Locating Meaning: Health Professionals’ Views on the Psychological and Clinical Significance of Self-Injury Sites

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Psychological and Clinical Significance of Self-Injury Location

1.2. Health Professionals’ Views About Self-Injury Location

1.3. Aims of the Study

- (1)

- What do staff think about the clinical risk associated with self-injuring in concealed and visible locations? We speculated that professionals may view cutting near major blood vessels (e.g., the neck) as more clinically risky and associated with suicidal intent, mirroring findings from studies of those who self-injure. We also explored whether staff perceived cutting in visible areas as less clinically risky, potentially because visibility communicates the need for medical attention and support.

- (2)

- What do staff think about the distress experienced when individuals self-injure in concealed and visible locations? We explored whether staff made any location or visibility-based attributions about distress.

- (3)

- What do staff think about the functions of self-injury in concealed and visible locations? We reasoned that staff may be more likely to attribute concealed cutting to intrapersonal (affect regulatory) functions, because the hidden nature of the injury may prevent attributions such as “attention-seeking”. In contrast, staff might assume that injuries in visible areas serve interpersonal functions, since they are physical manifestations of the need for support.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Recruitment and Sample

2.2. Ethics

2.3. Interviews

2.4. Analytical Strategy

3. Results

3.1. Inductive Thematic Analysis

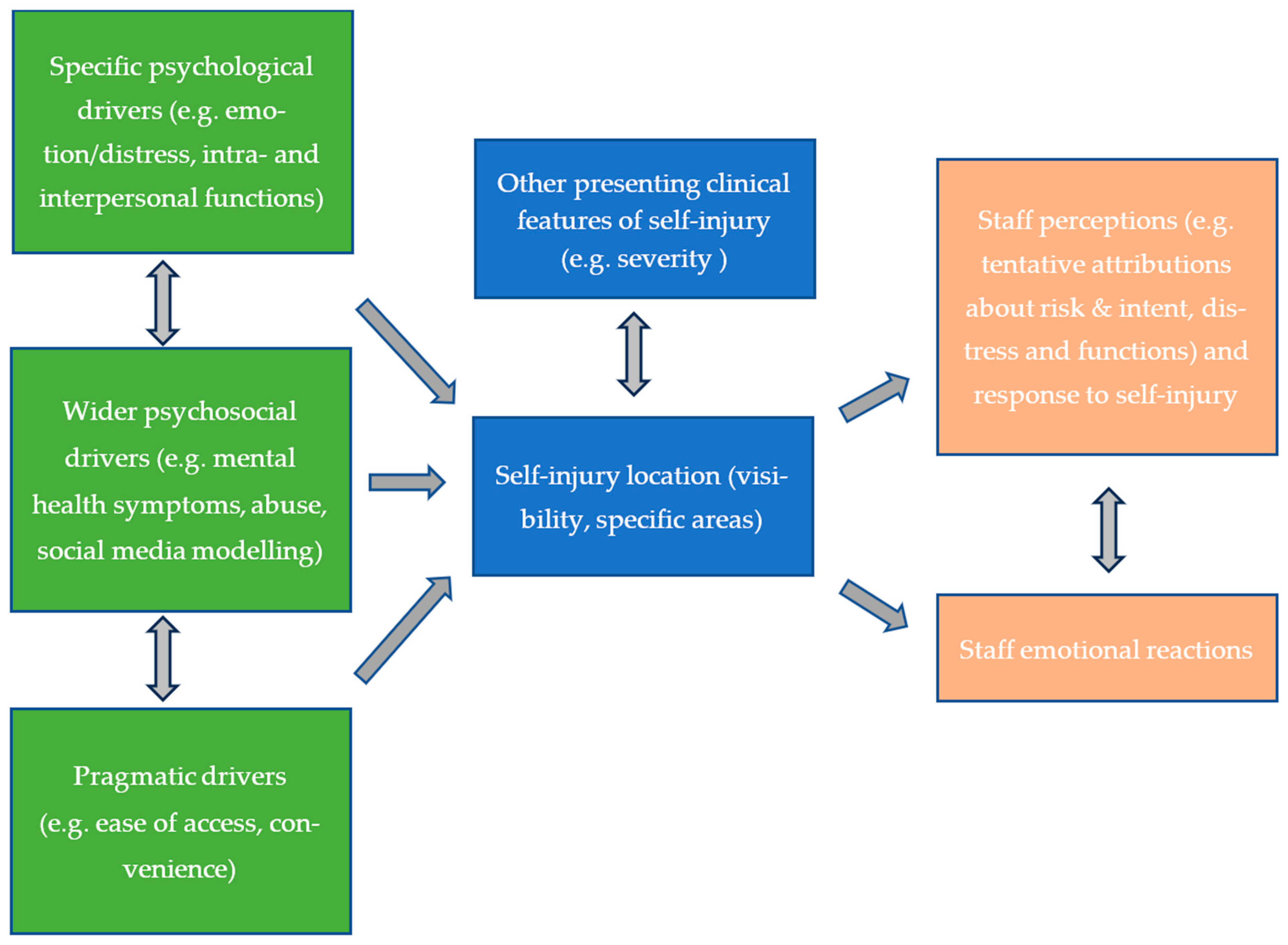

3.1.1. Theme 1: Location Drives an Appraisal of Risk

3.1.2. Theme 2: Driven by Emotion and Selecting a Location of Relief: A Location-Based Perspective of the Intrapersonal Functions of Self-Injury

3.1.3. Theme 3: Selecting a Visible Location for Interpersonal Reasons

3.1.4. Theme 4: Contemplating the Role of Demographic Factors, Mental Health Diagnoses and Wider Experiences

3.1.5. Theme 5: A Pragmatic Perspective of Location

3.1.6. Theme 6: Location and the Bigger Picture

3.1.7. Theme 7: The Impact of Injury Location on the Staff Supporting Individuals Who Self-Injure

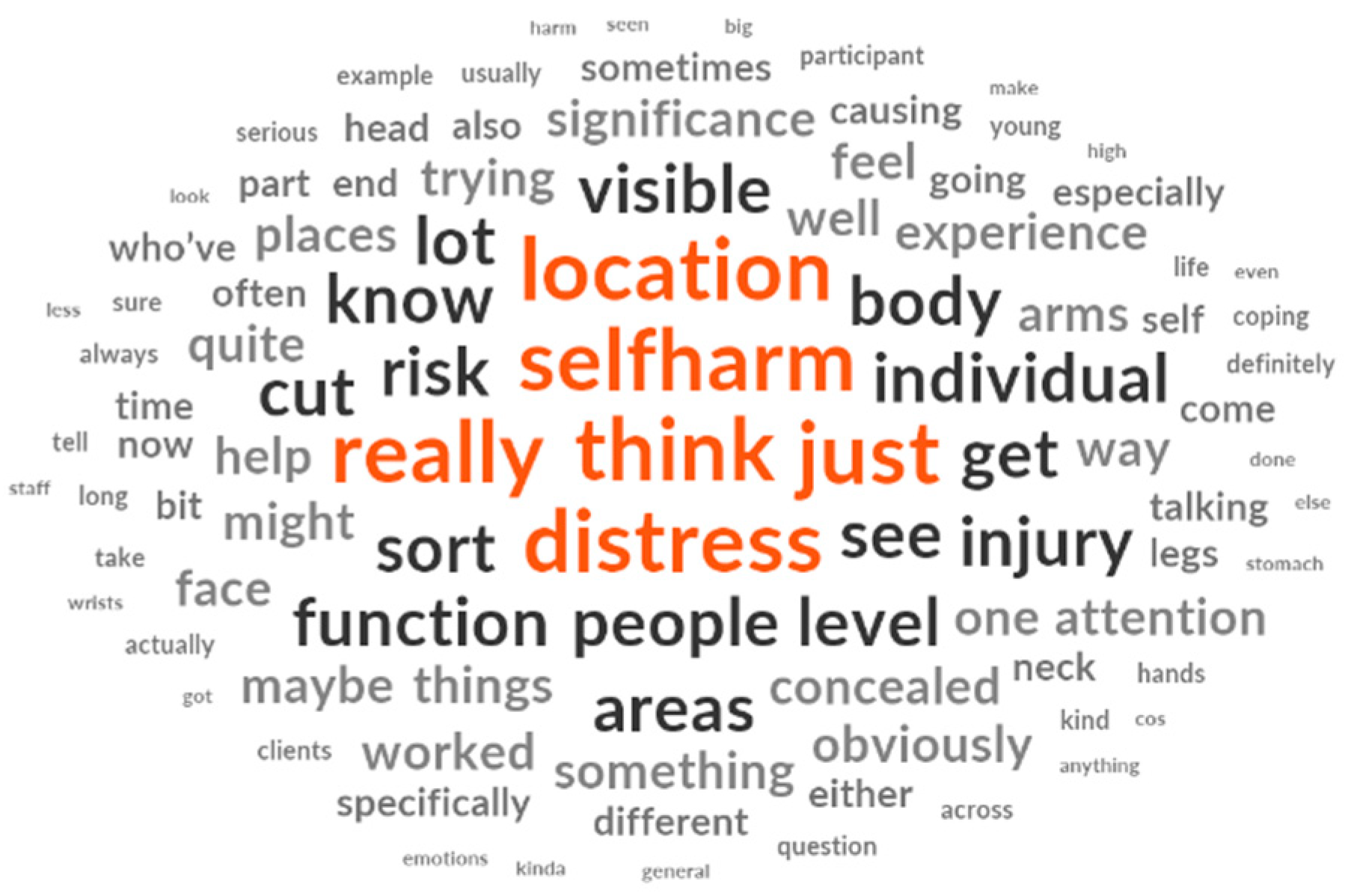

3.2. Inductive Summative Content Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations and Future Directions

4.2. Clinical and Educational Implications

Recommended Adaptations to Self-Injury and Suicide Prevention Training

- (1)

- Communication, engagement, and relational skills: Training should encourage a non-judgmental, compassionate, person-centred, and respectfully curious approach [58,59,60], irrespective of injury location. Staff should begin by building a rapport, pacing the conversation, and giving space to talk before gently beginning to explore location and other aspects of the self-injury using open-ended, supportive questions such as: “How would you like me to support you when we talk about injuries to [location X], and [location Y]?” It is conceivable that injuries in specific areas may be more difficult to talk about than others, particularly those that elicit shame or perceived stigma; hence, staff should be attuned to signs of discomfort and ensure the service user feels reassured and supported.

- (2)

- Collaborative and individualized clinical assessment skills: Staff should be trained to work jointly with service users to assess each injury episode [5] and understand whether injury location holds psychological or clinical significance for the individual. The assessment may include visually inspecting wounds, if this falls within one’s professional scope of practice [36]. Staff should adopt a stance of respectful curiosity [59,60] and might ask the service user: “What, if anything, does this injury location mean to you?”

- (3)

- Collaborative risk formulation and integration skills: Staff should be trained to incorporate injury location into individualised, dynamic, and holistic collaborative risk formulations [6,61] that empower service users and help them understand the risk posed by their self-injury in specific locations, explored in relation to their history, current difficulties, and context. Staff should embed the questions within this wider conversation and might begin: “I’m also curious about how you feel just before you injure location X?... and whether injuring this area feels more dangerous or more significant to you?”

- (4)

- Reflective practice and critical thinking skills: It is essential that training develops awareness of the potential for implicit biases and location-based perceptions, assumptions, and attributions (e.g., “visible injuries always indicate a communicative function or lower risk”) that might need challenging to avoid stigma or unintended clinical consequences, such as inaccuracies in risk assessment and formulation. This is in keeping with a trauma-informed approach to care, which can significantly reduce self-injury [44]. Staff could be trained to use the six stages of Gibbs’ reflective cycle [62] to ask themselves questions: (1) Description, “what did I see (e.g., facial self-injury)?”; (2) feelings, “how did I feel when I saw this injury”; (3) evaluation, “how helpful/unhelpful was my response?”; (4) analysis, “did I make any assumptions about this injury, and were these shaped by where the injury is on the body?”, and “did these assumptions affect my response or decision-making?”; (5) conclusion, “what else could I have done?” and (6) action plan, “what strategies can I use to manage by emotional responses if I see injuries on location X again?...what support do I need to help me provide the best care?”

- (5)

- Self-care and emotion management skills. Staff should be supported to understand and manage automatic, intense emotional reactions, such as shock, that can arise when encountering injuries, particularly in sensitive or less typical locations. These emotional reactions impact staff well-being and should also be considered through a relational lens, encouraging reflection on how different responses might influence interactions with service users. Training should cover professional self-care strategies [23] and the development of emotion regulation techniques, such as grounding and mindfulness. Equally important is the provision of role-specific organizational support structures to help staff process their emotions constructively. This might include regular supervision, team debriefs following distressing incidents, peer/colleague support, and reflective practice.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Ethics Committee Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Department of Health. Preventing Suicide in England: Third Progress Report of the Cross-Government Outcomes Strategy to Save Lives; Department of Health: London, UK, 2017. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/suicide-prevention-third-annual-report (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Office of the Surgeon General and National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention. 2012 National Strategy for Suicide Prevention: Goals and Objectives for Action; Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK109917/ (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Safety in Mental Health (NCISH). Annual Report: England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales; University of Manchester: Manchester, UK, 2018. Available online: https://www.manchester.ac.uk/ncish/reports/ (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Mars, B.; Heron, J.; Klonsky, E.D.; Moran, P.; O’Connor, R.C.; Tilling, K.; Wilkinson, P.; Gunnell, D. Predictors of Future Suicide Attempt among Adolescents with Suicidal Thoughts or Non-Suicidal Self-Harm: A Population-Based Birth Cohort Study. Lancet Psychiatry 2019, 6, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, J.D.; Franklin, J.C.; Fox, K.R.; Bentley, K.H.; Kleiman, E.M.; Chang, B.P.; Nock, M.K. Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviors as Risk Factors for Future Suicide Ideation, Attempts, and Death: A Meta-Analysis of Longitudinal Studies. Psychol. Med. 2016, 46, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. Self-Harm: Assessment, Management and Preventing Recurrence. NICE Clinical Guideline NG225; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Geulayov, G.; Casey, D.; McDonald, K.C.; Foster, P.; Pritchard, K.; Wells, C.; Clements, C.; Kapur, N.; Ness, J.; Waters, K.; et al. Incidence of Suicide, Hospital-Presenting Non-Fatal Self-Harm, and Community-Occurring Non-Fatal Self-Harm in Adolescents in England (the Iceberg Model of Self-Harm): A Retrospective Study. Lancet Psychiatry 2018, 5, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergen, H.; Hawton, K.; Waters, K.; Ness, J.; Cooper, J.; Steeg, S.; Kapur, N. How Do Methods of Non-Fatal Self-Harm Relate to Eventual Suicide? J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 136, 526–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, R.; Thomas, K.H.; Bramley, K.; Williams, S.; Griffin, L.; Potokar, J.; Gunnell, D. Self-Cutting and Risk of Subsequent Suicide. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 192, 8–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawton, K.; Bergen, H.; Kapur, N.; Cooper, J.; Steeg, S.; Ness, J.; Waters, K. Repetition of Self-Harm and Suicide Following Self-Harm in Children and Adolescents: Findings from the Multicentre Study of Self-Harm in England. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2012, 53, 1212–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olfson, M.; Wall, M.; Wang, S.; Crystal, S.; Gerhard, T.; Blanco, C. Suicide Following Deliberate Self-Harm. Am. J. Psychiatry 2017, 174, 765–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victor, S.E.; Muehlenkamp, J.J.; Hayes, N.A.; Lengel, G.J.; Styer, D.M.; Washburn, J.J. Characterizing Gender Differences in Nonsuicidal Self-Injury: Evidence from a Large Clinical Sample of Adolescents and Adults. Compr. Psychiatry 2018, 82, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horrocks, J.; Price, S.; House, A.; Owens, D. Self-Injury Attendances in the Accident and ED: Clinical Database Study. Br. J. Psychiatry 2003, 183, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, K.J.; Clements, C.; Bickley, H.; Rayner, G.; Taylor, P.T. The Significance of Location of Self-Injury. In The Oxford Handbook of Nonsuicidal Self-Injury; Lloyd-Richardson, E.E., Baetens, I., Whitlock, J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Stroehmer, R.; Edel, M.A.; Pott, S.; Juckel, G.; Haussleiter, I.S. Digital Comparison of Healthy Young Adults and Borderline Patients Engaged in Non-Suicidal Self-Injury. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2015, 14, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujioka, M.; Murakami, C.; Masuda, K.; Doi, H. Evaluation of Superficial and Deep Self-Inflicted Wrist and Forearm Lacerations. J. Hand Surg. 2012, 37, 1054–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joiner, T. Why People Die by Suicide; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Geulayov, G.; Casey, D.; Bale, E.; Brand, F.; Clements, C.; Farooq, B.; Kapur, N.; Ness, J.; Waters, K.; Patel, A.; et al. Risk of Suicide in Patients Who Present to Hospital after Self-Cutting According to Site of Injury: Findings from the Multicentre Study of Self-Harm in England. Psychol. Med. 2023, 53, 1400–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laukkanen, E.; Rissanen, M.L.; Tolmunen, T.; Kylmä, J.; Hintikka, J. Adolescent Self-Cutting Elsewhere than on the Arms Reveals More Serious Psychiatric Symptoms. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2013, 22, 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner, K.J.; Bickley, H.; Turnbull, P.; Kapur, N.; Taylor, P.; Clements, C. The Significance of Site of Cut in Self-Harm in Young People. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 266, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrigan, P.W.; Markowitz, F.E.; Watson, A.; Rowan, D.; Kubiak, M.A. An Attribution Model of Public Discrimination towards People with Mental Illness. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2003, 44, 162–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, S.; Glover, L. Hospital Staff Experiences of Their Relationships with Adults Who Self-Harm: A Meta-Synthesis. Psycesthol. Psychother. 2017, 90, 480–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, G.U.; Rostill-Brookes, H.; Goodman, D. Public Stigma in Health and Non-Healthcare Students: Attributions, Emotions and Willingness to Help with Adolescent Self-Harm. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2009, 46, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klonsky, E.D.; Glenn, C.R.; Styer, D.M.; Olino, T.M.; Washburn, J.J. The Functions of Nonsuicidal Self-Injury: Converging Evidence for a Two-Factor Structure. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2015, 9, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nock, M.K. Actions Speak Louder Than Words: An Elaborated Theoretical Model of the Social Functions of Self-Injury and Other Harmful Behaviors. Appl. Prev. Psychol. 2008, 12, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P.J.; Jomar, K.; Dhingra, K.; Forrester, R.; Shahmalak, U.; Dickson, J.M. A Meta-Analysis of the Prevalence of Different Functions of Non-Suicidal Self-Injury. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 227, 759–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, S.E.; Townsend, E.; Anderson, M.P. ‘In Two Minds’—Socially Motivated Self-Harm Is Perceived as Less Serious than Internally Motivated: A Qualitative Study of Youth Justice Staff. J. Health Psychol. 2013, 18, 1187–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akinola, P.; Rayner, G. Staff Attitudes, Beliefs and Responses towards Self-Harm: A Systematised Literature Review. Br. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2022, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, G.; Blackburn, J.; Edward, K.L.; Stephenson, J.; Ousey, K. Emergency Department Nurse’s Attitudes towards Patients Who Self-Harm: A Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2019, 28, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, K.E.; Hawton, K.; Fortune, S.; Farrell, S. Attitudes and Knowledge of Clinical Staff Regarding People Who Self-Harm: A Systematic Review. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 139, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandler, A. Seeking Secrecy: A Qualitative Study of Younger Adolescents’ Accounts of Self-Harm. Young 2018, 26, 313–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scourfield, J.; Roen, K.; McDermott, E. The Non-Display of Authentic Distress: Public-Private Dualism in Young People’s Discursive Construction of Self-Harm. Sociol. Health Illn. 2013, 35, 777–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehy, K.; Noureen, A.; Khaliq, A.; Dhingra, K.; Husain, N.; Pontin, E.E.; Cawley, R.; Taylor, P.J. An Examination of the Relationship between Shame, Guilt and Self-Harm: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2019, 73, 101779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, G.; Allen, S.L.; Johnson, M. Countertransference and Self-Injury: A Cognitive Behavioural Cycle. J. Adv. Nurs. 2005, 50, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westers, N. Should Psychotherapists Conduct Visual Assessments of Nonsuicidal Self-Injury Wounds? Psychotherapy 2024, 61, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malterud, K.; Siersma, V.D.; Guassora, A.D. Sample Size in Qualitative Interview Studies: Guided by Information Power. Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 1753–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- White, M.; Marsh, E. Content Analysis: A Flexible Methodology. Lib. Trends 2006, 55, 22–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tausczik, Y.R.; Pennebaker, J.W. The Psychological Meaning of Words: LIWC and Computerized Text Analysis Methods. J. Lang. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 29, 24–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QSR International. NVivo, Version 12; QSR International: Melbourne, Australia, 2020; Available online: https://www.qsrinternational.com (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Rosen, P.M.; Heard, K.V. A Method for Reporting Self-Harm According to Level of Injury and Location on the Body. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 1995, 25, 381–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asarnow, J.R.; Goldston, D.B.; Tunno, A.M.; Inscoe, A.B.; Pynoos, R. Suicide, Self-Harm, & Traumatic Stress Exposure: A Trauma-Informed Approach to the Evaluation and Management of Suicide Risk. Evid. -Based Pract. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2020, 5, 483–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikopaschos, F.; Burrell, G.; Clark, J.; Salgueiro, A. Trauma-informed care on mental health wards: The impact of Power Threat Meaning Framework team formulation and psychological stabilisation on self-harm and restrictive interventions. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1145100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowe, R.; Townsend, M.L.; Miller, C.E.; Grenyer, B.F.S. Incidence, Severity and Responses to Reportable Student Self-Harm and Suicidal Behaviours in Schools: A One-Year Population-Based Study. Sch. Ment. Health 2020, 12, 841–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cully, G.; Corcoran, P.; Leahy, D.; Griffin, E.; Dillon, C.; Cassidy, C.; Shiely, F.; Arensman, E. Method of Self-Harm and Risk of Self-Harm Repetition: Findings from a National Self-Harm Registry. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 246, 843–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerr, P.L.; Muehlenkamp, J.J.; Turner, J.M. Nonsuicidal Self-Injury: A Review of Current Research for Family Medicine and Primary Care Physicians. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2010, 23, 240–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewson, T.; Gutridge, K.; Bernard, Z.; Kay, K.; Robinson, L. A Systematic Review and Mixed-Methods Synthesis of the Experiences, Perceptions and Attitudes of Prison Staff Regarding Adult Prisoners Who Self-Harm. BJPsych Open 2022, 8, E102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A.R.; Powis, J.; Carradice, A. Community Psychiatric Nurses’ Experience of Working with People Who Engage in Deliberate Self-Harm. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2008, 17, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morison, L.; Trigeorgis, C.; John, M. Are Mental Health Services Inherently Feminised? Psychologist 2014, 27, 414–416. Available online: https://www.bps.org.uk/psychologist/are-mental-health-services-inherently-feminised (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Babič, M.P.; Bregar, B.; Radobuljac, M.D. The Attitudes and Feelings of Mental Health Nurses towards Adolescents and Young Adults with Nonsuicidal Self-Injuring Behaviors. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2020, 14, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.; Ritchie, J.; McNaughton Nicholls, C.; Ormston, R. Generalizing from Qualitative Research. In Qualitative Research Practice, 2nd ed.; Ritchie, J., Lewis, J., McNaughton Nicholls, C., Ormston, R., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2014; pp. 347–366. [Google Scholar]

- Storm Skills Training. (n.d.). Self-Harm and Suicide Prevention Training. Available online: https://stormskillstraining.com/ (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- Appleby, L.; Morriss, R.; Gask, L.; Roland, M.; Lewis, B.; Perry, A.; Battersby, L.; Colbert, N.; Green, G.; Amos, T.; et al. An educational intervention for front-line health professionals in the assessment and management of sui-cidal patients (The STORM project). Psychol. Med. 2000, 30, 805–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gask, L.; Dixon, C.; Morriss, R.; Appleby, L.; Green, G. Evaluating STORM skills training for managing people at risk of suicide. J. Adv. Nurs. 2006, 54, 739–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, J.M.A.; Gray, A.; Rivero-Arias, O.; Saunders, K.E.A.; Hawton, K. Healthcare and Social Services Resource Use and Costs of Self-Harm Patients. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2011, 46, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsiachristas, A.; Geulayov, G.; Casey, D.; Ness, J.; Waters, K.; Clements, C.; Kapur, N.; McDaid, D.; Brand, F.; Hawton, K. Incidence and General Hospital Costs of Self-Harm across England: Estimates Based on the Multicentre Study of Self-Harm. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2020, 29, e108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, S.P.; Hasking, P.A. Self-Injury Recovery: A Person-Centered Framework. J. Clin. Psychol. 2021, 77, 884–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd-Richardson, E.E.; Hasking, P.; Lewis, S.; Hamza, C.; McAllister, M.; Baetens, I.; Muehlenkamp, J. Addressing Self-Injury in Schools, Part 1: Understanding Nonsuicidal Self-Injury and the Importance of Respectful Curiosity in Supporting Youth Who Engage in Self-Injury. NASN Sch. Nurse 2019, 35, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, B. Clinical Assessment of Self-Injury: A Practical Guide. J. Clin. Psychol. 2007, 63, 1057–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodley, S.; Hodge, S.; Jones, K.; Holding, A. How Individuals Who Self-Harm Manage Their Own Risk—‘I Cope Because I Self-Harm, and I Can Cope with my Self-Harm’. Psychol. Rep. 2021, 124, 1998–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, G. Learning by Doing: A Guide to Teaching and Learning Methods; Further Education Unit, Oxford Brookes University: Oxford, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

| Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 15 | 79 |

| Male | 4 | 21 |

| Age | ||

| 20–29 | 8 | 42 |

| 30–39 | 5 | 26 |

| 40–49 | 4 | 21 |

| 50–59 | 2 | 11 |

| Qualification | ||

| BTEC Diploma | 1 | 5 |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 2 | 11 |

| Master’s Degree | 12 | 63 |

| PHD | 1 | 5 |

| Missing | 3 | 16 |

| Job Role | ||

| Support Worker | 4 | 21 |

| Recovery Worker | 1 | 5 |

| Mental Health Support Worker | 3 | 16 |

| Nurse | 1 | 5 |

| Mental Health Nurse | 1 | 5 |

| Trainee Counselling Psychologist | 1 | 5 |

| Trainee Forensic Psychologist | 5 | 27 |

| Psychologist | 1 | 5 |

| Consultant Forensic Psychologist | 2 | 11 |

| Years of Clinical Experience | ||

| <1 | 1 | 5 |

| 1–2 | 2 | 10 |

| 3–4 | 4 | 21 |

| 5–6 | 2 | 11 |

| 7–8 | 3 | 16 |

| 9–10 | 2 | 11 |

| >10 | 5 | 26 |

| Self-Harm Training Undertaken | ||

| Yes | 11 | 58 |

| No | 8 | 42 |

| Themes |

|---|

|

| Word | Length | Count | Weighted Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| think | 5 | 808 | 3.88 |

| self-harm | 8 | 552 | 3.17 |

| distress | 8 | 443 | 1.98 |

| location | 8 | 421 | 1.97 |

| just | 4 | 363 | 1.83 |

| really | 6 | 339 | 1.63 |

| people | 6 | 274 | 1.58 |

| see | 3 | 467 | 1.46 |

| risk | 4 | 267 | 1.44 |

| individual | 10 | 309 | 1.40 |

| sort | 4 | 314 | 1.39 |

| function | 8 | 398 | 1.34 |

| level | 5 | 294 | 1.34 |

| body | 4 | 234 | 1.32 |

| know | 4 | 310 | 1.13 |

| get | 3 | 493 | 1.12 |

| areas | 5 | 192 | 1.10 |

| visible | 7 | 190 | 1.09 |

| injury | 6 | 253 | 1.08 |

| cut | 3 | 197 | 1.05 |

| lot | 3 | 240 | 1.02 |

| concealed | 9 | 218 | 1.01 |

| well | 4 | 180 | 0.97 |

| might | 5 | 167 | 0.96 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gardner, K.J.; Smith, R.; Rayner, G.; Lamph, G.; Moores, L.; Crossan, R.; Bisland, L.; Danino, N.; Taylor, P. Locating Meaning: Health Professionals’ Views on the Psychological and Clinical Significance of Self-Injury Sites. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 979. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22070979

Gardner KJ, Smith R, Rayner G, Lamph G, Moores L, Crossan R, Bisland L, Danino N, Taylor P. Locating Meaning: Health Professionals’ Views on the Psychological and Clinical Significance of Self-Injury Sites. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(7):979. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22070979

Chicago/Turabian StyleGardner, Kathryn Jane, Rachel Smith, Gillian Rayner, Gary Lamph, Lucie Moores, Robyn Crossan, Laura Bisland, Nicky Danino, and Peter Taylor. 2025. "Locating Meaning: Health Professionals’ Views on the Psychological and Clinical Significance of Self-Injury Sites" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 7: 979. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22070979

APA StyleGardner, K. J., Smith, R., Rayner, G., Lamph, G., Moores, L., Crossan, R., Bisland, L., Danino, N., & Taylor, P. (2025). Locating Meaning: Health Professionals’ Views on the Psychological and Clinical Significance of Self-Injury Sites. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(7), 979. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22070979