Abstract

Brief family support interventions may be an effective and acceptable option when demands on services and pressures on families can often mean intensive, long-term family support interventions are an inefficient and unappealing course of action. The purpose of this scoping review was to better understand the nature of non-medical brief interventions targeted at parents and families experiencing adversity or challenging circumstances that may lead them to seek support from family services. We used a systematic search and selection process to identify publications (papers or webpages) about brief interventions for parents and families within three academic databases and 70 websites. Publications were in scope if the interventions were targeted to parents and families, were non-medical in nature, and were brief (no longer than 10 h duration, or up to four sessions). We identified 78 papers and webpages eligible for inclusion in this scoping review, covering 46 brief interventions. Data were extracted by two researchers and charted in a spreadsheet. Most interventions were delivered in the mental health sector, followed by the education, and then community or family services sector, and most often in a clinical setting. Intervention duration varied, ranging from 45 min to a two-day workshop, and were usually aimed at improving the mental health of children and young people. Interventions were delivered to groups of parents, followed by whole families or individual parents. This review highlights the pressing need for high-quality evaluations of brief interventions for family support, and given the diversity of delivery modes, durations and conceptualisation of ‘brief intervention’ in the field and literature, further synthesis of the evidence through systematic reviews is required. This paper advances understanding and clarity on how brief interventions may be beneficial for families experiencing adversity, yet further evaluation and systematic review for acceptability and efficacy is required.

1. Introduction

Families seeking support services can be offered a range of options, some of which will involve brief interventions to provide support and inform parents quickly and efficiently. Brief interventions are typically time-limited, content-limited and use specific strategies to help clients alleviate immediate needs or to initiate interactions between client and professionals. Brief interventions may also be referred to as ‘simple advice’, ‘minimal interventions’, ‘brief counselling’ or ‘short-term counselling’ [1] (p. 3). Brief interventions can be used stand-alone or in conjunction with other interventions and generally address specific problems or goals rather than larger concerns [1]. With the focus on a specific objective and client-centredness, brief interventions can provide a quick avenue for building client relationships [1] and may also have a social benefit associated with increasing client engagement with support. This may lend brief interventions to services being able to provide support to families in a prompt and efficient way, overriding some of the practical challenges and delays sometimes associated with traditional interventions offering longer-term comprehensive treatment approaches.

There is no universally agreed definition of what constitutes a brief intervention [2]. Generally, brief interventions appear not to exceed four or five sessions, although the optimal number of sessions is unclear [3]. A systematic review in the area of childhood anxiety treatment operationalised an intervention as ‘brief’ if it included at least 50% fewer total sessions than standard treatment, as ‘intensive’ if the number of sessions and intervention duration is reduced versus standard treatment (e.g., one 180 min session treatment for specific phobia), and ‘concentrated’ if the intervention has a standard number of sessions, but sessions are delivered in a shorter time period (e.g., 12 sessions of CBT delivered in 6 weeks) [4]. Brief interventions have also reportedly been as brief as a 30 s behavioural change intervention to more than 30 min for an extended brief behavioural intervention [5]. In a systematic review of universal family and child health services, a duration limit of four sessions was within the review scope [2].

There is systematic review evidence to suggest brief interventions may result in improved child outcomes; however, the scope of these reviews is largely focused on populations with mental health concerns [6,7,8,9,10,11,12]. While this provides some indication of suitability and effectiveness of brief interventions within the mental health setting, these reviews provide limited understanding of the applicability of brief interventions for the diverse range of families, in addition to those with mental health concerns, that may engage with family support services. A better understanding of the nature of brief interventions for a broader range of populations would support an understanding of the potential for this type of intervention to be effectively adopted to meet the needs of families seeking support. To address the gap in research, this scoping review aims to examine the purpose, populations, settings, dose and delivery of brief interventions for parents and families that are likely to attend family support services. While there is currently no evidence indicating the level of demand for brief interventions across family services, there is widespread implementation and uptake of this modality. With brief interventions increasingly adopted across family services to provide more immediate support, this review offers a unique opportunity to describe brief intervention approaches in family support services.

2. Method

2.1. Review Design

We conducted a scoping review to develop a picture of brief interventions used with families. We drew on the scoping review framework developed by Arksey and O’Malley [13] and refined by Levac and colleagues [14] for mapping out the nature of and evidence for brief interventions for families needing support, which has not been extensively reviewed. This guided our approach to conducting the scoping review, including identification of the research question, the relevant literature, publication selection, publication charting, and the collation, summary and reporting of publications. While we adopted the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA-ScR), the checklist was not registered.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

Any study design reporting parent, child, family or service outcomes was in scope. Searches within databases were limited to the English language and the year 2018 onwards to capture recent research, but no year limits were applied to webpage searches. Brief interventions were in scope if they were synchronous and targeted parents or families experiencing adversity, including the following: child maltreatment; housing instability or being priced out of stable housing; mental health concerns; emotional or behavioural concerns; under- or unemployment; family violence; community violence; disability; alcohol or other drug misuse; eating disorders; incarceration; school attendance concerns; sleep and settling concerns; and attachment issues. Interventions delivered to children without their parents involved, or interventions aimed at adults who were not identified as parents, were excluded. Interventions relating to medical concerns, such as cancer or diabetes, were ineligible. The interventions could be delivered by professionals, paraprofessionals, peers, or volunteers in group, one-to-one, or dyad (e.g., couple, parent–child) formats. Delivery could be in-person, via telephone or teleconference, text-based, or web-based.

As there is no uniform duration for brief interventions in the literature, we took the approach of including interventions of up to four sessions [2] or up to 10 h duration [15], including single-session interventions. Interventions were excluded from the review if duration in sessions or hours was not reported.

2.3. Information Sources

We included published and unpublished studies, webpages, practice guides, and programme manuals that provided some detail regarding brief interventions for parents or families. Only online sources were included, while books, book chapters and theses were excluded. We selected bibliographic databases and search engines suitable for scoping reviews in the social sciences field [16], and conducted a comprehensive search across PsychInfo, Cumulative Index for Nursing and Allied Health (CINAHL), SocINDEX on 3 May 2023 and 70 websites in May 2023 (see Appendix A for a list of organisation websites searched). We also invited our colleagues with expertise in family support services to suggest potential studies and brief interventions for consideration in this review.

2.4. Search Strategy

We developed a priori search terms designed to identify various types of brief interventions, including single-session and walk-in approaches, brief workshops, and casual and low-intensity programmes (see Appendix B). Search terms were also used to identify interventions specifically for parents, caregivers and families. Truncation symbols were used to identify all possible variations of the key terms with the Boolean ‘OR’ criterion, with the search initially designed to identify individual terms. Combinations of the key terms were subsequently searched using the Boolean ‘AND’ criterion.

2.5. Selection and Extraction

Publications identified through database and website searches and by expert recommendation were imported into Endnote bibliographic software, Version 21 to support our screening processes. Duplicates were removed and then titles and abstracts (or website excerpts where applicable) were screened against pre-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Full text was obtained for all publications that were screened in, and these were subsequently reviewed by three researchers from the review team (EA, CH and ZP). Uncertainties as to eligibility were resolved by consultation with the full review team.

2.6. Data Charting

A data charting spreadsheet was developed to guide and chart the systematic extraction of information from all included publications. The extraction categories included intervention name, target outcome, country, service sector, target population, intervention duration/dose, setting, structure, mode and a summary of the intervention. Three members of the review team (EA, CH and ZP) extracted key details from full text publications into spreadsheet categories and collaborated with the full review team to resolve any ambiguous decisions by consensus.

3. Results

3.1. Search and Selection Results

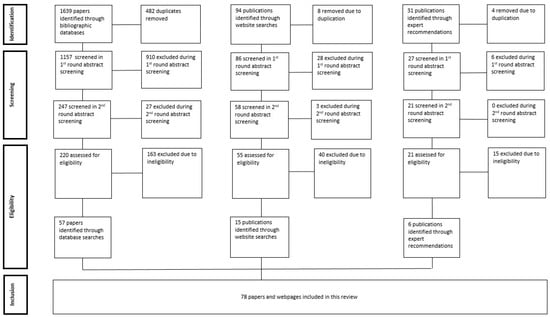

An initial 1764 publications (inclusive of articles and webpages) were identified through database and website searches and through expert recommendations. After the initial screening process, 296 publications were assessed in detail for final eligibility, with a total of 78 publications retained. This included 57 papers from bibliographic databases, 15 websites, and 6 publications through expert recommendations. The strategy for study selection is depicted in Figure 1, which outlines how the PRISMA guidelines for inclusion of studies was applied. Study characteristics, intervention and outcomes are summarised in Table 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of the search and selection process.

Table 1.

Characteristics, interventions and outcomes of included publications.

3.2. Service and Setting Contexts for Brief Interventions

From the 78 publications examined in this review, brief interventions were predominantly reported in the mental health sector (n = 24), the education sector (n = 15) and community or family services sectors (n = 11). We found 10 publications reporting interventions in the health sector, primarily in maternal health and antenatal care. Two interventions were delivered in the disability sector, and one each in child protection and corrections. One publication was not sector specific.

Interventions were primarily delivered in a clinical setting, such as a hospital, therapeutic clinic or treatment centre (n = 29). Interventions delivered in universities (n = 10), community service agencies (n = 7), the home (n = 4) and community settings (n = 5) were also reported. A further six were delivered online through teleconferencing and four were delivered in schools.

3.3. Purpose and Domains of Brief Interventions

Most brief interventions aimed to improve the mental health of children and young people. Some publications reported interventions targeting mental health and psychological symptoms broadly (n = 14), while others named specific child mental health conditions such as anxiety (n = 6), depression (n = 3) and suicidal thoughts and behaviours (n = 1). Some interventions targeted externalising behaviours of children and young people, including child behaviour in general (n = 8), and use of alcohol and other drugs (n = 5). Others were intended to improve child outcomes such as eating disorders (n = 2), sleep issues (n = 3), executive functioning (n = 1) and overall development (n = 1).

Some interventions targeted parent mental health including stress, distress, worry (n = 4), general mental health (n = 2) and conditions such as anxiety (n = 3) and depression (n = 3). Parenting, including positive parenting, parenting competence and dysfunctional parenting (n = 8) were also the focus of several interventions. Various interventions aimed to build specific parenting skills in the areas of parenting self-efficacy (n = 7), parent knowledge (n = 2), self-esteem (n = 1), parent psychological flexibility (n = 2), parent attitudes (n = 1), reflective functioning (n = 1) and mentalisation (n = 2).

Some publications described brief interventions targeting family-level outcomes including family worry and confidence (n = 1), family conflict (n = 2) and family functioning (n = 2), or improving family and/or parent–child relationships (n = 9). One paper targeted increasing joint attention in a parent–child dyad. Brief interventions were also used to motivate and enhance engagement of families and children in further interventions (n = 5).

3.4. Families Participating in Brief Interventions

The populations targeted in most interventions were people with mental health concerns (child mental health = 23 publications, parental mental health = 7, parent distress = 4). Children with disabilities were the target population in 13 publications, including children with Down’s Syndrome, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and Autistic children. People with alcohol and other drug concerns were the target population of eight interventions, and three sources described interventions aimed broadly at vulnerable or at-risk populations, while others targeted low income (n = 3) and families priced out of housing (n = 1). Some interventions targeted families experiencing conflict or intimate partner or family violence (n = 4) and one targeted refugees of war. One intervention was aimed at pregnant adolescents, three targeted children and young people with eating disorders, and three interventions were for children with sleep disorders.

Many interventions targeted broad age ranges from young children to early adolescence. Thirteen interventions targeted families of children aged from 7 to 14 years, or 4 to 15 years, while three interventions targeted families of children aged 0 to 18 years. However, some interventions had narrow child age groups, specifically for adolescents, usually stating 12 to 19 years (n = 9), newborns and infants (n = 3) or toddler and preschool years (n = 3). There were also four publications on brief interventions delivered during the antenatal period.

3.5. Duration of Brief Interventions

There was considerable variation in the duration of brief interventions within the scope of our selection, which was limited to interventions delivered over a maximum of four sessions or up to 10 h duration. Several interventions consisted of one session only (n = 16) which ranged from 45 min to a two-day workshop. A further 16 interventions consisted of one primary session with an add-on, which was either a refresher session, text message to reinforce content, an individual family-member session or coaching phone calls. The remaining interventions involved two to four core sessions of widely varying duration.

Single-session approaches were adopted by several brief interventions identified in this review. Single-session intervention (SSI) is an approach to therapy and service delivery which promotes a client-centred and collaborative approach when working with individuals, couples and families. In the literature, it is referred to as Single Session Therapy, Single Session Work and Single Session Thinking. While there are some interventions that use the name single-session, these may be one-off encounters with the client (e.g., a workshop) that do not follow the SSI approach. SSI is underpinned by research and clinical findings suggesting many clients seeking therapy only attend one session and significantly benefit from it [81]. This does not mean that SSI is restricted to one session, but that each session, particularly the first one, is viewed as potentially the final session. Thus, the aim of each session is to maximise therapeutic benefits for the client while leaving an opportunity for having additional sessions, if required. The typical structure of SSI involves having one session which is followed up with a phone call a few weeks later to ascertain how the client is going and whether further support is required. A decision whether to have an additional session(s) is based on discussions between the practitioner and the client [82].

3.6. Delivery of Brief Interventions

Various delivery structures were identified, sometimes with multiple modes used in the one intervention. Interventions were most often delivered to groups of parents (n = 22), the whole family, or multiple family members (n = 15), individual parents (n = 15), groups of couples (n = 3), an individual couple (n = 1), individual parent–child dyads (n = 5), groups of parent–child dyads (n = 1), whole family plus teacher (n = 1), parent/family session plus child session (n = 3), whole family session plus child session (n = 1), and parent session plus parent–child session (n = 1). These were a mix of individual and group level interventions. There were also some interventions that used various delivery structures depending on which family members opted to attend any given session (n = 7).

The intervention delivery approaches identified more often in the review included psychoeducation, motivational interviewing, parent coaching and cognitive behavioural therapy, with some delivering a manualised, structured approach and others tailoring sessions to suit client-identified needs or goals.

4. Discussion

The purpose of this scoping review was to map the breadth and nature of the literature describing brief interventions for families experiencing circumstances that lead them to seek formalised support. Within this population, a wide range of brief interventions were identified with diverse applications, dosage, targeted outcomes and delivery approaches. This review indicates brief interventions in the provision of family support are implemented internationally and predominantly in the mental health field, targeting the mental health of children and young people. Brief interventions are also widely implemented across community or family services, education, maternal health and antenatal care, disability, child protection and corrections. However, there may be limits to the severity of challenges that can be addressed with brief interventions. While not examined in the current review, there is concordance in the literature that brief interventions are suitable for mild to moderate difficulties and are typically considered to be low intensity [83]. Some authors go so far as to suggest [84] that brief interventions will not help clients with complex or acute needs.

The brief interventions described in publications identified in the current review ranged from well-known, researched, manualised and prescribed programmes, to novel innovations and flexible, tailored approaches with room to expand the amount and type of assistance according to family needs and interests. There was considerable variation in how much intervention families received, and how interventions were delivered, including interventions that combined individual with group work, didactic learning with self-directed learning, online with face-to-face delivery, and family-level supports with parent-level supports. Clinical and therapeutic approaches were employed in several of the interventions, sometimes using more than one approach in the same intervention. Consideration should be given to the suitability of brief interventions where there is a high risk to health and safety. In these cases, some triaging by services may be warranted to determine suitability for brief interventions. Given the wide variation in intervention delivery approaches, there is no clear indication in the literature as to an ideal brief intervention approach. The ideal intervention approach is likely to be governed by a range of factors, including family context, and the severity of the presenting issues.

While most brief interventions included in this review focused on addressing mental health concerns in clinical, mental health settings, there were some examples of use in broader populations and settings. For example, several brief interventions targeted families experiencing a diverse range of concerns or vulnerabilities, or in community and school settings. Thus, in addition to the mental health sector, there are some indications of the applicability of brief interventions to the broader family services sector. The interventions in this review typically involved groups of parents attending an intervention, and often one parent only or in some cases multiple family members, but infrequently involved couples, parent–child dyads or parallel sessions with children and younger people alongside parents. The focus on parents as the agent of change in the brief interventions reported here is consistent with the parenting support approach taken in many family services, suggesting brief interventions have further applicability in this context.

In services where there is potential for a moderate or high number of families to attend once or infrequently, single-session interventions may be a viable option. Some common elements of SSIs include identifying the client’s goals, checking periodically whether the session is on track, providing feedback and focusing on responding to the client’s goals [85]. In many cases, these elements could be sufficient to address immediate family needs, while remaining open to further support provision or onward referral. Single-session approaches therefore have the potential to capitalise on an initial interaction to provide support, in what may be the only opportunity to address families’ goals. Such an approach promotes the likelihood that families walk away from a service with something helpful, regardless of whether they return in future. As often is the circumstance of vulnerable families, their concerns, needs and challenges may come and go or resurface over time [86]. In SSIs, intervention does not cease when all challenges are resolved, but instead the end of an intervention signals that the client is better able to self-manage their current concern. When considering ‘how much is enough’ of an intervention, the duration is less significant than whether the intervention has been sufficient in helping the client address their immediate needs [86].

Another advantage to the single-session way of working is that it can be viewed as a philosophical approach rather than a specific intervention or programme, as there is no prescribed type of therapy within SSI and practitioners can use their own therapeutic modality while delivering the session in a way that is consistent with single-session thinking [85]. This flexibility allows agencies and practitioners to employ practices that suit them and their clients within the single-session model. Several publications included in this scoping review noted the benefits of SSIs for supporting engagement as an approach that could be used with the intention of providing immediate assistance or supporting motivation to attend a further service. The objective of a single session could entail providing families with as much knowledge and relevant strategies and skills as possible, as early as possible. Several of the interventions included in this scoping review appeared to adopt an approach congruent with the SSI model, such as when families participate in an initial session or two involving motivational interviewing to support engagement, and this is then followed up with feedback and coaching to support continued change.

Based on the literature, the single-session philosophy shares some similar features with solution-focused therapy, as both methods focus less on identifying problems and concerns and more on what can be implemented to achieve an immediate solution to a goal, possibly drawing on past successes and strengths. This has been identified by others as one of the favourable qualities of SSIs when used to support First Nations people [70], who underline the value of the oral tradition and deep listening in therapeutic conversation with Indigenous families when using the single session approach. Other potential strengths of a single-session approach include the focus on clients’ needs and resources rather than on intake processes and assessment completion. Meeting people where they are at and letting clients take the lead in the conversations were also reported advantages [70]. Practices seen to support a good experience with single-session interventions included deep listening, respecting the oral tradition, not using jargon but instead using the language of the family and not approaching the session as an expert [70].

Limitations of This Review

We imposed several pragmatic limits to our search process (e.g., English language papers only, a definition of ‘brief intervention’, and publications from 2018 onwards) which may have meant we missed key papers or websites of relevance to the aims of this review. Additionally, our databases were predominantly in the fields of health and mental health, and there may be additional perspectives from other applied social sciences lacking in this review. Broader search parameters in future reviews may contribute to furthering understanding of what works and for whom, beyond the conclusion drawn from our review.

5. Conclusions

Brief interventions appear to sufficiently address the immediate needs of families seeking formal support and may be particularly useful for enhancing motivation and engagement with supports. Their application may, however, be better suited to clients with low- to moderate-level needs or risks.

While the publications included in this review suggest brief interventions that have more frequently been used in the context of mental health services, there are also examples of use in family support services with families experiencing a range of challenges. Brief interventions, particularly those with single-session approaches, may complement the range of approaches available in family support services. Given the potential for variations in definitions of brief intervention, any policies recommending the use of brief interventions should ideally articulate how brief interventions are to be conceptualised, in terms of duration, scope, purpose and delivery. Routine evaluation of brief interventions is particularly important given the variability in what is conceptualised as a brief intervention, and when new approaches are designed or adapted.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: M.M. and G.-M.S.; Data extraction: C.H., Z.P. and E.A.; Writing (original draft and preparation): G.-M.S., M.M. and V.H.; Writing (review and editing): C.W., G.-M.S., M.M. and V.H.; Project administration: M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Victorian Government, Australia. Victorian Government.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Organisation websites searched.

Table A1.

Organisation websites searched.

| Organisation | Website |

|---|---|

| Act for Kids | https://www.actforkids.com.au accessed on 2 May 2023 |

| Allright | https://www.allright.org.nz/tools/parenting-courses accessed on 10 May 2023 |

| Anglicare Australia | https://www.anglicare.asn.au accessed on 9 May 2023 |

| Anglicare NSW & ACT | https://www.anglicare.com.au/ accessed on 9 May 2023 |

| Anglicare NT | https://www.anglicare-nt.org.au/ accessed on 9 May 2023 |

| Anglicare QLD | https://anglicarecq.org.au/ accessed on 9 May 2023https://www.anglicanchurchsq.org.au/anglicare accessed on 4 May 2023https://www.anglicarenq.org.au/ accessed on 4 May 2023 |

| Anglicare SA | https://anglicaresa.com.au/ accessed on 4 May 2023 |

| Anglicare Tasmania | https://www.anglicare-tas.org.au/ accessed on 9 May 2023 |

| Anglicare Victoria | https://www.anglicarevic.org.au/ accessed on 4 May 2023 |

| Anglicare WA | https://www.anglicarewa.org.au/ accessed on 9 May 2023 |

| Australian Childhood Foundation | https://www.childhood.org.au accessed on 4 May 2023 |

| Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet | https://healthinfonet.ecu.edu.au accessed on 3 May 2023 |

| Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies | https://aiatsis.gov.au/research accessed on 3 May 2023 |

| Australian Institute of Family Studies | https://aifs.gov.au accessed on 3 May 2023 |

| Australian Institute of Health and Welfare | https://www.aihw.gov.au accessed on 3 May 2023 |

| Berry Street | https://www.berrystreet.org.au/ accessed on 2 May 2023 |

| beyondblue | https://www.beyondblue.org.au accessed on 4 May 2023 |

| Black Dog Institute | https://www.blackdoginstitute.org.au accessed on 4 May 2023 |

| BlueKnot Foundation | https://blueknot.org.au accessed on 4 May 2023 |

| Body Matters Australia | https://bodymatters.com.au accessed on 4 May 2023 |

| Bouverie Centre | https://www.latrobe.edu.au/research/centres/health/bouverie accessed on 2 May 2023 |

| Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service (CAMHS) ACT | https://www.canberrahealthservices.act.gov.au/services-and-clinics/services/child-and-adolescent-mental-health-service-camhs-community-teams accessed on 4 May 2023 |

| CAMHS NSW | https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/mentalhealth/Pages/services-camhs.aspx accessed on 4 May 2023 |

| CAMHS SA | https://www.wchn.sa.gov.au/our-network/camhs accessed on 4 May 2023 |

| CAMHS Tasmania | https://www.health.tas.gov.au/health-topics/mental-health/tasmanias-mental-health-system/child-and-adolescent-mental-health-service accessed on 4 May 2023 |

| CAMHS WA | https://cahs.health.wa.gov.au/Our-services/Mental-Health accessed on 4 May 2023 |

| Canadian Child Welfare Research Portal | https://cwrp.ca accessed on 10 May 2023 |

| CatholicCare ACT | https://catholiccare.cg.org.au/ accessed on 9 May 2023 |

| CatholicCare Central QLD | https://catholiccarecq.com/ accessed on 9 May 2023 |

| CatholicCare NSW | https://www.catholiccare.org accessed on 9 May 2023 |

| CentaCare SA | https://www.cccsa.org.au/ accessed on 9 May 2023 |

| CatholicCare Tasmania | https://catholiccaretas.org.au/ accessed on 9 May 2023 |

| CatholicCare Victoria | https://www.catholiccarevic.org.au/ accessed on 9 May 2023 |

| Centre for Excellence in Child and Family Welfare | https://www.cfecfw.asn.au accessed on 10 May 2023 |

| Centre for Integrative Health | https://cfih.com.au accessed on 4 May 2023 |

| Child Welfare Information Gateway | https://www.childwelfare.gov accessed on 10 May 2023 |

| Communicare | https://www.communicare.org.au/Children-Youth-Family/Parenting-Services/Parenting-Support-Services accessed on 4 May 2023 |

| COPE | https://www.cope.org.au accessed on 4 May 2023 |

| Child and Youth Mental Health Service (CYMHS) QLD | https://www.childrens.health.qld.gov.au/services/mental-health accessed on 4 May 2023 |

| CYMHS Victoria | https://www.alfredhealth.org.au/services/child-youth-mental-health-service accessed on 4 May 2023https://www.easternhealth.org.au/mental-health-3/infants-children-and-youth-0-25/ accessed on 4 May 2023 |

| Drummond Street Services | https://ds.org.au/ accessed on 2 May 2023 |

| Family Life | https://www.familylife.com.au accessed on 2 May 2023 |

| ForWhen | https://forwhenhelpline.org.au accessed on 4 May 2023 |

| Headspace | https://headspace.org.au/, Accessed on 2 May 2023 |

| Health Navigator NZ | https://www.healthnavigator.org.nz/healthy-living/p/parenting-resources-courses-and-support/ accessed on 10 May 2023 |

| JewishCare NSW | https://jewishcare.com.au accessed on 9 May 2023 |

| JewishCare QLD | http://www.jcareqld.com/ accessed on 9 May 2023 |

| JewishCare Victoria | https://www.jewishcare.org.au/ accessed on 9 May 2023 |

| Lowitja Institute | https://www.lowitja.org.au accessed on 3 May 2023 |

| MacKillop Family Services | https://www.mackillop.org.au accessed on 3 May 2023 |

| Meerlinga | https://www.meerilinga.org.au/parenting-courses-services/ accessed on 4 May 2023 |

| Mental Health Beacon | https://www.latrobe.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/1153959/Mental-Health-Beacon-Project-Report-March-2015.pdf accessed on 4 May 2023 |

| National Society for the Prevention of Child Cruelty | https://www.nspcc.org.uk/, Accessed on 10 May 2023 |

| Ngala | https://www.ngala.com.au accessed on 9 May 2023 |

| Orygen | https://www.orygen.org.au accessed on 3 May 2023 |

| PANDA | https://panda.org.au/ accessed on 4 May 2023 |

| Relationship Australia | https://relationships.org.au accessed on 3 May 2023 |

| SNAICC | https://www.snaicc.org.au accessed on 3 May 2023 |

| Social Care Institute for Excellence | https://www.scie.org.uk accessed on 10 May 2023 |

| Turning Point | https://www.turningpoint.org.au accessed on 4 May 2023 |

| Uniting SA | https://unitingsa.com.au/ accessed on 10 May 2023 |

| Uniting WA | https://unitingwa.org.au/ accessed on 9 May 2023 |

| UnitingCare Australia | https://unitingcare.org.au, Accessed on 9 May 2023 |

| Uniting NSW & ACT | https://www.uniting.org/home, Accessed on 9 May 2023 |

| UnitingCare QLD | https://www.unitingcareqld.com.au/ accessed on 9 May 2023 |

| Uniting Victoria & Tasmania | https://www.unitingvictas.org.au/services/ accessed on 9 May 2023 |

| Wanslea | https://www.wanslea.org.au/families-and-children/parents-and-grandparent-carers#Parenting-support accessed on 9 May 2023 |

Appendix B

Table A2.

Search Terms.

Table A2.

Search Terms.

| 1 | Brief N3 (educat* or interven* or therap* or counsel* or facilit* or program* or help* or assist* or guid* or navigat* or helpline* or support* or advisor* or advice or consult* or helpline* or practice* or coach* or interviewing) |

| 2 | Walk-in N3 (educat* or interven* or therap* or counsel* or facilit* or program* or help* or assist* or guid* or navigat* or helpline* or support* or advisor* or advice or consult* or helpline* or practice* or coach* or interviewing) |

| 3 | Drop-in N3 (educat* or interven* or therap* or counsel* or facilit* or program* or help* or assist* or guid* or navigat* or helpline* or support* or advisor* or advice or consult* or helpline* or practice* or coach* or interviewing) |

| 4 | Short N3 (educat* or interven* or therap* or counsel* or facilit* or program* or help* or assist* or guid* or navigat* or helpline* or support* or advisor* or advice or consult* or helpline* or practice* or coach* or interviewing) |

| 5 | Casual N3 (educat* or interven* or therap* or counsel* or facilit* or program* or help* or assist* or guid* or navigat* or helpline* or support* or advisor* or advice or consult* or helpline* or practice* or coach* or interviewing) |

| 6 | Low-intensity N3 (educat* or interven* or therap* or counsel* or facilit* or program* or help* or assist* or guid* or navigat* or helpline* or support* or advisor* or advice or consult* or helpline* or practice* or coach* or interviewing) |

| 7 | Workshop* N3 (educat* or interven* or therap* or counsel* or facilit* or program* or help* or assist* or guid* or navigat* or helpline* or support* or advisor* or advice or consult* or helpline* or practice* or coach* or interviewing) |

| 8 | Single-session N3 (educat* or interven* or therap* or counsel* or facilit* or program* or help* or assist* or guid* or navigat* or helpline* or support* or advisor* or advice or consult* or helpline* or practice* or coach* or interviewing) |

| 9 | One-off N3 (educat* or interven* or therap* or counsel* or facilit* or program* or help* or assist* or guid* or navigat* or helpline* or support* or advisor* or advice or consult* or helpline* or practice* or coach* or interviewing) |

| 10 | One-session N3 (educat* or interven* or therap* or counsel* or facilit* or program* or help* or assist* or guid* or navigat* or helpline* or support* or advisor* or advice or consult* or helpline* or practice* or coach* or interviewing) |

| 11 | Light-touch N3 (educat* or interven* or therap* or counsel* or facilit* or program* or help* or assist* or guid* or navigat* or helpline* or support* or advisor* or advice or consult* or helpline* or practice* or coach* or interviewing) |

| 12 | Parent* or carer* or caregiver* or care-giver* or mother* or father* or family or families or mum* or dad* or mom* or maternal or paternal or stepparent* or guardian* or kin or kith or mob* |

| 13 | 1–11/or |

| 14 | 12 and 13 |

* In a Boolean search the asterisk is a truncation to identify variations of a word.

References

- Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Brief interventions and brief therapies for substance abuse. In Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Servies; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: Rockville, MD, USA, 1999; Volume 34. [Google Scholar]

- Newham, J.J.; McLean, K.; Ginja, S.; Hurt, L.; Molloy, C.; Lingam, R.; Goldfeld, S. Brief evidence-based interventions for universal child health services: A restricted evidence assessment of the literature. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winters, K.C.; Lee, S.; Botzet, A.; Fahnhorst, T.; Nicholson, A. One-year outcomes and mediators of a brief intervention for drug abusing adolescents. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2014, 28, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoll, R.D.; Pina, A.A.; Schleider, J. Brief, non-pharmacological, interventions for pediatric anxiety: Meta-analysis and evidence base status. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2020, 49, 435–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Behaviour Change: Individual Appoach; NICE: Ra’anana, Israel, 2014; Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph49/chapter/Recommendations#recommendation-9-deliver-very-brief-brief-extended-brief-and-high-intensity-behaviour-change (accessed on 3 May 2023).

- Schmit, E.L.; Schmit, M.K.; Lenz, A.S. Meta-analysis of solution-focused brief therapy for treating symptoms of internalizing disorders. Couns. Outcome Res. Eval. 2017, 7, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, K.-S.; Eads, R.; Lee, M.Y.; Wen, Z. Solution-focused brief therapy for behavior problems in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis of treatment effectiveness and family involvement. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2021, 120, 105620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingoldsby, E.M. Review of interventions to improve family engagement and retention in parent and child mental health programs. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2010, 19, 629–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, S.; Patton, G. Engaging families in the management of adolescent self-harm. Evid.-Based Ment. Health 2018, 21, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hymmen, P.; Stalker, C.A.; Cait, C.A. The case for single-session therapy: Does the empirical evidence support the increased prevalence of this service delivery model? J. Ment. Health 2013, 22, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleider, J.L.; Weisz, J.R. Little treatments, promising effects? Meta-analysis of single-session Interventions for youth psychiatric problems. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2017, 56, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleider, J.L.; Dobias, M.L.; Sung, J.Y.; Mullarkey, M.C. Future directions in single-session youth mental health interventions. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2020, 49, 264–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victorian Department of Families, Fairness and Housing. Individual, Child and Family Support 31435; Department of Families, Fairness and Housing: Melbourne, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jolley, R.J.; Lorenzetti, D.L.; Manalili, K.; Lu, M.; Quan, H.; Santana, M.J. Protocol for a scoping review study to identify and classify patient-centred quality indicators. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e013632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesterfield, J.A.; Porzig-Drummond, R.; Stevenson, R.J.; Stevenson, C.S. Evaluating a brief behavioral parenting program for parents of school-aged children with ADHD. Parent. Sci. Pract. 2021, 21, 216–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Mahen, H.A.; Ramchandani, P.G.; King, D.X.; Lee-Carbon, L.; Wilkinson, E.L.; Thompson-Booth, C.; Ericksen, J.; Milgrom, J.; Dunkley-Bent, J.; Halligan, S.L.; et al. Adapting and testing a brief intervention to reduce maternal anxiety during pregnancy (ACORN): Report of a feasibility randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooney, M.R.; Short, M.A.; Gradisar, M. An open trial of bedtime fading for sleep disturbances in preschool children: A parent group education approach. Sleep Med. 2018, 46, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villarreal, Y.R.; Spellman, M.L.; Prudon, J.; Northrup, T.F.; Berens, P.D.; Blackwell, S.; Velasquez, M.M.; Stotts, A.L. A brief, hospital-initiated motivational interviewing and acceptance and commitment therapy intervention to link postpartum mothers who use illicit drugs with treatment and reproductive care: A case report. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 2021, 28, 92–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, K.; Lake, J.; Steel, L.; Bryce, K.; Lunsky, Y. ACT processes in group intervention for mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2018, 48, 2740–2747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahs, A.D.; Dixon, M.R.; Paliliunas, D. Randomized controlled trial of a brief acceptance and commitment training for parents of individuals diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2019, 12, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunsky, Y.; Fung, K.; Lake, J.; Steel, L.; Bryce, K. Evaluation of acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) for mothers of children and youth with autism spectrum disorder. Mindfulness 2018, 9, 1110–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyer, D.N.; Page, A.R.; McMakin, D.Q.; Murrell, A.R.; Lester, E.G.; Walker, H.A. The Impact of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy on Positive Parenting Strategies Among Parents Who Have Experienced Relationship Violence. J. Fam. Violence 2018, 33, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jewell, C.; Wittkowski, A.; Collinge, S.; Pratt, D. A brief cognitive behavioural intervention for parents of anxious children: Feasibility and acceptability study. Child Youth Care Forum 2023, 52, 661–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giallo, R.; Fogarty, A.; Savopoulos, P.; Cox, A.; Toone, E.; Williams, K.; Jones, A.; Treyvaud, K. Capturing the experiences of clinicians implementing a new brief intervention for parents and children who have experienced family violence in Australia. Health Soc. Care Community 2022, 30, e1599–e1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogarty, A.; Treyvaud, K.; Savopoulos, P.; Jones, A.; Cox, A.; Toone, E.; Giallo, R. Facilitators to engagement in a mother–child therapeutic intervention following intimate partner violence. J. Interpers. Violence 2022, 37, 1796–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moudi, Z.; Talebi, B.; Pour, M.S. Effect of a brief training program for primigravid adolescents on parenting self-efficacy and mother-infant bonding in the southeast of Iran. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2020, 32, 20170092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.H.; Turbitt, E.; Muschelli, J.; Leonard, L.; Lewis, K.L.; Freedman, B.; Muratori, M.; Biesecker, B.B. Feasibility of coping effectiveness training for caregivers of children with autism spectrum disorder: A genetic counseling intervention. J. Genet. Couns. 2018, 27, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGoron, L.; O’Neal, T.; Savastano, G.E.; Roberts, K.L.; Richardson, P.A.; Bocknek, E.L. Creating Connections: A Feasibility Study of a Technology-Based Intervention to Support Mothers of Newborns during Pediatric Well-Visits. Clin. Pract. Pediatr. Psychol. 2023, 11, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zachry, A.H.; Jones, T.; Flick, J.; Richey, P. The Early STEPS pilot study: The impact of a brief consultation session on self-reported parenting satisfaction. Matern. Child Health J. 2021, 25, 1923–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelmsen-Langeland, A.; Aardal, H.; Hjelmseth, V.; Fyhn, K.H.; Stige, S.H. An Emotion Focused Family Therapy workshop for parents with children 6–12 years increased parental self-efficacy. Emot. Behav. Difficulties 2020, 25, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, P.; Renelli, M.; Stillar, A.; Streich, B.; Lafrance, A. Long-term outcomes of a brief emotion-focused family therapy intervention for eating disorders across the lifespan: A mixed-methods study. Can. J. Couns. Psychother. 2020, 54, 130–149. [Google Scholar]

- Foroughe, M.; Soliman, J.; Bean, B.; Thambipillai, P.; Benyamin, V. Therapist adaptations for online caregiver emotion-focused family therapy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pers.-Centered Exp. Psychother. 2022, 21, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroughe, M.; Browne, D.T.; Thambipillai, P.; Cordeiro, K.; Muller, R.T. Brief emotion-focused family therapy: A 12-month follow-up study. J. Marital. Fam. Ther. 2023, 49, 394–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldman, J.S.; Zhou, Y.; Krug, C.W.; Wilson, M.N.; Shaw, D.S. Indirect effects of the Family Check-Up on youth extracurricular involvement at school-age through improvements in maternal positive behavior support in early childhood. Soc. Dev. 2021, 30, 311–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, S.J.; Marceau, K.; Hernandez, L.; Spirito, A. Is it selection or socialization? Disentangling peer influences on heavy drinking and marijuana use among adolescents whose parents received brief interventions. Subst. Abus. Res. Treat. 2019, 13, 1178221819852644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, A.M.; Magee, K.; Stormshak, E.; Ha, T.; Westling, E.; Wilson, M.; Shaw, D. Long-term cross-over effects of the family check-up prevention program on child and adolescent depression: Integrative data analysis of three randomized trials. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2021, 89, 773–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adkins, T.; Reisz, S.; Hasdemir, D.; Fonagy, P. Family Minds: A randomized controlled trial of a group intervention to improve foster parents’ reflective functioning. Dev. Psychopathol. 2021, 34, 1177–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adkins, T.; Luyten, P.; Fonagy, P. Development and preliminary evaluation of Family Minds: A mentalization-based psychoeducation program for foster parents. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2018, 27, 2519–2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoadley, B.; Falkov, A.; Agalawatta, N. The acceptability of a single session family focused approach for children/young people and their parents attending a child and youth mental health service. Adv. Ment. Health 2019, 17, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobham, V.; Radtke, S.; Hawkings, I.; Jordan, M.; Ali, N.R.; Ollendick, T.; Sanders, M. Evaluating a One-Day Parent-Only Intervention in the Treatment of Youth with Anxiety Disorders: Child and Family-Level Outcomes; Research Square: Durham, NC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, O.; Owens, C. Evaluation of Fear-less Triple P in Ireland; International Congress on Evidence-based Parenting Support; ICEPS Conference: Bangkok, Thailand, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Triple P. Fear-Less Triple P; Triple P International Pty Ltd.: Brisbane, Australia, 2020; Available online: www.triplep.net/files/9515/9477/2089/ENG_Fear-Less_Triple_P_LTR.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2023).

- Georg, A.; Kress, S.; Taubner, S. Strengthening mentalizing in a depressed mother of an infant with sleep disorders. J. Clin. Psychol. 2019, 75, 859–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esbjørn, B.H.; Breinholst, S.; Christiansen, B.M.; Bukh, L.; Walczak, M. Increasing access to low-intensity interventions for childhood anxiety: A pilot study of a guided self-help program for Scandinavian parents. Scand. J. Psychol. 2019, 60, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botzet, A.M.; Dittel, C.; Birkeland, R.; Lee, S.; Grabowski, J.; Winters, K.C. Parents as interventionists: Addressing adolescent substance use. J. Subst. Abus. Treat. 2019, 99, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, K.; Sandman, L. Parents as primary sexuality educators for adolescents and adults with Down syndrome: A mixed methods examination of the Home BASE for intellectual disabilities workshop. Am. J. Sex. Educ. 2021, 16, 283–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, C.; Gentilleau, C.; Gemmill, A.W.; Milgrom, J. Improving the mother-infant relationship following postnatal depression: A randomised controlled trial of a brief intervention (HUGS). Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2021, 24, 913–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, K.H.M.; Wyman Battalen, A.; Sellers, C.M.; Spirito, A.; Yen, S.; Maneta, E.; Ryan, C.A.; Braciszewski, J.M. An mHealth approach to extend a brief intervention for adolescent alcohol use and suicidal behavior: Qualitative analyses of adolescent and parent feedback. J. Technol. Hum. Serv. 2019, 37, 255–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, S.G.; Raulston, T.J.; Machalicek, W.; Frantz, R. Caregiver-mediated joint attention intervention. Behav. Interv. 2018, 33, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirehag Nordh, E.L.; Grip, K.; Thorvaldsson, V.; Priebe, G.; Afzelius, M.; Axberg, U. Preventive interventions for children of parents with depression, anxiety, or bipolar disorder: A quasi-experimental clinical trial. Acta Paediatr. 2023, 112, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Bouverie Centre. Mental Health Beacon: Implementing Family Inclusive Practices in Victorian Mental Health Services; The Mental Health Program at the Bouverie Centre, La Trobe University: Melbourne, Australia, 2015; Available online: https://www.latrobe.edu.au/research/centres/health/bouverie/practitioners/specialist-areas/family-inclusion/beacon (accessed on 2 May 2023).

- Nicolson, S.; Carron, S.P.; Paul, C. Supporting early infant relationships and reducing maternal distress with the newborn behavioral observations: A randomized controlled effectiveness trial. Infant Ment. Health J. 2022, 43, 455–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartwright-Hatton, S.; Ewing, D.; Dash, S.; Hughes, Z.; Thompson, E.J.; Hazell, C.M.; Field, A.P.; Startup, H. Preventing family transmission of anxiety: Feasibility RCT of a brief intervention for parents. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2018, 57, 351–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, J.F.; Akins, R.; Miller, E.; Breslau, J.; Gill, S.; Bisi, E.; Schweitzer, J.B. Changing parental knowledge and treatment acceptance for ADHD: A pilot study. Clin. Pediatr. 2023, 62, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CatholicCare. Parenting and Child Development: Parent Coaching; CatholicCare: Sydney, Australia, 2023; Available online: https://www.catholiccare.org/family-youth-children/parenting/child-development-parenting/ (accessed on 9 May 2023).

- Lai, A.Y.K.; Sit, S.M.M.; Thomas, C.; Cheung, G.O.C.; Wan, A.; Chan, S.S.C.; Lam, T.-h. A randomized controlled trial of a positive family holistic health intervention for probationers in Hong Kong: A mixed-method study. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 739418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullum, K.A.; Goodman, S.H.; Garber, J.; Korelitz, K.; Sutherland, S.; Stewart, J. A positive parenting program to enhance positive affect in children of previously depressed mothers. J. Fam. Psychol. 2022, 36, 692–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Triple, P. Primary Care Stepping Stones Triple P: For Parents of a Child with a Disability; Triple P Positive Parenting Program: QLD, Brisbane, Australia, 2022; Available online: https://www.triplep-parenting.net.au/vic-en/free-parenting-courses/which-course-is-right-for-me/stepping-stones-for-parents-of-a-child-with-a-disability/ (accessed on 3 May 2023).

- Zand, D.H.; Bultas, M.W.; McMillin, S.E.; Halloran, D.; White, T.; McNamara, D.; Pierce, K.J. A pilot of a brief positive parenting program on children newly diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. Fam. Process 2018, 57, 901–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carney, T.; Chimbambo, V.; Johnson, K.; Louw, J.; Myers, B. The adaptation of an evidence-based brief intervention for substance-using adolescents and their caregivers. Psychother. Res. 2020, 30, 728–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Distefano, R.; Schubert, E.C.; Finsaas, M.C.; Desjardins, C.D.; Helseth, C.K.; Lister, M.; Carlson, S.M.; Zelazo, P.D.; Masten, A.S. Ready? Set. Go! A school readiness programme designed to boost executive function skills in preschoolers experiencing homelessness and high mobility. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 2020, 17, 877–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittman, C.K.; Burke, K.; Hodges, J. Brief parenting support for parents of teenagers dealing with family conflict: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Child Youth Care Forum 2020, 49, 799–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daire, A.P.; Liu, X.; Tucker, K.; Williams, B.; Broyles, A.; Wheeler, N. Positively impacting maternal stress and parental adjustment through community-based relationship education (RE). Marriage Fam. Rev. 2019, 55, 239–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, J.W.; Almanzar, N.; Chamberlain, L.J.; Huffman, L.; Butze, T.; Marin-Nevarez, P.; Bruce, J.S. School Readiness Coaching in the Pediatric Clinic: Latinx Parent Perspectives. Acad. Pediatr. 2021, 21, 802–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rooks-Ellis, D.L.; Jones, B.; Sulinski, E.; Howorth, S.; Achey, N. The effectiveness of a brief sexuality education intervention for parents of children with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Am. J. Sex. Educ. 2020, 15, 444–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomonsson, B.; Kornaros, K.; Sandell, R.; Nissen, E.; Lilliengren, P. Short-term psychodynamic infant–parent interventions at child health centers: Outcomes on parental depression and infant social–emotional functioning. Infant Ment. Health J. 2021, 42, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akor, B.O.; Moses, L.A.; Baamlong, N.D.; Shedul, L.L.; Haruna, A.S.; Abu, J.M.; Chira, O.U.; Ripiye, N.R.; Abdulkareem, R.A. Effect of counselling on the family function of intimate partner violence victims attending antenatal clinic in a tertiary hospital in North Central Nigeria. S. Afr. Fam. Pract. 2019, 61, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, A.; Dokona, J.; von Doussa, H. Following the river’s flow: A conversation about single session approaches with Aboriginal families. Aust. N. Z. J. Fam. Ther. 2020, 41, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, A.W.C.; Harvey, C.; Fuzzard, S.; O’Hanlon, B. Implementing a family-inclusive practice model in youth mental health services in Australia. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2019, 13, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khatib, B.; Norris, S. A family consultation service: Single session intervention to build the mental health and wellbeing of children and their families. Educ. Child Psychol. 2015, 32, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Bouverie Centre. Walk-in Together Online Sessions; La Trobe University: Melbourne, Australia, 2022; Available online: https://www.latrobe.edu.au/research/centres/health/bouverie/families-and-communities/therapy/walk-in-together-online-sessions (accessed on 2 May 2023).

- BodyMatters. Single Session Intervention; BodyMatters: Mosman, NSW, Australia, 2022; Available online: https://bodymatters.com.au/single-session-intervention/ (accessed on 4 May 2023).

- Bastida-Pozuelo, M.F.; Sánchez-Ortuño, M.M.; Meltzer, L.J. Nurse-led brief sleep education intervention aimed at parents of school-aged children with neurodevelopmental and mental health disorders: Results from a pilot study. J. Spec. Pediatr. Nurs. 2018, 23, e12228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eltanamly, H.; Leijten, P.; van Roekel, E.; Mouton, B.; Pluess, M.; Overbeek, G. Strengthening parental self-efficacy and resilience: A within-subject experimental study with refugee parents of adolescents. Child Dev. 2023, 94, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.J. A case study of solution-focused brief family therapy. Am. J. Fam. Ther. 2020, 48, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopcsó, K.; Láng, A.; Coffman, M.F. Reducing the nighttime fears of young children through a brief parent-delivered treatment—Effectiveness of the Hungarian version of Uncle Lightfoot. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2022, 53, 256–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieverson, C.; Olhaberry, M.; Duarte, J.; Morán-Kneer, J.; Costa, S.; León, M.J.; Valenzuela, S.; Leyton, F.; Honorato, C.; Muzard, A. Beyond the outcomes: Generic change indicators in a video-feedback intervention with a depressed mother and her baby: A single case study. Res. Psychother. Psychopathol. Process Outcome 2022, 25, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganci, M.; Pradel, M.; Hughes, E.K. Feasibility of a parent education and skills workshop for improving response to family-based treatment of adolescent anorexia nervosa. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2018, 51, 358–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rycroft, P.; Young, J. Single session therapy: Capturing the moment. Psychother. Aust. 1977, 4, 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Young, J.; Weir, S.; Rycroft, P. Implementing single session therapy. Aust. N. Z. J. Fam. Ther. 2012, 33, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawker, D.S.J. The case of brief therapy in CAMHS. Clin. Psychol. Forum 2007, 173, 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, B. Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services Review; Tasmanian Department of Health: Hobart, Australia, 2020. Available online: https://www.health.tas.gov.au/sites/default/files/2022-02/Child%20and%20Adolescent%20Mental%20Health%20Services%20Review%20Report.pdf (accessed on 4 May 2023).

- Young, J. Putting single session thinking to work: Conceptual, practical, training, and implementation ideas. Aust. N. Z. J. Fam. Ther. 2020, 41, 231–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, B.L. Focused single-session psychotherapy: A review of the clinical work and research literature. Brief Treat. Crisis Interv. 2001, 1, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).