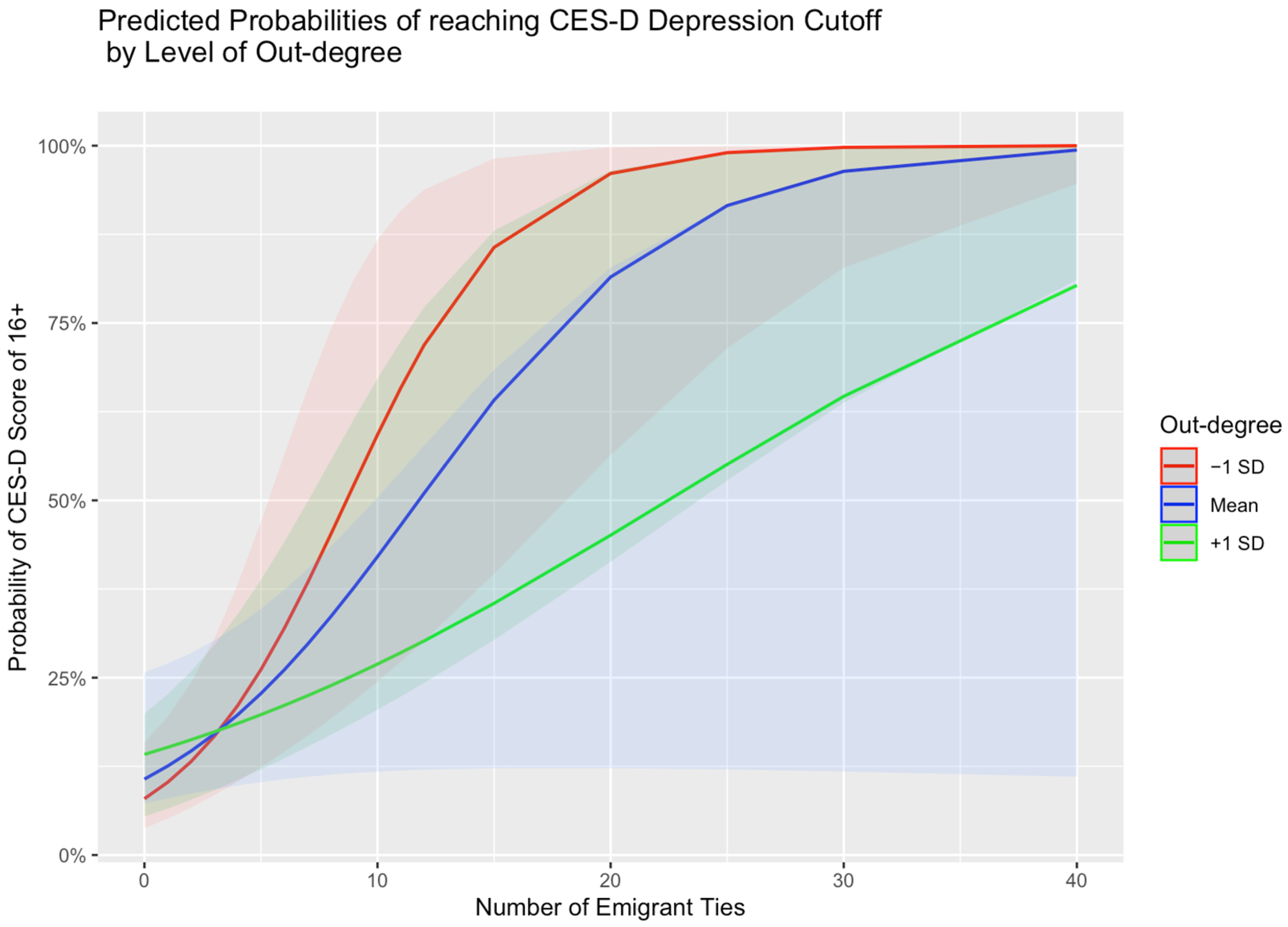

3.1. Aim 1: Emigrant Ties and Depressive Symptoms

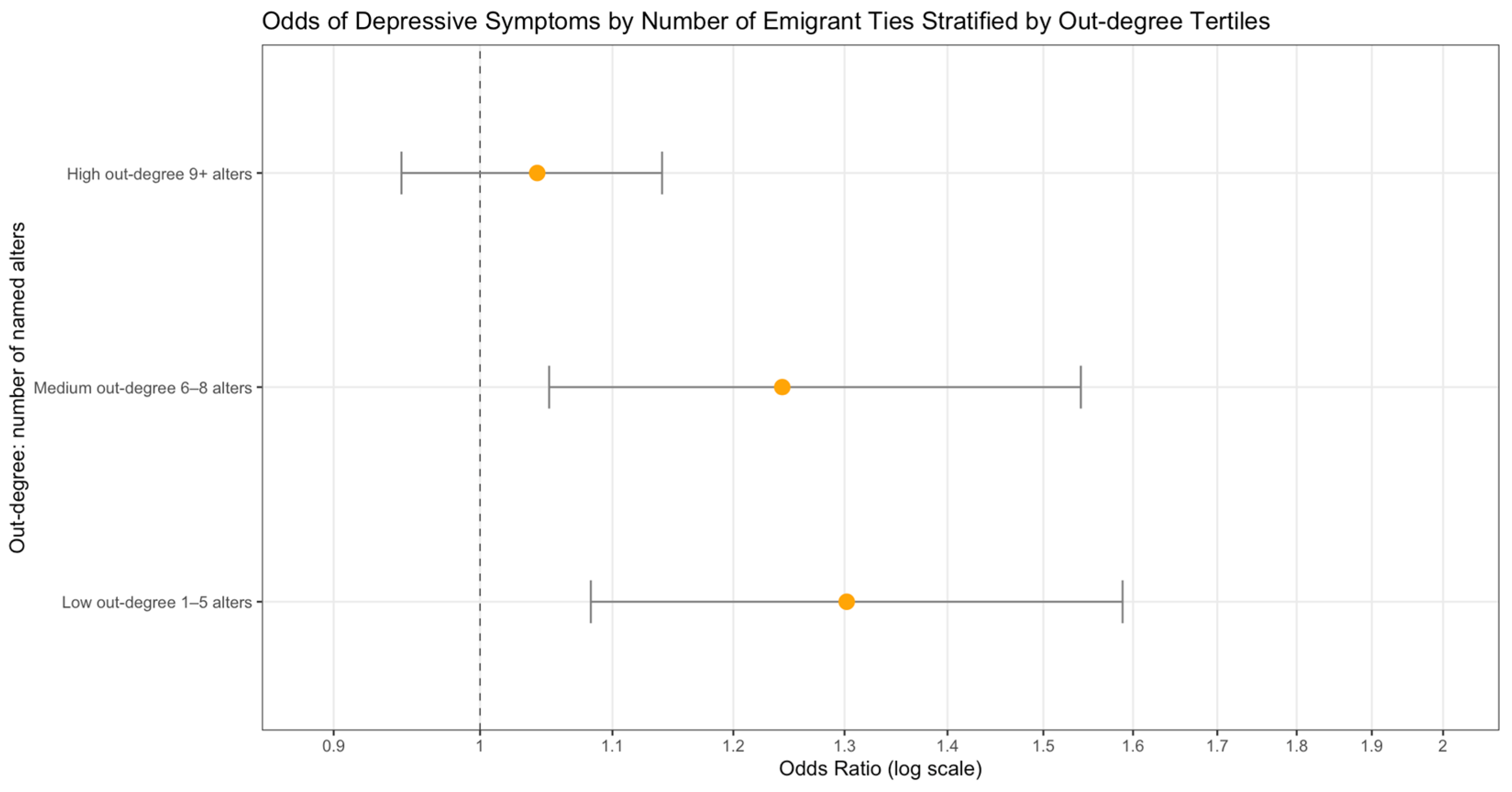

3.2. Aim 2: Moderation Effects

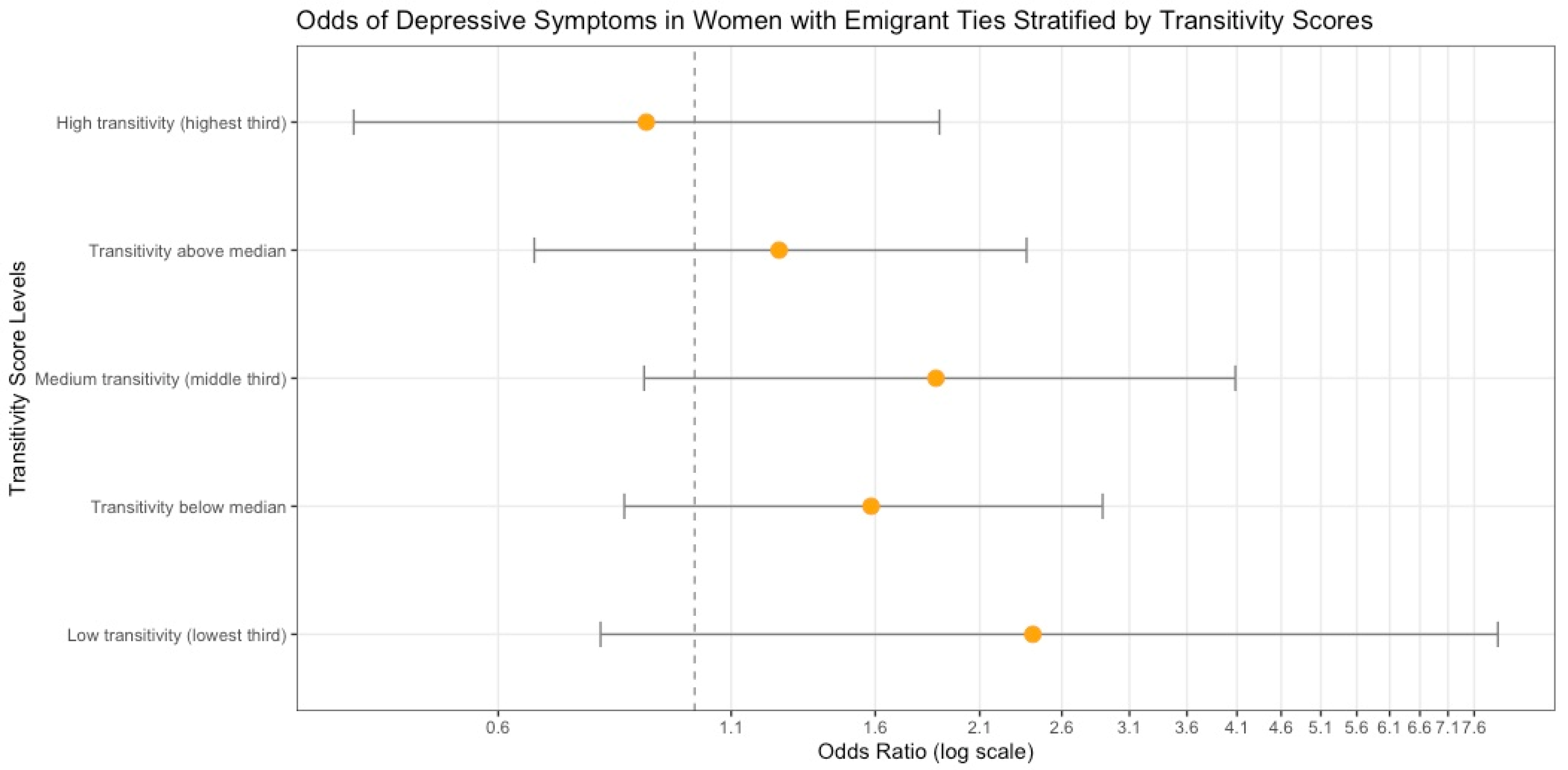

3.3. Differences by Sex

4. Discussion

4.1. Depression in the Rural Highlands

4.2. Aim 1: Emigrant Ties and Depression

4.3. Aim 2: Social Network Characteristics as “Buffers” to Depression

4.4. Gendered Differences in Network “Buffering”

4.5. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CES-D | Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression scale |

| CEH | Comisión para el Esclarecimiento Histórico |

| GLM | Generalized Linear Regression |

| HCHS/SOL | Hispanic Community Health Survey/Study of Latinos |

References

- Nobles, J.; Rubalcava, L.; Teruel, G. After spouses depart: Emotional wellbeing among nonmigrant Mexican mothers. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 132, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Withers, M.; Piper, N. Uneven development and displaced care in Sri Lanka. Curr. Sociol. 2018, 66, 590–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viet Nguyen, C. Does parental migration really benefit left-behind children? Comparative evidence from Ethiopia, India, Peru and Vietnam. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 153, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickramage, K.; Siriwardhana, C.; Vidanapathirana, P.; Weerawarna, S.; Jayasekara, B.; Pannala, G.; Adikari, A.; Jayaweera, K.; Peiris, S.; Siribaddana, S.; et al. Risk of mental health and nutritional problems for left-behind children of international labor migrants. BMC Psychiatry 2015, 15, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadi, A. Overseas migration and the well-being of those left behind in rural communities of Bangladesh. Asia Pac. Popul. J. 1999, 14, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acedera, K.A.; Yeoh, B.S.A. ‘Making time’: Long-distance marriages and the temporalities of the transnational family. Curr. Sociol. 2019, 67, 250–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, E.; Jordan, L.P.; Yeoh, B.S.A. Parental migration and the mental health of those who stay behind to care for children in South-East Asia. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 132, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzucato, V.; Cebotari, V.; Veale, A.; White, A.; Grassi, M.; Vivet, J. International parental migration and the psychological well-being of children in Ghana, Nigeria, and Angola. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 132, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.B.; Cebotari, V. Experiences of migration, parent-child interaction, and the life satisfaction of children in Ghana and China. Popul. Space Place 2018, 24, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, H.; Hu, J. Psychological resilience moderates the impact of social support on loneliness of “left-behind” children. J. Health Psychol. 2016, 21, 1066–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, X.Y.; Li, X.Y.; Ye, Z.; Li, Y.X.; Lin, D.H. Subjective well-being among left-behind children in rural China: The role of ecological assets and individual strength. Child Care Health Dev. 2019, 45, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, Q.; Chu, R.X. Anxiety, happiness and self-esteem of western Chinese left-behind children. Child Abus. Negl. 2018, 86, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Li, L.P.; Kim, J.H.; Congdon, N.; Lau, J.; Griffiths, S. The impact of parental migration on health status and health behaviours among left behind adolescent school children in China. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Chen, L.; Wang, X.H.; Liu, Y.; Chui, C.H.K.; He, H.A.; Qu, Z.Y.; Tian, D.H. The Relationship Between Internet Addiction and Depression Among Migrant Children and Left-Behind Children in China. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2012, 15, 585–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanore, M.; Mazzucato, V.; Siegel, M. ‘Left behind’ but not left alone: Parental migration & the psychosocial health of children in Moldova. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 132, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waidler, J.; Vanore, M.; Gassmann, F.; Siegel, M. Does it matter where the children are? The wellbeing of elderly people ‘left behind’ by migrant children in Moldova. Ageing Soc. 2017, 37, 607–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, S.; Martin, K. Fractured migrant families—Paradoxes of hope and devastation. Fam. Community Health 2007, 30, 178–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miltiades, H.B. The social and psychological effect of an adult child’s emigration on non-immigrant Asian Indian elderly parents. J. Cross Cult. Gerontol. 2002, 17, 33–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugargol, A.P.; Bailey, A. Family caregiving for older adults: Gendered roles and caregiver burden in emigrant households of Kerala, India. Asian Popul. Stud. 2018, 14, 194–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Hu, P.F.; Treiman, D.J. Migration and depressive symptoms in migrant-sending areas: Findings from the survey of internal migration and health in China. Int. J. Public Health 2012, 57, 691–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, A.B.I.; Tan-Mansukhani, R.; Daganzo, M.A.A. Associations Between Materialism, Gratitude, and Well-Being in Children of Overseas Filipino Workers. Eur. J. Psychol. 2018, 14, 581–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luot, N.V.; Dat, N.B.; Lam, T.Q. Subjective Well-Being among “Left-Behind Children” Of Labour Migrant Parents in Rural Northern Vietnam. Pertanika J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2018, 26, 1529–1545. [Google Scholar]

- Yamada, K.; Teerawichitchainan, B. Living Arrangements and Psychological Well-Being of the Older Adults After the Economic Transition in Vietnam. J. Gerontol. Ser. B-Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2015, 70, 957–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, C.; Oyserman, D. Left behind or moving forward? Effects of possible selves and strategies to attain them among rural Chinese children. J. Adolesc. 2015, 44, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guang, Y.; Feng, Z.Z.; Yang, G.Y.; Yang, Y.L.; Wang, L.F.; Dai, Q.; Hu, C.B.; Liu, K.Y.; Zhang, R.; Xia, F.; et al. Depressive symptoms and negative life events: What psycho-social factors protect or harm left-behind children in China? BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomșa, R.; Jenaro, C. Children left behind in Romania: Anxiety and predictor variables. Psychol. Rep. 2015, 116, 485–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, C.E.; Gorman, B.K.; Chavez, S. Exposure to Violence, Coping Strategies, and Diagnosed Mental Health Problems Among Adults in a Migrant-Sending Community in Central Mexico. Popul. Res. Policy Rev. 2018, 37, 229–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelblute, H.B.; Altman, C.E. Father Absence, Social Networks, and Maternal Ratings of Child Health: Evidence from the 2013 Social Networks and Health Information Survey in Mexico. Matern. Child Health J. 2018, 22, 626–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez-Vazquez, E.; Flippen, C.; Parrado, E. Migration and depression: A cross-national comparison of Mexicans in sending communities and Durham, NC. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 219, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghajanian, A.; Alihoseini, J.; Thompson, V. Husband’s Circular Migration and the Status of Women left behind in Lamerd District, Iran A pilot study. Asian Popul. Stud. 2014, 10, 40–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, E.; Jordan, L.P. Migrant Parents and the Psychological Well-Being of Left-Behind Children in Southeast Asia. J. Marriage Fam. 2011, 73, 763–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abas, M.A.; Punpuing, S.; Jirapramukpitak, T.; Guest, P.; Tangchonlatip, K.; Leese, M.; Prince, M. Rural-urban migration and depression in ageing family members left behind. Br. J. Psychiatry 2009, 195, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abas, M.; Tangchonlatip, K.; Punpuing, S.; Jirapramukpitak, T.; Darawuttimaprakorn, N.; Prince, M.; Flach, C. Migration of Children and Impact on Depression in Older Parents in Rural Thailand, Southeast Asia. JAMA Psychiatry 2013, 70, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adhikari, R.; Jampaklay, A.; Chamratrithirong, A. Impact of children’s migration on health and health care-seeking behavior of elderly left behind. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, R.; Jampaklay, A.; Chamratrithirong, A.; Richter, K.; Pattaravanich, U.; Vapattanawong, P. The Impact of Parental Migration on the Mental Health of Children Left Behind. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2014, 16, 781–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciborowski, H.M.; Hurst, S.; Perez, R.L.; Swanson, K.; Leas, E.; Brouwer, K.C.; Shakya, H.B. Through our own eyes and voices: The experiences of those “left-behind” in rural, indigenous migrant-sending communities in western Guatemala. J. Migr. Health 2022, 5, 100096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczan, D.J.; Orgill-Meyer, J. The impact of climate change on migration: A synthesis of recent empirical insights. Clim. Change 2020, 158, 281–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellanos, E.J.; Thomas, T.S.; Dunston, S. Climate Change, Agriculture, and Adaptation Options for Guatemala; International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Goldscheider, C. Migration and Social Structure: Analytic Issues and Comparative Perspectives in Developing Nations. Sociol. Forum 1987, 2, 674–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, J.M.; Casey, J.A. The centrality of social ties to climate migration and mental health. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidbrink, L. Circulation of care among unaccompanied migrant youth from Guatemala. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2018, 92, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolin, C. Transnational Ruptures: Gender and Forced Migration; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkerson, J.A.; Yamawaki, N.; Downs, S.D. Effects of Husbands’ Migration on Mental Health and Gender Role Ideology of Rural Mexican Women. Health Care Women Int. 2009, 30, 614–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, H.R. The emotional toll of out-migration on mothers and fathers left behind in Mexico. Int. Migr. 2017, 55, 156–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelblute, H.B.; Clark, S.; Mann, L.; McKenney, K.M.; Bischof, J.J.; Kistler, C. Promotoras Across the Border: A Pilot Study Addressing Depression in Mexican Women Impacted by Migration. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2014, 16, 492–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bever, S.W. Migration and the transformation of gender roles and hierarchies in Yucatan. Urban. Anthropol. Stud. Cult. Syst. World Econ. Dev. 2002, 31, 199–230. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, M.J.; Moran-Taylor, M.J.; Ruiz, D.R. Land, Ethnic, and Gender Change: Transnational Migration and its effects on Guatemalan Lives and Landscapes. Geoforum 2006, 37, 41–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, R.L. Crossing the border from boyhood to manhood: Male youth experiences of crossing, loss, and structural violence as unaccompanied minors. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2014, 19, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Johnson, R.L.; Woodhouse, M. Securing the return: How enhanced US border enforcement fuels cycles of debt migration. Antipode 2018, 50, 976–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, L. No safe space: Neoliberalism and the production of violence in the lives of Central American migrants. J. Race Ethn. Politics 2020, 5, 4–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dudley, S.S. Drug Trafficking Organizations in Central America: Transportistas, Mexican Cartels and Maras; Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, Mexico Institute: Mexico City, Mexico, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Foxen, P. In Search of Providence: Transnational Mayan Identities; Vanderbilt University Press: Nashville, TN, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Carte, L.; Radel, C.; Schmook, B. Subsistence migration: Smallholder food security and the maintenance of agriculture through mobility in Nicaragua. Geogr. J. 2019, 185, 180–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spalding, R.J. The politics of implementation: Social movements and mining policy implementation in Guatemala. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2023, 13, 101216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batz, G. Ixil Maya resistance against megaprojects in Cotzal, Guatemala. Theory Event 2020, 23, 1016–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galemba, R.B. ‘He used to be a Pollero’the securitisation of migration and the smuggler/migrant nexus at the Mexico-Guatemala border. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2018, 44, 870–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İnalcı, A. Analyzing Securitization of Migration During the Pandemic: Examples From the United States. J. Int. Relat. Polit. Sci. Stud. 2021, 1, 5–21. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchıson, H. Continuity and change: Comparing the securitization of migration under the Obama and Trump administrations. Percept. J. Int. Aff. 2020, 25, 81–98. [Google Scholar]

- Massey, D.S.; Goldring, L.; Durand, J. Continuities in Transnational Migration: An Analysis of Nineteen Mexican Communities. Am. J. Sociol. 1994, 99, 1492–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandervoort, D.J.; Skorikov, V.B. Physical health and social network characteristics as determinants of mental health across cultures. Curr. Psychol. 2002, 21, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisal, C.M.; Turnip, S.S. Predictors of loneliness among the left-behind children of migrant workers in Indonesia. J. Public Ment. Health 2019, 18, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasserman, S.; Faust, K. Social Network Analysis: Methods and Applications; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, J.; Carrington, P.J. The SAGE Handbook of Social Network Analysis; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, L.C. Centrality in social networks conceptual clarification. Soc. Netw. 1978, 1, 215–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenquist, J.N.; Fowler, J.H.; Christakis, N.A. Social network determinants of depression. Mol. Psychiatry 2011, 16, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreager, D.A.; Rulison, K.; Moody, J. Delinquency and the structure of adolescent peer groups. Criminology 2011, 49, 95–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, M. The Strength of Weak Ties: A Network Theory Revisited. Social Structure and Network Analysis; Marsden, P.V., Lin, N., Eds.; Sage: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Valente, T.W. Social Networks and Health: Models, Methods, and Applications; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Trotter, R.T.; Baldwin, J.A.; Bowen, A. Network structure and proxy network measures of HIV, drug and incarceration risks for active drug users. Connections 1995, 18, 89–104. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, X.; Adamic, L.A.; Strauss, M.J. Networks of strong ties. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Appl. 2007, 378, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domènech-Abella, J.; Lara, E.; Rubio-Valera, M.; Olaya, B.; Moneta, M.V.; Rico-Uribe, L.A.; Ayuso-Mateos, J.L.; Mundó, J.; Haro, J.M. Loneliness and depression in the elderly: The role of social network. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2017, 52, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bearman, P.S.; Moody, J. Suicide and friendships among American adolescents. Am. J. Public Health 2004, 94, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, J.; Eagle, D.E. Social Networks, Support, and Depressive Symptoms: Gender Differences among Clergy. Socius 2019, 5, 2378023119873821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, R.M.; Carte, L. Migration and development? The gendered costs of migration on Mexico’s rural “left behind”. Geogr. Rev. 2016, 106, 399–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Mental Health Atlas. 2020. Available online: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/mental-health/mental-health-atlas-2020-country-profiles/gtm.pdf?sfvrsn=f3c87a9_5 (accessed on 31 December 2021).

- Naber, J.; Mactaggart, I.; Dionicio, C.; Polack, S. Anxiety and depression in Guatemala: Sociodemographic characteristics and service access. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0272780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabin, M.; Sabin, K.; Kim, H.; Vergara, M.; Varese, L. The Mental Health Status of Mayan Refugees after Repatriation to Guatemala. Rev. Panam. Salud Pública 2006, 19, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, A.; Joscelyne, A.; Granski, M.; Rosenfeld, B. Pre-Migration Trauma Exposure and Mental Health Functioning among Central American Migrants Arriving at the US Border. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0168692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puac-Polanco, V.D.; Lopez-Soto, V.A.; Kohn, R.; Xie, D.; Richmond, T.S.; Branas, C.C. Previous violent events and mental health outcomes in Guatemala. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, 764–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branas, C.C.; Dinardo, A.R.; Puac Polanco, V.D.; Harvey, M.J.; Vassy, J.L.; Bream, K. An exploration of violence, mental health and substance abuse in post-conflict Guatemala. Health 2013, 5, 825–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pribilsky, J. Nervios andModern Childhood’ Migration and Shifting Contexts of Child Life in the Ecuadorian Andes. Childhood 2001, 8, 251–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran-Taylor, M.J. When mothers and fathers migrate north: Caretakers, children, and child rearing in Guatemala. Lat. Am. Perspect. 2008, 35, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Ares, R.; Lykes, M.B. Mayan young women and photovoice: Exposing state violence(s) and gendered migration in rural Guatemala. Community Psychol. Glob. Perspect. 2016, 2, 56. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn, L.M.; de Cabrera, G. Left Alone, the Widows of the War: Trauma Reframed through Community Empowerment in Guatemala. In Feminist Conversations: Women, Trauma and Empowerment in Post-Transitional Societies; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2009; p. 91. [Google Scholar]

- Oglesby, E.; Ross, A. Guatemala’s Genocide Determination and the Spatial Politics of Justice. Space Polity 2009, 13, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lykes, M.; Tavara, G.; Sibley, E.; Ferreira van Leer, K. Maya k’iche’ families and intergenerational migration within and across borders: An exploratory mixed-methods study 1. Community Psychol. Glob. Perspect. 2020, 6, 52–73. [Google Scholar]

- Brabeck, K.M.; Lykes, M.B.; Hershberg, R. Framing immigration to and deportation from the United States: Guatemalan and Salvadoran families make meaning of their experiences. Community Work Fam. 2011, 14, 275–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hershberg, R.M.; Lykes, M.B. Redefining Family: Transnational Girls Narrate Experiences of Parental Migration, Detention, and Deportation. Forum Qual. Sozialforschung Forum: Qual. Soc. Res. 2012, 14, 1770. [Google Scholar]

- Comisión para el Esclarecimiento Histórico. Guatemala: Memoria del Silencio; CEH: Guatemala City, Guatemala, 1999.

- Dill, K. International human rights and local justice in Guatemala: The Rio Negro (Pak’oxom) and Agua Fria trials. Cult. Dyn. 2005, 17, 323–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartrop, P.R. Modern Genocide: A Documentary and Reference Guide; Bloomsbury Publishing USA: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 100–106. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S.; Wills, T.A. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 1985, 98, 310–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkley, L.C.; Browne, M.W.; Cacioppo, J.T. How can I connect with thee? Let me count the ways. Psychol. Sci. 2005, 16, 798–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Wang, X.; Zhang, M.; Tong, D.; Li, J.; Xu, T.; Qiu, J.; Wei, D. Understanding the dual role of individual position in multidimensional social support networks and depression levels: Insights from a nomination-driven framework. Soc. Sci. Med. 2025, 373, 117968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, A. Are respondents more likely to list alters with certain characteristics?: Implications for name generator data. Soc. Netw. 2004, 26, 289–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radloff, L.S. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1977, 1, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amtmann, D.; Kim, J.; Chung, H.; Bamer, A.M.; Askew, R.L.; Wu, S.; Cook, K.F.; Johnson, K.L. Comparing CESD-10, PHQ-9, and PROMIS depression instruments in individuals with multiple sclerosis. Rehabil. Psychol. 2014, 59, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shean, G.; Baldwin, G. Sensitivity and specificity of depression questionnaires in a college-age sample. J. Genet. Psychol. 2008, 169, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissman, M.M.; Sholomskas, D.; Pottenger, M.; Prusoff, B.A.; Locke, B.Z. Assessing depressive symptoms in five psychiatric populations: A validation study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1977, 106, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilagut, G.; Forero, C.G.; Barbaglia, G.; Alonso, J. Screening for depression in the general population with the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D): A systematic review with meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0155431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Grosso, P.; Loret de Mola, C.; Vega-Dienstmaier, J.M.; Arevalo, J.M.; Chavez, K.; Vilela, A.; Lazo, M.; Huapaya, J. Validation of the spanish center for epidemiological studies depression and zung self-rating depression scales: A comparative validation study. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e45413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.H.; Grajeda, R.; Melgar, P.; Marcinkevage, J.; DiGirolamo, A.M.; Flores, R.; Martorel, R. Micronutrient supplementation may reduce symptoms of depression in Guatemalan women. Arch. Latinoam. Nutr. 2009, 59, 278–286. [Google Scholar]

- Franco-Díaz, K.L.; Fernández-Niño, J.A.; Astudillo-García, C.I. Prevalence of depressive symptoms and factorial invariance of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies (CES-D) Depression Scale in a group of Mexican indigenous population. Biomedica 2018, 38, 127–140. [Google Scholar]

- Grzywacz, J.; Alterman, T.; Muntaner, C.; Shen, R.; Li, J.; Gabbard, S.; Nakamoto, J.; Carroll, D. Mental health research with Latino farmworkers: A systematic evaluation of the short CES-D. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2010, 12, 652–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prescott, C.A.; McArdle, J.J.; Hishinuma, E.S.; Johnson, R.C.; Miyamoto, R.H.; Andrade, N.N.; Edman, J.L.; Makini, G.K.; Nahulu, L.B.; Yuen, N.Y.C.; et al. Prediction of Major Depression and Dysthymia From CES-D Scores Among Ethnic Minority Adolescents. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1998, 37, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapleski, E.E.; Lamphere, J.K.; Kaczynski, R.; Lichtenberg, P.A.; Dwyer, J.W. Structure of a depression measure among American Indian elders: Confirmatory factor analysis of the CES-D scale. Res. Aging 1997, 19, 462–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manson, S.M.; Ackerson, L.M.; Dick, R.W.; Baron, A.E.; Fleming, C.M. Depressive symptoms among American Indian adolescents: Psychometric characteristics of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). Psychol. Assess. A J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1990, 2, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perreira, K.M.; Deeb-Sossa, N.; Harris, K.M.; Bollen, K. What are we measuring? An evaluation of the CES-D across race/ethnicity and immigrant generation. Soc. Forces 2005, 83, 1567–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dick, R.W.; Beals, J.; Keane, E.M.; Manson, S.M. Factorial structure of the CES-D among American Indian adolescents. J. Adolesc. 1994, 17, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harry, M.L.; Crea, T.M. Examining the measurement invariance of a modified CES-D for American Indian and non-Hispanic White adolescents and young adults. Psychol. Assess. 2018, 30, 1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Getnet, B.; Alem, A. Validity of the center for epidemiologic studies depression scale (CES-D) in Eritrean refugees living in Ethiopia. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e026129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, R.E.; Rhoades, H.M.; Vernon, S.W. Using the CES-D scale to screen for depression and anxiety: Effects of language and ethnic status. Psychiatry Res. 1990, 31, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacasse, J.J.; Forgeard, M.J.; Jayawickreme, N.; Jayawickreme, E. The factor structure of the CES-D in a sample of Rwandan genocide survivors. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2014, 49, 459–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somervell, P.D.; Beals, J.; Kinzie, J.D.; Boehnlein, J.; Leung, P.; Manson, S.M. Use of the CES-D in an American Indian village. Cult. Med. Psychiatry 1992, 16, 503–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Available online: https://sites.cscc.unc.edu/hchs/ (accessed on 4 June 2018).

- Ray, G.T.; Mertens, J.R.; Weisner, C. Family members of people with alcohol or drug dependence: Health problems and medical cost compared to family members of people with diabetes and asthma. Addiction 2009, 104, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, N.; Sharma, S.; Ghai, S.; Basu, D.; Kumari, D.; Singh, D.; Kaur, G. Living with an alcoholic partner: Problems faced and coping strategies used by wives of alcoholic clients. Ind. Psychiatry J. 2016, 25, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anda, R.F.; Whitfield, C.L.; Felitti, V.J.; Chapman, D.; Edwards, V.J.; Dube, S.R.; Williamson, D.F. Adverse childhood experiences, alcoholic parents, and later risk of alcoholism and depression. Psychiatr. Serv. 2002, 53, 1001–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Leij, M.; Goyal, S. Strong ties in a small world. Rev. Netw. Econ. 2011, 10, 1446–9022.1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Johnston, R.; Jones, K.; Manley, D. Confounding and collinearity in regression analysis: A cautionary tale and an alternative procedure, illustrated by studies of British voting behaviour. Qual. Quant. 2018, 52, 1957–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfield, S.; Vertefuille, J.; McAlpine, D.D. Gender Stratification and Mental Health: An Exploration of Dimensions of the Self. Soc. Psychol. Q. 2000, 63, 208–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C.; Berglund, P.; Demler, O.; Jin, R.; Merikangas, K.R.; Walters, E.E. Lifetime Prevalence and Age-of-Onset Distributions of DSM-IV Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2005, 62, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. The Culture of Migration in Rural Oaxaca; Austin University Texas: Austin, TX, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, T.D. The culture of Mexican migration. Crit. Anthropol. 2010, 30, 399–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Song, Q. From the culture of migration to the culture of remittances: Evidence from immigrant-sending communities in China. Chin. Sociol. Rev. 2018, 50, 163–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Baya, D.; López-Gaviño, F.; Ibáñez-Alfonso, J.A. Mental health, quality of life and violence exposure in low-socioeconomic status children and adolescents of Guatemala. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7620. [Google Scholar]

- Pan American Health Organization. Prevalence of Depression. 2015. Available online: https://www.paho.org/en/noncommunicable-diseases-and-mental-health/noncommunicable-diseases-and-mental-health-data-portal-1 (accessed on 31 December 2021).

- Kessler, R.C.; Bromet, E.J. The epidemiology of depression across cultures. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2013, 34, 119–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chamarbagwala, R.; Morán, H. The human capital consequences of civil war: Evidence from Guatemala. J. Dev. Econ. 2011, 94, 41–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carling, J.; Collins, F. Aspiration, Desire and Drivers of Migration; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2018; Volume 44, pp. 909–926. [Google Scholar]

- De Haas, H. A theory of migration: The aspirations-capabilities framework. Comp. Migr. Stud. 2021, 9, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secor, S.P.; Limke-McLean, A.; Wright, R.W. Whose support matters? Support of friends (but Not Family) may predict affect and wellbeing of adults faced with negative life events. J. Relatsh. Res. 2017, 8, e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Leary, M.R. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol. Bull. 1995, 117, 497–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, W.A.; Kolody, B.; Valle, R.; Weir, J. Social Networks, Social Support, and their Relationship to Depression among Immigrant Mexican Women. Hum. Organ. 1991, 50, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.-M. Migrant Networks and International Migration: Testing Weak Ties. Demography 2013, 50, 1243–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, R.L.; Lorenz, F.O.; Wu, C.-i.; Conger, R.D. Social network and marital support as mediators and moderators of the impact of stress and depression on parental behavior. Dev. Psychol. 1993, 29, 368–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaspersen, M.; Matthiesen, S.B.; Götestam, K.G. Social network as a moderator in the relation between trauma exposure and trauma reaction: A survey among UN soldiers and relief workers. Scand. J. Psychol. 2003, 44, 415–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Gou, Z.; Zuo, J. Social support mediates loneliness and depression in elderly people. J. Health Psychol. 2016, 21, 750–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, J.H.; Christakis, N.A. Dynamic spread of happiness in a large social network: Longitudinal analysis over 20 years in the Framingham Heart Study. Br. Med. J. 2008, 337, a2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, J.; Johnson, C.A.; Leventhal, A.; Milam, J.; Pentz, M.A.; Schwartz, D.; Valente, T.W. Social network status and depression among adolescents: An examination of social network influences and depressive symptoms in a Chinese sample. Res. Hum. Dev. 2011, 8, 67–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, R.S. A note on strangers, friends and happiness. Soc. Netw. 1987, 9, 311–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacioppo, J.T.; Fowler, J.H.; Christakis, N.A. Alone in the crowd: The structure and spread of loneliness in a large social network. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 97, 977–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, L.K.; Blazer, D.G.; Hughes, D.C.; Fowler, N. Social support and the outcome of major depression. Br. J. Psychiatry 1989, 154, 478–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plasencia, M.Z. “I Don’t Have Much Money, but I Have a Lot of Friends”: How Poor Older Latinxs Find Social Support in Peer Friendship Networks. Soc. Probl. 2023, 70, 755–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yucel, D.; Latshaw, B.A. Mental health across the life course for men and women in married, cohabiting, and living apart together relationships. J. Fam. Issues 2023, 44, 2025–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, P.R. Why is depression more prevalent in women? J. Psychiatry Neurosci. JPN 2015, 40, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brommelhoff, J.A.; Conway, K.; Merikangas, K.; Levy, B.R. Higher rates of depression in women: Role of gender bias within the family. J. Women’s Health 2004, 13, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paykel, E.S. Depression in women. Br. J. Psychiatry 1991, 158, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawachi, I.; Berkman, L.F. Social ties and mental health. J. Urban. Health 2001, 78, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Luo, S.; Liu, X. Development of Social Support Networks by Patients With Depression Through Online Health Communities: Social Network Analysis. JMIR Med. Inform. 2021, 9, e24618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Chen, F. Evolving parent-adult child relations: Location of multiple children and psychological well-being of older adults in China. Public Health 2018, 158, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiuru, N.; Burk, W.J.; Laursen, B.; Nurmi, J.-E.; Salmela-Aro, K. Is depression contagious? A test of alternative peer socialization mechanisms of depressive symptoms in adolescent peer networks. J. Adolesc. Health 2012, 50, 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McPherson, M.; Smith-Lovin, L.; Cook, J.M. Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2001, 27, 415–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, D.R.; Kornienko, O.; Fox, A.M. Misery does not love company: Network selection mechanisms and depression homophily. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2011, 76, 764–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zalk, M.H.W.; Kerr, M.; Branje, S.J.; Stattin, H.; Meeus, W.H. It takes three: Selection, influence, and de-selection processes of depression in adolescent friendship networks. Dev. Psychol. 2010, 46, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prinstein, M.J. Moderators of peer contagion: A longitudinal examination of depression socialization between adolescents and their best friends. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2007, 36, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howes, M.J.; Hokanson, J.E.; Loewenstein, D.A. Induction of depressive affect after prolonged exposure to a mildly depressed individual. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1985, 49, 1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, W.; Kamo, Y. Contextualizing depressive contagion: A multilevel network approach. Soc. Ment. Health 2016, 6, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Robinson, D.T.; Wu, C.-I. Isolation but Diffusion? A Structural Account of Depression Clustering among Adolescents. Soc. Psychol. Q. 2020, 83, 363–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarris, K.E. Casi Como Madres: Examining the Role of Grandmothers in Global Care Chains; UCLA: Center for the Study of Women: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Dávalos, C. Localizing masculinities in the global care chains: Experiences of migrant men in Spain and Ecuador. Gend. Place Cult. 2020, 27, 1703–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mean (SD) Age in years 33.96 (16.51) | |||

| Mean (SD) CES-D depression score 12.38 (9.90) | |||

| Total network density 0.00855 | |||

| Proportion of Total Sample | Proportion with CESD Score Above 16 (p-Value) | Proportion with Emigrant Tie (p-Value) | |

| CES-D score above 16 | |||

| No | 67% | - | 52% (0.093) |

| Yes | 33% | - | 59% |

| Emigrant in the United States | |||

| No | 46% | 29% (0.093) | - |

| Yes | 54% | 36% | - |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 59% | 45% (<0.001) | 53% (0.166) |

| Male | 41% | 16% | 57% |

| Marital status | |||

| Single | 36% | 19% (0.838) | 55% (1.00) |

| Married/civil union | 64% | 33% | 54% |

| Education | |||

| None | 39% | 46% (<0.001) | 50% (0.003) |

| Primary school | 53% | 23% | 54% |

| More than primary | 8% | 30% | 76% |

| Religious affiliation | |||

| No | 42% | 28% (0.44) | 52% (0.307) |

| Yes | 58% | 36% | 56% |

| Income sufficiency | |||

| Sufficient | 27% | 29% (0.313) | 61% (0.055) |

| Not sufficient | 73% | 34% | 52% |

| Self-alcohol dependency | |||

| No | 84% | 31% (0.18) | 53% (0.39) |

| Yes | 16% | 39% | 58% |

| Household alcohol dependency | |||

| No | 63% | 29% (0.016) | 55% (0.727) |

| Yes | 37% | 39% | 53% |

| Beta | SE | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emigrant tie | |||

| No | Ref | ||

| Yes | 0.298 | 0.169 | 0.078 |

| Number of emigrant ties | 0.096 | 0.031 | 0.002 |

| Age in years | 0.013 | 0.005 | <0.001 |

| Age categories | |||

| 15–20 | Ref | ||

| 21–29 | 0.486 | 0.247 | 0.049 |

| 30–43 | 0.927 | 0.238 | <0.001 |

| 44–88 | 0.738 | 0.242 | 0.002 |

| Sex | |||

| Men | Ref | ||

| Women | 1.468 | 0.197 | <0.001 |

| Marital status | |||

| Single | Ref | ||

| Married/civil union | 0.051 | 0.175 | 0.77 |

| Education | |||

| None | Ref | ||

| Primary school | −1.082 | 0.18 | <0.001 |

| More than primary | −0.724 | 0.323 | 0.025 |

| Religious affiliation | |||

| No | Ref | ||

| Yes | 0.361 | 0.172 | 0.036 |

| Income sufficiency | |||

| Sufficient | Ref | ||

| Not sufficient | 0.211 | 0.191 | 0.27 |

| Household alcohol dependency | |||

| No | Ref | ||

| Yes | 0.425 | 0.171 | 0.013 |

| Friend/neighbor emigrated | |||

| No | Ref | ||

| Yes | 0.604 | 0.192 | 0.002 |

| Spouse emigrated | |||

| No | Ref | ||

| Yes | 0.426 | 0.374 | 0.25 |

| Parent emigrated | |||

| No | Ref | ||

| Yes | −0.329 | 0.482 | 0.49 |

| Child emigrated | |||

| No | Ref | ||

| Yes | −0.066 | 0.272 | 0.81 |

| Sibling emigrated | |||

| No | Ref | ||

| Yes | 0.211 | 0.198 | 0.29 |

| Spouse in home network | |||

| No | Ref | ||

| Yes | −0.255 | 0.175 | 0.15 |

| Mother in home network | |||

| No | Ref | ||

| Yes | −0.375 | 0.176 | 0.033 |

| Father in home network | |||

| No | Ref | ||

| Yes | −0.273 | 0.175 | 0.12 |

| Sibling in home network | |||

| No | Ref | ||

| Yes | −0.383 | 0.192 | 0.047 |

| Total degree | 0.033 | 0.012 | 0.006 |

| In-degree | 0.019 | 0.02 | 0.345 |

| Out-degree | 0.067 | 0.02 | <0.001 |

| Transitivity | −2.184 | 0.879 | 0.013 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emigrant Tie Main Effect Adjusted for Total Degree | Emigrant Tie Main Effect with Transitivity Adjusted for Total Degree | Emigrant Tie Main Effect with Out-Degree | |||||||

| Beta | SE | p | Beta | SE | p | Beta | SE | p | |

| Emigrant tie | |||||||||

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Yes | 0.496 | 0.188 | 0.008 | 0.474 | 0.189 | 0.012 | 0.489 | 0.189 | 0.01 |

| Transitivity | −1.891 | 1.001 | 0.05 | ||||||

| Out-degree | 0.044 | 0.021 | 0.039 | ||||||

| Age in years | 0.01 | 0.006 | 0.117 | 0.01 | 0.006 | 0.107 | 0.012 | 0.006 | 0.05 |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Men | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Women | 1.42 | 0.214 | <0.001 | 1.401 | 0.215 | <0.001 | 1.398 | 0.215 | <0.001 |

| Marital status | |||||||||

| Single | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Married/civil union | −0.126 | 0.206 | 0.541 | −0.144 | 0.208 | 0.489 | −0.112 | 0.205 | 0.585 |

| Education | |||||||||

| None | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Primary school | −0.78 | 0.21 | <0.001 | −0.763 | 0.211 | <0.001 | 0.737 | 0.213 | <0.001 |

| More than primary | −0.23 | 0.369 | 0.532 | −0.171 | 0.371 | 0.644 | −0.187 | 0.371 | 0.615 |

| Religious affiliation | |||||||||

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Yes | 0.179 | 0.195 | 0.36 | 0.147 | 0.197 | 0.454 | 0.166 | 0.196 | 0.398 |

| Household alcohol dependency | |||||||||

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Yes | 0.517 | 0.191 | 0.008 | 0.49 | 0.192 | 0.011 | 0.522 | 0.191 | 0.006 |

| Income sufficiency | |||||||||

| Sufficient | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Not sufficient | 0.348 | 0.211 | 0.099 | 0.331 | 0.212 | 0.118 | 0.368 | 0.212 | 0.082 |

| Total degree | 0.02 | 0.014 | 0.145 | 0.019 | 0.014 | 0.166 | |||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number Emigrant Ties Main Effect Adjusted for Total Degree | Number Emigrant Ties Main Effect with Transitivity Adjusted for Total Degree | Number Emigrant Ties Main Effect with Out-Degree | |||||||

| Beta | SE | p | Beta | SE | p | Beta | SE | p | |

| Number Emigrant ties | 0.1 | 0.035 | 0.004 | 0.097 | 0.035 | 0.005 | 0.099 | 0.035 | 0.004 |

| Transitivity | −1.802 | 1.003 | 0.072 | ||||||

| Out-degree | 0.039 | 0.021 | 0.066 | ||||||

| Age in years | 0.01 | 0.006 | 0.11 | 0.011 | 0.006 | 0.097 | 0.012 | 0.006 | 0.055 |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Men | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Women | 1.392 | 0.214 | <0.001 | 1.374 | 0.216 | <0.001 | 1.371 | 0.215 | <0.001 |

| Marital status | |||||||||

| Single | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Married/civil union | −0.102 | 0.207 | 0.622 | −0.12 | 0.209 | 0.565 | −0.094 | 0.206 | 0.649 |

| Education | |||||||||

| None | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Primary school | −0.758 | 0.21 | <0.001 | −0.745 | 0.211 | <0.001 | −0.714 | 0.213 | <0.001 |

| More than primary | −0.222 | 0.373 | 0.551 | −0.164 | 0.375 | 0.661 | −0.173 | 0.375 | 0.644 |

| Religious affiliation | |||||||||

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Yes | 0.156 | 0.196 | 0.428 | 0.126 | 0.197 | 0.524 | 0.14 | 0.197 | 0.476 |

| Household alcohol dependency | |||||||||

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Yes | 0.481 | 0.192 | 0.012 | 0.456 | 0.193 | 0.018 | 0.487 | 0.192 | 0.011 |

| Income sufficiency | |||||||||

| Sufficient | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Not sufficient | 0.428 | 0.217 | 0.048 | 0.41 | 0.218 | 0.059 | 0.45 | 0.218 | 0.039 |

| Total degree | 0.015 | 0.014 | 0.272 | 0.015 | 0.014 | 0.296 | |||

| Beta | SE | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emigrant tie | |||

| No | Ref | ||

| Yes | 0.851 | 0.375 | 0.023 |

| Number of emigrant ties | 0.098 | 0.058 | 0.089 |

| Age in years | −0.005 | 0.01 | 0.62 |

| Marital status | |||

| Single | Ref | ||

| Married/civil union | 0.407 | 0.214 | 0.057 |

| Education | |||

| None | Ref | ||

| Primary school | −1.014 | 0.219 | <0.001 |

| More than primary | −0.253 | 0.452 | 0.576 |

| Religious affiliation | |||

| No | Ref | ||

| Yes | 0.026 | 0.217 | 0.904 |

| Income sufficiency | |||

| Sufficient | Ref | ||

| Not sufficient | 0.54 | 0.441 | 0.221 |

| Household alcohol dependency | |||

| No | Ref | ||

| Yes | 0.446 | 0.212 | 0.035 |

| Friend/neighbor emigrated | |||

| No | Ref | ||

| Yes | 0.486 | 0.241 | 0.044 |

| Spouse emigrated | |||

| No | Ref | ||

| Yes | 0.067 | 0.397 | 0.866 |

| Parent emigrated | |||

| No | Ref | ||

| Yes | 0.173 | 0.614 | 0.956 |

| Child emigrated | |||

| No | Ref | ||

| Yes | 0.173 | 0.346 | 0.617 |

| Sibling emigrated | |||

| No | Ref | ||

| Yes | 0.182 | 0.249 | 0.734 |

| Spouse in home network | |||

| No | Ref | ||

| Yes | −0.862 | 0.34 | 0.011 |

| Mother in home network | |||

| No | Ref | ||

| Yes | 0.313 | 0.349 | 0.37 |

| Father in home network | |||

| No | Ref | ||

| Yes | 0.72 | 0.353 | 0.042 |

| Sibling in home network | |||

| No | Ref | ||

| Yes | −0.076 | 0.396 | 0.849 |

| Total degree | −0.009 | 0.027 | 0.736 |

| In-degree | −0.127 | 0.109 | 0.244 |

| Out-degree | 0.052 | 0.023 | 0.027 |

| Transitivity | −0.805 | 1.448 | 0.588 |

| Beta | SE | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emigrant tie | |||

| No | Ref | ||

| Yes | 0.27 | 0.206 | 0.19 |

| Number of emigrant ties | 0.093 | 0.039 | 0.017 |

| Age in years | 0.03 | 0.007 | <0.001 |

| Marital status | |||

| Single | Ref | ||

| Married/civil union | 0.051 | 0.175 | 0.77 |

| Education | |||

| None | Ref | ||

| Primary school | −1.082 | 0.18 | <0.001 |

| More than primary | −0.724 | 0.323 | 0.025 |

| Religious affiliation | |||

| No | Ref | ||

| Yes | 0.361 | 0.172 | 0.036 |

| Income sufficiency | |||

| Sufficient | Ref | ||

| Not sufficient | 0.264 | 0.228 | 0.254 |

| Household alcohol dependency | |||

| No | Ref | ||

| Yes | 0.425 | 0.171 | 0.013 |

| Friend/neighbor emigrated | |||

| No | Ref | ||

| Yes | 0.604 | 0.192 | 0.002 |

| Spouse emigrated | |||

| No | Ref | ||

| Yes | 0.426 | 0.374 | 0.25 |

| Parent emigrated | |||

| No | Ref | ||

| Yes | −0.329 | 0.482 | 0.49 |

| Child emigrated | |||

| No | Ref | ||

| Yes | −0.066 | 0.272 | 0.81 |

| Sibling emigrated | |||

| No | Ref | ||

| Yes | 0.211 | 0.198 | 0.29 |

| Spouse in home network | |||

| No | Ref | ||

| Yes | 0.275 | 0.206 | 0.181 |

| Mother in home network | |||

| No | Ref | ||

| Yes | −0.566 | 0.208 | 0.006 |

| Father in home network | |||

| No | Ref | ||

| Yes | −0.523 | 0.209 | 0.012 |

| Sibling in home network | |||

| No | Ref | ||

| Yes | −0.319 | 0.222 | 0.152 |

| Total degree | 0.042 | 0.015 | 0.006 |

| In-degree | 0.065 | 0.028 | 0.022 |

| Out-degree | 0.112 | 0.102 | 0.273 |

| Transitivity | −2.698 | 1.123 | 0.016 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number Emigrant Ties Main Effect Adjusted for Total Degree | Number Emigrant Ties Main Effect with Transitivity | Number Emigrant Ties Main Effect with Out-Degree | |||||||

| Beta | SE | p | Beta | SE | p | Beta | SE | p | |

| Number Emigrant ties | 0.107 | 0.043 | 0.013 | 0.105 | 0.043 | 0.015 | 0.106 | 0.043 | 0.013 |

| Age in years | 0.02 | 0.008 | 0.014 | 0.023 | 0.008 | 0.006 | 0.023 | 0.008 | 0.005 |

| Marital status | |||||||||

| Single | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Married/civil union | 0.114 | 0.239 | 0.635 | 0.149 | 0.241 | 0.536 | 0.137 | 0.239 | 0.567 |

| Education | |||||||||

| None | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Primary school | −0.662 | 0.256 | 0.01 | −0.718 | 0.254 | 0.005 | −0.619 | 0.259 | 0.017 |

| More than primary | 0.15 | 0.496 | 0.762 | 0.269 | 0.509 | 0.598 | 0.183 | 0.499 | 0.714 |

| Religious affiliation | |||||||||

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Yes | 0.043 | 0.238 | 0.855 | 0.018 | 0.239 | 0.939 | 0.02 | 0.239 | 0.932 |

| Household alcohol dependency | |||||||||

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Yes | 0.521 | 0.231 | 0.024 | 0.448 | 0.233 | 0.055 | 0.525 | 0.232 | 0.023 |

| Income sufficiency | |||||||||

| Sufficient | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Not sufficient | 0.37 | 0.253 | 0.146 | 0.309 | 0.255 | 0.225 | 0.386 | 0.254 | 0.129 |

| Transitivity | −2.735 | 1.274 | 0.032 | ||||||

| Out-degree | 0.051 | 0.025 | 0.04 | ||||||

| Total degree | 0.028 | 0.016 | 0.09 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ciborowski, H.M.; Brouwer, K.C.; Hurst, S.; Perez, R.L.; Swanson, K.; Baker, H. Social Network Impacts and Moderators of Depression Among Indigenous Maya People Remaining in Place of Origin in the Migrant-Sending Guatemalan Western Highlands. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1328. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091328

Ciborowski HM, Brouwer KC, Hurst S, Perez RL, Swanson K, Baker H. Social Network Impacts and Moderators of Depression Among Indigenous Maya People Remaining in Place of Origin in the Migrant-Sending Guatemalan Western Highlands. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(9):1328. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091328

Chicago/Turabian StyleCiborowski, Haley M., Kimberly C. Brouwer, Samantha Hurst, Ramona L. Perez, Kate Swanson, and Holly Baker. 2025. "Social Network Impacts and Moderators of Depression Among Indigenous Maya People Remaining in Place of Origin in the Migrant-Sending Guatemalan Western Highlands" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 9: 1328. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091328

APA StyleCiborowski, H. M., Brouwer, K. C., Hurst, S., Perez, R. L., Swanson, K., & Baker, H. (2025). Social Network Impacts and Moderators of Depression Among Indigenous Maya People Remaining in Place of Origin in the Migrant-Sending Guatemalan Western Highlands. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(9), 1328. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091328