Cost-Effectiveness of Youth-Friendly Health Services in Health Post Settings in Jimma Zone, Ethiopia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.1.1. Decision Tree Model Structure

2.1.2. Epidemiological and Population Basis

2.2. Study Area, Area, and Population

Intervention Description

2.3. Data Collection and Sources

2.3.1. Costing Estimation

2.3.2. Health Outcome Measurement

2.3.3. Sensitivity Analysis

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Costing Breakdown of YFHS Services

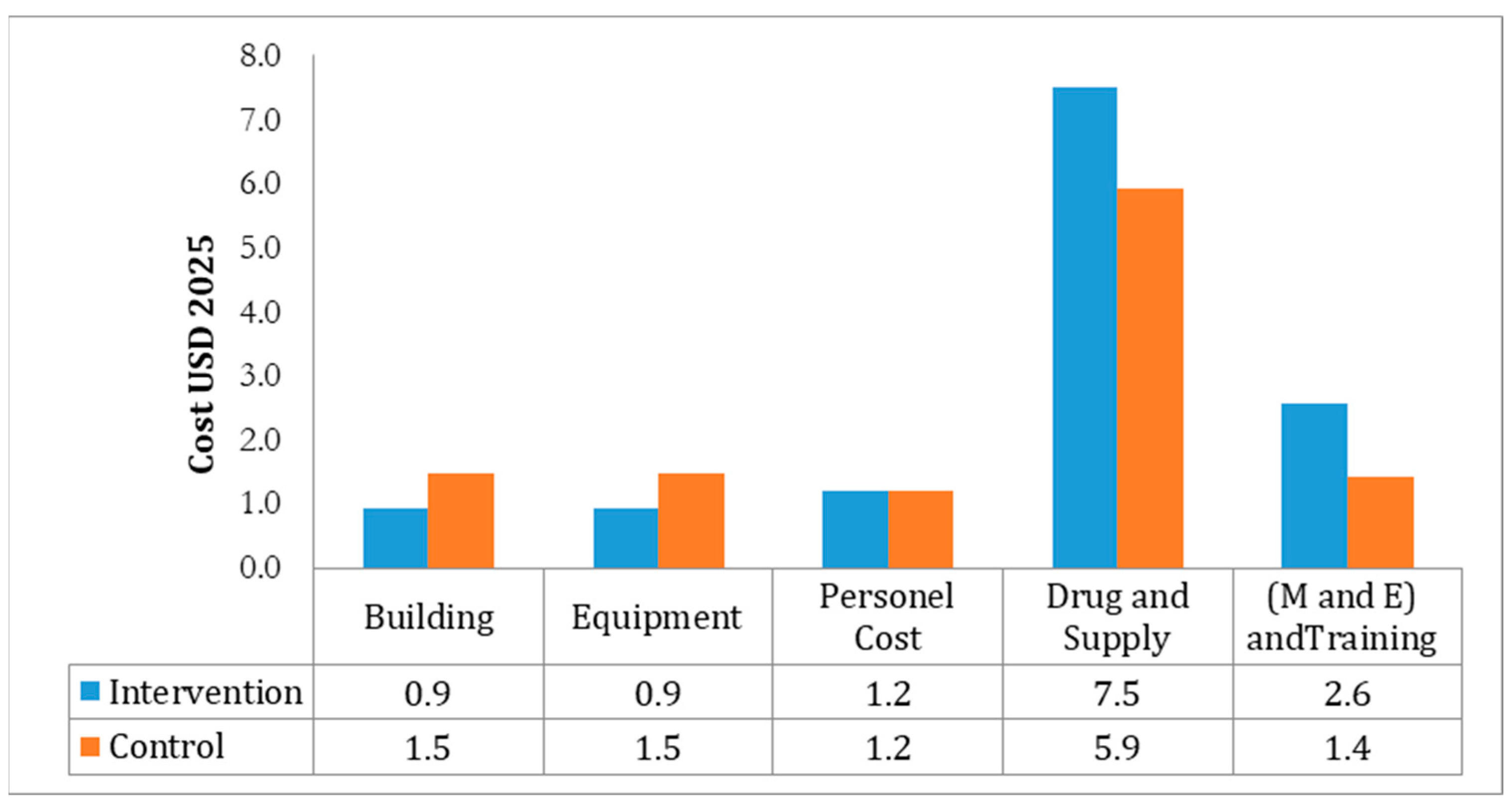

3.2. Comparative Cost Breakdown Between Intervention and Control Groups

3.3. Cost-Effectiveness of Youth-Friendly Health Services (YFHS) Program

3.4. Cost-Effectiveness and Impact Metrics

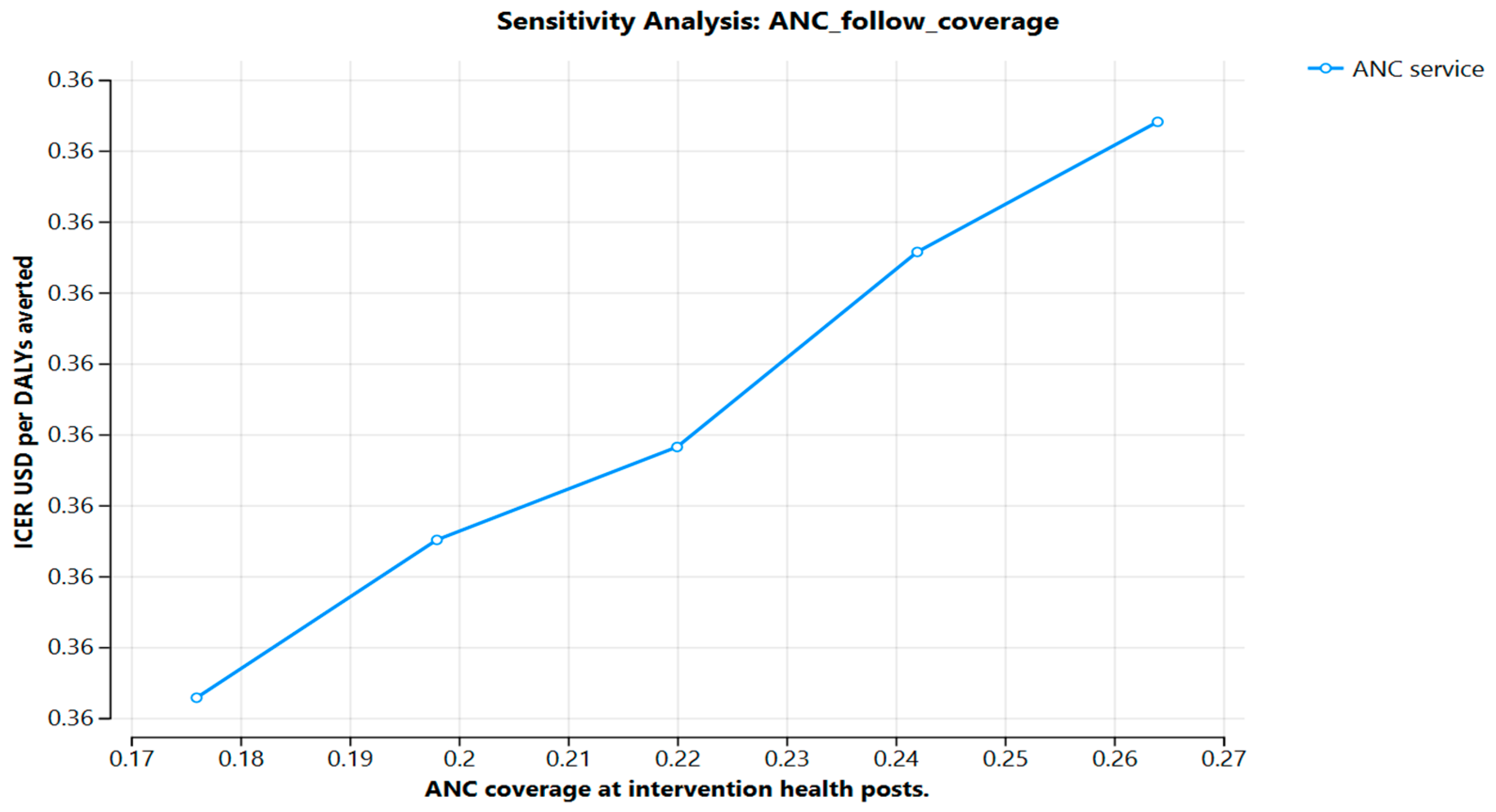

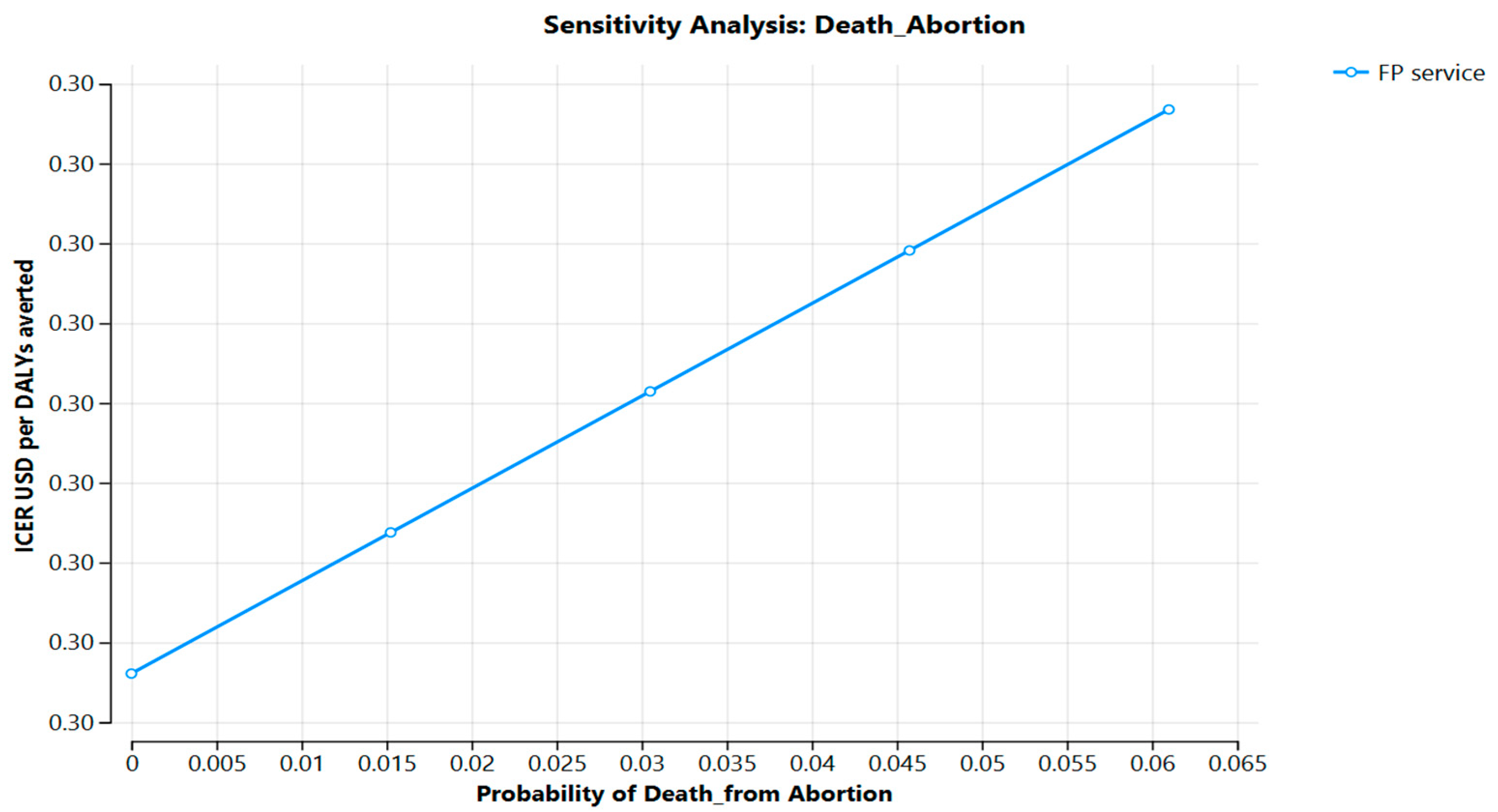

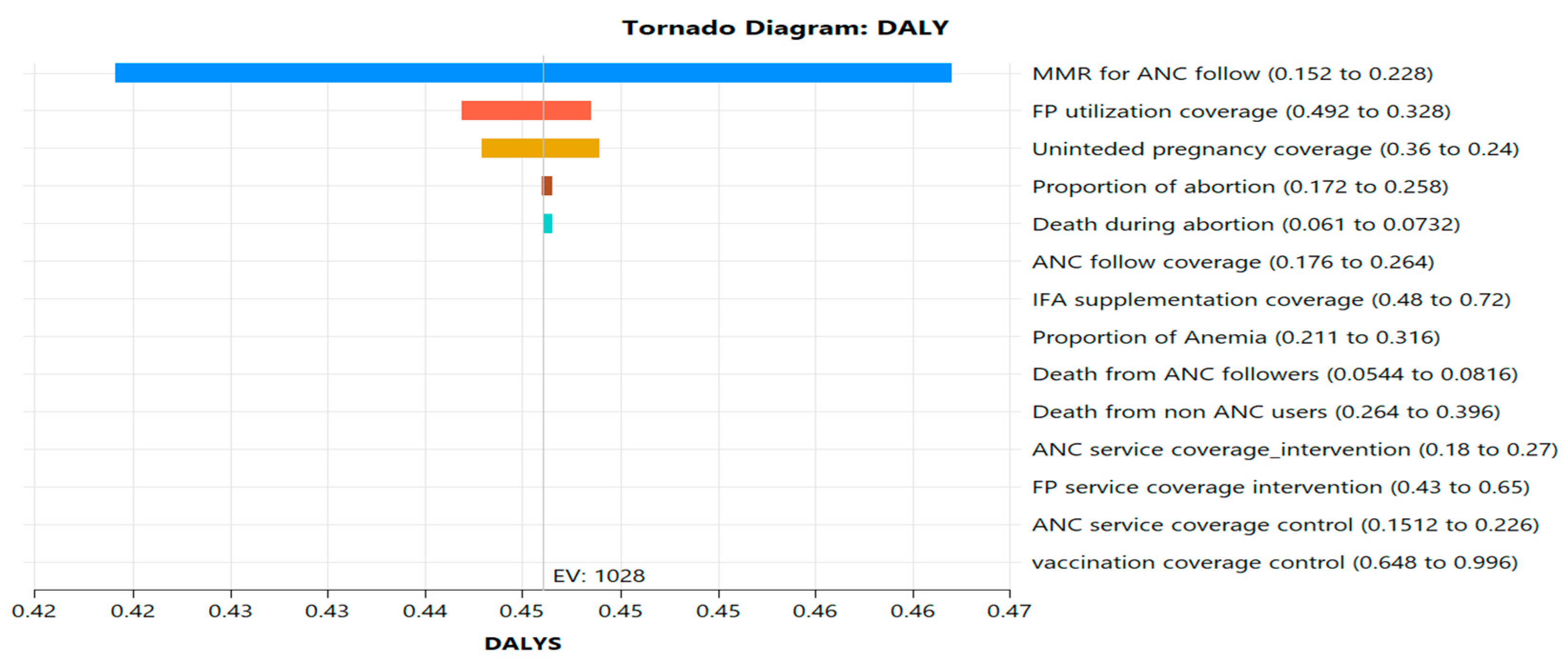

3.5. Probabilistic Sensitivity Analysis (PSA)

3.6. Cost-Effectiveness Acceptability

Key Cost Drivers and Scenario Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Becker, G.S. Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis, with Special Reference to Education; National Bureau of Economic Research: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Kearney, M.S.; Levine, P.B. Why is the teen birth rate in the United States so high and why does it matter? J. Econ. Perspect. 2012, 26, 141–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canning, D.; Schultz, T.P. The economic consequences of reproductive health and family planning. Lancet 2012, 380, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psacharopoulos, G.; Patrinos, H.A. Returns to investment in education: A decennial review of the global literature. Educ. Econ. 2018, 26, 445–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobsson, C.; Sanghavi, R.; Nyamiobo, J.; Maloy, C.; Mwanzu, A.; Venturo-Conerly, K.; Mostert, C.; Peterson, S.; Kumar, M. Adolescent and youth-friendly health interventions in low-income and middle-income countries: A scoping review. BMJ Glob. Health 2024, 9, e013393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Guidelines for Adaptation of the WHO Orientation Programme on Adolescent Health for Health Care Providers in Europe and Central Asia; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Obiezu-Umeh, C.; Nwaozuru, U.; Mason, S.; Gbaja-Biamila, T.; Oladele, D.; Ezechi, O.; Iwelunmor, J. Implementation strategies to enhance youth-friendly sexual and reproductive health services in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. Front. Reprod. Health 2021, 3, 684081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassew, T.; Tarekegn, G.E.; Alamneh, T.S.; Kassa, S.F.; Liyew, B.; Terefe, B. The prevalence and determinant factors of substance use among the youth in Ethiopia: A multilevel analysis of Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1234567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Tesfaye, R.; Ramana, G.N.V.; Chekagn, C.T. Ethiopia Health Extension Program: An Institutionalized Community Approach for Universal Health Coverage; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/24119 (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Kereta, W.; Belayihun, B.; Hagos, K.L.; Molla, Y.B.; Pirzadeh, M.; Asnake, M. Youth-friendly health services in Ethiopia: What has been achieved in 15 years and what remains to be done. Ethiop. J. Health Dev. 2021, 35, 70–77. [Google Scholar]

- Alamdo, A.G.; Debelle, F.A.; Gatheru, P.M.; Manu, A.; Enos, J.Y.; Yirtaw, T.G. Youth-friendly health service in Ethiopia: Assessment of care friendliness and user satisfaction. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0307142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muriithi, F.G.; Banke-Thomas, A.; Forbes, G.; Gakuo, R.W.; Thomas, E.; Gallos, I.D.; Devall, A.; Coomarasamy, A.; Lorencatto, F. A systematic review of behaviour change interventions to improve maternal health outcomes in sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2024, 4, e0002950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salam, R.A.; Das, J.K.; Lassi, Z.S.; Bhutta, Z.A. Adolescent health interventions: Conclusions, evidence gaps, and research priorities. BMJ Glob. Health 2023, 8, e010960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, M.; Huang, K.Y.; Othieno, C.; Wamalwa, D.; Madeghe, B.; Osok, J.; Njuguna, S. Adolescent health interventions by community health workers: A systematic review. Am. J. Public Health 2021, 111, e1–e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ethiopia Federal Ministry of Health. The National Adolescent and Youth Health Strategy (2021–2025); Ministry of Health: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2021.

- Chandra-Mouli, V.; Svanemyr, J.; Amin, A.; Fogstad, H.; Say, L.; Girard, F.; Temmerman, M. Twenty years after International Conference on Population and Development: Where are we with adolescent sexual and reproductive health and rights? J. Adolesc. Health 2015, 56, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempers, J.; Ketting, E.; Lesco, G. Cost analysis and exploratory cost-effectiveness of youth-friendly sexual and reproductive health services in the Republic of Moldova. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaud, T.L.; Pereira, E.; Porter, G.; Golden, C.; Hill, J.; Kim, J.; Wang, H.; Schmidt, C.; Estabrooks, P.A. Scoping review of costs of implementation strategies in community, public health, and healthcare settings. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e060785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daroudi, R.; Akbari Sari, A.; Nahvijou, A.; Faramarzi, A. Cost per DALY averted in low-, middle-, and high-income countries: Evidence from the global burden of disease study to estimate the cost-effectiveness thresholds. Cost Eff. Resour. Alloc. 2021, 19, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Chase, L.E.; Wagnild, J.; Akhter, N.; Sturridge, S.; Clarke, A.; Chowdhary, P.; Mukami, D.; Kasim, A.; Hampshire, K. Community health workers and health equity in low- and middle-income countries: Systematic review and recommendations for policy and practice. Int. J. Equity Health 2022, 21, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langat, E.C.; Mohiddin, A.; Kidere, F.; Omar, A.; Akuno, J.; Naanyu, V.; Temmerman, M. Challenges and opportunities for improving access to adolescent and youth sexual and reproductive health services and information in the coastal counties of Kenya: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denno, D.M.; Hoopes, A.J.; Chandra-Mouli, V. Effective Strategies to Provide Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health Services and to Increase Demand and Community Support. J. Adolesc. Health 2015, 56, 22–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Neve, J.W.; Fink, G.; Subramanian, S.V.; Moyo, S.; Bor, J. Length of secondary schooling and risk of HIV infection in Botswana: Evidence from a natural experiment. Lancet Glob. Health 2015, 3, e470–e477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meuwissen, L.E.; Gorter, A.C.; Knottnerus, A.J.A. Impact of accessible sexual and reproductive health care on poor and underserved adolescents in Managua, Nicaragua: A quasi-experimental intervention study. Health Policy Plan. 2006, 21, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Teferi, D.; Samuel, S.; Markos, M. Utilization of youth friendly reproductive health services and associated factors among secondary school students in Southern Ethiopia, 2019: School-based cross-sectional study. PAMJ 2022, 43, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assefa, Y.; Gelaw, Y.A.; Hill, P.S.; Taye, B.W.; Van Damme, W. Community health extension program of Ethiopia, 2003–2018: Successes and challenges toward universal coverage for primary healthcare services. Glob. Health 2019, 15, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TreeAge Software, Inc. TreeAge Pro 2025; TreeAge Software, Inc.: Williamstown, MA, USA, 2025; Available online: https://www.treeage.com (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- GBD 2019 Adolescent Mortality Collaborators. Global, regional, and national mortality among young people aged 10–24 years, 1950–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2021, 398, 1593–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masters, S.; Irwin, G.; Bishop, J. Benefit-cost analysis in program evaluation. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 1978, 2, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghi, J.; Gorter, A.; Sandiford, P.; Segura, Z. The cost-effectiveness of a competitive voucher scheme to reduce sexually transmitted infections in high-risk groups in Nicaragua. Health Policy Plan. 2005, 20, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Program | Service Type | Building | Equipment | Personnel | Supply | M and E and Training |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family Planning | Provision of short-term contraceptive (COC) | 1.92 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.76 | 0.16 |

| Family Planning | Provision of short-term contraceptive (condom) | 0.96 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.76 | 0.16 |

| Family Planning | Provision of short-term contraceptive (injectables) | 3.83 | 0.25 | 0.11 | 0.76 | 0.16 |

| Family Planning | Provision of long-term contraceptive (implant) | 0.96 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.76 | 0.16 |

| Maternal Health | Provision of ANC (three) | 0.96 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.55 | 0.16 |

| Maternal Health | Provision of ANC (seven) | 0.96 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.55 | 0.16 |

| Maternal Health | Provision of TD 2+ vaccination for pregnant | 0.96 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.48 | 0.16 |

| Maternal Health | Provision of TD2+ vaccination for non-pregnant | 0.96 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.48 | 0.16 |

| Maternal Health | Provision of iron and folic acid supplementation for the mother | 0.96 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.40 | 0.16 |

| Maternal Health | Provision of early postnatal care (PNC) | 0.96 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.55 | 0.16 |

| Disease Control | Prevention of DM and hypertension | 0.96 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.16 |

| Disease Control | HIV/AIDs health education counseling | 1.92 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.14 | 0.16 |

| Disease Control | STI HE/counseling | 1.92 | 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.16 |

| Nutrition | Nutritional counseling | 0.96 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.76 | 0.16 |

| Injury management | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.16 | |

| Malaria Prevention and Control | Counseling and psychosocial assessment | 0.96 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.14 | 0.16 |

| Disease Control | Referral for HIV and other STI screening | 0.96 | 0.01 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.16 |

| Disease Control | HPV vaccination | 0.96 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.48 | 0.16 |

| Program | Service Type | Building | Equipment | Personnel | Supply | M and E and Training |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family Planning | Provision of short-term contraceptive (COC) | 0.90 | 0.13 | 0.06 | 1.08 | 0.07 |

| Family Planning | Provision of short-term contraceptive (condom) | 00 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 1.08 | 0.07 |

| Family Planning | Provision of short-term contraceptive (injectables) | 4.79 | 0.28 | 0.11 | 1.08 | 0.07 |

| Family Planning | Provision of long-term contraceptive (implant) | 1.20 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 1.08 | 0.07 |

| Maternal Health | Provision of ANC (three) | 1.20 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.78 | 0.07 |

| Maternal Health | Provision of ANC (seven) | 1.20 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.78 | 0.07 |

| Maternal Health | Provision of TD2+ vaccination for pregnant | 1.20 | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.66 | 0.07 |

| Maternal Health | Provision of TD2+ vaccination for non-pregnant | 1.20 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.66 | 0.07 |

| Maternal Health | Provision of iron and folic acid supplementation for the mother | 1.20 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.63 | 0.07 |

| Maternal Health | Provision of Early Postnatal care (PNC) | 1.20 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.78 | 0.07 |

| Disease Control | Risk assessment and prevention of DM and hypertension | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 00 | 0.07 |

| Disease Control | HIV/AIDs health education counseling | 2.39 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.16 | 0.07 |

| Disease Control | STI health education/counseling | 2.39 | 0.09 | 0.14 | 0.16 | 0.07 |

| Nutrition | Nutritional counseling | 1.20 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 1.08 | 0.07 |

| Injury management | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.07 | ||

| Malaria Prevention and Control | Counselling and psychosocial assessment | 1.20 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.16 | 0.07 |

| Disease Control | Referral for HIV and other STI screening | 1.20 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.16 | 0.07 |

| Disease Control | HPV vaccination | 1.20 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.66 | 0.07 |

| Cost, Effectiveness, Average and Incremental Cost-Effectiveness Ratio per DALYs Averted. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strategy | Cost (USD) | Incremental Cost | Eff (DALYs) | Incremental Eff | ICER |

| Health post control | 4.96 | 26.42 | |||

| Health post intervention | 6.25 | 1.26 | 52.11 | 25.69 | 25.50 |

| Indicator | Intervention Group | Control Group | Net Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Costs (USD) | |||

| Total program cost | 29,680 | 7519 | +22,161 |

| Cost per service user | 3.01 | 3.73 | −0.72 |

| Health Outcomes | |||

| DALYs averted (total) | 52.11 | 26.42 | +25.69 |

| Years of healthy life gained 1 | 52.11 | 26.42 | +25.69 |

| Equivalent deaths avoided 2 | 1.74 | 0.88 | +0.86 |

| Service Coverage | |||

| ANC service utilization | 22.4% | 18.9% | +3.5% |

| Family planning utilization | 54.9% | 50.7% | +4.2% |

| HPV vaccination coverage | 74.0% | 24.5% | +49.5% |

| Cost-effectiveness | |||

| ICER (USD per DALY averted) | 25.50 | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Assefa, G.M.; Muluneh, M.D.; Abebe, S.; Addisu, G.; Yeshanehe, W. Cost-Effectiveness of Youth-Friendly Health Services in Health Post Settings in Jimma Zone, Ethiopia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1179. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081179

Assefa GM, Muluneh MD, Abebe S, Addisu G, Yeshanehe W. Cost-Effectiveness of Youth-Friendly Health Services in Health Post Settings in Jimma Zone, Ethiopia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(8):1179. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081179

Chicago/Turabian StyleAssefa, Geteneh Moges, Muluken Dessalegn Muluneh, Sintayehu Abebe, Genetu Addisu, and Wendemagegn Yeshanehe. 2025. "Cost-Effectiveness of Youth-Friendly Health Services in Health Post Settings in Jimma Zone, Ethiopia" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 8: 1179. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081179

APA StyleAssefa, G. M., Muluneh, M. D., Abebe, S., Addisu, G., & Yeshanehe, W. (2025). Cost-Effectiveness of Youth-Friendly Health Services in Health Post Settings in Jimma Zone, Ethiopia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(8), 1179. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081179