Can Dietary Supplements Be Linked to a Vegan Diet and Health Risk Modulation During Vegan Pregnancy, Infancy, and Early Childhood? The VedieS Study Protocol for an Explorative, Quantitative, Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

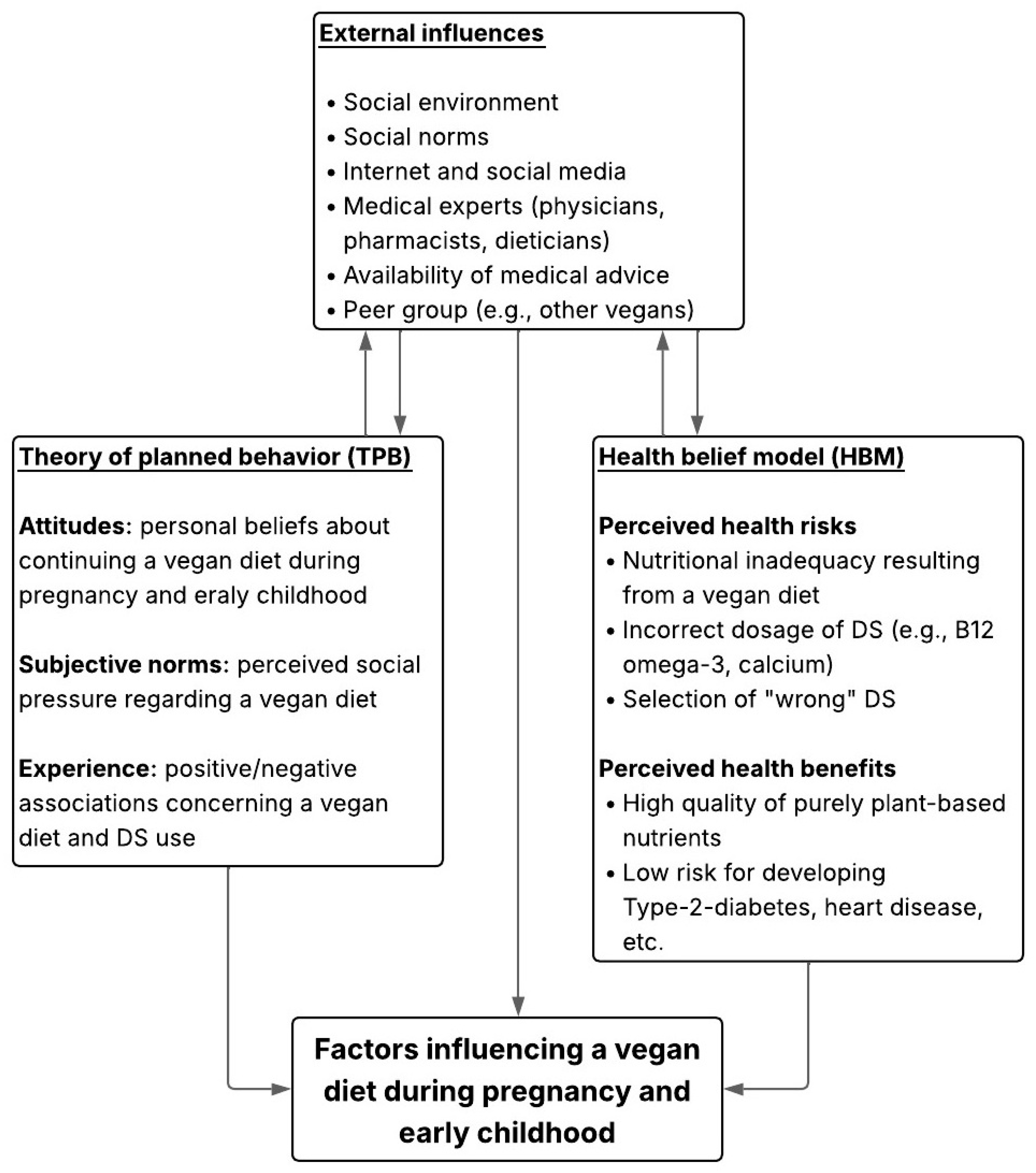

Theoretical Framework

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Objective

2.1.1. Primary Objectives

Determination of Main Influential Factors That Affect Vegans Regarding Their Diet During Pregnancy and When Feeding Their Children (Up to the Age of 5 Years)

Opinions and General Knowledge of Medical Experts About a Vegan Diet and Dietary Supplements (For a Vegan Pregnancy, Infancy and Early Childhood) Should Be Established

2.1.2. Secondary Objectives

Determination of the Level of Knowledge of Vegans on Dietary Supplements, Nutrient Deficiency Risks and Correct Dosage of Dietary Supplements During Pregnancy, Infancy and Early Childhood (Up to the Age of 5 Years)

Investigation of Conceptualization of Dietary Supplements, with a Special Focus on Their Contribution to Health Maintenance and Optimization from Vegans’ Perspective

Determination of Compliance with Dietary Supplements During Pregnancy, Infancy and Early Childhood as Well as the Consequences of Administration Difficulties to Vegan-Fed Children (Up to the Age of 5 Years)

Investigate if Gender-Specific and Socio-Demographic Differences Within the Group of Vegans Exist

- Illustrate the importance and necessity of comprehensive advice on DS from medical experts;

- Reduce the risk of malnutrition of vegans by encouraging physicians, pharmacists and dieticians to provide competent advice;

- Promote further training on the knowledge of a vegan diet and DS among medical experts;

- Increase the willingness to optimize the food and nutritional health literacy of pregnant vegans and parents of vegan-fed children and raise their awareness of its importance.

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Participants

2.4. Eligibility Criteria

- 1.

- Females/diverse participants (ages 18 and over) who follow/followed a vegan diet during their pregnancy/pregnancies (if there is/was more than one pregnancy, at least during one of their pregnancies).

- 2.

- Parents (female/male/diverse—ages 18 and over) who feed/fed their child/children (if there is more than one child, at least one of them) a vegan diet at least between the ages of 0 and 5 years.

- 3.

- Vegan mothers/diverse participants (ages 18 and over) who breastfeed/breastfed their infant(s)/child(ren). Answering questions regarding their infant(s)/child(ren) up to the age of 5 years will be included.

- 4.

- Pregnant and breastfeeding women/gender diverse participants/parents (f/m/d) who make rare exceptions to their vegan diet and a vegan diet of their child(ren)—up to the age of 5 years. Inclusion in the survey depends on the frequency of exceptions → determined through questions/given answers within the survey. Participants that consume animal products a maximum of twice a month will be included; hence, participants who do not make vegetarian, pescetarian, or omnivorous exceptions more than twice a month will be included.

- 5.

- Confirmation of the participant information (online—addressing the subjects, purpose and process of the study, opportunities for discussion of further questions, duration of the questionnaire, who is conducting the study, possibility for further inquiries).

- 1.

- Females/diverse participants who change/changed their vegan diet (eat/ate a vegetarian or omnivorous diet) during their pregnancy/pregnancies.

- 2.

- Parents who do not feed/have never fed their children a vegan diet at least up to the age of 5 years (if vegan mothers followed a vegan diet during their pregnancy, exclusion only relates to questions concerning their children).

- 3.

- No confirmation of the participant information (online).

- 1.

- Gynecologists, pediatricians, general practitioners, pharmacists, and dieticians with or without a consulting focus on vegans.

- 2.

- Confirmation of the participant information (online).

- 1.

- Other medical specialists not mentioned in the inclusion criteria.

- 2.

- No confirmation of the participant information.

2.5. Questionnaires

2.6. Calculations of Case Number Scenarios

2.6.1. Sample Size

Planned Sample Size for Vegan Participants

Planned Sample Size for Medical Experts

2.7. Statistical Methods and Data Analysis

- -

- People living in rural vs. urban areas;

- -

- Supplement users vs. non-users (for themselves or their children);

- -

- Participants who changed their diet during pregnancy vs. those who did not;

- -

- Individuals who received professional advice vs. those who used informal sources like social media.

- -

- Those who support vs. those who reject vegan diets during pregnancy and childhood;

- -

- Those who advise supplementation vs. those who discourage it;

- -

- Differences between professions (e.g., pediatricians, pharmacists, dietitians).

2.8. Trial Status

2.9. Data Security

3. Results/Outcome Measures

3.1. Primary Outcome Measures

3.2. Secondary Outcome Measures

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

5.1. Practical Implications

5.2. Limitations and Strengths of the Study

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DS | Dietary Supplements |

| PI | Principal Investigator |

| WHS | Wolfgang Huber-Schneider |

| KHW | Karl-Heinz Wagner |

| IK | Ingrid Kiefer |

| HBM | Health Belief Model |

| TPB | Theory of Planned Behavior |

| DHA | Docosahexaenoic acid |

| EPA | Eicosapentaenoic acid |

References

- Richter, M.; Boeing, H.; Grünewald-Funk, D.; Heseker, H.; Kroke, A.; Leschik-Bonnet, E.; Watzl, B. For the German Nutrition Society (DGE). Vegan diet. Position of the German Nutrition Society (DGE). Ernahr. Umsch. 2016, 63, 92–102. [Google Scholar]

- England, E.; Cheng, C. Nutrition: Micronutrients. FP Essent. 2024, 539, 13–17. [Google Scholar]

- Koeder, C. Toward Supplementation Guidelines for Vegan Complementary Feeding. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 12, 10962–10971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amit, M.C.P.S.; Canadian Paediatric Society; Community Paediatrics Committee. Vegetarian diets in children and adolescents. Paediatr. Child Health 2010, 15, 303–314. [Google Scholar]

- Palma, O.; Jallah, J.K.; Mahakalkar, M.G.; Mendhe, D.M. The Effects of Vegan Diet on Fetus and Maternal Health: A Review. Cureus 2023, 15, e47971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skoven, F.H.; Sejer, E.; Palm, C.V.; Thetmark, T.; Kristensen, A.; Marxen, S.; Jeppesen, M.M.; Hansen, H.; Olesen, R.; Beerman, T.; et al. Vegetarian and vegan diets among pregnant and breastfeeding women. Ugeskr. Laeger 2025, 187, V05240304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastiani, G.; Barbero, A.H.; Borràs-Novell, C.; Alsina, M.; Aldecoa-Bilbao, V.; Andreu-Fernández, V.; Tutusaus, M.P.; Martínez, S.F.; Gómez-Roig, M.D.; García-Algar, Ó. The effects of vegetarian and vegan diet during pregnancy on the health of mothers and offspring. Nutrients 2019, 11, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemale, J.; Mas, E.; Jung, C.; Bellaiche, M.; Tounian, P.; Hepatology, F.S.P. Vegan diet in children and adolescents. Recommendations from the French-speaking Pediatric Hepatology, Gastroenterology and Nutrition Group (GFHGNP). Arch. De Pédiatrie 2019, 26, 442–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, W.J.; Mangels, A.R. Position of the American Dietetic Association: Vegetarian Diets. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2009, 109, 1266–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leiva, T.S.; Muñoz, Y.; Aguirre, L.T.; Castillo, P.E. Vitamin B12, fatty acids EPA and DHA during pregnancy and lactation in women with a plant-based diet. Nutr. Hosp. 2024, 41, 1098–1104. [Google Scholar]

- Hedegaard, S.; Nohr, E.A.; Olsen, S.F.; Halldorsson, T.I.; Renault, K.M. Adherence to different forms of plant-based diets and pregnancy outcomes in the Danish National Birth Cohort: A prospective observational study. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2024, 103, 1046–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avnon, T.; Paz Dubinsky, E.; Lavie, I.; Ben-Mayor Bashi, T.; Anbar, R.; Yogev, Y. The impact of a vegan diet on pregnancy outcomes. J. Perinatol. 2021, 41, 1129–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgas, F.; Bitsch, L.; König, L.M.; Beitze, D.E.; Scherbaum, V.; Podszun, M.C. Dietary supplement use among lactating mothers following different dietary patterns–an online survey. Matern. Health Neonatol. Perinatol. 2024, 10, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gandino, S.; Bzikowska-Jura, A.; Karcz, K.; Cassidy, T.; Wesolowska, A.; KrólAk-Olejnik, B.; Klotz, D.; Arslanoglu, S.; Picaud, J.; Boquien, C.; et al. Vegan/vegetarian diet and human milk donation: An EMBA survey across European milk banks. Matern. Child Nutr. 2024, 20, e13564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ureta-Velasco, N.; Keller, K.; Escuder-Vieco, D.; Fontecha, J.; Calvo, M.V.; Megino-Tello, J.; Serrano, J.C.E.; Ferreiro, C.R.; García-Lara, N.R.; Pallás-Alonso, C.R. Human milk composition and nutritional status of omnivore human milk donors compared with vegetarian/vegan lactating mothers. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bali, A.; Naik, R. The impact of a vegan diet on many aspects of health: The overlooked side of veganism. Cureus 2023, 15, e35148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangels, R.; Driggers, J. The youngest vegetarians: Vegetarian infants and toddlers. ICAN Infant Child Adolesc. Nutr. 2012, 4, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Koebnick, C.; Gruendel, S.; Hoffmann, I.; Dagnelie, P.C.; Heins, U.A.; Wickramasinghe, S.N.; Ratnayaka, I.D.; Lindemans, J.; Leitzmann, C. Long-term ovo-lacto vegetarian diet impairs vitamin B-12 status in pregnant women. J. Nutr. 2004, 134, 3319–3326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlak, R.; Vos, P.; Shahab-Ferdows, S.; Hampel, D.; Allen, L.H.; Perrin, M.T. Vitamin B-12 content in breast milk of vegan, vegetarian, and nonvegetarian lactating women in the United States. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 108, 525–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlak, R. To vegan or not to vegan when pregnant, lactating or feeding young children. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 71, 1259–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melina, V.; Craig, W.; Levin, S. Position of the academy of nutrition and dietetics: Vegetarian diets. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2016, 116, 1970–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klug, A.; Richter, M.; Virmani, K.; Conrad, J.; Watzl, B.; Barbaresko, J.; Alexy, U.; Nöthlings, U.; Kühn, T.; Kroke, A.; et al. Update of the DGE position on vegan diet—Position statement of the German Nutrition Society (DGE). Ernahr. Umsch. 2024, 71, 60–84. [Google Scholar]

- The Austrian Nutrition Society. Available online: https://www.oege.at/category/ernaehrungsweise/faq-vegane-ernaehrung/ (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Meulenbroeks, D.; Otten, E.; Smeets, S.; Groeneveld, L.; Jonkers, D.; Eussen, S.; Scheepers, H.; Gubbels, J. The association of a vegan diet during pregnancy with maternal and child outcomes: A systematic review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccoli, G.B.; Clari, R.; Vigotti, F.N.; Leone, F.; Attini, R.; Cabiddu, G.; Mauro, G.; Castelluccia, N.; Colombi, N.; Capizzi, I.; et al. Vegan–vegetarian dietsin pregnancy: Danger or panacea? A systematic narrative review. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2015, 122, 623–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouraqui, J.P. Risk assessment of micronutrients deficiency in vegetarian or vegan children: Not so obvious. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, G.; Fadnes, L.T.; Meltzer, H.M.; Arnesen, E.K.; Henriksen, C. Follow-up of pregnant women, breastfeeding mothers and infants on a vegetarian or vegan diet. Tidsskr. Den Nor. Legeforening 2022, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simeone, G.; Bergamini, M.; Verga, M.C.; Cuomo, B.; D’antonio, G.; Iacono, I.D.; Di Mauro, D.; Di Mauro, F.; Di Mauro, G.; Leonardi, L.; et al. Do vegetarian diets provide adequate nutrient intake during complementary feeding? A systematic review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, J.M.; Comeau, M.E.; Smith, J.L.; Swanson, K.; Anderson, C.M. Vegetarian Diets During Pregnancy: With Supplementation, Ovo-Vegetarian, Lacto-Vegetarian, Vegan, and Pescatarian Adaptations of US Department of Agriculture Food Patterns Can Be Nutritionally Adequate. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2025, 125, 204–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiely, M.E. Risks and benefits of vegan and vegetarian diets in children. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2021, 80, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, B.; Wright, C. Safety and efficacy of supplements in pregnancy. Nutr. Rev. 2020, 78, 813–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malek, L.; Umberger, W.J.; Makrides, M.; Collins, C.T.; Zhou, S.J. Understanding motivations for dietary supplementation during pregnancy: A focus group study. Midwifery 2018, 57, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kostecka, M.; Kostecka, J.; Jackowska, I.; Iłowiecka, K. Parental Nutritional Knowledge and Type of Diet as the Key Factors Influencing the Safety of Vegetarian Diets for Children Aged 12–36 Months. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bivi, D.; Di Chio, T.; Geri, F.; Morganti, R.; Goggi, S.; Baroni, L.; Mumolo, M.G.; de Bortoli, N.; Peroni, D.G.; Marchi, S.; et al. Raising children on a vegan diet: Parents’ opinion on problems in everyday life. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villette, C.; Vasseur, P.; Lapidus, N.; Debin, M.; Hanslik, T.; Blanchon, T.; Steichen, O.; Rossignol, L. Vegetarian and Vegan Diets: Beliefs and Attitudes of General Practitioners and Pediatricians in France. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebinghaus, M.; Agricola, C.J.; Schmittinger, J.; Makarova, N.; Zyriax, B.C. Assessment of women’s needs, wishes and preferences regarding interprofessional guidance on nutrition in pregnancy—A qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2024, 24, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baroni, L.; Goggi, S.; Battaglino, R.; Berveglieri, M.; Fasan, I.; Filippin, D.; Griffith, P.; Rizzo, G.; Tomasini, C.; Tosatti, M.A.; et al. Vegan nutrition for mothers and children: Practical tools for healthcare providers. Nutrients 2018, 11, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rathmann, A.M.; Seifert, R. Vitamin A-containing dietary supplements from German and US online pharmacies: Market and risk assessment. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 2024, 397, 6803–6820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, E.; Parke, M.; Perez-Sanchez, A.; Zamil, D.; Katta, R. Acne supplements sold online. Dermatol. Pract. Concept. 2022, 12, e2022029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austrian Agency for Health and Food Safety GmbH. Available online: https://www.ages.at/ages/presse/news/detail/kontrollaktion-nahrungsergaenzungsmittel-aus-dem-internet (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Saldanha, L.G.; Dwyer, J.T.; Andrews, K.W.; Brown, L.L.; Costello, R.B.; Ershow, A.G.; Gusev, P.A.; Hardy, C.J.; Pehrsson, P.R. Is nutrient content and other label information for prescription prenatal supplements different from nonprescription products? J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2017, 117, 1429–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamil, D.H.; Burns, E.K.; Perez-Sanchez, A.; Parke, M.A.; Katta, R. Risk of birth defects from vitamin A “acne supplements” sold online. Dermatol. Pract. Concept. 2021, 11, e2021075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldassarre, M.E.; Panza, R.; Farella, I.; Posa, D.; Capozza, M.; Mauro, A.D.; Laforgia, N. Vegetarian and vegan weaning of the infant: How common and how evidence-based? A population-based survey and narrative review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koeder, C.; Perez-Cueto, F.J. Vegan nutrition: A preliminary guide for health professionals. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 670–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulou, T.; Sarantaki, A.; Metallinou, D.; Palaska, E.; Nanou, C.; Diamanti, A. Strict vegetarian diet and pregnancy outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Metab. Open 2024, 25, 100338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbier, M.; Boisseau, I.; Lemale, J.; Chevallier, M.; Mortamet, G. Medical management of vegetarian and vegan children in France: Medical practices and parents’ perceptions. Arch. Pediatr. 2024, 31, 136–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beressa, G.; Whiting, S.J.; Belachew, T. Effect of nutrition education integrating the health belief model and theory of planned behavior on dietary diversity of pregnant women in Southeast Ethiopia: A cluster randomized controlled trial. Nutr. J. 2024, 23, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riazi, S.; Ghavami, V.; Sobhani, S.R.; Shoorab, N.J.; Mirzakhani, K. The effect of nutrition education based on the Health Belief Model (HBM) on food intake in pregnant Afghan immigrant women: A semi-experimental study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2024, 24, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armitage, C.J.; Conner, M. Efficacy of the Theory of Planned Behaviour: A meta-analytic review. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 40, 471–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LimeSurvey. Available online: https://www.limesurvey.org/de/ (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Vegane Gesellschaft Österreich. Available online: https://www.vegan.at/zahlen (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Przybysz, P.; Kruszewski, A.; Kacperczyk-Bartnik, J.; Romejko-Wolniewicz, E. The Impact of Maternal Plant-Based Diet on Obstetric and Neonatal Outcomes—A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Austria—The Information Manager. Available online: https://www.statistik.at/en/statistics/population-and-society/population/births/demographic-characteristics-of-newborns (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Bardheci, K.; Jäger, L.; Risch, L.; Rosemann, T.; Burgstaller, J.M.; Markun, S. Testing and Prescribing Vitamin B12 in Swiss General Practice: A Survey among Physicians. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamiel, U.; Landau, N.; Fuhrer, A.E.; Shalem, T.; Goldman, M. The knowledge and attitudes of pediatricians in Israel towards vegetarianism. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2020, 71, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeitler, M.; Storz, M.A.; Steckhan, N.; Matthiae, D.; Dressler, J.; Hanslian, E.; Koppold, D.A.; Kandil, F.I.; Michalsen, A.; Kessler, C.S. Knowledge, attitudes and application of critical nutrient supplementation in vegan diets among healthcare professionals—Survey results from a medical congress on plant-based nutrition. Foods 2022, 11, 4033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farella, I.; Panza, R.; Baldassarre, M.E. The difficult alliance between vegan parents and pediatrician: A case report. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereboom, J.; Meulenbroeks, D.; Gerards, S.M.; Eussen, S.J.; Scheepers, H.C.; Jonkers, D.M.; Gubbels, J.S. Mothers adhering to a vegan diet: Feeding practices of their young children and underlying determinants—A qualitative exploration. J. Nutr. Sci. 2025, 14, e26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cnossen, M.C.; Tichelman, E.; Bostelaar, V.; van Dijk, S.; Hendrickx, C.; Welling, L. Veganism during pregnancy: Exploring experiences and needs of women following a plant-based diet. Sex. Reprod. Healthc. 2025, 44, 101094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLeod, S.C.; McCormack, J.C.; Oey, I.; Conner, T.S.; Peng, M. Knowledge, attitude and practices of health professionals with regard to plant-based diets in pregnancy: A scoping review. Public Health Nutr. 2024, 27, e170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meulenbroeks, D.; Jonkers, D.; Scheepers, H.; Gubbels, J. Obstetric healthcare experiences and information needs of Dutch women in relation to their vegan diet during pregnancy. Prev. Med. Rep. 2024, 48, 102916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuschlberger, M.; Putz, P. Vitamin B12 supplementation and health behavior of Austrian vegans: A cross-sectional online survey. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 3983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlak, R.; Parrott, S.J.; Raj, S.; Cullum-Dugan, D.; Lucus, D. How prevalent is vitamin B 12 deficiency among vegetarians? Nutr. Rev. 2013, 71, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huber-Schneider, W.; Wagner, K.-H.; Kiefer, I. Can Dietary Supplements Be Linked to a Vegan Diet and Health Risk Modulation During Vegan Pregnancy, Infancy, and Early Childhood? The VedieS Study Protocol for an Explorative, Quantitative, Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1210. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081210

Huber-Schneider W, Wagner K-H, Kiefer I. Can Dietary Supplements Be Linked to a Vegan Diet and Health Risk Modulation During Vegan Pregnancy, Infancy, and Early Childhood? The VedieS Study Protocol for an Explorative, Quantitative, Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(8):1210. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081210

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuber-Schneider, Wolfgang, Karl-Heinz Wagner, and Ingrid Kiefer. 2025. "Can Dietary Supplements Be Linked to a Vegan Diet and Health Risk Modulation During Vegan Pregnancy, Infancy, and Early Childhood? The VedieS Study Protocol for an Explorative, Quantitative, Cross-Sectional Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 8: 1210. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081210

APA StyleHuber-Schneider, W., Wagner, K.-H., & Kiefer, I. (2025). Can Dietary Supplements Be Linked to a Vegan Diet and Health Risk Modulation During Vegan Pregnancy, Infancy, and Early Childhood? The VedieS Study Protocol for an Explorative, Quantitative, Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(8), 1210. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081210