Instructors’ Views on and Experiences with Last Aid Courses as a Means for Public Palliative Care Education—A Longitudinal Mixed-Methods Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Framework of This Study

- Resource orientation: The principle of resource orientation emphasises that within a social space, the challenges, strengths and resources of the individuals and communities concerned should be considered.

- Participation: Participation is a central element of social space orientation. It is postulated that people in the social space should be actively involved in shaping their living conditions.

- Networking: The networking of the actors within a social space is of great importance for the success of social space-orientated approaches. Network actors, be they social institutions, neighbours or initiatives, can work together to develop solutions and use resources more efficiently.

- Sustainability: Sustainability in social space-orientated work implies that measures do not merely offer short-term solutions, but aim for long-term changes. This requires continuous reflection and adaptation of strategies and services in order to promote the residents’ ability to help themselves.

- Contextuality: The principle of contextuality states that social space-orientated measures must be adapted to the specific circumstances of a space.

2.2. Study Design, Data Collection and Analysis

- What are your experiences with Last Aid Courses?

- In which setting and location have the Last Aid Courses been held?

- What kind of practical exercises did you use in the Last Aid Course?

- May the Last Aid Courses serve to recruit people to become hospice volunteers?

- How can Last Aid Courses contribute to compassionate communities?

2.3. Setting, Participants and Sample Selection

- Certified German-speaking LAC instructor or LAC trainer;

- Participation in at least one German Last Aid symposium or Last Aid Trainer meeting.

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Data from the Questionnaires

3.2. Qualitative Data from the Questionnaires

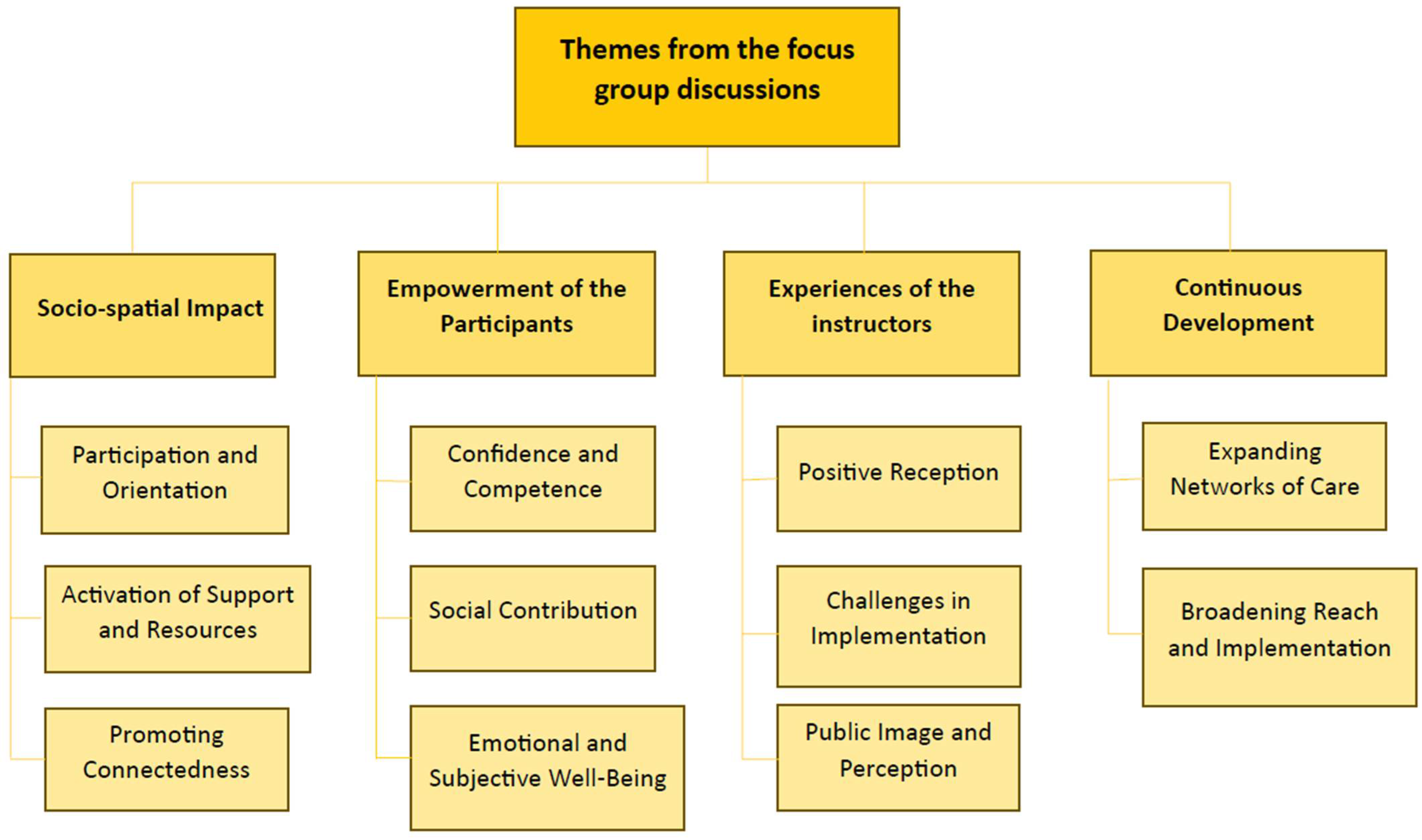

3.3. Qualitative Results from the Focus Group Interviews

- (1)

- Socio-Spatial Impact

- Participation and Orientation

‘And how do we strengthen our cohesion there again. It’s a great help, not just to go into the specialist area and say, ‘Here and there you get someone, but to encourage the citizens to be there for each other’.’(Trainer interview, p. 14)

‘People who are currently in the care situation or want to look retrospectively, did I do it right back then with my mum. Yes, it’s just great that we reach so many people with it and that people give consistently positive feedback.’(Trainer interview, p. 1)

- Activation of Support and Resources

‘…the aim is to encourage people to simply continue to live their lives, their families or whatever relationship systems they may have, as before.’(Group discussion Kassel 2, p. 13)

‘I think you can say that the networks expand through last aid courses because you build up contacts that you wouldn’t otherwise build up in this way, and last aid courses are also a good vehicle for getting into dialogue with each other.’(Trainer interview, p. 8)

‘… by empowering the people who attend our courses and encouraging them, bring yourselves with your talent, with your strengths, so look in the neighbourhood, in the neighbourhood.’(Trainer interview, p. 15)

- Promoting Connectedness

‘We also introduced our regional structures to people who needed more information and initiated contacts if there was a need for them.’(Group discussion Kassel 1, p. 10)

‘I can think of the church communities and organisations that say it’s important that we do a course like this so that we can get to grips with the topic, deal with it personally, because it might affect someone somewhere in our society at some point. And how do we strengthen our cohesion again?’(Trainer interview p. 14)

‘I run a course at the AWO /Arbeiterwohlfahrt) service centre for the staff there, who in turn use the neighbourhood helpers. And that’s where a network proves its worth…’(Trainer interview, p. 6)

- (2)

- Empowerment of the Participants

- Confidence and Competence

‘I also experience that fear of contact with the dying is reduced, i.e., the idea that you are not allowed to sit in bed with them, and you are not allowed to hold them from behind if they have difficulty breathing, and you are also allowed to lie in bed with the dying person.’(Group discussion Kassel 2, p. 11)

‘So the best feedback for me was actually from two women who said afterwards that this four-hour course had given them such a sense of security in accompanying a dying person that they felt well prepared, always ready for the next symptom that comes and had a total calmness in the accompaniment, or how you can achieve that with four hours, it’s great.’(Group discussion Kassel 2, p. 4)

- Social Contribution

‘And how do we strengthen our cohesion there too. It’s a great help, not just that it goes into the technical side of things, but that you bring someone in and encourage people to be there for each other.’(Trainer interview, p. 14)

- Emotional and Subjective Well-Being

‘… and then there are also personal experiences that come up in the course, and I think that’s very important, not just the course content, but that we meet people in person, that there is space and time for them to report and that we incorporate this and learn from each other together.’(Trainer interview, p. 1)

- (3)

- Experiences of the Instructors

- Positive Reception

‘At our Hospice Academy, last-aid courses are more or less like hot cakes, they are always fully booked. Both in our programme and as in-house training courses, we only have good experiences with good feedback.’(Trainer interview, p. 1)

‘… they sort of soak it up like a sponge and are really, really interested.’(Trainer interview p.4)

‘So for me that shows that it’s getting a very high level of penetration more and more in the sense of awareness, of ‘this is worthwhile’. And it’s no longer just our job to advertise, but to keep the ball rolling.’(Trainer interview, p. 8)

- Challenges in Implementation

‘We are completely overrun and always have a waiting list.’(Group discussion Kassel 2, p. 1)

‘Well, I’ve also had two mishaps in terms of registration, once at the parish in Mörlebach, where the deacon advertised it and then went on holiday for three weeks. And people registered at the parish office, and then I came to hold the course and there were 36 people there.’(Trainer interview, p. 8)

‘… and then you only find out about the pitfalls on site, which means that you still have to improvise some things.’(Group discussion Kassel 2, p. 4)

‘Sure we get donations, but if you think about it, that’s not enough to finance our working hours.’(Group discussion Kassel 1, p. 5)

- Public Image and Perception

‘They are interested in doing it, so the demand seems to be there among the trainees. (…) But there are reservations about clearly stating what it is.’(Trainer interview, p. 10)

‘(…)Last Aid is still seen as competition, not at all as a basic information event at a low-threshold level or, but always as competition to a longer Palliative Care Course and to other specialised training courses. (…) I think that is sometimes the case, perhaps a small image problem that we have as last aid.’(Trainer interview, p. 16)

- (4)

- Continuous Development

- Expanding Networks of Care

‘It also happens with us that one or two people who have made this career through an information evening perhaps and then attend a last aid course and then become volunteers.’(Trainer interview, p. 2)

- Broadening Reach and Implementation

‘Even people who needed more information, where we then also introduce our regional structures, initiate contacts…’(Group discussion Kassel 1, p. 10)

‘Or requests for accompaniment, we have that again and again. When the relatives are at home during the course, we come into contact with them and that sometimes leads to counselling.’(Group discussion Kassel 1, p. 10)

‘For example, we were approached by a yoga centre. These are completely different people who go to the course.’(Trainer interview, p. 7)

‘So we reach a lot of people there, and the best thing about the courses is that they are really colourful (…) people who are currently in a care situation or want to look back (…).’(Trainer interview, p. 1)

‘We developed the last aid course for professional careers, which runs over eight hours. Then, we tested it in a facility, so we trained the whole building, the day-to-day carers with the Müller course and the nursing staff with our newly developed course (…).’(Group discussion Kassel 2, p. 7)

4. Discussion

Practice Implications and Future Research Directions

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LAC | Last Aid Course |

| LARGI | Last Aid Research Group International |

| OLAC | Online Last Aid Course |

| PHPC | Public Health Palliative Care |

| PPCE | Public Palliative Care Education |

References

- Bollig, G. Palliative Care für Alte und Demente Menschen Lernen und Lehren; LIT: Berlin, Germany, 2010; pp. 61–68. [Google Scholar]

- Deutscher Bussgeldkatalog. Erste Hilfe: In Medizinischen Notfällen Ist Sie Unerlässlich. Available online: https://www.bussgeldkataloge.de/erste-hilfe/ (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Sternswärd, J.; Foley, K.M.; Ferris, F.D. The Public Health Strategy for Palliative Care. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2007, 33, 486–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, S.; Truner, N.; Fryer, K.; Beng, J.; Ogden, M.E.; Watson, M.; Gardiner, C.; Bayly, J.; Sleeman, K.E.; Evans, C.J. A framework for more equitable, diverse, and inclusive Patient and Public Involvement for palliative care research. Res. Involv. Engagem. 2024, 10, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kellehear, A. Compassionate communities: End-of-life care as everyone’s responsibility. QJM 2013, 106, 1071–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kellehear, A. Compassionate Cities. Public Health and End-of-Life Care; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2005; pp. 117–136. [Google Scholar]

- Etkind, S.N.; Bone, A.E.; Gomes, B.; Lovell, N.; Evans, C.J.; Higginson, I.J.; Murtagh, F.E.M. How many people will need palliative care in 2040? Past trends, future projections and implications for services. BMC Med. 2017, 15, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bollig, G.; Brandt, F.; Ciurlionis, M.; Knopf, B. Last Aid Course. An education for all citizens and an ingredient of compassionate communities. Healthcare 2019, 7, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Dirscheid, B.; Krause, M.; Lehmann, T.; Stichling, K.; Jansky, M.; Nauck, F.; Wedding, U.; Schneider, S.; Marschall, U.; Meißner, W.; et al. Palliativversorgung am Lebensende in Deutschland–Inanspruchnahme und regionale Verteilung. Bundesgesundheitsblatt 2020, 63, 1502–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dasch, B.; Zahn, P.K. Place of death trends and utilization of outpatient palliative care at the end of life–analysis of death certificates (2001, 2011, 2017) and pseudonymized data from selected palliative medicine consultation services (2017) in Westphalia, Germany. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2021, 118, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Last Aid International. Available online: https://www.letztehilfe.info/last-aid/ (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Mueller, E.; Bollig, G.; Becker, G.; Boehlke, C. Lessons learned from introducing Last Aid Courses at a University Hospital in Germany. Healthcare 2021, 9, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, J.; Rosenberg, J.P.; Bollig, G.; Haberecht, J. Last Aid and Public Health Palliative Care: Towards the development of personal skills and strengthened community action. Prog. Palliat. Care 2020, 28, 343–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollig, G.; Meyer, S.; Knopf, B.; Schmidt, S.; Bauer, E.H. First Experiences with Online Last Aid Courses for Public Palliative Care Education during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Healthcare 2021, 9, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bollig, G.; Gräf, K.; Gruna, H.; Drexler, D.; Pothmann, R. “We Want to Talk about Death, Dying and Grief and to Learn about End-of-Life Care”—Lessons Learned from a Multi-Center Mixed-Methods Study on Last Aid Courses for Kids and Teens. Children 2024, 11, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zelko, E.; Bollig, G. Report from the Third International Last Aid Conference: Cultural diversity in palliative care. Palliat. Care Soc. Pract. 2023, 17, 26323524231166932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bollig, G.; Hayes Bauer, E. Last Aid Courses as measure for public palliative care education—A narrative review. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2021, 10, 8242–8253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 4th international Last Aid Conference Cologne. Available online: https://www.letztehilfe.info/last-aid-conference-2024/ (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Bollig, G.; Kristensen, F.B.; Wolff, D.L. Citizens appreciate talking about death and learning end-of-life care—A mixed-methods study on views and experiences of 5469 Last aid Course participants. Prog. Palliat. Care 2021, 293, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fürst, R.; Hinte, W. Sozialraumorientierung 4.0. Das Fachkonzept: Prinzipien, Prozesse & Perspektiven; Facultas: Wien, Austria, 2020; pp. 11–49. [Google Scholar]

- Grunwald, K.; Thiersch, H. Praxishandbuch Lebensweltorientierte Soziale Arbeit. Handlungszusammenhänge und Methoden in Unterschiedlichen Arbeitsfeldern. 3. Aufl.; Beltz Juventa: Weinheim, Germany; Basel, Switzerland, 2016; p. 24. [Google Scholar]

- Löw, M. Raumsoziologie; Suhrkamp: Frankfurt, Germany, 2001; pp. 224–273. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. Sozialer Raum Und “Klassen”; Suhrkamp Verlag: Frankfurt, Germany, 1985; pp. 9–42. [Google Scholar]

- O’Cathain, A.; Murphy, E.; Nicholl, J. The Quality of Mixed Methods Studies in Health Services Research. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2008, 13, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malterud, K. Kvalitative Metoder i Medisinsk Forskning; Universitetsforlaget: Oslo, Norway, 2011; pp. 15–222. [Google Scholar]

- Kvale, S. Interviews–An Introduction to Qualitative Research Interviewing, 1st ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1996; pp. 124–209. [Google Scholar]

- Amberscript. Available online: https://www.amberscript.com/en/ (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Thorne, S.; Kirkham, S.R.; MacDonald-Emes, J. Interpretive description: A noncategorical qualitative alternativefor developing nursing knowledge. Res. Nurs. Health 1997, 20, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorne, S.E. Interpretive Description: Qualitative Research for Applied Practice, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 23–36. [Google Scholar]

- Thorne, S.; Kirkham, S.R.; O’Flynn-Magee, K. The analytic challenge in interpretive description. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2004, 3, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejdahl, C.T.; Schougaard, L.M.V.; Hjollund, N.H.; Riskjær, E.; Thorne, S.; Lomborg, K. PRO-based follow-up as a means of self-management support—An interpretive description of the patient perspective. J. Patient-Rep. Outcomes 2018, 2, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EQUATOR Network. Available online: https://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/coreq/ (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- de Lima, L.; Pastrana, T. Opportunities for Palliative Care in Public Health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2016, 37, 357–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Cross, S.H.; Kavalieratos, D. Public Health and Palliative Care. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2023, 39, 95–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peeler, A.; Doran, A.; Winter-Dean, L.; Ijaz, M.; Brittain, M.; Hansford, L.; Wyatt, K.; Sallnow, L.; Harding, R. Public health palliative care interventions that enable communities to support people who are dying and their carers: A scoping review of studies that assess person-centered outcomes. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1180571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abel, J.; Kellehear, A. Public health palliative care: Reframing death, dying, loss and caregiving. Palliat. Med. 2022, 36, 768–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahid, A.S.; Sayma, M.; Jamshaid, S.; Kerwat, D.; Oyewole, F.; Saleh, D.; Ahmed, A.; Cox, B.; Perry, C.; Payne, S. Barriers and facilitators influencing death at home: A meta-ethnography. Palliat. Med. 2018, 32, 314–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McIlfatrick, S.; Hasson, F.; McLaughlin, D.; Johnston, G.; Roulston, A.; Rutherford, L.; Noble, H.; Kelly, S.; Craig, A.; Kernohan, G. Public awareness and attitudes toward palliative care in Northern Ireland. BMC Palliat. Care 2013, 12 (Suppl. S1), 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gopal, K.S.; Archana, P.S. Awareness, knowledge and attitude about palliative care, in general, population and health care professionals in tertiary care hospital. Int. J. Sci. Study 2016, 3 (Suppl. S10), 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- McIlfatrick, S.; Slater, P.; Beck, E.; Bamidele, O.; McCloskey, S.; Carr, K.; Muldrew, D.; Hanna-Trainor, L.; Hasson, F. Examining public knowledge, attitudes and perceptions towards palliative care: A mixed method sequential study. BMC Palliat. Care 2021, 20, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giehl, C.; Chikradze, N.; Bollig, G.; Vollmer, H.C.; Otte, I. “I Needed to Know, No Matter What I Do, I Won’t Make It Worse”—Expectations and Experiences of Last Aid Course Participants in Germany—A Qualitative Pilot Study. Healthcare 2023, 11, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biondo, P.; Shantz, M.A.; Zheng, Y.B.; Manning, M.; Kashuba, L. Developing the Understanding Palliative Care Module: A Quality Improvement Initiative Incorporating Public, Patient, and Family Caregiver Perspectives. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fliedner, M.C.; Zambrano, S.C.; Eychmueller, S. Public perception of palliative care: A survey of the general population. Palliat. Care Soc. Pract. 2021, 15, 26323524211017546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, M. Handbuch Sozialraumorientierung; Kohlhammer: Stuttgart, Germany, 2020; pp. 244–267. [Google Scholar]

- Bleck, C.; van Rießen, A.; Knopp, R. Altern und Pflege im Sozialraum; Springer: Wiebaden, Germany, 2018; pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Rüßler, H.; Stiel, J. Im Quartier Selbstbestimmt Älter Werden: Partizipation, Lebensqualität und Sozialraumbezug. Sozialraum.de(5) Ausgabe 1/2013. Available online: http://www.sozialraum.de/im-quartier-selbstbestimmt-aelter-werden.php (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Teixeira, M.J.C.; Alvarelhão, J.; de Souza, D.N.; Teixeira, H.J.C.; Abreu, W.; Costa, N.; Machado, F.A.B. Healthcare professionals and volunteers education in palliative care to promote the best practice–an integrative review. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2019, 33, 311–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanderstichelen, S.; Cohen, J.; Van Wesemael, Y.; Deliens, L.; Chambaere, K. The liminal space palliative care volunteers occupy and their roles within it: A qualitative study. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2020, 10, e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letzte Hilfe. Available online: https://www.letztehilfe.info (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Sallnow, L.; Smith, R.; Ahmedzai, S.H.; Bhadelia, A.; Chamberlain, C.; Cong, Y.; Doble, B.; Dullie, L.; Durie, R.; Finkelstein, E.A.; et al. Report of the Lancet Commission on the Value of Death: Bringing death back into life. Lancet 2022, 399, 837–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Meeting | 2. German Last Aid Symposium in Kassel in 2018 | 3. German Last Aid Symposium in Munich in 2019 | Last Aid Trainer Meeting in Schleswig in 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of participants | 77 | 118 | 9 |

| Number of returned questionnaires | 37 | 72 | 9 |

| Return rate | 48% | 61% | 100% |

| Age (range and mean) | n.o. | 40–78 (57) | 42–67 (50) |

| Female | n.o. | 60 | 5 |

| Male | n.o. | 11 | 4 |

| Other | n.o. | 0 | 0 |

| No information about gender in questionnaire | n.o. | 1 | 0 |

| Number of Last Aid Courses Taught (range and mean) | 0–20 (5.8) | 0–20 (5.3) | 3–60 (27) |

| Theme | Subtheme | Quotations from the Questionnaires |

|---|---|---|

| Informal Peer Advice | Organisational Aspects and Environment | “‘In the midst of life’—football stadium, communities, museum; everywhere hospice/ambulatory hospice service.” “If it is prepared with ‘love,’ the location doesn’t matter.” |

| Engagement and Interaction | “Very moving personal disclosures with grief reactions. Every time, at the end, realizing that the participants feel touched.” | |

| Variety in Teaching Methods | “Reporting case studies and personal experiences, having an emergency kit for the fridge, and engaging in practical skills such as hand massage, touch, and oral care are all important components. The presentation of films and books, alongside the use of varied methods, helps prevent fatigue and keeps participants engaged.” | |

| Impact | Instructors’ Experiences | “The gratitude of a participant who, after the course, felt confident enough to let her husband die at home.” “Human support! For example, a lady had a bad feeling because her mother no longer allowed herself to be touched in her final hours. Once she learned that this was normal and why, she felt relieved.” |

| Community and Recruitment | “Recruiting volunteer helpers/hospice volunteers. Participants feel encouraged and empowered to accompany the dying in the future, contributing to helping people lose their fear of dying and engage with the topic.” “Regional connections and available offerings.” | |

| Participants Empowerment | “The sudden realisation of a participant: If I do everything the same way as with my baby, then it’s actually right—and I already know how to do it!” “A participant’s statement after the course: Now I am much less afraid.” “A mother and daughter, who cared for and accompanied their husband/father with glioblastoma, left the course feeling very empowered without dominating the course.” | |

| Time Management | “A limited timeframe restricts the variety of methods.” “Point out the time limit from the beginning. Offer alternatives and advice for later.” | |

| Technical | “Rooms with good technical equipment and no long, narrow spaces.” | |

| Challenges | Participant-Related | “Different participants with varying levels of knowledge. Participants who dive into their personal struggles and take up a lot of space.” “Uncertain group dynamics.” |

| Facilitation and Coordination | “Collaboration with a co-leader who struggles to be concise.” “Catering to the needs of all participants.” | |

| Applying Practical Skills | “Oral care with different materials and flavours. Everyone is allowed to try oral care (possibly with a neighbour).” “Kinesthetic positioning, and gentle stroking from the ear downwards to stimulate saliva production.” | |

| Alternative Teaching Methods | “Drawing cards on the topic of grief and reading them aloud.” “Breathing through a straw (as a simulation of breathlessness).” | |

| Symptom awareness | Diversity of symptoms | “Address the specificities of dying in people with dementia.” “Assign symptoms to the dimensions of Total Pain.” |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bollig, G.; Müller-Koch, S.; Zelko, E. Instructors’ Views on and Experiences with Last Aid Courses as a Means for Public Palliative Care Education—A Longitudinal Mixed-Methods Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1117. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22071117

Bollig G, Müller-Koch S, Zelko E. Instructors’ Views on and Experiences with Last Aid Courses as a Means for Public Palliative Care Education—A Longitudinal Mixed-Methods Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(7):1117. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22071117

Chicago/Turabian StyleBollig, Georg, Sindy Müller-Koch, and Erika Zelko. 2025. "Instructors’ Views on and Experiences with Last Aid Courses as a Means for Public Palliative Care Education—A Longitudinal Mixed-Methods Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 7: 1117. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22071117

APA StyleBollig, G., Müller-Koch, S., & Zelko, E. (2025). Instructors’ Views on and Experiences with Last Aid Courses as a Means for Public Palliative Care Education—A Longitudinal Mixed-Methods Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(7), 1117. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22071117