Effectiveness of Technology-Based Interventions in Promoting Lung Cancer Screening Uptake and Decision-Making Among Patients

Abstract

1. Introduction

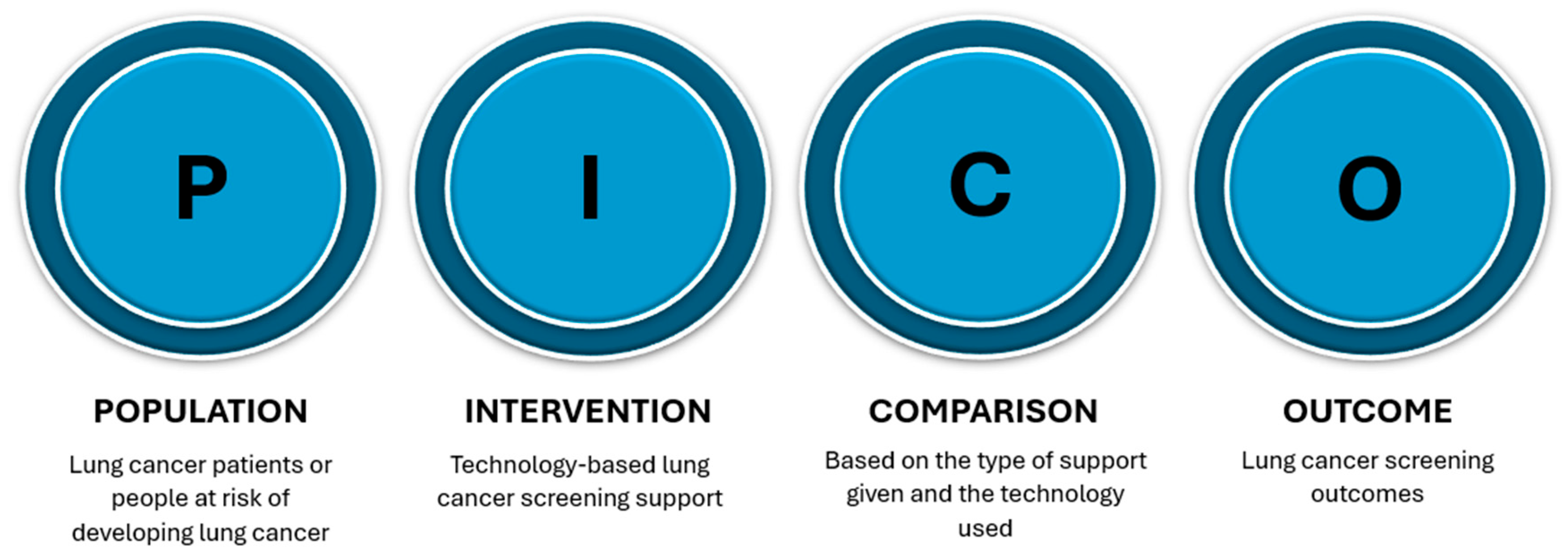

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

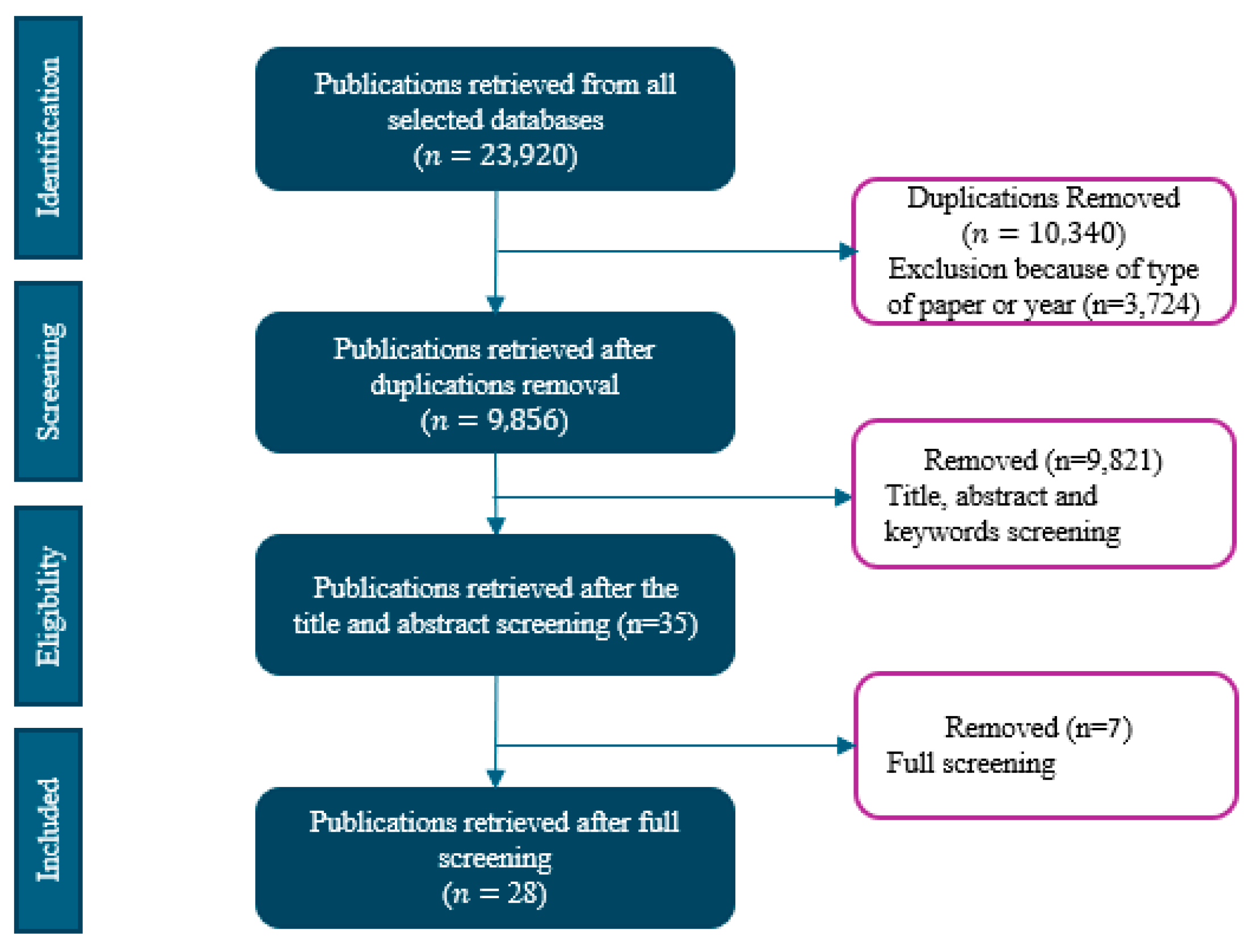

2.3. Screening and Selection Process

2.4. Quality Assessment and Risk of Bias

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

3.2. The Technology-Based Tools Developed to Support Lung Cancer Screening Promotion

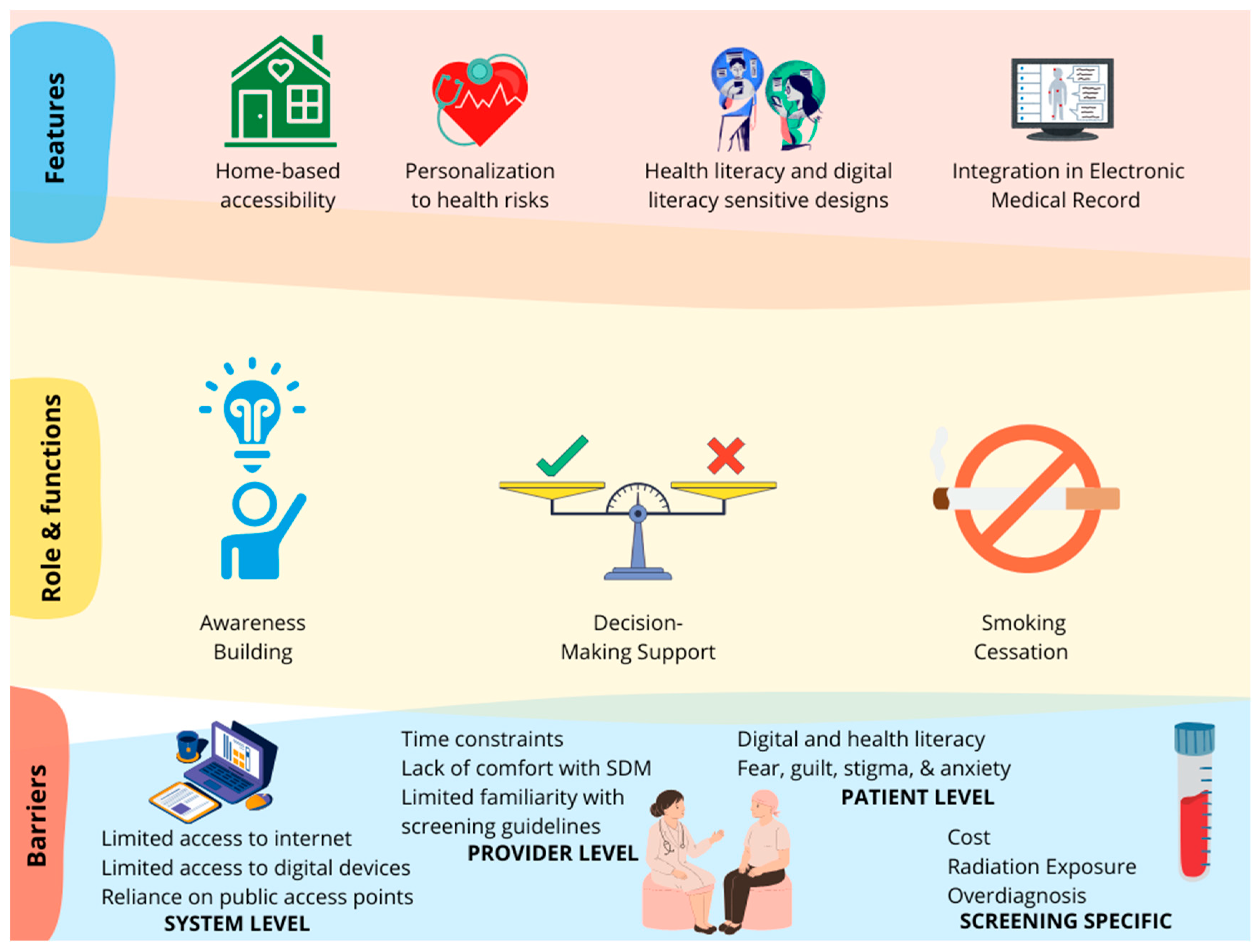

3.2.1. Features of Technology

3.2.2. Role of Technology in Supporting Lung Cancer Screening

Awareness Building and Education

Decision Support

Smoking Cessation

3.2.3. Barriers in Technology-Based Lung Cancer Screening Promotion

System-Level Barriers

Provider-Level Barriers

Patient-Level Barriers

Screening-Specific Barriers

4. Discussion

4.1. Potential of Technology in Promoting Lung Cancer Screening

4.1.1. Important Features for Consideration in Tool and Intervention Design

4.1.2. Role of Technology in Screening Promotion

Awareness and Education

Decision Support

Smoking Cessation Integration

4.2. Barriers to Technology-Based Lung Cancer Screening Promotion

4.2.1. System Level

4.2.2. Provider Level

4.2.3. Patient Level

4.2.4. Screening-Specific

4.3. Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. List of Keywords Used

| Medical Informatics-Related Keywords | Lung Cancer Keywords | Screening and Treatment-Related Keywords |

|---|---|---|

| Ehealth OR Informatics OR technology OR “Information Technology” OR “Electronic Health Records” OR Software OR Telemedicine OR informatics OR “information technologies” OR groupware OR “group ware” OR “computer supported cooperative work” OR “computer-supported cooperative work” OR “shared workspace” OR “shared work-space” OR “shared work space” OR “information and communication technology” OR “information and communication technology” OR “information and communication technologies” OR “information and communication technologies” OR “information systems” OR “information system” OR “data system” OR “data systems” OR “informational system” OR “computer system” OR “computer systems” OR “web-based” OR “internet-based” OR “web 2.0” OR “world wideweb” OR “world-wide web” OR “user-computer” OR “humancomputer” OR “computer interface” OR “computer interfaces” OR “health information exchange” OR “health information exchanges” OR “interoperability” OR “interoperable” OR “electronic health record” OR “electronic health records” OR “electronic medical record” OR “electronic medical records” OR “electronic patient record” OR “electronic patient records” OR “patient portal” OR “patient portals” OR “personal health record” OR “personal health records” OR “personal-health record” OR “personal-health records” OR “tethered health record” OR “tethered health records” ORmhealth OR “m-health” OR “mobile health” OR “touch screen” OR touchscreen OR “smart phone” OR ehealth OR “e-health” OR “electronic health” OR “electronic intervention” OR “digital intervention” OR “electronic tool” OR “digital tool” OR “digital technology” OR “electronic technology” OR “digital technologies” OR “digital health” OR “electronic technologies” OR “e-communication” OR “eintervention” OR telecounseling OR telemonitoring OR telemedicine OR “video visit” OR “video consult” OR “video consultation” OR telehealth OR “remotemonitoring” OR “internet communication technologies” OR “internet communication tool” OR “clinical decision support” OR teleconsultation OR teleconsultations. | “Lung Cancer” OR “lung-cancer” OR “Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer” OR NSCLC OR “Small Cell Lung Cancer” OR SCLC OR “Pulmonary Neoplasms” OR “Lung Neoplasms” OR “Lung Carcinoma” | Treatment OR Therapy OR Chemotherapy OR Radiotherapy OR Targeted Therapy OR Immunotherapy OR “Adjuvant Therapy” OR “Palliative Care” |

Appendix B. Data Extraction Form

| Variable | Description |

|---|---|

| ID | |

| Title | Title of article |

| Year | Year of publication |

| Objective | Objective of the study |

| Study design | Observational studies; cross-sectional studies; cohort studies (prospective and retrospective); case–control studies; ecological studies (exposure and outcomes studies); descriptive studies; experimental studies; randomized controlled trials (RCT); quasi-experimental studies; community trials; qualitative studies; mixed-methods studies |

| Intervention | Brief description of the intervention described in the study |

| Who is delivering the intervention | Researchers; healthcare providers; counselors |

| Setting | Home-based; clinic-based; or both |

| Recruitment methods | Clinic-based; online-based; in-person |

| Length of interventions | How many minutes/days/months the intervention lasts |

| Frequency of interventions | One time; number of days/months/years |

| Country/Region | Geographical location of study |

| Is it designed for rural/urban/ both populations/ not specified | Rural; urban; both; not specified |

| Smoking composition of the population (if reported) | Percentage of current smokers; percentage of former smokers; percentage of non-smokers |

| Challenges of screening addressed | Challenges of lung cancer screening addressed in the article |

| Type of technology | The mode of technology through which the intervention was delivered (e.g., website, video, EHR message) |

| Purpose of technology | Awareness building; decision-making support; risk assessment; appointment scheduling; education or behavior change intervention; other |

| Features of technology | Personalization (e.g., tailored reminders, recommendations); Interactivity level (e.g., static vs. dynamic content, gamification, interactive modules, AI-driven recommendations); accessibility (e.g., languages offered, availability for low-literacy users); integration with healthcare systems (e.g., EHR compatibility) |

| Does the tool provide smoking cessation counseling | Yes/No |

| Commercial tool/designed specifically for the study | Was the tool designed to be used in commercial settings or was the intervention designed specifically for the study? |

| Does the intervention (tool) consider any health and digital literacy | Yes/No. Was the intervention developed to a specific reading level? Were there other features that helped users comprehend the text in addition to the text itself? |

| For personal use or assisted use | Is the tool designed to be used with an assist from a family member/provider/other, or is the tool designed to be used independently? |

| Impact of technology on screening outcomes | Number of people screened after technology-based intervention (compared to number of people screened in control/before intervention) |

| Challenges of technology use | Challenges of technology described in the articles (e.g., computer/smartphone/internet access, font size, privacy concerns) |

| Challenge theme (to cluster later) | |

| Outcomes (measures) | Screening uptake (e.g., percentage of participants completing screenings); decision-making quality (e.g., decisional conflict, patient satisfaction, informed decision-making scores); awareness levels (e.g., change in knowledge, misconceptions corrected, understanding of risk factors); behavioral changes (e.g., smoking cessation, adherence to follow-up care, LCS uptake, engagement in decision-making, etc.); health outcomes (e.g., early-stage cancer detection rates, reduction in advanced cancer diagnoses, mortality rate, etc.); engagement metrics (e.g., frequency of technology use, completion rates of modules); patient empowerment (e.g., perceived control, self-efficacy) |

| Outcomes (findings) | Quantified data that support outcome measures |

| Study limitations | Limitations of the study described by the article |

| What was the technology compared to | Paper-based materials; standard education materials; other web-based interventions |

| What were the findings compared to the traditional or other modes of interventions | How did the technology-based intervention compare to the control? |

| What were the barriers to implementation | BARRIERS: Technical barriers (e.g., device limitations, connectivity issues); patient-level barriers (e.g., digital literacy, cultural stigma); system and environmental barriers (e.g., impact of friends on decision-making) FACILITATORS: Stakeholder involvement (e.g., healthcare providers, community outreach); training or education provided to patients |

| Community and cultural relevance of the technology | Technology tailored to specific cultural needs; inclusion of underserved populations (e.g., low-income, rural communities) |

Appendix C. Table of Findings

| ID | Title | Year | Objective | Study Design | Intervention | Delivery Personnel | Setting | Recruitment Methods | Length of Interventions | Intervention Frequency | Country/Region | Designed for Rural/Urban/both Populations | Smoking Composition of the Population | Challenges of Screening Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [22] | Evaluation of a Personalized, Web-Based Decision Aid for Lung Cancer Screening | 2015 | Assess the efficacy of a web-based patient decision aid for lung cancer screening | Uncontrolled, before-and-after study | Web-based decision aid | Research staff | Home-based | Convenience sample of volunteers (N = 60) | ~10 min | One time | United States | Not specified | Mean 24.08 pack-year smoking history; N = 60 current or former smokers | Follow-up diagnostic testing; overdiagnosis; false positive rate; total radiation exposure |

| [23] | Feasibility of a Patient Decision Aid about Lung Cancer Screening with Low-dose Computed Tomography | 2014 | Development and testing of a brief, video-based patient decision aid about lung cancer screening | Uncontrolled, before-and-after design | Video-based patient decision aid | Research staff | Clinic-based | Patients from a tobacco treatment program at a large cancer center | 6 min video | One time | United States | Not specified | Mean 30 pack-year smoking history; N = 23 (44.2%) current smokers, N = 29 (55.8%) former smokers | Radiation exposure; high false-positive rate with invasive testing a follow-up; overtreatment of nonfatal cancers; psychological harms (anxiety, depression); real or perceived financial strain |

| [24] | A pre–post study testing a lung cancer screening decision aid in primary care | 2018 | Testing of a lung cancer screening decision aid video in screening-eligible primary care patients | Single-group (screening-eligible), before-and-after study | Video decision aid | Research staff | Clinic-based—academic internal medicine practice | Mail and online; primary providers approved list of patients; patients mailed recruitment packet (study invitation letter, opt-out card); patients received recruitment phone call (eligibility survey); participants received a USD 40 gift card | 6 min video | One time | United States | Not specified | Mean 52 pack-year smoking history; 46% current smokers (avg 52 pack-years smoked), 54% former smokers | Costly and invasive follow-up; overdiagnosis; lack of LCS knowledge |

| [25] | Population health nurse-driven lung cancer screening | 2024 | Pilot of a patient-centered population health nurse-driven LCS intervention in a general internal medicine practice embedded in an urban safety-net health system | Pilot study | Telemedicine visit with population health nurse | Research staff | Home-based | Phone-based patients with the greatest number of overdue screenings are contacted and scheduled for a telehealth visit where the nurse performs lung cancer screening opportunities | Not specified | One time | United States | Not specified | N = 237 patients with current or previous smoking history | Competing priorities in the medical visit; lack of documentation of robust smoking histories; absence of clinical decision support for primary care teams; patient and provider knowledge gaps; access to screening |

| [26] | “I Saw it Incidentally but Frequently”: Exploring the Effects of Online Health Information Scanning on Lung Cancer Screening Behaviors Among Chinese Smokers | 2024 | Investigate whether online health information scanning can effectively encourage lung cancer screening and elucidate the mechanisms driving this association among smokers | Random-sample survey | Online health information - News apps on smartphones - Health-related apps on smartphones - Social media - Search engines | Research staff | Home-based | Online from Kantar’s survey panel | Not specified | Variable health information seeking measured frequency participants searched for health information | China | Not specified | N = 992 individuals who have cumulatively smoked 100 cigarettes and have reported cigarette use in the last 30 days | Not specified |

| [27] | The tobacco quitline setting as a teachable moment: The Educating Quitline Users About Lung (EQUAL) cancer screening randomized trial | 2023 | Assess if state-based tobacco quitlines serve as a teachable moment for LCS-eligible individuals | Randomized control trial | Web-based decision tool | Research staff | Home-based | Individuals seeking phone-based cessation treatment from the Maryland Tobacco Quitline | ~15 min | One time | United States | Not specified | Mean 60.3 pack-year smoking history; 70.1% currently smoking | Time (too busy, not enough time); low priority (concurrent health issues); logistics (transportation issues); worry (worried about cost, worry that screening will find something wrong, worried the scan will be dangerous); knowledge and attitudes (do not feel they need to be screened, not aware of LCS, want to quit smoking first); health system barriers (no insurance or PCP, PCP never brought it up) |

| [29] | A veteran-centric web-based decision aid for lung cancer screening: usability analysis | 2022 | Conduct usability testing of an LCSDecTool designed for veterans receiving care at a Veteran Affairs medical center | Usability testing | Computer-based | Research staff | Both settings | Online-based (to identify) Corporate Data Warehouse was used to identify eligible veterans; eligible participants were mailed recruitment letters | 13 min (median) | One time | United States | Not specified | At least 30 pack-year smoking history; eligible veterans had a 30 pack-year hx of smoking and continued smoking within the past 15 years | False positive tests; significant incidental findings; overdiagnosis |

| [28] | Development of an electronic health record self-referral tool for lung cancer screening: one-group post-test study | 2023 | Develop and pilot an electronic health record (EHR) patient-facing self-referral tool to an established LCS program in an academic medical center | One-group post-test study | EHR-delivered engagement message, infographic, and self-referring survey | Research staff | Home-based | Online-based; MRNs identified from another ongoing quality improvement study in the MUSC LCS program | Not specified | One time | United States | Not specified | At least 20 pack-year smoking history; N = 6 (35.2%) current smokers, N = 11 (64.7%) former smokers | Provider level: lack of familiarity with eligibility criteria; insufficient time or knowledge to conduct shared decision-making; skepticism about the benefits of screening; familiarity with managing screen-detected findings Patient level: need for more awareness of screening eligibility or programs; cost concerns; insurance status; challenges in accessing imaging sites; LCS (first preventative screening to target poor health behavior) patients are less likely to have PCP or engage in screening services |

| [30] | The reach and feasibility of an interactive lung cancer screening decision aid delivered by patient portal | 2019 | Health systems could adopt population-level approaches to screening by identifying potential screening candidates from the electronic health records and reaching out to them via the patient portal. However, whether patients would read or act on sent information is unknown. We examined the feasibility of this digital health outreach strategy | Single-arm pragmatic trial | Web- and tablet-based interactive website | Research staff | Both settings | EHR algorithm identified candidates scheduled to see PCP within 4 weeks and had logged into their patient portal account within the last 90 days; patients were sent a message via the patient portal with a hyperlink containing a unique study ID | 9.6 h (median time between reading the portal message and visiting the app) | One time | United States | Not specified | At least 30 pack-year smoking history; N = 186 (19%) current smokers, N = 811 (81%) former smokers | False-positive test results leading to invasive procedures and complications; scheduling; care access limitations; complexities of varying risk and benefits of screening by individual risk factors |

| [31] | Using a smoking cessation quitline to promote lung cancer screening | 2018 | Assessing whether in-depth messaging delivered via a smoking cessation quit-line results in participants: (1) speaking to their physician or (2) an insurance company regarding lung cancer screening | Randomized trial | Phone-based messaging following brochure | Research staff | Home-based | New York State Smokers Quitline; eligible participants - current smokers - 55–79 - smoking hx of at least 30 pack-years - agreed to be contacted for a 4-month follow-up - English speaking | Telephone call | One time | United States | Not specified | Mean 45 pack-year smoking history | Low awareness of guidelines |

| [32] | Improving utilization of lung cancer screening through incorporating a video-based educational tool into smoking cessation counseling | 2020 | Investigation of the effect of LCS educational information on LDCT utilization and smoking cessation in LCS-eligible patients receiving smoking cessation counseling through video-based education | Randomized control trial | Web-based educational video | Research staff | Home-based | Online-based; individuals who currently smoke who attended at least 1 smoking cessation counseling cessation at KPSC | Less than 30 min video | One time | United States | Not specified | At least 30 pack-year smoking history; N = 584 (56.9%) currently smoking, N = 442 (43.1%) previous smokers | Limited information; majority of smoking cessation services offer no education on LDCT; limited knowledge of potential benefits of LDCT |

| [33] | Effect of a patient decision aid on lung cancer screening decision-making by persons who smoke | 2019 | Examine the effect of a patient decision aid about lung cancer screening compared with a standard educational material (EDU) on decision-making outcomes among smokers | Randomized clinical trial | Video-based: “Lung Cancer Screening: Is It Right for Me?” | Research staff | Home-based | Tobacco quitline clients from 13 states - 55–77 - 30-plus pack-year smoking hx - English speaking | 9.5 min narrated video | One time | United States | Not specified | Mean 48 pack-year smoking history; N = 516 (quitline patients) current or previous smokers | Radiation exposure from screening and diagnostic imaging; high false-positive rate leading to subsequent testing |

| [34] | Impact of a lung cancer screening counseling and shared decision-making visit | 2017 | Assist patients with the decision about participation in screening through a shared decision-making visit with narrated slide show | Single-arm trial | Narrated video slide show | Research staff | Clinic-based | Clinic-based; online-based PCPs identified potentially eligible patients and screening program reviewed patient’s EMR to confirm they met screening program eligibility criteria | 6 min narrated video slide show | One time | United States | Not specified | Mean 53 pack-year smoking history; out of 423 total patients, 45.2% were active smokers | Minority of patients will experience benefits of LCS; all have the potential to be harmed |

| [35] | Using social media as a platform for increasing Knowledge of lung cancer screening in high-risk patients | 2020 | Explore and assess education of and motivation to discuss lung cancer screening with healthcare providers after viewing educational materials on social media | Pre-experimental, one-group pre-test and post-test design | Video-based | Research staff | Home-based | Online-based advertisement generated through Facebook | 6 min video | One time | United States | Not specified | At least 30 pack-year smoking history; N = 11 (35.5%) current smokers, N = 20 (64.5%) former smokers | Lack of patient-provider discussions about LCS; uncertainty and low motivation; lack of knowledge about LCS; fatalistic beliefs; fear of radiation exposure; anxiety related to CT scans |

| [36] | Lung cancer screening Knowledge, perceptions, and decision making among African Americans in Detroit, Michigan | 2021 | Evaluate a previously developed web-based patient-facing decision aid for lung cancer screening among African Americans in Metro Detroit | Before-and-after study | Web-based, patient decision aid | Research staff | Home-based | In-person recruitment at community events on the east side of Detroit | 5–10 min | One time | United States | Urban | 25% of participants reported 30 pack-year smoking history; N = 51 (68.9%) current smokers, N = 23 (31.1%) former smokers | Lower education |

| [37] | Aiding shared decision making in lung cancer screening: two decision tools | 2020 | Compare two SDM decision aids (Option Grids and Shouldiscreen.com) for shared decision-making, efficacy, decision regret, and knowledge | Randomized control trial | Web-based: two websites (www.optiongrid.org and www.shouldiscreen.com) | Research staff | Home-based | Referred by physicians | Not specified | One time | United States | Urban | At least 30 pack-year smoking history; N = 240 (all patients) had a current or previous smoking hx of at least 30 pack-years | Potential harms; false positive results; complications as a result of positive screens; overdiagnosis; radiation exposure |

| [38] | Randomized electronic promotion of lung cancer screening: A pilot | 2017 | Determine the feasibility of LCS promotion and estimate the size of the population of former smokers who are eligible for LCS screening in a single health care system | Pilot study (randomized control trial?) where participants were randomly assigned to intervention and control group | EHR-portal-based electronic messages to promote LCS | Research staff | Home-based | EHR-identified patients from University of Minnesota pulmonary clinics or primary care clinics within the past 2 years | Not specified | One time | United States | Not specified | At least 30 pack-year smoking history; N = 200 former smokers randomly allocated, N = 652 assessed for eligibility | Not specified |

| [39] | Implementation of an electronic clinical reminder to improve rates of lung cancers screening | 2014 | Implement electronic clinical reminder to improve the uptake of lung cancer screening in appropriate high-risk patients | Retrospective cohort study | EHR-delivered clinical reminders | Research staff | Home-based | EHR-based (retrospective cohort study) | Not specified | One time | United States | Not specified | N = 2372 (39.9%) met screening criteria of being a current smoker or quitting within the past 15 years and had smoked more than 30 pack-years | Not specified |

| [40] | A Patient Decision Aid to Help Heavy Smokers Make Decisions about Lung Cancer Screening | 2019 | Compare decision-making outcomes about LCS among patients recruited through state-based tobacco quitlines, where patients were randomly assigned to the decision aid or to standard educational materials about LCS | Randomized controlled trial | Video decision aid | Research staff | Home-based | Referred from smoking quitline in different states | 6 min video | One time | United States | Not specified | Mean 54.6 pack-year smoking history (intervention); 55.6 (control), average 43.4 years in intervention, 43.8 years in control | Misunderstanding and concerns; lack of awareness of screening; low preparedness for decision-making |

| [41] | Lung Cancer Screening Decision Aid Designed for a Primary Care Setting: A Randomized Clinical Trial | 2023 | Evaluate the impact on an LCS decision tool on the quality of decision-making and LCS uptake | Randomized controlled trial | Web-based patient- and clinical-facing LCS decision support tool | Research staff | Home-based | Identified LCS-eligible veterans from VA Medical centers in Pennsylvania, Connecticut, and Wisconsin | 1.4 min for intervention group 5.2 min for control group | One time | United States | Not specified | Mean 40.5 pack-year smoking history (intervention), 45.0 (control); current smokers: 73.9% in intervention, 57.7% in control | False-positive results; overdiagnosis; radiation exposure |

| [43] | Impact of a Lung Cancer Screening Information Film on Informed Decision-making: A Randomized Trial | 2019 | Evaluate the impact of a novel information film on informed decision-making in individuals considering participating in LCS | Randomized controlled trial | Information film, booklet, short counseling with hcp | Health care providers (nurses, clinical trial staff) | Home-based | Identified from primary care records or participants of the lung screen uptake trial | 10 min video | One time | United Kingdom | Not specified | Mean 38 pack-year smoking history (intervention), 35 control; median for cigarette smoking: intervention—16 cigarettes/day, control—15 cigarettes/day; number of pack-years, median: intervention 38, control 35; year smoked, median: intervention 47, control 46 | High information burden that discourages people with low literacy from taking part in LCS |

| [42] | Computer-Tailored Decision Support Tool for Lung Cancer Screening: Community-Based Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial | 2020 | Estimate the effects of a computer-tailored decision support tool that meets the certification criteria of the international Patient Decision Aid Standards that will prepare individuals and support shared decision-making in lung cancer screening decisions | Randomized controlled trial | LungTalk Interactive Program (computer-tailored decision support tool) | Research staff | Home-based | Facebook targeting advertisement | 20 min baseline survey; intervention length not specified | One time | United States | Not specified | Mean 48.7 pack-year smoking history; year smoked, 36.6; former smokers, 46.7%; current smokers, 53.3% | Low level of knowledge and awareness for lung cancer screening |

| [44] | Telephone-Based Shared Decision-making for Lung Cancer Screening in Primary Care | 2020 | Examine the feasibility of application of a telephone-based decision support tool via an online tool for promoting lung cancer screening | Feasibility study | Decision Counseling Program© (DCP) online with telephone-based call with counselor | Trained decision counselor | Home-based | Identified from electronic medical record data and recruited from calls | 10–15 min baseline survey; total intervention length not specified | One time | United States | Not specified | Mean 46.54 pack-year smoking history (total), 55.0 (screened), 42.97 (not screened); current smokers, 67.9%; former smokers, 32.1% | How to effectively promote lung cancer screening rate; poor shared decision-making in clinical setting |

| [45] | What is the effect of a decision aid on Knowledge, values and preferences for lung cancer screening? An online pre–post study | 2021 | Examine whether a decision aid improves knowledge of lung cancer screening benefits and harms and which benefits and harms are most valued | Observational studies | Web-based lung cancer screening video decision aid | Not specified | Home-based | Online participant panel | 3.5 min video | One time | United States | Not specified | Mean 47.2 pack-year smoking history (current smokers), 63.1 (former smokers); mean pack-year smoking for current smokers, 47.2, and mean pack-year smoking for former smokers, 63.1 | Low level of knowledge for lung cancer screening |

| [46] | Development and testing of “Is Lung Cancer Screening for You?” A computer-based decision aid | 2023 | Investigate the feasibility, acceptability, usability, and preliminary effectiveness of a computer-based decision aid | Observational studies | Decision aid for lung cancer screening on RedCap | Research Staff | Clinic-based | Recruited from upcoming patients, emailing, and flyer distribution | 5.95 min | One time | United States | Not specified | All current or former smokers (N = 33) | Providers have limited time and capacity to engage in shared decision-making for LCS; lack of knowledge about risk; fear; reservation because of stigma associated with lung cancer |

| [47] | Using a Patient Decision Aid Video to Assess Current and Former Smokers’ Values About the Harms and Benefits of Lung Cancer Screening With Low-Dose Computed Tomography | 2018 | Explore how current and former smokers value potential benefits and harms after watching a patient decision aid | Observational studies | Decision aid video: Lung Cancer Screening: Is It Right for Me? | Not specified | Home-based | Recruited from the tobacco treatment program at MD Anderson Center | Not specified | One time | United States | Not specified | Mean 30.4 pack-year smoking history | Low level of knowledge and awareness of LCS |

| [48] | Primary care outreach and decision counseling for lung cancer screening | 2024 | Determine the effect of an SDM intervention on lung cancer screening in primary care | Single-arm clinical trial | Decision Counseling Program, an online software that facilitate shared decision-making | Trained decision counselor | Home-based | Identified through electronic health records and recruited by mail and phone calls | 10–15 min | One time | United States | Not specified | Mean 45.6 pack-year smoking history | Lack of effective methods to facilitate and integrate SDM; low lung cancer screening uptake; time pressure during primary care visits |

| [49] | Lung Cancer Screening Before and After a Multifaceted Electronic Health Record Intervention: A Nonrandomized Controlled Trial | 2024 | Assess the association of a multifaceted clinical decision support intervention with rates of identification and completion of recommended LCS-related services | Controlled interrupted time series | An EHR-integrated shared decision-making tool and narrative guidance and clinician/patient-facing reminders | Research staff | Both settings (Phase 1, clinical-based Phase 2) | Identified through electronic healthcare records | Period of 1–11 months; period of 2–9 months | Provided at each visit | United States | Not specified | Median time smoked 40 years, cigarettes per day 20, current smoker: baseline—49.8%, period 1—51.6%, period 2 51.4%. | Low LCS uptake; methods of screening other than chest CT remain unexplored |

References

- World Health Organization. Global Cancer Burden Growing, Amidst Mounting Need for Services. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/01-02-2024-global-cancer-burden-growing--amidst-mounting-need-for-services?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- World Cancer Research Fund. Lung Cancer Statistics. Available online: https://www.wcrf.org/preventing-cancer/cancer-statistics/lung-cancer-statistics/#:~:text=Lung%20cancer%20deaths-,Latest%20lung%20cancer%20data,and%20mortality%20from%20lung%20cancer (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Amicizia, D.; Piazza, M.F.; Marchini, F.; Astengo, M.; Grammatico, F.; Battaglini, A.; Schenone, I.; Sticchi, C.; Lavieri, R.; Di Silverio, B.; et al. Systematic Review of Lung Cancer Screening: Advancements and Strategies for Implementation. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Screening for Lung Cancer. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/lung-cancer/screening/index.html (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Overman, D. Lung Cancer Screening Dramatically Increases Long-Term Survival Rate. AXIS Imaging News 2022. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/3c2fe22ec34418b3c3deeb1e0072770d/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=2037571 (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Henschke, C.I.; Yip, R.; Shaham, D.; Markowitz, S.; Cervera Deval, J.; Zulueta, J.J.; Seijo, L.M.; Aylesworth, C.; Klingler, K.; Andaz, S. A 20-year follow-up of the international early lung cancer action program (I-ELCAP). Radiology 2023, 309, e231988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokaj, R. Early CT Lung Cancer Screening Significantly Improves Survival in Lung Cancer. Available online: https://www.cancernetwork.com/view/early-ct-lung-cancer-screening-significantly-improves-survival-in-lung-cancer (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- World Health Organization. Lung Cancer. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/lung-cancer?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Wang, G.X.; Baggett, T.P.; Pandharipande, P.V.; Park, E.R.; Percac-Lima, S.; Shepard, J.-A.O.; Fintelmann, F.J.; Flores, E.J. Barriers to lung cancer screening engagement from the patient and provider perspective. Radiology 2019, 290, 278–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernstein, E.; Bade, B.C.; Akgün, K.M.; Rose, M.G.; Cain, H.C. Barriers and facilitators to lung cancer screening and follow-up. Semin. Oncol. 2022, 49, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-A.; Hong, Y.T.; Lin, X.J.; Lin, J.L.; Xiao, H.M.; Huang, F.F. Barriers and facilitators to uptake of lung cancer screening: A mixed methods systematic review. Lung Cancer 2022, 172, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejezie, C.L.; Sacca, L.; Ayieko, S.; Burgoa, S.; Zerrouki, Y.; Lobaina, D.; Okwaraji, G.; Markham, C. Use of Digital Health Interventions for Cancer Prevention Among People Living With Disabilities in the United States: A Scoping Review. Cancer Med. 2025, 14, e70571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, D. Computer-based approaches to patient education: A review of the literature. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 1999, 6, 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percac-Lima, S.; Ashburner, J.M.; Zai, A.H.; Chang, Y.; Oo, S.A.; Guimaraes, E.; Atlas, S.J. Patient navigation for comprehensive cancer screening in high-risk patients using a population-based health information technology system: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 2016, 176, 930–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gysels, M.; Higginson, I.J. Interactive technologies and videotapes for patient education in cancer care: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. Support. Care Cancer 2007, 15, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krist, A.H.; Woolf, S.H.; Hochheimer, C.; Sabo, R.T.; Kashiri, P.; Jones, R.M.; Lafata, J.E.; Etz, R.S.; Tu, S.-P. Harnessing information technology to inform patients facing routine decisions: Cancer screening as a test case. Ann. Fam. Med. 2017, 15, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, J.; Ng, A.; Wong, G.J.; Siew, K.Y.; Tan, J.K.; Pang, Y.; Tan, K.-K. How effective are digital technology-based interventions at promoting colorectal cancer screening uptake in average-risk populations? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Prev. Med. 2022, 164, 107343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirsch, E.P.; Kunte, S.A.; Wu, K.A.; Kaplan, S.; Hwang, E.S.; Plichta, J.K.; Lad, S.P. Digital health platforms for breast cancer care: A scoping review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, R.I.; Niendorf, K.; Petzel, S.; Lee, H.; Teoh, D.; Blaes, A.H.; Argenta, P.; Rivard, C.; Winterhoff, B.; Lee, H.Y.; et al. A patient-centered mobile health application to motivate use of genetic counseling among women with ovarian cancer: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Gynecol. Oncol. 2019, 153, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravitt, P.E.; Coutlée, F.; Iftner, T.; Sellors, J.W.; Quint, W.G.; Wheeler, C.M. New technologies in cervical cancer screening. Vaccine 2008, 26, K42–K52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruco, A.; Dossa, F.; Tinmouth, J.; Llovet, D.; Jacobson, J.; Kishibe, T.; Baxter, N. Social media and mHealth technology for cancer screening: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e26759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, Y.K.; Caverly, T.J.; Cao, P.; Cherng, S.T.; West, M.; Gaber, C.; Arenberg, D.; Meza, R. Evaluation of a Personalized, Web-Based Decision Aid for Lung Cancer Screening. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2015, 49, e125–e129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volk, R.J.; Linder, S.K.; Leal, V.B.; Rabius, V.; Cinciripini, P.M.; Kamath, G.R.; Munden, R.F.; Bevers, T.B. Feasibility of a patient decision aid about lung cancer screening with low-dose computed tomography. Prev. Med. 2014, 62, 60–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reuland, D.S.; Cubillos, L.; Brenner, A.T.; Harris, R.P.; Minish, B.; Pignone, M.P. A pre-post study testing a lung cancer screening decision aid in primary care. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2018, 18, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansen, E.; Bolivar, J.; Auguste, S.; Clancy, M.; Kearney, L.; Henderson, L.; Steiling, K.; Cordella, N. Population Health Nurse-Driven Lung Cancer Screening. NEJM Catal. Innov. Care Deliv. 2024, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Ye, J.F.; Zhao, X. “I Saw it Incidentally but Frequently”: Exploring the Effects of Online Health Information Scanning on Lung Cancer Screening Behaviors Among Chinese Smokers. Health Commun. 2025, 40, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, M.; Whealan, J.; Williams, R.M.; Eyestone, E.; Le, A.; Childs, J.; Kao, J.Y.; Martin, M.; Wolfe, S.; Yang, F.; et al. The tobacco quitline setting as a teachable moment: The Educating Quitline Users About Lung (EQUAL) cancer screening randomized trial. Transl. Behav. Med. 2023, 13, 736–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stang, G.S.; Tanner, N.T.; Hatch, A.; Godbolt, J.; A Toll, B.; Rojewski, A.M. Development of an Electronic Health Record Self-Referral Tool for Lung Cancer Screening: One-Group Posttest Study. JMIR Form. Res. 2024, 8, e53159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schapira, M.M.; Chhatre, S.; Prigge, J.M.; Meline, J.; Kaminstein, D.; Rodriguez, K.L.; Fraenkel, L.; Kravetz, J.D.; Whittle, J.; Bastian, L.A.; et al. A Veteran-Centric Web-Based Decision Aid for Lung Cancer Screening: Usability Analysis. JMIR Form. Res. 2022, 6, e29039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharod, A.; Bellinger, C.; Foley, K.; Case, L.D.; Miller, D. The Reach and Feasibility of an Interactive Lung Cancer Screening Decision Aid Delivered by Patient Portal. Appl. Clin. Inform. 2019, 10, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Bansal-Travers, M.; Celestino, P.; Fine, J.; Reid, M.E.; Hyland, A.; O’Connor, R. Using a Smoking Cessation Quitline to Promote Lung Cancer Screening. Am. J. Health Behav. 2018, 42, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raz, D.J.; Ismail, M.H.; Haupt, E.C.; Sun, V.; Park, S.; Alem, A.C.; Gould, M.K. Improving Utilization of Lung Cancer Screening Through Incorporating a Video-Based Educational Tool Into Smoking Cessation Counseling. Clin. Lung Cancer 2021, 22, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volk, R.J.; Lowenstein, L.M.; Leal, V.B.; Escoto, K.H.; Cantor, S.B.; Munden, R.F.; Rabius, V.A.; Bailey, L.; Cinciripini, P.M.; Lin, H.; et al. Effect of a Patient Decision Aid on Lung Cancer Screening Decision-Making by Persons Who Smoke: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e1920362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzone, P.J.; Tenenbaum, A.; Seeley, M.; Petersen, H.; Lyon, C.; Han, X.; Wang, X.F. Impact of a Lung Cancer Screening Counseling and Shared Decision-Making Visit. Chest 2017, 151, 572–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strong, A.; Renaud, M. Using Social Media as a Platform for Increasing Knowledge of Lung Cancer Screening in High-Risk Patients. J. Adv. Pract. Oncol. 2020, 11, 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, Y.K.; Bhattarai, H.; Caverly, T.J.; Hung, P.Y.; Jimenez-Mendoza, E.; Patel, M.R.; Cote, M.L.; Arenberg, D.A.; Meza, R. Lung Cancer Screening Knowledge, Perceptions, and Decision Making Among African Americans in Detroit, Michigan. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2021, 60, e1–e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sferra, S.R.; Cheng, J.S.; Boynton, Z.; DiSesa, V.; Kaiser, L.R.; Ma, G.X.; Erkmen, C.P. Aiding shared decision making in lung cancer screening: Two decision tools. J. Public Health 2021, 43, 673–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begnaud, A.L.; Joseph, A.M.; Lindgren, B.R. Randomized Electronic Promotion of Lung Cancer Screening: A Pilot. JCO Clin. Cancer Inform. 2017, 1, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federman, D.G.; Kravetz, J.D.; Lerz, K.A.; Akgun, K.M.; Ruser, C.; Cain, H.; Anderson, E.F.; Taylor, C. Implementation of an electronic clinical reminder to improve rates of lung cancer screening. Am. J. Med. 2014, 127, 813–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volk, R.J.A.; Lowenstein, L.M.; Escoto, K.H.; Cantor, S.B.; Munden, R.F.; Rabius, V.A.; Bailey, L.; Cinciripini, P.M.; Lin, H.; Leal, V.B.; et al. A Patient Decision Aid to Help Heavy Smokers Make Decisions about Lung Cancer Screening. Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI): Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schapira, M.M.; Hubbard, R.A.; Whittle, J.; Vachani, A.; Kaminstein, D.; Chhatre, S.; Rodriguez, K.L.; Bastian, L.A.; Kravetz, J.D.; Asan, O.; et al. Lung Cancer Screening Decision Aid Designed for a Primary Care Setting: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2330452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter-Harris, L.; Comer, R.S.; Slaven Ii, J.E.; Monahan, P.O.; Vode, E.; Hanna, N.H.; Ceppa, D.P.; Rawl, S.M. Computer-Tailored Decision Support Tool for Lung Cancer Screening: Community-Based Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e17050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruparel, M.; Quaife, S.L.; Ghimire, B.; Dickson, J.L.; Bhowmik, A.; Navani, N.; Baldwin, D.R.; Duffy, S.; Waller, J.; Janes, S.M. Impact of a Lung Cancer Screening Information Film on Informed Decision-making: A Randomized Trial. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2019, 16, 744–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagan, H.B.; Fournakis, N.A.; Jurkovitz, C.; Petrich, A.M.; Zhang, Z.; Katurakes, N.; Myers, R.E. Telephone-Based Shared Decision-making for Lung Cancer Screening in Primary Care. J. Cancer Educ. 2020, 35, 766–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, S.D.; Reuland, D.S.; Brenner, A.T.; Pignone, M.P. What is the effect of a decision aid on knowledge, values and preferences for lung cancer screening? An online pre-post study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e045160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, O.L.; McDonnell, K.K.; Newsome, B.R.; Humphrey, M. Development and testing of “Is Lung Cancer Screening for You?” A computer-based decision aid. Cancer Causes Control 2023, 34, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, A.S.; Hempstead, A.P.; Housten, A.J.; Richards, V.F.; Lowenstein, L.M.; Leal, V.B.; Volk, R.J. Using a Patient Decision Aid Video to Assess Current and Former Smokers’ Values About the Harms and Benefits of Lung Cancer Screening With Low-Dose Computed Tomography. MDM Policy Pract. 2018, 3, 2381468318769886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagan, H.B.; Jurkovitz, C.; Zhang, Z.; Thompson, L.A.; Patterson, F.; Zazzarino, M.A.; Myers, R.E. Primary care outreach and decision counseling for lung cancer screening. J. Med. Screen. 2024, 31, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukhareva, P.V.; Li, H.; Caverly, T.J.; Fagerlin, A.; Del Fiol, G.; Hess, R.; Zhang, Y.; Butler, J.M.; Schlechter, C.; Flynn, M.C.; et al. Lung Cancer Screening Before and After a Multifaceted Electronic Health Record Intervention: A Nonrandomized Controlled Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2415383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prochaska, J.J.; Coughlin, S.S.; Lyons, E.J. Social media and mobile technology for cancer prevention and treatment. In American Society of Clinical Oncology Educational Book; Meeting; American Society of Clinical Oncology: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2017; p. 128. [Google Scholar]

- Noordman, J.; Noordam, D.; van Treeck, J.; Prantl, K.; Pennings, P.; Borsje, P.; Heinen, M.; Emond, Y.; Rake, E.; Boland, G. Visual decision aids to support communication and shared decision-making: How are they valued and used in practice? PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0314732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alslaity, A.; Chan, G.; Orji, R. A panoramic view of personalization based on individual differences in persuasive and behavior change interventions. Front. Artif. Intell. 2023, 6, 1125191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brawer, R.; Pham, K. Using health literacy principles to engage patients from diverse backgrounds in lung cancer screening. In Lung Cancer Screening: A Population Approach; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 211–226. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R. Examining the Impact of Design Features of Electronic Health Records Patient Portals on the Usability and Information Communication for Shared Decision Making. 2022. Available online: https://open.clemson.edu/all_dissertations/3050/ (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Simmons, V.N.; Gray, J.E.; Schabath, M.B.; Wilson, L.E.; Quinn, G.P. High-risk community and primary care providers knowledge about and barriers to low-dose computed topography lung cancer screening. Lung Cancer 2017, 106, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Screening for Lung Cancer with Low Dose Computed Tomography (LDCT). Available online: https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/view/ncacal-decision-memo.aspx?proposed=N&NCAId=274&bc=AAAAAAAAAgAAAA (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Baptista, S.; Teles Sampaio, E.; Heleno, B.; Azevedo, L.F.; Martins, C. Web-based versus usual care and other formats of decision aids to support prostate cancer screening decisions: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018, 20, e228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, M.P.; Barker, M. Why is changing health-related behaviour so difficult? Public Health 2016, 136, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stacey, D.; Légaré, F.; Lewis, K.; Barry, M.J.; Bennett, C.L.; Eden, K.B.; Holmes-Rovner, M.; Llewellyn-Thomas, H.; Lyddiatt, A.; Thomson, R. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 2017, CD001431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Weert, J.C.; Van Munster, B.C.; Sanders, R.; Spijker, R.; Hooft, L.; Jansen, J. Decision aids to help older people make health decisions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2016, 16, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riikonen, J.M.; Guyatt, G.H.; Kilpeläinen, T.P.; Craigie, S.; Agarwal, A.; Agoritsas, T.; Couban, R.; Dahm, P.; Järvinen, P.; Montori, V. Decision aids for prostate cancer screening choice: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern. Med. 2019, 179, 1072–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krist, A.H.; Beasley, J.W.; Crosson, J.C.; Kibbe, D.C.; Klinkman, M.S.; Lehmann, C.U.; Fox, C.H.; Mitchell, J.M.; Mold, J.W.; Pace, W.D. Electronic health record functionality needed to better support primary care. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2014, 21, 764–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McBride, C.M.; Emmons, K.M.; Lipkus, I.M. Understanding the potential of teachable moments: The case of smoking cessation. Health Educ. Res. 2003, 18, 156–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigotti, N.A.; Munafo, M.R.; Stead, L.F. Smoking cessation interventions for hospitalized smokers: A systematic review. Arch. Intern. Med. 2008, 168, 1950–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamin, C.K.; Emani, S.; Williams, D.H.; Lipsitz, S.R.; Karson, A.S.; Wald, J.S.; Bates, D.W. The digital divide in adoption and use of a personal health record. Arch. Intern. Med. 2011, 171, 568–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeliadt, S.B.; Hoffman, R.M.; Birkby, G.; Eberth, J.M.; Brenner, A.T.; Reuland, D.S.; Flocke, S.A. Challenges implementing lung cancer screening in federally qualified health centers. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2018, 54, 568–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, U.; Karter, A.J.; Liu, J.Y.; Adler, N.E.; Nguyen, R.; Lopez, A.; Schillinger, D. The literacy divide: Health literacy and the use of an internet-based patient portal in an integrated health system—Results from the Diabetes Study of Northern California (DISTANCE). J. Health Commun. 2010, 15, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coughlin, S.S.; Stewart, J.L.; Young, L.; Heboyan, V.; De Leo, G. Health literacy and patient web portals. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2018, 113, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cataldo, J.K.; Jahan, T.M.; Pongquan, V.L. Lung cancer stigma, depression, and quality of life among ever and never smokers. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2012, 16, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzone, P.J.; Silvestri, G.A.; Patel, S.; Kanne, J.P.; Kinsinger, L.S.; Wiener, R.S.; Hoo, G.S.; Detterbeck, F.C. Screening for lung cancer: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest 2018, 153, 954–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.-C.; McFeeters, J. Out-of-pocket health spending between low-and higher-income populations: Who is at risk of having high expenses and high burdens? Med. Care 2006, 44, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Elkefi, S.; Gaillard, N.; Wu, R. Effectiveness of Technology-Based Interventions in Promoting Lung Cancer Screening Uptake and Decision-Making Among Patients. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1250. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081250

Elkefi S, Gaillard N, Wu R. Effectiveness of Technology-Based Interventions in Promoting Lung Cancer Screening Uptake and Decision-Making Among Patients. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(8):1250. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081250

Chicago/Turabian StyleElkefi, Safa, Nelson Gaillard, and Rongyi Wu. 2025. "Effectiveness of Technology-Based Interventions in Promoting Lung Cancer Screening Uptake and Decision-Making Among Patients" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 8: 1250. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081250

APA StyleElkefi, S., Gaillard, N., & Wu, R. (2025). Effectiveness of Technology-Based Interventions in Promoting Lung Cancer Screening Uptake and Decision-Making Among Patients. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(8), 1250. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081250