Bridging the Gap Between Climate and Health Systems: The Value of Resilience in Facing Extreme Weather Events

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Exploratory Literature Research

2.2. Country Selection

2.3. Policy Document Analysis

3. Results

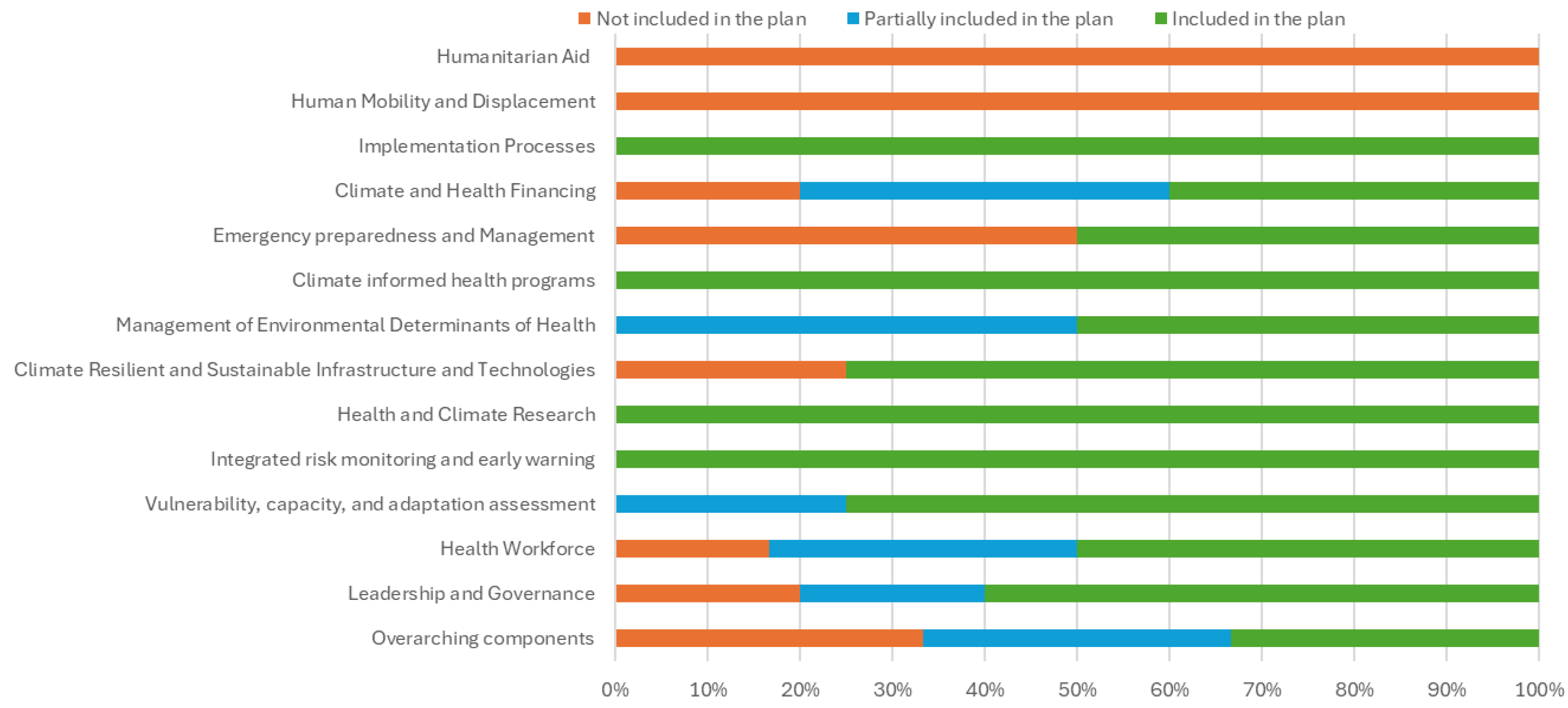

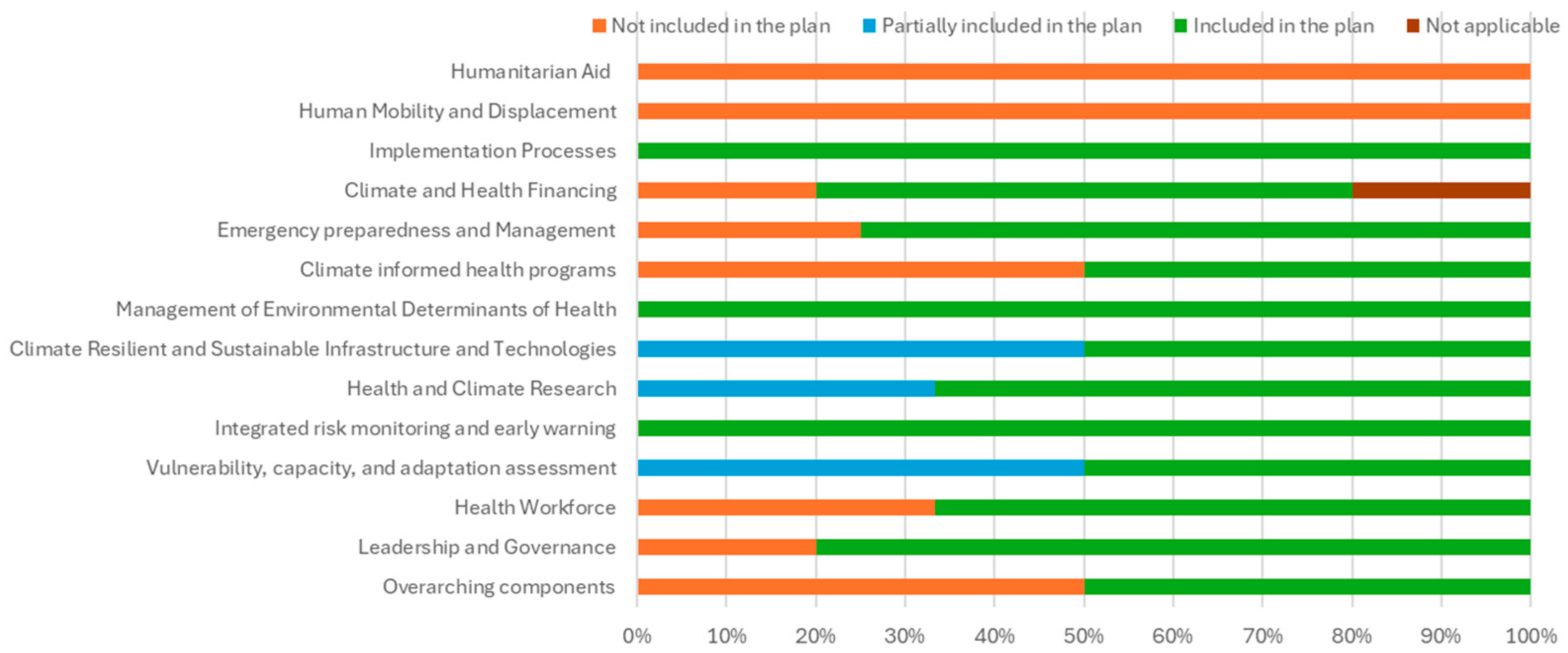

- Fiji fully addressed 30 questions, gave insufficient responses to 9 (20%), and failed to respond to 5 (11%)—a 68% full alignment rate.

- Tanzania fully addressed 32 questions, with 5 insufficient (11%) and 6 unanswered (14%)—a 73% full alignment rate.

- Fiji fully addressed one question (14%), gave an insufficient response to one (14%), and did not address five (71%).

- Tanzania fully addressed two questions (29%) and did not respond to five (71%).

4. Discussion

4.1. Leadership and Governance

4.2. Health Workforce

4.3. Climate-Resilient and Sustainable Infrastructure

4.4. Management of Environmental Determinants

4.5. Climate Health Financing

4.6. Missing Components of the WHO Operational Framework

4.6.1. Human Mobility and Displacement

4.6.2. Humanitarian Aid

4.6.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HSs | Health systems |

| EWEs | Extreme weather events |

| CC | Climate change |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| HCW | Healthcare workers |

| HISs | Health information systems |

| HNAP | Health National Adaptation Plan |

| NAP | National Adaptation Plan |

| CCA | Climate change adaptation |

| DRM | Disaster risk management |

| GHG | Greenhouse gas |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| HIA | Health impact assessments |

Appendix A. List of Analysis Questions

References

- Mpandeli, S.; Naidoo, D.; Mabhaudhi, T.; Nhemachena, C.; Nhamo, L.; Liphadzi, S.; Hlahla, S.; Modi, A.T. Climate Change Adaptation through the Water-Energy-Food Nexus in Southern Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costello, A.; Maslin, M.; Montgomery, H.; Johnson, A.M.; Ekins, P. Global Health and Climate Change: Moving from Denial and Catastrophic Fatalism to Positive Action. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2011, 369, 1866–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, N. EU Commission Takes Stand Against Danish Asylum Law. Available online: https://euobserver.com/migration/152193 (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Ebi, K.L.; Vanos, J.; Baldwin, J.W.; Bell, J.E.; Hondula, D.M.; Errett, N.A.; Hayes, K.; Reid, C.E.; Saha, S.; Spector, J.; et al. Extreme Weather and Climate Change: Population Health and Health System Implications. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2021, 42, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, K.J.; Ebi, K.L. Health Risks of Climate Change in the World Health Organization South-East Asia Region. WHO South-East Asia J. Public Health 2017, 6, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, Q.; Augusto, O.; Chicumbe, S.; Anselmi, L.; Wagenaar, B.H.; Marlene, R.; Agostinho, S.; Gimbel, S.; Pfeiffer, J.; Inguane, C.; et al. Maternal and Child Health Care Service Disruptions and Recovery in Mozambique After Cyclone Idai: An Uncontrolled Interrupted Time Series Analysis. Glob. Health Sci. Pract. 2022, 10, e2100796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization, International Institute for Sustainable Development. Health in National Adaptation Plans: Review; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; ISBN 9789240023604. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, I. Rich-Country Health Care Systems: Global Lessons; Devpolicy Blog: Canberra, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Codjoe, S.N.A.; Gough, K.V.; Wilby, R.L.; Kasei, R.; Yankson, P.W.K.; Amankwaa, E.F.; Abarike, M.A.; Atiglo, D.Y.; Kayaga, S.; Mensah, P.; et al. Impact of Extreme Weather Conditions on Healthcare Provision in Urban Ghana. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 258, 113072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddle, L.; Wahedi, K.; Bozorgmehr, K. Health System Resilience: A Literature Review of Empirical Research. Health Policy Plan. 2020, 35, 1084–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Operational Framework for Building Climate Resilient Health Systems; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; ISBN 978-92-4-156507-3. [Google Scholar]

- Kutzin, J.; Sparkes, S.P. Health Systems Strengthening, Universal Health Coverage, Health Security and Resilience. Bull. World Health Organ. 2016, 94, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rameshshanker, V.; Wyngaarden, S.; Lau, L.L.; Dodd, W. Health System Resilience to Extreme Weather Events in Asia-Pacific: A Scoping Review. Clim. Dev. 2021, 13, 944–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikomeye, J.C.; Rublee, C.S.; Beyer, K.M.M. Positive Externalities of Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation for Human Health: A Review and Conceptual Framework for Public Health Research. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjellstrom, T.; McMichael, A.J. Climate Change Threats to Population Health and Well-Being: The Imperative of Protective Solutions That Will Last. Glob. Health Action 2013, 6, 20816, Erratum in Glob. Health Action 2013, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbazza, E.; Tello, J.E. A Review of Health Governance: Definitions, Dimensions and Tools to Govern. Health Policy 2014, 116, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchet, K.; Nam, S.L.; Ramalingam, B.; Pozo-Martin, F. Governance and Capacity to Manage Resilience of Health Systems: Towards a New Conceptual Framework. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2017, 6, 431–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, A.; Karlstrom, J.; Ameha, A.; Oulare, M.; Omer, M.D.; Desta, H.H.; Bahuguna, S.; Hsu, K.; Miller, N.P.; Bati, G.T.; et al. The Contribution of Community Health Systems to Resilience: Case Study of the Response to the Drought in Ethiopia. J. Glob. Health 2022, 12, 14001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Safe, Climate-Resilient and Environmentally Sustainable Health Care Facilities: An Overview; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hanefeld, J.; Mayhew, S.; Legido-Quigley, H.; Martineau, F.; Karanikolos, M.; Blanchet, K.; Liverani, M.; Yei Mokuwa, E.; McKay, G.; Balabanova, D. Towards an Understanding of Resilience: Responding to Health Systems Shocks. Health Policy Plan. 2018, 33, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovats, S. (Ed.) Health Climate Change Impacts Summary Report Card. In Living Environ. Change; UK Research and Innovation: London, UK, 2015; pp. 1–20. ISBN 978-0-9928679-8-0. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, S.; Fair, A.; Wistow, J.; Val, D.V.; Oven, K. Impact of Extreme Weather Events and Climate Change for Health and Social Care Systems. Environ. Health 2017, 16, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landeg, O.; Whitman, G.; Walker-Springett, K.; Butler, C.; Bone, A.; Kovats, S. Coastal Flooding and Frontline Health Care Services: Challenges for Flood Risk Resilience in the English Health Care System. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2019, 24, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panic, M.; Ford, J. A Review of National-Level Adaptation Planning with Regards to the Risks Posed by Climate Change on Infectious Diseases in 14 OECD Nations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2013, 10, 7083–7109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mücke, H.-G.; Litvinovitch, J.M. Heat Extremes, Public Health Impacts, and Adaptation Policy in Germany. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebi, K.L.; Harris, F.; Sioen, G.B.; Wannous, C.; Anyamba, A.; Bi, P.; Boeckmann, M.; Bowen, K.; Cissé, G.; Dasgupta, P.; et al. Transdisciplinary Research Priorities for Human and Planetary Health in the Context of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CARE. CARE’s Resilience Marker. In CARE Climate Change; Cooperative for American Relief Everywhere: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dagneau, E.; Ehgartner, S.M. Bridging the Gap Between Climate and Health: The Value of Resilience in Facing Extreme Weather Events. Master’s Thesis, Syddansk Universitet SDU, Esbjerg, Denmark, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- WHO Global Health Expenditure Database. Available online: https://apps.who.int/nha/database/Select/Indicators/en (accessed on 24 May 2023).

- McMichael, A.J. The Urban Environment and Health in a World of Increasing Globalization: Issues for Developing Countries. Bull. World Health Organ. 2000, 78, 1117–1126. [Google Scholar]

- Nayna Schwerdtle, P.; Irvine, E.; Brockington, S.; Devine, C.; Guevara, M.; Bowen, K.J. ‘Calibrating to Scale: A Framework for Humanitarian Health Organizations to Anticipate, Prevent, Prepare for and Manage Climate-Related Health Risks’. Glob. Health 2020, 16, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of the Republic of Fiji. Republic of Fiji Natiopnal Adaptation Plan: A Pathway Towards Climate Resilience; Government of the Republic of Fiji: Suva, Republic of Fiji, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- United Republic of Tanzania, Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children. Health—National Adaptation Plan (HNAP) to Climate Change in Tanzania 2018–2023; United Republic of Tanzania, Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children: Dodoma, Tanzania, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ebi, K.L. Public Health Responses to the Risks of Climate Variability and Change in the United States. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2009, 51, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.; Dhamija, S.; Patil, J.; Chaudhari, B. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Healthcare Workers. Ind. Psychiatry J. 2021, 30, S282–S284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bignami, D.F. Disaster Risk Assessment, Reduction and Resilience: Their Reciprocal Contribution with Urban Planning to Advance Sustainability. In Green Planning for Cities and Communities; Dall’O’, G., Ed.; Research for Development; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 67–94. ISBN 978-3-030-41071-1. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). The Real Wealth of Nations: Pathways to Human Development; UNDP, Ed.; Human development report; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2010; ISBN 978-0-230-28445-6. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, J. Renolith Business Case. 2023. v1.7. pp. 1–20. Available online: https://renolith.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/2023-10-27-Renolith-2.0-Business-Case-v1.7.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Rahman, A.; Mwanundu, S.; Cooke, R. Climate Change: Building the Resilience of Poor Rural Communities; IFAD: Rome, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hime, N.; Vyas, A.; Lachireddy, K.; Wyett, S.; Scalley, B.; Corvalan, C. Climate Change, Health and Wellbeing: Challenges and Opportunities in NSW, Australia. Public Health Res. Pract. 2018, 28, e2841824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soete, L.; Albrecht, J.; Callaert, J.; Benczur, P.; Elfie, B.; Hobza, A.; Veugelers, R. Conference on R&D, Innovation, Sustainability, and the Societal Impact of New Technologies; BELSPO: Brussels, Belgium, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Wherton, J.; Papoutsi, C.; Lynch, J.; Hughes, G.; A’Court, C.; Hinder, S.; Fahy, N.; Procter, R.; Shaw, S. Beyond Adoption: A New Framework for Theorizing and Evaluating Nonadoption, Abandonment, and Challenges to the Scale-Up, Spread, and Sustainability of Health and Care Technologies. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017, 19, e367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akenji, L.; Bengtsson, M. Enabling Sustainable Lifestyles in a Climate Emergency; United Nations Environment Programme, Hot or Cool Institute: Berlin, Germany, 2022; pp. 1–14. ISBN 978-92-807-3938-1. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health and Medical Services. Climate Change and Health Strategic Action Plan 2016–2020: Building Climate-Resilient Health System in Fiji; Ministry of Health and Medical Services: New Delhi, India, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- The Congo Research Group (CRG). Ebola in the DRC: The Perverse Effects of a Parallel Health System; NYU Center on International Cooperation: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, Asia Pacific Regional Office. Health and Care for Migrants and Displaced Persons—Case Studies from the Asia Pacific Region; International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, Asia Pacific Regional Office: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Findlater, A.; Bogoch, I.I. Human Mobility and the Global Spread of Infectious Diseases: A Focus on Air Travel. Trends Parasitol. 2018, 34, 772–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMichael, C. Human Mobility, Climate Change, and Health: Unpacking the Connections. Lancet Planet. Health 2020, 4, e217–e218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IOM Migration, Environment and Climate Change (MECC) Division. Climate Change Impacts on Health Affecting Development and Human Mobility; IOM Migration, Environment and Climate Change (MECC) Division: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, E.T. On the Coloniality of Global Public Health. Med. Anthr. Theory 2019, 6, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruk, M.E.; Ling, E.J.; Bitton, A.; Cammett, M.; Cavanaugh, K.; Chopra, M.; El-Jardali, F.; Macauley, R.J.; Muraguri, M.K.; Konuma, S.; et al. Building Resilient Health Systems: A Proposal for a Resilience Index. BMJ 2017, 357, j2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, S.; Berry, H.L.; Ebi, K.; Bambrick, H.; Hu, W.; Green, D.; Hanna, E.; Wang, Z.; Butler, C.D. Climate Change, Food, Water and Population Health in China. Bull. World Health Organ. 2016, 94, 759–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| All Components for an Updated WHO-Framework | Questions from the WHO-Framework | Added Questions for the Guide | |

|---|---|---|---|

| WHO-Framework Components | Overarching components | 5 | 1 |

| 1. Component of Leadership and Governance | 3 | 2 | |

| 2. Component of Health Workforce | 5 | 1 | |

| 3. Component of Vulnerability, capacity, and adaptation assessment | 4 | 0 | |

| 4. Component of Integrated risk monitoring and early warning | 3 | 0 | |

| 5. Component of Health and Climate Research | 3 | 0 | |

| 6. Component of Climate Resilient and Sustainable Infrastructure and Technologies | 4 | 0 | |

| 7. Component of Management of Environmental Determinants of Health | 4 | 0 | |

| 8. Component of Climate informed health programs | 4 | 0 | |

| 9. Component of Emergency preparedness and Management | 4 | 0 | |

| 10. Component of Climate and Health Financing | 5 | 0 | |

| New | Component of Implementation Processes | 0 | 1 |

| Component of Human Mobility and Displacement | 0 | 1 | |

| Component of Humanitarian Aid | 0 | 1 | |

| Total | 44 | 7 |

| Total | Country 1 (Fiji) | Country 2 (Tanzania) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| + | +− | − | + | +− | − | N.A | ||

| Questions answered (n (% of total)) | 51 | 31 (61%) | 10 (20%) | 10 (20%) | 34 (67%) | 5 (10%) | 11 (22%) | 1 (2%) |

| WHO questions (% of total) | 44 (86%) | 30 (68%) | 9 (20%) | 5 (11%) | 32 (73%) | 5 (11%) | 6 (14%) | 1 (2%) |

| Questions based on additional literature sources (n (% of total questions)) | 7 (14%) | 1 (14%) | 1 (14%) | 5 (71%) | 2 (29%) | 0 | 5 (71%) | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dagneau, E.; Ehgartner, S.M.; Gulis, G. Bridging the Gap Between Climate and Health Systems: The Value of Resilience in Facing Extreme Weather Events. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1258. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081258

Dagneau E, Ehgartner SM, Gulis G. Bridging the Gap Between Climate and Health Systems: The Value of Resilience in Facing Extreme Weather Events. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(8):1258. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081258

Chicago/Turabian StyleDagneau, Eloïse, Sophie Marie Ehgartner, and Gabriel Gulis. 2025. "Bridging the Gap Between Climate and Health Systems: The Value of Resilience in Facing Extreme Weather Events" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 8: 1258. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081258

APA StyleDagneau, E., Ehgartner, S. M., & Gulis, G. (2025). Bridging the Gap Between Climate and Health Systems: The Value of Resilience in Facing Extreme Weather Events. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(8), 1258. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081258