The Influence of Therapist Adherence on Multisystemic Therapy Treatment Outcome for Adolescents with Antisocial Behaviours: A Retrospective Study in Western Australian Families

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Child Behaviour Checklist (CBCL/6-18)

2.2.2. Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21)

2.2.3. Parenting Styles and Dimensions Questionnaire (PSDQ)

2.2.4. Parental Monitoring Scale (PM)

2.2.5. Therapist Adherence Measure (TAM-R)

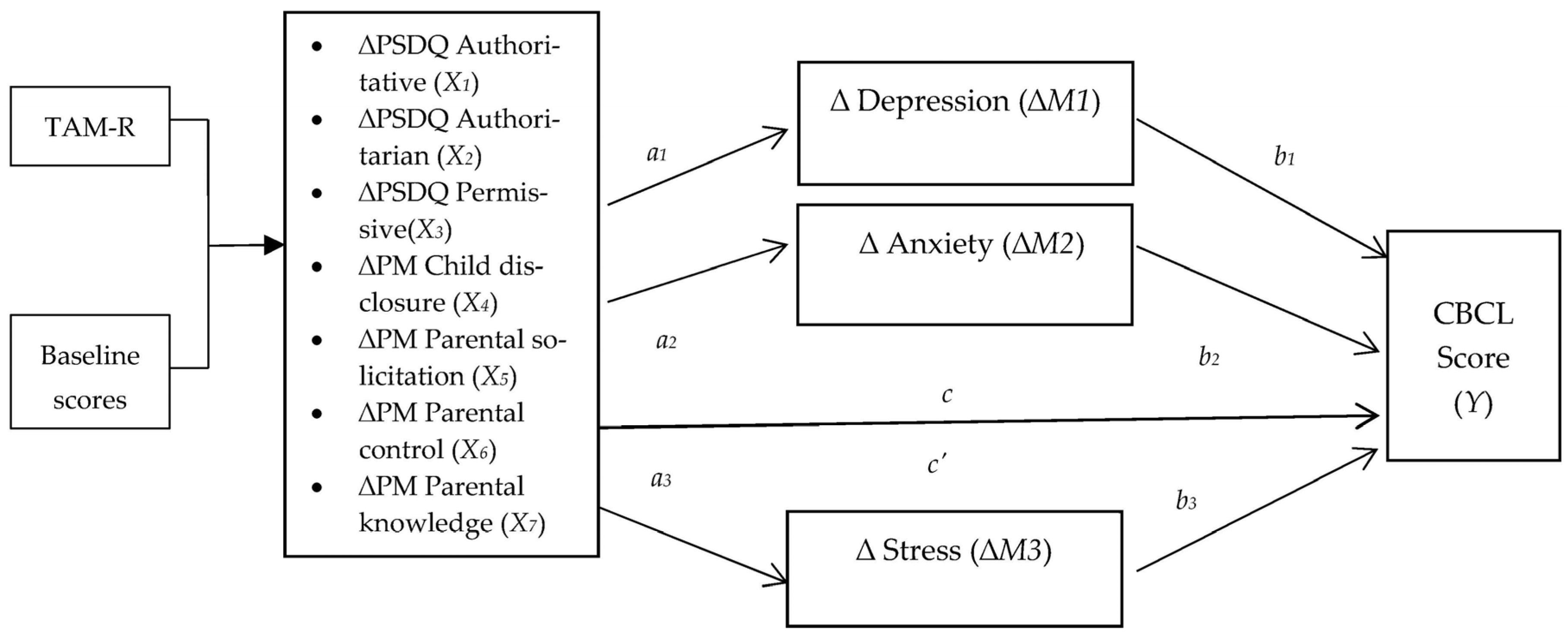

2.3. Data Analytic Strategy

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

3.2. Predictors of Changes in Parental and Adolescent Outcomes

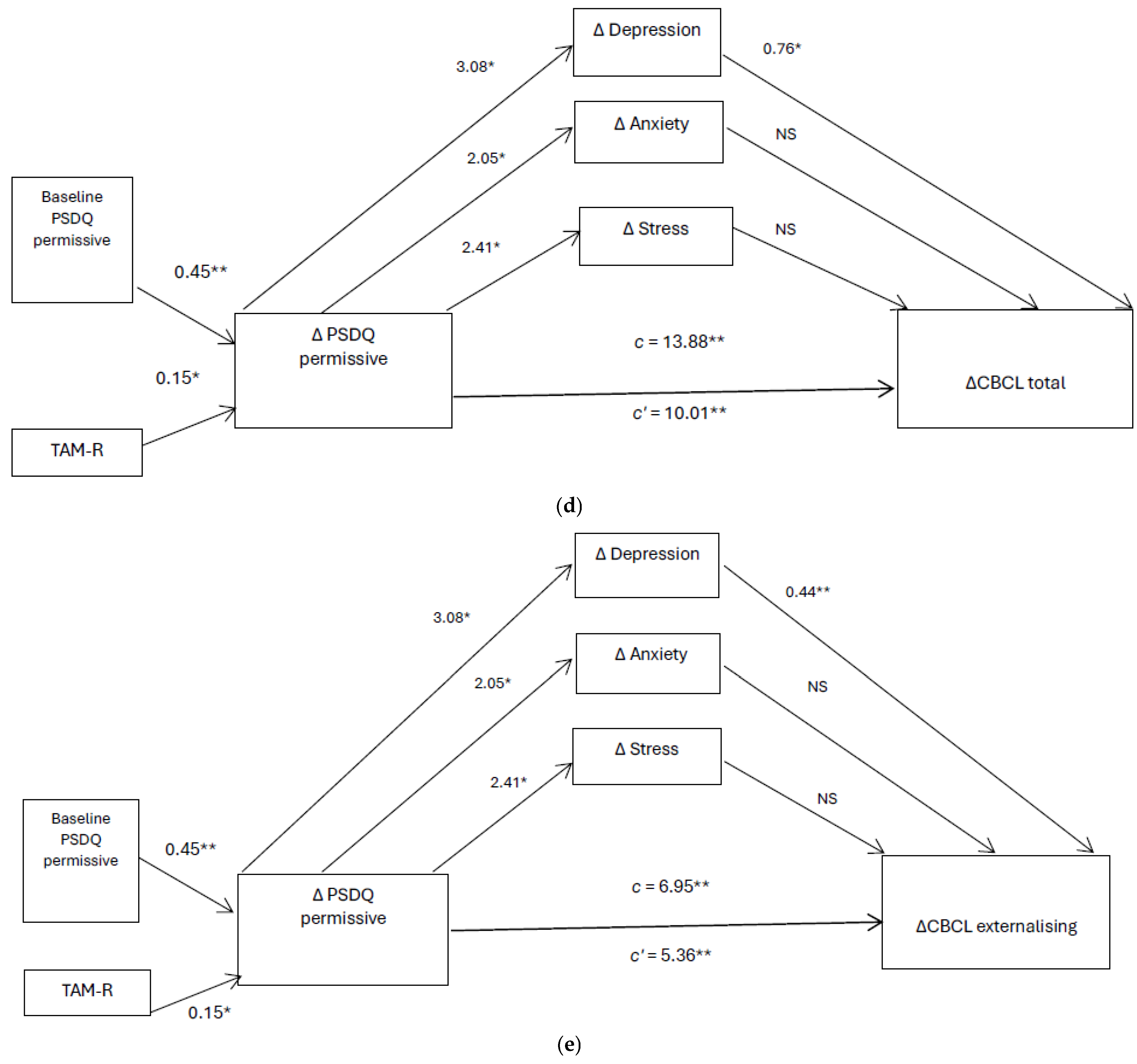

3.3. Path Analysis and Mediating Effect Findings

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Antisocial behaviour and conduct disorders in children and young people: Recognition, intervention and management. In NICE Clinical Guideline 158; National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Social Care Institue for Excellence: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). Australian Burden of Disease Study: Impact and Causes of Illness and Death in Australia 2015; AIHW: Canberra, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, D.; Johnson, S.; Hafekost, J.; Boterhoven De Hann, K.; Sawyer, M.; Ainley, J.; Zubrick, S.R. The Mental Health of Children and Adolescents: Report on the Second Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing; Department of Health: Canberra, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fryers, T.; Brugha, T. Childhood determinants of adult psychiatric disorder. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health 2013, 9, 1–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luby, J.; Belden, A.; Botteron, K.; Marrus, N.; Harms, M.P.; Babb, C.; Nishino, T.; Barch, D. The effects of poverty on childhood brain development: The mediating effect of caregiving and stressful life events. J. Am. Med. Assoc. Pediatr. 2013, 167, 1135–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshikawa, H.; Aber, J.l.; Beardslee, W.R. The effects of poverty on the mental health, and behavioural health of children and youth: Implications for prevention. Am. Psychol. 2012, 67, 272–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, G.; Neary, M.; Polek, E.; Flouri, E. The association between paternal and adolescent depressive symptoms: Evidence from two population-based cohorts. Lancet Psychiatry 2017, 4, 920–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patterson, G.; Forgatch, M. Predicting future clinical adjustment from treatment outcome and process variables. Psychol. Assess. 1995, 7, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, C. Parental Mental Health and Parenting: How are They Related? Emerging Minds. 2020. Available online: https://emergingminds.com.au/resources/parental-mental-health-and-parenting-how-are-they-related/ (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Millward, C.; Matthews, J.; Wade, C.; Forbes, F.; Seward, A. Parent Mental Health (Research Brief); Parenting Research Centre: Melbourne, Australia, 2018; Available online: https://www.parentingrc.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Mental-Health-Research-Brief-Oct-2018.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2022).

- Reupert, A.E.; Maybery, D.J.; Kowalenko, N.M. Children whose parents have a mental illness: Prevalence, need and treatment. Med. J. Aust. 2013, 199, 7–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidov, M.; Grusec, J.E. Untangling the links of parental responsiveness to distress and warmth to child outcomes. Child Dev. 2006, 77, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershoff, E.T.; Grogan-Kaylor, A. Spanking and child outcomes: Old controversies and new meta-analyses. J. Fam. Psychol. 2016, 30, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubrick, S.R.; Smith, G.J.; Nicholson, J.M.; Sanson, A.V.; Jackiewicz, T.A. Parenting and Families in Australia. In FaHCSIA Social Policy Research Paper; Department of Family, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs, Australian Government: Canberra, Australia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Porzig-Drummond, R. Help, not punishment’: Moving on from physical punishment of children. Child. Aust. 2015, 40, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler, S.W.; Borduin, C.M. Family Therapy and Beyond: A Multisystemic Approach to Treating the Behaviour Problems of Children and Adolescents; Brooks/Cole: Pacific Grove, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Minuchin, S. Families and Family Therapy; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Davis-Kean, P.E. The influence of parent education and family income on child achievement: The indirect role of parental expectations and the home environment. J. Fam. Psychol. 2005, 19, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repetti, R.L.; Taylor, S.E.; Seeman, T.E. Risky families: Family social enviornments and the mental and physical health of offspring. Psychol. Bull. 2002, 128, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia’s Children; Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: Canberra, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler, S.W.; Schoenwald, S.K.; Borduin, C.M.; Rowland, M.D.; Cunningham, P.B. Multisystemic Treatment of Antisocial Behaviour in Children and Adolescents; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, M.; Weiss, B.; Han, S.; Gallop, R. The influence of parental factors on therapist adherence in Multi-systemic Therapy. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2010, 36, 857–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Schoenwald, S.K.; Chapman, J.E.; Sheidow, A.J.; Carter, R.E. Long-term youth criminal outcomes in MST transport: The impact of therapist adherence and organisational climate and structure. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2009, 38, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henggeler, S.W.; Melton, G.B.; Brondino, M.J.; Scherer, D.G.; Hanley, J.H. Multisystemic therapy with violent and chronic juvenile offenders and their families: The role of treatment fidelity in successful dissemination. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1997, 65, 821–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timmons-Mitchell, J.; Bender, M.B.; Kishna, M.A.; Mitchell, C.C. An independent effectiveness trial of multisystemic therapy with juvenile justice youth. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychogy 2006, 35, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huey, S.J.; Henggeler, S.W.; Brondino, M.J.; Pickrel, S.G. Mechanisms of change in multisystemic therapy: Reducing delinquent behaviour through therapist adhearance and improved family and peer functioning. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2000, 68, 451–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MST Services. Multisystemic Therapy Research at a Glance: Published MST Outcome, Implementation and Benchmarking Studies. MST Services. 2022. Available online: https://info.mstservices.com/researchataglance (accessed on 3 July 2022).

- Adamson, N.A.; Campbell, E.C.; Kress, V.E. Disruptive, impulse-control, and conduct disorders, and elimination disorders. In Treating Those with Mental Disorders: A Comprehensive Approch to Case Conceptualisation and Treatment, 1st ed.; Kress, V.E., Paylo, M.J., Eds.; Pearson: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 384–420. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach, T.M.; Rescorla, L.A. Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms & Profiles; University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families: Burlington, VT, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Lovibond, S.H.; Lovibond, P.F. Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales; Psychology Foundation Monograph: Sydney, Australia, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, C.; Mandleco, B.; Olsen, S.F.; Hart, C.H. The parenting styles and dimensions questionnaire (PSDQ). In Handbook of Family Measurement Techniques; Perlmutter, B.F., Touliatos, J., Holden, G.W., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001; Volume 3, pp. 319–321. [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind, D. Rearing competent children. In Child Development Today and Tomorrow; Damon, W., Ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1989; pp. 349–378. [Google Scholar]

- Stattin, H.; Kerr, M. Parental Monitoring: A reinterpretation. Child Dev. 2000, 71, 1072–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henggeler, S.W.; Borduin, C.M.; Schoenwald, S.K.; Huey, S.J.; Chapman, J.E. Multisystemic Therapy Adherence Scale-Revised (TAM-R); Department of Psychiatry & Behavioural Sciences, Medical University of South Carolina: Charleston, SC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lange, A.M.C.; Van der Rijken, R.E.A.; Delsing, M.J.M.H.; Busschbach, J.J.V.; Scholte, R.H.J. Development of therapist adherence in relation to treatment outcomes of adolescents with behavioral problems. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychogy 2019, 48, S337–S346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approch; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gautam, N.; Rahman, M.M.; Khanam, R. Adverse childhood experiences and externalising, internalising and prosocial behaviours in childrend and adolescents: A longitudinal study. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 363, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, L.M.; Gracey, K.; Shaffer, A.; Ebert, J.; Kuhn, T.; Watson, K.H.; Gruhn, M.; Vreeland, A.; Siciliano, R.; Dickey, L. Comparison of three models of adverse childhood experiences: Association with child and adolescent internalising and externalising symptoms. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2021, 139, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, M.L.; Huey, S.J., Jr.; Cunningham, P. Predictive validity of an observer-rated adherence protocol for multisystemic therapy with juvenile drug offenders. J. Subst. Abus. Treat. 2017, 76, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoenwald, S.K.; Carter, R.E.; Chapman, J.E.; Sheidow, A.J. Therapist adherence and organisational effects on change in youth behaviour problems one year after multisystemic therapy. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2008, 35, 379–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dekovic, M.; Asscher, J.J.; Manders, W.A.; Prins, P.J.M.; Van De Laan, P. Within intervention change: Mediators of intervention effects during multisystemic therapy. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2012, 80, 574–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, L.; Hudson, A.; Matthews, J. Parental monitoring: A process model of parent-adolescent interaction. Behav. Chang. 2003, 20, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, M.; Stattin, H.; Trost, K. To know you is to trust you: Parents’ trust is rooted in child disclosure of information. J. Adolesc. Health 1999, 22, 737–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keijsers, L.; Branje, S.J.T.; Van der Valk, I.E.; Meeus, W. Reciprocal effects between parental solicitation, parental control, adolescent disclosure, and adolescent delinquency. J. Res. Adolesc. 2010, 20, 88–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delforterie, M.J.; Verweij, K.J.H.; Creemers, H.E.; Van Lier, P.A.C.; Koot, H.M.; Branje, S.J.T.; Huizink, A.C. Parental solicitation, parental control, child disclosure, and substance use: Native and immigrant Dutch adolescents. Ethn. Health 2016, 21, 535–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, A.; Loukas, A.; Pasch, K.E. Child disclosure, parental solicitation, and adjustment problems: Parental support as a mediator. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2021, 52, 430–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Loon, L.M.A.; Granic, I.; Engels, R.C.M. The role of maternal depression on treatment outcome for children with externalising behaviour problems. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2011, 33, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckshtain, D.; Marchette, L.K.; Schleider, J.; Weisz, J.R. Parental depressive symptoms as a predictor of outcome in the treatment of child depression. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2018, 46, 825–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadock, B.J.; Sadock, V.A. Kaplan and Sadock’s Synopsis of Psychiatry: Behavioural Sciences/Clinical Psychiatry; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bywater, T.; Hutchings, J.; Daley, D.; Whitaker, C.; Yeo, S.T.; Jones, K.; Eames, C.; Edwards, R.T. Long-term effectiveness of parenting intervention for children at risk of developing conduct disorder. Br. J. Psychiatry 2009, 195, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartwright, N.; Munro, E. The limitations of randomised control trials in predicting effectiveness. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2010, 16, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, F.A. Notes on the use of randomised controlled trials to evaluate complex interventions: Community treatment orders as an illustrative case. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2017, 23, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Paired Differences | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Treatment | Post-Treatment | 95% CI of Mdiff | t (146) | p | Cohen’s d | ||||

| µ | (SD) | µ | (SD) | LL | UL | ||||

| CBCL | |||||||||

| Internalising problems | 25.11 | 10.81 | 17.25 | 10.74 | 6.36 | 9.36 | 10.35 | <0.001 | 0.85 |

| Externalising problems | 40.42 | 10.86 | 26.27 | 13.42 | 12.13 | 16.19 | 13.78 | <0.001 | 1.14 |

| Total problems | 102.60 | 28.46 | 69.63 | 31.89 | 28.37 | 37.57 | 14.16 | <0.001 | 1.17 |

| DASS | |||||||||

| Depression | 15.47 | 10.82 | 8.60 | 8.87 | 5.52 | 8.75 | 7.80 | <0.001 | 0.72 |

| Anxiety | 11.89 | 9.83 | 6.63 | 8.08 | 3.78 | 6.73 | 7.05 | <0.001 | 0.58 |

| Stress | 20.39 | 9.88 | 13.26 | 9.07 | 5.13 | 8.61 | 8.73 | <0.001 | 0.64 |

| Parental Monitoring (PM) | |||||||||

| Child Disclosure (CD) | 10.87 | 4.56 | 13.44 | 5.18 | −3.30 | −1.83 | −6.88 | <0.001 | −0.57 |

| Parental Solicitation (PS) | 16.39 | 3.31 | 17.33 | 3.85 | −1.44 | −0.33 | −3.31 | <0.05 | −0.26 |

| Parental Control (PC) | 19.66 | 4.40 | 20.72 | 3.88 | −1.64 | −0.47 | −6.93 | <0.001 | −0.29 |

| Parental Knowledge (PK) | 27.84 | 6.78 | 30.82 | 6.61 | −3.79 | −2.10 | −7.24 | <0.001 | −0.57 |

| PSDQ | |||||||||

| Authoritarian | 1.93 | 0.48 | 1.56 | 0.40 | 0.30 | 0.43 | 10.96 | <0.001 | 0.90 |

| Permissiveness | 3.02 | 0.81 | 2.30 | 0.81 | 0.60 | 0.84 | 11.70 | <0.001 | 0.97 |

| Authoritative | 3.77 | 0.54 | 4.02 | 0.55 | −0.32 | −0.18 | −7.24 | <0.001 | −0.61 |

| Measure | B | β | t | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL | UL | |||||

| Model 1 DV = ∆CBCL total Baseline CBCL total TAMR | 0.363 46.45 | 0.366 0.219 R2 = 0.183, | 4.85 2.91 R2adjusted = 0.172 | 0.215 14.88 | 0.510 78.02 | <0.001 0.004 |

| Model 2 DV = ∆CBCL external Baseline CBCL external TAMR | 0.389 18.55 | 0.339 0.198 R2 = 0.157, | 4.43 2.59 R2adjusted = 0.145 | 0.216 4.40 | 0.562 32.70 | <0.001 0.011 |

| Model 3 DV = ∆CBCL internal Baseline CBCL internal TAMR | 0.370 13.64 | 0.434 0.197 R2 = 0.226, | 5.92 2.69 R2adjusted = 0.215 | 0.246 3.62 | 0.493 23.65 | <0.001 0.008 |

| Model 4 DV = ∆PM Child Disclosure Baseline PM Child Disclosure TAMR | −0.358 5.28 | −0.363 0.155 R2 = 0.145, | −4.70 2.01 R2adjusted = 0.133 | −0.509 0.099 | −0.208 10.45 | <0.001 0.046 |

| Model 5 DV = ∆PSDQ authoritarian Baseline PSDQ authoritarian TAMR | 0.503 0.591 | 0.590 0.191 R2 = 0.394, | 9.09 2.94 R2adjusted = 0.386 | 0.394 0.194 | 0.612 0.988 | <0.001 0.004 |

| Model 6 DV = ∆PSDQ permissive Baseline PSDQ permissive TAMR | 0.420 0.840 | 0.454 0.148 R2 = 0.227, | 6.20 2.03 R2adjusted = 0.216 | 0.286 0.020 | 0.554 1.66 | <0.001 0.045 |

| Consequent | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 (∆Dep) | M2 (∆Anx) | M3 (∆Str) | Y (∆CBCL Total) | Y (∆CBCL Int) | Y (∆CBCL Ext) | |||||||||||||||||

| Coeff. | SE | P | Coeff. | SE | P | Coeff. | SE | P | Coeff. | SE | P | Coeff. | SE | P | Coeff. | SE | P | |||||

| X1 (∆PM CD) | a1 | 0.530 | 0.191 | 0.006 | a2 | 0.130 | 0.166 | 0.435 | a3 | 0.143 | 0.182 | 0.432 | c′ | 1.796 | 0.435 | <0.001 | 0.424 | 0.157 | 0.008 | 0.893 | 0.192 | <0.001 |

| M1 (∆Dep) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | b1 | 0.551 | 0.294 | 0.063 | 0.084 | 0.106 | 0.429 | 0.345 | 0.130 | 0.008 | |||

| M1 (∆Anx) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | b2 | 0.293 | 0.300 | 0.329 | 0.131 | 0.108 | 0.227 | 0.023 | 0.132 | 0.861 | |||

| M1 (∆Str) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | b3 | 0.686 | 0.319 | 0.033 | 0.206 | 0.115 | 0.075 | 0.219 | 0.141 | 0.122 | |||

| Constant | iM1 | 5.511 | 0.992 | <0.001 | iM2 | 4.925 | 0.860 | <0.001 | iM3 | 6.768 | 0.942 | <0.001 | iY | 18.137 | 2.527 | <0.001 | 4.033 | 0.910 | <0.001 | 7.808 | 1.117 | <0.001 |

| R2 = 0.050 F(1,145) = 7.687, p < 0.05 | R2 = 0.004 F(1,145) = 0.613, p = 0.435 | R2 = 0.004 F(1,145) = 0.622, p = 0.432 | R2 = 0.366 F(4,142) = 20.467, p < 0.001 | R2 = 0.226 F(4,142) = 10.37 p < 0.001 | R2 = 0.364 F(4,142) = 20.298, p < 0.001 | |||||||||||||||||

| X2 (∆Authoritarian) | a1 | 7.754 | 2.079 | <0.001 | a2 | 5.32 | 1.79 | 0.004 | a3 | 6.44 | 1.947 | 0.001 | c′ | 10.62 | 5.08 | 0.039 | 2.427 | 1.791 | 0.177 | 5.104 | 2.280 | 0.027 |

| M1 (∆Dep) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | b1 | 0.793 | 0.298 | 0.009 | 0.141 | 0.105 | 0.180 | 0.468 | 0.133 | <0.001 | |||

| M1 (∆Anx) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | b2 | 0.192 | 0.313 | 0.539 | 0.107 | 0.110 | 0.332 | −0.025 | 140 | 0.858 | |||

| M1 (∆Str) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | b3 | 0.471 | 0.330 | 0.156 | 0.155 | 0.116 | 0.184 | 0.115 | 0.148 | 0.439 | |||

| Constant | iM1 | 3.911 | 1.144 | <0.001 | iM2 | 3.218 | 0.985 | 0.001 | iM3 | 4.666 | 1.071 | <0.001 | iY | 19.070 | 2.834 | <0.001 | 4.277 | 0.998 | <0.001 | 8.322 | 1.269 | <0.001 |

| R2 = 0.088 F(1,144) = 13.904, p < 0.001 | R2 = 0.058 F(1,144) = 8.808, p < 0.05 | R2 = 0.071 F(1,144) = 10.931, p < 0.05 | R2 = 0.304 F(4,141) = 15.429, p < 0.001 | R2 = 0.191 F(4,141) = 8.323, p < 0.001 | R2 = 0.288 F(4,141) = 14.225, p < 0.001 | |||||||||||||||||

| X3 (∆Permissive) | a1 | 3.077 | 1.157 | 0.009 | a2 | 2.049 | 0.990 | 0.040 | a3 | 2.411 | 1.081 | 0.027 | c′ | 10.008 | 2.609 | <0.001 | 1.650 | 0.947 | 0.084 | 5.362 | 1.145 | <0.001 |

| M1 (∆Dep) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | b1 | 0.757 | 0.287 | 0.009 | 0.141 | 0.104 | 0.179 | 0.444 | 0.126 | <0.001 | |||

| M1 (∆Anx) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | b2 | 0.186 | 0.302 | 0.540 | 0.108 | 0.110 | 0.327 | −0.030 | 0.132 | 0.820 | |||

| M1 (∆Str) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | b3 | 0.482 | 0.319 | 0.133 | 0.159 | 0.116 | 0.172 | 0.119 | 0.140 | 0.397 | |||

| Constant | iM1 | 4.547 | 1.206 | <0.001 | iM2 | 3.698 | 1.031 | <0.001 | iM3 | 5.298 | 1.126 | <0.001 | iY | 15.934 | 2.852 | <0.001 | 3.950 | 1.035 | <0.001 | 6.475 | 1.251 | <0.001 |

| R2 = 0.047 F(1,144) = 7.070, p < 0.05 | R2 = 0.029 F(1,144) = 4.284, p < 0.05 | R2 = 0.033 F(1,144) = 4.974, p < 0.05 | R2 = 0.351 F(4,141) = 19.036, p < 0.001 | R2 = 0.198 F(4,141) = 8.689, p < 0.00 | R2 = 0.362 F(4,141) = 19.955, p < 0.001 | |||||||||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nuntavisit, L.; Porter, M.R. The Influence of Therapist Adherence on Multisystemic Therapy Treatment Outcome for Adolescents with Antisocial Behaviours: A Retrospective Study in Western Australian Families. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1310. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081310

Nuntavisit L, Porter MR. The Influence of Therapist Adherence on Multisystemic Therapy Treatment Outcome for Adolescents with Antisocial Behaviours: A Retrospective Study in Western Australian Families. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(8):1310. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081310

Chicago/Turabian StyleNuntavisit, Leartluk, and Mark Robert Porter. 2025. "The Influence of Therapist Adherence on Multisystemic Therapy Treatment Outcome for Adolescents with Antisocial Behaviours: A Retrospective Study in Western Australian Families" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 8: 1310. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081310

APA StyleNuntavisit, L., & Porter, M. R. (2025). The Influence of Therapist Adherence on Multisystemic Therapy Treatment Outcome for Adolescents with Antisocial Behaviours: A Retrospective Study in Western Australian Families. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(8), 1310. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081310