Health and Safety Challenges in South African Universities: A Qualitative Review of Campus Risks and Institutional Responses

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Problem

1.2. The Aim

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

Theoretical and Analytical Framework

2.2. Study Population and Scope

2.3. Data Sources

- Policy Documents: An analysis of National frameworks and legislation guiding university safety standards.

- Academic Literature: An analysis of journal articles focusing on health, safety, and student welfare in higher education settings was conducted. These sources serve as foundational knowledge and inform our analysis.

- Government Crime Reports: To capture recent incidents, we examined government South African Police Service (SAPS) data on campus crime trends within South African universities. These reports provide empirical data on security challenges faced by academic communities.

- Official University Statements: The authors also scrutinised institutional press releases and public reports on incidents.

- Media Articles: Verified national media coverage related to safety incidents in universities.

2.4. Document Selection

- The document must refer explicitly to a South African university.

- It must describe or report a safety-related incident between 2015 and 2024.

- It must originate from a credible source (e.g., official press, SAPS, university, or peer-reviewed literature).

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. National Context: Crime Trends in the Education Sector

3.1.1. Number of Incidents in Educational Institutions per Province in South Africa in 2023

3.1.2. Number of Incidents in Educational Institutions per Province in South Africa in 2024

3.1.3. The 2023 and 2024 Crimes Comparison and Analysis of Trends

3.2. Campus Safety Incidents Within South African Universities: Media Output

Murders

3.3. Gender-Based Violence Incidents (GBV) on Campus

3.4. Unsafe Infrastructure and Student Housing Conditions

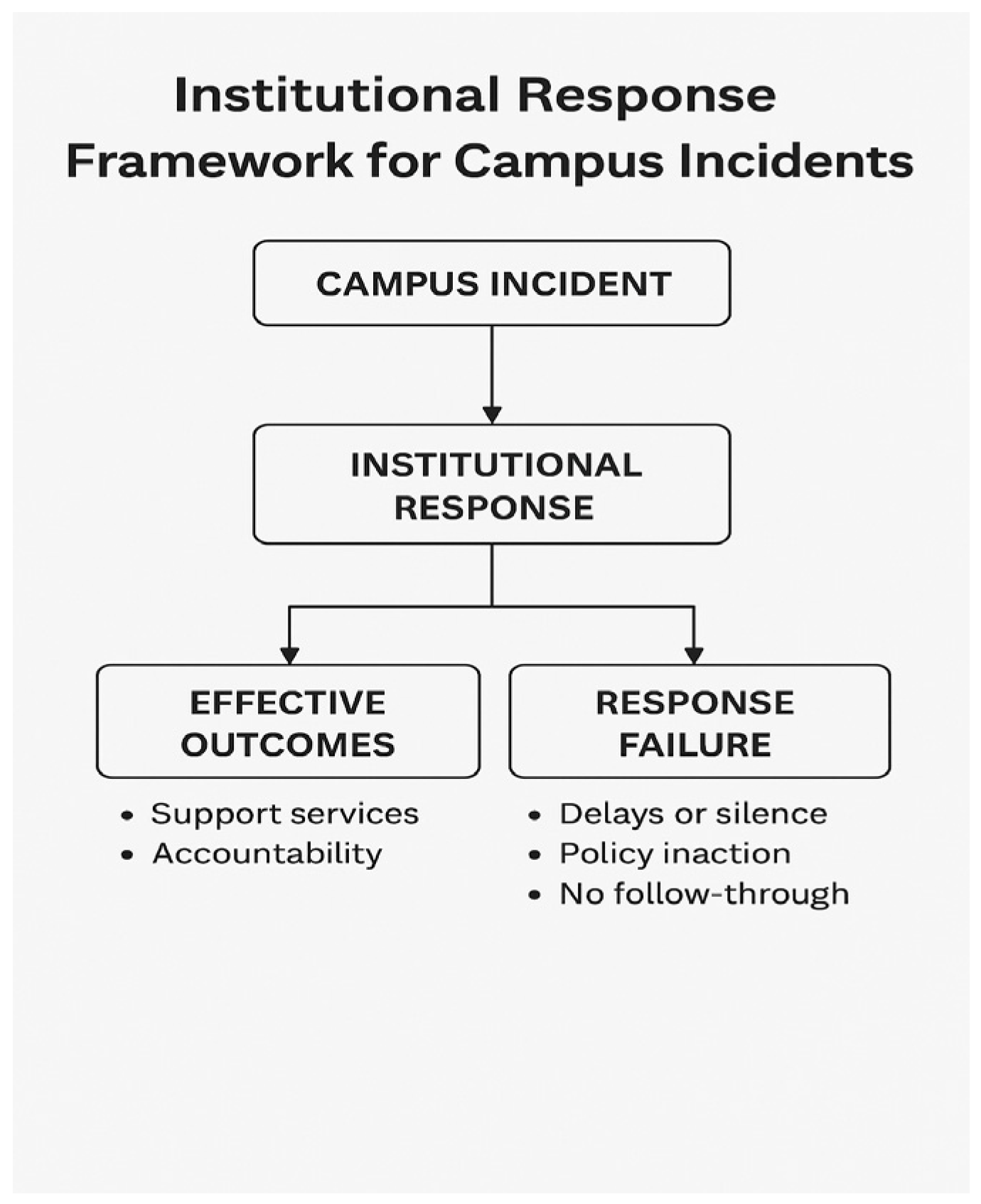

3.5. Institutional Policy and Response Gaps

4. Discussion

4.1. Well-Being of Students

4.2. Analysis of Crime Incidents per Province

4.3. The Role and Contribution of Victimology in Incidents

4.4. Policy Implementation Gaps in South African Universities

4.4.1. Inadequate Funding

4.4.2. Monitoring and Enforcement Challenges

5. Conclusions

5.1. Recommendations for Improving Health and Safety in South African Universities

5.2. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Definition |

| GBV | Gender-Based Violence |

| DHET | Department of Higher Education and Training |

| SAPS | South African Police Service |

| MH | Mental Health |

| PTSD | Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder |

References

- Occupational Health and Safety Act 85 of 1993. Available online: https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/act85of1993.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2023).

- South African Department of Labour (DOL). The Profile of Occupational Profile of Occupational Health and Safety South Africa. 2020. Available online: https://www.labour.gov.za/DocumentCenter/Publications/Occupational%20Health%20and%20Safety/The%20Profile%20Occupational%20Health%20and%20Safety%20South%20Africa.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2023).

- University of KwaZulu-Natal. Link Between Campus Safety, Security and Student Retention Under the Spotlight. 2023. Available online: https://ww1.caes.ukzn.ac.za/news/link-between-campus-safety-security-and-student-retention-under-the-spotlight/#:~:text=The%20important%20issue%20of%20safety,GBV)%20in%20higher%20learning%20institutions (accessed on 13 November 2023).

- Rhodes University. Safety. 2021. Available online: https://www.ru.ac.za/safety/ (accessed on 13 November 2023).

- Makhaye, M. Crime in Institutions of Higher Learning. 2023. Available online: https://www.saferspaces.org.za/understand/entry/crime-in-institutions-of-higher-learning. (accessed on 18 December 2023).

- Mkhize, S.; Cinini, F.; Ngcece, S. University campuses and types of crime: A case study of the University of KwaZulu-Natal/Howard campus in the city of Durban-South Africa. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2022, 8, 2110199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopal, N.; Van Niekerk, C. Safety in Student Residences Matters! S. Afr. J. High. Educ. 2018, 32, 172–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adisa, S.; Simpeh, F.; Fapohunda, J. Evaluation of Safety and Security Measures: Preliminary Findings of a University Student Housing Facility in South Africa. In The Construction Industry in the Fourth Industrial Revolution; CIDB 2019; Aigbavboa, C., Thwala, W., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brink, J.; Mdaka, Q.; Matee, L. Practitioner’s Perspectives on a National South African Higher Education Institution Policy Framework Mitigating Gender-Based Violence. Int. J. Crit. Divers. Stud. 2022, 4, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moosa, A.; Ohei, K.; Raymond, E.; Chukwuneme, E. The Roles of Campus Protection Services for Students’ Safety: A Case of a Higher Education Institution in South Africa. Khazanah Pendidik. Islam 2022, 3, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Times Higher Education. World University Rankings. 2024. Available online: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/world-university-rankings (accessed on 13 November 2023).

- FundiConnect. Top 10 Universities in South Africa: 2024 Edition. 2024. Available online: https://fundiconnect.co.za/top-10-universities-south-africa/ (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- Business Tech. 2024 Ranking of ALL 26 universities in South Africa. 2024. Available online: https://businesstech.co.za/news/lifestyle/747320/2024-ranking-of-all-26-universities-in-south-africa/ (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- South African. Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996 (Act No. 108 of 1996). Available online: https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/images/a108-96.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- South African. Basic Conditions for Employment Act 75 of 1997. Available online: https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/a75-97.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- South African. National Building Regulations and Building Standards Act 103 of 1977. Available online: https://www.gov.za/documents/national-building-regulations-and-building-standards-act-16-apr-2015-1302 (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- South African. National Environmental Management Act 107 of 1998. Available online: https://www.gov.za/documents/national-environmental-management-act (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- South African. Disaster Management Act 57 of 2002. Available online: https://www.gov.za/documents/disaster-management-act (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- South African Department of Health. Occupational Health and Safety Policy for the National Department of Health. 2006. Available online: https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/ohs.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- University of Cape Town (UCT). Health and Safety. 2023. Available online: https://health.uct.ac.za/home/health-and-safety (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- Security Industry Association. Higher Security for Higher Education: Achieving Safe, Secure Learning Environments. 2019. Available online: https://www.securityindustry.org/2019/09/06/higher-security-for-higher-education-achieving-safe-secure-learning-environments/ (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- Ahmed, S.; Mazri, T. Security Approaches for Smart Campus; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Makhaye, M.S.; Mkhize, S.M.; Sibanyoni, E.K. Female students as victims of sexual abuse at institutions of higher learning: Insights from KwaZulu-Natal. SN Soc. Sci. 2023, 3, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dlamini, N.; Olanrewaju, O.A. An Investigation into Campus Safety and Security. 2021. Available online: http://www.ieomsociety.org/singapore2021/papers/45.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- Greeff, M.; Mostert, K.; Jonke, C. The #FeesMustFall protests in South Africa: Exploring first-year students’ experiences at a peri-urban university campus. S. Afr. J. High. Educ. 2021, 35, 78–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- South African Government. Media Statements. Minister Blade Nzimande on the continuing murder of Post School Education and Training Students. 2023. Available online: https://www.gov.za/news/media-statements/minister-blade-nzimande-continuing-murder-post-school-education-and-training (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- South African Police Service. Police Recorded Crime Statistics Republic of South Africa. 2023. Available online: https://www.saps.gov.za/services/crimestats.php (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- South African Police Service. Police Recorded Crime Statistics Republic of South Africa: First Quarter of 2024–2025 Financial Year (April 2024 to June 2024). 2024. Available online: https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/crimestats.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- South African Police Service. Police Recorded Crime Statistics Republic of South Africa: Second Quarter of 2024–2025 Financial Year (July 2024 to September 2024). 2024. Available online: https://www.saps.gov.za/services/downloads/2024/2024-2025_Q2_crime_stats.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- South African Police Service. Police Recorded Crime Statistics Republic of South Africa: Fourth Quarter of 2023-2024 Financial Year (January 2024 to March 2024). 2024. Available online: https://www.saps.gov.za/services/downloads/2024/2023-2024_-_4th_Quarter_WEB.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- DA. Minister of Police Must Address Alarming Crime Rates in Educational Institutions. 2024. Available online: https://www.da.org.za/2024/11/minister-of-police-must-address-alarming-crime-rates-in-educational-institutions (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- Mail and Guardian. Protesters set building alight at University of KwaZulu-Natal. 2023. Available online: https://mg.co.za/education/2023-08-22-protesters-set-building-alight-at-university-of-kwazulu-natal/ (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- University of Johannesburg. UJ Annual Report 2022. 2022. Available online: https://www.uj.ac.za/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/annual-report-2022.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- The Africa Report. South Africa’s Universities Swamped by Corruption, Organised Crime. 2023. Available online: https://www.theafricareport.com/318367/south-africas-universities-swamped-by-corruption-organised-crime/ (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- Timeslive. Nzimande Was Outraged After Nine Students Attacked, Murdered in One Month. 2023. Available online: https://www.timeslive.co.za/news/south-africa/2023-02-27-nzimande-outraged-after-nine-students-attacked-murdered-in-one-month/ (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- News24. Man accused of TUT student Ntokozo Xaba’s murder appears in court. 2023. Available online: https://www.news24.com/southafrica/news/man-accused-of-tut-student-ntokozo-xabas-murder-appears-in-court-20230206 (accessed on 13 November 2023).

- George Herald. 2023. Available online: https://www.georgeherald.com/News/Article/General/student-killed-on-nmu-campus-202306080748 (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- News24. Fort Hare Student Stabbed to Death Allegedly over Missing Laptop. 2023. Available online: https://www.news24.com/news24/southafrica/news/fort-hare-student-stabbed-to-death-allegedly-over-missing-laptop-20231008 (accessed on 13 November 2023).

- SABC News. Cape Town Student Stabbed, Suspect Arrested. 2023. Available online: https://www.sabcnews.com/sabcnews/893224-2/ (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- Mail and Guardian. Student Fatally Shot in DUT Protests. 2019. Available online: https://mg.co.za/article/2019-02-05-dut-student-shot-killed/ (accessed on 18 December 2023).

- University of Cape Town Report on Crime Criminality at, U.C.T. 2018. Available online: https://www.news.uct.ac.za/downloads/reports/vc-to-council/2018-10-13_ReportToCouncil_02b1b_Crime_and_criminality.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- University World News. Universities Making Campuses Safer After 47 Rapes in 2017. 2018. Available online: https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20181009130251203 (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- Council on Higher Education (CHE). Gender-Based Violence in South African Universities: An Institutional Challenge. 2019. Available online: https://www.che.ac.za/sites/default/files/publications/BS%2010_Gender-based%20violence%20in%20South%20African%20universities_An%20institutional%20challenge.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- Visagie, J.; Turok, I.; Swartz, S. What Lies Behind Social Unrest in South Africa, and What Might Be Done About It? 2021. Available online: https://theconversation.com/what-lies-behind-social-unrest-in-south-africa-and-what-might-be-done-about-it-166130 (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- DDP 2021. Police Brutality and Student Protest in South Africa. Available online: https://ddp.org.za/blog/2021/04/15/police-brutality-and-student-protest-in-south-africa/ (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- Mncube, V.; Mutongoza, B.; Olawale, B. Managing higher education institutions in the context of Covid-19 stringency: Experiences of stakeholders at a rural South African university. Perspect. Educ. 2021, 39, 390–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpeh, F.; Akinlolu, M. A comparative analysis of the provision of student housing safety measures. J. Facil. Manag. 2021, 19, 377–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpeh, F.; Adisa, S. On-campus student accommodation safety measures: Provision versus risk analysis. Int. J. Build. Pathol. Adapt. 2022, 40, 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adisa, S.; Simpeh, F. A comparative analysis of student housing security measures. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 654, 012017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mead, C.; Price, C.; Gin, L.E.; Anbar, A.D.; Collins, J.P.; LePore, P.; Brownell, S.E. A comparative case study of the accommodation of students with disabilities in online and in-person degree programs. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0288748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magni, M.; Pescaroli, G.; Bartolucci, A. Factors influencing university students’ accommodation choices: Risk perception, safety, and vulnerability. J. Hous. Built. Environ. 2019, 34, 791–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutinta, G. Mental distress among university students in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. BMC Psychol. 2022, 10, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naji, G.M.A.; Isha, A.S.N.; Mohyaldinn, M.E.; Leka, S.; Saleem, M.S.; Rahman, S.M.N.B.S.A.; Alzoraiki, M. Impact of Safety Culture on Safety Performance; Mediating Role of Psychosocial Hazard: An Integrated Modelling Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Welde, K. Gender-based violence on campuses: National context and institutional inertia. Gend. Soc. 2017, 31, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valls, R.; Puigvert, L.; Melgar, P. Breaking the silence at Spanish universities: Findings from the first study of gender violence. Violence Against Women 2016, 22, 1519–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNESCO. Ending Gender-Based Violence in Universities: Global Guidelines and Good Practices. 2021. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000380474 (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- Sabina, C.; Ho, L.Y. Campus sexual assault: A systematic review of prevalence research from 2000 to 2012. Trauma Violence Abus. 2014, 15, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Element | Description |

|---|---|

| Focus | Prevention of harm (injury, violence, disease) across populations |

| Level of Analysis | Structural, environmental, and systemic factors, not just individual acts |

| Assumptions | Most harm is preventable, not inevitable |

| Methods | Uses surveillance data, risk assessments, and root cause analysis |

| Intervention Strategy | Emphasises multi-level, multi-sectoral solutions (policy, design, education) |

| Example Issues | GBV, mental health, poor housing, school violence, substance abuse |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sepadi, M.M.; Chadyiwa, M. Health and Safety Challenges in South African Universities: A Qualitative Review of Campus Risks and Institutional Responses. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 989. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22070989

Sepadi MM, Chadyiwa M. Health and Safety Challenges in South African Universities: A Qualitative Review of Campus Risks and Institutional Responses. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(7):989. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22070989

Chicago/Turabian StyleSepadi, Maasago Mercy, and Martha Chadyiwa. 2025. "Health and Safety Challenges in South African Universities: A Qualitative Review of Campus Risks and Institutional Responses" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 7: 989. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22070989

APA StyleSepadi, M. M., & Chadyiwa, M. (2025). Health and Safety Challenges in South African Universities: A Qualitative Review of Campus Risks and Institutional Responses. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(7), 989. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22070989